Abstract

Objective

Determine trends and factors associated with bed-sharing.

Design

National Infant Sleep Position Study: Annual telephone surveys.

Setting

48 contiguous United States.

Participants

Nighttime caregivers of infants born within the last 7 months between 1993 and 2010. Approximately 1000 interviews annually.

Main Outcome Measure

Infant usually bed-sharing.

Results

Of 18,986 participants, 11% reported usually bed-sharing. Bed-sharing increased between 1993 (6.0%) and 2010 (13.5%). While there was an increase for Whites from 1993 to 2000 (p<0.001), there was no significant increase from 2001 to 2010 (p=0.48). Blacks and Hispanics showed increase in bed-sharing throughout the period 1993 to 2010, with no difference between the two time periods (p=0.63 and 0.77, respectively). After accounting for study year, factors associated with increase in usually bed-sharing included: compared to college or more, maternal education less than high school (AOR = 1.4; 95% CI, 1.1–1.8), compared to White race, maternal race or ethnicity Black (AOR = 3.5; 95% CI, 3.0–4.1), Hispanic (AOR = 1.3; 95% CI, 1.1–1.6) and Other (AOR 2.5; 95% CI, 2.0–3.0), compared to household income ≥$50,000, less than $20 000 (AOR = 1.7; 95% CI, 1.4–2.0) and $20–$50,000 (AOR=1.3; 95%CI 1.1–1.5), compared with living in the Midwest, living in the West (AOR=1.6; 95%CI 1.4–1.9) or South (AOR=1.5; 95% CI=1.3–1.7), compared with infant age ≥16 weeks, less than 8 weeks (AOR = 1.5; 95%CI 1.2–1.7 and 8–15 weeks (AOR-1.3; 95% CI=1.2–1.5) and being born prematurely (AOR = 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2–1.6).

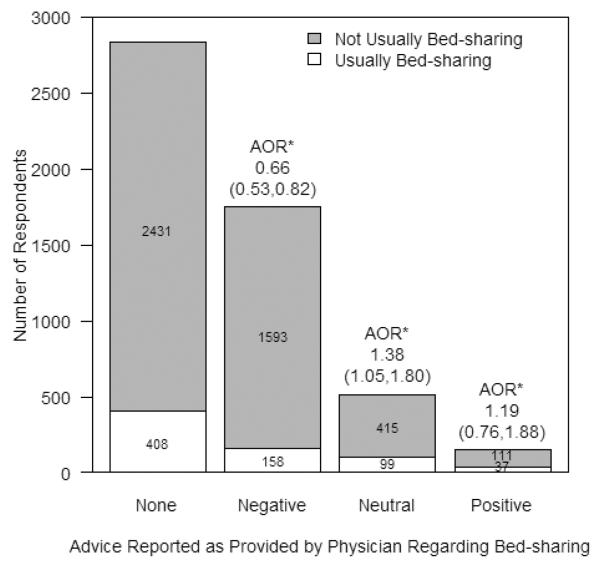

Thirty-six percent of the participants reported talking to a doctor about bed-sharing. Compared with those who did not talk to a doctor, those who reported their doctors had a negative attitude were less likely to bed-share (AOR 0.66 (95% 0.53, 0.82), whereas a neutral attitude was associated with increased bed-sharing. (AOR 1.4; 95%CI 1.1–1.8).

Conclusion

Our findings of the continual increase in bed-sharing throughout the period 1993–2010 among Black and Hispanic infants suggests that the current recommendation about bed-sharing is not universally followed.

