Abstract

Two-phase study methods, in which more detailed or more expensive exposure information is only collected on a sample of individuals with events and a small proportion of other individuals, are expected to play a critical role in biomarker validation research. One major limitation of standard two-phase designs is that they are most conveniently employed with study cohorts in which information on longitudinal follow-up and other potential matching variables is electronically recorded. However for many practical situations, at the sampling stage such information may not be readily available for every potential candidates. Study eligibility needs to be verified by reviewing information from medical charts one by one. In this manuscript, we study in depth a novel study design commonly undertaken in practice that involves sampling until quotas of eligible cases and controls are identified. We propose semiparametric methods to calculate risk distributions and a wide variety of prediction indices when outcomes are censored failure times and data are collected under the quota sampling design. Consistency and asymptotic normality of our estimators are established using empirical process theory. Simulation results indicate that the proposed procedures perform well in finite samples. Application is made to the evaluation of a new risk model for predicting the onset of cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: Biomarker, Nested case, control study, Prediction accuracy, Prognosis, Quota sampling, Risk prediction

1 Introduction

Accurate assessment of an individual's risk of disease may lead to more effective disease prevention strategies. The validation of the performance of a biomarker for predicting future risk (risk marker) is often conducted with prospective cohort studies, where individuals with biomarkers measurement at baseline are followed over time till the occurrence of the clinical events of interest or the termination of the study. One major challenge in this setting is that the ascertainment of biomarker information for the full cohort can be very costly both with regard to the expense of performing assays and depletion of precious stored specimens, especially for research of rare chronic diseases. Two-phase study methods, in which more detailed or more expensive exposure information is only collected on a sample of individuals with events and a small proportion of other individuals, have been widely used in epidemiologic research of rare disease association study. Ross Prentice is amongst those who recognizes the importance of two-phase design and contributed greatly to the improvement of the design and analysis of disease prevention trials and observational studies (Prentice 1986). Commonly used two-phase designs for censored failure time data include the case cohort (CCH) study (Prentice 1986) and the nested case control (NCC) study (Thomas 1977). These methods are expected to play critical roles in biomarker validation research as well (Rundle et al. 2005; Pepe et al. 2008b; Cai and Zheng 2012).

A major limitation of these standard two-phase designs is that they require an identified cohort in which all individuals have complete data available on variables relating to eligibility, event status, follow-up and risk factors. However for many, perhaps most, practical situations, such information is not readily available for all subjects at the sampling stage. Typically some data items for individuals need to be determined by reviewing information from medical records and other sources. As a consequence, membership in sampling strata or risk sets is not always available, and the random sampling required by case–cohort and nested case–control designs is not feasible. This is an important issue that limits the use of these designs in practice. A more practical design, which we call the quota sampling design, is to sequentially review data for potentially eligible individuals until the required numbers of subjects is obtained for each stratum or risk set. For example, Habel et al. (2006) conducted a study aiming to evaluate the predictive capacity of a tumor gene expression ‘recurrence score’ for breast cancer prognosis. The study population consisted of 4,964 Kaiser Permanent patients diagnosed with breast cancer from 1985 to 1994. A NCC design was employed to obtain expression measurements. Patients who died from breast cancer were considered as cases. For each case, her eligible controls were defined as those patients who survived for at least as long as the case (in the case's risk set), matched by age, race, adjuvant tamoxifen, and diagnosis year. However, random sampling from the matched risk sets was not feasible since investigators could not confirm eligibility without a review of all medical records. Habel et al. (2006) employed an alternative sampling strategy, the quota sampling design. For each identified case, potentially eligible controls from the risk set were sequentially sampled and eligibility criteria determined for them until the desired number of eligible subjects was obtained for assessment of the recurrence score from stored tissues. While standard methods, namely conditional logistic regression, can be used to calculate relative risks with this design, the sampling scheme presents a challenge in evaluating the predictive performance of risk models that include the recurrence score.

Validation of a novel risk prediction model entails both discrimination and calibration analyses. It has been well appreciated that a single metric such as the C-statistic may be inadequate for evaluating the clinical utility of a risk prediction model/marker (Cook 2007). Predictiveness curve analysis, displaying risk distributions for cases and controls separately, has been advocated as an alternative to the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis for dichotomous outcomes (Pepe et al. 2008a). Net Reclassification Improvement (NRI) and Integrated Discrimination Improvement (IDI) have also been proposed to assess improvement in risk reclassification in the context of comparing two risk models (Pencina et al. 2008). These new metrics provide useful tools for evaluating risk prediction models with binary outcome data. However, since a risk model is often used for predicting an individual's outcome in the future, it is essential to incorporate the additional dimension of time into these metrics. However methods to estimate risk distributions and prediction measures are not well developed for cohort data with censored failure time outcome.

The sampling methods employed for the aforementioned breast cancer study represent one variation on the classic NCC design. Borgan et al. (1995) proposed estimators of both hazards ratios and absolute risks under a number of designs, including a quota sampling design that is similar to the design used in the aforementioned breast cancer study. Similar to their counterparts for the classic NCC design (Goldstein and Langholz 1992; Langholz and Borgan 1997), estimators of hazard ratios under quota sampling are calculated using the partial likelihood of the Cox proportional hazards regression model, and asymptotic properties are formally derived with counting process formulation and martingale theory (Andersen and Gill 1982). However, the predictive performance of a risk model is not characterized by relative or absolute risks. Rather, it requires estimating the population distribution of risk and related summary indices (Gu and Pepe 2009). Existing statistical procedures do not provide estimates of these entities. Recently Cai and Zheng (2012) proposed inverse probability weighting (IPW) based estimators for time-dependent ROC curves through a Cox model under the classic NCC design. However the methods can not be applied to the more complex NCC studies with quota sampling as adopted in the breast cancer study example. In this paper, we propose methods for calculating a wide variety of novel prediction indices beyond the ROC curves, accommodating the more complex quota sampling NCC designs. Furthermore, to enhance the robustness for risk model validation, we extend the modeling framework to a general class of transformation models that includes the Cox model as a special case.

The manuscript is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we specify models and define notations under NCC studies with quota sampling. In Sect. 3, we describe procedures for estimating time-dependent risk functions under a NCC study with quota sampling. In Sect. 4, we define measures of predictive performance suitable for event time outcomes and describe estimation procedures under quota NCC sampling. We study the theoretical properties of the proposed estimators in Sect. 5. We then describe simulation studies to evaluate the performance of the proposed estimators. The results are reported in Sect. 6. An application of our procedures to risk models for cardiovascular disease is presented in Sect. 7. Concluding remarks are provided in Sect. 8.

