Abstract

Background:

Diabetes-related end-stage renal disease disproportionately affects indigenous peoples. We explored the role of differential mortality in this disparity.

Methods:

In this retrospective cohort study, we examined the competing risks of end-stage renal disease and death without end-stage renal disease among Saskatchewan adults with diabetes mellitus, both First Nations and non–First Nations, from 1980 to 2005. Using administrative databases of the Saskatchewan Ministry of Health, we developed Fine and Gray subdistribution hazards models and cumulative incidence functions.

Results:

Of the 90 429 incident cases of diabetes, 8254 (8.9%) occurred among First Nations adults and 82 175 (90.9%) among non–First Nations adults. Mean age at the time that diabetes was diagnosed was 47.2 and 61.6 years, respectively (p < 0.001). After adjustment for sex and age at the time of diabetes diagnosis, the risk of end-stage renal disease was 2.66 times higher for First Nations than non–First Nations adults (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.24–3.16). Multivariable analysis with adjustment for sex showed a higher risk of death among First Nations adults, which declined with increasing age at the time of diabetes diagnosis. Cumulative incidence function curves stratified by age at the time of diabetes diagnosis showed greatest risk for end-stage renal disease among those with onset of diabetes at younger ages and greatest risk of death among those with onset of diabetes at older ages.

Interpretation:

Because they are typically younger when diabetes is diagnosed, First Nations adults with this condition are more likely than their non–First Nations counterparts to survive long enough for end-stage renal disease to develop. Differential mortality contributes substantially to ethnicity-based disparities in diabetes-related end-stage renal disease and possibly to chronic diabetes complications. Understanding the mechanisms underlying these disparities is vital in developing more effective prevention and management initiatives.

Indigenous peoples experience an excess burden of diabetes-related end-stage renal disease,1–4 but the reasons for this disparity are incompletely understood. Although the increase in end-stage renal disease among indigenous peoples has paralleled the global emergence of type 2 diabetes mellitus,5 disparities in end-stage renal disease among Canada’s First Nations adults persist2 after adjustment for elevated prevalence of diabetes.6 In an earlier study, we suggested that First Nations adults might be more prone to diabetic nephropathy and might experience more rapid progression to end-stage renal disease.7 However, although albuminuria is more prevalent in this population,8 affected individuals unexpectedly have a longer average time from diagnosis of diabetes to end-stage renal disease than people from non–First Nations populations.2 These findings could be explained by a younger age at the time of diabetes diagnosis6 and lower mortality among those with chronic kidney disease.8 An age-related survival benefit among First Nations adults with diabetes could lead to longer exposure to the metabolic consequences of diabetes and greater likelihood of end-stage renal disease.

Our objective was to examine the contribution of differential mortality to disparities in diabetes-related end-stage renal disease within large populations of indigenous and non-indigenous North Americans. Accordingly, we used competing-risks survival analysis to compare the simultaneous risks of diabetes-related end-stage renal disease and death without end-stage renal disease among First Nations and non–First Nations adults.9

Methods

Study populations

In this retrospective, population-based cohort study, we examined the competing risks of end-stage renal disease and death without end-stage renal disease among Saskatchewan adults in whom diabetes was diagnosed from 1980 to 2005, using data from the province’s physicians’ services, hospital separation and person registry databases. The study was approved by the University of Saskatchewan Research Ethics Board, and its populations have been previously described.2,6 Briefly, the Canadian province of Saskatchewan has a population of about 1 million. About 99% of its citizens are beneficiaries of a universal health care system that generates administrative data for the Ministry of Health. Beneficiaries were subdivided into self-identified First Nations registered under section 6 of the Indian Act of Canada and non–First Nations. The latter are predominantly white, but this group also includes nonregistered First Nations (< 0.5%) and Métis (of mixed First Nations and non–First Nations heritage; about 5%).6

We identified cases of diabetes using a validated algorithm.6,10 For each participant, the diabetes incident year was the first calendar year in which the case definition was met. We excluded persons whose diabetes occurred before age 20 years and women with gestational diabetes.6 We identified end-stage renal disease using an algorithm based on physicians’ fee-for-service codes for long-term dialysis and renal transplantation.2 The incident year for end-stage renal disease was the calendar year in which the person started dialysis or underwent a preemptive transplant.2

Although we could not identify the underlying cause, cases of end-stage renal disease that occurred in the same year as the case definition for diabetes was met (or thereafter) were designated as diabetes-related end-stage renal disease. Time from diagnosis of diabetes to diagnosis of end-stage renal disease was designated as 0.5 years when the 2 diagnoses occurred in the same calendar year. We excluded people whose end-stage renal disease occurred before diabetes. Finally, we obtained sex, birth year, death year and loss of health care coverage for all study participants.

