Abstract

Study Objectives:

We examined the association between social factors and sleep difficulties among the victims remaining at home in the Ishinomaki area after the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami and identified potentially modifiable factors that may mitigate vulnerability to sleep difficulties during future traumatic events or disasters.

Design:

A cross-sectional household survey was conducted from October 2011 to March 2012 (6-12 mo after the disaster) in the Ishinomaki area, Japan. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were used to examine associations between social factors and sleep difficulties.

Participants:

We obtained data on 4,176 household members who remained in their homes after the earthquake and tsunami.

Interventions:

N/A.

Results:

Sleep difficulties were prevalent in 15.0% of the respondents (9.2% male, 20.2% female). Two potentially modifiable factors (lack of pleasure in life and lack of interaction with/visiting neighbors) and three nonmodifiable or hardly modifiable factors (sex, source of income, and number of household members) were associated with sleep difficulties. Nonmodifiable or hardly modifiable consequences caused directly by the disaster (severity of house damage, change in family structure, and change in working status) were not significantly associated with sleep difficulties.

Conclusions:

Our data suggest that the lack of pleasure in life and relatively strong networks in the neighborhood, which are potentially modifiable, might have stronger associations with sleep difficulties than do nonmodifiable or hardly modifiable consequences of the disaster (e.g., house damage, change in family structure, and change in work status).

Citation:

Matsumoto S; Yamaoka K; Inoue M; Muto S. Social ties may play a critical role in mitigating sleep difficulties in disaster-affected communities: a cross-sectional study in the Ishinomaki area, Japan. SLEEP 2014;37(1):137-145.

Keywords: Cross-sectional household survey, Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, natural disaster, sleep difficulties, social network

INTRODUCTION

Sleep difficulties are one of the most common presenting symptoms after disastrous events,1 and are known to have detrimental effects on psychological health. For example, sleep difficulties are a symptom of and may be a risk factor for post-traumatic stress disorder2,3 and other mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety.4–6 Sleep difficulties may also be a predictor of suicidal behavior in depressed patients.7,8 The chronic nature of sleep difficulties and the associated impaired daytime functioning9–11 can impose an excessive economic burden on disaster-affected communities, affecting direct and indirect costs.12,13

The Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, which occurred on March 11, 2011, devastated sizeable areas of the Pacific coastal regions of eastern Japan and jeopardized the fundamental aspects of survivors' lives and their communities. The earthquake triggered powerful tsunami waves that reached heights of up to 15 m (50 feet) in the fishery port of Onagawa and 5 m (16 feet) in the Ishinomaki area ports.14 The Ishinomaki area in Miyagi Prefecture was destroyed or heavily damaged by the tsunami.

Disasters often result in tremendous changes in the living situations of survivors and disrupt social ties in communities.15 However, less is known about the role of social factors in the sleep difficulties experienced by disaster-affected populations. Several epidemiological studies have investigated the association between sleep difficulties and socioeconomic factors in the general population, and lower income,16–19 less education,17,19 and disadvantages in employment (unemployment,16,17 engagement in manual labor,20 and lower employment grades21) were found to be associated with sleep difficulties. Others have focused on a wider range of social factors, including social networks and social capital in relation to sleep difficulties. Nomura et al. focused on social capital in relation to self-reported sleep difficulties and reported that lack of social support was associated with sleep difficulties.22 Steptoe et al. reported that negative psychosocial factors, including financial strain, social isolation, low emotional support, negative social interactions, and psychological distress, were related to sleep difficulties.23 We believe that it is important to investigate the association between various social factors and sleep difficulties in a disaster-affected population given the major psychosocial effect of sleep difficulties and the various effects of natural disasters on social factors (e.g., place of residence, finances, and social ties among residents).

The effects of social factors on health, referred to as social determinants of health, have been attracting increasing attention. Among the models of health determinants, that of Dahl-gren and Whitehead, which has been cited widely, highlights the existence of a broader range of determinants of health that are beyond the direct influence of individuals.24 This model describes determinants of health in terms of layers, beginning at the individual level (e.g., biology and individual behavior) and extending to societal levels (e.g., social and community networks; living and working conditions; and general socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental conditions; Figure 1). We considered this model useful for providing a framework for organizing data on social factors as well as for discussing the effects on health.

Figure 1.