Keywords: Bed-sharing, SIDS, racial disparity, infant mortality

Introduction

Bed-sharing is a common practice in many countries including the United States.1, 2 In our previous analysis of the National Infant Sleep Position Study, we found that almost 45% of parents reported sharing a bed with their infants at least some of the time.1 There is a strong association between bed-sharing and both Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS)3,4 and unintentional sleep-related death in infants. Occurrences of unintentional sleep-related deaths appear to be increasing.5

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that infants share a room with parents without sharing a bed when sleeping.6,7 We previously reported that, from 1993–2000, factors associated with usually bed-sharing, included young maternal age, race, geographic region, low income, younger infant age, prematurity, bedding and infant sleeping position.1 The objectives of the current study were to examine trends in infant bed-sharing from 1993 to 2010 with a special focus on how these trends might differ by race/ethnicity; to analyze how the trends have changed over time by comparing trends in the time period from 1993 to 2000 with the data from 2001 to 2010; to describe factors associated with choice to usually bed-share from 1993–2010; and to describe bed-sharing practices according to advice received from a physician.

Methods

The National Infant Sleep Position Study (NISP) Sample

NISP is an annual, cross-sectional study designed to track infant care practices. DataStat, Inc. (Ann Arbor, Michigan) conducted the telephone interviews to home and cellular telephones by randomly sampling targeted households with infants aged 7 months and younger. A representative list taken from the 48 contiguous states was purchased from Metromail (Lincoln, Nebraska). The list was based on public information from sources such as birth records, infant photography companies and formula companies. Telephone numbers were provided by individuals and, for that reason, we do not know if numbers provided were land line or cellular telephone numbers. Interviews were completed if the respondent (the night-time caregiver) answered “yes” to the question, “Is there an infant in the house born in the last 7 months, that is, on or after (date)?” More than 80% of the respondents were the infants' mothers. The goal was to complete approximately 1000 calls each year. The number of calls completed ranged from 1012 to 1188 between 1993 and 2010.

Response rates were calculated using the American Association for Public Opinion Research standard definitions and formulas.8 An exact response rate cannot be calculated because eligibility cannot be determined for those who refused to be interviewed. An estimate of the response rate was made, based on the assumption that the eligible proportion of households who refused is the same as the eligible proportion of those for whom we could determine eligibility. The response rate ranged from 78% in 1993 to 46% in 2010. In 2005, the NISP sample differed from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) National Vital Statistics Report in the following maternal characteristics: race, Black (NCHS 15% vs NISP 6%); Hispanic ethnicity (NCHS 24% vs NISP 6%); younger than 20 years (NCHS 10% vs NISP 3%); and education less than 12 years (NCHS 24% vs NISP 4%).9, 10

Measures

The interview was developed for the NISP study, taking approximately 10 minutes to complete. We asked questions about characteristics of the infants and infant sleep environment including sleeping position, location for sleep and bedding as well as sociodemographics. Participants were asked: “Which of the following best describes the mother's race or ethnic background?” They were then read a list but also given the option to name one that was not listed. Once eligibility was confirmed, an average of 3.5% of the participants did not complete the interview between 1993 and 2010. Non-completion ranged from a low of 2.2% in 2006 to 29.1% in 2010

To elicit information about where infants slept, interviewers read the following scripted questions: “I am going to read a list of places where infants often sleep. After I finish reading the list, please tell me where the infant usually slept at night during the past 2 weeks.” The participant could choose among the following: a crib, a bassinet, a cradle, a carry cot or traveling bed, an adult bed or mattress, a sofa, a playpen, a car or infant seat, or someplace else which they then specified.

Regarding bed-sharing, all respondents were asked, “Does the baby usually sleep alone or share [the usual sleep place] with another person or child?” If the caregiver replied that they share, they were then asked to specify with whom (parent or guardian, another adult, another child). The infant was considered to be usually bed-sharing if the respondent answered that they usually share with another person. We also examined the time that the infant spent on an adult bed (bed-sharing) from the responses usually, half of the time, less than half of the time and never. To determine quilt and comforter use, caregivers were asked if they had usually used a quilt and/or a comforter to cover the infant during the past 2 weeks.

Finally, in 2006, based on the new recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics regarding safe sleep11and the link between physician advice and adherence to safe-sleep recommendations,12,13 we added the following question: “Has a doctor ever talked with you about your baby sleeping in a bed with another person?” For those responding “yes”, we then asked if the doctor's attitude was negative, positive or neutral toward bed-sharing.

