Abstract

Aldehyde-deformylating oxygenase (ADO) catalyzes O2-dependent release of the terminal carbon of a biological substrate, octadecanal, to yield formate and heptadecane in a reaction that requires external reducing equivalents. We show here that ADO also catalyzes incorporation of an oxygen atom from O2 into the alkane product to yield alcohol and aldehyde products. Oxygenation of the alkane product is much more pronounced with C9-10 aldehyde substrates, so that use of nonanal as the substrate yields similar amounts of octane, octanal, and octanol products. When using doubly-labeled [1,2-13C]-octanal as the substrate, the heptane, heptanal and heptanol products each contained a single 13C-label in the C-1 carbons atoms. The only one-carbon product identified was formate. [18O]-O2 incorporation studies demonstrated formation of [18O]-alcohol product, but rapid solvent exchange prevented similar determination for the aldehyde product. Addition of [1-13C]-nonanol with decanal as the substrate at the outset of the reaction resulted in formation of [1-13C]-nonanal. No 13C-product was formed in the absence of decanal. ADO contains an oxygen-bridged dinuclear iron cluster. The observation of alcohol and aldehyde products derived from the initially formed alkane product suggests a reactive species similar to that formed by methane monooxygenase (MMO) and other members of the bacterial multicomponent monooxygenase family. Accordingly, characterization by EPR and Mössbauer spectroscopies shows that the electronic structure of the ADO cluster is similar, but not identical, to that of MMO hydroxylase component. In particular, the two irons of ADO reside in nearly identical environments in both the oxidized and fully reduced states, whereas those of MMOH show distinct differences. These favorable characteristics of the iron sites allow a comprehensive determination of the spin Hamiltonian parameters describing the electronic state of the diferrous cluster for the first time for any biological system. The nature of the diiron cluster and the newly recognized products from ADO catalysis hold implications for the mechanism of C-C bond cleavage.

Keywords: biofuel, non-heme diiron enzyme, oxygenase, 13C-NMR, GC/MS, Prochlorococcus marinus, EPR, Mössbauer

1. INTRODUCTION

Bacterial synthesis of diesel-length alkanes and alkenes expands the biofuel inventory beyond alcohols and esters1-4 by making a source of renewable, drop-in, liquid fuels.5-10 Recently, a two-gene cluster required for alkane/alkene biosynthesis was identified in cyanobacteria.11 The hydrocarbons formed had an odd chain length (C13, C15 and C17), indicating they were biosynthesized by removal of the C-1 carbon of even chain-length fatty acyl groups. In this biosynthetic pathway, the fatty acyl group is reduced by an acyl-ACP reductase, a member of the short-chain dehydrogenase family, to produce the corresponding aldehyde. The second enzyme in the pathway, a dinuclear iron cluster-containing enzyme, removes the aldehydic carbon to produce a hydrocarbon. Initially the displaced single-carbon product was proposed to be carbon monoxide based on previous reports on similar reactions observed in whole cells and cell extracts of plants and animals.11,12 More recently, formate was shown to be the co-product of the hydrocarbon-generating enzyme with the second oxygen atom derived from atmospheric dioxygen.13,14 In light of this, the hydrocarbon-generating enzyme has been given the name aldehyde-deformylating oxygenase (ADO).15

The amino acid sequence of ADO reveals similarity to a number of enzymes that utilize a dinuclear iron cluster to activate O2 for oxygenation or oxidation reactions including ribonucleotide reductase (RNR-R2), methane monooxygenase (MMO), a tRNA-modifying enzyme, MiaE, Δ9-fatty acid desaturase and toluene monooxygenases.16-25 In addition, the X-ray crystal structure of ADO shows that it has a dimetal center with coordination similar to that found for these enzymes.11 Each of these enzymes employs an oxygen-activation strategy whereby the reduced enzyme binds dioxygen and subsequently carries out an oxidation reaction. In this context, it is interesting that the ADO reaction is redox neutral overall. In fact, this led to a proposal that ADO does not require dioxygen and that the oxygen atom in the formate product derives from water.26 However, a reexamination of the data showed that an oxygenolytic mechanism is operative.15,27

The mechanism of O2 activation and product formation of ADO remains unknown. Mechanisms involving FeIIIFeIII-superoxo,28 FeIIIFeIII-μ-peroxo29,30 as well as high valent FeIIIFeIV-μ-oxo31 and FeIVFeIV-bis-μ-oxo32-34 species have been proposed for other oxygen activating enzymes in the dinuclear iron cluster family. These species are known to catalyze numerous types of reactions such as hydrocarbon oxygenation, alcohol and aldehyde oxidation, epoxidation, and desaturation as well as radical formation.32,34

Here, we have characterized the metal cluster of ADO for comparison with those found in other oxygen activating diiron cluster-containing enzymes. A study of the products formed during reaction of ADO with both a biological substrate octadecanal and shorter hydrocarbon aldehydes was conducted. Surprisingly, it is found that, in addition to the well documented formate and (n-1) alkane products, ADO catalyzes formation of products in which oxygen from O2 is incorporated to form (n-1) alcohols and aldehydes. These newly recognized products give insight into the nature of the ADO reaction and the reactive species generated during catalysis.

2. EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

2.1 Chemicals and Reagents

All reagents, solvents, standards and enzymes were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich with the following exceptions heptadecanal, octadecanal (TCI America, Portland, OR), nonanal (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA), and [13C]- formaldehyde (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, MA). Methods for syntheses of 13C-labeled aldehydes are presented in the Supporting Information (SI).

2.2 Aldehyde-Deformylating Oxygenase Purification

Prochlorococcus marinus ADO (NP_895059) was expressed in BL21(DE3) with an N-terminal histidine-tag from an E. coli-codon optimized gene (DNA2.0, Menlo Park, CA) in pET28b. To increase iron content of ADO, cells were grown in terrific broth and induced at 25 °C with 0.2 mM IPTG (U. of Minnesota Biotechnology Resource Center production batch WAC110911). ADO was purified in 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5 by ion exchange chromatography on a DEAE column using a linear gradient of 0-400 mM NaCl. Purified protein was desalted by dialysis against 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.5. The percent iron incorporation varied with each purification from 40% to 80%.

2.3 ADO Reactions and GC/MS/FID analysis

Reactions were typically carried out in 300 μl reaction volumes in 2 mL GC vials at room temperature for 30 minutes unless otherwise noted. 30 μM ADO, 500 μM aldehyde substrate in ethyl acetate (1% v/v final), 100 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 75 μM phenazine methyosulfate (PMS) and 2 mM NADH. When noted, spinach ferredoxin (100 μg/mL), ferredoxin reductase (0.1 U/mL) and NADPH (2 mM) were substituted for PMS and NADH. Dodecane standard was added to 45 μM and reactions were extracted with 300 μL methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE). The organic layer was assayed using a gas chromatograph (GC) with an HP-1ms column (100% dimethylsiloxane capillary; 30 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm), a helium gas flow of 1.75 ml/min, and 250 °C injection port. The sample was split at the column outlet between a flame ionization detector HP 7890A (Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, CA) and a mass spectrometer HP 5975C (GC/MS/FID). For octanal, nonanal, decanal and undecanal the oven was held at 45 °C for 5 minutes, ramped to 60 °C at 5 degrees per minute, then ramped to 320 °C at 30 degrees per minute. For dodecanal, the oven temperature was held at 60 °C for 5 minutes, ramped to 150 °C at 10 degrees per minute, then ramped to 320 °C at 20 degrees per minute. For octadecanal, the oven was ramped from 100 to 320 °C at 10 °C per minute. All programs included a 5 minute hold at 320 °C. Concentrations of products were determined using the equation of the best fit line for the plot of MS peak area for aldehyde, alkane or alcohol ranging from 5 to 250 μM. Peaks were identified by comparison of retention times and mass spectra to authentic standards.

2.4 ADO Reaction in [18O]-O2

After reaction mixtures were degassed with alternating argon and vacuum on a Schlenk line to remove 16O2, they were exposed to [18O]-O2 under slight positive pressure. The reactions were started with degassed NADH and allowed to proceed for 10 minutes. Six Ng/mL degassed alcohol dehydrogenase was added and the reactions were incubated for an additional 10 minutes before extraction, bis(trimethylsilyl)acetamide derivatization (1% final in organic layer) and GC/MS/FID analysis as described above. The abundance of the oxygen-containing m+/z ions at 187 through 191 was determined.

