Abstract

To overcome the limited sensitivity of phone cameras for mobile health (mHealth) fluorescent detection, we have previously developed a capillary array which enables a ~100× increase in detection sensitivity. However, for an effective detection platform, the optical configuration must allow for uniform measurement sensitivity between channels when using such a capillary array sensor. This is a challenge due to the parallax inherent in imaging long parallel capillary tubes with typical lens configurations.

To enable effective detection, we have developed an orthographic projection system in this work which forms parallel light projection images from the capillaries using an object-space telecentric lens configuration. This optical configuration results in a significantly higher degree of uniformity in measurement between channels, as well as a significantly reduced focal distance, which enables a more compact sensor.

A plano-convex lens (f = 150 mm) was shown to produce a uniform orthographic projection when properly combined with the phone camera’s built in lens (f = 4 mm), enabling measurements of long capillaries (125 mm) to be made from a distance of 160 mm. The number of parallel measurements which can be made is determined by the size of the secondary lens. Based on these results, a more compact configuration with shorter 32 mm capillaries and a plano-convex lens with a shorter focal length (f = 10 mm) was constructed.

This optical system was used to measure serial dilutions of fluorescein with a limit of detection (LOD) of 10 nM, similar to the LOD of a commercial plate reader. However, many plate readers based on standard 96 well plate requires sample volumes of 100 ul for measurement, while the capillary array requires a sample volume of less than 10 ul.

This optical configuration allows for a device to make use of the ~100× increase in fluorescent detection sensitivity produced by capillary amplification while maintaining a compact size and capability to analyze extremely small sample volumes. Such a device based on a phone or other optical mHealth technology will have the sensitivity of a conventional plate reader but have greater mHealth clinical utility, especially for telemedicine and for resource-poor settings and global health applications.

Keywords: mHealth, capillary, telecentric lens, orthographic projection, fluorescence, mobile and smart phone, camera

1. Introduction

In recent years mHealth (Mobile computing, medical sensors, and communications technologies for healthcare)1 has shown potential to address the need for medical diagnostics with clinical utilities. Many potential mHealth technologies have been developed, including a reader for lateral flow immuno-chromatographic assays 2, wide-field fluorescent microscopy 3, capillary array for immunodetection for Escherichia coli 4, lensfree microscopy 5, fluorescent imaging cytometry 6, microchip ELISA-based detection of ovarian cancer HE4 biomarker in urine 7, detection systems for melanoma or skin lesions 8–10, loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) genetic testing device 11, acoustic wave enhanced immunoassay 12, a colorimetric reader 13, phone-assisted microarray reader for mutation detection 14, and mobile phones cameras for DNA detection 15. Another application for mHealth is medical diagnostics in low and middle-income countries. Most of the population in these countries lacks access to current medical diagnostics. The challenge and the need for these countries is to develop simple, low-cost diagnostics for resource-poor settings with minimal medical infrastructure 16–18.

Many mHealth technologies are based on optical detection utilizing the camera in a mobile device, such as a phone. However, the limiting factor for many of these technologies is the low sensitivity of the CMOS camera native to the mobile devices, which is too low to be useful for many optical modalities, such as low intensity fluorescent signal detection.

For clinical use, these technologies have to be comparable in terms of sensitivity and functionality to current commercial technologies which often use state-of-the-art ultra-sensitive detectors (photomultipliers, avalanche photodiodes, cooled CCD etc) which are too expensive and not practical for low cost detectors. Developing sensitive optical technologies for mHealth and global health under the constraints (the use of low sensitivity mobile device, low cost, need for high sensitivity, etc.) in these settings is a great challenge, and several approaches have been developed to try and overcome this challenge.

We recently developed a computational approach using “image stacking” to improve sensitivity for fluorescent detection 19 by acquiring images using a webcam (which utilize CMOS sensors similar to typical camera phones) in video mode to capture many individual frames and combine them with an image stacking algorithm to average the values of each pixel so that the random noise which is present can be significantly reduced. This approach increased the limit of detection by 10 fold, and enabled the detection of very weak signals that would normally be masked by noise without the use of image stacking.

