Abstract

Background

The EPSPS, EC 2.5.1.19 (5-enolpyruvylshikimate −3-phosphate synthase) is considered as one of the crucial enzyme in the shikimate pathway for the biosynthesis of essential aromatic amino acids and secondary metabolites in plants, fungi along with microorganisms. It is also proved as a specific target of broad spectrum herbicide glyphosate.

Results

On the basis of structure analysis, this EPSPS gene family comprises the presence of EPSPS I domain, which is highly conserved among different plant species. Here, we followed an in-silico approach to identify and characterize the EPSPS genes from different plant species. On the basis of their phylogeny and sequence conservation, we divided them in to two groups. Moreover, the interacting partners and co-expression data of the gene revealed the importance of this gene family in maintaining cellular and metabolic functions in the cell. The present study also highlighted the highest accumulation of EPSPS transcript in mature leaves followed by young leaves, shoot and roots of tobacco. In order to gain the more knowledge about gene family, we searched for the previously reported motifs and studied its structural importance on the basis of homology modelling.

Conclusions

The results presented here is a first detailed in-silico study to explore the role of EPSPS gene in forefront of different plant species. The results revealed a great deal for the diversification and conservation of EPSPS gene family across different plant species. Moreover, some of the EPSPS from different plant species may have a common evolutionary origin and may contain same conserved motifs with related and important molecular function. Most importantly, overall analysis of EPSPS gene elucidated its pivotal role in immense function within the plant, both in regulating plant growth as well its development throughout the life cycle of plant. Since EPSPS is a direct target of herbicide glyphosate, understanding its mechanism for regulating developmental and cellular processes in different plant species would be a great revolution for developing glyphosate resistant crops.

Keywords: EPSP synthase, Genome wide analysis, qPCR, Shikimate pathway

Background

Aromatic amino acids and aromatic compounds are the essential components for the plant as well as for microorganism survival and hence their biosynthesis via shikimate pathway is crucial for their continued existence. EPSPS (5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase, EC 2.5.1.1.9), is considered as the sixth crucial enzyme of the shikimate pathway, catalyzes the formation of 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate (EPSP) from shikimate-3-phosphate (S3P) and phophoenolpyruvate (PEP) in the chloroplast [1] where EPSPS, a product of this pathway, acts as a precursor for the biosynthesis of aromatic amino acid in plants and microorganism [2,3]. Two types of EPSPS from different organisms have been classified [4,5]: type I EPSPS synthases, which are mainly found in all types of plants and bacteria and are naturally sensitive to herbicide named glyphosate (GLP; N-Posphonomethyl- glycine), and type II EPSPS synthases, that have been isolated from naturally occurring specific forms of microbes and are tolerant to glyphosate. The two types of EPSPS were found to share less than 30% homology with respect to their amino acid sequences. The identification of EPSPS as primary target of the broad spectrum non-selective herbicide glyphosate has generated immense interest in characterization of the enzyme [6]. Glyphosate can starve the plants of aromatic amino acids in most of the crops and weeds by competitively inhibiting the binding of EPSPS with phosphoenol pyruvate (PEP). Moreover, glyphosate also inhibits the import of cytoplasm synthesized EPSPS protein to chloroplast, which is the site of synthesis of aromatic amino acids. However, mere overexpression of EPSPS has been found to be incapable in confering glyphosate tolerance to the transgenic plants [7]. Therefore, altered EPSPS protein, with mutations in the key residues in the binding site could render EPSPS protein incapable of binding to glyphosate, have been identified. Recent researchers have exploited these altered EPSPS to design transgenic plants that have higher tolerance to herbicide, glyphosate, as compared to the wild type plants [8-11]. As a breakthrough study, overexpression of Salmonella typhimurium EPSPS mutant (Pro101to Ser) was reported to provide glyphosate tolerance in tobacco [12]. A mutant of rice EPSPS (Pro106 to Leu) conferred better glyphosate tolerance to Escherichia coli (E. coli) and tobacco transgenic plants [13]. Alteration of single amino acid residue (alanine 100, instead of highly conserved glycine found in other naturally occurring plants and bacteria) made CP4 EPSPS (from Agrobacterium sp. Strain CP4) insensitive to glyphosate [4]. Recent insights also proved that double mutations in type I EPSPS of E. coli and tobacco (threonine to isoleucine at position 97, proline to serine at position 101) leads to shift in glycine residue (at position 96) essential for glyphosate binding, eventually leading to glyphosate tolerance [4]. Substitution of proline residue to serine at position 106 of Eleusine indica (goosegrass) EPSPS protein has been predicted to provide five-fold higher capability for glyphosate resistance than wild type plants [14].

Structurally, the 3-D structure analysis of E. coli EPSPS synthases has revealed that the enzyme consists of six aligned parallel alpha-helices in each of two similar EPSPS I domains. Their pattern of alignment creates a specific electropositive attraction for anionic ligands at an interface between the two domains [15]. The nature of active sites, especially of the glyphosate binding cleft of EPSPS synthase has remained highly unresolved. Besides that, after comparing the crystal structures of E. coli EPSPS synthase during formation of either binary complex with S3P or formation of ternary complex with S3P and glyphosate elucidated that, the two domain containing E. coli EPSPS enzyme closes on ligand binding, thus, forming the active site in the inter-domain cleft. Glyphosate inhibition was considered as competitor with respect to PEP binding to occupy its site, though the molecular mechanism for such as specific inhibitory action of this inhibitor on EPSPS synthase is still obscure [16,17].