2 Model specification and quota sampling designs

2.1 Notation

Suppose we have a cohort of N individuals from the targeted population followed prospectively. Due to censoring, the observed data consist of N i.i.d copies of the vector,

= {Di = (Xi, δi,Yi,Zi)T, i = 1,…, N}, where Xi = min(Ti, Ci), δi = I(Ti ≤ Ci) where Ti and Ci denote failure time and censoring time, respectively. Additionally, Yi is the risk marker measured at time 0, and Zi is a vector of matching variables used for constructing the NCC subset. For the ease of presentation, we focus on the setting that Z has been discretized and takes L unique values {z1,…,zL}. We let Vi denote a binary random variable with Vi = 1 if subject i is ever selected either as a case or a control in the two-phase sampling for the ascertainment of Yi. Define

= {Di = (Xi, δi,Yi,Zi)T, i = 1,…, N}, where Xi = min(Ti, Ci), δi = I(Ti ≤ Ci) where Ti and Ci denote failure time and censoring time, respectively. Additionally, Yi is the risk marker measured at time 0, and Zi is a vector of matching variables used for constructing the NCC subset. For the ease of presentation, we focus on the setting that Z has been discretized and takes L unique values {z1,…,zL}. We let Vi denote a binary random variable with Vi = 1 if subject i is ever selected either as a case or a control in the two-phase sampling for the ascertainment of Yi. Define

i(t) = I(Xi ≤ t)δi and π(t) = P(Xi ≥ t). We assume the risk

i(t) = I(Xi ≤ t)δi and π(t) = P(Xi ≥ t). We assume the risk

t(Y) = P(T ≤ t |Y) follows a semi-parametric transformation model (Cheng et al. 1995, 1997; Zeng and Lin 2006)

t(Y) = P(T ≤ t |Y) follows a semi-parametric transformation model (Cheng et al. 1995, 1997; Zeng and Lin 2006)

| (1) |

where H(t) is an increasing function,

0 is some distribution function, and

0 is some distribution function, and

1(x) =

1(x) =

0{log(x)}. This is a general formulation that includes a wide range of commonly used survival models, such as the proportional hazards model (Cox 1972) and the proportional odds model (Pettitt 1984; Murphy et al. 1997).

0{log(x)}. This is a general formulation that includes a wide range of commonly used survival models, such as the proportional hazards model (Cox 1972) and the proportional odds model (Pettitt 1984; Murphy et al. 1997).

2.2 Quota sampling NCC designs and sampling probabilities

In a standard covariate-matched NCC study, all individuals observed to have an event with δj = 1 are selected as cases for further evaluation of marker Y. At each case's failure time Xj, a random sample of size m is selected without replacement from the matched risk set Rz(Xj) = {i : Xi ≥ Xj,Zi = z} whose size is

. Note that setting all Zi = 1 is equivalent to the setting that no additional matching on covariates is considered. Under such a design, the probability that the ith subject is selected into the NCC subset given

is p̂i = δi +(1 − δi) {(1 − ĜZi(Xi)} with

is p̂i = δi +(1 − δi) {(1 − ĜZi(Xi)} with

Although p̂i's are true sampling weights conditional on

, they are correlated with each other unconditionally in finite sample. It is straightforward to see that as the cohort size N → ∞, p̂i − pi → 0 in probability, where pi = δi +(1 − δi) {(1 − ĜZi(Xi)},

, with π(l) (t) = P(Xk ≥t | Zk = zℓ), and

, they are correlated with each other unconditionally in finite sample. It is straightforward to see that as the cohort size N → ∞, p̂i − pi → 0 in probability, where pi = δi +(1 − δi) {(1 − ĜZi(Xi)},

, with π(l) (t) = P(Xk ≥t | Zk = zℓ), and

(l)(t) = E{I (Xk ≤t)δk | Zk = zℓ) Such p̂i was first considered in Samuelsen (1997) under standard NCC sampling, and extended to covariate-matched NCC design in Cai and Zheng (2012). Under the ‘quota’ sampling NCC design, at each selected case's failure time Xj, patients are sequentially sampled from the cohort until m eligible subjects are found. Under a covariate-matched NCC quota sampling design, n(Xj; Zj) is typically unknown, and n*(Xj,Zj), the minimal number of potentially eligible patients ultimately examined in order to obtain the m eligible controls, is recorded instead. Therefore the formulas for calculating p̂i under the classic NCC design (Samuelsen 1997) and the covariate-matched NCC designs (Cai and Zheng 2012) considered previously do not apply for quota sampling.

(l)(t) = E{I (Xk ≤t)δk | Zk = zℓ) Such p̂i was first considered in Samuelsen (1997) under standard NCC sampling, and extended to covariate-matched NCC design in Cai and Zheng (2012). Under the ‘quota’ sampling NCC design, at each selected case's failure time Xj, patients are sequentially sampled from the cohort until m eligible subjects are found. Under a covariate-matched NCC quota sampling design, n(Xj; Zj) is typically unknown, and n*(Xj,Zj), the minimal number of potentially eligible patients ultimately examined in order to obtain the m eligible controls, is recorded instead. Therefore the formulas for calculating p̂i under the classic NCC design (Samuelsen 1997) and the covariate-matched NCC designs (Cai and Zheng 2012) considered previously do not apply for quota sampling.

To construct a consistent estimator of the sampling probability p̂i under quota sampling, denoted by

, we note that quota sampling for the jth case can be viewed as repeated random sampling from a population of size N, consisting of n(Xj,Zj) successes and N − n(Xj,Zj) failures, until m successes were obtained. It follows that conditional on

, n*(Xj,Zj) is a random variable following a negative hypergeometric distribution. A unique maximum likelihood estimate of the rate of success q = n(Xj,Zj)/N is m/n*(Xj,Zj) (Schuster and Sype 1987). This motivates us to obtain

, a replacement for p̂i under quota sampling design, as

, where

, n*(Xj,Zj) is a random variable following a negative hypergeometric distribution. A unique maximum likelihood estimate of the rate of success q = n(Xj,Zj)/N is m/n*(Xj,Zj) (Schuster and Sype 1987). This motivates us to obtain

, a replacement for p̂i under quota sampling design, as

, where

Note that the sampling probability considered in Cai and Zheng (2012) for covariate-matched NCC designs is a ‘true’ sampling probability, since conditional on observed data, n(Xj,Zj) and consequently p̂i are fixed by design. In contrast, is not a true sampling probability, since n(Xj,Zj) is estimated based on the observed n*(tj,Zj), which varies each time a quota sampling is performed. Specific inference procedure is therefore important to account for such variation.

3 Estimation of risk function under a quota NCC sampling design

Inference about the risk function

t(Y) and the accuracy measures under two-phase studies including the quota NCC design can be made through a unified IPW approach with weights for the i subject defined as ŵi = Vi/p̂i, where p̂i can be obtained specifically to accommodate study designs. Our IPW estimators of risk distributions and accuracy measures take the same form but with different choices of ŵi, depending on the study design. For the ease of presentation, we use the generic notation ŵi to denote the weight for the ith subject but note that (i) ŵi = 1 for the full cohort design; (ii) ŵi = Vi/p̂i for the stratified NCC design; and (iii)

for the quota-sampling NCC design.

t(Y) and the accuracy measures under two-phase studies including the quota NCC design can be made through a unified IPW approach with weights for the i subject defined as ŵi = Vi/p̂i, where p̂i can be obtained specifically to accommodate study designs. Our IPW estimators of risk distributions and accuracy measures take the same form but with different choices of ŵi, depending on the study design. For the ease of presentation, we use the generic notation ŵi to denote the weight for the ith subject but note that (i) ŵi = 1 for the full cohort design; (ii) ŵi = Vi/p̂i for the stratified NCC design; and (iii)

for the quota-sampling NCC design.