In addition to computational image enhancement through image stacking, optical amplification of signals can also increase sensitivity. Previously, capillary tubes have been used in medical diagnostic for both assay fluid handling and waveguide illumination 20. We developed a capillary array which enabled a ~100× increase in detection sensitivity. These arrays are three dimensional detection system, with X columns and Y rows of capillaries in two dimensions and the waveguide light propagation via the capillary’s wall providing a third Z dimension for illumination along the axes of the capillaries.

One issue with the capillary array is the uniformity of the fluorescent signal measurements from the 3D capillary array. The optical configuration for detecting such 3D capillary array sensors is a challenge which requires a system capable of uniformly detecting optical signals through long parallel capillaries tubes distributed in a large space. To image the 3D capillary array, orthographic projection, which is capable of representing three dimensional objects in two dimension, can be applied. Orthographic projection is a form of parallel projection of 3D objects with all the projection lines orthogonal to the projection plane, resulting in every plane of the captured image retaining straight lines and parallelism (an affine transformation) on the sensor. We describe here an orthographic projection sensor capable of uniform fluorescent measurements from capillary arrays.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Materials and reagents

The 16-channel capillary arrays used for analysis were fabricated with the glass capillaries (Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA) held in a square array by black poly(methyl-methacrylate) (PMMA) (Piedmont Plastic, Inc. Beltsville, MD). The fluorescence measurements were made using fluorescein (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC) diluted in water as a standard.

2.2 mHealth fluorescence detector

The main components of mHealth fluorescence detector are: (1) LED excitation source described in previous work21 with illumination spectra 450–650 nm (red 610–650 nm, green 510–550 nm, and blue 440–495 nm). (2) Excitation and emission filters for fluorescein: 20 nm passband filter with 486 nm center wavelength for excitation, and a 50 nm passband filter with center wavelength of 535 nm for emission (both from Chroma Technology Corp., Rockingham, VT). (3) Samsung Galaxy SII cellphone (Samsung Electronics Co.) with a built-in lens with a focal ratio of f/2.6 and a 4 mm focal length. The lenses used were a large plano-convex lens (45 mm diameter, 150 mm focal length) for 125 mm capillaries configuration and a smaller lens (2 cm diameter, 1 cm focal length) for shorter 32 mm capillaries.

2.3 Fabrication of 36-channel fluidics

To orient all the capillary channels towards the camera image sensor simultaneously, two four-by-four arrays of holes in 3.2 mm thick plates of black acrylic were fabricated which hold the capillaries in a parallel configuration. The length of the capillaries used is 32 mm with outer diameter of 0.8 mm, the inner diameter of 0.65 mm and with glass thickness of around 50 microns.

2.4 Image processing

Images were captured with the exposure time for the cell phone camera set to its maximum of 1/15 s and the camera gain set to its maximum of 800 ISO. The images are in 8-bit color JPEG format. Each color image is essentially three different monochrome images, each one representing a color channel (red, green and blue) and each pixel of each image having a value between 0 and 255. Because the signal of interest for fluorescein is in the green spectrum, the green channel alone is analyzed and the red and blue channels are discarded.

To reduce background noise in the final image and improve the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), an average dark frame was subtracted from each image to be analyzed. A dark frame is an image with identical exposure time and gain settings as the original image, but taken with no light reaching the camera sensor (i.e. with a lens cap in place). When several of these dark frames are averaged together, the resulting image represents the average background noise generated by the camera sensor. This averaging was done in ImageJ using many (>30) dark frames with the mean value for each pixel calculated and combined to form the final dark frame. The green channel was extracted from this mean dark frame image and subtracted from the green channel of the corresponding original image containing the signal of interest. This process has been described in greater depth in previous work 19, 22. Image signals were quantitated using ImageJ software developed and distributed freely by NIH (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/download.html).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Orthographic Projection Fluorescent Sensor

