Abstract

Study Objectives:

Sleep disordered breathing (SDB) in children is associated with detrimental neurocognitive and behavioral consequences. The long term impact of treatment on these outcomes is unknown. This study examined the long-term effect of treatment of SDB on neurocognition, academic ability, and behavior in a cohort of school-aged children.

Design:

Four-year longitudinal study. Children originally diagnosed with SDB and healthy non-snoring controls underwent repeat polysomnography and age-standardized neurocognitive and behavioral assessment 4y following initial testing.

Setting:

Melbourne Children's Sleep Centre, Melbourne, Australia.

Participants:

Children 12-16 years of age, originally assessed at 7-12 years, were categorized into Treated (N = 12), Untreated (N = 26), and Control (N = 18) groups.

Interventions:

Adenotonsillectomy, Tonsillectomy, Nasal Steroids. Decision to treat was independent of this study.

Measurements and Results:

Changes in sleep and respiratory parameters over time were assessed. A decrease in obstructive apnea hypopnea index (OAHI) from Time 1 to Time 2 was seen in 63% and 100% of the Untreated and Treated groups, respectively. The predictive relationship between change in OAHI and standardized neurocognitive, academic, and behavioral scores over time was examined. Improvements in OAHI were predictive of improvements in Performance IQ, but not Verbal IQ or academic measures. Initial group differences in behavioral assessment on the Child Behavior Checklist did not change over time. Children with SDB at baseline continued to exhibit significantly poorer behavior than Controls at follow-up, irrespective of treatment.

Conclusions:

After four years, improvements in SDB are concomitant with improvements in some areas of neurocognition, but not academic ability or behavior in school-aged children.

Citation:

Briggs SN; Vlahandonis A; Anderson V; Bourke R; Nixon GM; Davey MJ; Horne RSC. Long-term changes in neurocognition and behavior following treatment of sleep disordered breathing in school-aged children. SLEEP 2014;37(1):77-84.

Keywords: Children, sleep disordered breathing, treatment, cognitive function, behavior

INTRODUCTION

Sleep disordered breathing (SDB) describes a continuum of respiratory disturbance ranging from primary snoring (PS) to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). PS is characterized by snoring without associated gas exchange abnormalities or sleep disturbance. Characteristics of OSA include obstructive apneas, intermittent hypoxia, hypercarbia, and repeated arousals.1 SDB is common in children. Snoring prevalence rates are reported at 10% to 15%, with 3% having OSA.2 Cross-sectional studies have shown that school-aged children with SDB, irrespective of severity, are at risk of neurocognitive and academic deficits3–8 and behavioral problems3,9–11 compared to controls.

Childhood OSA is most commonly the result of large tonsils and adenoids relative to airway size,12 with adenotonsillectomy (AT) the most common treatment. A number of pediatric studies have examined the effects of AT on neurocognitive and academic outcomes up to 12 months after surgery,6,7,13–18 but only three included a control group for comparison.6,13,16 In those studies, sustained attention and working memory consistently showed improvements after treatment but verbal knowledge, language development, visuospatial ability, and generalized intelligence did not. Behavioral outcomes show more consistent positive results post-treatment with improvements in hyperactivity, oppositional, internalizing, and externalizing behavior.13,16,19

Longitudinal designs beyond 12 months examining the effects of treatment of OSA on daytime functioning in children are scarce. It may be that a longer period is required to see any discernible improvement in more complex neurocognitive functions, such as executive function and IQ, due to the diffuse cortical networks underpinning these high-level skills.20 In addition, while AT is the recommended treatment for OSA, it is rarely performed in children with PS. As equivalent neuro-cognitive and behavioral deficits are seen in children with PS as those with OSA,11,21,22 this begs the question: what happens to children who are not treated? Does their SDB naturally improve with age with parallel gains in daytime functioning? Do deficits persist or even worsen? A recent study reported that the likelihood of behavioral problems increased with persistent SDB when tested after periods of four and seven years.23 Similar studies examining neurocognitive functioning are not yet available. As only a small proportion of children with SDB are treated clinically, understanding the effect of changes in SDB over time on daytime functioning has important implications for clinical management.