Dahlgren and Whitehead's model of determinants of health. Source: Dahlgren and Whitehead (2006).

In this study, we sought to examine the association between social factors and sleep difficulties in the wake of a natural disaster using data from a survey in the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami-affected area using Dahlgren and White-head's model. In particular, we sought to identify potentially modifiable factors associated with sleep difficulties that could be targeted for interventions and strategies that would reduce vulnerability to sleep difficulties and the associated adverse psychosocial consequences of future traumatic events or disasters.

METHODS

Participants

After the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, a face-to-face survey using a semistructured questionnaire was carried out in the Ishinomaki area between October 2011 and March 2012 (6-12 mo after the disaster) by interviewers belonging to the Health and Life Revival Council in the Ishinomaki district (RCI).25 The RCI, which was composed of a number of private bodies, including a clinic and nonprofit organizations, started its activities in November 2011 and aimed to provide rapid and appropriate support in response to the needs of stay-at-home victims in the Ishinomaki area who suffered during the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. In total, 326 interviewers visited each remaining house in the area, including those with severe damage, and conducted interviews of earthquake/ tsunami victims who remained at home. All interviewers were trained using both an instruction manual and on-the-job learning by attending home visits with experienced interviewers.

The primary objective of the survey was to assess the living conditions and health status of stay-at-home victims to provide appropriate support. This target population was selected because victims staying at home were provided less support by governmental agencies than those living in temporary shelters. This population of approximately 8,700 households remained at home despite serious damage to their houses. Many were, in fact, living only on the second floor of their houses because the tsunami had swept out the first floor completely.

The questionnaire comprised the following three sections: household demographics, social backgrounds, and the health condition of the individual most in need of medical support. We obtained data on 4,176 household members who agreed to be interviewed with the written form. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Teikyo University (reference number: 12-079).

Measurements

Sleep Difficulties

The presence of sleep difficulties was evaluated with the question: “Do you have any psychological symptoms?” The following seven possible responses were provided: (1) sleep difficulties, (2) depressive mood, (3) disturbed living routine, (4) loss of interest or joy, (5) sense of an unsatisfactory life, (6) sense of hopelessness, and (7) suicidal ideation. Other symptoms mentioned by the respondents were recorded in (8) as “other.” The respondents could choose as many items as they thought applicable. Respondents who selected (1) sleep difficulties were regarded as having sleep difficulties, and others were regarded as not having sleep difficulties.

All questionnaires, including those reporting the presence of psychological symptoms, were answered by the representatives of households. Thus, the presence of sleep difficulties was not necessarily reported by the individual who experienced the psychological symptoms. During the period of our survey, many of the victims living at home were still compelled to live and sleep in restricted spaces in their houses, which had been severely damaged by the earthquake and tsunami. They were also much more concerned about how others were coping with the difficulties in their lives than they had been before the disaster. We thought it was reasonable to assume that each household member would know whether others in the household were sleeping well. For this reason, we identified sleep difficulties based on reports made by the representatives of the household about concerned individuals in addition to those based on reports by and about the individuals themselves.

Demographics

The sex and age of the person who reported psychological symptoms were obtained as basic demographic information. Age was treated as a continuous variable, and age was analyzed in 10-y units.

Social Determinants of Health

We classified social factors into three sets of categories in accordance with the model of the determinants of health introduced by Dahlgren and Whitehead (Figure 1): (1) social and community networks; (2) living and working conditions; and (3) general socioeconomic, cultural, environmental conditions.24

Social and community networks were assessed by means of six items: having pleasure in life, having someone to consult about problems (even by phone), having friends in the neighborhood, having someone to whom to report an emergency (even by phone), having interaction with neighbors, and having routine chances to talk with others. We included having pleasure in life as a variable related to social and community networks given that having pleasure in life is facilitated by experiencing activities, communication, and the sense of inclusion provided by participation in social and community networks. Thus, we treated having pleasure in life as a consequence of engaging in social and community networks. Interaction with neighbors was rated in five categories: (0) none; (1) only greetings; (2) only chatting; (3) visiting one another; and (4) exchanging favors. The other items were responded to dichotomously.