Statistical analysis

We compared the distributions of individual-level variables between ethnic groups using t tests and χ2 tests. The significance level for all descriptive, univariable and multivariable analyses (including interactions) was 0.05.

We used competing-risks survival analysis to compare the simultaneous risks of end-stage renal disease or death without end-stage renal disease in the 2 populations.9 Survival time was the number of years from the age of diabetes diagnosis until either diagnosis of end-stage renal disease or death without end-stage renal disease. We previously compared different statistical modelling approaches to optimize the analysis of competing-risks data.11 Accordingly, for the current study, we used the Fine and Gray model,12,13 a semiproportional subhazards model that provides the cumulative incidence (or sub-distribution) of each event of interest (diagnosis of end-stage renal disease or death before end-stage renal disease) while simultaneously considering the competing risk of the other outcome. Thus, people who die before end-stage renal disease occurs are not censored in a way that might bias the estimates, as is possible in a Cox cause-specific analysis. First, we used univariable analysis to test whether there was a significant effect of ethnicity, sex or age at diabetes diagnosis. For the multivariable analysis, we included predictors shown to be significant in the univariable analysis, as well as significant interactions.

We created cumulative incidence function curves to illustrate the probability of end-stage renal disease or death without end-stage renal disease by sex and ethnicity over the study period. We plotted the overall cumulative incidence of the 2 events against years since diabetes diagnosis and compared sex-specific results using Gray’s test.14 We also stratified curves by age at diabetes diagnosis (20 to < 40 yr, 40–60 yr, > 60 yr).

We performed statistical analyses with SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R-package cmprsk (www.R-project.org).