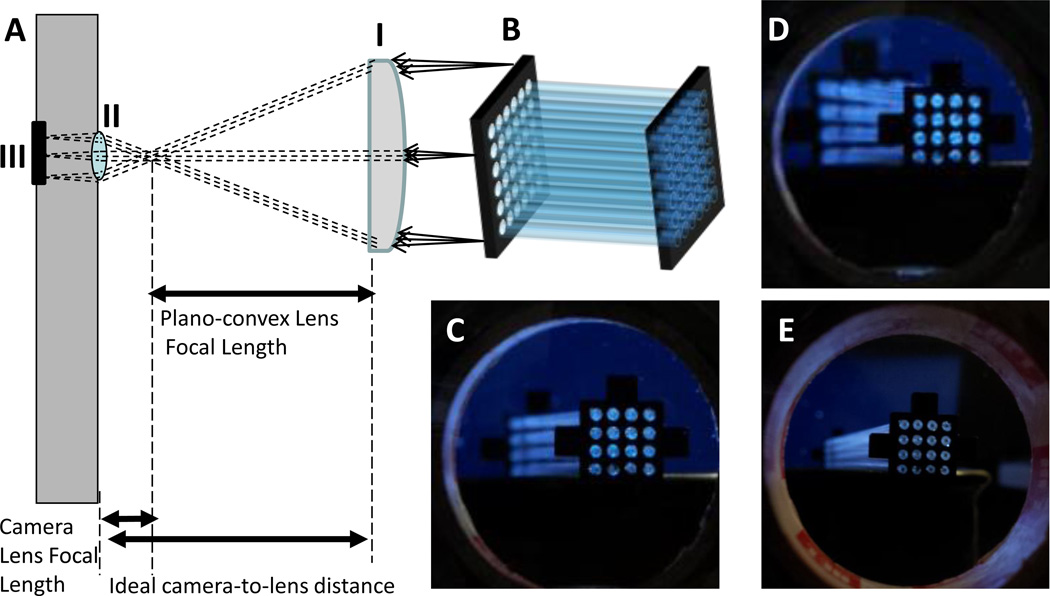

To image the 3 dimensional capillary array, orthographic projection optics using a telecentric lens to represent the three dimensional array in two dimensions was used. The basic optical configuration of the object-space telecentric optics is shown schematically in figure 1A, with the plano-convex lens (figure 1A-I) and the principal rays imaged by the lens of the phone camera (figure 1A-II) focusing the image onto the camera’s CMOS sensor (figure 1A-III). The capillary array (figure 1B) is imaged with the added plano-convex lens (4.5 cm diameter, 15 cm focal length) in three different positions. As shown in figure 1C, at the ideal camera-to-lens distance where the focal points of the camera phone lens and the secondary lens are aligned, the object-space telecentric condition is achieved and a parallel projection of the 3D capillary array is seen (figure 1B). All of the projection lines (i.e. light rays imaged by the telecentric lens) from the 3D capillary array are orthogonal to the projection plane, resulting in every plane of the captured image retaining straight lines and parallelism (i.e. an affine transformation) on the sensor. In figure 1D, the image is taken with the secondary lens at a distance too far from the camera, and in figure 1E the distance is too close. Both configurations D and E result in images where the capillaries seem to converge or diverge towards the viewer. In a fluorescence measurement scenario, this results in the center capillaries appearing brighter than the peripheral capillaries. At the ideal camera-to-lens distance, the focal points of the camera lens (figure 1A-I) and the secondary lens (figure 1A-II) are aligned. This is the simplest possible object-space telecentric setup. The term “object-space telecentric” indicates that an object at any distance from the lens will appear the same size in the resultant image. Another telecentric configuration is “image-space,” where for a fixed object distance, moving the image plane does not affect the magnification of the image.

Figure 1. The effect of orthographic projection configuration on the imaging of capillary array.