Living and working conditions were assessed by means of information about the source of the household's income, the number of household members, households that comprised only those who were individuals age 65 y or older (hereafter referred to as elderly household), changes in family structure or working status, and local government recognition of the severity of house damage. The source of income was selected from the following four categories: (1) only salary; (2) only pension; (3) public livelihood assistance; and (4) pension and salary. The number of household members was divided into four categories: (1) one; (2) two; (3) three; and (4) more than three. The severity of house damage was rated on a five-point scale: (0) none; (1) partially destroyed; (2) half destroyed; (3) largely destroyed; and (4) totally destroyed. The other items were responded to dichotomously.

General socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental conditions were assessed by means of information on the residential area (Table 1), the existence of a community hall in the residential area, and the existence of a community. The residential area was divided into eight categories, and other items were responded to dichotomously. We ascertained the existence of a community hall by asking only whether there were any community halls in the residential area because the earthquake and tsunami destroyed many of these structures, which are typically available to residents as places to gather. We determined the existence of a community as an informal association or group of people who were loosely connected in a neighborhood by asking interviewees.

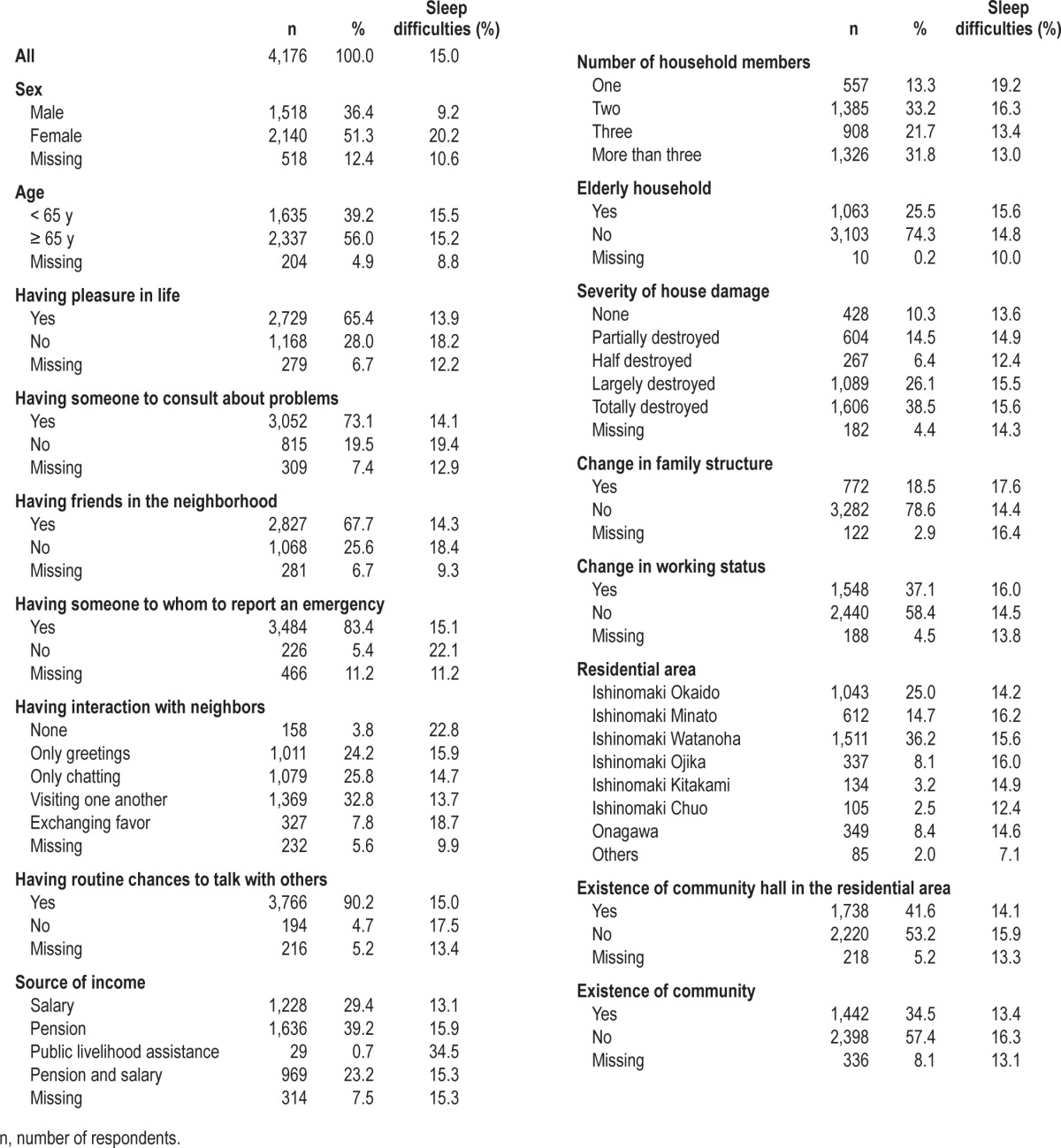

Table 1.