This study aimed to examine the long term effect of treatment and non-treatment of SDB on neurocognition, academic ability and behavior in a cohort of school-aged children. We hypothesized that given more time following treatment, neuro-cognition, academic ability, and behavior would improve with improvement in SDB.

METHODS

Subjects

Monash University and Southern Health Human Research Ethics Committees provided ethical approval. Written informed consent and verbal assent were obtained from parents and children, respectively. No monetary incentive was provided.

Participants were initially enrolled in a study examining the effects of SDB on blood pressure, cardiovascular control, neurocognition and behavior between July 2004 and December 2008.21,22,24–27 At the initial study (Time 1), we recruited children aged 7-12 years with clinically suspected SDB (N = 116) and healthy non-snoring community controls (N = 39). Children taking medications or with medical conditions known to affect sleep or neurobehavioral function were excluded. All participants were invited to return for this study (Time 2) between 2008 and 2012. Response rate was 35% for children with previously diagnosed SDB and 54% for controls. All returning children underwent an identical protocol to Time 1.

Protocol

Each child underwent a full overnight polysomnography (PSG) study using standard clinical pediatric techniques and a commercially available sleep system (Compumedics, Melbourne, Australia). Height and weight were recorded to calculate body mass index (BMI), adjusted for sex and age.28

Electroencephalograms (EEG: C3/A2, C4/A1, O1/A2, O2/ A1), electroculograms, submental electromyogram, electrocardiogram, left and right leg electromyogram, and body position were recorded. Oxygen saturation (SpO2) was measured by pulse oximetry and thoracic and abdominal breathing movements were recorded via uncalibrated respiratory inductance plethysmography. End-tidal and transcutaneous carbon dioxide were recorded. Airflow was measured via nasal pressure and oronasal thermistor. Continuous blood pressure was recorded using finger photoplethysmography (Finometer, Finapres Medical Systems, Arnhem, The Netherlands) but is not reported here.

Sleep scoring was performed in 30-s epochs following Rechtschaffen and Kales criteria,29 the gold standard at Time 1. Scoring was conducted by trained technicians who maintained a concordance rate > 85% for both sleep and respiratory events. Cortical and subcortical arousals were scored according to American Sleep Disorders Manual and the International Paediatric Work Group on Arousals criteria.30,31

The arousal index (ArI) was defined as the total number of cortical and subcortical activations per hour (/h) of total sleep time (TST). The respiratory disturbance index (RDI) was the total number of obstructive, central and mixed apneas, and hypopneas/h of TST. The obstructive apnea hypopnea index (OAHI) was defined as the number of obstructive apneas, hypopneas and mixed apneas/h of TST. SpO2 desaturations ≥ 3% was defined as the number of times/h the oxygen saturation dropped ≥ 3% when associated with a central or obstructive respiratory event. At the time of their initial PSG study, children were diagnosed as Control: OAHI ≤ 1 event/h with no reported history of snoring and no snoring on PSG; Primary snoring (PS): OAHI ≤ 1 event/h with a clinical history of snoring; Mild OSA: OAHI > 1- ≤ 5 events/h; Moderate-Severe OSA (MS OSA): OAHI > 5 events/h.

Within 3 weeks of the PSG, neurocognitive assessments were completed in the child's home. Regular sleep patterns were confirmed with a 7-day parent-report sleep/wake diary. Trained psychologists conducted the assessments which consisted of measures of intellectual ability (Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence: WASI),32 and academic functioning (Wide Range Achievement Test-3: WRAT).33 The WASI provides 2 intelligence quotient (IQ) domains—Verbal IQ and Performance IQ—which combined give an indication of global IQ, labelled Full-Scale IQ. Verbal IQ assesses expressive vocabulary, verbal knowledge, verbal concept formation, and verbal reasoning. Performance IQ assesses spatial visualization, visual-motor coordination, abstract conceptualization, and nonverbal fluid reasoning. The WRAT assesses Word Reading, Spelling, and Arithmetic. Standardized scores are provided for the WASI and WRAT (mean 100 ± 15).