Results

Study population

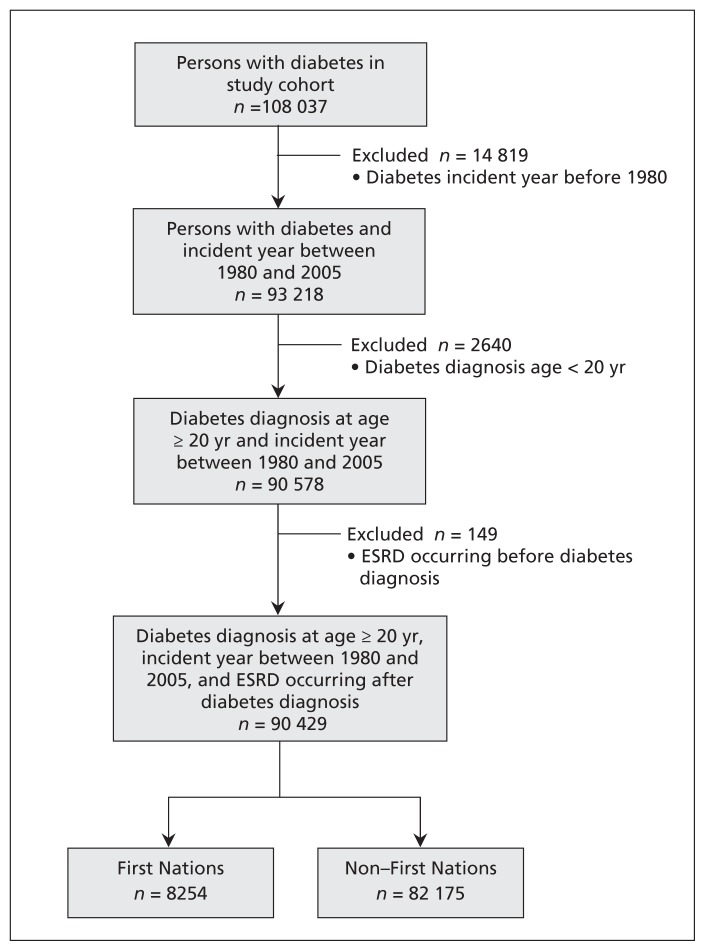

From 1980 to 2005, a total of 90 429 cases of diabetes meeting our study criteria were identified in Saskatchewan (Figure 1). The mean age at diabetes diagnosis among the 8254 First Nations individuals was 47.2 years, and 3718 (45.0%) were male (Table 1). Among the 82 175 non–First Nations individuals, the mean age at diagnosis was 61.6 years, and 44 820 (54.5%) were male. For First Nations individuals, diabetes was most often diagnosed up to age 60 (6777 or 82.1%), whereas among non–First Nations individuals, diabetes was most often diagnosed after age 60 (46 025 or 56.0%). End-stage renal disease occurred in 200 (2.4%) of the First Nations participants, and 1482 (18.0%) of this group died without end-stage renal disease. End-stage renal disease occurred in 600 (0.7%) of the non–First Nations individuals, and 28 450 (34.6%) of this group died without end-stage renal disease. Overall, 53 627 (59.3%) of the cases were censored (> 90% of these because the end of the study period was reached and about 7% because of loss of health care coverage).

Figure 1:

Identification of study participants. ESRD = end-stage renal disease.

Table 1:

Key characteristics of study groups

| Variable | Group; no. (%) of participants*† | |

|---|---|---|

| First Nations (n = 8 254) | Non–First Nations (n = 82 175) | |

| Sex, male | 3 718 (45.0) | 44 820 (54.5) |

| Age at diabetes diagnosis | ||

| Mean ± SD | 47.2 ± 14 | 61.6 ± 15.3 |

| < 40 yr | 2 685 (32.5) | 7 290 (8.9) |

| 40–60 yr | 4 092 (49.6) | 28 860 (35.1) |

| > 60 yr | 1 477 (17.9) | 46 025 (56.0) |

| End-stage renal disease | ||

| No. (%) of participants | 200 (2.4) | 600 (0.7) |

| Age at diagnosis, yr, mean ± SD | 56.5 ± 11.2 | 64.1 ± 13.7 |

| Death without end-stage renal disease | ||

| No. (%) of participants | 1 482 (18.0) | 28 450 (34.6) |

| Age at death, yr, mean ± SD | 66.4 ± 14.4 | 78.3 ± 11.1 |

SD = standard deviation.

Unless otherwise indicated.

All differences between groups were statistically significant (p < 0.001) by t test (continuous variables) or χ2 test (categorical variables).

Competing-risks analysis

Univariable models showed that male sex increased the risk for both events of interest (end-stage renal disease and death without end-stage renal disease) (Table 2). The risk of end-stage renal disease was 3.86 (95% confidence interval [CI] 3.29–4.53) times higher among First Nations participants than among non–First Nations participants, but the risk of death without end-stage renal disease was only 0.49 (95% CI 0.47–0.52) as high among First Nations participants. Increasing age at the time of diabetes diagnosis reduced the risk of end-stage renal disease but increased the risk of death without this condition.

Table 2:

Univariable Fine and Gray modelling of relations between significant variables and competing risk events

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95% CI)* |

|---|---|

| End-stage renal disease | |

| Sex, male | 1.42 (1.23–1.64) |

| First Nations ethnicity | 3.86 (3.29–4.53) |

| Age at diabetes diagnosis, per yr | 0.964 (0.960–0.967) |

| Death without end-stage renal disease | |

| Sex, male | 1.21 (1.19–1.23) |

| First Nations ethnicity | 0.49 (0.47–0.52) |

| Age at diabetes diagnosis, per yr | 1.08 (1.08–1.08) |

Note: CI = confidence interval.

All differences statistically significant (p < 0.001) based on p values and 95% CIs generated by Fine and Gray modelling.

The final multivariable model showed that the risk of end-stage renal disease was 2.66 times higher among First Nations participants than among non–First Nations participants (Table 3). Men experienced a 49% higher risk of end-stage renal disease than women. Increasing age at the time of diabetes diagnosis reduced the risk of end-stage renal disease by about 3% per year after adjustment for ethnicity and sex. There were no significant interactions.

Table 3:

Multivariable Fine and Gray modelling of relations between significant variables and competing risk events

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95% CI)* |

|---|---|

| End-stage renal disease | |

| Sex, male | 1.49 (1.29–1.72) |

| First Nations ethnicity | 2.66 (2.24–3.16) |

| Age at diabetes diagnosis, per yr | 0.969 (0.966–0.973) |

| Death without end-stage renal disease | |

| Sex, male | 2.25 (1.96–2.58) |

| First Nations ethnicity | 3.13 (2.49–3.92) |

| Age at diabetes diagnosis, per yr | 1.08 (1.08–1.08) |

| Interaction: age at diabetes diagnosis × First Nations ethnicity | 0.986 (0.982–0.990) |

| Interaction: age at diabetes diagnosis × male sex | 0.994 (0.992–0.996) |

Note: CI = confidence interval.