Characteristics of respondents and sleep difficulties prevalence

Statistical Analyses

Logistic regression analyses were used to examine statistical associations between the outcome variable (sleep difficulties) and the explanatory variables, including sex, age, having pleasure in life, having someone to consult about problems, having friends in the neighborhood, having someone to whom to report an emergency, having interaction with neighbors, having routine chances to talk with others, source of income, number of household members, elderly household, change in family structure, change in working status, severity of house damage, residential area, existence of community hall(s) in the residential area, and existence of community. First, we conducted a univariate analysis for each explanatory variable. Next, we calculated the odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) adjusted by all variables (multivariate model), which we treated as the primary analysis. In these models, missing data were excluded from the analysis.

We also conducted three supplementary analyses. The first analysis applied the multivariate model to the data on the presence of sleep difficulties that were obtained from and about the interviewees themselves. Second, we applied a multivariate model using a stepwise method for all variables (inclusion and exclusion criteria = 0.3 for each) to improve statistical power. Finally, a multiple imputation (MI) method was used for the final model under the assumption of missing at random to handle missing data.26

We treated all variables, except age, as categorical variables (dummy coded). All analyses were performed using the SAS Enterprise Guide software (version 4.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All tests were two sided, with a significance level of 5%.

RESULTS

The characteristics of respondents and the prevalence of sleep difficulties are shown in Table 1. Female respondents comprised 51.3% of participants. The mean age (standard deviation [SD]) was 65.5 (16.2) y, and nearly half were age 65 y or older. One-person households accounted for 13.3% of the respondents, whereas about one-fourth of households (25.5%) consisted only of individuals age 65 y or older. A total of 38.5% of respondents' houses were recognized by the local government as being totally destroyed. Moreover, 18.5% of respondents experienced a change in family structure, whereas 37.1% experienced a change in working status due to the earthquake and tsunami. The prevalence of sleep difficulties was 15.0% (9.2% male, 20.2% female). Females, those who lived on public livelihood assistance, those who did not have anyone to whom to report an emergency, and those who did not have interaction with neighbors were more likely to report sleep difficulties. The proportions of missing values were below 10.0%, except for sex (12.4%) and having someone to whom to report an emergency (11.2%).

The multivariable analysis (Table 2) showed that being female (OR = 2.67, 95% CI = 2.07-3.46 versus male sex), not having pleasure in life (OR = 1.37, 95% CI = 1.07-1.76 versus having pleasure in life), living on a pension (OR = 1.58, 95% CI = 1.09-2.27 versus living on salary) or public livelihood assistance (OR = 4.40, 95% CI = 1.53-12.65 versus living on salary), and having one person (OR = 1.69, 95% CI = 1.07-2.67 versus more than three) or two persons (OR = 1.44, 95%CI = 1.04-1.99 versus more than three) in a household were negatively associated with sleep. However, having interaction with neighbors (visiting one another) (OR = 0.42, 95% CI = 0.24-0.74 versus not having interaction with neighbors) was positively associated with sleep. Factors that were related directly to the disaster, such as severity of house damage, change in family structure, and change in working status, were not significantly associated with sleep difficulties.

Table 2.

Logistic regression results: Crude and adjusted odds ratios of sleep difficulties and 95% confidence intervals

The supplementary analyses, in which we used the multivariate model with more strictly defined parameters for sleep difficulties (i.e., the presence of sleep difficulties was coded only when they were reported and experienced by the interviewees themselves), yielded results similar to those produced by the primary ones. The directions of the effects of all variables were unchanged (Table 3). Further, the stepwise regression method and the MI method applied to the multivariate model also showed similar tendencies, and the directions of the effects on the variables were the same as those in the primary multivariate model, although some of the variables were no longer statistically significant with the MI method (data not shown).

Table 3.