2.5 [1-13C]-1-Nonanol Addition to Decanal ADO Reaction

[1-13C]-1-Nonanol was synthesized from [1-13C]-nonanoic acid with borane-tetrahydrofuran using the methods of Kende and Fludzinski.35 1-Nonanol or [1-13C]-1-nonanol was added to a standard ADO reaction to 0.5 mM or 1.5 mM with 200 μM decanal and PMS/NADH. Percent 13C-incorporation was calculated as percent m+ +1/z signal of the total signal from a fragmentation ion pair (m+/z + m+ +1/z). The reported values are an average of three measurements each for the three major electron impact fragment ions which retain the labeled carbon.36

2.6 13C-NMR

Using a 7001 Megatron, 700 MHz Bruker NMR, spectra were collected using standard parameters for protein decoupled 13C-NMR data with 24,000 transients. The ADO reaction consisted of 3 mM [1-13C]-nonanal, 3 mM ADO, 50 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.4, 0.1 mg/mL spinach ferredoxin, 0.1 U/mL ferredoxin reductase, 2 mM NADPH, 1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 10% D2O.

2.7 Mössbauer and EPR Methods

Methods for Mössbauer and EPR spectroscopies are presented in SI.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Novel Products of ADO Reaction Consistent with an Oxygenase Reaction

ADO reaction mixtures containing octadecanal and a reducing system (NADH/phenazine) were extracted and analyzed by liquid GC/MS. Heptadecane, an alkane one-carbon shorter than the substrate, was observed as previously reported.11,13,37 In addition to heptadecane, we also observed heptadecanal that accounted for less than 3% of the heptadecane yield. Heptadecane and heptadecanal peaks on the GC/MS chromatogram were validated by comparison of the retention time and mass spectral fragmentation pattern to those of authentic standards. Incomplete control reactions without enzyme or without NADH lacked both this new aldehyde product and the previously observed alkane product.

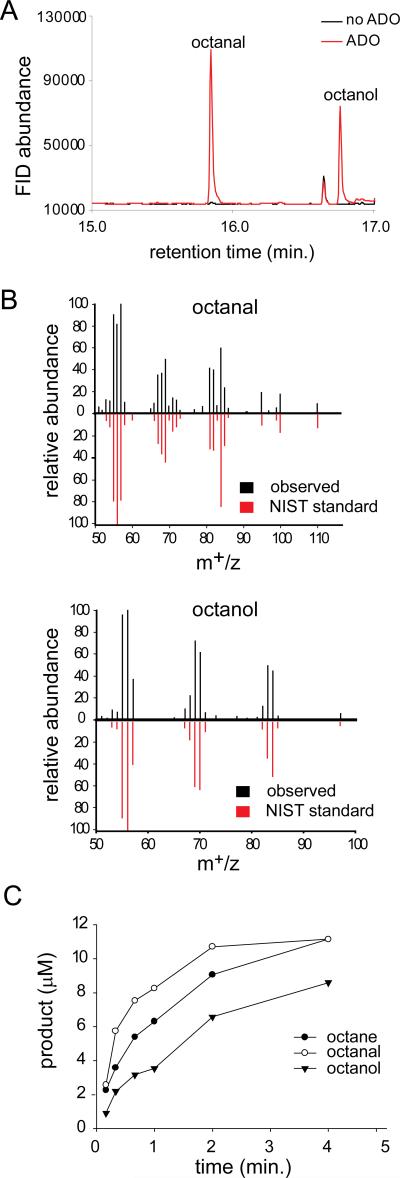

The production of heptadecanal indicated that ADO enzyme was capable of incorporating O2 into a methylene carbon, and thus the reaction mixture was also tested for the presence of an alcohol product (heptadecanol). The high boiling point of the long chain heptadecanol complicates GC analysis, so reactions with shorter-chain aldehyde substrates were examined. Rather than sampling the reaction headspace, which would favor the detection of volatile alkane products, liquid GC/MS was again used to analyze the organic layer of extracted ADO reactions. Using nonanal as the substrate, octane, octanal and octanol were observed (Figure 1). Peak identification was confirmed by comparison of retention time and mass spectra to authentic standards. Furthermore, a small amount of heptane was also observed and the time course of heptanal formation is consistent with octanal being a precursor (Figure S1).

Figure 1.

A) GC/Flame Ionization Detector (FID) chromatogram of ADO reaction with nonanal. B) Mass spectra of octanal and octanol from GC/MS analysis (black) compared to mass spectra from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) database (red). C) Time dependence of product formation in ADO reaction with nonanal.

ADO was reacted with aldehydes of varied chain-lengths to determine the effect of chain-length on product formation. The formation of the additional products is a general feature of the ADO reaction. However, the relative yields of aldehyde and alcohol products varied significantly with the chain-length of the aldehyde substrate (Table 1 and Figure S2). In a separate experiment, replicate reactions of 30 μM ADO with octanal or nonanal (500 μM) and NADH/phenazine were quenched at two minutes. Products were determined by GC/MS (Table 1). A marked decrease in relative yields of aldehyde and alcohol products were observed as the alkyl chain-length was decreased from C9 to C8. Investigation of a range of aldehydes revealed that relative yields of the one-carbon shorter alcohol and aldehyde products was optimum with nonanal and decanal and decreased with shorter and longer alkyl chains.

Table 1.

Alkyl-Products of 30 uM ADO Reactions.

| Substrate | Alkane | Aldehyde | Alcohol |

|---|---|---|---|

| octanal | 16 ± 10a | < 5 | < 5 |

| nonanal | 16 ± 9 | 17 ± 5 | 10 ± 7 |

product concentrations (μM) of two minute reactions with NADH/phenazine in triplicate ± standard deviation.

Because the NADH/phenazine/O2 turnover system could afford the production of reactive oxygen species, control reactions were performed in which spinach ferredoxin, spinach ferredoxin reductase and NADPH were substituted for the NADH/phenazine reduction system. The additional aldehyde and alcohol products were still observed, suggesting that they represent enzyme catalyzed products (Figure S3). Furthermore, in the absence of NAD(P)H or enzyme, no products are observed with either the ferredoxin or phenazine systems.

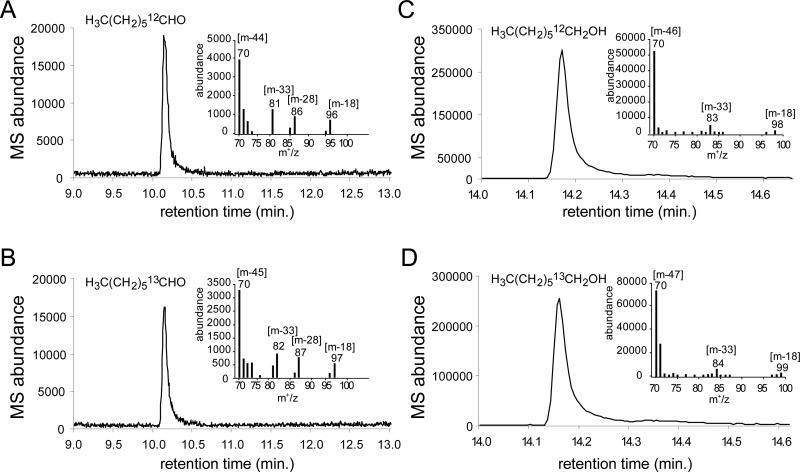

Further experiments were conducted to confirm that the observed novel products were not contaminants. First, the incubation of aldehyde substrates with an increasing concentration of enzyme yielded an increased rate of production of all three one-carbon shortened products, alkane, alcohol and aldehyde, as well as the two-carbon shorter alkane. Second, in light of the recent finding that catalase greatly increases ADO reaction turnover by removing the inhibitory H2O2 produced by the inefficient coupling of the reduction system to the enzyme,38 a control ADO reaction in the presence of catalase (1 mg/mL) was also analyzed. The one-carbon shortened alcohol and aldehyde products could be detected in the presence of catalase. Lastly, to definitely confirm that the observed products were derived from the substrate aldehyde, [1,2-13C]-octanal was synthesized. The purity was analyzed by NMR (Figure S4). The double labeled aldehyde was used as an ADO substrate. Upon reaction, products resulting from removal of the [13C]-labeled aldehydic carbon from the double-labeled aldehyde substrate would retain one [13C]-atom, distinguishing products from any unlabeled contaminating aldehydes or alcohols. In a complete reaction mixture with [1,2-13C]-octanal, the heptane, heptanal, and 1-heptanol products could be detected by GC-MS as expected (Figures 2 and S5). MS analysis was consistent with the presence of a single 13C-label on the new C1 of the products, revealing that the oxygenated products are derived from [1,2-13C]-octanal. Electron ionization-mass spectrometry (EI-MS) produced the signature fragmentation pattern for the aldehyde and alcohol products, yielding ions that result from dehydration [m-18], elimination of ethylene [m-28] and dehydration with terminal demethylation [m-33].36

Figure 2.

