Abstract

Mature cystic teratomas are benign ovarian neoplasms which account for around 95% of all ovarian germ cell tumours and contain tissues derived from two or three embryonic germ layers. These tumours are frequently diagnosed in women of reproductive age group and can result in fetomaternal distress if concurrent pregnancy occurs. The authors describe a case of successful natural pregnancy in a 30-year-old woman with coexisting mature cystic teratoma of ovary that culminated in viable childbirth at term. Subsequent histopathological examination of the tumour revealed a mature teratoma composed predominantly of ectodermal elements along with retinal tissues—a rare finding that prompted this case report.

Background

Mature cystic teratomas (MCT) account for 27–44% of all ovarian neoplasms and are the most common germ cell tumours of the ovary.1 They contain mature adult-type tissues derived from two or three embryonic germ layers, namely ectoderm (eg, skin with appendages and neural elements), mesoderm (eg, adipose tissue, muscle) and endoderm (eg, respiratory and intestinal epithelium).1 We describe the case of a 30-year-old Indian woman presenting with full-term pregnancy and a concurrent right ovarian mature teratoma comprising ectodermal and mesodermal elements along with retinal tissues—a rare component seldom seen in MCTs. Our case is an interesting one due to two reasons: first, the presentation of MCT with full-term pregnancy and resulting in viable baby; second, the presence of unusual components in the form of retinal tissue.

Case presentation

A 30-year-old primigravida presented at the obstetrics outpatient department with 9 months amenorrhoea and vague pain in the right infraumbilical region. She came from a rural background with poor socioeconomic status. There was no history of any antenatal check-up. Clinical examination revealed a gravid uterus corresponding to 38 weeks of gestational age. Additionally, a mass was palpable separately in the right adnexal region measuring approximately 8×8 cm. A provisional diagnosis of primigravida with 38 weeks pregnancy and right adnexal mass was made and the patient was admitted.

Investigations

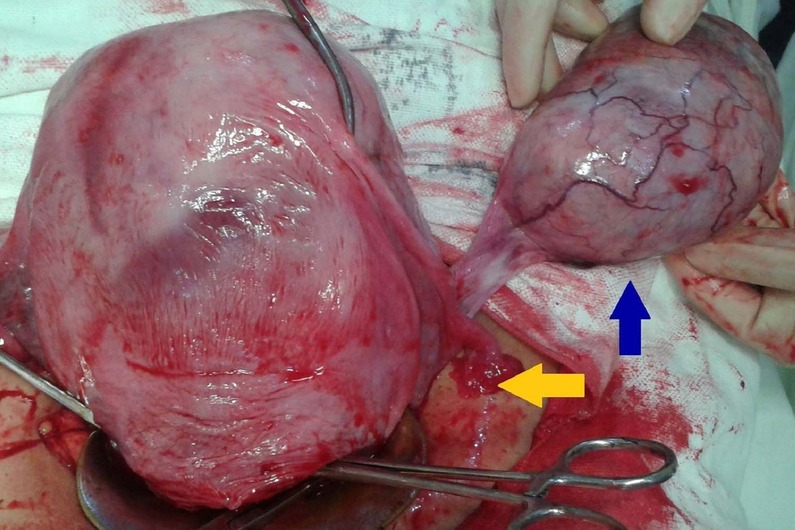

Ultrasonography of the abdomen, performed subsequently, confirmed intrauterine pregnancy with single live fetus along with a cystic echogenic shadow (9×8.5 cm), posterior to cornu, arising from the right ovary. No abnormality was detected in the left ovary and adnexa. In an attempt to deliver a viable baby, laparotomy with lower segment caesarean section was performed. A live male baby was delivered. Peroperatively, a right-sided cystic ovarian mass with intact capsule was also noted (figure 1). No retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy was detected and omentum was unremarkable. Right ovarian cystectomy was performed simultaneously.

Figure 1.

Intraoperative photograph of gravid uterus (yellow arrow) alongside the ovarian tumour (blue arrow) having glistening intact capsule and tortuous vessels on the surface.

On pathological examination, the ovarian mass grossly measured 9×9×4.5 cm and had a greyish-brown smooth outer surface with intact capsule. Cut section showed a thin-walled unilocular cyst filled with yellowish sebaceous material and tufts of hairs (figure 2). Microscopically, the cyst was lined by keratinised stratified squamous epithelium with hair follicles and sebaceous glands. Mature glial tissue with cell bodies of neurons was also observed. Adjacent to this neural component was an area containing melanin loaded cells resembling the retinal pigment epithelium. Mesodermal elements included smooth muscles and adipose tissue (figure 3). In spite of extensive sampling, no endodermal derivatives or immature components were detected.

Figure 2.

Gross picture showing opened up thin-walled unilocular cyst (left) and its content—yellowish sebaceous material and tufts of hairs (right).

Figure 3.

H&E stained sections from the tumour showing (A) Cyst wall lined by keratinised stratified squamous epithelium with hair follicles, sebaceous glands, adipose tissue and smooth muscle bundles (×40). (B) Melanin loaded elongated cells resembling retinal pigment epithelium merging with glial tissue and blood vessels (×40). (C) Higher magnification of the retinal anlage and pigment epithelium (×100). (D) Neuroglial tissue with cell bodies of neurons (×100).

Outcome and follow-up

The postoperative course remained uneventful. The newborn and his mother were discharged on the fifth postoperative day in a healthy condition. The mother continues to attend follow-up and at 3 months since the delivery, is currently doing well.