Statistical Analysis

The main outcome variable was the participant response that the infant usually shares a bed (or other sleep space) with any other person (bed-sharing). Descriptive statistics were calculated including frequencies and percentages. Trends over time for usually bed-sharing by race/ethnicity were plotted using three year moving averages and tested through the odds ratio for year in logistic regression models. Piece-wise logistic regression models with a term modeling a change in the odds ratio for time were used to test and estimate different trends in bed-sharing from 1993–2000 and from 2001–2010.

Survey year, maternal and infant characteristics, characteristics of the sleep environment and position placed to sleep, were used in univariate logistic regression modeling to determine individual influence of variables on usually bed-sharing, and in a multivariate logistic regression model to determine independent contributions. P Values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted with SAS 9.2 (Statistical Analysis Software 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC.).

This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of Boston University School of Medicine (Boston, MA) and of Yale University School of Medicine (New Haven, CT).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Between 1993 and 2010, 18,986 participants completed the questionnaire, with the goal of approximately 1000 participants each year (ranging from 1012 in 1996 to 1188 in 2002). The median infant age was 131 days, the 10th percentile was 61 days and the 90th percentile was 192 days. These percentiles were similar for each study year. More than 84% of respondents were the mothers of the infants. Almost half of respondents were 30-years old or older, had at least a college education and a yearly income of at least $50,000. More than 80% of the participants were White. (Table 1)

Table.

Adjusted Odds Ratios for Usually Bed-Sharing for 1993–2010 (N=18986)

| Variable | Value | Total | Usually share | Usually share ORs | Usually share Adj. ORs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother's Age | LESS THAN 20 | 910 (4.8) | 179 (19.8) | 2.2 (1.9; 2.7)* | 1.2 (1.0; 1.6) |

| 20 TO 29 | 9067 (48) | 1049 (11.6) | 1.2 (1.1; 1.3)* | 1.0 (0.9; 1.1) | |

| 30 OR MORE | 8925 (47.2) | 891 (10) | |||

| Mother's Education | LESS THAN HS | 1051 (5.5) | 198 (19) | 2.31 (2.0; 2.7)* | 1.4 (1.1; 1.8)* |

| HS/SOME COLLEGE | 9299 (49.1) | 1136 (12.2) | 1.38 (1.3; 1.52)* | 1.1 (1; 1.3) | |

| COLLEGE AND/OR MORE | 8588 (45.3) | 789 (9.2) | |||

| Mother's Race | OTHER | 895 (4.7) | 183 (20.6) | 2.63 (2.2; 3.1)* | 2.5 (2.0; 3.0)* |

| HISPANIC | 1160 (6.1) | 178 (15.4) | 1.85 (1.6; 2.2)* | 1.3 (1.1; 1.6)* | |

| BLACK | 1174 (6.2) | 355 (30.3) | 4.42 (3.9; 5.1)* | 3.5 (3.0; 4.1)* | |

| WHITE | 15757 (83) | 1412 (9) | |||

| First Child | NO | 9678 (51.9) | 1095 (11.3) | 1.1 (1.0; 1.2) | 1.1 (1.0; 1.2) |

| YES | 8962 (48.1) | 963 (10.8) | |||

| US Region | WEST | 2811 (14.8) | 396 (14.1) | 1.7 (1.5; 2.0* | 1.6 (1.4; 1.9)* |

| NEW ENGLAND | 1033 (5.4) | 91 (8.8) | 1.0 (0.8; 1.3) | 1.1 (0.9; 1.4) | |

| MID-ATLANTIC | 2582 (13.6) | 184 (7.1) | 0.8 (0.7; 1.0)* | 0.8 (0.6; 0.9)* | |

| SOUTH | 6651 (35) | 943 (14.2) | 1.7 (1.6; 1.9)* | 1.5 (1.3; 1.7)* | |

| MIDWEST | 5909 (31.1) | 514 (8.7) | |||

| Household Income | LESS THAN $20,000 | 2628 (14.6) | 471 (18) | 2.1 (1.9; 2.5)* | 1.7 (1.4; 2.0)* |