Behavioral questionnaires were completed by the parents during the PSG and included the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)34 and Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF).35 The CBCL contains 3 summary subscales—Internalizing, Externalizing and Total Problem Behavior—which encompass scales of anxiousness, withdrawal/depression, somatic complaints, social problems, thought problems, attention problems, rule-breaking behavior, and aggressive behavior. The BRIEF also consists of 3 indices: Behavioral Regulation Index (BRI), Global Executive Composite (GEC), and Meta-cognition Index (MI). These are composed of 8 clinical scales relating to behaviors associated with executive function such as working memory, planning, and emotional control. The 3 composite scales for both the CBCL and BRIEF, converted to age-standardized T-scores (mean 50 ± 10), are reported.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic differences between groups at Time 2 were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and χ2 analysis for categorical variables. Group differences in sleep measures over time were analyzed using one-way repeated measures (RM) ANOVA. Wake after sleep onset (WASO), ArI, OAHI, and SpO2 desaturations ≥ 3% showed severe positive skew. WASO was corrected using logarithmic transformations. Respiratory and arousal parameters remained skewed after transformation, and thus nonparametric statistics were performed to determine group differences at Time 1 and 2 and overall change over time. Correlational analysis confirmed maternal education as a covariate of neurocognition and behavior.

To account for both between- and within-subject variance, a linear mixed-model analysis was used to determine whether inter-individual changes in OAHI over time predicted changes in neurocognitive and behavioral outcomes. This analysis identifies changes over time and between groups, while accounting for the large variability in OAHI and OAHI change within individuals (random effects). The model included time and group as fixed factors and OAHI as the covariate. Maternal education was also added as a fixed factor to control for the effects on group differences in neurocognitive and behavioral outcomes. Participant number was the random effect. Post hoc analysis was conducted on significant main and interaction effects with Bonferroni adjustments made for multiple comparisons (significance accepted at P ≤ 0.004). All data are presented as raw means ± SD.

RESULTS

Demographics

Based on the original diagnosis, 19 Control, 23 PS, 12 Mild OSA, and 8 MS OSA returned for the follow-up study. One control was excluded after starting to snore habitually. A further 4 refused the neurocognitive testing component of the study (2 PS, 1 Mild OSA and 1 MS OSA). The remaining 57 subjects were reclassified into 3 groups: Control (N = 18), Untreated (N = 27) and Treated (N = 12). A severe outlier on OAHI was identified in the Untreated group. Analysis with and without this outlier did not alter the direction or association between OAHI and outcome variables and thus was removed. Therefore, final analysis was conducted on N = 56. A subject was classified in the Treated group if they underwent AT (N = 9), tonsillectomy (N = 2), or had been prescribed nasal steroids (N = 1) as treatment for their SDB. The decision to treat was independent of the current study. Within the Treated group, 2 were initially diagnosed with PS, 5 with Mild OSA, and 5 with MS OSA. Retrospective analysis at Time 1 showed the number of arousals, OAHI and RDI were higher in the Treated group compared to the Untreated group. This was not surprising, considering the most severe children are more likely to undergo treatment. There were no differences in neurocognitive, academic or behavioral outcomes at Time 1 (means displayed in Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Results of nonparametric analysis for PSG respiratory variables

Table 4.

Results of linear mixed model analysis for main effects of group and time and interaction effect of time by OAHI for neurocognitive and behavioral variables

A comparison between the subjects who did and those who did not participate at Time 2 showed the returning subjects were slightly younger (9.0 ± 1.4 vs 9.8 ± 2.0 y; P < 0.05) and had significantly higher scores on Verbal IQ (VIQ) (105 ± 13 vs 98 ± 12; P < 0.001), Performance IQ (PIQ) (109 ± 16 vs 103 ± 15; P < 0.05) and Full-scale IQ (FSIQ) (108 ± 14 vs 100 ± 13; P < 0.01) at initial assessment. No differences were found in demographics, behavior, sleep, or respiratory parameters. A telephone interview with the parents who did not return revealed 22% of children with PS, 57% of children with mild OSA, and 83% of children with MS OSA underwent treatment (92% surgery) after the initial study. Of those who were treated, 92% were reported by parents to have improved. Parents reported 67% of those untreated also improved. Chi-squared analysis showed no significant difference in the proportion of children who received treatment in the PS, Mild or MS groups between those who returned and those who did not. There was also no difference in the proportion of those were deemed to have improved in the treated and untreated groups between the responders and non-responders.