Although, some of the members of EPSPS gene family have been identified and characterized in model plants such as tobacco and Arabidopsis thaliana (hereafter termed as Arabidopsis), a systemic approach of comparative in-silico analysis among diverse group of species is still lacking. In the present study, we have identified and comprehensively analysed the EPSPS gene family across the diverse group of species. The work involves the identification of EPSPS gene family and analysis of their gene structure, conserved motifs and phylogenetic relationship. By taking the advantage of available expression data in genevestigator for EPSPS genes, we also performed a comprehensive analysis of tissue specific expression of EPSPS gene in plants, underlying its interesting role in plant development and under different stresses. Furthermore, time-course glyphosate treatment and subsequent quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis unveiled the tissue specific expression pattern of EPSPS gene in tobacco. Ultimately, these findings will lead to potential applications for the improvement of glyphosate resistance in tobacco via genetic engineering.

Result and discussion

Sequence retrieval by data base mining of EPSPS genes yielded 91 genes from different plant species. Further filtration by decrease redundancy software resulted in 58 non-redundant, unique sequences of EPSPS genes, which were further used to obtain their molecular weight and pI. (Table 1). Since extensive information is available for fully sequenced Arabidopsis and rice as the model species, therefore, these two were used in this study. The average molecular weights of EPSPS proteins from rice and Arabidopsis were 54.3 and 49.0 respectively, while, the pI values in rice and Arabidopsis EPSPS genes ranges from 5.00-9.88 and 5.98-9.28, respectively (Table 1). These results show high divergence between the EPSPS proteins even within the same plant species. Using SignalP, most of the EPSPS proteins from both rice and Arabidopsis were predicted to localize to chloroplast and cytosol with one rice EPSPS predicted to be present in mitochondria and the secretory pathway (Table 1). With the exception of this protein, all the other predictions support the hypothesized localization given by Dello-Cioppa et al. [18], however, experimental evidence of EPSPS protein localization is still pending to be explored in future.

Table 1.

Representing EPSPS coding genes in different organisms

| Source | Accession | CDs | AA length | pI | MW (kDa) | Predicted localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lolium multiflorum |