To estimate

t(Y) under a linear transformation model, Zeng and Lin (2006) previously proposed an efficient non-parametric maximum likelihood likelihood estimator (NPMLE) when there is no missing information on Y. In this paper, we consider an IPW NPMLE procedure to accommodate the various sampling designs. Specifically, under (1), we propose to estimate the unknown model parameters β and H(·) by maximizing an IPW semiparametric likelihood,

t(Y) under a linear transformation model, Zeng and Lin (2006) previously proposed an efficient non-parametric maximum likelihood likelihood estimator (NPMLE) when there is no missing information on Y. In this paper, we consider an IPW NPMLE procedure to accommodate the various sampling designs. Specifically, under (1), we propose to estimate the unknown model parameters β and H(·) by maximizing an IPW semiparametric likelihood,

where Λ1(x) = − log

1(x) and λ1(x) = d Λ1(x)/dx, ΔH(x) = H(x) − H(x−) if H(·) is a step function and ΔH(x) = dH(x)/dx if H(·) is differentiable. It is well known that if the baseline function estimates Ĥ(·) are allowed to be absolutely continuous, the maximizer of the nonparametric likelihood function does not exist, as in the case of density estimation. Thus, following the approaches taken in Murphy et al. (1997) and Zeng and Lin (2006), we estimate H(·) as step functions that jump at the event times {t1,…, tn1} with n1 = Σiδi and hence

. This does not restrict the underlying baseline function H to be discrete. It follows that

1(x) and λ1(x) = d Λ1(x)/dx, ΔH(x) = H(x) − H(x−) if H(·) is a step function and ΔH(x) = dH(x)/dx if H(·) is differentiable. It is well known that if the baseline function estimates Ĥ(·) are allowed to be absolutely continuous, the maximizer of the nonparametric likelihood function does not exist, as in the case of density estimation. Thus, following the approaches taken in Murphy et al. (1997) and Zeng and Lin (2006), we estimate H(·) as step functions that jump at the event times {t1,…, tn1} with n1 = Σiδi and hence

. This does not restrict the underlying baseline function H to be discrete. It follows that

Where

δi(x) − δiλ1(x)− Λ1(x). For any given β,let{ΔĤ(tk; β),k = 1,…,n1} denote the maximizer of ℓ̂ (H,β) with respect to ΔH and

. Then an IPW profile likelihood for β may be obtained as

δi(x) − δiλ1(x)− Λ1(x). For any given β,let{ΔĤ(tk; β),k = 1,…,n1} denote the maximizer of ℓ̂ (H,β) with respect to ΔH and

. Then an IPW profile likelihood for β may be obtained as

An IPW profile likelihood estimator of β0 may be obtained as β̂ = argmaxβl̂profile (β). It follows from the profile likelihood theory (Murphy et al. 1997) and similar arguments given in Zeng and Lin (2006) that β̂ is consistent for β and the estimated baseline function

is uniformly consistent for H(t). Furthermore, one may show that

and

, where

β and

β and

H are the influence functions for β and H under the full cohort design. We note that in the special case of Cox model, β̂ reduces to the same form as the maximum IPW partial likelihood estimator given in Samuelsen (1997), and the baseline cumulative hazard function H estimator is the IPW Bres-low's estimator,

H are the influence functions for β and H under the full cohort design. We note that in the special case of Cox model, β̂ reduces to the same form as the maximum IPW partial likelihood estimator given in Samuelsen (1997), and the baseline cumulative hazard function H estimator is the IPW Bres-low's estimator,

as given in Cai and Zheng (2012). The estimators under these three designs only differ by the use of corresponding weights to account for sampling.

4 Estimation of the predictive capacity of risk markers

4.1 Time-dependent risk distributions

Our estimation goal is to quantify the prediction performance of a vector of markers Y measured at baseline for predicting the time to occurrence of a clinical event, T. Y may include routine clinical risk factors and novel markers such as the recurrence score. In clinical practice, a decision is often made based on a subject's risk of experiencing the event by a future time t based on Y:

t(Y) = P(T < t|Y), rather than on specific values of the multivariate Y. Key summary indices for characterizing the performance of Y are therefore dependent on specifying a risk threshold p for treatment, defined as

t(Y) = P(T < t|Y), rather than on specific values of the multivariate Y. Key summary indices for characterizing the performance of Y are therefore dependent on specifying a risk threshold p for treatment, defined as

Observe that TPRt(p) is one minus the cumulative distribution of risks among those subjects who experience events by time t, and FPRt(p) the corresponding quantity for those who do not. If p = pH defines a threshold above which subjects are considered ‘high risk,’ then TPRt(pH) quantifies the proportion of subjects who have events that are classified as high risk by the model, and FPRt(pH) is the proportion of non-events classified as high risk. For a model with good prediction performance, TPRt(pH) is high and FPRt(pH) is low. In practice one might plot TPRt(p) and FPRt(p) versus the risk threshold level p.

Many recently proposed summaries of prediction performance can be derived based on this pair of risk distributions. The net benefit at time t is a point on the decision curve (Vickers and Elkin 2006; Baker et al. 2009),

. This is a weighted average of TPRt(p) andFPRt(p), where ρt = P(T ≤ t). Pfeiffer and Gail (2011) recently proposed a new set of prediction summaries: the proportion of cases followed (PCF) and the proportion needed to follow-up (PNF) for binary outcomes. To extend their measures to event time data we propose alternatively displaying TPRt(p) against the population risk distribution

t(p) ≡ P[

t(p) ≡ P[

t(Y) ≤ p] or equivalently against

t(Y) ≤ p] or equivalently against

¯t(p) = 1 −

¯t(p) = 1 −

t(p). PCFt(υ) = TPRt{

t(p). PCFt(υ) = TPRt{

¯−1(υ)}, a point on the curve, is the proportion of cases whose risk estimates belong to the top 100υ% of the population; and its inverse function

is the fraction of the general population at the highest risk that needs to be followed to ensure that a fraction p of the cases will be captured. When no specific risk thresholds are of key interest, one may consider summary measures to complement the display of case and control risk distributions. For example,

¯−1(υ)}, a point on the curve, is the proportion of cases whose risk estimates belong to the top 100υ% of the population; and its inverse function

is the fraction of the general population at the highest risk that needs to be followed to ensure that a fraction p of the cases will be captured. When no specific risk thresholds are of key interest, one may consider summary measures to complement the display of case and control risk distributions. For example,

is a time-dependent version of the area under the ROC curve (AUC), which provides a measure of separation between the event and non-event distributions of

t(Y). The area between TPRt(p) and FPRt(p) is equivalent to the difference in mean risks (MRD) between events and non-events, which is related to the IDI statistic for comparing risk models (Pencina et al. 2008),

t(Y). The area between TPRt(p) and FPRt(p) is equivalent to the difference in mean risks (MRD) between events and non-events, which is related to the IDI statistic for comparing risk models (Pencina et al. 2008),

Another summary measure is the difference in proportions of cases and controls above the average risk:

This measure is equal to the popular continuous Net Reclassification (NRI) for comparing a risk model with the null that does not include predictors (in which case all subjects have risk ρt). Interestingly, it has been shown (Gu and Pepe 2009) that ρt(1 − ρt)AARDt is equal to the total gain statistic proposed by Bura and Gast-wirth (2001) for quantifying the predictive capacity of a covariate for a dichotomous outcome. We will consider estimation of these new time-dependent analogues of prediction performance indices that have previously been only considered for the setting of uncensored dichotomous outcomes.