The demographic profiles at Time 2 are displayed in Table 1. Maternal education was significantly higher in the control children, and was positively correlated with all neurocognitive outcomes (P < 0.05) and negatively correlated with all behavioral outcomes (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Demographic data at follow-up

Sleep, Respiration, and Arousal

Results for sleep diary and PSG outcomes are presented in Table 2. An expected age-related decrease was found in parent-reported habitual time in bed (TIB) and PSG TST. Overall, the percentage of NREM Stage 1 (%NREM1) significantly decreased and %NREM2 increased over time. Sleep efficiency reduced over time. A Group effect was seen in %NREM2, with post hoc testing revealing that %NREM2 was significantly higher in the Untreated group than the Treated group.

Table 2.

Results of repeated measures analysis for sleep variables

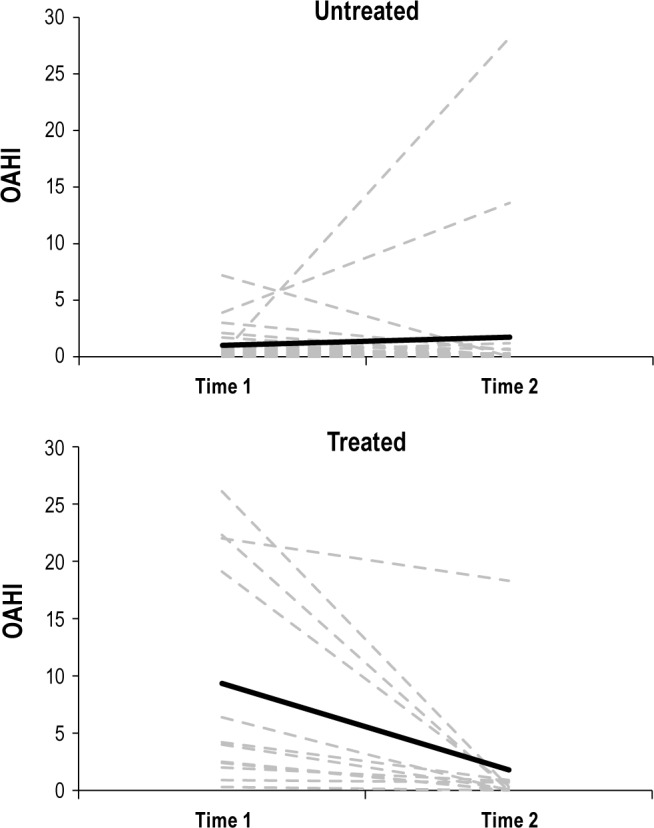

The changes over time in respiratory outcomes are presented in Table 3. Nonparametric analysis revealed the significant group differences in ArI, OAHI, and RDI at Time 1 were not evident at Time 2. A decrease in OAHI at Time 2 was seen in 100% of those who received treatment. A lower OAHI at Time 2 was also seen in 63% of the Untreated group. One subject initially categorized as a PS and one as Mild OSA became substantially worse over time, with increases in OAHI of 27 and 10 events/h, respectively. Neither of these subjects received treatment after the initial study. Individual OAHI data are presented in Figure 1 to demonstrate the large variability of change over time.

Figure 1.

Individual (dashed gray lines) and mean (solid black line) change in OAHI over time in the Untreated and Treated groups.

