Abstract

We have utilized in vitro selection technology to develop allosteric ribozyme sensors that are specific for the small molecule analytes caffeine or aspartame. Caffeine- or aspartame-responsive ribozymes were converted into fluorescence-based RiboReporter™ sensor systems that were able to detect caffeine or aspartame in solution over a concentration range from 0.5 to 5 mM. With read-times as short as 5 min, these caffeine- or aspartame-dependent ribozymes function as highly specific and facile molecular sensors. Interestingly, successful isolation of allosteric ribozymes for the analytes described here was enabled by a novel selection strategy that incorporated elements of both modular design and activity-based selection methods typically used for generation of catalytic nucleic acids.

INTRODUCTION

Demand for biosensors has increased markedly in recent years, driven by needs in many commercial and research sectors for specific sensors that are capable of rapid, reliable measurements (1). Development of biosensors is of interest for diverse applications ranging from biochemical profiling of normal and diseased cells (metabolomics), clinical diagnostics, drug discovery and biodefense, to more straightforward analyses such as fermentation, process monitoring, environmental testing, and quality control of foods and beverages. Recently, ligand-binding nucleic acids have been established as sensitive molecular switches with potential utility as biosensors (2,3). Ribozymes, in particular, have been engineered to function as allosteric enzymes that are switched on or off in response to specific effectors (4,5). These substances include metabolites, second messengers, metal ions, enzyme cofactors, nucleotides, small molecule drugs, proteins and even post-translationally modified protein isoforms (6–11). Notably, effector-dependent RNA biosensors have even been employed in immobilized microchip formats to develop ‘chemical fingerprints’ of complex chemical or biological mixtures (12).

Historically, allosteric ribozymes have been isolated by either of two different combinatorial selection strategies. The first, modular rational design, is achieved by selection of an aptamer from a random sequence pool on the basis of specific binding to an effector molecule, and by then appending the aptamer to a known ribozyme catalytic domain via an appropriate linker region to engineer a functional effector-dependent RNA enzyme (13,14). Alternatively, in activity-based selection, a random pool consisting of ribozyme sequence variants is first incubated under reaction conditions in the absence of the desired effector. Ribozymes that show catalytic activity under these conditions are removed and discarded, while ribo zymes that are inactive are retained and then incubated in the presence of the desired effector. Ribozymes showing effector-dependent catalytic activity are isolated and carried forward in subsequent rounds of selection and purification (9,15).

Here, we describe a novel, hybrid strategy for allosteric ribozyme evolution which combines aspects of both the effector-binding and activity-based selection approaches described above. In the present study, combinatorial selections for allosteric ribozymes responsive to the small molecules caffeine and aspartame were performed using pools of random RNA sequences constrained within a functional hammer head ribozyme motif (16–18). Large initial sequence pools were first subjected to several rounds of binding- based selection using either caffeine or aspartame as the desired effector molecule. RNAs that emerged were anticipated to be enriched for sequences that both bound to the respective target molecule and possessed hammerhead ribozyme activity. Passage of effector binding-enriched subpools through several subsequent rounds of activity-based selection yielded allosteric ribozymes (designated RiboReporter™ sensors) capable of rapid detection of caffeine or aspartame over a wide range of target molecule concentrations in a fluorescence-based assay format. The hybrid strategy proved to be particularly effective in the case of the aspartame selection, which did not readily yield an allosteric ribozyme by conventional effector-binding or activity-based approaches.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Caffeine immobilization

The caffeine derivative theophylline-7-acetic acid was immobilized on epoxyaminohexyl (EAH)-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). A 6.5 ml aliquot of EAH-Sepharose was washed twice with 5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2). A 23 mg aliquot of theophylline-7-acetic acid (97 mmol), 66 mg of N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) (571 mmole) and 200 mg of 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) (104 mmol) were added to 5 ml of a 1:1 dioxane:PBS pH 7.2 solution. This solution was added to the washed EAH-Sepharose resin and the resulting slurry was incubated overnight at room temperature. After removal of the supernatant, the resin was washed with 5 ml of 1:1 dioxane:PBS pH 7.2 four times, followed by 5 ml of 0.1 M sodium acetate pH 5.3:0.1 M sodium chloride and 5 ml of 0.1 M sodium hydroxide. The resin was then washed with water until the pH of the supernatant was less than 8. The resin was stored at 4°C as a 50% slurry in 0.1% SDS. The extent of coupling was determined by treating the derivatized resin with excess 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBSA), measuring the amount of unreacted TNBSA by reaction with glycine and monitoring the reaction product at 335 nm (19). The concentration of caffeine on the resin was ∼8.3 mM (8.3 µmol/ml resin).

Aspartame immobilization

The aspartame (Asp-Phe-OCH3) derivative Asp-Phe-Cys was used to facilitate coupling to the solid support. The tripeptide was coupled to thiopropyl-Sepharose resin (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) via a disulfide linkage. A 2.6 g aliquot of thiopropyl-Sepharose powder was suspended in 50 ml of water. The resin was washed five times with 40 ml of water then three times with 40 ml of PBS pH 7.5 plus 1 mM EDTA. Then 38 mg of Asp-Phe-Cys (99 µmol) was dissolved in 17 ml of PBS plus 0.9 mM EDTA pH 8. The Asp-Phe-Cys solution was added to the resin and the slurry was incubated at room temperature. The progress of the reaction was monitored by removing aliquots and measuring the concentration of the byproduct thiopyridone at 343 nm. After 100 min, the resin was washed twice with PBS, 1 mM EDTA. The resin was stored at 4°C as a 60% slurry in PBS with 20% ethanol. The concentration of Asp-Phe-Cys on the resin was 5.5 mM (5.5 µmol/ml).

