Summary

This study aimed to propose an alternative treatment for carotid cavernous fistula (CCF) using the balloon-assisted sinus coiling (BASC) technique and to describe this procedure in detail.

Under general anesthesia, we performed the BASC procedure to treat five patients with traumatic CCF. Percutaneous access was obtained via the right femoral artery, and a 7F sheath was inserted, or alternatively, a bifemoral 6F approach was accomplished. A microcatheter was inserted into the cavernous sinus over a 0.014-inch microwire through the fistulous point; the microcatheter was placed distal from the fistula point, and a “U-turn” maneuver was performed. Through the same carotid access, a compliant balloon was advanced to cross the point of the fistula and cover the whole carotid tear. Large coils were inserted using the microcatheter in the cavernous sinus. Coils filled the adjacent cavernous sinus, respecting the balloon.

Immediate complete angiographic resolution was achieved, and an early angiographic control (mean = 2.6 months) indicated complete stability without recanalization. The clinical follow-up has been uneventful without any recurrence (mean = 15.2 months).

An endovascular approach is optimal for direct CCF. Because the detachable balloon has been withdrawn from the market, covered stenting requires antiplatelet therapy and its patency is unconfirmed, but cavernous sinus coiling remains an excellent treatment option. Currently, there is no detailed description of the BASC procedure. We provide detailed angiograms with suitable descriptions of the exact fistula point, and venous drainage pathways. Familiarity with these devices makes this technique effective, easy and safe.

Keywords: trauma, carotid artery, cavernous sinus fistula, endovascular treatment, embolization

Introduction

Carotid cavernous fistulas (CCF) are abnormal arteriovenous communications between the carotid artery or its branches and the cavernous sinus (CS). The most commonly used classification scheme, established by Barrow et al. 1, classifies CCFs into four types: Type A fistulas are direct, high-flow shunts between the internal carotid artery (ICA) and the CS, which usually occur after trauma or the rupture of a carotid cavernous aneurysm; Type B are dural shunts between meningeal branches of the ICA and the CS; Type C are dural shunts between meningeal branches of the external carotid artery (ECA) and the CS; and Type D are dural shunts between meningeal branches of both the ICA and ECA and the CS.

While various treatment methods have been used, endovascular therapy has emerged as the safest and most effective way to treat CCF 2. The goal in treating a direct CCF (Type A) is to occlude the fistula site and, if possible, preserve the patency of the ICA 3.

Methods

We retrospectively collected data and analyzed five consecutive cases (Table 1) of direct traumatic CCF managed in our institution and treated with transarterial sinus coiling embolization using the balloon remodeling technique. The characteristics of the fistula, the route of embolization, the number of coils, procedural complications, and clinical and angiographic follow-up were recorded. We describe this new approach in detail.

Table 1.

Summary of patient demographics, procedural technique, follow-up and cortical drainage

| Patient | Gender | Age | No Coils | Angio FU | Clinical FU | Cortical Drainage |

| 1 | M | 15y | 12 | 3 months | 32 months | N |

| 2 | M | 37y | 8 | 3 months | 15 months | P |

| 3 | F | 43y | 18 | 2 months | 3 months | N |

| 4 | F | 43y | 6 | 2 months | 19 months | P |

| 5 | M | 66y | 12 | 3 months | 7 months | N |

| Total | 3M, 2F | 40.8y | 11.2 | 2.6 months | 15.2 months | 40% P |

| M = Male, F = Female, y = years, No = Number, FU = Follow-up, N = Negative, P = Positive | ||||||