All differences statistically significant (p < 0.001) based on p values and 95% CIs generated by Fine and Gray modelling.

The final multivariable model for death without end-stage renal disease showed interactions between sex, ethnicity and age at the time of diabetes diagnosis. Like the univariable model, the multivariable model showed that increasing age at the time of diabetes diagnosis and male sex increased the risk of death without end-stage renal disease. Unlike the univariable model, however, the multivariable model showed that First Nations participants experienced a higher risk of death without end-stage renal disease than non–First Nations participants in a significant interaction with age at time of diabetes diagnosis (after adjustment for sex). Thus, the degree of elevation in the hazard ratio for death without end-stage renal disease among First Nations compared with non–First Nations individuals slowly diminished with increasing age at the time of diabetes diagnosis.

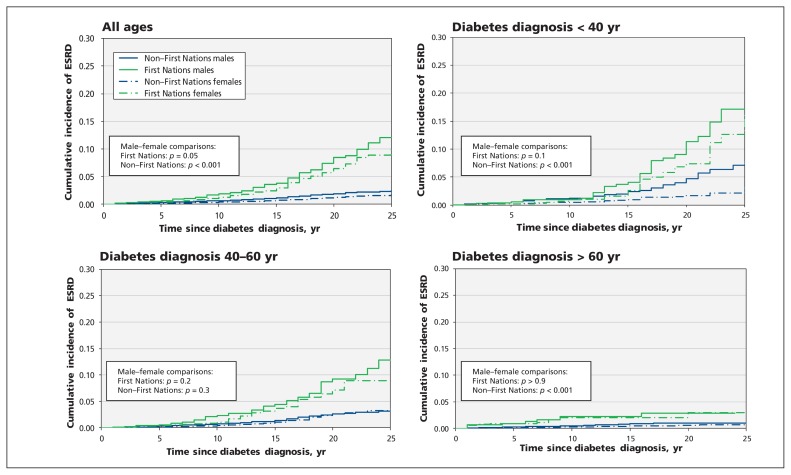

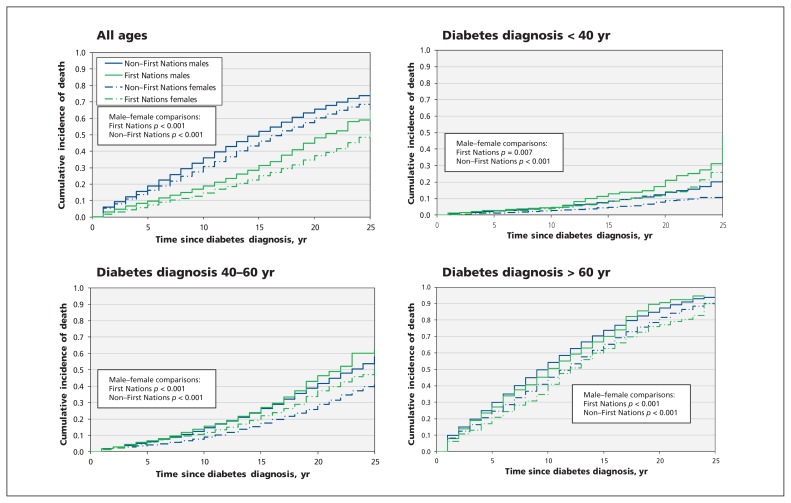

Cumulative incidence function curves

Cumulative incidence function curves for end-stage renal disease (Figure 2) and death without end-stage renal disease (Figure 3), both overall and stratified by age at the time of diabetes diagnosis, were generated by ethnicity and sex. Overall, there were significant differences among the 4 complete groups (First Nations men, First Nations women, non–First Nations men, non–First Nations women) in the probability of both end-stage renal disease and death without end-stage renal disease (p < 0.001). First Nations individuals experienced a higher probability of end-stage renal disease and a lower probability of death without end-stage renal disease over time than non–First Nations individuals. For each overall outcome, men from both ethnic groups experienced a significantly greater risk than women with increasing duration of diabetes. The ethnicity-based disparity in risk of end-stage renal disease was present regardless of age at the time of diabetes diagnosis. However, the curves for risk of end-stage renal disease over time flattened progressively in both groups with increasing age at time of diabetes diagnosis. Thus, among both First Nations and non–First Nations participants who were older than 60 at the time diabetes was diagnosed, end-stage renal disease occurred in less than 5%, even after 25 years of diabetes.