Supplementary analysis: Multivariate model using only the data on the presence of sleep difficulties obtained from and experienced by the interviewees themselves

DISCUSSION

We assessed the role of a wide range of social factors associated with sleep difficulties in a large population-based sample of stay-at-home victims of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. The analysis identified potentially modifiable factors related to social and community networks (not having pleasure in life, not having interaction with/visiting neighbors) that were associated with sleep difficulties. Three nonmodifiable or hardly modifiable factors (sex, source of income, number of household members) were also associated with sleep difficulties. In contrast, nonmodifiable or hardly modifiable consequences caused directly by the disaster, such as severity of house damage, change in family structure, and change in working status, were not significantly associated with sleep difficulties.

Comparison with Other Studies

Sleep difficulties are widely recognized as one of the most common symptoms after disastrous events. Kato et al. reported that sleep disturbance was the most common symptom after the 1995 Hanshin-Awaji earthquake in Japan among 143 individuals (63% at 3 w postdisaster, 46% at 8 w).27 Similarly, Varela et al. reported that among 305 individuals 1 y after the 1999 Athens earthquake in Greece, 55% developed sleep disorders, 60% of which were insomnia.28 Compared with those reports, the prevalence of sleep difficulties we report here is by no means high. Rather, it was similar to that in the general Japanese population, which was reported to be 11.7% for males and 14.5% for females by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in 2010.29 Other studies reported prevalences of 4% to 21%.30–32 These discrepancies may be due to variations in the interval between the earthquake and the date of the survey.

Sleep disturbances are a part of the normal response to trauma but usually diminish with time.3 Our survey was conducted at least 6 mo after the earthquake, which might have been enough time for survivors to overcome sleep difficulties. Differences in sample populations could also explain our data. Our survey targeted victims staying at home; the prevalence of sleep difficulties in these individuals might differ from those staying in temporary shelters. A systematic review of the postdisaster relocation literature suggested that relocated individuals are more likely to experience psychological morbidity postdisaster, although some results were inconsistent.33 Another study reported that increased distance from family and/or friends following an earthquake evacuation was associated with psychological distress.34 Cumulative stress due to lack of privacy in institutional accommodations, unfamiliar living environments in temporary shelters, and disruption of social networks increased the risk of sleep difficulties in survivors. Moreover, the different definitions of sleep difficulties among these reports, including ours, make it difficult to directly compare the prevalence among studies.

We assessed social and community networks by means of six variables, some of which may have common features. We assumed that the use of variables reflecting various aspects of social and community networks would enable us to determine the aspects of such networks that are related to sleep difficulties. Our data showed that two variables related to social and community network (not having pleasure in life and not having interaction with/visiting neighbors) had significant associations with sleep difficulties which was consistent with previous reports of this association in the general population23,35,36, although these did not use the same variables related to social and community networks with ours.

We included having pleasure in life in social and community networks because we considered it to be a consequence of participation in such networks. Given that a lack of pleasure in life was associated with sleep difficulties, the presence of pleasure in life may ease psychological distress and loneliness caused by the disaster, which might promote better sleep. Another explanation might be that people with sleep difficulties are more susceptible to a loss of pleasure in life. Because of the cross-sectional design of this study, however, we could not determine cause-and-effect relationships.

On the other hand, interactions with/visiting neighbors had a greater association with sleep difficulties than did other variables related to social and community networks. Especially, interactions with/visiting neighbors and having friends in the neighborhood were both related to ties with neighbors and were significant in the univariate model, but only interactions/visits with neighborhoods but not having friends in the neighborhood was significant in the multivariate model. One of the explanations might be due to the different levels of strength/quality of ties. Given the timing of the survey (6-12 mo after the disaster), victims staying at home could get most goods that were essential to their individual daily lives (food and water); however, some of their houses were scattered widely, and the residents tended to be isolated. In this context, our results related to interaction with/visiting neighbors may suggest that the relatively stronger relationships generated by neighborhoods that enable residents to spend time with others on a face-to-face basis versus the relatively weaker relationships associated with neighborhoods without such characteristics may help victims feel at ease in the community and encourage better sleeping habits, especially during this time period after a disaster. However, further research is needed to examine this issue.