4.2 Comparing risk models

Two models can be compared by calculating summary indices from the pair of risk distributions obtained with each model and then comparing the two corresponding model specific prediction summary indices. Of particular interest is the setting where the old model (‘old’) contains a set of baseline predictors (Yb) and the new model (‘new’) includes these same variables as well as a set of novel markers (Yn). The increment in performance will be of interest and may be summarized with

Another statistic geared specifically toward this setting is the NRI (Pencina et al. 2011), with time-dependent version as

Connection of NRI and IDI with survival outcome is discussed in Uno et al. (2012).

4.3 Estimation of accuracy measures

To estimate points on the risk distribution curves, we consider estimators of TPRt(p) andFPRt(p) as:

| (2) |

| (3) |

Estimators for NBt(p) can be then constructed as . Estimators for PCFt(υ) is

| (4) |

and for PNFt(q) is , where . An estimator for AUCt is , and an estimator for MRDt is , with and . An estimator for AARDt is , where .

5 Inference

Making inference under a NCC design is generally difficult because the sampling scheme leads to weak correlation between the Vi's, which is not ignorable even in large samples. Standard convergence theorems and resampling procedures such as the bootstrap largely require independence assumption and hence cannot be directly applied here. Moreover, sequential quota sampling introduces additional variability into the weights, which must be accounted for.

In Appendix A of the Supplementary Materials available online, we first outline asymptotic expansions for the class of proposed time-dependent measures of prediction performance calculated using data from the full cohort. We require all the regularity conditions listed in the Appendix of Zeng and Lin (2006) for the full cohort design to ensure the validity of our proposed IPW estimators. In addition, we require Gzℓ(t) < 1 for t ∈ (0, τ) so that there is a positive probability for all non-cases to be sampled into the subochort, where [0, τ] is the support of C.

For a generic shorthand

representing either TPRt, FPRt, NBt(p), PCFt, PNFt, AUCt,MRDt, or AARDt, the processes

, is asymptotically equivalent to a sum of independent and identically distributed (i.i.d) terms,

, where U

representing either TPRt, FPRt, NBt(p), PCFt, PNFt, AUCt,MRDt, or AARDt, the processes

, is asymptotically equivalent to a sum of independent and identically distributed (i.i.d) terms,

, where U i (·) is defined in Appendix A for each of the summary measures. Similarly, we can show that the processes

, is asymptotically equivalent to a sum of independent and identically distributed (i.i.d) terms,

, where

. By the functional central limit theorem (Pollard 1990) it can be shown that the process

i (·) is defined in Appendix A for each of the summary measures. Similarly, we can show that the processes

, is asymptotically equivalent to a sum of independent and identically distributed (i.i.d) terms,

, where

. By the functional central limit theorem (Pollard 1990) it can be shown that the process

(·) and

(·) and

Δ

Δ

(·) converges weakly to mean zero Gaussian processes with a variance function

and

respectively.

(·) converges weakly to mean zero Gaussian processes with a variance function

and

respectively.

In Appendix B of the Supplementary Material, we show that under a quota NCC sampling scheme for the corresponding IPW estimators

QNCC with

, which is asymptotically normal with mean 0 and variance

QNCC with

, which is asymptotically normal with mean 0 and variance

| (5) |

where pi is the limiting value of p̂i, and with Z taking L possible unique values {z1,…zL},

l = P(Zi = zl),

and

are defined in Appendix B. In practice to obtain an estimator of

, we may replace all theoretical quantities in Equation 5 with their counterparts from estimated realizations.

l = P(Zi = zl),

and

are defined in Appendix B. In practice to obtain an estimator of

, we may replace all theoretical quantities in Equation 5 with their counterparts from estimated realizations.

We note that under a covariate-matched NCC sampling, the corresponding estimators , is asymptotically normal with mean 0 and variance

| (6) |

where π(l)(t) = P(Xk ≥ t | Zk = zl) (Cai and Zheng 2012). Therefore, comparing to , it is apparent that quota sampling will always be less efficient than classic NCC sampling, due to the need to adjust for variation in the quota sampling weights. However, in settings with rare events, π(l)(t) is close to 1 at the observed event times, hence the loss of efficiency will be minimal.

6 Simulation

We conducted simulation studies to examine the performances of our proposed procedures with practical sample sizes. We considered a scenario where controls were matched with cases on a binary covariate Z, in addition to matching on the event time. With a cohort of size 2,000, we first generated Y and Z̃ from a standard bivariate normal distribution, where Y and Z̃ had a correlation of 0.5. We then generated a binary Z such that Z=1 if Z̃ > 0. The event time T was generated conditioning on Y from a linear transformation model with P(T > t|Y) = J0{log(0.1 t) + βY}, with J0(x) = exp{− exp(x)}, and β = log(3). The censoring time C was taken to be the minimum of 2 and W, where W follows a gamma distribution, with a shape parameter of 2.5 and a rate parameter of 2. This yielded approximately 87 % censoring and a mean number of cases of 266 over 2,000 repeated datasets. For those with observed failure times, we randomly selected m controls individually matched to the time at which the case is observed to have an event and shared the same value of Z as the case. To mimic a NCC quota sampling scenario as in the breast cancer study example, for each selected case, we randomly ordered all subjects in the cohort and then sequentially went through the cohort ascertaining eligibility and follow-up information until the m controls are found. In both designs we considered m = 1 and 3. The total number of individuals searched was recorded for each matching set. We then calculated the time-dependent measures of prediction performance defined in Sect. 2 setting t = 1. Results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of simulation studies of estimates under cohort, NCC and quota sampling NCC (QNCC) designs.

| True | Cohort | NCC | QNCC | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nmatch 1=1 | nmatch 1=3 | nmatch 1=1 | nmatch 1=3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Est. | SD | SE | Cov. | Est. | SD | SE | Cov. | Est. | SD | SE | Cov. | Est. | SD | SE | Cov. | Est. | SD | SE | Cov. | ||

| TPRt(0.25) | 0.479 | 0.478 | 0.035 | 0.034 | 0.938 | 0.481 | 0.047 | 0.048 | 0.944 | 0.479 | 0.039 | 0.039 | 0.951 | 0.479 | 0.049 | 0.049 | 0.947 | 0.478 | 0.04 | 0.039 | 0.948 |

| FPRt(0.25) | 0.115 | 0.115 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.947 | 0.116 | 0.018 | 0.019 | 0.96 | 0.115 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.942 | 0.115 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.948 | 0.115 | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.935 |

| PCFt,(0.2) | 0.531 | 0.532 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.951 | 0.535 | 0.028 | 0.028 | 0.946 | 0.533 | 0.022 | 0.023 | 0.954 | 0.535 | 0.028 | 0.029 | 0.95 | 0.532 | 0.022 | 0.023 | 0.957 |

| PNFt(0.85) | 0.475 | 0.476 | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.944 | 0.474 | 0.031 | 0.027 | 0.9 | 0.475 | 0.024 | 0.022 | 0.924 | 0.474 | 0.03 | 0.027 | 0.923 | 0.475 | 0.024 | 0.022 | 0.922 |

| AUCt | 0.789 | 0.788 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.944 | 0.784 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.941 | 0.787 | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.953 | 0.785 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.948 | 0.786 | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.959 |