Technical Note

Over the last twelve years, we treated 48 patients with direct CCF using different devices: detachable balloons were used in 30, a covered stent was used in two, coils were used in eight and multiple devices were used in eight patients. Due to problems with detachable balloons, technical difficulties with the balloons and their lack of commercial availability in Brazil since 2009, we treated the last five patients using balloon-assisted sinus coiling (BASC) which is now our preferred approach. Balloon test occlusion was performed in all patients, but none of them tolerated the test. Under general anesthesia with assisted ventilation, electrocardiogram, arterial oxygen saturation and blood pressure monitoring, a percutaneous access was obtained via the right femoral artery, and a 7F sheath was inserted; alternatively, a bifemoral 6F approach was taken. A bolus injection of heparin (5,000 IU) was administered before placement of the guide catheter into the internal carotid, and an additional 1,000-IU bolus of heparin was administered every hour. A 7F guiding catheter (Mach1, Boston Scientific) was positioned in the distal cervical ICA, and preprocedural angiograms were obtained in orthogonal planes. If necessary, rotational acquisitions were obtained to confirm the diagnosis of CCF and to identify the exact point of the fistula. A microcatheter was inserted into the cavernous sinus over a 0.014-inch microwire through the fistulous point. The initial position of this coiling microcatheter is of prime importance. We tried to place it as distal from the fistula point as possible and performed a “U-turn” maneuver (Figure 1A) with its tip to avoid pulling back parts of the carotid. We prefer to leave the microcatheter tip facing the carotid artery such that when the coils are pushed, the microcatheter is not removed prematurely from the cavernous sinus (as might occur when it is facing the cavernous sinus). Through the same carotid, we advanced a compliant balloon that crossed the point of the fistula (Hyperglide Balloon, 4 × 20 mm, ev3) and covered the whole carotid tear (Figure 1A). When everything was positioned, the balloon was filled, and using the microcatheter located in the cavernous sinus, large coils were placed one by one while observing the movements of the cast after deflation of the balloon. We prefer 0.018‘ long coils over 20 cm. It is interesting to note how the coils fill the adjacent cavernous sinus, respecting the balloon (Figure 1B).

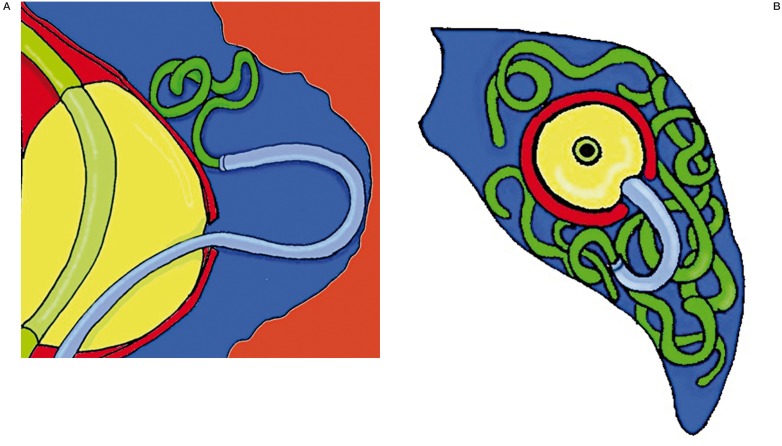

Figure 1.

A) The exact location of the fistula and a compliant balloon, which crosses the fistula and covers the whole carotid tear, and a microcatheter located in the cavernous sinus after a “U-turn” maneuver. B) The location where large coils should be placed, respecting the balloon.