In terms of comparisons between our findings and those of other studies that have targeted disaster-affected populations, Oyama et al. investigated factors associated with psychological distress 3 y after the 2004 Niigata-Chuetsu earthquake in Japan and reported that poor or loss of contact with people in the community was associated with psychological distress.37 Stanke et al. reviewed the effects of flooding on mental health and found that the psychological needs of survivors were met by people who were close to them and that a smaller proportion of people required specialized mental health care.38 These studies did not investigate the role of social factors in sleep difficulties, although they may nonetheless be somewhat comparable to our study given that sleep difficulties are closely linked to psychological distress and mental health. Sharing information and feelings, as well as deriving a sense of belonging or security, through social networks in local communities might alleviate anxiety, stress, and sorrow in survivors and reduce vulnerability to sleep difficulties.

Social capital has recently gained attention with regard to disaster responses and the recovery of communities.39–41 It is closely linked with social networks and was defined by Putnam as “the social networks and the norms of trustworthiness and reciprocity that arise from them.”42 The Sendai Report, which was developed to support the Sendai Dialogue, a special event on mainstreaming disaster risk management that was hosted by the Japanese government and the World Bank in October 2012, argued for the need to build social capital in communities to promote disaster resilience at the local level.43 Because sleep difficulties cause psychosocial as well as physical impairment of individuals, if a social network reduces the risk of sleep difficulties, it could help people stay physically, mentally, and socially healthy. We assume that healthier people will strengthen communities' human capital, which will be a driving force in the disaster response and the recovery of communities. Reducing the risk of sleep difficulties after disasters at the individual level would be expected to promote recovery in disaster-affected communities.

In our study, females and people with lower economic status were more likely to report sleep difficulties, which is consistent with previous reports.16–19,44 Contrary to previous studies,45 however, increased age was not significantly associated with sleep difficulties in our final multivariate analysis. This may be because our survey targeted victims staying at home, and our population included more relatively healthy elderly persons than did other studies.

It was surprising that changes in family structure and working status, and the severity of house damage were not significantly associated with sleep difficulties because previous studies did associate those variables with psychological distress.37,46,47 In particular, the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami brought destruction along the Pacific coastline of eastern Japan. It severely damaged a number of fishing ports and aquafarming facilities where many residents were employed and so took them away from their jobs. Thus, we hypothesized that changes in working status would significantly affect sleep difficulties. The lack of association might be due to the time interval between the event and the survey. Furthermore, considering the results of the final model, another explanation for the lack of association might relate to the role of social capital and community networks. Indeed, these may protect against sleep difficulties and override the negative association between sleep difficulties and changes in family structure and/or working status and/ or the severity of house damage. Further research is needed to analyze our results and interpretations.