Mean(

t|T ≤ t) t|T ≤ t) |

0.293 | 0.295 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.938 | 0.296 | 0.026 | 0.026 | 0.95 | 0.295 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.948 | 0.294 | 0.026 | 0.026 | 0.953 | 0.294 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.95 |

Mean(

t|T > t) t|T > t) |

0.121 | 0.119 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.941 | 0.119 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.962 | 0.119 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.948 | 0.118 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.938 | 0.119 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.936 |

| MRD | 0.172 | 0.176 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.938 | 0.177 | 0.027 | 0.027 | 0.941 | 0.176 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.948 | 0.176 | 0.027 | 0.027 | 0.951 | 0.175 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.952 |

| TPRt(ρ) | 0.704 | 0.705 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.94 | 0.704 | 0.023 | 0.022 | 0.939 | 0.705 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.948 | 0.705 | 0.024 | 0.023 | 0.94 | 0.705 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.948 |

| FPRt(ρ) | 0.278 | 0.278 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.944 | 0.277 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.947 | 0.278 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.953 | 0.278 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.947 | 0.278 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.955 |

| AARDt | 0.426 | 0.427 | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.946 | 0.428 | 0.03 | 0.029 | 0.943 | 0.427 | 0.023 | 0.024 | 0.951 | 0.428 | 0.029 | 0.029 | 0.946 | 0.427 | 0.023 | 0.024 | 0.956 |

| NBt(p) | 0.062 | 0.062 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.948 | 0.063 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.963 | 0.062 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.947 | 0.062 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.945 | 0.062 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.944 |

The NCC designs also match controls to cases on a binary covariate Z.

Est. mean estimates, SD empirical standard deviation, SE average of the estimated standard error, CP empirical coverage level of the 95 % confidence intervals for proposed estimators

Across all three designs, all estimators are unbiased, the standard errors appear to perform well, and coverage of nominal 95% intervals is close to 95%. Standard errors from quota sampling are only slightly larger than their counterparts for the standard NCC sampling in a few cases, suggesting that efficiency lost due to quota sampling is negligible and probably can be ignored in practice. We only present results for FPRt(p) with p = 0.25, representing a risk level sufficiently higher than the average risk of 0.145, however we also observed good performance of TPRt(p) and FPRt(p) at lower level of risk (e.g., p = 0.1) (result not shown). Similar results are also found in situations where matching is only on the event time (results not shown). Table 2 shows that our IPW estimators are in general more efficient than estimators in which Λ(t|Y) is estimated by the method used in Habel et al. (2006) (‘Langholz estimator’).

Table 2. Summary of simulation studies for predictive performance estimates under cohort, matched NCC and quota Sampling NCC (QNCC) designs using the Langholz estimator for

t(Y).

t(Y).

| True | NCC | QNCC | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nmatch=1 | nmatch=3 | nmatch=1 | nmatch=3 | ||||||||||

| Est. | SD | RE | Est. | SD | RE | Est. | SD | RE | Est. | SD | RE | ||

| TPRt(p) = 0.25) | 0.479 | 0.483 | 0.079 | 2.8 | 0.479 | 0.055 | 1.983 | 0.48 | 0.079 | 2.623 | 0.479 | 0.056 | 1.978 |

| FPRt(p) = 0.25) | 0.115 | 0.115 | 0.022 | 1.464 | 0.115 | 0.017 | 1.276 | 0.115 | 0.024 | 1.434 | 0.115 | 0.017 | 1.231 |

| PCFKt(0.2) | 0.531 | 0.535 | 0.039 | 1.96 | 0.533 | 0.028 | 1.547 | 0.534 | 0.038 | 1.76 | 0.533 | 0.028 | 1.573 |

| PNFt(0.85) | 0.475 | 0.475 | 0.043 | 1.989 | 0.476 | 0.03 | 1.613 | 0.474 | 0.042 | 1.806 | 0.475 | 0.031 | 1.656 |

| AUCt | 0.789 | 0.785 | 0.027 | 2.441 | 0.787 | 0.019 | 1.83 | 0.785 | 0.026 | 2.283 | 0.787 | 0.019 | 1.908 |

Mean(

t|T ≤ t) t|T ≤ t) |

0.293 | 0.3 | 0.047 | 3.354 | 0.296 | 0.032 | 2.21 | 0.298 | 0.047 | 3.183 | 0.296 | 0.033 | 2.22 |

Mean(

t|T > t) t|T > t) |

0.121 | 0.119 | 0.009 | 1.123 | 0.119 | 0.008 | 1.075 | 0.119 | 0.01 | 1.121 | 0.119 | 0.008 | 1.052 |

| MRDt | 0.172 | 0.181 | 0.047 | 3.002 | 0.177 | 0.031 | 2.098 | 0.179 | 0.045 | 2.9 | 0.177 | 0.032 | 2.163 |

| TPRt(ρ) | 0.704 | 0.706 | 0.028 | 1.473 | 0.705 | 0.019 | 1.394 | 0.706 | 0.028 | 1.414 | 0.705 | 0.019 | 1.392 |

| FPRt(ρ) | 0.278 | 0.276 | 0.03 | 1.709 | 0.278 | 0.02 | 1.481 | 0.278 | 0.029 | 1.598 | 0.278 | 0.02 | 1.524 |

| AARDt | 0.426 | 0.43 | 0.046 | 2.408 | 0.428 | 0.031 | 1.812 | 0.428 | 0.044 | 2.277 | 0.427 | 0.032 | 1.876 |

| NBt(p) | 0.062 | 0.064 | 0.015 | 3.071 | 0.063 | 0.01 | 1.899 | 0.064 | 0.016 | 2.713 | 0.063 | 0.011 | 1.834 |

Est. mean estimates, SD empirical standard deviation, RE the relative efficiency of the estimates compared to the IPW estimator

We also conducted another set of simulations to evaluate the performance of proposed estimators for comparing the performance between two risk models similarly to the practical situation considered in the Example Section next. Two predictors Y1 and Y2 were simulated from a bivariate standard normal distribution and a correlation of.5. Two models are considered for validation and comparison. Model 1, based on a model score Snew = log(3)Y1 + log(2)Y2, and Model 2, based on a model score Sold = Y1. The event time T was generated from a model with P(T > t|Y) = J0{log(0.1t) + Snew}, with

0(x) = exp{−exp(x)} and censoring time C was generated the same way as the first set of simulations. All cases from the 2,000 cohort members are selected. For each case, 3 individually matched controls are selected using the quota sampling design. The differences in the predictive performance indices between the two models and the corresponding standard errors were calculated over 2,000 datasets. The results presented in Table 3 indicate that our proposed point and interval estimators for comparing model scores are valid, providing both unbiased estimates and adequate 95 % coverage probability.

0(x) = exp{−exp(x)} and censoring time C was generated the same way as the first set of simulations. All cases from the 2,000 cohort members are selected. For each case, 3 individually matched controls are selected using the quota sampling design. The differences in the predictive performance indices between the two models and the corresponding standard errors were calculated over 2,000 datasets. The results presented in Table 3 indicate that our proposed point and interval estimators for comparing model scores are valid, providing both unbiased estimates and adequate 95 % coverage probability.

