Abstract

Background

The sacro–iliac joint (SIJ) is the largest joint in the human body. When the lumbar spine is fused to the sacrum, motion across the SIJ is increased, leading to increased degeneration of the SIJ. Degeneration can become symptomatic in up to 75% of the cases when a long lumbar fusion ends with a sacral fixation. If medical treatments fail, patients can undergo surgical fixation of the SIJ.

Questions/Purposes

This study reports the results of short-term complications, length of stay, and clinical as well as radiographic outcomes of patients undergoing percutaneous SIJ fixation for SIJ pain following long fusions to the sacrum for adult scoliosis.

Methods

A retrospective review of all the patients who underwent a percutaneous fixation of the SIJ after corrective scoliosis surgery was performed in a single specialized scoliosis center between the years 2011–2013. Ten SIJ fusions were performed in six patients who failed conservative care for SIJ arthritis. Average age was 50 (range 25–60 years). The patients were 15.3 years in average after the original surgical procedure (range 4–25 years). Average post-operative follow-up was 10.25 months (range 15–4 months). The medical charts of the patients were reviewed for hospital stay, complications, pre- and post-operative pain, quality of life, and satisfaction with surgery using the visual analogues score (VAS), Scoliosis Research Society (SRS)22 and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) questionnaires. Images were reviewed for fixation of the SIJ, fusion, and deviation of the implants from the SIJ.

Results

There were no complications in surgery or post-operatively. Discharge was on post-operative day 2 (range 1–4 days). Leg VAS score improved from 6.5 to 2.0 (P < 0.005; minimal clinically important difference (MCID) 1.6). Back VAS score decreased from 7.83 to 2.67 mm (P < 0.005; MCID 1.2). ODI scores dropped from 22.2 to 10.5 (P = 0.0005; MCID 12.4). SRS22 scores increased from 2.93 to 3.65 (P = 0.035; MCID 0.2) with the largest increases in the pain, function, and satisfaction domains of the questionnaires.

Conclusion

Fixation of the SIJ in patients that fail conservative care for SIJ arthritis after long fusions ending in the sacrum provides a reduction in back pain and improved quality of life in the short and medium range follow-up period.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11420-013-9374-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: sacro–iliac joint, joint fusion, iFuse, SI joint fusion, scoliosis, spine deformity

Introduction

The sacro–iliac joint (SIJ) is the largest joint in the human body; it delivers extreme shear forces that can reach up to 4,800 N [6]. These forces increase when the lumbar spine is fused, leading to increased degeneration of the SIJ. Recent studies have shown that the presence of SIJ degeneration is common in lumbar spine fusion and can reach up to 75% of the cases when a long lumbar fusion ends with a sacral fixation [6]. This degeneration progresses over the years and can appear as early as 2 years after surgery [4].

SIJ pain is a common source of pain; it presents as lower back pain and hip pain and is difficult to distinguish from other types of pelvic girdle pain [2, 16]. The appropriate diagnosis of SIJ pain is by an injection of a local anesthetic to the SIJ alleviating the pain of the patient combined with radiological evidence of osteoarthritis of the joint [7, 9]. Initial treatment options for patients with SI joint pain are physical therapy and pain management; however, in cases that they fail, fixation of the joint is possible [10, 12].

Percutaneous fixation of the SIJ has become more popular over the last years. This minimal invasive surgery uses a small incision over the lateral side of the SIJ, fluoroscopy-guided drilling from the ileum through the SIJ to the sacrum and SIJ fixation with large bore implants. This allows fixation of the joint(s) without the need of a large surgical exposure [8]. However, the procedure has not been described for use in patients that suffer from SIJ degeneration after long spinal fusions.

In this study, we present our initial results of percutaneous SIJ fixation in patients complaining of SI joint pain after long fusion to the sacrum for adult scoliosis. In this analysis, we specifically addressed the incidence of complications and length of hospital stay and the clinical and radiographic outcome of patients undergoing percutaneous SIJ fixation.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective review of all SIJ fusions performed in a single specialized scoliosis center between the years 2011–2013 was performed. Ten fusions were performed in six patients who suffered from pain at the SIJ that was diagnosed by the FABER or compression test and a CT scan showing arthritic changes in the SIJ. Other causes of mechanical pain (pseudoarthorsis or hardware failure) were ruled out. Prior to indicating the percutaneous fusion, all patients had an anesthetic injection into the joint alleviating the pain and had failed to be relieved by 6 months of physical therapy (Table 1). All six patients were female and the average age was 50 ranging from 25–60 years. The patients were 15.3 years in average after the original surgical procedure (range 4–25 years). All fusions extended from the cervical or thoracic spine to the sacrum. The patients had an average of 6.6 previous spinal surgeries performed (range 13–2 previous surgeries). Average post-operative follow-up was 10.25 months (range 4–15 months). Patients who underwent open SIJ fusion or did not undergo a long spine fusion (over six motion segments) ending at the sacrum were excluded from the study.