Limitations

The association between a wide range of social factors and sleep difficulties has not been previously investigated in disaster-affected populations. However, this study has several limitations. First, this study used a cross-sectional design, and so we are unable to determine any causal relationship between social factors and sleep difficulties. Moreover, our survey was conducted 6-12 mo after the earthquake, and so the findings might not be applicable to other periods after a disaster. However, the time period used in the current analysis was relevant to the population studied. Displaced disaster victims must cope with moving to a strange location, but they do not have to cope with housing damage. Alternately, disaster victims who stay at home must cope with housing damage, but they do not need to cope with moving to a strange location. Thus, in both populations, the long-term psychological outcomes are most relevant. Second, our sample population consisted exclusively of disaster-affected victims who stayed at home. Our results, therefore, might not be applicable to other types of victims, such as those staying in temporary shelters or those who moved to other districts to stay in temporary housing. A comparison of social factors associated with sleep difficulties among various populations staying in different types of housing is thus necessary. Third, our sample was selected by a nonrandom method because the purpose of the survey was to urgently assess the needs of victims staying at home. Random sampling is recommended in future studies to verify our findings. Fourth, the presence of sleep difficulties was reported not only by the subject but also by representatives of the household on behalf of the concerned subject, which could bias the results. However, even when we used only those data on the presence of sleep difficulties that concerned the interviewees themselves, the multivariate model showed results similar to those produced by the primary analysis (Table 3). Fifth, the lack of sleep difficulties data prior to the disaster prevented controlling for predisaster sleep difficulties in the analyses. Sixth, we simply asked the participants if they had sleep difficulties, which might have been an inadequate way to measure this phenomenon. There are various methodologies to identify sleep difficulties (time frame and frequency),48 and future studies should use multi-item questionnaires to ensure the validity of measurements.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite its limitations, this study has important implications regarding social factors related to sleep difficulties arising in the wake of the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. Our findings indicate that the lack of pleasure in life and relatively strong networks in the neighborhood, which are potentially modifiable, might have stronger associations with sleep difficulties than do non- or hardly modifiable consequences caused directly by the disaster, such as house damage, changes in family structure, and changes in work status. Efforts to build ties among family members, neighbors, and friends might be one possible way to mitigate vulnerability to sleep difficulties and related adverse health outcomes, improve quality of life, reduce the economic burden to society, and promote recovery of disaster-affected communities. Individuals engaged in the recovery of communities, including policy makers, should consider building social networks and capital as well as physical capital.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This study was supported financially by the Japan Public Health Society through a Special Grant for public health in the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2012. The granting agency had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the manuscript, or decision to submit the manuscript. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lavie P. Sleep disturbances in the wake of traumatic events. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1825–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babson KA, Feldner MT. Temporal relations between sleep problems and both traumatic event exposure and PTSD: a critical review of the empirical literature. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harvey AG, Jones C, Schmidt DA. Sleep and posttraumatic stress disorder: a review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23:377–407. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor DJ, Lichstein KL, Durrence HH, Reidel BW, Bush AJ. Epidemiology of insomnia, depression, and anxiety. Sleep. 2005;28:1457–64. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.11.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breslau N, Roth T, Rosenthal L, Andreski P. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: a longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:411–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ford DE, Kamerow DB. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders. An opportunity for prevention? JAMA. 1989;262:1479–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.11.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ağargün MY, Kara H, Solmaz M. Sleep disturbances and suicidal behavior in patients with major depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:249–51. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singareddy RK, Balon R. Sleep and suicide in psychiatric patients. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2001;13:93–101. doi: 10.1023/a:1016619708558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roth T, Ancoli-Israel S. Daytime consequences and correlates of insomnia in the United States: results of the 1991 National Sleep Foundation Survey. II. Sleep. 1999;22:S354–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alapin I, Fichten CS, Libman E, Creti L, Bailes S, Wright J. How is good and poor sleep in older adults and college students related to daytime sleepiness, fatigue, and ability to concentrate? J Psychosom Res. 2000;49:381–90. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kucharczyk ER, Morgan K, Hall AP. The occupational impact of sleep quality and insomnia symptoms. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16:547–59. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Godet-Cayré V, Pelletier-Fleury N, Le Vaillant M, Dinet J, Massuel MA, Léger D. Insomnia and absenteeism at work. Who pays the cost? Sleep. 2006;29:179–84. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daley M, Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Grégoire JP, Savard J. The economic burden of insomnia: direct and indirect costs for individuals with insomnia syndrome, insomnia symptoms, and good sleepers. Sleep. 2009;32:55–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Port and Airport Research Institute (PARI), Japan. Executive Summary of Urgent Field Survey of Earthquake and Tsunami Disasters by the 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku Earthquake. 2011. http://www.pari.go.jp/en/files/items/3496/File/20110325.pdf. Retrieved on 5 Oct, 2013.

- 15.Tsuda M, Tamaki M. Shizennsaigai to kokusai kyoryoku (in Japanese) Tokyo: Shinhyoron; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sutton DA, Moldofsky H, Badley EM. Insomnia and health problems in Canadians. Sleep. 2001;24:665–70. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.6.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grandner MA, Patel NP, Gehrman PR, et al. Who gets the best sleep? Ethnic and socioeconomic factors related to sleep complaints. Sleep Med. 2010;11:470–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel NP, Grandner MA, Xie D, Branas CC, Gooneratne N. “Sleep disparity” in the population: poor sleep quality is strongly associated with poverty and ethnicity. BMC Publ Health. 2010;10:475. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore PJ, Adler NE, Williams DR, Jackson JS. Socioeconomic status and health: The role of sleep. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:337–44. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200203000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green MJ, Espie CA, Hunt K, Benzeval M. The longitudinal course of insomnia symptoms: inequalities by sex and occupational class among two different age cohorts followed for 20 years in the west of Scotland. Sleep. 2012;35:815–23. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sekine M, Chandola T, Martikainen P, McGeoghegan D, Marmot M, Kagamimori S. Explaining social inequalities in health by sleep: the Japanese civil servants study. J Public Health (Oxf) 2006;28:63–70. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdi067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nomura K, Yamaoka K, Nakao M, Yano E. Social determinants of self-reported sleep problems in South Korea and Taiwan. J Psychosom Res. 2010;69:435–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steptoe A, O'Donnell K, Marmot M, Wardle J. Positive affect, psychological well-being, and good sleep. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:409–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2006. Levelling up (part 2): a discussion paper on European strategies for tackling social inequities in health. [Google Scholar]

- 25. http://rc-ishinomaki.jp/ (in Japanese). Retrieved on 10 Jan, 2013.