To demonstrate the effect of orthographic projection optics, a sixteen tubes capillary array (12.5 cm in length) imaged with a typical cell phone camera through a plano-convex lens (4.5 cm diameter, 15 cm focal length). (A) A schematic of the object-space telecentric optics with (i) the plano-convex secondary lens and the principal rays imaged by the lens of (ii) the phone camera which focuses the image onto (iii) the camera CMOS image sensor. (B) A schematic of the capillary array. The capillary array was imaged at three different camera-to-lens distances: C = 14.5 cm, D = 30cm and E = 5 cm. The object-space telecentric condition is satisfied at (C) the ideal camera-to-lens distance so that all capillaries of the array appear parallel. (D) Too far of a camera-to-lens distance, and (E) position at too close of a camera-to-lens distance. Configurations D and E both result in uneven images of the capillary array with the center capillaries appearing brighter than those on the edges during fluorescence measurement.

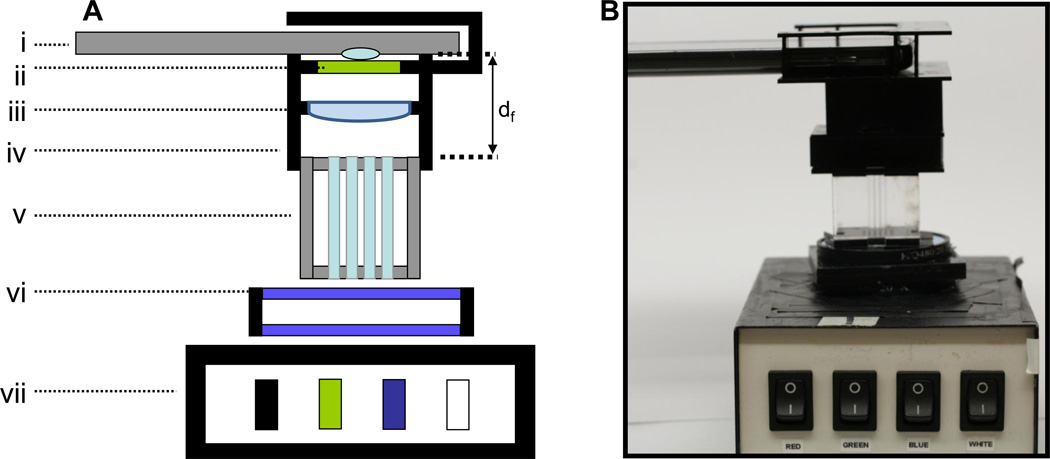

The main elements of the orthographic projection fluorescent sensor are shown in figure 2: a schematic of the camera phone fluorometer with the telecentric lens configuration (figure 2A), and a photo of the actual device (figure 2B). The main components are: (i) camera phone, (ii) emission filter, (iii) secondary lens, (iv) alignment fixture, (v) capillary tube array, (vi) two spaced excitation filters, and (vii) multi-wavelength LED light box. The system also includes a computer to acquire and analyze images. In figure 2A, df is the distance between the capillaries and the camera lens which can be minimized by proper secondary lens selection. In the configuration shown, df is 32 mm to achieve both focus and uniform capillary illumination, while without the secondary lens the minimum df is 65 mm to achieve focus, and approximately 140 mm to achieve uniform capillary images.

Figure 2. Orthographic projection fluorescent sensor for mHealth.

(A) A schematic of the orthographic projection fluorescent sensor and (B) a photograph of the device. Constituent parts are: (i) camera phone, (ii) emission filter, (iii) secondary lens, (iv) alignment fixture, (v) capillary tube array, (vi) two spaced excitation filters, and (vii) multi-wavelength LED light box. In (A), df is the distance between the capillaries and the camera lens.