Table 1.

Review of fusions performed in a single specialized scoliosis center from 2011-2013

| Patient number | Age | Sex | Spine fusion levels | Years from spine fusion | SIJ fused |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | F | T2-S1 | 17 | Right |

| 2 | 57 | F | T12-S1 | 4 | Left |

| 3 | 64 | F | T10-S1 | 11 | Right and left |

| 4 | 24 | F | C7-S1 | 6 | Right and left |

| 5 | 60 | F | T10-S1 | 25 | Right and left |

| 6 | 35 | F | T8-S1 | 20 | Right and left |

The surgical technique has been previously described (Fig. 1) [8, 12]. In our setting, patients are placed under general anesthesia. The patient is placed in the prone position. The lateral buttock and pelvis are draped and prepped using sterile technique. Under fluoroscopic guidance (OEC C-arm) posterior anterior, lateral, outlet, and inlet views are taken of the SIJ. These preliminary views are performed to establish the critical landmarks required for safe insertion of the implants. In the lateral view, superimposition of the sacral ala is needed to achieve a true lateral view of the SIJ. In the outlet view (Ferguson), the neural foramina should be in view. In the inlet view, the anterior wall of the sacrum will appear as one line. In the inlet view the aim is for the outline of the S1 foramen to appear as one line. Adequate visualization of these landmarks is required for safe placement of the screws avoiding both the foramina and intra-spinal canal.

Fig. 1.