Neurocognition and Academic Ability

Mixed model results for fixed effects on neurocognitive outcomes are shown in Table 4. Main effects of Time were found for all IQ outcomes. Overall scores for VIQ and FSIQ were lower at Time 2 than Time 1 (VIQ; P < 0.003, FSIQ; P < 0.001). Differences between Time 1 and Time 2 in overall scores for PIQ did not reach significance after adjustment. A significant Group by OAHI interaction was observed in PIQ and FSIQ. The regression component of this analysis indicated a negative relationship between OAHI and PIQ, suggesting a decrease in OAHI between Time 1 and 2 was associated with an increase in PIQ (β = -0.89, P < 0.001). The change in OAHI did not predict a change in FSIQ (β = -0.62, P = 0.4).

A significant effect of maternal education was observed for VIQ (F1,5 = 5.6, P < 0.05), but not for PIQ or FSIQ.

Analyses for the academic measures revealed a significant main effect of Time for Reading (Table 4). Overall scores in reading ability were significantly higher at Time 2 than Time 1 (P < 0.003). No other main or interaction effects were found. Maternal education showed a significant effect on reading ability (F1,93 = 6.1, P < 0.05), but did not influence spelling or mathematical ability.

Behavior

Mean scores and mixed model main and interaction effects for CBCL and BRIEF are shown in Table 4.

There were significant main effects of Group for all CBCL outcomes. Post hoc analysis showed that parent ratings for Control children were significantly lower—indicating better behavior—than the Untreated and Treated groups for Internalizing (P < 0.001), Externalizing (P < 0.001), and Total Problems (P < 0.001). There was no difference in CBCL scores between Treated and Untreated groups. There were no significant main effects of Time or any Time by OAHI interactions for CBCL outcomes.

Mixed model analysis of the BRIEF results revealed a main effect of Time for Behavior Regulation Index and a main effect of Group for Global Executive Composite. Overall, mean BRI scores were lower at Time2 than Time 1 (P = 0.001), indicating better performance. Post hoc analysis revealed Control children scored significantly lower overall on Global Executive Composite than Untreated (P = 0.003) and Treated (P = 0.002). No interaction effects were found.

Maternal education did not prove to influence the relationship between the groups and behavioral outcomes as no signifi-cant effect of maternal education was found.

DISCUSSION

These results show that after four years, treatment of SDB is associated with improvements in some aspects of neurocognition but not academic ability or behavior. Specifically, children who had been treated for SDB showed an improvement in tasks associated with spatial visualization, visual-motor coordination, abstract thought, and nonverbal fluid reasoning (collectively categorized as Performance IQ), whereas children with SDB who were not treated showed no change in scores. Additionally, an improvement in OAHI was independently predictive of an improvement in Performance IQ. Contrary to previous short-term follow-up studies, treatment of SDB was not associated with improvements in behavior, with parents continuing to report significantly poorer behavior scores in both treated and untreated children compared to controls.

While the improvements in Performance IQ are consistent with our hypothesis, the lack of improvement in Verbal IQ, and indeed a worsening of performance, was unexpected. One possible explanation may be the different aspects of intelligence targeted by these domains. Verbal IQ is a measure of Crystalized Intelligence, an encompassing term describing the cognitive skills highly influenced by formal learning experiences. Performance IQ assesses Fluid Intelligence, which describes the cognitive skills reliant on one's ability to adapt to new situations. Fluid Intelligence is reflective of incidental learning.36 As research indicates that schooling has a larger effect on Verbal IQ than Performance IQ,37 it may be the behavioral problems reported in children with SDB result in an inability to attend to formal learning, particularly during crucial periods of development and maximal brain plasticity.38 This theory is supported by the lack of improvement in academic functioning in the current study. While basic assessments of academic ability may not be the most sensitive measure, the greatest saturation and thus development of spelling and single word reading occurs during the early school years. A seminal study by Gozal reported that first-grade children (approximately 5 years old) who underwent treatment for sleep-associated gas exchange abnormalities showed signifi-cant improvements in academic performance after 12 months compared to an untreated group.18 Our research shows that preschool children with SDB have deficits in behavior but not neurocognition.39 Behavior was not assessed in the Gozal study, but based on the consistent literature regarding behavioral problems in children with SDB, it can be suggested that early behavioral deficits may have resulted in a failure to optimize the early learning foundations such as those required for Verbal IQ and academic performance; however, the age of those children and their academic curriculum enabled a rebound effect. As the current cohort was older at Time 1 than the children in Gozal's study, it may be that the opportunity to improve in these basic academic measures was not available through formal schooling.