GC/MS spectra of heptanal (A,B) and 1-heptanol (C,D) products of ADO reaction with unlabeled octanal (A,C) and [1,2-13C]-octanal (B,D). EI-MS fragmentation patterns are inset with the mass of major fragments indicated.

3.2 Single-Carbon Reaction Co-products

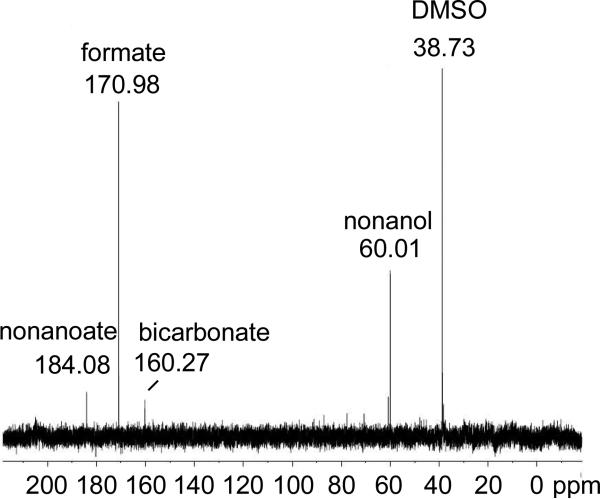

In light of these prominent oxygenated reaction products with C8-C10 aldehydes, we considered that other one-carbon products might also form. Since nonanal produced high relative yields of the alcohol and aldehyde products (Table 1), experiments were conducted using [1-13C]-nonanal and 13C-NMR to analyze co-products. The phenazine reducing system was shown to cause minor oxidation of formaldehyde to formate in preliminary experiments, and thus the ferredoxin reducing system was used in these experiments. Following the reaction, [13C]-formate was readily apparent in the 13C-NMR spectrum (Figure 3). Another single-carbon compound, [13C]-bicarbonate, appeared at substoichiometric levels over the course of a long overnight acquisition. The low level of bicarbonate detected is consistent with it arising from a partial oxidation of formic acid. Additional peaks were identified as [1-13C]-1-nonanol and [1-13C]-nonanoic acid, both detected in the aldehyde preparation (Figure S6), and DMSO, a reaction additive. An observed peak at 60.81 ppm was not identified.

Figure 3.

13C-NMR of ADO reaction mixture with [1-13C]-nonanal.

Notably, formaldehyde, carbon monoxide and methanol were not detected by 13C-NMR. The 13C-NMR chemical shifts of [13C]-formaldehyde, [13C]-methanol and [13C]-carbon monoxide are 84.5, 51.6 and 181.3 ppm, respectively, as reported by the University of Wisconsin Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank. Further experiments mitigated against the production of other products. [13C]-Formaldehyde was not identified using an HPLC-MS assay for formaldehyde derivatized with Nash reagent39 that was shown with standards to readily detect 30 NM formaldehyde (Table S1). Carbon monoxide was looked for in ADO reaction mixtures incubated in sealed cuvettes. After reacting, reduced myoglobin was injected into each cuvette and visible spectrum was analyzed for the characteristic absorbance of myoglobin-CO at 425nm. Based on the minimal spectral change, we can infer that CO, if formed, would account for less than-1% of the co-product formed. (Figure S7). Other experiments using [1-13C]-octanal as the substrate yielded [13C]-formate, as expected.

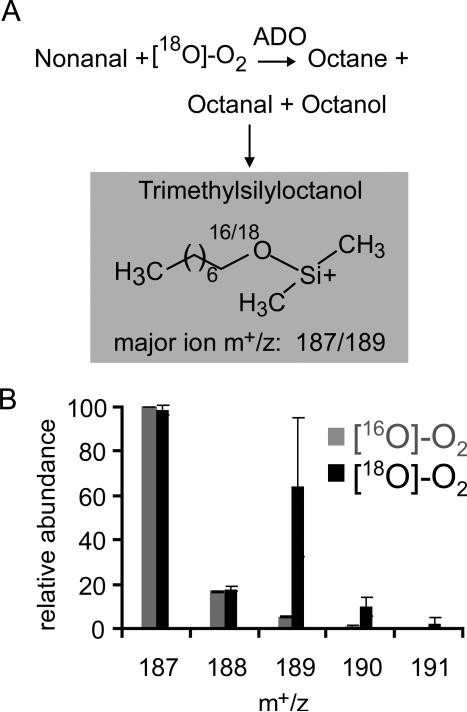

3.3 Oxygen Incorporation into Alcohol and Aldehyde Products

Before conducting experiments with [18O]-O2, we first confirmed that the formation of all of the reaction products depended on the presence of oxygen. While oxygen levels can be reduced to less than 10 ppm in an anaerobic chamber, if the ADO has a low Km for oxygen, as has been suggested, some ADO activity would still be expected even after degassing in an anaerobic chamber.15,27,38 To further deplete oxygen, reactions were run in an anaerobic chamber following preincubation with homoprotocatechuate 2,3 dioxygenase from Brevibacterium fuscum40 and homoprotocatechuate (HPCA) as an oxygen scavenging system. Under these conditions, using dodecanal as a substrate, the amount of undecane detected was comparable to control reactions lacking NADH (Figure S8). Accordingly, no undecanal or undecanol could be detected in these reaction mixtures. These data are consistent with recent findings and strongly support a strict oxygen requirement for the ADO reaction, including the novel product species identified in the present study.38

To follow oxygen-18 incorporation during the ADO reaction, a reaction with ADO and nonanal was conducted under an [18O]-O2 atmosphere at pH 7.4. The reaction mixture at 10 minutes was treated with an excess of equine alcohol dehydrogenase and NADH to reduce any remaining aldehyde and prevent further exchange. Any octanol thus produced, in addition to the ADO product octanol, was derivatized with bis(trimethylsilyl)acetamide and analyzed by GC/MS (Figure 4A). The derivatized alcohol product contained substantial levels of 18O (Figure 4B) in the major m+/z ion (187). The major ion corresponds to the loss of one methyl group from the trimethylsilyl adduct. The mass spectrum derived from the sample exposed to 16O2 showed the expected ratio of n, n+1, and n+2 m+/z ions owing to the natural abundance of 13C-atoms (Figure 4B). The mass spectrum of the reaction product obtained under [18O]-O2 clearly exhibits an n+2 ion at m+/z of 189 with a concomitant shift of the isotopic pattern by two mass units. It was calculated from triplicate data that the oxygen incorporation into the products from [18O]-O2 was 36% ±12%. Based on the product ratios previously determined (Table 1), octanol accounted for 37% of the oxygenated products. Thus, the data suggested nearly complete exchange of the aldehyde 18O with solvent during the 10 minute incubation period, consistent with recent exchange measurements by Li et al. 201215 and essentially complete incorporation of 18O from [18O]-O2 into the product octanol.

Figure 4.

(A) ADO Reaction scheme with [18O]-O2 using alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) to convert octanal to octanol followed by derivatization with bis(trimethylsilyl)acetamide. The major ion of trimethylsilyloctanol is shown. (B) Relative abundance of the major ion (187) and isotopes of trimethylsilyloctanol. Error bars indicate standard deviation of triplicate analysis.