DQ153168 |

1316 |

406 |

10.65 |

45.3 |

Chloroplast |

|

Lolium rigidum |

AF349754 |

1041 |

287 |

6.03 |

36.6 |

Cytosol |

|

Hordeum vulgare |

AK377052 |

462 |

153 |

6.72 |

16.8 |

Cytosol |

|

Triticum aestivum |

EU977181 |

1533 |

510 |

5.99 |

53.7 |

Chloroplast |

|

Triticum aestivum |

AK333537 |

1837 |

580 |

11.22 |

65.9 |

Chloroplast |

|

Bracypodium distachyon |

XM003557194 |

1533 |

510 |

7.56 |

55.8 |

Chloroplast |

|

Lolium rigidum |

AJ310166 |

957 |

299 |

8.91 |

33.3 |

Cytosol |

|

Sorghum hapalanese |

HQ436353 |

1335 |

444 |

5.30 |

47.3 |

Cytosol |

|

Oryza sativa |

NM001063247 |

1548 |

515 |

8.04 |

54.3 |

Chloroplast |

|

Oryza sativa |

AF413082 |

1536 |

511 |

8.04 |

53.9 |

Chloroplast |

|

Oryza sativa |

AB016765 |

1176 |

391 |

5.82 |

41.7 |

Cytosol |

|

Eleusine indica |

AY395700 |

1338 |

446 |

5.52 |

47.3 |

Cytosol |

|

Sorghum bicolor |

HQ436352 |

1470 |

490 |

7.59 |

51.5 |

Chloroplast |

|

Zoysia indica |

GU256772 |

1176 |

391 |

5.95 |

41.8 |

Cytosol |

|

Oryza sativa |

AK242404 |

1184 |

375 |

8.93 |

42.5 |

Cytosol |

|

Oryza sativa |

AY324880 |

995 |

317 |

9.88 |

34.9 |

Cytosol |

|

Brassica rapa |

AY512663 |

1545 |

514 |

6.99 |

55.1 |

Chloroplast |

|

Dicliptera chinensis |

AF371965 |

1551 |

516 |

7.54 |

54.9 |

Chloroplast |

|

Petunia hybrida |

M21084 |

1551 |

516 |

7.96 |

55.5 |

Chloroplast |

|

Conyza canadensis |

FR872821 |

1572 |

523 |

6.48 |

55.8 |

Chloroplast |

|

Camptotheca acuminata |

AY639815 |

1560 |

519 |

8.22 |

55.5 |

Chloroplast |

|

Capsicum annum |

JN160845 |

1551 |

516 |

7.54 |

55.3 |

Chloroplast |

|

Gossypium histurum |

FJ440839 |

1233 |

410 |

9.06 |

43.3 |

Cytosol |

|

Vitis vinifera |

FQ394893 |

1496 |

466 |

10.10 |

53.1 |

Secretory |

|

Calystegia hederacea |

EU526078 |

1563 |

521 |

7.58 |

55.4 |

Chloroplast |

|

Solanum lycopersicum |

M21071 |

1330 |

437 |

8.45 |

47.0 |

Cytosol |

|

Arabidopsis lyrata |

XM00280124 |

1563 |

520 |

8.45 |

55.7 |

cytosol |

|

Amaranthus tuberculatus |

FJ869880 |

1551 |

516 |

6.30 |

55.3 |

Chloroplast |

|

Orychophragmusviolaceus |

AF440389 |

1557 |

518 |

7.03 |

55.2 |

Chloroplast |

|

Conyza canadensis |

FR872820 |

1341 |

447 |

5.19 |

47.5 |

Cytosol |

|

Convolvulus arvensis |

EU698030 |

1560 |

519 |

6.04 |

55.2 |

Chloroplast |

|

Conyza bonariensis |

EF200072 |

1563 |

520 |

7.05 |

55.4 |

Chloroplast |

|

Oryza rufipogon |

CU861700 |

1338 |

430 |

10.38 |

49.5 |

Mitochondria |

|

Conyza sumatrensis |

AY834207 |

670 |

216 |

8.14 |

24.4 |

Cytosol |

|

A,qrqnthus rudis |

AY545657 |

1338 |

446 |

5.76 |

47.3 |

Cytosol |

|

Arabidopsis thaliana |

AY086717 |

1071 |

357 |

5.25 |

38.1 |

Cytosol |

|

Arabidopsis lyrata |

XM002894095 |

1566 |

461 |

5.98 |

49.0 |

Chloroplast |

|

Arabidopsis thaliana |

BT022026 |

1572 |

523 |

6.30 |

55.8 |

Chloroplast |

|

Acorus gramineus |