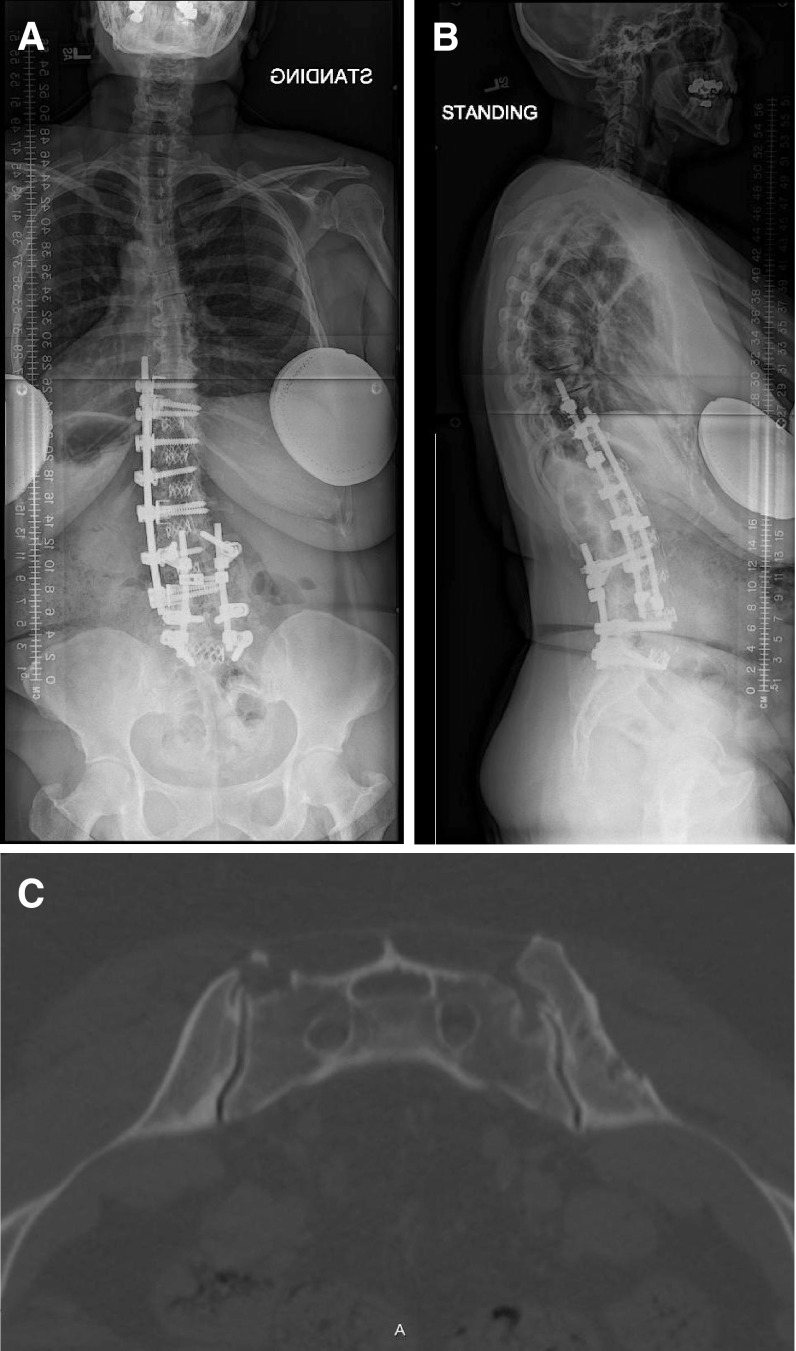

A 67-year-old lady 11 years after spinal fusion from T10 to the pelvis, complained of right sided pain in the posterior pelvis radiating to the hip. On exam, the patient had a positive Faber sign on the right side. A selective injection to the right SIJ alleviated 80% of the patient’s pain. The patient continued to complain of pain despite physical therapy. a Anterior posterior scoliosis view of the patient. b Provides the lateral standing scoliosis view. c Includes the axial CT images of the patient’s SIJ showing bilateral degeneration of the SIJ’s, with narrowing, sclerosis, and osteophytes.

Using a radio–opaque pin, the skin is marked with two lines: the first was along the ala and pelvic brim; the second along the sacrum’s posterior cortical wall for a thin patient and 1–3 cm posterior to the cortical wall in an obese patient. A 3-cm skin incision is made along the second line starting at about 1 cm from the first line. The gluteal fascia is penetrated bluntly and the muscle is split longitudinally to gain access to the outer table of the ilium (Fig. 2). A Steinmann pin is placed on the ilium. As the bifurcation of the descending aorta and the iliac vessels lie anterior to the anterior L5/S1 region, placement of the pin needs to be verified in three planes: lateral, inlet, and outlet. In the lateral view, the pin should be started a centimeter caudal from the S1 endplate and a centimeter off the posterior cortex (Fig. 3). The trajectory of the pin should be parallel to the sacral ala. In the inlet view, angle should be 10–15° elevated from the lateral heading towards the middle of the sacrum (Fig. 4). This angle will avoid penetration of the sacral canal. In the outlet view, the pins should be at least 1 cm from, and parallel to, the S1 endplate.

Fig. 2.

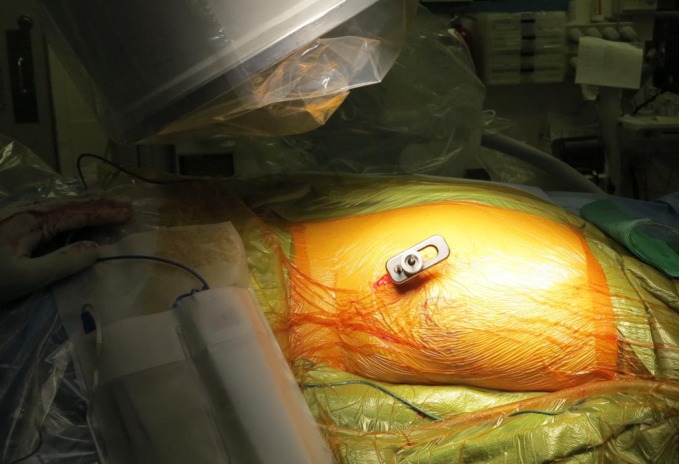

A guide wire is placed via a 3-cm skin incision of the skin.

Fig. 3.