The fact that overall scores in Verbal IQ reduced over time is difficult to explain, however, has been observed before in Australian cohorts.40 As the normative data is based on American populations, this result may be reflective of cultural differences in educational curriculum and verbal development. It may also be that as adolescents, the participants were less motivated to perform at Time 2, which may have affected performance as the verbal knowledge components of the WASI require the greatest amount of sustained attention. However, if motivation were a factor, the reduction in scores would most likely be seen in the untreated group as well as the other two groups. Whatever the explanation, the reduction in Verbal IQ performance was not associated with treatment of SDB.

Another possible explanation for the specific association between SDB and Performance IQ involves sleep quality. Bruni et al.41 examined the association between brain activity during sleep and cognition in a cohort of healthy children aged 3-12 years. That study, using cyclic alternating pattern (CAP) analysis, which defines the periodic electroencephalogram activity in NREM sleep and reflects sleep maintenance and arousability, determined that nonverbal fluid reasoning was significantly associated with slow oscillating brain, or slow wave, activity. It has been reported that children with SDB have reduced slow wave stability when assessed using CAP,42 and we have recently shown that children with OSA have impaired SWA dissipation over the course of the night, suggesting they are not able to optimize the recovery function of sleep.43 Thus, it is possible that an improvement in OAHI could result in increased stability of brain activity during sleep, which may improve synaptic potentiation previously dampened by the arousal and hypoxic effects of SDB.44 Further studies are required to confirm this.

Unexpectedly, behavior did not significantly improve over time with parents of children with SDB reporting poorer behavior scores than controls, irrespective of treatment. This contradicts numerous previous studies13,15,16,45–47; however, in those studies, either the follow-up periods were short (≈6-12 months)13,15,16,46 or there was no control group for comparison.15,46 In addition, those studies did not include children with SDB who did not receive treatment. It may be that the previous studies are reporting an immediate parental impression related to the improvement in sleep following treatment rather than a global behavioral change. Alternatively, our finding may be the result of an initial referral bias. Parents of children with milder forms of SDB may be more likely to present their children for medical investigation if they have concurrent behavioral or psychosocial problems, than if snoring were the only symptom.48 Regardless, these results suggest that it is likely that in some cases, SDB is not the sole explanation for the behavioral symptoms and thus behavior will not change with improvement of SDB alone. Treatment strategies incorporating behavioral interventions in addition to traditional clinical practices may be required to reverse the behavioral deficits in these children.

Of note, 63% who were untreated, predominantly consisting of children with PS, showed some, albeit minimal, spontaneous improvement in OAHI. Aside from a small, but not statistically significant change in Internalizing Behavior, these children showed little change in behavior scores.

This study does have some limitations. The return rate presents some concern for the generalizability of the results, the small sample size reduces the ability to observe group differences in neurocognitive or behavioral changes over time, and while conducting assessments in the home provides ecological validity, the environment is not consistent. Also, information regarding additional tutoring or educational assistance between Time 1 and 2 was not obtained. It may be that the children most greatly affected by their OSA were provided with structured educational intervention, providing an alternate explanation for our results. However, if this were the case, it is likely that tutoring would have had a greater effect on Verbal IQ or academic performance. Finally, the natural history design of this study limits the interpretation of the results. A randomized treatment study would have been preferable; however, a design such as this raises serious ethical concerns when subjects have a condition with known adverse effects such as moderate-severe OSA. Although not ideal, the demographic similarities between the treated and non-treated groups, and between the responders and non-responders, provide us with confidence that the current results are likely to be a true reflection of the intervention.