Figure 2:

Cumulative incidence function curves for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in study populations, for all ages and stratified by age at time of diabetes diagnosis. For most First Nations participants, diabetes was diagnosed when they were 60 years of age or younger, when the incidence of ESRD is higher. Conversely, for most non–First Nations participants, diabetes was diagnosed when they were older than 60 years of age, when the incidence of ESRD is lowest. Particularly among First Nations people, men consistently experienced a trend toward higher incidence of end-stage renal disease than women, regardless of age group at time of diagnosis, although the differences for comparisons with small sample sizes were not significant.

Figure 3:

Cumulative incidence function curves for mortality in study populations, for all ages and stratified by age at time of diabetes diagnosis. For most First Nations participants, diabetes was diagnosed when they were 60 years of age or younger, when mortality rates are lower. Conversely, for most non–First Nations participants, diabetes was diagnosed when they were older than 60 years of age, when mortality rates are highest.

Despite the overall higher risk of death without end-stage renal disease among non–First Nations individuals over time, ethnicity-based disparities were less clear when stratified by age at the time of diabetes diagnosis. Apart from those in whom diabetes was diagnosed the earliest, the most consistent differences were observed between sexes: compared with women, men with diabetes diagnosed in all age strata (both First Nations and non–First Nations) had a greater risk of death without end-stage renal disease with increasing duration of diabetes. In contrast to end-stage renal disease, the cumulative incidence of death without end-stage renal disease over time was progressively higher with each increase in age stratum for time of diabetes diagnosis.

Interpretation

Differential mortality amplifies the risk of end-stage renal disease among First Nations adults with diabetes. Because they are younger than non–First Nations individuals when diabetes first develops, First Nations individuals are more likely to survive long enough for end-stage renal disease to occur, presumably because of lower cardiovascular mortality.15 This phenomenon occurs in the formerly perplexing context of higher age-adjusted mortality among First Nations individuals with diabetes.8,16,17 It also explains our earlier observation that the time from diabetes diagnosis to end-stage renal disease is significantly longer among First Nations individuals,2 despite evidence for poorer quality of diabetes care18,19 and a larger proportion of patients with early diabetic nephropathy.8,20 These findings are notable because they reveal an important mechanism underlying ethnicity-based disparities in end-stage renal disease that has serious long-term implications for First Nations and other indigenous populations. They may also help to explain similar disparities in other diabetic complications.20,21

Although differences in diabetes-related incidence of end-stage renal disease have diminished between First Nations and non–First Nations populations in Canada2 and between comparable populations in the United States,22 significant ethnicity-based disparities in end-stage renal disease persist2,22 and have remained incompletely understood. Known contributing factors include genetic3 and other prenatal determinants,23 environmental factors such as glycemic and blood pressure control8,24 and social determinants such as quality of and access to health care.18,19 We have now confirmed that an age-related survival advantage after diabetes diagnosis also contributes to the elevated risk for diabetes-related end-stage renal disease among First Nations individuals.

End-stage renal disease and death without end-stage renal disease are competing risks among people with diabetes, because each precludes the other.9 Because end-stage renal disease reduces quality of life and its treatment is resource intensive, death after a normal life span without end-stage renal disease is the preferred outcome. Nonetheless, few studies have considered this issue among people with diabetes. Agarwal and associates25 and Derose and colleagues26 examined the predictors of end-stage renal disease versus death among people with all-cause chronic kidney disease, as did the FinnDiane Study Group among people with type 1 diabetes.13 We are not aware of any other population-based studies that have examined the contribution of competing risks to ethnicity-based disparities in diabetes-related end-stage renal disease between indigenous and non-indigenous peoples. However, our findings are consistent with the results of a study comparing Pima Indians with onset of type 2 diabetes in youth or adulthood. In that study, a higher incidence of end-stage renal disease in the younger cohort by middle age was largely attributable to longer duration of diabetes.27

The implications of our findings are sobering. Among First Nations adults, type 2 diabetes is increasingly occurring during younger decades of life.6 Among First Nations children, the prevalence of diabetes tripled between 1980 and 2005,28 and the offspring of these individuals are in turn experiencing an even higher risk of childhood type 2 diabetes.29 These demographic trends suggest that steadily increasing numbers of young First Nations individuals will face prolonged exposure to the metabolic consequences of type 2 diabetes. Without substantial improvements in the prevention and treatment of this disease, this pattern will likely translate into increasing numbers of First Nations people with diabetes-related end-stage renal disease and possibly other chronic diabetic complications.