Pool templates and primers

The DNA templates JD.05.100.A (5′-AAAGGGCAACCT ACGGCTTTCACCGTTTCGN33CTCATCAGGGTCGCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTA-3′), STC.12.142.A (5′-AAAGG GCAACCCACGGCTTTCACCGTTTCGN33CTCATCAGGGTCGCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTA-3′), STC.29.114.A (5′-GCCGGATCCGGGCCTCATGTCGAAATCCAGGGT TCAGACGGATTAGATTTCAGTTTCACCGTCTTTGAGCGTTTATTCTGAGCTCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAAGCTTCGG-3′) and JD.18.25.A (5′-GGACGGAUCGCGU GAUGA-N40-AUCUCACACACCUCCCUGA-3′) encoding the pools HH33WT, HH33AG, STC.29.19.A, and N40apt, respectively, were synthesized on an Applied Biosystems Expedite at 1 µmol scale using standard phosphoramidite chemistry. The italicized nucleotides in STC.29.114.A were synthesized as 70% of the indicated nucleotide and 10% each of the three remaining nucleotides. The DNA oligonucleotides were purified on Poly-Pak II cartridges (Glen Research, Sterling, VA) using the protocol recommended by the supplier. The HH33AG pool was used in combination with the primers STC.12.143.A (5′-TAATACGACTCA CTATAGGGCGACCCTGATGAG-3′) and STC.12.143.C (5′-AAAGGGCAACCCACGGCTTTCACCGTTTC-3′). The HH33WT pool was used in combination with the primers STC.12.143.A and STC.12.143.B (5′- AAAGGGCAACCTA CGGCTTTCACCGTTTC-3′). The N40apt pool was amplified with the primers STC.12.153.A (5′-TAATACGACTCAC TATAGGACGGATCGCGTGATGA-3′) and STC.12.153.B (5′-TCAGGGAGGTGTGTGAGAT-3′). The STC.29.114.A pool was amplified with the primers STC.29.19.A (5′-CC GAAGCTTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGCTCAGAATAAACGCTCAA-3′) and STC.29.19.B (5′- GCCGGAT CCGGGCCTCATGTCGAA-3′).

Preparation of pool RNA

RNA pool molecules for the first round of selection were prepared via run-off transcription using T7 RNA polymerase under the following reaction conditions: 0.5 µM template oligo, 0.75 µM 5′ primer oligo, 40 mM Tris pH 7.8, 25 mM MgCl2, 1 mM spermidine, 0.1% Triton X-100, 5 mM NTPs, 40 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 50 000 U of T7 RNA polymerase, 37°C, overnight incubation. For pools HH33AG, HH33WT and N40apt, the reaction volume was 20 ml; for STC.29.19.A, the reaction volume was 1 ml. The reactions were quenched with 50 mM EDTA, ethanol precipitated then purified on 3 mm denaturing polyacrylamide gels (8 M urea, 10% acrylamide; 19:1 acrylamide:bisacrylamide). The full-length pool RNA was removed from the gels by electroelution in an Elutrap® apparatus (Schleicher and Schuell, Keene, NH) at 225 V for 1 h in 1× TBE (90 mM Tris, 90 mM boric acid, 0.2 mM EDTA). The eluted material was precipitated by the addition of 300 mM sodium acetate and 2.5 vol of ethanol.

Prior to use, the pool RNA was treated with RQ1 DNA polymerase (Promega) under the prescribed conditions to remove template DNA.

Aptamer selection: strategy 1

A slurry of resin containing immobilized ligand (caffeine, aspartame or ADP) was added to a disposable 1 cm column and allowed to settle to a bed volume of ∼300 µl (C-8 linked ADP agarose resin at a concentration of 1.4 µmol/ml was purchased from Sigma). The resin was washed three times with 500 µl of selection buffer (aspartame: 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM sodium phosphate, 90 mM HEPES, pH 7.1; caffeine: 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM sodium phosphate, 90 mM HEPES, pH 7.5; ADP: 50 mM HEPES 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 25 mM MgCl2) then washed three times with 5 ml of selection buffer plus 10 µg/ml tRNA. Pool RNA (20 µM in round 1, ∼2 µM in subsequent rounds) in 300 µl of selection buffer was added to the resin and incubated for 5 min. The resin was then washed approximately 12 times with 300 µl of selection buffer. Each wash fraction was incubated on the resin for 3 min. The resin was next treated with six or seven 300 µl washes with selection buffer containing ligand (5 mM for caffeine and aspartame, 4 mM for ADP) to elute any RNA molecules bound to the immobilized ligand. All fractions were quantitated using a Bioscan QC 2000 counter (Bioscan Inc., Washington, DC). In rounds subsequent to round 1, the resin and sample volumes were reduced to 200 µl and the pool RNA was first passed through a pre-column composed of acetylated EAH resin to remove matrix-binding RNAs. The elution fractions were combined and 25 mM EDTA, 40 µg of glycogen and 1 vol of isopropanol were added. The recovered RNAs were amplified by RT–PCR carried out as recommended by the enzyme manufacturer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) followed by run-off transcription to generate the pool for the next round of selection.

Production of caffeine sensors using activity-based selection

Molecules were selected on the basis of their ability to undergo self-cleavage in the presence of caffeine. Each round of the selection procedure involved two steps: negative selection in the absence of caffeine and positive selection in the presence of caffeine. A negative selection step was not included in the first round of selection. The selection was initiated by incubation of 4 × 1015 molecules of pool RNA (∼3 µM) in 2 ml of selection buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM sodium phosphate, 90 mM HEPES, pH 7.1) in the presence of 5 mM caffeine at room temperature for 135 min. The reaction was quenched by the addition of 25 mM EDTA and 140 mM NaCl, followed by addition of 1 vol of isopropanol. After centrifugation, the RNA was fractionated on a 10% denaturing acrylamide gel, precipitated, and amplified by RT–PCR using the primers STC.12.143.B and STC.12.143.A. Half of the product DNA (1.5 nmol) was used as a template for the production pool RNA for round 2.

Subsequent rounds were carried out using a similar procedure, but including a negative selection step. In round 2, pool RNA (∼3 µM) was incubated in 2 ml of selection buffer (the reaction volume was dropped in subsequent rounds and the number of input molecules was maintained at ∼1 × 1015) at room temperature for 2 h. The reaction was quenched as described for round 1, and the uncleaved, full-length pool RNA band was purified using denaturing gel electrophoresis. The recovered material was carried into the positive selection step, where it was incubated in selection buffer plus 5 mM caffeine for 2 h at room temperature (during subsequent rounds, the negative selection time was increased stepwise to ∼200 min and the positive selection time was decreased stepwise to 20 min). The reaction was quenched as previously described and the band corresponding to cleaved pool was purified using denaturing gel electrophoresis. The recovered material was amplified by RT–PCR and used as a pool template for the next round of selection.