AY545656 |

1563 |

520 |

6.30 |

55.7 |

Chloroplast |

|

Populus trichocarpa |

XM002301243 |

930 |

310 |

6.28 |

33.2 |

Cytosol |

|

Ricinus communis |

XM002511646 |

1557 |

518 |

7.51 |

55.6 |

Chloroplast |

|

Allium macrostemon |

DQ462442 |

1557 |

518 |

8.26 |

55.5 |

Chloroplast |

|

Arabidopsis thaliana |

AT1G48860 |

1569 |

522 |

7.01 |

55.7 |

Chloroplast |

|

Arabidopsis thaliana |

BX816702 |

1470 |

489 |

5.71 |

52.4 |

Cytosol |

|

Phaseolus vulgaris |

DQ813667 |

1081 |

360 |

5.30 |

38.2 |

Cytosol |

|

Plantago lanceolata |

AY545665 |

1569 |

522 |

5.40 |

56.0 |

Chloroplast |

|

Lolium rigidum |

GU594896 |

795 |

265 |

6.94 |

27.9 |

Cytosol |

|

Phragmites australis |

JN580998 |

233 |

77 |

8.86 |

77.7 |

Mitochondria |

|

Sarracenia purpurea |

AY545663 |

295 |

96 |

6.92 |

107 |

Chloroplast |

|

Arabidopsis thaliana |

BX815732 |

795 |

265 |

8.70 |

27.7 |

Cytosol |

|

Oryza sativa |

AP002542 |

1815 |

565 |

9.16 |

64.0 |

Chloroplast |

|

Oryza sativa |

AB052962 |

936 |

311 |

5.00 |

34.3 |

Cytosol |

|

Helianthus salicifolius |

AY54566 |

1272 |

423 |

7.69 |

43.8 |

Secretory |

|

Lolium rigidum |

EU350204 |

792 |

264 |

6.00 |

27.5 |

Cytosol |

|

Helianthus salicifolius |

AY545662 |

189 |

63 |

9.85 |

65.2 |

Cytosol |

|

Vitis vinifera |

XM003633875 |

792 |

264 |

5.56 |

27.5 |

Cytosol |

|

Lolium rigidum |

EU350205 |

1593 |

530 |

8.00 |

56.4 |

Chloroplast |

| Lolium rigidum | EU350202 | 189 | 63 | 9.85 | 65.2 | Cytosol |

Phylogenetic analysis

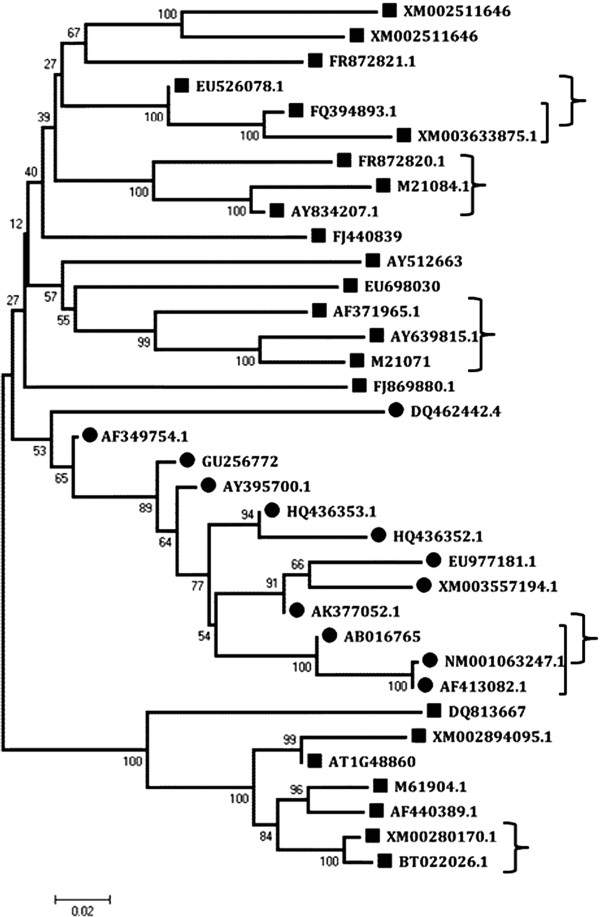

To analyze the phylogenetic relationship between EPSPS gene family members from various plant species, a phylogenetic tree, bootstrapped with 1000 replicates, was constructed using NCBI COBALT multiple sequence alignment tool. The phylogram divided the EPSPS proteins into two groups of monocot and dicot EPSPS, (Figure 1, represented by circles and squares, respectively). Although supported by low bootstrap value, this division could indicate towards divergent evolution of the EPSPS genes in monocots and dicots which probably implies that the proteins are interconnected in monocots and dicots with essential function that confers advantages to both of them. However the structural and functional importance of this divergent EPSPS evolution still remains unclear. The EPSPS phylogram supported with high bootstrap values, helped in identification of several paralogous (Figure 1, marked in squared brackets) and orthologous genes (Figure 1, marked in curly brackets).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of EPSPS genes from different plant species. The phylogram was built from sequence alignment generated from NCBI COBALT and analyzed with MEGA5. The phylogram is bootstrapped with 1000 replicates. The circles represent the monocot plant species and the squares depict EPSPS genes from dicot species. The paralogue and orthologue gene pairs are marked with square and curly brackets respectively.