What can we learn from these observations? First, they reinforce the need for an emphasis on diabetes prevention and management initiatives for First Nations children and young adults, with particular attention to diabetes in pregnancy.6 Second, strategies to postpone type 2 diabetes should be considered: if the occurrence of diabetes can be delayed, it seems plausible that the risk of chronic complications and premature deaths will be reduced. Finally, addressing disparities in both accessibility and quality of diabetes care8,19 is imperative to achieve therapeutic targets for glycemic, blood pressure and lipid control.18,19 Although the reasons underlying these disparities are complicated, they are also modifiable, and substantial improvements are likely during even the early stages of resolution.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this analysis include long duration of the study period, consideration of total populations, use of validated algorithms for both diabetes and end-stage renal disease, and our ability to distinguish First Nations and non–First Nations populations.2,6 We previously evaluated the most appropriate competing-risks methodology for analyzing this kind of data11 and, on the basis of that evaluation, used Fine and Gray models for the current analysis, as has been proposed by others.13

The limitations of the study include our inability to control for important predictors of end-stage renal disease and death without end-stage renal disease, such as glycemic, blood pressure and lipid control, and related changes in medical practice, such as the introduction of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors,30 that occurred during the course of the study period. However, these factors would not have affected the difference in age of diabetes onset between First Nations and non–First Nations people. We were unable to identify indigenous people other than First Nations, but this limitation would lead to underestimation of the real differences between First Nations and non–First Nations populations. We were also unable to distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes or among various causes of end-stage renal disease (diabetes versus other causes). Finally, the Fine and Gray model assumes proportional hazards12 between groups in the risks for end-stage renal disease and death without end-stage renal disease over time. We do not know if that assumption is entirely correct, but when we used Cox cause-specific models to analyze our data, the results (not shown) were very similar to those reported here.

Conclusion

In this competing-risks analysis, First Nations adults experienced a higher risk of both end-stage renal disease and death without end-stage renal disease. However, most non–First Nations individuals are older than 60 at the time of diabetes diagnosis, when cumulative risk of end-stage renal disease is lowest, and most First Nations adults are much younger when diabetes occurs, when the cumulative risk of end-stage renal disease is highest. Therefore, First Nations adults with diabetes are more likely to survive long enough to experience end-stage renal disease and possibly other chronic diabetic complications. More effective primary prevention initiatives are urgently needed to reduce the incidence of type 2 diabetes. Among those with diabetes, reduced rates of microalbuminuria and slowed progression of chronic kidney disease are achievable through early diagnosis, cessation of smoking and achievement of established clinical practice guideline targets for glycemic, blood pressure and lipid control. Finally, we suggest that delaying the onset of type 2 diabetes should now be considered in the overall strategy for reducing diabetes complications. Further research is required to evaluate the cost and effectiveness of screening for and treating pre-diabetes among indigenous peoples and others.

Acknowledgements

This study is based in part on non-identifiable data provided by the Saskatchewan Ministry of Health. The interpretations and conclusions of this article do not necessarily represent those of the Government of Saskatchewan or the Saskatchewan Ministry of Health.

See related commentary by McDonald on page 93 and at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.131605. See also research article by Samuel and colleagues on page E86 and at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.130776

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Ying Jiang helped design the study, performed the statistical analysis, interpreted the data and completed a master’s thesis based on this project. Nathaniel Osgood co-conceived and helped design the study, interpreted the data and supervised the analysis. Hyun-Ja Lim helped design the study, interpreted the data and supervised the statistical analysis. Mary Rose Stang helped design the study and acquired the data. Roland Dyck acquired the data, co-conceived and helped design the study, interpreted the data, oversaw the project and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion, reviewed and edited the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript submitted for publication.

Funding: During her MSc studies, Ying Jiang was supported by the Beijing Institute of Technology, the University of Saskatchewan and a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (awarded to Nathaniel Osgood). There was no other external funding for this study.