Beginning in round 4, the protocol was modified such that the pool RNA would undergo three cycles of denaturation and refolding during each negative selection step. Briefly, pool RNA (∼3 µM, ∼0.8 nmol) was incubated in 250 µl of selection buffer at room temperature for a fixed period. The reaction was quenched by the addition of 25 mM EDTA, 300 mM NaOAc and 1 vol of isopropanol. After precipitation, the pellet was resuspended in 10 µl of 100 mM NaOH at room temperature to denature the RNA. The reaction was immediately neutralized by the addition of 12 µl of 3 M NaOAc, and the RNA was precipitated by the addition of 1 vol of isopropanol. The pellet was resuspended in selection buffer and the above protocol was repeated such that in total the pool RNA was subjected to three incubations in selection buffer and two denaturation steps during each negative selection step. The positive selection steps were conducted as described above with one modification; the positive selection reactions were quenched with 25 mM EDTA and 300 mM NaOAc.

Beginning in round 8, the activity of the pool RNA in the presence and absence of 5 mM caffeine was measured after the negative selection step. The RNA pellet resulting from the negative selection step was resuspended in 145 µl of selection buffer. A 125 µl aliquot of the solution was carried forward into the positive selection. The remaining 20 µl was divided quickly into two 10 µl aliquots. To one aliquot, 10 µl of selection buffer was added, and to the other was added 10 µl of selection buffer plus 5 mM caffeine. These reaction mixtures were incubated for a fixed period, then quenched, precipitated, and fractionated using denaturing gel electrophoresis. The extent of cleavage in the two reactions was quantitated using a Molecular Dynamics Storm Phosphoimager. The progress of the selection was monitored by calculating the ratio of the extent of cleavage in the presence of 5 mM caffeine versus the extent of cleavage in the absence of caffeine. The caffeine-dependent activity of the pool was indicated when this ratio exceeded 1.

Following round 12, the pool template was cloned using the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Eighteen colonies were isolated and the inserts were amplified by PCR using the primers STC.12.143.A and STC.12.143.B. The resulting template DNAs were purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit and the template DNA was used to program run-off transcription. Individual clone RNAs were purified by denaturing gel electrophoresis as described above.

The activity of the individual clones was measured by incubating the RNA (∼1 µM) in 20 µl of selection buffer in the presence or absence of 5 mM caffeine at room temperature for 20 min. The reactions were quenched, precipitated and the extent of cleavage was quantitated after gel electrophoresis.

Production of caffeine and aspartame sensors using hybrid selection

This approach involved enrichment of pools for molecules with the hammerhead motif that bound to caffeine or aspartame, followed by selection for activation of cleavage activity by those molecules. Two pools, HH33WT and HH33AG, were used as starting points for selections.

The binding-based portion of the selection was carried out essentially as described under ‘Aptamer selection: strategy 1’. For the caffeine sensor selections, the pool template resulting from round 4 of the selection using the HH33AG pool was amplified by PCR using the primers STC.12.143.A and STC.12.143.B to replace the active site G68 with the wild-type A68 residue, restoring the potential for catalytic activity in those pool molecules. This template and the template emerging from round 4 of the HH33WT selection were used to generate pool RNAs for activity-based selections. The transcription conditions were exactly as described for the binding-based portion of the selection. The activity-based portion of the selection was carried out as described under ‘Production of caffeine sensors using activity-based selection’.

For the aspartame sensor selections, the pool template resulting from round 5 of the selection using the HH33AG pool was amplified by PCR using the primers STC.12.143.A and STC.12.143.B to replace the active site G68 with the wild-type A68 residue, restoring the potential for catalytic activity in those pool molecules. This template and the template emerging from round 5 of the HH33WT selection were used to generate pool RNAs for activity-based selections. The transcription conditions were exactly as described for the binding-based portion of the selection.

To increase the sequence diversity of the aspartame binding pools, mutagenic PCR was performed on the templates emerging from round 5 (20). PCRs were set up using pool template (∼200 ng per 100 µl) in a PCR mix consisting of the following: 10 mM Tris pH 8.3, 50 mM KCl, 7 mM MgCl2, 2 µM STC.12.143.A, 2 µM STC.12.143.B, 1 mM dCTP, 1 mM dTTP, 0.2 mM dATP, 0.2 mM dGTP, 0.5 mM MnCl2 and 0.05 U/µl Taq polymerase. A series of amplifications and dilutions was performed, such that a minimum of 1.7 doublings per PCR cycle was achieved (94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min). After four PCR cycles, 10% of the reaction mix was transferred to a fresh PCR mix. Additional MnCl2 and Taq polymerase were added to the new reaction, and continued for four more cycles. After 16 four-cycle amplifications and 10-fold dilutions, the pool templates were purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. These mutagenized (predicted rate ∼3%) templates were used to generate pool RNAs for activity-based selections. The transcription conditions were exactly as described for the binding-based portion of the selection. The activity-based portion of the hybrid selection was carried out as described in the ‘Activity-based selection’ section.

Synthesis and use of hammerhead caffeine biosensors

To synthesize ligand-dependent hammerhead RNA sensors suitable for use in fluorescence-based assays, the structure of stem I was altered and a fluorescent label attached as indicated in Figure 6. The DNA templates for caffeine sensor clone STC.43.29.D11 and aspartame sensor clones AF.35.147.A2 and AF.35.147.E4 were amplified by PCR under standard conditions with MK.08.130.B (5′-TAATACGACTCA CTATAGGATGTCCAGTCGCTTGCAATGCCCTTTTAGACCCTGATGAG-3′) and MK.08.66.B (5′-AGACCTAC GGCTTTCACCGTTTCG-3′) as primers. Subsequently, the amplification product was used as a template for in vitro transcription. After gel purification, the RNA (30 nmol in 300 µl of H2O) was mixed with 150 µl of 1.2 M sodium acetate pH 5.4 plus 150 µl of fresh 40 mM sodium metaperiodate in H2O and incubated for 1 h on ice in the dark. Following precipitation with 600 µl of isopropanol, the 3′-oxidized RNA was resuspended in 450 µl of H2O, and 150 µl of 1.2 M sodium acetate buffer pH 5.4 and 100 µl of freshly made 40 mM fluorescein thiosemicarbazide in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) were added. The mixture was reacted for 2 h at room temperature, after which the labeled nucleic acid was precipitated, purified by gel electrophoresis on a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel, and resuspended in H2O to a final concentration of 12 µM.