| 20,000 TO $50,000 | 6699 (37.3) | 770 (11.5) | 1.3 (1.2; 1.4)* | 1.3 (1.1; 1.5)* | |

| $50,000 OR MORE | 8619 (48) | 785 (9.1) | |||

| Infant's Age | LESS THAN 8 WEEKS | 1443 (7.8) | 197 (13.7) | 1.4 (1.2; 1.6)* | 1.5 (1.2; 1.7)* |

| 8 TO 15 WEEKS | 5469 (29.7) | 673 (12.3) | 1.2 (1.1; 1.4)* | 1.3 (1.2; 1.5)* | |

| 16 WEEKS OR MORE | 11506 (62.5) | 1182 (10.3) | |||

| Prematurity (<37 weeks) | YES | 2175 (11.5) | 329 (15.2) | 1.5 (1.3; 1.7)* | 1.4 (1.2; 1.6)* |

| NO | 16757 (88.5) | 1791 (10.7) |

95% CIs do not include 1.00 [reference value]

All data adjusted for year of the study

Trends in Usually Bed-Sharing

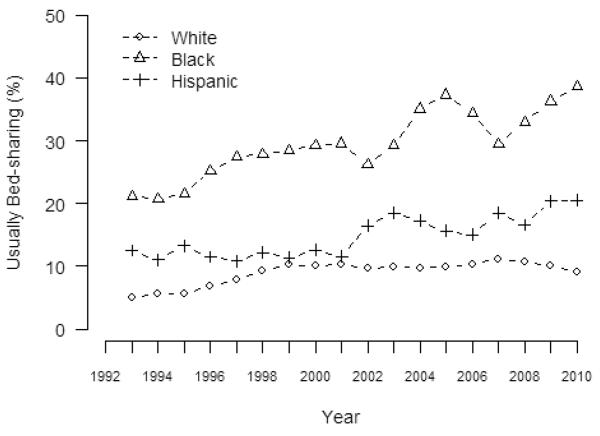

For the years 1993 to 2010, 11.2% (2128/18945) of participants reported that the infants usually shared a bed (or other sleep space). Information about usually bed-sharing was missing for only 41 participants (0.2%). Figure 1 shows the trend over time in usually bed-sharing by race/ethnicity. Each of the racial/ethnic groups showed a significant trend of increasing reports of usually bed-sharing over time between 1993 and 2010. In 1993, 6.5% of all infants usually shared a bed compared with 13.5% in 2010.

Figure 1.

Trends in Usual Bed-Sharing (3-year moving average)

We also performed piece-wise analyses to determine if the trend differed between the periods 1993 – 2000 (the time period that was the subject of our previous publication) compared to the period 2001 – 2010. Among white infants usually bed-sharing increased from 5.2% in 1993 to 9.5% in 2010 (Unadjusted OR 1.04 per year, 95% CI 1.03–1.05, p<0.001), but there was a significant difference in trend over time between the two time periods (p<0.001). During the period from 1993–2000, the odds of bed-sharing increased 1.13 times per year (95%CI, 1.09–1.16), whereas from 2001 – 2010, the rate did not change over time (OR 0.99; 95%CI 0.97–1.01, p=0.48).

This pattern was in contrast to the Black and Hispanic infants for whom there was a progressive increase in usually bed-sharing over time and no difference between the two time periods (p=0.63 and 0.77, respectively). For Black infants the percent usually bed-sharing increased from 24.5% in 1993 to 39.6% in 2010 (OR 1.04 per year, 95%CI 1.02–1.07, p<0.001), and for Hispanic infants the percent usually bed-sharing increased from 5.6% in 1993 to 25.3% in 2010 (OR 1.05 per year, 95%CI 1.02–1.09, p=0.003). Thus, as shown in Figure 1 and from the piecewise regression analysis, we found that there was a widening in the racial gap in bed-sharing between the early time period (1993–2000) and the later time period (2001–2010).