Results

Illustrative Cases

Patient No 1

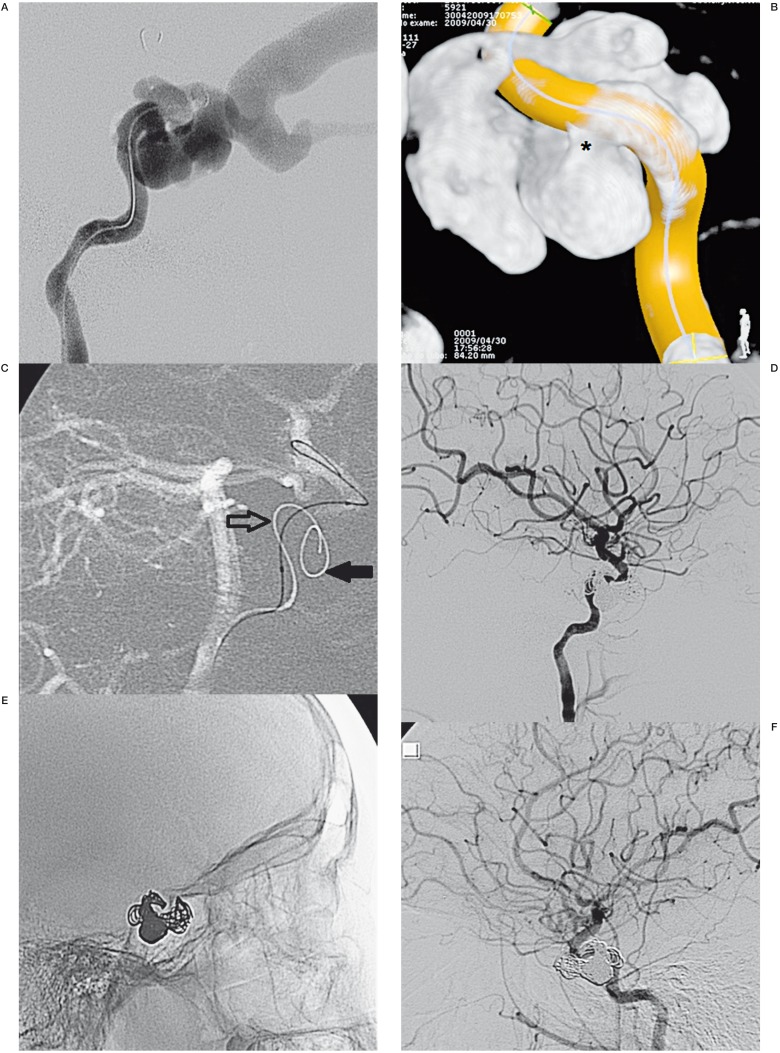

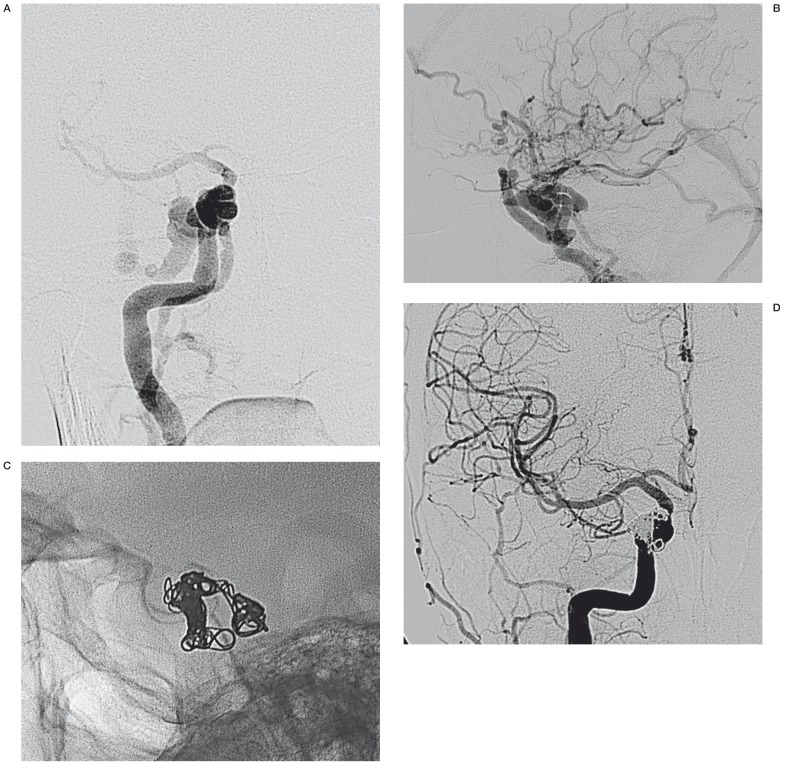

A 15-year-old boy presented with proptosis and chemosis two months after a traffic accident and was diagnosed with a left direct CCF with drainage of the ophthalmic veins (upper and lower) (Figure 2A). Through a bilateral 6F femoral approach, we performed a tridimensional acquisition identifying the exact fistula point (Figure 2B). An Echelon 14 microcatheter (ev3) was positioned inside the cavernous sinus with “U-turn” tip, and through the other guiding-catheter, a long compliant balloon (Hyperglide 4 × 20 mm) was crossed over the cavernous carotid tear (Figure 2C).

Finally, we performed the BASC procedure with eight long Axium detachable coils, achieving complete resolution of the CCF (Figure 2D,E). Control angiography after two months showed stability in that the fistula was healed and the carotid was preserved (Figure 2F). The patient showed amelioration from the ocular manifestations.

Figure 2.

A) Lateral view of a left ICA angiogram showing a high-flow CCF draining into the left superior and inferior ophthalmic vein. B) Rotational acquisition demonstrates the exact location of the fistula (asterisk). C) Lateral view of the left ICA angiogram reveals two microcatheters with the first being inserted into the cavernous sinus (filled arrow) and the balloon along the internal carotid (open arrow). D,E) Immediate angiograms confirmed a complete obliteration of the fistula with 12 coils. F) Three months after the angiogram, a complete resolution of the CCF was observed. ICA, internal carotid artery; CCF, carotid cavernous fistula.