Table 3. Simulation results for comparing the differences in predictive performance of two prediction models under quota sampling NCC (QNCC) designs.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 − Model 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | SE | Est. | SE | True | Est. | SE | SD | Cov. | |

| TPRt(0.25) | 0.686 | 0.022 | 0.644 | 0.025 | 0.041 | 0.042 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.944 |

| FPRt(0.25) | 0.148 | 0.014 | 0.161 | 0.015 | −0.011 | −0.013 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.947 |

| PCF(0.2) | 0.614 | 0.018 | 0.569 | 0.019 | 0.045 | 0.045 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.928 |

| PNFt(0.85) | 0.58 | 0.019 | 0.527 | 0.019 | 0.05 | 0.053 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.933 |

| AUCt | 0.859 | 0.009 | 0.83 | 0.011 | 0.027 | 0.029 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.920 |

Mean(

t|T ≤ t) t|T ≤ t) |

0.767 | 0.012 | 0.739 | 0.013 | 0.024 | 0.028 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.933 |

Mean (

t|T > t) t|T > t) |

0.215 | 0.012 | 0.24 | 0.013 | −0.024 | −0.025 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.948 |

| MRDt | 0.552 | 0.018 | 0.499 | 0.019 | 0.047 | 0.053 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.912 |

| TPRt(ρ) | 0.46 | 0.02 | 0.411 | 0.021 | 0.051 | 0.05 | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.938 |

| FPRt(ρ) | 0.124 | 0.007 | 0.136 | 0.008 | −0.011 | −0.012 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.945 |

| AARDt | 0.336 | 0.022 | 0.275 | 0.022 | 0.063 | 0.061 | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.937 |

| NBt(p) | 0.116 | 0.009 | 0.108 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.946 |

Est. mean estimates, SD empirical standard deviation, SE average of the estimated standard error, CP empirical coverage level of the 95 % confidence intervals for proposed estimators

7 Example

The Framingham risk model (Wilson et al. 1998), based on common clinical risk factors, is used for population-wide cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk assessment. A new risk model, based on variables in the Framingham risk model and an inflammation marker, C-reactive protein (CRP), has been developed using data from the Women's Health Study (Cook et al. 2006). In order to decide whether routine screening of CRP levels is warranted, it is important to quantify the prediction performance of the new model, especially in comparison to that of the existing model. We illustrate here how our proposed procedure can be used to evaluate and compare the clinical utility of the two risk models using an independent dataset from the Framingham Offspring Study (Kannel et al. 1979).

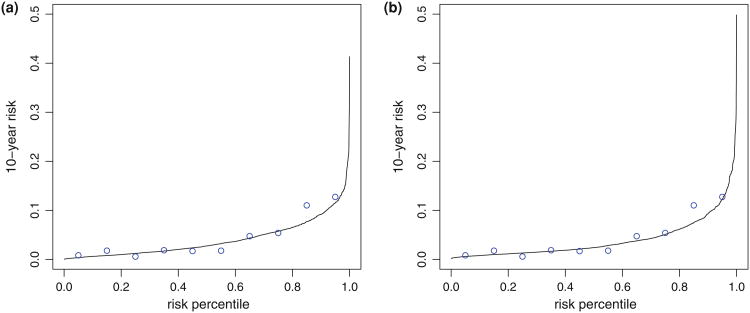

The Framingham Offspring Study was established in 1971 with 5,124 participants who were monitored prospectively for epidemiological and genetic risk factors for CVD. We consider here 1,728 female participants who have CRP measurement and other clinical information at the second exam and are free of CVD at the time of examination. The average age of this subset was about 44 years (SD = 10). The outcome we considered is the time from exam date to first major CVD event including CVD related death. During the follow-up period 269 participants were observed to encounter at least one CVD event and the 10-year event rate was about 4%. Since all subjects have CRP data in this cohort, the Framingham data allows us to illustrate the methods with a real dataset, examining both a full cohort design and different NCC sampling designs with the same dataset. For each individual, two risk scores were calculated: one based on the Framingham risk model (Model 1), combining information on age, systolic blood pressure, smoking status, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), total cholesterol, and medication for hypertension; the other model was based on an algorithm developed in Cook et al. (2006) (Model 2), with the addition of CRP concentration. We used Cox models to specify the relation between the event time and model scores (linear predictors from the models). Figure 1 shows that both models were well calibrated. For subgroups categorized according to deciles, their average predicted 10-year risks matched well with Kaplan–Meier estimators of 10-year risks in the subgroups. Since our interest is in predicting 10-year CVD risk (i.e., t = 10 years), we defined cases as individuals who experienced an event by 10 years after the measurement of clinical risk factors and CRP, and controls as individuals who did not. We then calculated the time-dependent prediction performance measures defined in Sect. 2 for each risk model, and evaluated the increment in performance for Model 2 over Model 1 in terms of these measures. The calculations were based on data from (1) all eligible women in the cohort; (2) NCC datasets assembled by sampling 3 time-matched controls using the classic NCC sampling scheme; (3) NCC datasets using a quota sampling scheme.

Fig. 1.

Calibration of two risk models for predicting the risk of experiencing a CVD event within 10 years. Each figure shows modelbased estimates of 10-year CVD risk versus distribution of the risk at 10 year (solid lines) and empirical estimates of 10-year risks for subgroups categorized according to deciles of risk distribution (circles). Figure (a) based on the Framingham risk model and Figure (b) based a risk model with CRP added in the prediction model

In Table 4, we present estimates of the predictive indices for both risk models along with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) based on the three sampling methods. We see that if individuals whose 10-year CVD risk in the top 20% are to be followed, the new model would capture 54.2 % of the cases [PCF(0.20) = 54.2 %, 95% CI = (49%, 59.2 %)). Conversely, in order to capture 15% of cases by 10 years, the new risk model suggest that 47.2 % of the population needs to be followed (PNF(.85) = 47.2%, 95%CI of (41.6, 52.9%)]. Other indices for gauging the predictive performance also suggest the new model is quite predictive. For example, the average 10-year risk among events is 0.086 (95%CI= (0.062, 0.110)), which is substantially higher than the estimated 10-year prevelance of 0.040. The mean risk is slightly higher than that observed among controls (0.038), and resulted in MRD10years = 0.048, (95%CI= (0.030, 0.067)). We used the summary indices as the basis for hypothesis tests to formally compare the predictive capacities of the two models. The differences between estimates of the indices were calculated, and a CI for the difference excluding 0 will indicate a significant difference. We see that differences between the new model and the Framingham risk model are not statistically significant, no matter what summary index is employed. The predictive performance can also be visualized by plotting risk distributions for cases and controls separately (Fig. 2).