3.4 Reaction of ADO with Product Alcohol

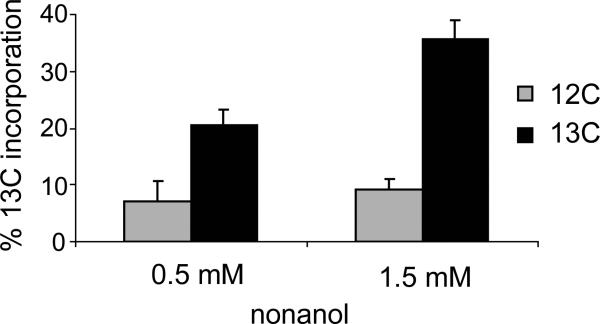

The observation of 18O-labeled oxygen incorporation into the alcohol product of the ADO reaction with nonanal solidified the identification of ADO as an oxygenase. Diiron oxygenases like MMO that form hydroxylated products are often able to both react with hydrocarbons to form alcohol adducts and also oxidize the alcohol products to aldehydes.41 In the case of ADO, addition of nonane or nonanol to the complete reaction mixture in the absence of decanal failed to yield any oxygenated or oxidized products. However, after addition of excess [1-13C]-1-nonanol to an ADO reaction with decanal, [1-13C]-nonanal was observed by GC/MS (Figure 5). (As expected, unlabeled nonane product was observed, while the nonanol product detection was obscured by [1-13C]-1-nonanol addition.) The percent incorporation of 13C from the [1-13C]-1-nonanol was calculated to be 14 and 26% for 0.5 mM and 1.5 mM added [1-13C]-1-nonanol, respectively, after correction for natural abundance 13C in the [12C]-1-nonanol control. At 1.5 mM, the added nonanol exceeded the solubility limit in water (~ 1 mM); therefore, the two-fold increase in percent label incorporation from 0.5 mM to 1.5 mM added [1-13C]-1-nonanol is consistent with a two fold increase in soluble nonanol.

Figure 5.

13C-Incorporation into nonanal product. 13C-Labeled (black) and unlabeled nonanol (gray) were added at 0.5 mM and 1.5 mM to a complete ADO reaction with 200 NM decanal. Error bars indicate standard deviation of a triplicate analysis.

Although it appears that aldehyde products can react with ADO to undergo deformylation with formation of an (n-1) alkane, we could find no evidence for enzyme-dependent oxidation of the product aldehydes to form acid adducts. It is also clear from the results shown in Figure 5 that the decanal substrate does not prevent formation of the aldehyde product from the 13C-labeled product alcohol. Finally, the total yield of (n-1) products is not increased by addition of 13C labeled product alcohol.

3.5 Mössbauer and EPR Characterization of ADO

The observation of alcohol and aldehyde products that apparently derive from an intermediate alkane product suggests that the reactive diiron cluster of ADO is capable of catalyzing other types of chemistry than deformylation of aldehydes. Alkane hydroxylation with incorporation of oxygen from [18O]-O2 is the hallmark reaction of the diiron containing soluble form of MMO and related enzymes from the bacterial multicomponent monooxygenase (BMM) family. Past studies have employed EPR, Mössbauer, and other spectroscopies to provide detailed characterizations of BMM family enzymes.42-51 Mössbauer spectroscopy, more so than any other single technique, can furnish detailed information about the electronic structure of the diferrous state of diiron(II) proteins. Spectra recorded in applied magnetic fields are rich in information, and this information can be used to assess the electronic structure and reactivity of the protein under study and compare it with corresponding properties of related proteins. The spectra of proteins such as MMO hydroxylase component (MMOH)42,52 and RNR-R253 are immensely complex and comprehensive fits of the Mössbauer spectra, yielding a set of spin Hamiltonian parameters, have not yet been reported. Fortunately, the spectra of diferrous ADO, while still complex, have some encouraging features (reflecting good structural homogeneity) which allowed us to obtain the first complete set of spin Hamiltonian parameters. The ADO data analysis, presented below, has yielded insights that will allow us to succeed in fitting the data of diiron enzymes such as MMOH and RNR-R2 in the future, thereby providing a detailed comparison of the electronic structure of the diiron centers in these proteins.

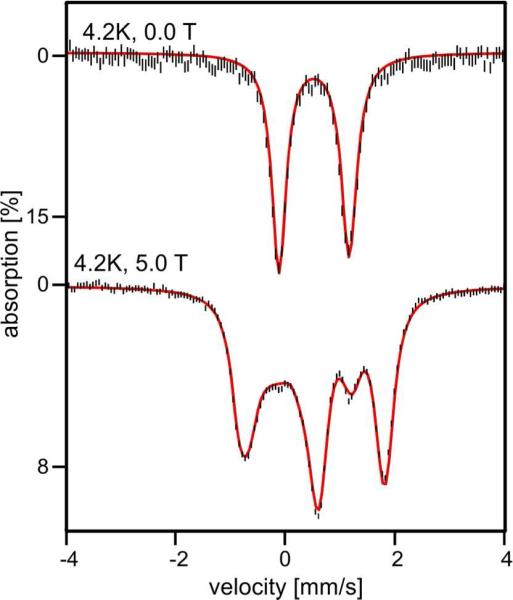

3.5.1 Diferric ADO

Figure 6 top shows a Mössbauer spectrum of “as isolated” ADO recorded at 4.2 K in the absence of an applied magnetic field (B = 0). The spectrum consists of a doublet that is slightly asymmetric with a quadrupole splitting EQ = 1.27 mm/s and isomer shift δ = 0.52 mm/s. It is possible to represent the spectrum equally well as a superposition of two doublets with ΔEQ(1) = 1.30 mm/s and ΔEQ(2) = 1.24 mm/s that may differ in δ by 0.01 mm/s, using Lorentzian lines with of 0.31 mm/s full width at half maximum, but we doubt whether such a representation is more meaningful than the one for one doublet (comment: the sample was quite concentrated. It had an iron concentration of ca. 3.5 mM, which leads to some line broadening due to thickness effects). An applied field B = 5.0 T (Figure 6, bottom) elicits a pattern characteristic of a system with a diamagnetic (S = 0) ground state, as is typically observed for antiferromagnetically coupled diiron clusters with high-spin FeIII sites. The observation of one doublet, or two differing slightly in ΔEQ, suggests that both iron sites of ADO have a fairly similar, possibly identical, ligand environment. For diferric MMOH we have found ΔEQ = 1.05 mm/s and δ = 0.51 mm/s (identical sites) for one preparation52 ΔEQ(1) = 1.16 mm/s, ΔEQ(2) = 0.87 mm/s and δ(1,2) ≈ 0.51 for a two site fit in a later preparation.

Figure 6.

4.2 K Mössbauer spectra of diferric ADO recorded in zero-field (top) and in a field of 5.0 T applied parallel to the observed γ radiation (bottom). The red lines are spectral simulations for a species with S = 0 assuming two equivalent Fe sites with ΔEQ = 1.27 mm/s, η = 0.41 and δ = 0.52 mm/s. Sign (ΔEQ) was determined from fitting the 8.0 T spectrum.

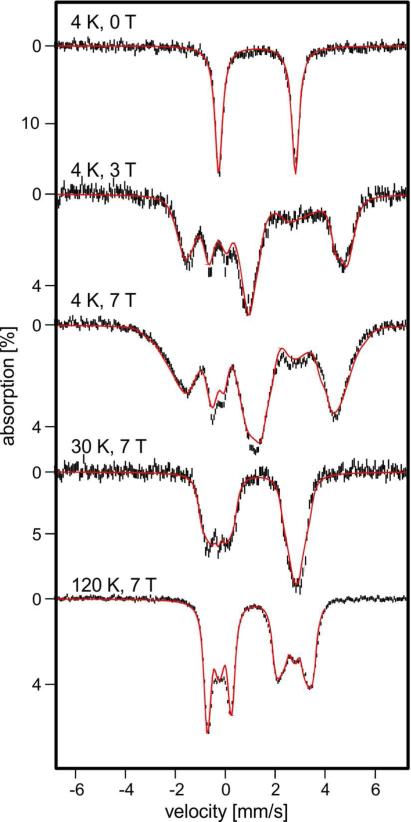

3.5.2 Diferrous ADO

After anaerobic addition of sodium dithionite to the sample of Figure 6, a Mössbauer spectrum (Figure 7, top) was observed with ΔEQ = 3.10(4) mm/s and δ = 1.30(2) mm/s in zero-magnetic field. These parameters are characteristic of high-spin FeII sites, and they are close to those reported for other diiron(II) enzymes such as MMOH, toluene 4-monooxygenase, and RNR-R2.25,32,42,54 The observation of a single doublet suggests that for the diferrous state, just as for the diferric one, the two FeII sites are quite similar. Mössbauer spectra of high-spin FeII complexes recorded in variable applied magnetic fields yield intricate spectral patterns from which detailed fine structure and hyperfine structure parameters can be extracted. These spectra, however, depend on numerous parameters (as many as 20 for a diiron protein even if all tensors share the same principal axes frame), and because of this complication, a complete set of parameters has not yet been reported for any diiron(II) protein. However, well resolved spectra, rich in detail, of reduced ADO allowed us to obtain such a set of parameters.