Patient No 2

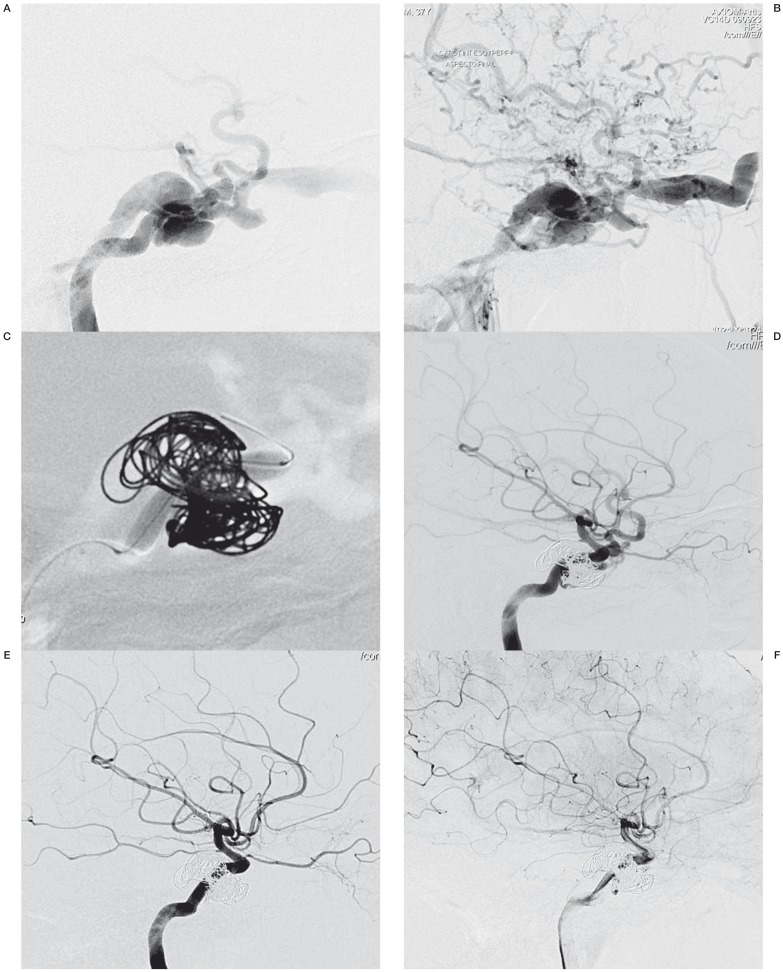

A 37-year-old man, a victim of a motorcycle accident without a helmet, developed left proptosis and chemosis three months post trauma. Digital angiography showed a direct carotid cavernous fistula with draining into the left superior and inferior ophthalmic vein and inferior petrosal sinus (Figure 3A) associated with intense cortical venous reflux (Figure 3B).

Under general anesthesia, we performed the BASC procedure through a 7F femoral approach. Using a 7F guiding catheter (Mach1, Boston Scientific), we microcatherized the sinus (Echelon 14, ev3) and crossed the tear with a Hyperglide balloon (Figure 3C). Immediate control angiography (Figure 3D) and control angiography performed one month later (Figure 3E,F) showed reduction of the cortical drainage and complete resolution of the CCF. Clinically, all symptoms were resolved.

Figure 3.

A) Lateral view of a left ICA angiogram showing a high-flow CCF draining into the left superior and inferior ophthalmic vein and inferior petrosal sinus. B) Lateral view of a left ICA angiogram showing intense cortical venous reflux. C) Angiographic view of compliant balloon (open arrow) and cast of coils. D) Immediate angiogram in lateral view demonstrated a complete resolution of the CCF. E,F) One month later, control angiograms revealed a reduction of the cortical drainage and a complete resolution of the CCF. ICA, internal carotid artery; CCF, carotid cavernous fistula.

Patient No 3

A 43-year-old woman, a victim of a motorcycle accident, developed left proptosis and chemosis post-trauma, associated with pulsatile tinnitus.

Three months later, a bilateral chemosis was noted, which was worse on the left side. At that time, the patient sought medical attention. Digital angiography showed a direct CCF with drainage into the left superior ophthalmic vein, the inferior petrosal sinus (Figure 4A), and the contralateral CS (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

A) Lateral view of a left ICA angiogram showing a high-flow CCF draining into the left superior ophthalmic vein and inferior petrosal sinus. B) Anterior-posterior view in the venous phase, showing CCF draining into the contralateral CS. C) Angiographic view of the compliant balloon and a cast of coils. D) Three months later, a control angiogram revealed a complete resolution of the CCF. ICA, internal carotid artery; CCF, carotid cavernous fistula; CS, cavernous sinus.

Under general anesthesia, we performed the BASC procedure (Figure 4C). An immediate control angiography and a three-month control angiography showed complete resolution of the CCF (Figure 4D).

Clinically, the patient's tinnitus was completely resolved, and ocular events were not observed.