Discussion

Teratomas are germ cell tumours composed of various cell types representing different embryonic germ layers. They range from benign cystic lesions (mature) to those that are solid and malignant (immature). The term ‘dermoid cyst’, commonly used as a synonym for mature cystic teratoma, is appropriate only for those examples composed exclusively of epidermal elements with adnexal structures.1 2

MCT accounts for 95% of all ovarian germ cell tumours. Most of the cases are diagnosed during the reproductive period with mean age of presentation at 32 years, a finding consistent with our case. In 10–15% cases, these tumours are bilateral.1 2 Majority of MCTs have 46, XX chromosomal constitution and arise parthenogenetically from pleuripotent postmeiotic ovarian germ cells. The presence of Barr bodies (nuclear sex chromatin) in the tumour cells bear testimony to the above fact.3

Although patients may complain of non-specific symptoms like abdominal distension and pain, the larger proportion of cases remain asymptomatic and are only discovered incidentally either during pelvic examination or surgery for other indications.1 4 In rare instances, MCTs may become overtly symptomatic due to excessive ectopic hormone production or the onset of complications.5 6 The latter includes torsion, rupture, infection, malignant transformation and immune haemolytic anaemia. During pregnancy, the ovaries rise out of the pelvis due to stretching by the gravid uterus and this displacement coupled with increased mobility predispose to torsion.6 This probably explains the reason for infraumbilical pain that our patient presented with.

MCTs can frequently arise in combination with other ovarian neoplasms; such association is the commonest with mucinous cystadenoma (in around 40% cases). Also multiple MCTs can arise in the same ovary simultaneously. These points deserve the pathologists’ as well as the clinicians’ attention.2

Histopathologically, one may find a variety of mature tissues in MCTs. The presence of ectodermal, mesodermal and endodermal elements is noted in approximately 100%, 93% and 71% cases of ovarian MCTs, respectively.7 Keratinised stratified squamous epithelium with adnexa (hair follicle, sebaceous and sweat glands) almost universally line the cyst wall. Other commonly observed tissues include adipose tissue, smooth muscles, cartilage, cerebrum, peripheral nerves and respiratory epithelium.1 4 7 Tissues that are rarely present (less than 5% cases) in MCTs are the retina, kidney, liver, cardiac muscle, striated muscle and prostate.7

Several authors have reported the presence of retinal tissue in ovarian MCT and in almost all of them this has been an incidental finding.1 4 7 8 However, no concrete evidence is available on whether the presence of this element is associated with any prognostic or therapeutic significance and this remains a potential area for the future research. Mercur et al,9 who observed retinal tissue in a developing eye in immature teratoma of the ovary advocated extensive tumour sampling whenever such uncommon elements are found in MCT, to rule out the presence of any immature component as it adversely affects the prognosis and changes the approach to treatment.9

MCTs are extremely slow growing tumours with an average growth rate of 1.8 mm per year. This fact has prompted investigators to advocate non-surgical management of smaller tumours (<6 cm in size) when diagnosed in pregnancy.10 Larger tumours need to be resected, either in the second trimester or alongside caesarean section or in early puerperium. However, if complications set in, urgent surgical intervention may be required irrespective of the period of gestation.2

Learning points.

Mature cystic teratomas are benign ovarian neoplasms which frequently occur in women of reproductive age group.

They can occur concurrently with pregnancy and when they do, may result in fetomaternal distress, if not managed on time.

These tumours have the potential to arise multifocally as well in combination with other ovarian neoplasms.

Pathologists should be aware of the presence of rare elements in mature teratomas.

Examination of multiple tissue sections is advocated in all cases of teratoma to exclude the presence of any immature component since this affects the prognosis adversely.

Footnotes

Contributors: NK was instrumental in making the histopathological diagnosis and manuscript editing. PS performed the literature search and manuscript preparation. SH and FZ evaluated and managed the case and provided the clinical data.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Nogales F, Talerman A, Kubik-Huch RA, et al. Germ cell tumours. In: Tavassoli FA, Deville P. World Health Organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the breast and female genital organs. Lyon: IARC Press, 2003:168–71 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Padubidri VG, Daftary SN. Disorders of the ovary and benign tumours. In: Padubidri VG, Daftary SN, eds. Shaw's textbook of gynaecology. 14th edn New Delhi: Elsevier, 2008:336–48 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahl N, Gustavson KH, Rune C, et al. Benign ovarian teratomas: an analysis of their cellular origin. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1990;46:115–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayhan A, Bukulmez O, Genc C, et al. Mature cystic teratomas of the ovary: case series from one institution over 34 years. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2000;88:153–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pothula V, Matseoane S, Godfrey H. Gonadotropin-producing benign cystic teratoma simulating a ruptured ectopic pregnancy. J Natl Med Assoc 1994;86:221–2 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pantoja E, Noy MA, Axtmayer RW, et al. Ovarian dermoids and their complications. Comprehensive historical review. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1975;30:1–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russel P, Painter DM. The pathological assessment of ovarian neoplasms V: the germ cell tumours. Pathology 1982;14:47–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McManis JC, Angevine JM. Retinal tissue in benign cystic ovarian teratoma. Am J Clin Pathol 1969;51:508–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mercur L, Farkas TG, Anker PM, et al. Developing eye in an ovarian teratoma. Arch Ophthalmol 1976;94:597–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caspi B, Levi R, Appelman Z, et al. Conservative management of ovarian cystic teratoma during pregnancy and labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;182:503–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]