Figure 7.

Variable field, variable temperature Mössbauer spectra of diferrous ADO (conditions indicated in figure). Spectra were recorded in magnetic fields applied parallel to the observed γ radiation. The red lines represent spectral simulations based on eqs 1-4 using the parameters listed in Table 2. The spectra were simulated using the 2Spin routine of WMOSS. Additional spectra are shown in Figure S9.

The interactions relevant for a combined Mössbauer and EPR study of diferrous ADO are the zero-field splittings (ZFS), electronic Zeeman, magnetic hyperfine, nuclear Zeeman, and quadrupole interactions of the two Fe sites. We also require a term, Ĥexch = JŜ1 · Ŝ2, that describes exchange interactions between the two sites with electronic spin S1 = S2 = 2. For ADO, as for MMOH,42 the exchange coupling is quite small, namely |J| < 0.5 cm−1, and ferromagnetic (J < 0); see below. In the ensuing sections, it will be useful to employ a spin Hamiltonian that can conveniently be evaluated and discussed in the weak coupling limit, i.e. under conditions for which |J| << zero-field splittings.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where the index i = 1,2 labels the two sites. Furthermore, in eq 2, D1, E1 and D2, E2 are the tetragonal and rhombic zero-field splitting parameters of site 1 and 2, respectively, and g1 and g2 are the electronic g-tensors. A1 and A2 are the 57Fe magnetic hyperfine tensors and ĤQ(i = 1,2) describes the interactions of the nuclear quadrupole moment Q with the electric field gradient (EFG) tensor (principal components VXX, VYY and VZZ); η = (VXX – VYY)/VZZ is the asymmetry parameter. Our analysis indicates that the ZFS, g- and A-tensors of both Fe sites share a common principal axis system (x, y, z) and that the principal axes of the two EFGs (X, Y, Z) are rotated with respect to (x, y, z). While all parameters of eqs 1-4 are accessible by Mössbauer spectroscopy, only eq 2 is required for the EPR results. In order to simplify the presentation of a rather complex exchange coupled system, we state at the outset a result obtained after a series of Mössbauer simulations: namely, the parameters of the two sites of ADO differ only in a minor way and, within our resolution, the tensors of both sites have the same spatial orientation. For simplicity, we will use a double label when the quantities are the same for both sites, e.g. (E/D)1,2 stands for (E/D)1 = (E/D)2.

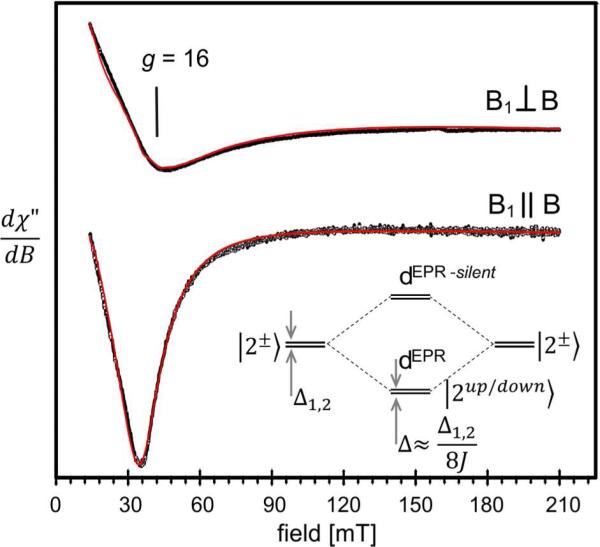

Figure 8 shows low temperature X-band EPR spectra of diferrous ADO recorded at T = 3 K with a bimodal cavity operated in parallel (bottom) and transverse (top) modes. A prominent signal at g = 16 is seen in both modes. A transverse mode spectrum for diferrous ADO with a resonance at g = 13 was previously reported by Marsh and coworkers;37 however, spectral simulations were not presented. Since the spectra of Figure 8 are similar to those analyzed by Hendrich and coworkers for reduced MMOH,43 we mention here only the principal features of the electronic system as described by eq 2. Figure S10, which leans on Figure 4 of Hendrich et al. 1990,43 will aid the reader in the following discussion; the insert in Figure 8 separately depicts the lowest four spin levels.

Figure 8.

X-band EPR spectra of diferrous ADO. The red traces are simulations based on eq 2 using D1,2 = −6.6 cm−1, E/D1,2 = 0.21, σ(E/D)1,2 = 0.0176; gx 1,2 = gy 1,2 = 2.0, gz 1,2 = 2.15, Jx,y,z = −0.253 cm−1 and packet width = 10 mT. Experimental conditions: T = 3 K; 9.408 GHz in parallel mode and 9.646 GHz in transverse mode; 1 mW microwave power, modulation 1 mT. For comments on spin-spin dipolar interactions see SI. The insert shows the lowest four spin levels of the coupled diferrous state.

The observed EPR signal originates from transitions between the levels of a quasi-degenerate ground doublet with an energy gap Δ (for B = 0). For the doublet considered here the resonance condition can be written as described in Hendrich et al. 1990:43

| (5) |

where ν is the microwave frequency, α the angle between B and the molecular z axis and geff ≈ 4(g1z + g2z) = 8gz ≈ 16 with gz = (g1z + g2z)/2. Briefly, the EPR-active doublet reflects the following situation. The ZFS parameters D1 and D2 of the two iron sites of reduced ADO are negative, indicating that for each site the ground state is a spin doublet of m1 = ± 2 or m2 = ± 2 parentage, where m1 and m2 are the magnetic quantum numbers. In Figure 8, which shows the lowest four spin levels, as well as in Figure S10, these states are labeled |2±>. In the absence of exchange interactions a second-order perturbation treatment yields for the spin doublet of each site a splitting Δi = 3(E/D)i2Di. For a mononuclear FeII such quasi-degenerate doublets frequently yield a Δm = 0 EPR transition near geff(1,2) = 4g(1,2)z ≈ 8. However, in the case of weak exchange coupling between the two sites, the two |2±> ground doublets combine to produce two new doublets, which we labeled as dEPR and dEPR-silent in Figures 8 and S10. For ferromagnetic coupling dEPR is the ground doublet; its two levels are split by Δ ≈ Δ1Δ2/8|J| (or Δ ≈ Δ1,2/8|J| for equivalent sites).43 The expression for Δ is approximate and serves to guide the reader; for our analysis we have used the exact solutions to eqs 1-4. This doublet is EPR-active at X-band while dEPR-silent, at an energy ε ≈ 8J, is essential diamagnetic and EPR-silent. Diferrous ADO has a very small J value. Theoretically, the sign of J can be determined by studying the temperature dependence of the EPR-signal below ≈ 6 K. However, such measurements are difficult to perform with the widely available EPR flow cryostats. The sign of J can be unambiguously determined from the low temperature Mössbauer spectra: we demonstrate by means of the spectra of Figure S9 that the coupling is ferromagnetic and that dEPR is the ground state.