Table 4. Estimates (Est.) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of prediction indices based on two risk models used for predict 10-year CVD risk among women in the Framingham offspring cohort.

| Cohort | NCC | QNCC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | CI | Est. | CI | Est. | CI | |

| Model 1 | ||||||

| TPRt(p = 0.15) | 0.083 | (0.001, 0.165) | 0.076 | (0.025, 0.128) | 0.069 | (−0.005, 0.143) |

| FPRt(p = 0.15) | 0.014 | (−0.002, 0.030) | 0.013 | (0.004, 0.021) | 0.011 | (−0.004, 0.026) |

| PCFt(0.2) | 0.510 | (0.458, 0.562) | 0.502 | (0.431, 0.573) | 0.503 | (0.443, 0.562) |

| PNFt(0.85) | 0.483 | (0.427, 0.538) | 0.478 | (0.411, 0.545) | 0.466 | (0.406, 0.526) |

| AUCt | 0.752 | (0.721, 0.783) | 0.747 | (0.705, 0.789) | 0.744 | (0.708, 0.780) |

Mean(

t|T ≤ t) t|T ≤ t) |

0.077 | (0.055, 0.099) | 0.074 | (0.050, 0.097) | 0.075 | (0.052, 0.097) |

Mean(

t|T > t) t|T > t) |

0.039 | (0.030, 0.047) | 0.039 | (0.030, 0.048) | 0.039 | (0.030, 0.048) |

| MRDt | 0.039 | (0.023, 0.055) | 0.035 | (0.017, 0.054) | 0.036 | (0.020, 0.053) |

| TPR;(ρ) | 0.734 | (0.704, 0.764) | 0.742 | (0.703, 0.782) | 0.718 | (0.679, 0.757) |

| FPR;(ρ) | 0.359 | (0.333, 0.385) | 0.371 | (0.332, 0.411) | 0.353 | (0.320, 0.386) |

| AARDt | 0.375 | (0.326, 0.425) | 0.371 | (0.304, 0.438) | 0.365 | (0.306, 0.424) |

| NBt(p) | 0.015 | (0.008, 0.023) | 0.015 | (0.007, 0.023) | 0.015 | (0.007, 0.023) |

| Model 2 | ||||||

| TPRt(p = 0.15) | 0.155 | (0.061, 0.248) | 0.083 | (−0.034, 0.201) | 0.131 | (0.066, 0.196) |

| FPRt(p = 0.15) | 0.024 | (0.007, 0.042) | 0.014 | (−0.010, 0.038) | 0.021 | (0.011, 0.032) |

| PCFt(0.2) | 0.542 | (0.493, 0.592) | 0.553 | (0.487, 0.619) | 0.521 | (0.461, 0.581) |

| PNFt(0.85) | 0.472 | (0.416, 0.529) | 0.499 | (0.437, 0.561) | 0.442 | (0.385, 0.499) |

| AUCt | 0.758 | (0.729, 0.787) | 0.768 | (0.730, 0.805) | 0.743 | (0.708, 0.779) |

Mean(

t|T ≤ t) t|T ≤ t) |

0.086 | (0.062, 0.110) | 0.088 | (0.059, 0.117) | 0.080 | (0.056, 0.104) |

Mean(

t|T > t) t|T > t) |

0.038 | (0.029, 0.047) | 0.038 | (0.029, 0.046) | 0.038 | (0.029, 0.047) |

| MRDt | 0.048 | (0.030, 0.067) | 0.051 | (0.026, 0.075) | 0.042 | (0.023, 0.060) |

| TPR;(ρ) | 0.696 | (0.669, 0.723) | 0.722 | (0.687, 0.758) | 0.683 | (0.645, 0.720) |

| FPR;(ρ) | 0.310 | (0.282, 0.338) | 0.318 | (0.280, 0.356) | 0.318 | (0.284, 0.351) |

| AARDt | 0.386 | (0.338, 0.434) | 0.404 | (0.343, 0.465) | 0.365 | (0.307, 0.424) |

| NBt(p) | 0.016 | (0.009, 0.023) | 0.016 | (0.009, 0.024) | 0.015 | (0.008, 0.022) |

| Model 2-Model 1 | ||||||

| TPRt(p = 0.15) | 0.071 | (−0.045, 0.188) | 0.051 | (−0.101, 0.203) | 0.062 | (−0.031, 0.154) |

| FPRt(p = 0.15) | 0.011 | (−0.012, 0.033) | 0.008 | (−0.022, 0.039) | 0.011 | (−0.006, 0.028) |

| PCFt(0.2) | 0.032 | (−0.034, 0.098) | 0.051 | (−0.044, 0.146) | 0.018 | (−0.054, 0.091) |

| PNFt(0.85) | −0.010 | (−0.083, 0.063) | 0.021 | (−0.070, 0.112) | −0.024 | (−0.092, 0.044) |

| AUCt | 0.006 | (−0.033, 0.046) | 0.021 | (−0.035, 0.077) | 0.000 | (−0.044, 0.044) |

Mean(

t|T ≤ t) t|T ≤ t) |

0.009 | (−0.023, 0.041) | 0.014 | (−0.022, 0.051) | 0.005 | (−0.028, 0.039) |

Mean(

t|T > t) t|T > t) |

−0.001 | (−0.013, 0.012) | −0.001 | (−0.013, 0.011) | 0.000 | (−0.013, 0.012) |

| MRDt | 0.010 | (−0.014, 0.033) | 0.015 | (−0.015, 0.046) | 0.006 | (−0.019, 0.031) |

| TPR;(ρ) | −0.038 | (−0.073, −0.004) | −0.020 | (−0.070, 0.030) | -0.035 | (−0.076, 0.005) |

| FPR;(ρ) | −0.049 | (−0.082, −0.016) | −0.053 | (−0.102, −0.004) | −0.035 | (−0.073, 0.003) |

| AARDt | 0.011 | (−0.052, 0.074) | 0.033 | (−0.057, 0.123) | 0.000 | (−0.070, 0.070) |

| NBt(p) | 0.000 | (−0.010, 0.011) | 0.001 | (−0.009, 0.012) | 0.000 | (−0.011, 0.010) |

Estimates are obtained under cohort, NCC and quota sampling NCC (QNCC) designs

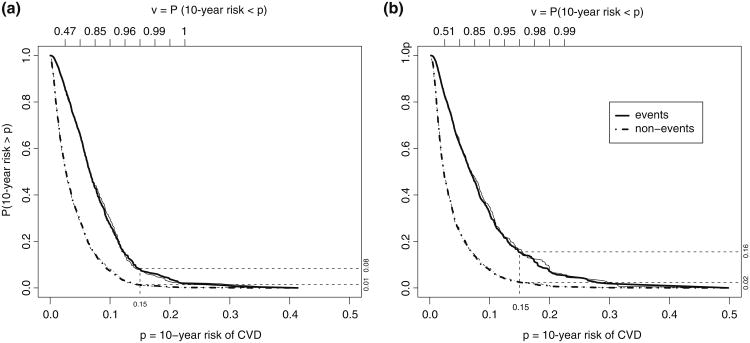

Fig. 2.

Distributions of risk based on two models for predicting the risk of experiencing a CVD event within 10 years. Figure (a) based on the Framingham risk model and Figure (b) based a risk model with CRP added in the prediction model. Distributions are shown separately for subjects who had an events in 10-years (Events, solid lines) and for subjects who did not (non-Events, dashed lines). Thick lines: estimates from full cohort. Thin lines: estimates based on all cases and their matched controls sampled with a NCC quota sampling method

The point estimates from both NCC designs are quite close to those from the full cohort for most of the measures with a single NCC sample from the cohort. The curves estimated from data obtained with the quota sampling design (averaging over 50 repeated assembled sets) essentially overlap those obtained with the full cohort in Fig. 2. For interval estimates, with a sample size 48.6% of the full cohort, CIs from both the NCC designs in a few cases are wider compared with estimates from the full cohort. However they all lead to the same conclusion that observed incremental values of the new model over the conventional Framingham model is not significant. Confidence intervals from the quota NCC sample are comparable to those of the classic NCC sample, with about 62 % of the records in the cohort being reviewed in order to find 3 time-matched controls for each case.