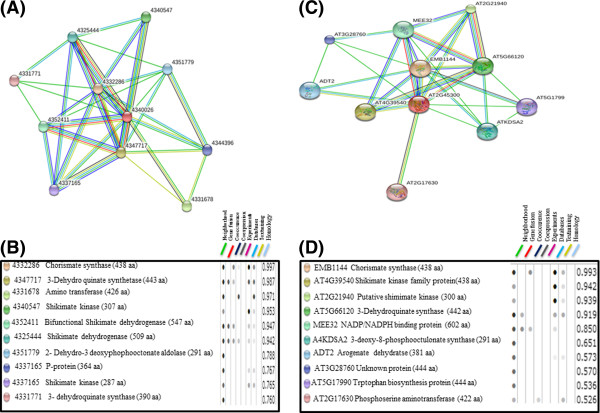

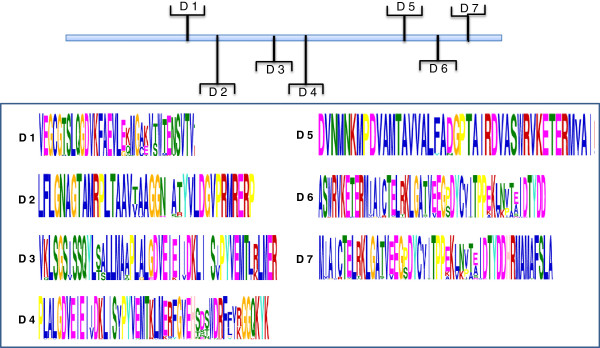

Analysis of conserved motifs

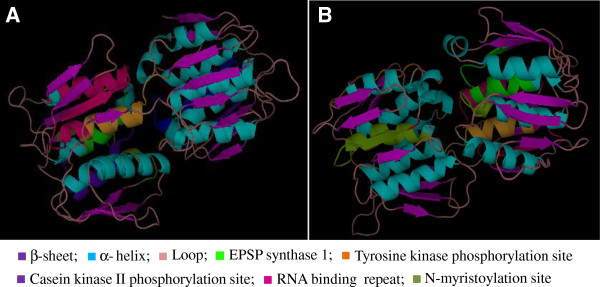

Amino acid alignment of EPSPS encoding genes from various organisms showed highly conserved regions (Supporting data, Additional file 1). The MEME suite GLAM2 version 4.8.0 was used to analyze the conserved motifs in the EPSPS proteins. A number of highly conserved motifs were observed in the EPSPS proteins from different plant species (Figure 2), indicating towards a strong conservation of these proteins during the evolution. These motifs could further provide deeper understanding that could help in gaining insights on the evolutionary relationships of plant EPSPS family. LP(G/S) KSLSNRILLLAAL and LFLGNAGTAMRPL motifs were present in almost all EPSPS plant species. These conserved residues of amino acids may function as the catalytic domains of EPSPS enzymes and are supposed to contribute in the glyphosate binding site. Similar motifs have been reported in bacterial EPSPS as well [14]. It has been proven that mutation of a single amino acid, especially lysine and arginine residue, can alter the binding site of glyphosate [19]. Besides that, substitution of an alanine residue for the second glycine residue in the conserved motifs could produce a mutant EPSPS, that exhibits a very low affinity for glyphosate [20]. To further visualize the conserved motifs of EPSPS proteins, 3-D models of rice and Arabidopsis EPSPS were generated using ESyPred 3D (web server 1.0) and visualized using PyMol. Figure 3 depicts different domains in rice and Arabidopsis EPSPS proteins as marked on their 3-D images. While, a common EPSPS I domain was found in both rice and Arabidopsis EPSPS proteins, EPSPS domain II was additionally observed in rice EPSPS protein sequence. As an exception rice harbours both of the EPSPS domains which probably indicate toward similar mode of action as in microbes. Furthermore, structurally, the EPSPS protein is composed of 35% α-helices, 17% extended sheets and 8% beta turn in rice, while Arabidopsis protein is composed of 31% α-helices, 19% extended sheets and 5% beta turn. This shows that the α-helices and the beta sheets cover comparatively larger portions of the 2-D and the 3-D structure in rice and Arabidopsis. The 3-D structure presented in the current study showed similarity with the previously observed studies wherein, bacterial EPSPSs have shown to fold in two globular domains and an inside-out α-β barrel domain with PEP-S3P binding in the interdomain cleft region [7]. In addition to that, the EPSPS interacting partners as well as its co-expression genes were also predicted in rice (Figure 4A and B) and Arabidopsis (Figure 4C and D) using String software. The analysis showed presence of several common proteins, such as chorismate synthase 2, 3-dehydroquinate synthase and shikimate kinase are found to be common interacting partners of EPSPS in both rice and Arabidopsis. Chorismate synthase catalyzes the last seventh step of the shikimate pathway which is conserved among the prokaryotes, fungi and plants for the biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids. Shikimate kinase is an ATP dependent enzyme, which catalyzes the phosphorylation of shikimate to shikimate 3-phosphate, it catalyzes the fifth step of shikimate pathway, 3-dehydroquinate synthase involves in the second step of shikimate pathway, which converts the 3-deoxy-arabinoheplutosonate 7-phosphate to 3-dehydroquinate, which have been shown to be essential for basic cellular metabolism machinery [21].

Figure 2.

Conserved domain analysis of EPSPS proteins. The upper panel of the figure depicts the location of the domains while lower panel denotes the conserved sequences of the respective domains.

Figure 3.

Structural analyses of rice and Arabidopsis EPSPS proteins. The 3-D structure analysis of (A) Rice and (B) Arabidopsis EPSPS proteins. The conserved domains of EPSPS protein have been marked in the figure.

Figure 4.

In-silico prediction of interacting partners for EPSPS gene by STRING. (A) Figure showing Interacting partners for rice EPSPS gene. (B) The key to the putative interacting partners for rice EPSPS gene is listed. (C) Interacting partners for Arabidopsis EPSPS gene. (D)The key to the putative interacting partners of Arabidopsis EPSPS gene is listed. NM_001063247 and AT2G45300 were used as the input sequences to search for the rice and Arabidopsis interactions, respectively.