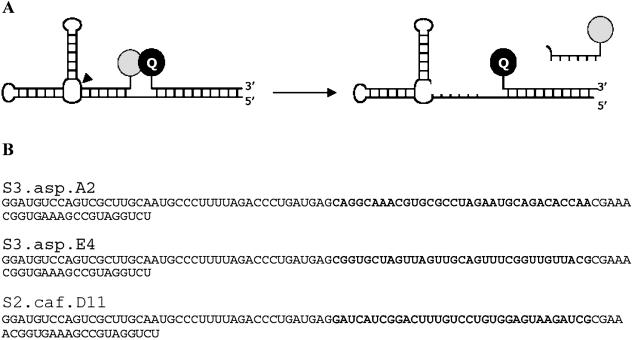

Figure 6.

Aspartame- and caffeine-dependent RiboReporter™ sensors. (A) Aspartame- and caffeine-responsive sensors were configured for a fluorescence-based read-out. Upon binding of effector, the ribozyme undergoes self-cleavage and releases a short fluorescein-labeled product oligonucleotide which generates a fluorescent signal at 535 nm upon excitation at 488 nm. (B) Nucleotide sequences of aspartame sensors S3.asp.A2 and S3.asp.E4 and caffeine-dependent sensor S2.caf.D11 including the sequence appended to the 5′ end post-selection to enable hybridization of a quenching oligonucleotide.

To perform assays, fluorescein-labeled RNA (0.5 µl/assay point) and quencher oligo 5′-Dabcyl-TGGGCATT GCAAGCGACTGGACATCC-3′ (30 pmol in 0.5 µl/assay point) in a total of 10 µl of 10 mM Tris pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl was heated to 80°C for 2 min. The mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature, and 20 µl of H2O and 20 µl of 2× assay buffer (180 mM HEPES pH 7.0–8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 20 or 50 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Na phosphate) were added. The mixture was then equilibrated for another 15 min. Cleavage reactions were performed at room temperature in black 96-well microplates, and were started by mixing 35 µl of the above nucleic acid sensor solution with 35 µl of effector ligand (20 µM–10 mM final concentration) in assay buffer (90 mM HEPES pH 7.0–8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10 or 25 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Na phosphate). The fluorescence signals were monitored in a Fusion™ α-FP plate reader and the obtained r.f.u. values were plotted against time (excitation 488 nm, emission 535 nm). The apparent reaction rates were calculated assuming the first-order kinetic model equation y = A(1 – e–kt) + NS (A = signal amplitude; k = observed catalytic rate; NS = non-specific background signal) using a curve fit algorithm (KaleidaGraph, Synergy Software, Reading, PA). Dose–response curves were generated by plotting the calculated rates versus the corresponding caffeine concentrations.

RESULTS

RNA-based sensors for caffeine and aspartame were developed using a battery of in vitro selection strategies, followed by configuration of fluorescence-based RiboReporter™ detection systems that are triggered specifically by each analyte. To have practical utility in commercial quality control or quality assurance applications, the desired RiboReporter™ systems were expected to detect caffeine or aspartame in a concentration range from 5 to 0.5 mM with assay read-times of between 5 and 20 min.

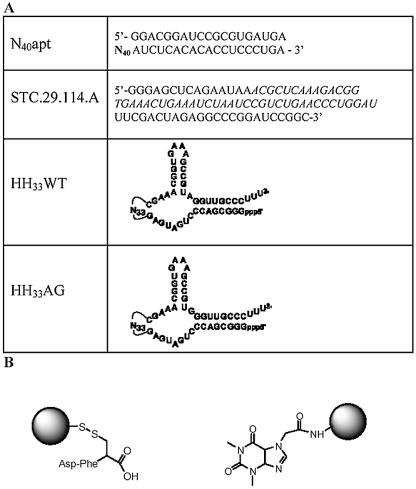

Three distinct strategies for creating RiboReporter™ sensors for caffeine and aspartame were employed. In brief, strategy 1, modular rational design, involved first selecting aptamers which bind to the target molecules from a standard, unstructured random sequence pool (N40apt), with the goal of then using the resulting aptamer sequences to build RiboReporter™ sensors. In strategy 2, activity-based selection, a pool (HH33WT) containing a hammerhead ribozyme core appended to a randomized effector-binding domain was subjected to selection on the basis of effector-dependent cleavage activity. In strategy 3, a new, hybrid method that incorporates aspects of both binding and activity-based selections, hammerhead ribozyme-based pools (HH33WT and HH33AG) were first enriched for binding to either caffeine or aspartame, and then subjected to selection on the basis of caffeine- or aspartame-dependent activity. The proposed secondary structures of the RNA pools utilized in selection strategies are shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

(A) Random sequence pools utilized in the selections and (B) structures of immobilized effector molecules, aspartame (left) and caffeine (right) coupled to Sepharose resins as described in Materials and Methods.

Strategy 1: modular rational design

Since binding-based selections require immobilization of target molecules on a solid support, caffeine and aspartame were each coupled to resin as described in Materials and Methods and depicted in Figure 1B. Caffeine was linked to EAH-Sepharose using the derivative theophylline-7-acetic acid. Similarly, aspartame (Asp-Phe-OMe) was immobilized via its C-terminus by disulfide bonding of the tripeptide Asp-Phe-Cys to activated thiol-Sepharose. SELEX experiments utilizing immobilized aspartame repeatedly failed to yield aspartame-binding aptamer sequences after nine or more rounds of selection from the unstructured N40apt pool, although a control selection against ADP performed in parallel with the same pool was enriched for ADP binders in as few as three rounds (Fig. 2A). A caffeine-binding sequence (21) of undefined secondary structure was used as a starting point for the modular design approach. In an attempt to identify the core binding element, the caffeine-binding sequence STC.29.19.E (5′GGGAGCTCAGAATAAACGC TCAAAGACGGTGAAACTGAAATCTAATCCGTCTGAACCCTGGATTTCGACATGAGGCCCGGATCCGGC3′) was partially doped with 70% wild-type, 30% non-native sequence at residues 24–63, to generate a pool of molecules for subsequent ‘biased’ selection. After five rounds of selection utilizing immobilized caffeine, 37% of the pool was specifically eluted from the column by 5 mM caffeine. The sequences of 34 of the resulting clones (Fig. 2B) were obtained. Unfortunately, as there were no conserved residues and no evidence of co-variation, the sequences did not yield clues that could have guided swift prediction of a minimal caffeine-binding element. Thus, though a modular design strategy has been used successfully to engineer a number of allosteric ribozymes from aptamers (5,8,9,22–25), this approach proved to be an ill-suited starting point for development of both aspartame and caffeine-responsive sensors.