In the configuration shown in figure 2, two excitation filters (figure 2A-vi) are used. This is because the excitation filters used are interference filters, and the light source is diffuse. The wavelength of light allowed to pass through this type of filter is highly dependent on the angle at which the light passes through the filter. In order to ensure the narrow excitation bandwidth necessary for the emission filter to block the excitation light, something must be done to constrain the angle of light passing through the filters. One very simple method to effectively constrain this angle is to use two filters separated by some distance. The greater this distance, the more constrained the angle of light will be (in this case a distance of approximately 10mm was found to be suitable). A more ideal solution is to use a light source which is collimated well enough that all of its light falls within the range of angles that allow a single filter to be used. This corresponds to an angular divergence of approximately twenty degrees. For measuring particles emitting at different wavelengths, the illumination spectra of the LED is 450–650 nm and both excitation and emission filters are interchangeable.

The waveguide capillary array shown schematically in figure 2A-V (actual photo shown in figure 1B) was used for fluorescence amplification. The array of capillaries is held together on the top and the bottom by two acrylic holders with holes which the capillaries are inserted through. The capillaries are illuminated by the multi-wave length LED illuminator21 (figure 2AVII) capable of exciting multiple fluorophores over a wide excitation spectrum of 450–650 nm (red 610–650 nm, green 512–550 nm, and blue 450–465 nm). For the fluorescence detection used in this work, light is emitted and passed through the excitation filter (figure 2A-vi), carried through the capillaries (figure 2A-v), collected by the secondary lens (figure 2A-iii) which forms a parallel projection of the capillary array through the emission filter (figure 2A-ii), and is then finally captured by the camera (figure 2A-i). This optical configuration (figure 2A) is very compact (with focal length distance 32 mm) compared to the standard configuration without the plano-convex lens that has an effective focal length of 65 mm and a minimum useful distance of 140 mm for uniform capillary imaging.

3.2 The light distribution using orthographic projection optics

To demonstrate the capability of the orthographic projection fluorescent sensor, fluorescein (a common dye used in many biological assays) was used as a model fluorescence media. In the capillary array, the excitation light-wave energy propagating through the capillary walls can interact directly and excite the fluorescein molecules (via evanescent waves) which emit light. The emitted photons were then detected at the end of the capillary by an imaging detector.