In summary, contrary to shorter term follow-up studies, after a period of four years, improvement in SDB was associated with improvements in some aspects of neurocognition, but not behavior in school-aged children. These results suggest that longer periods following treatment of SDB are required to observe neurocognitive improvements, perhaps due to the slow recovery in cortical development. The lack of behavioral improvement over time may reflect a referral bias for children with milder forms of SDB. These results are highly informative as they provide valuable insights regarding the neurocognitive and behavioral sequelae of SDB which will inform clinicians in managing treatment of all severities of SDB.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. This research was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (Project number 384142), the Victorian Government's Operational Infrastructure Support Program and a generous scholarship donation from JE and HTE Maloney to support Anna Vlahandonis. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all the children and their parents who participated in this study and the staff of the Melbourne Children's Sleep Centre. We also thank Jillian Dorrian and Fiona Mensah for providing statistical advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Katz ES, D'Ambrosio CM. Pathophysiology of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:253–62. doi: 10.1513/pats.200707-111MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Church GD. The role of polysomnography in diagnosing and treating obstructive sleep apnea in pediatric patients. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2012;42:2–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blunden S, Lushington K, Kennedy D, Martin J, Dawson D. Behavior and neurocognitive performance in children aged 5-10 years who snore compared to controls. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2000;22:554–68. doi: 10.1076/1380-3395(200010)22:5;1-9;FT554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halbower AC, Degaonkar M, Barker PB, et al. Childhood obstructive sleep apnea associates with neuropsychological deficits and neuronal brain injury. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kennedy JD, Blunden S, Hirte C, et al. Reduced neurocognition in children who snore. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;37:330–7. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohler MJ, Lushington K, van den Heuvel CJ, Martin J, Pamula Y, Kennedy D. Adenotonsillectomy and neurocognitive deficits in children with sleep disordered breathing. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montgomery-Downs HE, Crabtree VM, Gozal D. Cognition, sleep and respiration in at-risk children treated for obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:336–42. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00082904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Brien LM, Mervis CB, Holbrook CR, et al. Neurobehavioral correlates of sleep-disordered breathing in children. J Sleep Res. 2004;13:165–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2004.00395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giordani B, Hodges EK, Guire KE, et al. Neuropsychological and behavioral functioning in children with and without obstructive sleep apnea referred for tonsillectomy. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2008;14:571–81. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708080776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Brien LM, Mervis CB, Holbrook CR, et al. Neurobehavioral implications of habitual snoring in children. Pediatrics. 2004;114:44–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Q, Sherrill DL, Goodwin JL, Quan SF. Association between sleep disordered breathing and behavior in school-aged children: The Tucson Children's Assessment of Sleep Apnea Study. Open Epidemiol J. 2008;1:1–9. doi: 10.2174/1874297100801010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nixon GM, Brouillette RT. Obstructive sleep apnea in children: do intranasal corticosteroids help? Am J Respir Med. 2002;1:159–66. doi: 10.1007/BF03256605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chervin RD, Ruzicka DL, Giordani BJ, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing, behavior, and cognition in children before and after adenotonsillectomy. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e769–78. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman BC, Hendeles-Amitai A, Kozminsky E, et al. Adenotonsillectomy improves neurocognitive function in children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 2003;26:999–1005. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.8.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galland BC, Dawes PJ, Tripp EG, Taylor BJ. Changes in behavior and attentional capacity after adenotonsillectomy. Pediatr Res. 2006;59:711–6. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000214992.69847.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giordani B, Hodges EK, Guire KE, et al. Changes in neuropsychological and behavioral functioning in children with and without obstructive sleep apnea following tonsillectomy. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2012;18:212–22. doi: 10.1017/S1355617711001743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hogan AM, Hill CM, Harrison D, Kirkham FJ. Cerebral blood flow velocity and cognition in children before and after adenotonsillectomy. Pediatrics. 2008;122:75–82. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gozal D. Sleep-disordered breathing and school performance in children. Pediatrics. 1998;102:616–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.3.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dillon JE, Blunden S, Ruzicka DL, et al. DSM-IV diagnoses and obstructive sleep apnea in children before and 1 year after adenotonsillectomy. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:1425–36. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31814b8eb2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poe GR, Walsh CM, Bjorness TE. Cognitive neuroscience of sleep. Prog Brain Res. 2010;185:1–19. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53702-7.00001-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bourke R, Anderson V, Yang JS, et al. Cognitive and academic functions are impaired in children with all severities of sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Med. 2011;12:489–96. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bourke RS, Anderson V, Yang JS, et al. Neurobehavioral function is impaired in children with all severities of sleep disordered breathing. Sleep Med. 2011;12:222–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonuck K, Freeman K, Chervin RD, Xu L. Sleep-disordered breathing in a population-based cohort: behavioral outcomes at 4 and 7 years. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e857–65. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walter LM, Nixon GM, Davey MJ, Anderson V, Walker AM, Horne RS. Autonomic dysfunction in children with sleep disordered breathing. Sleep Breath. 2013;17:605–13. doi: 10.1007/s11325-012-0727-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horne RS, Yang JS, Walter LM, et al. Elevated blood pressure during sleep and wake in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e85–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang JS, Nicholas CL, Nixon GM, et al. EEG spectral analysis of apnoeic events confirms visual scoring in childhood sleep disordered breathing. Sleep Breath. 2012;16:491–7. doi: 10.1007/s11325-011-0530-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang JS, Nicholas CL, Nixon GM, et al. Determining sleep quality in children with sleep disordered breathing: EEG spectral analysis compared with conventional polysomnography. Sleep. 2010;33:1165–72. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.9.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogden CL, Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts for the United States: improvements to the 1977 National Center for Health Statistics version. Pediatrics. 2002;109:45–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A manual of standardised terminology, techniques and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. Washington DC: U.S. Public Health Service; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 30.EEG arousals: scoring rules and examples: a preliminary report from the Sleep Disorders Atlas Task Force of the American Sleep Disorders Association. Sleep. 1992;15:173–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kahn A. The scoring of arousals in healthy term infants (between the ages of 1 and 6 months) J Sleep Res. 2005;14:37–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2004.00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. New York: The Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilkinson G. Wide Range Achievement Test: Administration manual. Wilmington, DE: Wide Range, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-based forms and profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth and Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gioia GA, Isquith PK, Guy SC, Kenworthy L. Behavior Rating of Executive Function. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cattell R. Theory of fluid and crystallized intelligence: A critical experiment. J Education Psych. 1963;54:1–22. doi: 10.1037/h0024654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cahan S, Cohen N. Age versus schooling effects on intelligence development. Child Dev. 1989;60:1239–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ringli M, Huber R. Developmental aspects of sleep slow waves: linking sleep, brain maturation and behavior. Prog Brain Res. 2011;193:63–82. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53839-0.00005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jackman AR, Biggs SN, Walter LM, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in preschool children is associated with behavioral, but not cognitive, impairments. Sleep Med. 2012;13:621–31. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grimwood K, Anderson P, Anderson V, Tan L, Nolan T. Twelve year outcomes following bacterial meningitis: further evidence for persisting effects. Arch Dis Child. 2000;83:111–6. doi: 10.1136/adc.83.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bruni O, Kohler M, Novelli L, et al. The role of NREM sleep instability in child cognitive performance. Sleep. 2012;35:649–56. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kheirandish-Gozal L, Miano S, Bruni O, et al. Reduced NREM sleep instability in children with sleep disordered breathing. Sleep. 2007;30:450–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.4.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Biggs SN, Walter LM, Nisbet LC, et al. Time course of EEG slow-wave activity in pre-school children with sleep disordered breathing: A possible mechanism for daytime deficits? Sleep Med. 2012;13:999–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neubauer AC, Fink A. Intelligence and neural efficiency. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:1004–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li HY, Huang YS, Chen NH, Fang TJ, Lee LA. Impact of adenotonsillectomy on behavior in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1142–7. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000217542.84013.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitchell RB, Kelly J. Long-term changes in behavior after adenotonsillectomy for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:374–8. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wei JL, Mayo MS, Smith HJ, Reese M, Weatherly RA. Improved behavior and sleep after adenotonsillectomy in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133:974–9. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.10.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beebe D, Wells C, Jeffries J, Chini B, Kalra M, Raouf A. Neuropsychological effects of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10:962–75. doi: 10.1017/s135561770410708x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]