As argued in SI, the z components of the 57Fe A-tensors obtained from Mössbauer spectroscopy can be used to constrain g1z and g2z to 2.0 ≤ gz1,2 ≤ 2.15, a condition which allowed us to determine Δ of eq 5 by simulating the EPR spectra of Figure 8. A good representation of the EPR line shape was obtained by assuming that the rhombicity parameters (E/D)1,2 have a Gaussian distribution around a mean (E/D)1,2 = 0.21 with σ(E/D)1,2 = 0.017. The red lines in Figure 8 are (SpinCount) simulations based on the parameters listed in the caption. The simulation for the coupled system was obtained for Δ = 0.31 cm−1 and g1z = g2z = 2.15. Note that the EPR signal depends on Δ (and geff) and only indirectly on (E/D)i, Di and J; the latter quantities can be obtained from Mössbauer spectroscopy.42

We have recorded Mössbauer spectra of diferrous ADO between 4.2 K and 160 K in applied magnetic fields up to 8.0 T. Here we list some relevant observations; detailed comments can be found in SI. The presence of an EPR-active ground doublet, dEPR, with a small splitting,55 implies that the 4.2 K Mössbauer spectra exhibit paramagnetic hyperfine structure even in moderate applied fields (mixing of the two levels, |2up> and |2down>, by the applied magnetic field is proportional to gzβB/Δ). Indeed, small applied fields B induce in ADO sizable magnetic hyperfine fields, Bint,z(i) at the 57Fe nuclei (i=1,2) along the molecular z direction (see the 0.3 T spectra of Figure S12), given by Bint,z(i) =−<Szi>Azi/gnβn. The expectation value <Sz,i> = <2down|Sz,i|2down> of the electron spin operator, determined by eq 2, reaches saturation for B ≈ 1.5 T (Figure S11), assuming the value <Sz> ≈ −2 for the <2down>, the only level significantly populated at 4.2 K for B ≥ 1 T. Furthermore, for B > 1.5 T the system is essentially decoupled, i.e. at these fields for the spectral simulations of the 4.2 K spectra one can set J = 0 and treat the spectra as if they were originating from two independent FeII sites. Our simulations for B > 2.0 T yield Az1/gnβn = −6.5 T and Az2/gnβn = −8.0 T. Az1 and Az2 are the only parameters for which we found noticeable differences between the two sites. Between T = 25 K and 50 K, in the regime of fast relaxation of the electronic spins, the spectra are fairly sensitive to the zero-field splitting parameters D1,2; our simulations suggest that −7 cm−1 < D1,2 < −5 cm−1. Above 100 K the magnetic hyperfine field Bint,i = −<Si>th•Ai/gnβn is only marginally dependent of the ZFS parameters (<Si>th is the expectation value of S averaged over all thermally accessible spin levels).55 Under these conditions we established the sign of ΔEQ, η, and a good estimate for the A-tensor components. This is discussed in greater detail in SI. Finally, and significantly, the 0.3 T Mössbauer spectra of Figure S12 show that the EPR active spin doublet with splitting Δ is the ground state; hence J < 0. With this information, and taking the EPR constraint Δ ≈ 0.31 cm−1 into account we have simulated the spectra for the whole data set by least-squares fitting groups of spectra. These efforts yielded the parameters listed in Table 2 and the theoretical curves (red lines) of Figures 7 and S8. The simulations are not perfect, but given the complexity of the system the simulations shown in Figures 7 and S8 represent the data quite well over a wide range of temperature and applied fields.

Table 2.

Fine structure and hyperfine structure parameters of diferrous ADO derived from the analysis of the Mössbauer spectra using eq 1-4.

| ja [cm−1] | Db [cm−1] | eid | g x,y,z | Ax,y,z/gnβn [T]c | δ [mm/s] | ΔEQd [mm/s] | n d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.2 | −6.6(10) | 0.21(3) | 2.00, 2.00, 2.15 | −25(5),−22(3),−6.5/−8.0 | 1.30(2) | 3.10(4) | 0.7(2) |

Spin-spin dipolar interactions between the two FeII spins may be comparable with the exchange term. Only the z-components of these interactions matter (see SI). The quoted j may thus be Jeff,z = Jz + Jzspin-dip . We estimate an uncertainty for Jz,eff of ± 0.1 cm−1.

The parameters obtained for the two Fe sites are essentially the same, thus, D stands for D1 = D2 etc.

The two sites have different values for Az, indicated by the double entries.

The local electric field gradient tensors (EFG) are rotated relatrive to the ZFS by αEFG = 0°, βEFG = 20(5)° and γEFG = 40(10)°; the Euler angles (αEFG, βEFG, γEFG) rotate the principal axis frame of the EFG, (X, Y, Z), into the (x,y,z).

4. DISCUSSION

It is shown here that ADO can carry out reactions other than deformylation of long chain fatty aldehydes. This observation was facilitated by using liquid rather than head space GC/MS, which afforded the detection of low volatility compounds, and by investigating aldehydes shorter than the C18 physiological substrate. Importantly, it is shown that all reactions of ADO require O2 and that oxygen from [18O]-O2 is incorporated into the (n-1) alcohol products reported here. This suggests that the diiron cluster can activate oxygen and promote reaction chemistry similar to that observed for MMO and other diiron cluster-containing oxygenases. This is consistent with the formation of a high valent intermediate at some point in the ADO reaction cycle. The relevance of such a species to the deformylation and oxygenation reactions is discussed here.

4.1 Correlation of Substrate Chain-Length and Alternative Product Formation

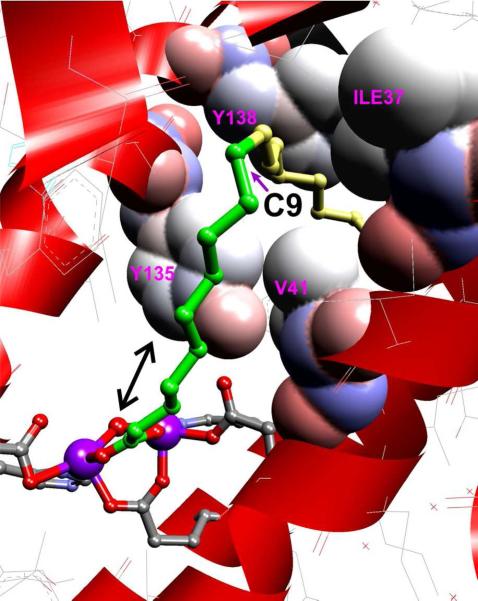

It is shown above that the relative yields of (n-1) alkane, alcohol and aldehyde products vary with the length of the substrate fatty aldehyde. The peak production of the (n-1) aldehyde and alcohol products relative to alkane occurs with C9-C10 length aldehyde substrates. The C9-C10 substrate length corresponds to the position of a ~ 90° bend in the substrate binding pocket of ADO relative to the diiron-cluster as revealed by the X-ray crystal structure of the diferric enzyme (PDB 2OC5)11 (Figure 9). Without the additional anchoring gained from binding on both sides of the bend, the (n-1) carbon of the shorter substrates may be able to shift more easily into position to react at the diiron cluster following release of the terminal carbon as formate as further discussed below. Such a shift would facilitate the types of reactions commonly observed for MMO and similar bacterial multicomponent dinuclear iron cluster-containing monooxygenases (BMM family). This suggests a mechanism that accounts for both deformylation and the formation of (n-1) alcohol and aldehyde products.

Figure 9.

The crystal structure of ADO (PDB 2OC5)11 showing a C18 fatty acid bound to the cluster. The binding orientation of the fatty acid is presumably that of the aldehyde substrate and reveals a sharp bend after carbon 9 (the first 9 carbons prior to the bend are shown in green). The bend is enforced by the labeled residues which are shown with van der Waals radii superimposed.

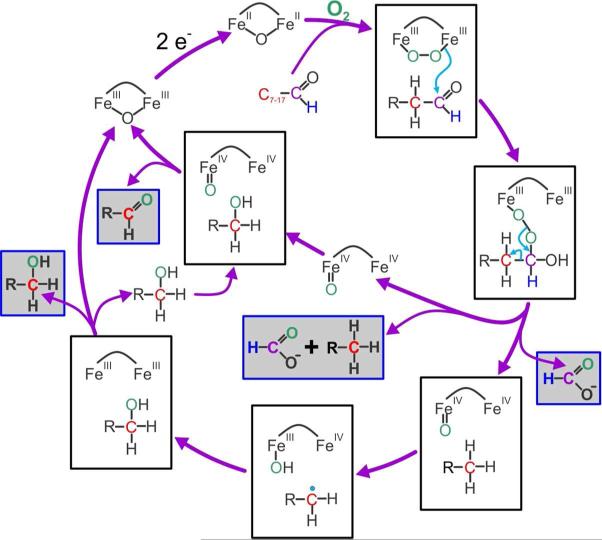

4.2 A Proposal for the Mechanism of ADO and the Formation of (n-1) Products

Members of the BMM family normally react poorly with aldehyde substrates, and these reactions result in oxidation rather than deformylation. In contrast, some cytochrome P450s such as sterol 14R demethylase (CYP51) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis react with aldehyde adducts of steroids resulting in deformylation and desaturation of the steroid.56-58 Computational studies have suggested that the CYP51 reaction is initiated by attack of the heme FeIII-peroxo-intermediate at the aldehydic carbon to form an Fe-peroxo-hemiacetal intermediate. In the protein environment, this initiates facile heterolytic C-C bond cleavage58 to yield a substrate carbanion and an Fe peroxoformate adduct. Heterolytic O-O bond cleavage would yield formate and the FeIV-oxo heme pi cation radical compound I of CYP51, but this reaction is apparently coupled with one electron transfer from the substrate carbanion to yield Compound II. Compound II can, in turn, accept a second electron from the substrate to yield the desaturated product.