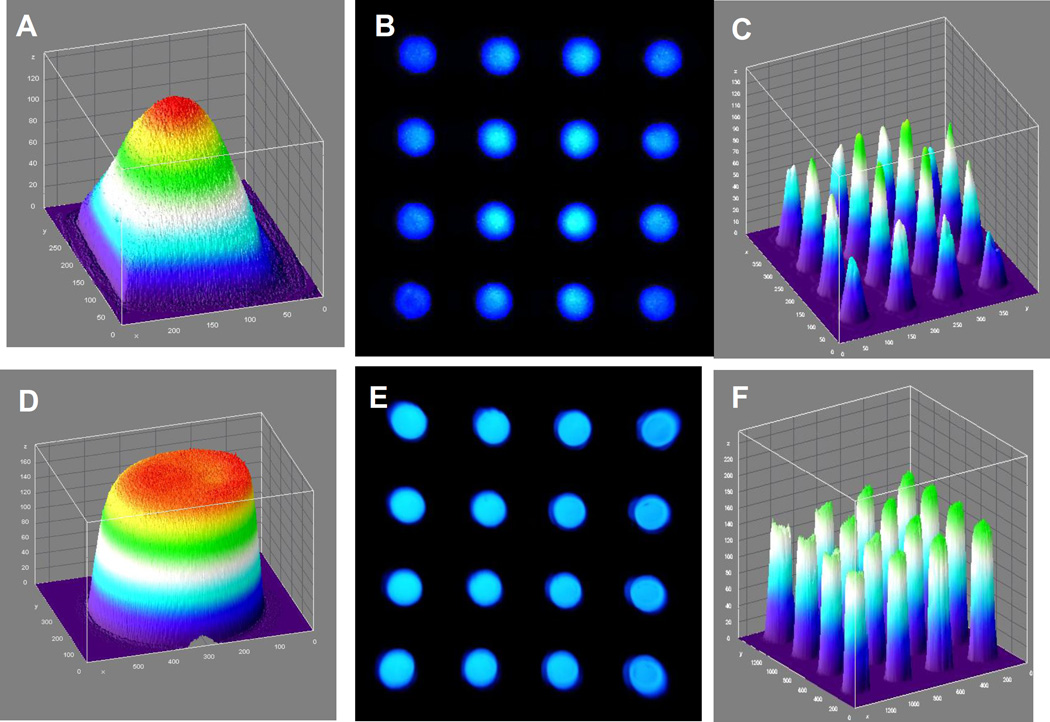

The fluorescein example has a peak excitation wavelength of 494 nm and an emission maximum of 521 nm. A 3D graphical representation of the 2D light intensity distribution without the telecentric lens is shown in figure 3A. It can be seen that the light is not uniformly distributed across the space being imaged, especially toward the edges of the imaging field. The comparable distribution of the light obtained using the telecentric lens (figure 3D) is much more uniform. When imaging a 4×4 capillary array with standard lens configuration (figure 3B), there is significantly uneven florescence signal from the capillaries, as shown graphically in figure 3C, especially at the edges of the capillary array. In contrast the fluorescent emission is more uniform using the orthographic projection configuration (figure 3E), resulting in a much reduced edge effect for the fluorescent signal (figure 3F). These results clearly demonstrate the advantage of using orthographic projection optics in this case.

Figure 3. The light distribution using orthographic projection optics.

(A) A 3D visualization of the planar illumination source is shown as seen with the single lens system. (B) The light field seen by the single lens system when looking at an array of 16 capillary tubes, with (C) corresponding 3D visualization. (D, E, F) Corresponding results for the telecentric lens system are also shown, demonstrating a significantly more uniform illumination field.

3.3 The sensitivity of Orthographic Projection Fluorescent Sensor is similar to the sensitivity of modern plate reader

The main limiting factor of many mHealth optical detectors is the low sensitivity of the CMOS camera native to the mobile devices, which is too low to be useful for many optical modalities, such as low fluorescent signal detection. To be of clinical utility, mHealth technologies must have comparable or better sensitivity to current detection technologies.