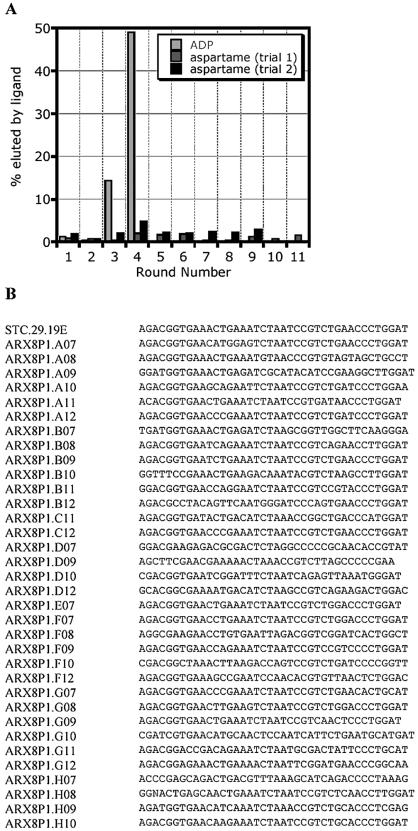

Figure 2.

(A) Progression of the selection for an aspartame aptamer using the N40apt pool. The percentage of pool RNA specifically eluted from the aspartame- or ADP-derivatized resin is plotted versus the round of selection. (B) Sequences of the random regions of clones obtained from the doped reselection using the pool STC.29.114.A. Primer sequences are not shown.

Strategy 2: activity-based selection

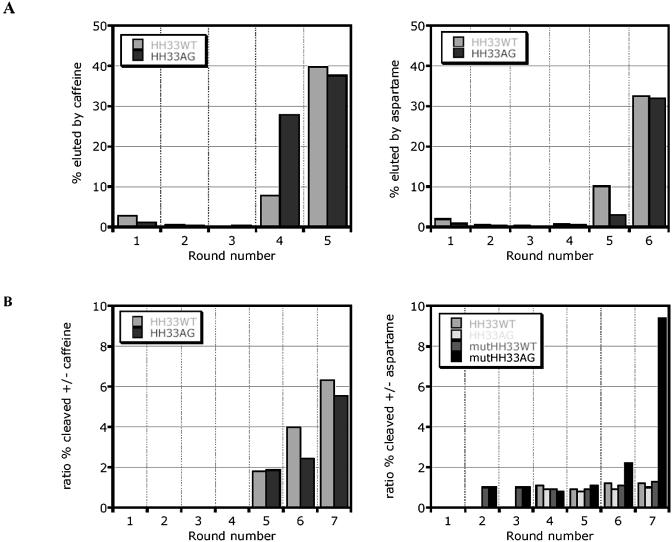

Pool molecules consisting of a self-cleaving hammerhead ribozyme core appended to a randomized effector-binding domain were subjected to selection on the basis of activity in the presence of either caffeine or aspartame. During selection, cleaved and uncleaved RNAs were separated using denaturing gel electrophoresis, and the extent of cleavage was quantified. Completion of activity-based selection was indicated by substantially more ribozyme cleavage in the presence relative to the absence of effector. The progress of aspartame- and caffeine-based selections is represented in Figure 3.

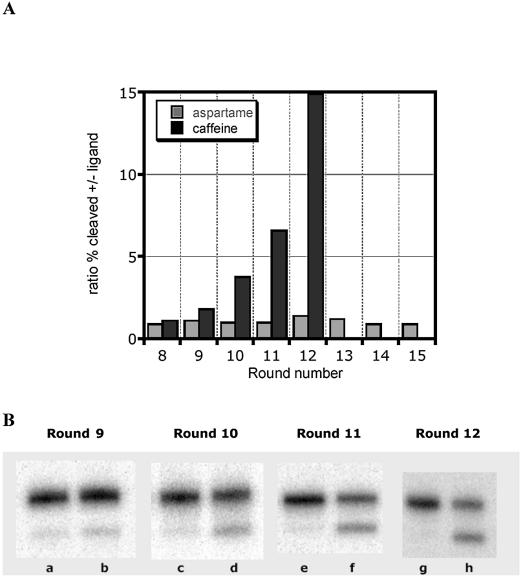

Figure 3.

Progression of strategy 2, activity-based selections. (A) Graphic representation: in each round, beginning with round 8, the activity of the pool in the presence and in the absence of 5 mM aspartame or caffeine was measured. Ratios >1 indicate increased activity in the presence of ligand. (B) Analysis of hammerhead ribozyme cleavage. The extent of cleavage of radiolabeled RNA was determined by denaturing gel electrophoresis in rounds 9–12 of the activity-based selections for a caffeine sensor. Cleavage of the pool was measured in the presence (b, d, f and h) or absence (a, c, e and g) of 5 mM caffeine.

Caffeine- but not aspartame-dependent pools were enriched through this conventional, activity-based selection (Fig. 3A). After 16 rounds, the aspartame selection showed no significant effector-dependent activity. In contrast, the caffeine selection began to show enrichment at round 9, and finally the pool showed ∼15-fold cleavage activation by caffeine in round 12 (Fig. 3B). At this point, the caffeine pool was cloned, and individual sequences were tested for caffeine-dependent activity. In a 20 min assay, 11 out of 19 clones were activated >10-fold by 5 mM caffeine (data not shown). The most active clones were then evaluated in the sequence context required for the fluorescence-based assay, revealing clones S2.caf.D11 and S2.caf.C2 as the most promising.