Very similar chemical steps can be proposed for the initial deformylation reaction carried out by ADO (Figure 10). A peroxo intermediate isoelectic to that formed in P450 is observed for most members of the BMM family.29,32,34,59,60 One electron from each iron of the diferrous cluster is transferred to O2 as the adduct forms. Attack of this species on the substrate aldehyde and subsequent C-C bond cleavage could proceed as described for CYP51. However, the additional activation energy required to abstract an electron from the carbanion located on the primary carbon of the alkane versus the secondary carbon of the steroidal ring suggests that electron transfer coincident with O-O bond cleavage is unlikely. The product of direct expulsion of formate would be an FeIVFeIV-oxo species isoelectronic with Compound I of P450. Such a species has been trapped and characterized as compound Q of the MMOH catalytic cycle.32,34,61

Figure 10.

Proposed mechanism for ADO reaction. Observed products are boxed with gray background.

MMOH compound Q is known to carry out many types of reactions including desaturation.32 However, desaturation has not been described for the terminal C-C bond of saturated straight chain hydrocarbon substrates. In contrast, two well characterized reactions of compound Q are hydrocarbon hydroxylation at the primary carbon and oxidation of alcohols to aldehydes.41 If ADO forms a Q-like intermediate as a consequence of the deformylation reaction, then it might form the (n-1) alcohol and aldehyde products we observe here by the mechanism shown in Figure 10. The initially formed (n-1) hydrocarbon could either be released or remain in the active site and shift to react with the putative Q-like intermediate via a hydrogen atom abstraction and rebound mechanism similar to that described for MMO. Release of the resulting alcohol, followed by rebinding to the fraction of ADO that initially released hydrocarbon, could result in (n-1) aldehyde formation because this fraction would retain a Q-like intermediate.

Several predictions can be made based on the mechanism shown in Figure 10. First, the (n-1) alcohol product should be 13C-labeled at (the new) C1 when the substrate aldehyde is doubly-labeled at C1 and C2, because it is formed without intermediate release from the enzyme. Second, the release and rebinding of the intermediate alcohol suggests that addition of 13C-labeled alcohol to a reaction started with unlabeled substrate aldehyde would result in incorporation of label into the (n-1) aldehyde. Third, the total product, and in particular, the ratio of the (n-1) alkane and aldehyde products would not be altered by addition of exogenous alcohol, because the maximum aldehyde yield is determined by the fraction of enzyme that initially releases (n-1) alkane. Fourth, the ratio of alkane released versus bound is likely to depend strongly on the nature of the initial aldehyde substrate. Consequently, the distribution of (n-1) products should differ from substrate to substrate. Each of these predictions has been shown here to be correct.

One potential difficulty with the mechanism is the possible binding of substrate aldehyde to the fraction of ADO with an active Q-like cluster following release of the alkane. This might compete with the low concentration of diffusible alcohol product to form an (n-1) carboxylic acid product, but no enzyme-dependent acid formation is observed.

The mechanism we propose suggests that ADO can utilize the diiron-cluster to carry out three substantially different types of chemistry, namely attack by a peroxo adduct leading to deformylation, hydrogen atom abstraction followed by rebound to give alkane hydroxylation, and two electron oxidation of an alcohol. The latter two reactions are well known reactions for MMO, but the first reaction has not been observed. This suggests that the reactive diiron cluster of ADO, while similar to that of MMOH, must have specific differences that tune it to aldehyde deformylation. We do not yet know what these difference are, but we wish to make two comments. The integer spin EPR signals of diferrous ADO and MMOH are quite similar. This similarity reflects two properties of the electronic states: First, in both proteins the two FeII have negative zero-field splittings which yield local ground states derived from the m1 = ±2 and m2=±2 spin levels of the two local sites. Second, both proteins have diiron(II) centers coupled by weak ferromagnetic exchange interactions. While the two clusters look deceptively similar from the perspective of EPR, the Mössbauer data reveal substantial differences. Thus, diferrous ADO has (essentially) equivalent FeII sites in structurally well-defined environments, in contrast to diferrous MMOH which has inequivalent Fe sites as witnessed by the observations that the sites have very distinct ΔEQ values (ΔEQ(1) ≈ 3.2 mm/s and ΔEQ(1) ≈ 2.4 mm/s44) and different magnetic hyperfine tensors (see Figure 13 of Fox et al. 199342). ΔEQ(1) of MMOH is well defined (in all preparations), yielding a quadrupole doublet with sharp lines. In contrast, ΔEQ(2) in all preparations is distributed with a variance σΔEQ = 0.3 mm/s if a Gaussian distribution about the average 2.4 mm/s is assumed. This distribution reflects a structural heterogeneity which is not yet understood. However, the successful analysis of the ADO spectra gives us confidence that we may obtain, finally, a good set of spin Hamiltonian parameters of this important protein.

The small value obtained for the exchange coupling constant of diferrous ADO (J ≈ −0.2 cm−1) suggests, based on the reported studies of MMOH and RNR-R2,31,32,42 that the ferrous sites are bridged by two carboxylates with, however, unknown bridging modes ( μ-(η1, η2 and/or μ-1,3 coordination, see Wei et al. 2004).62 The bearing of these differences on the distinct reactivities of the two enzymes is not clear and will require further study.

4.3 Comparison with Previous Mechanistic Studies

Previous studies of ADO from two different cyanobacteria have shown that (i) oxygen from [18O]-O2 is incorporated into the product formate, (ii) hydrogen is retained by the terminal carbon, and that (iii) hydrogen from solvent is incorporated into the alkane product.14,26 Each of these findings is consistent with the mechanism proposed in Figure 10. Recently, it has been shown that an alternative octadecanal substrate with an additional cyclopropyl group at C3-C4 is converted to a ring open terminal alkene product characteristic of intermediate radical formation.63 It was suggested that one way this could occur is through homolytic C-C bond cleavage. The alternative presented in Figure 10 is that the substrate radical is formed as in the MMO reaction by hydrogen atom abstraction from the cyclopropyl alkane. Delocalization and ring opening would then rapidly occur, but in an MMO-type reaction rebound of the hydroxyl radical would be expected to yield octadecanol. Instead, enzyme inactivation and formation of a covalent adduct occurred, presumably by trapping of the radical by a group in the enzyme active site. The mechanisms that have been proposed by others for ADO based on previous studies require the input of 4 electrons from NADH or another source for each cycle, because the FeIIIFeIII cluster must be reduced to the FeIIFeII state to bind O2 and then the equivalent of the FeIVFeIV cluster remaining after the deformylation reaction must be returned to the FeIIIFeIII state. The mechanism proposed here requires only 2 electrons from NADH because the formal FeIVFeIV species is utilized for mixture of hydroxylation and oxidation reactions in which the electrons are derived from the substrates. Unfortunately, it is not currently possible to accurately account for NADH (or other reducing equivalent) utilization because the authentic biological reductase has not been isolated.

CONCLUSIONS

We show here that ADO is a significantly more versatile catalyst than previously recognized. It is apparently possible to activate the enzyme for alkane hydroxylation by reacting the enzyme with an intermediate chain aldehyde. The C-H bond dissociation energy of the substrate alkane for the hydroxylation reaction is approximately 98 kcal per mole, placing ADO among the most potent biological oxidants. This strongly supports the formation of a compound Q-like intermediate as a key feature of the ADO mechanism and opens the possibility of adapting the enzyme for a wide range of chemistry involving abundant hydrocarbons.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by NIH Grant GM100943 to J.D.L., NSF Grant EB-001475 to E.M. University of Minnesota Initiative for Renewable Energy and the Environment Grant to J.D.L. Funding for NMR instrumentation was provided by the Office of the Vice President for Research, the Medical School, the College of Biological Science, NIH, NSF, and the Minnesota Medical Foundation. The authors are thankful for the contributions of the following people: Fred Schendel (fermentation, Univ. of Minn. Biotech Resource Center), Tom Krick (HPLC-MS, U. of Minn. Center for Mass Spectroscopy and Proteomics), Todd Rappe (13C-NMR, U. of Minn. Biomedical NMR Resource Center) and to Jennifer Seffernick and Anna Komor for helpful discussion.