References

- 1.Burrows NR, Narva AS, Geiss LS, et al. End-stage renal disease due to diabetes among southwestern American Indians, 1990–2001. Diabetes Care 2005;28:1041–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyck RF, Osgood ND, Lin TH, et al. End-stage renal disease in people with diabetes: a comparison of First Nations people and other Saskatchewan residents from 1981–2005. Can J Diabetes 2010;34:324–33. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pavkov ME, Knowler WC, Hanson RL, et al. Diabetic nephropathy in American Indians, with a special emphasis on the Pima Indians. Curr Diab Rep 2008;8:486–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naqshbandi M, Harris SB, Esler JG, et al. Global complication rates of type 2 diabetes in indigenous peoples: a comprehensive review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2008;82:1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, et al. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1047–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dyck R, Osgood N, Lin TH, et al. Epidemiology of diabetes mellitus among First Nations and non–First Nations adults. CMAJ 2010;182:249–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyck RF, Tan L. Rates and outcomes of diabetic end-stage renal disease among registered native people in Saskatchewan. CMAJ 1994;150:203–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dyck RF, Sidhu N, Klomp H, et al. Differences in glycemic control and survival predict higher ESRD rates in diabetic First Nations adults. Clin Invest Med 2010;33:E390–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pintilie M. Competing risks: a practical perspective. Chichester (UK): John Wiley and Sons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hux JE, Ivis F, Flintoft V, et al. Diabetes in Ontario: determination of prevalence and incidence using a validated administrative data algorithm. Diabetes Care 2002;25:512–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim H, Zhang X, Dyck R, et al. Methods of competing risks analysis of end-stage renal disease and mortality among people with diabetes. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forsblom C, Harjutsalo V, Thorn LM, et al.; FinnDiane Study Group. Competing-risk analysis of ESRD and death among patients with type 1 diabetes and macroalbuminuria. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;22:537–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat 1988;16:1141–54. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris SB, Zinman B, Hanley A, et al. The impact of diabetes on cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes in a native Canadian population. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2002;55:165–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao S, Manns BJ, Culleton BF, et al.; Alberta Kidney Disease Network. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and survival among Aboriginal people. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;18:2953–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oster RT, Johnson JA, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. Recent epidemiologic trends of diabetes mellitus among status Aboriginal adults. CMAJ 2011;183:E803–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris SB, Naqshbandi M, Bhattacharyya O, et al.; CIRCLE Study Group. Major gaps in diabetes clinical care among Canada’s First Nations: results of the CIRCLE Study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2011;92:272–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deved V, Jette N, Quan H, et al.; Alberta Kidney Disease Network. Quality of care for First Nations and non-First Nations people with diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013;8:1188–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanley AJG, Harris SB, Mamakeesick M, et al. Complications of type 2 diabetes among Aboriginal Canadians. Diabetes Care 2005;28:2054–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young TK, Reading J, Elias B, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in Canada’s First Nations: status of an epidemic in progress. CMAJ 2000;163:561–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Narva AS. Reducing the burden of chronic kidney disease among American Indians. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2008;15:168–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson RG, Morgenstern H, Bennett PH. Intrauterine diabetes exposure and the risk of renal disease in diabetic Pima Indians. Diabetes 1998;47:1489–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dyck RF, Hayward M, Harris SB, et al.; CIRCLE Study Group. Prevalence, predictors and co-morbidities of chronic kidney disease among First Nations adults with diabetes: results from the CIRCLE study. BMC Nephrol 2012;13:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agarwal R, Bunaye Z, Bekele DM, et al. Competing risk factor analysis of end-stage renal disease and mortality in chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol 2008;28:569–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Derose SF, Rutkowski MP, Levin NW, et al. Incidence of end-stage renal disease and death among insured African Americans with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2009;76:629–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pavkov ME, Bennett PH, Knowler WC, et al. Effect of youth-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus on end-stage renal disease and mortality in young and middle-aged Pima Indians. JAMA 2006;296:421–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dyck RF, Osgood ND, Gao A, et al. The epidemiology of diabetes mellitus among First Nations and non-First Nations children in Saskatchewan. Can J Diabetes 2012;36:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendelson M, Cloutier J, Spence L, et al. Obesity and type 2 diabetes in a birth cohort of First Nations children born to mothers with pediatric-onset type 2 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 2011;12:219–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parving HH, Hommel E, Smidt UM. Protection of kidney function and decrease in albuminuria by captopril in insulin dependent diabetics with nephropathy. BMJ 1988;297:1086–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]