Patient No 4

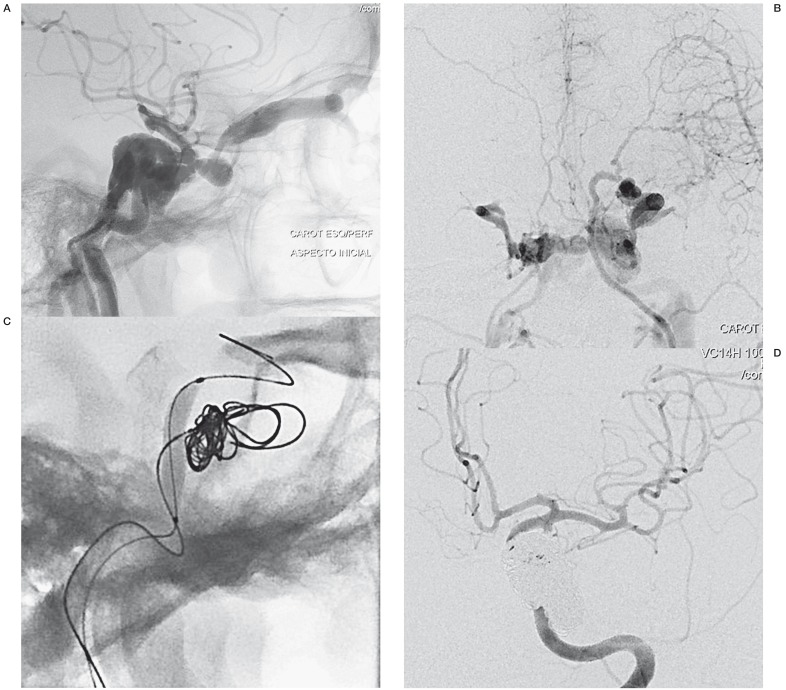

A 43-year-old woman presented with sudden headache and was diagnosed with a right direct CCF (Figure 5A) with intense cortical venous reflux (Figure 5B).

Under general anesthesia, we performed a 6F bi-femoral approach, which permits a carotid balloon test occlusion. Later, with both 6F guiding catheter in the same ICA, the BASC was performed using a microcatheter in the sinus (Echelon 14 - ev3) and crossed the tear with a Hyperglide balloon. It was necessary to use six long Axium detachable coils (Figure 5C) to complete resolution of the CCF (Figure 5D), and the patient recovered with no additional complication.

Figure 5.

A) Antero-posterior view of a right ICA angiogram showing a high-flow CCF, with intense cortical reflux at lateral angiography (B), and status post BASC procedure with a dense cast of coils (C). D) Two months later, a control angiogram revealed a complete resolution of the CCF with no cortical reflux. ICA, internal carotid artery; CCF, carotid cavernous fistula.