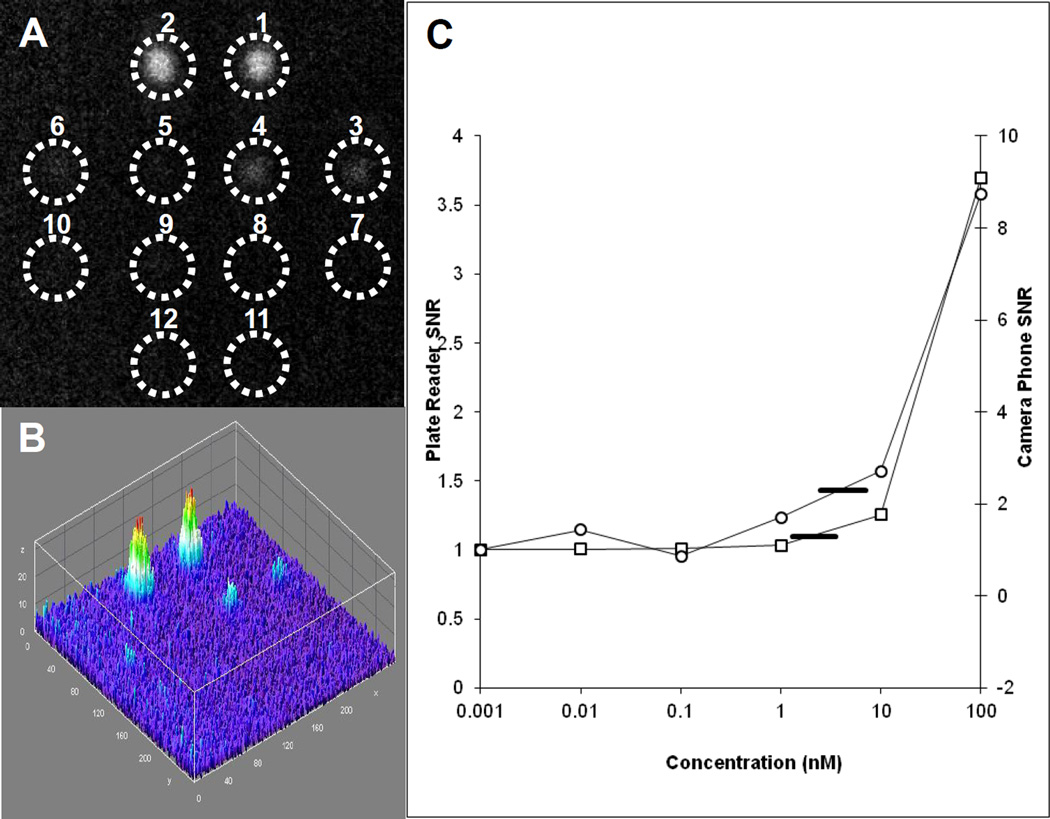

To analyze the sensitivity of this phone based orthographic projection fluorescent sensor we compared its sensitivity to the sensitivity of a modern of state of the art plate reader. A twelve capillary array was loaded with serial dilutions of six concentrations of fluorescein in duplicate pairs: 100 nM, 10 nM, 1 nM, 0.1 nM, 0.01 nM, and 0 nM (water). The array was illuminated by an LED illuminator with a blue excitation filter, and was measured with a green emission filter. The signals of the wells were detected by the phone camera with the exposure time for the cell phone camera set to its maximum (1/15 s) and the camera gain was set to its maximum (800 ISO) (Figure 4 A). The corresponding ImageJ 3D image is shown in Figure 4B). The same serial dilutions of six concentrations of fluorescein were analyzed by a Tecan Infinite m1000 plate reader. The two curves of the camera and plate reader are very similar (figure 4C) with a difference in scale attributable to different system gains. After multiple (N>10) measurements, the same limit of detection (10 nM) was calculated for each system. LOD was calculated as the mean signal from water plus three times the standard deviation of those measurements (marked as a horizontal line in figure 4C). Concentrations of fluorescein which yielded a mean signal that was above this limit were considered to be detected. While the LOD for both systems was found to be the same, the minimal volume for reliable measurements of many plate reader which are based on standard 96 well plate is 100 ul while the volume of the capillary is 8.5 ul, so the plate reader requires ~10× the volume of sample for a similar LOD.

Figure 4. The sensitivity of Orthographic Projection Fluorescent Sensor compared to the sensitivity of plate reader.

A twelve capillary array was loaded with fluorescein. (A) A single fluorescence image from camera phone is shown with (B) corresponding 3D intensity plot. The six concentrations of fluorescein were measured in duplicate pairs: capillaries 1 and 2, 100 nM; capillaries 3 and 4, 10 nM; capillaries 5 and 6, 1 nM; capillaries 7 and 8, 0.1 nM, capillaries 9 and 10, 0.01 nM, and capillaries 11 and 12, 0nM (water). (C) Results for the camera phone are plotted as open circles, along with results from a commercial fluorescence plate reader plotted as open squares. Limit of detection for both systems were 10nM for the concentrations measured (LOD marked as a horizontal black line for both sets of data).

4. Conclusions

In recent years growing number of mHealth technologies were developed for diverse biomedical applications 2–15. While many such applications rely on optical detection, the limiting factor for the clinical utility of such technologies is the low sensitivity of the mobile device camera. While such a limitation can be overcome by increasing the sensitivity of optical detection through the use of a capillary waveguide array, uniform imaging of such an array is challenging because of the 3D configuration of the array.

In our orthographic projection detection system, the parallel light projection images from the capillaries are formed by an object-space telecentric lens to remove the effects of parallax on measured light intensity. In this configuration, the telecentric lens focuses only those rays which are perpendicular to the image plane. When imaging 3D objects (such the capillary array), the telecentric lens removes the perspective or parallax error that makes closer objects appear to be larger than objects farther from the lens, and thus enable uniform and undistorted imaging compared to conventional lenses.