Footnotes

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information Available. Methods for HPLC-MS detection of formate and formaldehyde, CO detection, syntheses of 13C-labeled compounds, EPR and Mössbauer; Time course of heptane production; GC/FID chromatograms of ADO reaction with ferredoxin/ferredoxin reductase; 13C-NMR analysis of synthesized [1-13C]-nonanal and [1,2-13C]-octanal; MS of 13C-heptane product of ADO reaction with [1,2-13C]-octanal, HPLC-MS analysis of derivatized [13C]-formaldehyde; investigation of co-production in ADO reaction, O2 depleted ADO reaction; comments on EPR and Mössbauer data analysis including Mössbauer spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lam MK, Lee KT. Biotech. Adv. 2012;30:673. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones CS, Mayfield SP. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012;23:346. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malcata FX. Trends Biotechnol. 2011;29:542. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kung Y, Runguphan W, Keasling J. ACS Synth. Biol. 2012;1:498. doi: 10.1021/sb300074k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berry DA, Robertson DE, Skraly FA, Green BD, Ridley CP, Kosuri S, Reppas NB, Sholl M, Afeyan NB. Joule Biotechnologies, Inc.; USA: 2009. WO2009111513A1. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schirmer A, Rude M, Brubaker S. LS9, Inc.; USA: 2010. US20100249470A1. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berry DA, Robertson DE, Skraly FA, Green BD, Ridley CP, Kosuri S, Reppas NB, Sholl M, Afeyan NB. Joule Unlimited, Inc.; USA: 2011. US20110262975A1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franklin S, Somanchi A, Wee J, Rudenko G, Moseley J, Rakitsky W, Zhao X, Bhat R. Solazyme, Inc.; USA: 2012. WO2012106560A1. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee GJ, Haliburton JR, Hu Z, Schirmer AW. LS9, Inc.; USA: 2013. WO2013039563A1. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shanklin J, Andre C. Brookhaven Science Associates, LLC; USA: 2013. WO2013032891A1. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schirmer A, Rude MA, Li X, Popova E, del Cardayre SB. Science. 2010;329:559. doi: 10.1126/science.1187936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dennis M, Kolattukudy PE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:5306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warui DM, Li N, Nørgaard H, Krebs C, Bollinger JM, Booker SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:3316. doi: 10.1021/ja111607x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li N, Nørgaard H, Warui DM, Booker SJ, Krebs C, Bollinger JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:6158. doi: 10.1021/ja2013517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li N, Chang WC, Warui DM, Booker SJ, Krebs C, Bollinger JM. Biochemistry. 2012;51:7908. doi: 10.1021/bi300912n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shanklin J, Guy JE, Mishra G, Lindqvist Y. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:18559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R900009200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedle S, Reisner E, Lippard SJ. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:2768. doi: 10.1039/c003079c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nordlund P, Eklund H. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;232:123. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenzweig AC, Frederick CA, Lippard SJ, Nordlund P. Nature. 1993;366:537. doi: 10.1038/366537a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elango N, Radhakrishnan R, Froland W, Wallar B, Earhart C, Lipscomb J, Ohlendorf D. Protein Sci. 1997;6:556. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathevon C, Pierrel F, Oddou J, Garcia-Serres R, Blonclin G, Latour J, Menage S, Gambarelli S, Fontecave M, Atta M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:13295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704338104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindqvist Y, Huang W, Schneider G, Shanklin J. EMBO J. 1996;15:4081. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman LM, Wackett LP. Biochemistry. 1995;34:14066. doi: 10.1021/bi00043a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sazinsky MH, Bard J, Di Donato A, Lippard SJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:30600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400710200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pikus JD, Studts JM, Achim C, Kauffmann KE, Münck E, Steffan RJ, McClay K, Fox BG. Biochemistry. 1996;35:9106. doi: 10.1021/bi960456m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eser BE, Das D, Han J, Jones PR, Marsh EN. Biochemistry. 2011;50:10743. doi: 10.1021/bi2012417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eser BE, Das D, Han J, Jones PR, Marsh EN. Biochemistry. 2012;51:5703. doi: 10.1021/bi300837j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bollinger JM, Jr., Diao Y, Matthews ML, Xing G, Krebs C. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 2009:905. doi: 10.1039/b811885j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song WJ, Behan RK, Naik SG, Huynh BH, Lippard SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:6074. doi: 10.1021/ja9011782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tinberg CE, Song WJ, Izzo V, Lippard SJ. Biochemistry. 2011;50:1788. doi: 10.1021/bi200028z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burdi D, Willems J-P, Riggs-Gelasco P, Antholine WE, Stubbe J, Hoffman BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:12910. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallar BJ, Lipscomb JD. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2625. doi: 10.1021/cr9500489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kovaleva EG, Neibergall MB, Chakrabarty S, Lipscomb JD. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:475. doi: 10.1021/ar700052v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tinberg CE, Lippard SJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011;44:280. doi: 10.1021/ar1001473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kende AS, Fludzinski P. Org. Synth. Coll. Vol. 1990;7:221. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liedtke RJ, Djerassi C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969;91:6814. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Das D, Eser BE, Han J, Sciore A, Marsh EN. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011;50:7148. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andre C, Kim SW, Yu X-H, Shanklin J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:3191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218769110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nash T. Biochem. J. 1953;55:416. doi: 10.1042/bj0550416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller MA, Lipscomb JD. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:5524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stirling DI, Colby J, Dalton H. Biochem. J. 1979;177:361. doi: 10.1042/bj1770361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fox BG, Hendrich MP, Surerus KK, Andersson KK, Froland WA, Lipscomb JD, Münck E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:3688. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hendrich MP, Münck E, Fox BG, Lipscomb JD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:5861. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Banerjee R, Meier KK, Münck E, Lipscomb JD. Biochemistry. 2013;52:4331. doi: 10.1021/bi400182y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu KE, Valentine AM, Wang D, Huynh BH, Edmondson DE, Salifoglou A, Lippard SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:10174. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shanklin J, Achim C, Schmidt H, Fox BG, Münck E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:2981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shu L, Nesheim JC, Kauffmann K, Münck E, Lipscomb JD, Que L. Science. 1997;275:515. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5299.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shu L, Broadwater J, Achim C, Fox B, Münck E, Que L. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1998;3:392. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cadieux E, Vrajmasu V, Achim C, Powlowski J, Münck E. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10680. doi: 10.1021/bi025901u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murray LJ, García-Serres R, Naik S, Huynh BH, Lippard SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:7458. doi: 10.1021/ja062762l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Makris TM, Chakrabarti M, Münck E, Lipscomb JD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:15391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007953107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fox BG, Surerus KK, Münck E, Lipscomb JD. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:10553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Juarez-Garcia CH. Carnegie Mellon University. 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lynch JB, Juarez-Garcia C, Münck E, Que L., Jr. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:8091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Münck E, Surerus KK, Hendrich MP. Methods Enzymol. 1993;227:463. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)27019-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akhtar M, Calder MR, Corina DL, Wright JN. Biochem. J. 1982;201:569. doi: 10.1042/bj2010569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vaz AD, Pernecky SJ, Raner GM, Coon MJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:4644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sen K, Hackett JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10293. doi: 10.1021/ja906192b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bailey LJ, Fox BG. Biochemistry. 2009;48:8932. doi: 10.1021/bi901150a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Korboukh VK, Li N, Barr EW, Bollinger JM, Jr., Krebs C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:13608. doi: 10.1021/ja9064969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee SK, Fox BG, Froland WA, Lipscomb JD, Münck E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:6450. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wei P.-p., Skulan AJ, Mitić N, Yang Y-S, Saleh L, Bollinger JM, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:3777. doi: 10.1021/ja0374731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paul B, Das D, Ellington B, Marsh EN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:5234. doi: 10.1021/ja3115949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.