Strategy 3: hybrid selection

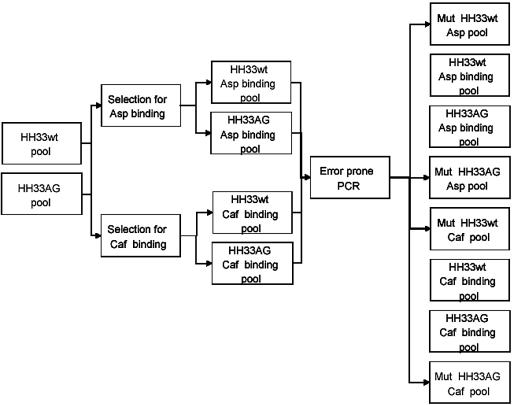

The hybrid approach involved first selection for RNA molecules incorporating the hammerhead motif that bind to either caffeine or aspartame, followed by selection for activation of cleavage by these effector molecules. Two pools, HH33WT and HH33AG, were utilized as starting points for strategy 3 selections (Fig. 1). The HH33AG pool included a catalytically inactive guanosine residue at the active site of the hammerhead motif. This pool design was meant to prevent the loss of highly active effector-dependent ribozymes by activation on the resin and elimination during the washing steps. Prior to initiating the activity-based selection phase of strategy 3, each of these pools was split into two fractions and one half was subjected to error-prone PCR. The object was to reintroduce diversity into the ligand-binding pools to increase the possibility that sequences allowing ligand activation would be present. Figure 4 is a schematic representation of the origin of the eight pools generated for activity-based selection.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the steps in the third, hybrid selection strategy. (Pools Mut HH33wt Caf and Mut HH33AG Caf were not carried forward into selection.)

Enrichment for sequences binding to immobilized caffeine and aspartame targets after several rounds of selection was seen for both pools (Fig. 5). It is interesting to note that we were unable to select aspartame binders with the unstructured pool N40apt, while the more structurally constrained hammerhead-based pools HH33WT and HH33AG both yielded aspartame binders. We speculate that some degree of conformational rigidity in the RNA was required to compensate for the conformational flexibility of the aspartame molecule.

Figure 5.

(A) Binding phase of the selection. The percentage of pool RNA specifically eluted from the caffeine- or aspartame-derivatized resin is plotted versus the round of selection. (B) Activity-based phase of the strategy 3 selections, represented as in (A).

The pools were carried into activity-based selections that were carried out essentially as described for strategy 2. The progress of selection was monitored by measuring the extent of ribozyme cleavage in the presence versus the absence of 5 mM effector (Fig. 5). Unlike the strict activity-based selection, the hybrid selection procedure yielded both caffeine- and aspartame-dependent pools. Three of the selections yielded a positive, effector-dependent signal after several rounds of selection: AspMutHH33AG, CafHH33WT and CafHH33AG. It is interesting to note that mutagenesis of the AspHH33AG pool in between the binding-based and activity-based portion of the selection may have facilitated the isolation of aspartame-dependent catalysts, as this pool showed enrichment while the others did not at this point in the selection. The three pools were cloned and individual members were assayed. Twenty-four clones from the two caffeine-dependent pools were analyzed, identifying four clones with caffeine activation factors greater than 10 (5 mM caffeine, 20 min assay). The two best clones, S3.caf.A2 and S3.caf.A6, were activated ∼35-fold by caffeine. Sequence data for 48 clones emerging from the AspMutHH33GA pool revealed that a dominant sequence had emerged. The sequence, referred to as S3.asp.A2, is activated ∼50-fold by 5 mM aspartame in a 20 min assay, as analyzed by denaturing gel electrophoresis.

Characteristics of individual sensors in a fluorescence-based assay format

Individual caffeine- and aspartame-dependent hammerheads were converted into fluorescence-based RiboReporter™ sensors as described in Materials and Methods. The fluorescent substrate is coupled to the ribozyme in cis, as depicted in Figure 6. It is worth noting that the cis configuration [as opposed to a trans configuration, see Frauendorf and Jaschke (7) and Jenne et al. (26)] comprises a robust sensor in which the cleavage reaction follows first-order kinetics. Thus, cis-acting sensor activity is independent of both the absolute signal value and the concentration of ribozyme molecules, rendering measurements relatively insensitive to fluctuations in signal strength, such as those that may result from pipetting errors or fluorescence quenching. We have observed that under optimized conditions, sensors configured in the cis configuration typically read out analyte concentration with coefficients of variation of 3–10% (data not shown).

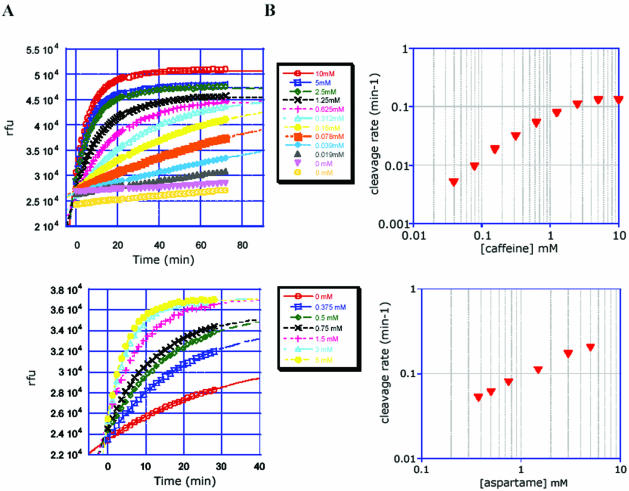

Analysis of candidate sensors in the fluorescence-based assays identified both caffeine (S2.caf.D11) and aspartame (S3.asp.E4; S3.asp.A2) sensors that meet the desired read-time and analyte concentration specifications. The properties of these three RiboReporter™ systems are described below. In general, the intensity of the fluorescence signal generated by the RiboReporter™ sensors depended on a variety of factors. Apart from the purity of sensor and quencher preparations, the pH of the assay buffer had a substantial effect. With increasing pH, the basal fluorescence of the quenched sensor increased, while the maximal fluorescence signal remained largely unchanged. Accordingly, the relative signal strength was observed to decrease at higher pH values. A similar progressive reduction in signal was observed upon addition of magnesium chloride. However, since first-order rate analysis is independent of absolute signal values, these effects did not adversely impact sensor performance.