The low cost orthographic projection fluorescent sensor described here with sensitivity similar to a plate reader and ability to analyze smaller sample volumes has potential use in mHealth and global health for many of the clinical florescent assays, thereby improving the access for medical diagnostics in global health settings.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the FDA's Center for Devices and Radiological Health, Division of Biology and the National Cancer Institute. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not represent those of the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Istepanian R, Jovanov E, Zhang YT. IEEE transactions on information technology in biomedicine : a publication of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. 2004;8:405–414. doi: 10.1109/titb.2004.840019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mudanyali O, Dimitrov S, Sikora U, Padmanabhan S, Navruz I, Ozcan A. Lab on a chip. 2012;12:2678–2686. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40235a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu H, Yaglidere O, Su TW, Tseng D, Ozcan A. Conference proceedings : … Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Conference; IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; 2011. pp. 6801–6804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu H, Sikora U, Ozcan A. Analyst. 2012;137:2541–2544. doi: 10.1039/c2an35071h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tseng D, Mudanyali O, Oztoprak C, Isikman SO, Sencan I, Yaglidere O, Ozcan A. Lab on a chip. 2010;10:1787–1792. doi: 10.1039/c003477k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu H, Mavandadi S, Coskun AF, Yaglidere O, Ozcan A. Anal Chem. 2011;83:6641–6647. doi: 10.1021/ac201587a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang S, Zhao X, Khimji I, Akbas R, Qiu W, Edwards D, Cramer DW, Ye B, Demirci U. Lab on a chip. 2011;11:3411–3418. doi: 10.1039/c1lc20479c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosado L, Castro R, Ferreira L, Ferreira M. Studies in health technology and informatics. 2012;177:242–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wadhawan T, Situ N, Rui H, Lancaster K, Yuan X, Zouridakis G. Conference proceedings : … Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Conference; IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; 2011. pp. 3180–3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyce Z, Gilmore S, Xu C, Soyer HP. Dermatology. 2011;223:244–250. doi: 10.1159/000333363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stedtfeld RD, Tourlousse DM, Seyrig G, Stedtfeld TM, Kronlein M, Price S, Ahmad F, Gulari E, Tiedje JM, Hashsham SA. Lab on a chip. 2012;12:1454–1462. doi: 10.1039/c2lc21226a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bourquin Y, Reboud J, Wilson R, Zhang Y, Cooper JM. Lab on a chip. 2011;11:2725–2730. doi: 10.1039/c1lc20320g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee DS, Jeon BG, Ihm C, Park JK, Jung MY. Lab on a chip. 2011;11:120–126. doi: 10.1039/c0lc00209g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang G, Li C, Lu Y, Hu H, Xiang G, Liang Z, Liao P, Dai P, Xing W, Cheng J. Biosens Bioelectron. 2011;26:4708–4714. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2011.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee D, Chou WP, Yeh SH, Chen PJ, Chen PH. Biosens Bioelectron. 2011;26:4349–4354. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2011.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hay Burgess DC, Wasserman J, Dahl CA. Nature. 2006;444(Suppl 1):1–2. doi: 10.1038/nature05440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Urdea M, Penny LA, Olmsted SS, Giovanni MY, Kaspar P, Shepherd A, Wilson P, Dahl CA, Buchsbaum S, Moeller G, Hay Burgess DC. Nature. 2006;444(Suppl 1):73–79. doi: 10.1038/nature05448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yager P, Domingo GJ, Gerdes J. Annual review of biomedical engineering. 2008;10:107–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.10.061807.160524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balsam J, Bruck HA, Kostov Y, Rasooly A. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 2012;171–172:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weigl BH, Holobar A, Trettnak W, Klimant I, Kraus H, O'Leary P, Wolfbeis OS. Journal of biotechnology. 1994;32:127–138. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(94)90175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun S, Francis J, Sapsford KE, Kostov Y, Rasooly A. Sensors and actuators. B, Chemical. 2010;146:297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balsam J, Ossandon M, Bruck HA, Rasooly A. Analyst. 2012;137:5011–5017. doi: 10.1039/c2an35729a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]