Patient No 5

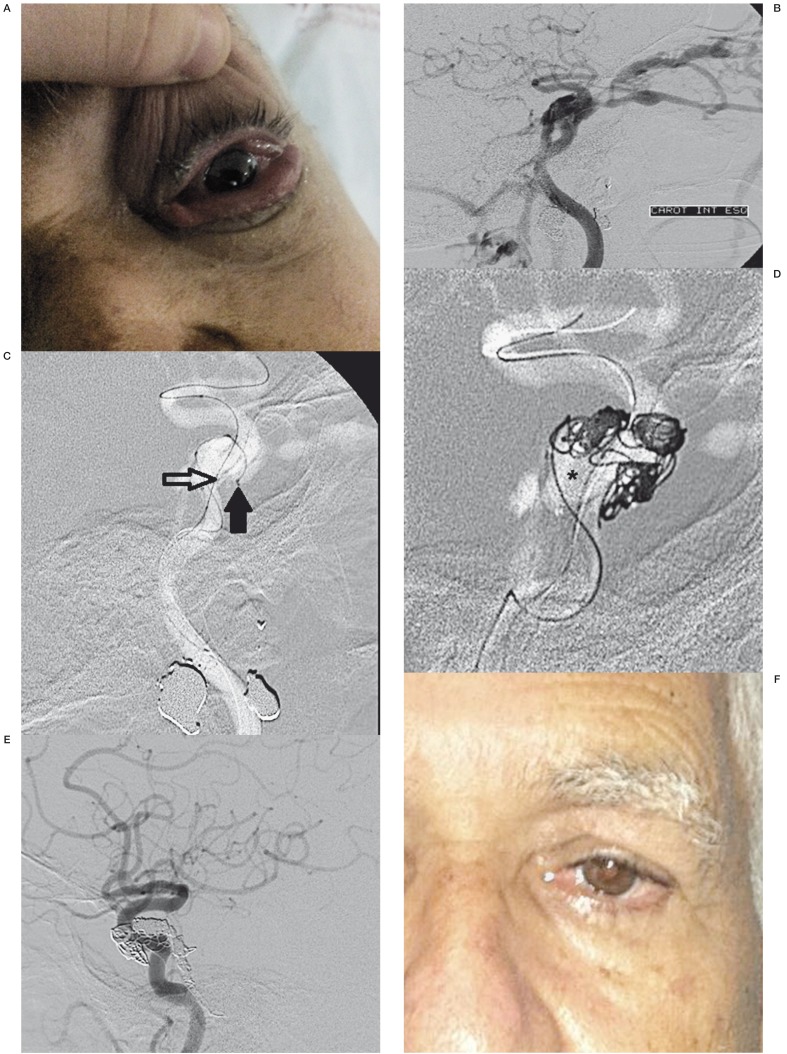

A 65-year-old man, a retired police officer, was approached by thieves who assaulted and shot him. He was admitted to the emergency room because of a firearm projectile in the region of the face and was discharged without complaints. Four months after the incident, the patient began to show left eye chemosis associated with paralysis of ipsilateral III, IV and VI cranial nerves (Figure 6A).

Digital angiography showed a direct carotid cavernous fistula with drainage to the left ophthalmic veins and inferior petrous sinus (Figure 6B).

One month later, under general anesthesia, we performed the BASC procedure via a 7F femoral approach. Using a 7F guiding catheter (Mach1, Boston Scientific) we microcatherized the sinus (Echelon 14, ev3) and crossed the tear with a Hyperglide balloon (Figure 6C,D). Immediate control angiography and angiography performed again after three months showed a complete regression of the fistula (Figure 6E), and the patient recovered uneventfully (Figure 6F).

Figure 6.

A) Clinical picture of a left eye chemosis associated with paralysis of the ipsilateral III, IV and VI cranial nerves. B) Lateral view of a left ICA angiogram showing a high-flow CCF draining into the left superior and inferior ophthalmic vein and inferior petrosal sinus. C) Lateral view of a left ICA angiogram showing two microcatheters with the first being inserted into the cavernous sinus (filled arrow) and a compliant balloon along the internal carotid (open arrow). D) Angiography lateral view of the inflated balloon (asterisk) and a partial cast of coils. E) Three months later, a control angiogram revealed a complete resolution of the CCF. F) The patient's clinical follow-up was uneventful. ICA, internal carotid artery; CCF, carotid cavernous fistula.

Discussion

Since the late seventies, the endovascular approach has been considered the optimal therapy for type A CCF, and a number of different endovascular treatment options are available, depending on the anatomy of the fistula and the preference of the operator or institution.

The most commonly used device worldwide is the detachable balloon, which was introduced by Serbinenko 4 and consists of placing the balloon within the ICA lesion 5. However, the balloon is not easy to use, and such problems as spontaneous detachment, deflation, perforation and recanalization have been described. In 2009, the detachable balloon was withdrawn from the market in Brazil. Transarterial embolization with coiling or other means of embolization have partly replaced detachable balloons.

The other frequently used technique is placing a microcatheter across the tear into the CS and subsequently filling the sinus with detachable coils 6 to occlude the direct communication. Nevertheless, any type of remodeling should employ a balloon or a stent; the use of coils alone should be avoided because they may cause occlusion or thromboembolism by herniation or leakage into the parent vessel 7.

We suggest remodeling with a balloon because it is inexpensive, no antiplatelet therapy is necessary and better sealing is achieved during the coiling. Choi et al. 8 attempted but failed to occlude a fistula because of a large linear tear and herniation of the coil in the parent artery. Several authors advocate stent utilization for carotid scaffolds. Covered stenting of the cavernous carotid seems to be the easiest and more logical treatment, but it is not. Stent availability, navigation and sealing are not optimal for tortuous and thin vessels. If the tearing has occurred in a straight segment, a covered stent is an excellent option. Another issue is antiplatelet therapy, as certain patients may experience a hemorrhagic complication 9 or cortical reflux. The patency of this method has not been established 8,10,11.