8 Discussion

A wide variety of summary measures are in use in practice to evaluate risk prediction models but methods for estimating them have been mainly developed for binary outcome data (Cui 2009; Lloyd-Jones 2010). The additional dimension of time is important to capture the time-varying nature in risk prediction. One contribution of this manuscript is to provide tools for estimating the distributions of risk for the population or for cases and controls. This extends previous work for binary data (Gu and Pepe 2009) to outcomes that are event times subject to right censoring.

Adopting cost-effective two-phase designs for validation of risk markers is of great practical importance, especially for diseases with low prevalence rates. In practice a cohort with complete follow-up and clinical data is rarely available. The classic NCC designs require first that follow-up and clinical data be ascertained for all subjects in the cohort and then subjects with and without events are identified for assaying the risk marker. The quota NCC design, sequentially ascertaining current follow-up information and clinical data pertaining to inclusion criteria for subjects in a cohort, is practically very appealing and is done frequently in practice. However there has been no statistical procedure for data collected under these practical designs in the context of evaluating biomarker performance. Our research here is a step towards filling that gap. We focused here on a general class of semiparametric models and made inference about the accuracy measures based on the model. Extending the estimation procedure to more flexible nonparametric procedures for assessing prediction performance would also be of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Framingham Heart Study and the Framingham SHARe project are conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with Boston University. The Framingham SHARe data used for the analyses described in this manuscript were obtained through dbGaP (Access No.: phs000007.v3.p2). This manuscript was not prepared in collaboration with investigators of the Framingham Heart Study and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the Framingham Heart Study, Boston University, or the NHLBI. The work is supported by Grants U01-CA86368, P01-CA053996, R01- GM085047, R01-GM079330, U54 LM008748 and R01HL089778 awarded by the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material: The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10985-013-92708) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Yingye Zheng, Email: yzheng@fhcrc.org, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1100 Fairview Avenue North, Seattle, WA 98109, USA.

Tianxi Cai, Department of Biostatistics, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Margaret S. Pepe, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1100 Fairview Avenue North, Seattle, WA 98109, USA

References

- Andersen P, Gill R. Cox's regression model for counting processes: a large sample study. Ann Stat. 1982;10(4):1100–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Baker S, Cook N, Vickers A, Kramer B. Using relative utility curves to evaluate risk prediction. J R Stat Soc Ser A. 2009;172(4):729–748. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2009.00592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgan Ø, Goldstein L, Langholz B. Methods for the analysis of sampled cohort data in the cox proportional hazards model. Ann Stat. 1995;23:1749–1778. [Google Scholar]

- Bura E, Gastwirth J. The binary regression quantile plot: assessing the importance of predictors in binary regression visually. Biom J. 2001;43(1):5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Cai T, Zheng Y. Evaluating prognostic accuracy of biomarkers under nested case–control studies. Biostatistics. 2012;13(1):89–100. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxr021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S, Wei L, Ying Z. Analysis of transformation models with censored data. Biometrika. 1995;82(4):835–845. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S, Wei L, Ying Z. Predicting survival probabilities with semiparametric transformation models. J Am Stat Assoc. 1997;92(437):227–235. [Google Scholar]

- Cook N. Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction. Circulation. 2007;115(7):928–935. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.672402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook N, Buring J, Ridker P. The effect of including c-reactive protein in cardiovascular risk prediction models for women. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(1):21–29. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-1-200607040-00128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox D. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1972;84:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Cui J. Overview of risk prediction models in cardiovascular disease research. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19(10):711–717. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein L, Langholz B. Asymptotic theory for nested case–control sampling in the Cox regression model. Ann Stat. 1992;20(4):1903–1928. [Google Scholar]

- Gu W, Pepe M. Measures to summarize and compare the predictive capacity of markers. Int J Biostat. 2009;5(1):27. doi: 10.2202/1557-4679.1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habel L, Shak S, Jacobs M, Capra A, Alexander C, Pho M, Baker J, Walker M, Watson D, Hackett J, et al. A population-based study of tumor gene expression and risk of breast cancer death among lymph node-negative patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8(3):R25. doi: 10.1186/bcr1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannel W, Feinleib M, McNamara P, Garrison R, Castelli W. An investigation of coronary heart disease in families. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;110(3):281–290. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langholz B, Borgan Y. Estimation of absolute risk from nested case-control data. Biometrics. 1997;53:767–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Jones D. Cardiovascular risk prediction: basic concepts, current status, and future directions. Circulation. 2010;121(15):1768–1777. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.849166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy S, Rossini A, Van der Vaart A. Maximum likelihood estimation in the proportional odds model. J Am Stat Assoc. 1997;92:968–976. [Google Scholar]

- Pencina M, D'Agostino R, Sr, D'Agostino R., Jr Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27(2):157–172. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pencina M, D'Agostino R., Sr Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Stat Med. 2011;30(1):11–21. doi: 10.1002/sim.4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe M, Feng Z, Huang Y, Longton G, Prentice R, Thompson I, Zheng Y. Integrating the predictiveness of a marker with its performance as a classifier. Am J Epidemiol. 2008a;167(3):362–368. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe M, Feng Z, Janes H, Bossuyt P, Potter J. Pivotal evaluation of the accuracy of a biomarker used for classification or prediction: standards for study design. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008b;100(20):1432–1438. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettitt A. Proportional odds models for survival data and estimates using ranks. Appl Stat. 1984;1:169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer R, Gail M. Two criteria for evaluating risk prediction models. Biometrics. 2011;67(3):1057–1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2010.01523.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard D. Empirical processes: theory and applications. Institute of Mathematical Statistics 1990 [Google Scholar]

- Prentice R. A case–cohort design for epidemiologic cohort studies and disease prevention trials. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Rundle A, Vineis P, Ahsan H. Design options for molecular epidemiology research within cohort studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(8):1899–1907. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelsen SO. A pseudolikelihood approach to analysis of nested case–control studies. Biometrika. 1997;84:379–394. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster E, Sype W. On the negative hypergeometric distribution. Int J Math Educ Sci Technol. 1987;18(3):453–459. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DC. Addendumto“Methodsofcohortanalysis:Appraisalbyapplicationtoasbestos mining”. J R Stat Soc Ser A. 1977;140:483–485. [Google Scholar]

- Uno H, Tian L, Cai T, Kohane I, Wei L. A unified inference procedure for a class of measures to assess improvement in risk prediction systems with survival data. Early view online, Statistics in Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1002/sim.5647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickers A, Elkin E. Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med Decis Making. 2006;26(6):565–574. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06295361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson P, D'Agostino R, Levy D, Belanger A, Silbershatz H, Kannel W. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97(18):1837–1847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng D, Lin D. Efficient estimation of semiparametric transformation models for counting processes. Biometrika. 2006;93:627–640. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.