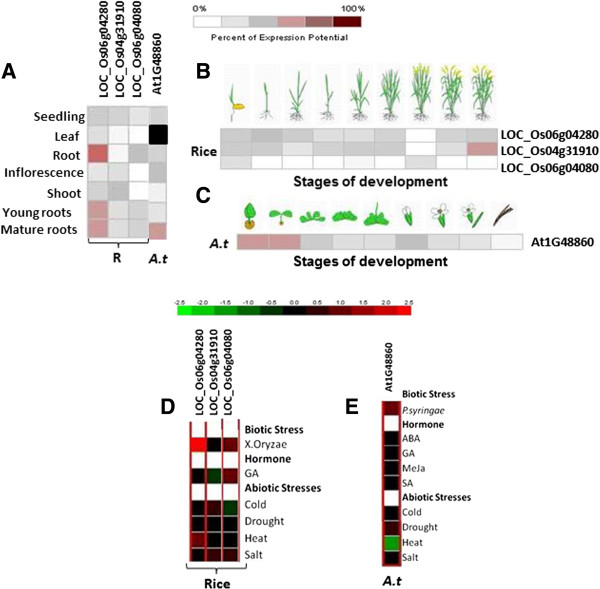

Gene expression analysis

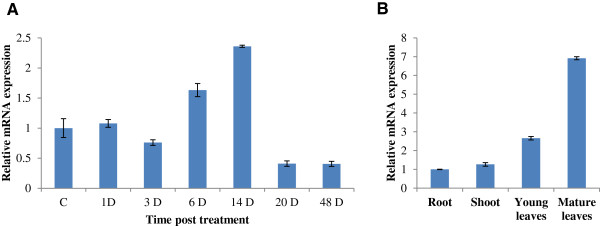

In-silico analysis of EPSPS gene expression profile in rice and Arabidopsis was performed using Genevestigator response viewer (https://www.genevestigator.com/). The data could be retrieved for three rice (LOC_Os06g04080, LOC_Os06g04280, LOC_Os04g31910) and one Arabidopsis (AT1G48860) EPSPS genes, while the probe id for EPSPS from other plant species were unavailable. The data obtained in different stress conditions along with their response in different anatomical and developmental stages of plant was retrieved as heat maps (Figure 5A, B, C and D). Relative fold induction of more than 2-folds and decrease of less than 0.5 fold in relative expression was taken as standard cut-off for upregulation and down regulation of the genes, respectively. Most of the stress conditions had only marginal effect on the expression of EPSPS genes except for the heat stress on Arabidopsis EPSPS gene (AT1G48860) and biotic stress on rice EPSPS (LOC_Os06g04280). Pathogens and some elicitors have been found to affect the expression of plant genes for proteins in the shikimate pathway [22-25]. Expression of DHS2, which encodes 3-deoxy-D-arabino heptulosonate (DAHP) synthase, a member of the shikimate pathway, is upregulated by wounding or pathogen attack in Arabidopsis [22]. Moreover, expression of genes encoding DAHP synthase, shikimate kinase (SK., EC 2.7.1.71), 5-enolpyruvyl shikimate 3-phosphate synthase and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase were found to be induced in cultured tobacco cells by elicitor treatment [23]. Apart from these, slight perturbation in rice and Arabidopsis EPSPS expression levels were observed under drought, salt and cold stresses. Among hormones, only gibberellic acid treatment altered the expression of two rice EPSPS genes (LOC_Os04g31910 and LOC_Os06g04080). The expression analysis of EPSPS genes in different plant anatomical features showed higher expression of the gene in root tissues as compared to the aerial part. Overall LOC_Os60g04080 showed very low expression in organ specific and developmental stage specific analysis, whereas LOC_Os04g31910 and LOC_Os06g04280 exhibited moderate expression throughout life cycle with LOC_Os04g31910 showing up-regulation in the senescence stage. In case of Arabidopsis, the EPSPS gene expression was highly up-regulated at the initial growth phases (from germination to two-leaf stage) followed by moderate expression during the rest of life cycle. No expression was observed in the siliques. High expression in the initial growth stages in Arabidopsis probably reflects higher requirement of aromatic amino acids at these stages of lifecycle. Overall, the analysis indicates that the gene might play some pivotal roles in maintaining well-being of the plant in different stages of life-cycle as well as under stress conditions. Since the expression profile available from the publically available databases did not account for the effect of glyphosate on the expression profile of EPSPS genes, we carried out Real-Time PCR analysis of the EPSPS genes in tobacco plant at different time points post Roundup glyphosate (Monsanto) treatment. Upon Real-Time PCR analysis, we observed a significant difference between the expression level of EPSPS gene in both time and tissue dependent manner. Interestingly, a significant induced expression of the EPSPS gene was observed 6 DPS (days post treatment) which further increased 14 DPS, after which it reduced below the control EPSPS expression level (Figure 6A). This reduction was accompanied by senescence phenotype observed in plants after 14 days, while the initial lag phase in expression (till 3DPS) could be attributed to presence of aromatic amino acids in the cellular pool which probably started depleting between 3–6 DPS and hence the EPSPS gene was induced to replenish the cellular stocks. In contrast to Arabidopsis and rice EPSPS gene expression in young tissues, the qRT-PCR analysis in tobacco revealed significantly induced expression in mature leaves followed by young leaves, shoots and roots, respectively (Figure 6B).

Figure 5.

Differential expression patterns of rice and Arabidopsis EPSPS proteins. Heat map showing differential expression profile of rice (R) and Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) EPSPS gene in different anatomical features (A), developmental stages (B & C) and stress conditions and hormonal treatments (D & E). Blackened block depicts absence of information on expression profile.

Figure 6.

Real time PCR analysis of EPSPS gene against glyphosate stress. qPCR analysis of EPSPS transcript showing their regulation in response to glyphosate treatment (A). Real time PCR analysis of EPSPS during post treatment of 2.16 mg/l glyphosate at different time points. (B). Relative mRNA expression of EPSPS gene in different parts of plant. The relative mRNA expression for each transcript was calculated in comparison to control plants. Bars indicate the standard error (± SE) calculated from three independent experiments.

Conclusions

From the present study, we can conclude that the EPSPS family is mainly characterized by the presence of EPSPS I domain which is highly conserved among different plant species. Further, the phylogenetic analysis revealed that the EPSPS gene family has diversified in species-specific manner after the monocot-dicot split. The expression analysis showed the differential tissue specific and time dependent expression of EPSPS genes which suggested their role in regulating plant growth and its development throughout the life-cycle of plant. Moreover, in-silico expression analysis also showed its role in response to various external factors like biotic and abiotic stress. The results presented here is the first detailed study to understand the role of EPSPS in plants. So far, E. coli EPSPS gene is the most extensively studied member of the EPSPS gene family but its application to develop herbicide tolerant plant has raised a number of ethical and GMO related issues. Therefore, exploration of EPSPS genes from plant origin that could aid in crop improvement is the need of the hour.

Methods

Identification of EPSPS encoding genes

A preliminary search for EPSPS genes was performed using nucleotide sequence of BT022026 (an EPSPS from Arabidopsis thaliana) as query search for BLAST search (blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and an e- value of 10-73 was chosen as the cut-off for the search. The obtained genes were pooled and redundancy was removed with decrease redundancy software (http://web.expasy.org/decrease_redundancy/). The translated sequences of the candidate genes were further analysed for the presence of specific EPSPS domains and motifs through motifscan (myhits.isb-sib.ch/cgi-bin/motif scan) and scan prosite (Prosite.expasy.nlm.nih.gov) and the genes with characteristic EPSPS domains were shortlisted for further analysis.

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis

Multiple sequence alignment of the amino acid sequences was obtained using Clustal W (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/) (Additional file 1). After manually removing the partial sequences, sequence alignment for phylogenetic tree construction was carried out using NCBI COBALT (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/cobalt/cobalt.cgi) [26] with default parameters. The fasta file thus generated was analyzed, bootstrapped with 1000 replicates and edited in Mega version 5 programme [27].