To date, there has been no detailed description available concerning the BASC technique for traumatic CSF. Several authors used similar techniques for other diseases, e.g., indirect CCF 12, cavernous aneurysm with direct CCF 13, or using other means of embolization for direct CCF, e.g., n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate 14 or ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer (Onyx, ev3) 12. We tried this technique in our last five patients and achieved excellent clinical and angiographic results in all of them. No complications or any adverse effects were observed. Immediate complete angiographic resolution was achieved, and an early control angiography (mean= 2.6 months) showed complete stability without any recanalization. The clinical follow-up continues to be uneventful without any recurrence (mean length of follow-up: 15.2 months). Table 2 shows the main advantages of using the BASC technique.

Table 2.

Main advantages of the BASC technique

| 1. | Widely available (unlike detachable balloons) |

| 2. | Avoids coil jumping into the parent vessel (unlike a coil used alone) |

| 3. | Cheaper, compared to other techniques; |

| 4. | No antiplatelet therapy necessary (unlike covered stents) |

| 5. | Can be used in patients with hemorrhagic complications |

We have provided detailed descriptions and angiograms with exact location of the fistula and venous drainage pathways, and we demonstrated that this technique is effective, easy and safe.

References

- 1.Barrow DL, Spector RH, Braun IF, et al. Classification and treatment of spontaneous carotid- cavernous sinus fistulas. J Neurosurg. 985;62:248–256. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.62.2.0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elhammady MS, Peterson EC, Aziz-Sultan MA. Onyx embolization of a carotid cavernous fistula via direct transorbital puncture. J Neurosurg. 2011;114(1):129–132. doi: 10.3171/2010.1.JNS091433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gemmete JJ, Chaudhary N, Pandey A, et al. Treatment of carotid cavernous fistulas. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2010;12(1):43–53. doi: 10.1007/s11940-009-0051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serbinenko FA. Balloon catheterization and occlusion of major cerebral vessels. J Neurosurg. 1974;41:25–145. doi: 10.3171/jns.1974.41.2.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goto K, Hieshima GB, Higashida RT, et al. Treatment of direct carotid cavernous sinus fistulae. Various therapeutic approaches and results in 148 cases. Acta Radiol Suppl. 1986;369:576–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halbach VV, Higashida RT, Barnwell SL, et al. Transarterial platinum coil embolization of carotid-cavernous fistulas. Am J Neuroradiol. 1991;12:429–433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halbach VV, Hieshima GB, Higashida RT, et al. Carotid cavernous fistulae: indications for urgent treatment. Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149(3):587–593. doi: 10.2214/ajr.149.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi BJ, Lee TH, Kim CW, et al. Endovascular graft-stent placement for treatment of traumatic carotid cavernous fistulas. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2009;46(6):572–576. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2009.46.6.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayashi K, Suyama K, Nagata I. Traumatic carotid cavernous fistula complicated with intracerebral hemorrhage: case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2011;51(3):214–216. doi: 10.2176/nmc.51.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomez F, Escobar W, Gomez AM, et al. Treatment of carotid cavernous fistulas using covered stents: midterm results in seven patients. Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:1762–1768. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madan A, Mujic A, Daniels K, et al. Traumatic carotid artery-cavernous sinus fistula treated with a covered stents. J Neurosurg. 2006;104(6):969–973. doi: 10.3171/jns.2006.104.6.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elhammady MS, Wolfe SQ, Farhat H, et al. Onyx embolization of carotid-cavernous fistulas. J Neurosurg. 2010;112(3):589–594. doi: 10.3171/2009.6.JNS09132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kohyama S, Ishihara S, Yamane F, et al. Three-dimensional digital subtraction angiography for endovascular treatment of direct carotid-cavernous fistula - Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2010;50(5):404–406. doi: 10.2176/nmc.50.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo CB, Teng MM, Chang FC, et al. Transarterial balloon-assisted n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate embolization of direct carotid cavernous fistulas. Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27(7):1535–1540. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]