- 26.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kato H, Asukai N, Miyake Y, Minakawa K, Nishiyama A. Post-traumatic symptoms among younger and elderly evacuees in the early stages following the 1995 Hanshin-Awaji earthquake in Japan. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93:477–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb10680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varela E, Koustouki V, Davos CH, Eleni K. Psychological consequences among adults following the 1999 earthquake in Athens, Greece. Disasters. 2008;32:280–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2008.01039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010 (in Japanese) http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/houdou/2r98520000020qbb-att/2r98520000021c19.pdf. Retrieved on 10 Dec, 2012.

- 30.Kageyama T, Kabuto M, Nitta H, et al. A population study on risk factors for insomnia among adult Japanese women: a possible effect of road traffic volume. Sleep. 1997;20:963–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim K, Uchiyama M, Okawa M, Liu X, Ogihara R. An epidemiological study of insomnia among the Japanese general population. Sleep. 2000;23:41–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nomura K, Yamaoka K, Nakao M, Yano E. Impact of insomnia on individual health dissatisfaction in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Sleep. 2005;28:1328–32. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.10.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uscher-Pines L. Health effects of relocation following disaster: a systematic review of the literature. Disasters. 2009;33:1–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2008.01059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bland SH, O'Leary ES, Farinaro E, et al. Social network disturbances and psychological distress following earthquake evacuation. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185:188–94. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199703000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts RE, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA, Strawbridge WJ. Sleep complaints and depression in an aging cohort: A prospective perspective. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:81–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.157.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yao KW, Yu S, Cheng SP, Chen IJ. Relationships between personal, depression and social network factors and sleep quality in community-dwelling older adults. J Nurs Res. 2008;16:131–9. doi: 10.1097/01.jnr.0000387298.37419.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oyama M, Nakamura K, Suda Y, Someya T. Social network disruption as a major factor associated with psychological distress 3 years after the 2004 Niigata-Chuetsu earthquake in Japan. Environ Health Prev Med. 2012;17:118–23. doi: 10.1007/s12199-011-0225-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stanke C, Murray V, Amlôt R, Nurse J, Williams R. The effects of flooding on mental health: Outcomes and recommendations from a review of the literature. PLoS Curr. 2012;4 doi: 10.1371/4f9f1fa9c3cae. e4f9f1fa9c3cae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakagawa Y, Shaw R. Social capital: A missing link to disaster recovery. Int J Mass Emerg Disasters. 2004;22:5–34. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koh HK, Cadigan RO. Disaster preparedness and social capital. In: Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Kim D, editors. Social Capital and Health. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 273–85. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aldrich DP. The power of people: social capital's role in recovery from the 1995 Kobe earthquake. Natural Hazards. 2011;56:595–611. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Putnam RD. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43.The Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR), the World Bank, Government of Japan. The Sendai report: managing disaster risks for a resilient future. 2012. http://www.gfdrr.org/sites/gfdrr.org/files/Sendai_Report_051012.pdf. Retrieved on 25 Dec, 2012.

- 44.Soares CN. Insomnia in women: an overlooked epidemic? Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8:205–13. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crowley K. Sleep and sleep disorders in older adults. Neuropsychol Rev. 2011;21:41–53. doi: 10.1007/s11065-010-9154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kristensen P, Weisæth L, Heir T. Bereavement and mental health after sudden and violent losses: a review. Psychiatry. 2012;75:76–97. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2012.75.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cerdá M, Paczkowski M, Galea S, Nemethy K, Péan C, Desvarieux M. Psychopathology in the aftermath of the Haiti earthquake: a population-based study of posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression. Depress Anxiety. 2012;30:413–24. doi: 10.1002/da.22007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:97–111. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]