Aspartame sensors S3.asp.E4 and S3.asp.A2

S3.asp.E4 yielded a clear linear (slope = 0.54; R2 = 0.996) dose–response curve at pH 7.5 and 40 mM MgCl2 (Fig. 7) when data from either 30 min or shorter read-times (data not shown) were used to calculate reaction rates. The catalytic background rate is ∼0.03 min–1, well below the rates for the aspartame-dependent reaction at the effector concentrations measured.

Figure 7.

Caffeine- and aspartame-dependent RiboReporter™ sensor assays. (A) Measurement of fluorescence at 535 nm versus time at various concentrations of caffeine (S2.caf.D11) or aspartame (S3.asp.E4). The activity of clone S3.asp.E4 was determined in assay buffer at pH 7.5 in the presence of 40 mM MgCl2, and clone S2.caf.D11 was tested in assay buffer at pH 7.0, 10 mM MgCl2. (B) Sensor cleavage rates versus effector concentration calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

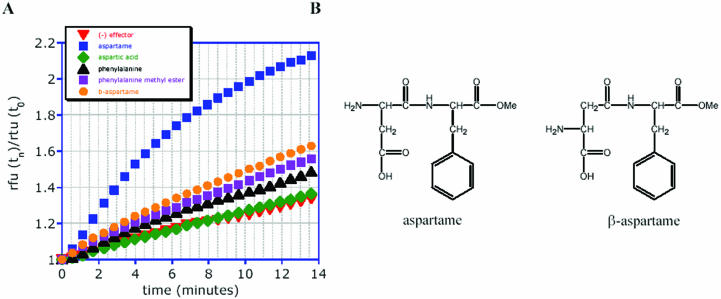

In the hammerhead ribozyme sequence context used for selection, S3.asp.A2 is activated ∼50-fold by 5 mM aspartame in a 20 min assay, as measured by denaturing gel electrophoresis (data not shown). The exquisite specificity of the aspartame-dependent sensors is illustrated by the finding that neither sensor S3.asp.A2 (Fig. 8) nor S3.asp.E4 (data not shown) was activated by closely related molecules such as β-aspartame, or by phenylalanine, a breakdown product of aspartame.

Figure 8.

Specificity of the aspartame sensor S3.asp.E4. (A) Fluorescence intensity at 488 nm at time (n) versus time (0) for the sensor activated by a series of aspartame derivatives and analogs in assay buffer, pH 7.5, 25 mM MgCl2. (B) Chemical structures of aspartame and β-aspartame.

Caffeine sensor S2.caf.D11

S2.caf.D11 was assayed at pH 7.0, in the presence of 10 mM MgCl2 with concentrations of caffeine ranging from 10 mM to 20 µM. The fluorescence signal developed rapidly, and showed good sensitivity, even within the first 5 min of the assay. Reaction curves and plots of log [rate] versus log [caffeine] are shown in Figure 7. The rate of fluorescent signal generation at 535 nm was clearly dose dependent, with a linear (slope = 0.846; R2 = 0.997) range between 20 µM and 1 mM of effector, the latter being the apparent Kd of the sensor–caffeine interaction. Furthermore, the dose–response was still measurable between 1 and 5 mM caffeine, enabling construction of a suitable calibration curve. Various allosteric ribozymes derived from an aptamer with remarkable specificity for theophylline versus caffeine (27) have been reported (5,7,9,22,25,28,29). As theophylline and other xanthine derivatives are not significant contaminants in the anticipated applications (e.g. analysis of caffeine-containing beverages), we did not assay this sensor for specificity versus theophylline, nor did we use modified selection techniques, such as those employed by Jenison (27) to drive the specificity for caffeine versus other xanthines. Since there are a number of examples of incorporation of highly specific aptamers (e.g. theophylline, ERK, ADP) into allosteric ribozymes without a loss in analyte specificity (5,11,28–30), we anticipate that such selection techniques could be successfully incorporated into the hybrid selection method.

DISCUSSION

In this work, a novel, hybrid selection strategy was devised and utilized to generate caffeine- or aspartame-dependent RiboReporter™ sensors. The hybrid approach is derived from established methods for allosteric ribozyme isolation: (i) modular rational design or (ii) activity-based selection. However, the hybrid strategy described here combines aspects of conventional selection approaches in a manner that has not been described previously, and that allowed successful development of ribozyme sensors for small molecule analytes for which conventional selection strategies proved inadequate.

Allosteric ribozymes that are responsive to small molecule effectors have been engineered in a rational design process that exploits the modular character of many RNA functional domains (self-cleaving hammerheads, ligases) and makes use of Watson–Crick base pairing rules, RNA duplex thermostability and conformational changes (14). An aptamer (or targeting) domain provides specificity for the desired effector molecule. The aptamer domain is selected in vitro on the basis of effector binding and is appended to the ribozyme module through an appropriate linker or transduction sequence. Though a validated method for allosteric ribozyme engineering, binding-based methods have the disadvantage that selections are carried out under conditions that are disengaged from enzymatic activity. Additionally, they require that the secondary structure of the core ligand-binding element is known. In the present work, aptamer targeting modules for aspartame could not be selected readily from RNA pools under standard conditions. Recently, a DNA pool enriched for binding to immobilized aspartame was identified through in vitro selection procedures. However, this pool has an unusual composition including chemically modified dTTP nucleotides that may have positively influenced the outcome of the binding-based selection (31). Though an RNA aptamer specific for caffeine had been reported at the outset of this study (21), its use as a targeting module in a ribozyme sensor would have been possible only following an extensive and time-consuming effort to minimize and optimize the binding sequence. Alternatively, success of activity-based selection relies on the likelihood of recovering rare, active molecules from a vast population of random sequence or mutagenized RNAs. This approach can be limited by the paucity of ribozymes in a starting sequence pool that will simultaneously display both high affinity effector binding and allosterically controlled enzymatic activity.