There was a significant increase in the amount of time spent bed-sharing comparing 1993–2000 to the years 2001–2010 (p<0.001). The percentage of caregivers responding that the infant usually shared a bed increased from 8.9% to 10.8%,and half of the time sharing increased from 6.1% to 6.5%. At the same time, the percentage of caregivers responding that the infant never shared a bed decreased from 56% to 54.3%, and less than half of the time sharing decreased from 29% to 28.3%.

Factors Associated with Usually Bed-Sharing

After accounting for the change in bed-sharing over time, factors associated with usually bed-sharing between 1993 and 2010 are shown in Table 1 and include: maternal race/ethnicity (compared to White, AOR = 3.5 for Blacks, AOR = 2.5 for Other, and AOR = 1.3 for Hispanics), maternal education (compared to college graduate, < high graduate AOR = 1.4, household income (compared to an income of $50,000 or more, AOR = 1.7 for income of <$20,000, and AOR of 1.3 for income of $20,000 – $50,000), geographic region (compared the Midwest AOR = 1.6 for the West, AOR = 1.5 for the South, AOR of 0.8 for the mid-Atlantic), infant age (compared to infants 16 or more weeks of age, AOR = 1.5 for infants <8 weeks of age, and AOR = 1.3 for infants 8 – 15 weeks of age), and gestational age at birth (compared to infants born at term, AOR = 1.4 for preterm births). We also compared factors associated with usually bed-sharing separately for the two time periods 1993 –2000 and 2001 – 2010. All of the factors identified in the overall time period were also significantly associated with bed-sharing for the most current time period. For the earlier time period, maternal education and gestational age at birth, did not achieve statistical significance.

In the survey from 2006 and 2010 we added questions as to whether the doctor talked about bed-sharing, and if so, whether the respondent perceived the doctor's attitude as positive (supportive of bed-sharing), negative (against bed-sharing) or neutral. (Figure 2) More than half of the participants reported that they did not get any advice from a physician regarding bed-sharing (2839/5252; 54%). Of those who did receive advice, 73% (1751/2413) reported negative advice, 21% (514/2413) neutral advice and 6% (148/2413) positive advice. Participants who reported that they received negative advice from a doctor were significantly less likely to bed-share than those who received no advice. Positive advice was only reported in 148 of 5252 (3%) participants and did not significantly impact report of bed-sharing. Neutral advice from a doctor was reported by 514 of 5252 (10%) participants, and those participants were significantly more likely to bed-share than those who received no advice at all.

Figure 2.

Doctor Attitude and Participant Report of Bed-Sharing

*AOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio: AOR (95% CI) is for the odds of usually bed-sharing compared to advice

Usually Bed-sharing and Associated Infant Care Practices

Of those who usually shared a bed (or sleep space), 84.7% shared with a parent, 5.1% with an adult other than the parent and 13.6% with another child. These categories were not mutually exclusive. Of those who usually bed-shared, 86.4 % (n=1838) bed-shared on an adult mattress, 9.3% (n=197) in a crib and fewer than 1% in a playpen (n=23) or on a sofa (n=30) Of those who usually slept alone, 71.8% usually slept in a crib, 15.7% a bassinet, 1.4% a car seat, 0.3% in an adult bed or mattress and the rest in other locations.

Reported quilt or comforter use to cover the infant decreased within the early time period, 1993 (41.2%) to 2000 (21.6%) and within the later time period 2001(15.9%) to 2010 (7.8%). Between 1993 and 2010, the proportion of infants reported to be covered by a quilt or comforter decreased from 419/1018 (41%) to 79/1016 (8%) respectively. Compared with 1993 when 31/1027 (3%) of infants who were bed-sharing were also covered by a quilt or comforter, in 2010, 28/1041 (3%) of infants who bed-shared were also covered by a quilt or comforter. Thus the proportion of those infants covered by a quilt or comforter and bed-sharing remained stable between 1993–2010.