Analysis of EPSPS localization and structure

All predicted EPSPS amino acid sequences were analysed for their sub-cellular localizations via Target p 1.1 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TargetP/) [28]. The conserved motifs were identified using MEME suite- GLAM 2, version 4.8.0 using default parameters (http://meme.nbcr.net/meme/) [29]. Homology modelling of EPSPS protein was conducting by using ESyPred web server 1.0 (http://www/fundp.ac.be/sciences/biologie/urbm/bioinfo/esypred/). Molecular graphics visualization programme (PyMol, http://www.pymol.org,) was used for visualization and editing of the generated PDB model.

Interacting partners and its co-expressed genes

Interacting partners of EPSPS and its co-expressed genes were predicted with String software (http://string-db.org/) [30].

Gene expression analysis by microarray

In-silico expression profile of the EPSPS gene was analyzed at developmental and anatomical level and under various stress conditions by retrieving the expression values from affymetrix array database from Genevestigator response viewer (https://www.genevestigator.com/gv/) [31]. ATH1-22 K and Os-51 K: Rice genome 51 K arrays were chosen for the analysis of microarray data for Arabidopsis and rice respectively. For both the plants, microarray data from only the wild type background was analyzed.

Plant growth parameters and quantitative PCR analysis

Tobacco seedlings were grown in vermiculite in controlled environmental conditions of 200 μmol m-2 s-1 illumination with day and night cycle of 14 h (25°C)/8 h (18°C). After fourteen days of seed germination, 5–6 leaf staged tobacco plants were sprayed with 2.16 mg/l glyphosate (Roundup® 607 g/l (50.9 w/w), Monsanto Company, St. Louis, MO) [31] for different time points viz., 1, 3, 6, 14, 20 and 48 days. However, 14 days glyphosate treated seedlings were further divided in to root, shoot, young and mature leaves to carry out expression analysis, depending upon the experimental requirement, frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for RNA isolation. Total RNA was isolated from the tobacco plants by TRIzol reagent (Sigma Aldrich, USA) according to the manufactures instructions. Quantitative PCR analysis was performed using EPSPS gene specific primers (Forward 5′-TTGCCATGACTCTTGCCGTTGTTG-3′ and Reverse 5′- AAGGCCCGGACTACTGCATTATCA-3′) as described in Garg et al.; [32]. Three biological replicates were chosen for each sample for the expression analysis (n = 9). The expression of EPSPS gene in different samples was normalized with the expression of actin (Forward 5′- TGGTCGTACCACCGGTATTGTGTT-3′ and Reverse 5′- CCACGCTCG GTAAGGATCTTC ATC -3′) as the reference gene. The relative mRNA expression was calculated using delta CT method as described by Livak and Schmittgen (2001) [33].

The experimental research on plants have been performed with the approval of an appropriate ethics committee: Review Committee on Genetic Manipulation (RCGM)of Department of Biotechnology, Government of India (Ref. No.: BT/17/06/96-PID; dated 14/6/2012).

Abbreviations

EPSPS: 5-Enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase; qRT-PCR: quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction; PEP: Phosphoenolpyruvate; Arabidopsis: Arabidopsis thaliana; GLP: N-Posphonomethyl- glycine; E.coli: Escherichia coli; 3-D: Three dimentional; pI: Isoelectric point; DHS2 Synthase: 3-Deoxy-D-arabino heptulosonate synthase; NJ: Neighbour joining; DPS: Days post spray.

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

BG planned and performed all the experimental work. NV helped in preparation of the final draft of the manuscript. NT supervised the work and helped in the preparation of the final draft of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Amino acid alignment of EPSPS encoding genes from various organisms by using ClustalW programme.

Contributor Information

Bharti Garg, Email: bio.bharti@gmail.com.

Neha Vaid, Email: vaid@mpimp-golm.mpg.de.

Narendra Tuteja, Email: narendra@icgeb.res.in.

Acknowledgements

Work on plant stress signalling and plant transformation in NT’s laboratory is partially supported by Department of Biotechnology (DBT) and Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India.

References

- Herman KM, Weaver LM. The shikimate pathway. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1999;50:473–503. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley R. The shikimate pathway: a metabolic tree with many branches. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1999;25:307–387. doi: 10.3109/10409239009090615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts F, Roberts CW, Johnson JJ, Kyle DE, Krell T. et al. Evidence for the shikimate pathway in apicomplexan parasites. Nature. 1998;393:801–805. doi: 10.1038/31723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funke T, Han H, Healy-Fried ML, Fischer M, Schönbrunn E. Molecular basis for the herbicide resistance of Roundup Ready crops. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13010–13015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603638103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang A, Sha J, Lu W, Chen M, Li L. et al. A single residue mutation of 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase in Pseudomonas stutzeri enhances resistance to the herbicide glyphosate. Biotechnol Lett. 2008;30:1397–1401. doi: 10.1007/s10529-008-9703-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz JE, Mao MK, Sikorsski JA. Glyphosate: A unique global herbicide. Washington, DC: ACS American Chemical Society; 1997. p. 653p. [Google Scholar]