These drawbacks are addressed substantially by the hybrid selection strategy employed here, which proved to be an effective route for development of both caffeine- and aspartame-responsive ribozyme sensors. In the case of the aspartame selection, the hybrid procedure enabled isolation of functional effector-dependent ribozymes under circumstances in which reliance on either binding or activity-based selection methodologies alone failed to yield an aspartame-responsive enzyme. Representatives of each class of effector-dependent ribozyme generated via the hybrid selection approach were configured to perform in a fluorescence-based format. The resulting RiboReporter™ sensors detected their respective analytes in a dose-dependent manner with assay read-times within 5–20 min (or longer, if desired). These specifications make the sensors potentially suitable for a variety of uses, for example in product quality control or quality assurance testing. We envisage that the selection strategy described here can be generalized to enable development of allosteric ribozyme sensors for diverse commercial or biomedical applications.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Geoff White and Luisa Roberts for helpful discussions, Srikanth Krishnamurthy for technical assistance, and Judy Healy for her assistance with preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Keusgen M. (2002) Biosensors: new approaches in drug discovery. Naturwissenschaften, 89, 433–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breaker R.R. (2002) Engineered allosteric ribozymes as biosensor components. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol., 13, 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurz M. and Breaker,R.R. (1999) In vitro selection of nucleic acid enzymes. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol., 243, 137–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soukup G.A. and Breaker,R.R. (1999) Nucleic acid molecular switches. Trends Biotechnol., 17, 469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soukup G.A. and Breaker,R.R. (1999) Engineering precision RNA molecular switches. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 3584–3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koizumi M., Soukup,G.A., Kerr,J.N. and Breaker,R.R. (1999) Allosteric selection of ribozymes that respond to the second messengers cGMP and cAMP. Nature Struct. Biol., 6, 1062–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frauendorf C. and Jaschke,A. (2001) Detection of small organic analytes by fluorescing molecular switches. Bioorg. Med. Chem., 9, 2521–2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robertson M.P. and Ellington,A.D. (1999) In vitro selection of an allosteric ribozyme that transduces analytes to amplicons. Nat. Biotechnol., 17, 62–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robertson M.P. and Ellington,A.D. (2000) Design and optimization of effector-activated ribozyme ligases. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 1751–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seiwert S.D., Stines Nahreini,T., Aigner,S., Ahn,N.G. and Uhlenbeck,O.C. (2000) RNA aptamers as pathway-specific MAP kinase inhibitors. Chem. Biol., 7, 833–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaish N.K., Dong,F., Andrews,L., Schweppe,R.E., Ahn,N.G., Blatt,L. and Seiwert,S.D. (2002) Monitoring post-translational modification of proteins with allosteric ribozymes. Nat. Biotechnol., 20, 810–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seetharaman S., Zivarts,M., Sudarsan,N. and Breaker,R.R. (2001) Immobilized RNA switches for the analysis of complex chemical and biological mixtures. Nat. Biotechnol., 19, 336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breaker R.R. and Joyce,G.F. (1994) Inventing and improving ribozyme function: rational design versus iterative selection methods. Trends Biotechnol., 12, 268–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang J. and Breaker,R.R. (1997) Rational design of allosteric ribozymes. Chem Biol, 4, 453–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breaker R.R. (1997) In vitro selection of catalytic polynucleotides. Chem. Rev., 97, 371–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uhlenbeck O.C. (1987) A small catalytic oligoribonucleotide. Nature, 328, 596–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haseloff J. and Gerlach,W.L. (1988) Simple RNA enzymes with new and highly specific endoribonuclease activities. Nature, 334, 585–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forster A.C. and Symons,R.H. (1987) Self-cleavage of plus and minus RNAs of a virusoid and a structural model for the active sites. Cell, 49, 211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antoni G., Presentini,R., Neri P. (1983) A simple method for the estimation of amino groups on insoluble matrix beads. Anal. Biochem., 129, 60–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson D.S. and Keefe,A.D. (2000) Random mutagenesis by PCR. Curr. Protocols Mol. Biol., Suppl. 51, 8.3.1–8.3.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polisky B., Jenison,R.D. and Gold,L. (1995) High-affinity nucleic acids that discriminate against caffeine. US Patent 5, 580,737.

- 22.Soukup G.A., Emilsson,G.A. and Breaker,R.R. (2000) Altering molecular recognition of RNA aptamers by allosteric selection. J. Mol. Biol., 298, 623–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jose A.M., Soukup,G.A. and Breaker,R.R. (2001) Cooperative binding of effectors by an allosteric ribozyme. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 1631–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartig J.S., Najafi-Shoushtari,S.H., Grune,I., Yan,A., Ellington,A.D. and Famulok,M. (2002) Protein-dependent ribozymes report molecular interactions in real time. Nat. Biotechnol., 20, 717–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kertsburg A. and Soukup,G.A. (2002) A versatile communication module for controlling RNA folding and catalysis. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 4599–4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenne A., Hartig,J.S., Piganeau,N., Tauer,A., Samarsky,D.A., Green,M.R., Davies,J. and Famulok,M. (2001) Rapid identification and characterization of hammerhead-ribozyme inhibitors using fluorescence-based technology. Nat. Biotechnol., 19, 56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jenison R.D., Gill,S.C., Pardi,A. and Polisky,B. (1994) High-resolution molecular discrimination by RNA. Science, 263, 1425–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sekella P.T., Rueda,D. and Walter,N.G. (2002) A biosensor for theophylline based on fluorescence detection of ligand-induced hammerhead ribozyme cleavage. RNA, 8, 1242–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson K.M., Syrett,H.A., Knudsen,S.M. and Ellington,A.D. (2002) Group 1 aptazymes as genetic regulatory switches. BMC Biotechnol., 2, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Srinivasan J., Cload,S., Hamaguchi,N., Kurz,J., Keene,S., Kurz,M., Boomer,R., Blanchard,J., Epstein,D., Wilson,C. and Diener,J. (2004) ADP-specific sensors enable universal assay of protein kinase activity. Chem. Biol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saitoh H., Nakamura,A., Kuwahara,M., Ozaki,H. and Sawai,H. (2002) Modified DNA aptamers against sweet agent aspartame. Nucleic Acids Res., Suppl., 215–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]