Discussion

We found that Black infants, who are at highest risk of SIDS and accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed, are most often bed-sharing. Compared with White infants, Black infants are 3.5 times more likely to bed-share and are more likely than any other race/ethnicity examined in this study to do so. While the trend for White infants to bed-share has not increased in the most recent years, 2001–2010, bed-sharing continues to increase for Black infants.

Lahr et al. published a population-based study using the Oregon Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System finding that 35.2% of mothers reported bed-sharing frequently.14 In 2008, Fu and colleagues examined bed-sharing practices of over 700 mothers at WIC centers across the country that served a predominantly Black population. They found that 32.5% reported bed-sharing last night which is consistent with our data showing that in 2010, 39.6% of Black mothers reported usually bed-sharing.2 In a qualitative study of Black mothers, Joyner and colleagues found that the choice to bed-share was related to convenience, easier vigilance over the infant and, in some cases, as a way to protect their infants from outside dangers.15

As in our previous study, we also found that quilt and comforter use continues to be associated with bed-sharing.1 While fewer caregivers reported quilt or comforter use from 2001–2010 compared with 1993–2001, there remains a strong association between quilt or comforter use and bed-sharing, two behaviors that put infants at risk for sleep-related death.4,16

Public health interventions have been successful in targeting infant sleeping position by motivating more parents to place their infants on their backs to sleep. However, studies have shown that Black infants are less likely to be placed on the back to sleep compared with White and Hispanic infants.13, 17 Changing behaviors can be challenging and our previous work has shown that multiple factors affect parent report of infant care practices such as receiving information from and trust of healthcare providers.12 We have shown that there is an association between receiving advice from a doctor about infant care practices and following this advice.12, 13 However, in the current study we found that many caregivers did not receive any advice from doctors about bed-sharing. If they did receive advice that they should not share a bed with their infants, they were significantly less likely to bed-share. Importantly, we also observed that advice that was perceived as neutral from the physician was associated with more bed-sharing than no advice at all. Given the association between physician advice and bed-sharing and the fact that advice was not reported as uniform and often not reported given at all, it is possible that consistent physician advice in line with recommendations could reduce bed-sharing.

In addition, during the years of the NISP survey, a number of articles were published regarding the risks and benefits of bed-sharing. For example, some studies have shown that bed-sharing is associated with successful breastfeeding, thus supporting bed-sharing.18 Other studies have shown that bed-sharing increases the risk of SIDS, suffocation and strangulation.5 It is possible that during this time families and healthcare providers were receiving mixed messages about the risks of bed-sharing. At this point, however, the weight of the evidence has tipped to the point where the AAP now strongly recommends room-sharing without bed-sharing.6

While this study provides unique data about the trends and factors associated with bed-sharing in the United States, some limitations that should be acknowledged. These data come from the report of the caregiver about what they choose to do related to bed-sharing and may not be the actual practice. Similarly, we included the responses of nighttime caregivers, which could be different from daytime caregivers. However, it is reassuring that our findings are similar to what has been seen in other studies using different samples and methods of data collection.2,14 In addition, the response rate was quite high in the early years of the study, however, consistent with telephone surveys in general, declined substantially in the latter years of the survey. This changing response rate over time, and particularly the relatively low response rate in the latter years, does impact the generalizability of our findings. However, the consistency of our findings over time does suggest that the changing response rate did not have a major impact on our findings. Finally, the sample is not a nationally representative sample when compared with nationally collected vital statistics.10. This is likely due, at least in part, to the known difficulties reaching underrepresented and economically disadvantaged individuals via the telephone for surveys.19 We have attempted to correct for these differences by controlling variables in the multiple logistic regression analysis and by showing prevalence of bed-sharing overtime stratified by race/ethnicity.

Despite these limitations, these data are helpful in understanding trends in bed-sharing, factors associated with bed-sharing and may be useful in evaluating the impact of any broad intervention to change behavior.