- Liang L, Wei L, Yunlei H, Shuzhen P, Wei Z. et al. A novel RPMXR motif among class II 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthases is required for enzymatic activity and glyphosate resistance. J Biotech. 2006;144:330–336. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Year GN, Hajdukiewicz PT, Broyles D, Rodriguez D, Xu CW. et al. Plastid-expressed 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase genes provide high level glyphosate tolerance in tobacco. Plant J. 2001;25:261–270. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.00958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe AR, Gasser CS, Brown SM, Padgette SR, Hart J. et al. Glyphosate as a selective agent for the production of fertile transgenic maize (Zea mays L.) plants. Mol Breeding. 2002;10:153–164. doi: 10.1023/A:1020396708088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HY, Li YF, Xie LX, Xu P. Expression of a bacterial aroA mutant, aroA-M1, encoding 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase for the production of glyphosate-resistant tobacco plants. J Plant Res. 2003;116:455–460. doi: 10.1007/s10265-003-0120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao G, Liu Y, Zhang S, Yang X, Cheng R. et al. A novel 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase shows high glyphosate tolerance in escherichia coli and tobacco plants. Plos One. 2012;7:1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comai L, Facciotti D, Hiatt WR, Thompson G, Rose RE. et al. Expression in plants of a mutant aroA gene from Salmonella typhimurium confers tolerance to glyphosate. Nature. 2012;317:741–744. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Xu H, Wei X, Ye Z, Wei L. et al. Identification of a glyphosate resistant mutant of rice 5-enolpyruvylshikimate 3-phosphate synthase using a directed evolution strategy. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:184–195. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.068577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baerson SR, Rodriguez DJ, Tran M, Feng Y, Biest NA. et al. Glyphosate resistant goosegrass. Identification of a mutation in the target enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:1265–1275. doi: 10.1104/pp.001560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallings WC, Abdel-Meguid SS, Lim LW, Shieh HS, Dayringer HE. et al. Structure and topological symmetry of the glyphosate target 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase: a distinctive protein fold. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5046–5050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.5046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönbrunn E, Eschenburg S, Shuttleworth WA, Schloss JV, Amrhein N. et al. Interaction of the herbicide glyphosate with its target enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshikimate 3-phosphate synthase in atomic detail. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1376–1380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschenburg S, Healy ML, Priestman MA, Lushington GH, Schönbrunn E. How the mutation glycine96 to alanine confers glyphosate insensitivity to 5-enolpyruvyl shikimate-3-phosphate synthase from Escherichia coli. Planta. 2002;216:129–135. doi: 10.1007/s00425-002-0908-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della-Cioppa G, Bauer SC, Taylor ML, Rochester DE, Klein BK. et al. Targeting a herbicide-resistant enzyme from Escherichia coli to chloroplasts of higher plants. Biotechnology. 1987;5:579–584. doi: 10.1038/nbt0687-579. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Liao Z, Chen M, Guo B, Jin H. et al. Characterization of 5-enolpyruvylshikimate 3-phosphate synthase gene from Camptotheca acuminate. Biol Plantarum. 2006;50:542–550. doi: 10.1007/s10535-006-0086-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huynb QK, Kisbore GM, Bild GS. 5-enolpyruvyl shikimate-3-phosphate synthase from Escherichia coli: identification of Lys-22 as a potential active site residue. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:735–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid J, Amrhein N. Molecular organization of the shikimate pathway in higher plants. Phytochem. 1995;39:737–749. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(94)00962-S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keith B, Dong X, Ausubel FM, Fink GR. Differential induction of 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase genes in Arabidopsis thaliana by wounding and pathogenic attack. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8821–8825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go¨ rlach J, Giesecke HR, Rentsch D, Regenass M, Roy P. et al. Temporally distinct accumulation of transcripts encoding enzymes of the pre chorismate pathway in elicitor-treated, cultured tomato cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3166–3170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozawa Y, Hasegawa H, Terakawa T, Wakasa K. Characterization of rice anthranilate synthase alpha-subunit genes OASA1 and OASA2. Tryptophan accumulation in transgenic rice expressing a feedback-insensitive mutant of OASA1. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:1493–1506. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.4.1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno T, Kasai K, Ikejiri-Kanno Y, Wakasa K, Tozawa Y. In vitro reconstitution of rice anthranilate synthase: distinct functional properties of the alpha subunits OASA1 and OASA2. Plant Mol Biol. 2004;54:11–22. doi: 10.1023/B:PLAN.0000028729.79034.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos JS, Agarwala R. COBALT: constraint-based alignment tool for multiple protein sequences. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1073–1079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neisen H, Engelbrecht J, Brunak S, Heijne GV. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal pepetides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1–6. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timothy LB, Mikael B, Fabian AB, Martin F, Charles E. et al. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nuc Acid Res. 2009;37:202–208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschini A, Szklarczyk D, Frankild S, Kuhn M, Simonovic M. et al. STRING V9.1: Protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nuc Acid Res. 2013;41:1. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1039. doi-10.1093/nar/gks1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruz T, Laule O, Szabo G, Wessendorp F, Bleuler S, Oertle L. et al. Genevestigator v3: a reference expression database for the meta analysis of transcriptomes. Adv Bioinform. 2008;2008:420747. doi: 10.1155/2008/420747. doi:10.1155/2008/420749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg B, Puranik S, Misra S, Tripathi BN, Prasad M. Transcript profiling identifies novel transcripts with unknown fuctions as primary response components to osmotic stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Plant Cell Tissue Organ culture. 2012;113:91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmitten TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and 2 (Delta Delta C (T)) methods. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Amino acid alignment of EPSPS encoding genes from various organisms by using ClustalW programme.