Acknowledgements

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. This work was supported in part by funds from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant U10 HD029067-09A1C. Drs. Colson and Corwin had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The following specific contributions were made by the authors:

Study concept and design: Colson, Corwin, Lister, Smith, Willinger

Acquisition of data: Corwin, Hereen, Rybin

Analysis and interpretation of data: Colson, Corwin, Hereen, Lister, Rybin, Smith, Willinger

Drafting of the manuscript: Colson, Corwin

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Colson, Corwin, Hereen, Lister, Rybin, Smith, Willinger

Statistical analysis: Corwin, Hereen, Rybin

Obtaining funding: Corwin

Administrative, technical or material support: Corwin

Study supervision: Colson, Corwin

References

- 1.Willinger M, Ko CW, Hoffman HJ, Kessler RC, Corwin MJ. Trends in infant bed sharing in the United States, 1993–200: the National Infant Sleep Position study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:43–49. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu LY, Colson ER, Corwin MJ, Moon RY. Infant sleep location: Associated maternal and infant characteristics with sudden infant death syndrome prevention recommendations. J Pediatr. 2008;153:503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blair PS, Sidebotham P, Evason-Coombe C, Edmonds M, Heckstall-Smith EM, Fleming P. Hazardous cosleeping environments and risk factors amenable to change: case-control study of SIDS in south west England. BMJ. 2009;339:b3666. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3666. 111/2/e127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vennemann MM, Bajanowski T, Brinkmann B, Jorch G, Sauerland C, Mitchell EA. Sleep environment risk factors for sudden infant death syndrome: the German Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Study. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1162–1170. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Kimball M, Tomashek KM, Anderson RN, Blanding S. US infant mortality trends attributable to accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed from 1984 through 2004: are rates increasing? Pediatrics. 2009;123:533–539. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Policy statement: SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: expansion of recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics. 2011;128:1030–1039. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moon RY, American Academy of Pediatrics. Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Technical report- SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: expansion of recommendations for a safe infant sleep environment. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1341–e1367. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The American Association for Public Opinion Research . Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 7th edition AAPOR; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9. [Accessed October 17, 2012];National Infant Sleep Position Public Access Web Site. http://sloneweb2.bu.edu/ChimeNisp/Main_Nisp.asp.

- 10.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics National Vital Statistics System. Births: final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2007;56(6):1–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.AAP Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome The changing concept of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome: Diagnostic coding, shifts, controversies regarding sleep environment, and new variables to consider in reducing risk. 2005;116:1245–1255. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Von Kohorn IV, Corwin MJ, Rybin DV, Heeren TC, Lister G, Colson ER. Influence of prior advice and beliefs of mothers on infant sleep position. Arch Pediatr and Adolesc Med. 2010;164:363–369. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colson ER, Rybin D, Smith LA, Colton T, Lister G, Corwin MJ. Trends and factors associated with infant sleeping position: the National Infant Sleep Position Study, 1993–2007. Arch Pediatr and Adolesc Med. 2009;163:1122–1128. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lahr MB, Rosenberg KD, Lapidus JA. Bedsharing and maternal smoking in a population-based survey of new mothers. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e530–542. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joyner BL, Oden RP, Ajao TI, Moon RY. Where should my baby sleep: a qualitative study of African American infant sleep location decisions. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102:881–9. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30706-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hauck FR, Herman SM, Donovan M, et al. Sleep environment and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome in an urban population: the Chicago Infant Mortality Study. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5 pt 2):1207–1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauck FR, Moore CM, Herman SM, et al. The contribution of prone sleeping position to the racial disparity in sudden infant death syndrome: the Chicago Infant Mortality Study. Pediatrics. 2002;110(4):772–780. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.4.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKenna JJ, Mosko SS, Richard CA. Bedsharing promotes breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 1997;100:214–219. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skalland BJ, Blumberg SJ. Nonresponse in the national survey of children's health, 2007. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Health Stat. 2012;156:1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]