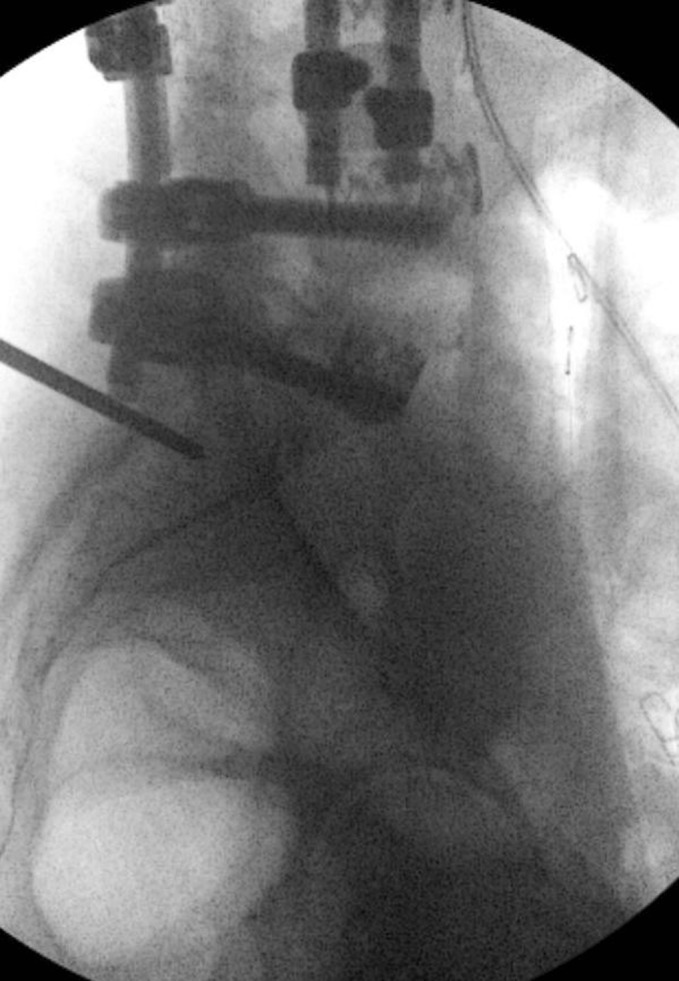

In the lateral view, the pin should be started a centimeter caudal from the S1 endplate and a centimeter off the posterior cortex.

Fig. 4.

In the inlet view, angle should be 10–15° elevated from the lateral heading towards the middle of the sacrum.

The pin is advanced across the SI joint into the lateral portion of the sacrum (Denis zone I [3] and lateral to the neural foramen. A depth gauge is used to determine implant length. Through the cannulated tissue protector, the bone is prepared using a drill and triangular broach before the implant is inserted. The cephalad implant is routinely placed within the sacral ala. A pin-guide system is used to facilitate placement of the subsequent implants (Figs. 5 and 6). The second implant is generally located above or adjacent to the S1 foramen and the third between the S1 and S2 foramen. Implant location must be verified using fluoroscopy. The incision is then irrigated and the tissue layers are closed and the wound is dressed. The procedure typically requires 1 to 2 h in the operating room with minimal blood loss.

Fig. 5.

A clinical picture of the pin-guide system that is used to place the second x-wire in parallel to the first implant.

Fig. 6.

A inlet fluoroscopy image, showing the pin-guide system; the second pin is placed in parallel to the first implant.

In this series, a triangular iFuse titanium implant was used (SI-BONE, San Jose, CA). Biomechanical studies demonstrated that the implant is three times stronger in shear and bending strength compared to an 8-mm cannulated screw (SI-BONE Inc. data on file). Implants are available in either a 4.0 or 7.0-mm inscribed diameter and in 5-mm incremental lengths from 30 to 70 mm to fit individual patient anatomy.

Post-operatively, patients were instructed to protect weight bearing for 2 weeks after surgery, walking with crutches or a walker (approximately 80 lbs). Patients were discharged from the hospital as soon as they cleared physical therapy and pain was controlled allowing proper mobilization at home.

Patients were followed in the outpatient deformity clinic post-operatively at 2 and 6 weeks, 3 and 6 months, and 1 and 2 years after the procedure. In cases that patients missed a follow-up appointment, a “catch-up” appointment was scheduled. Questionnaires were passed to the patients by the research coordinator of the clinic (TR). Back and leg pain was assessed using the visual analogues score (VAS), quality of life was assessed with the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) and the Scoliosis Research Society (SRS)22 questionnaires. The medical charts of the patients were reviewed for hospital stay (days in hospital), complications, pre- and post-operative pain (VAS), and quality of life (ODI and SRS22).

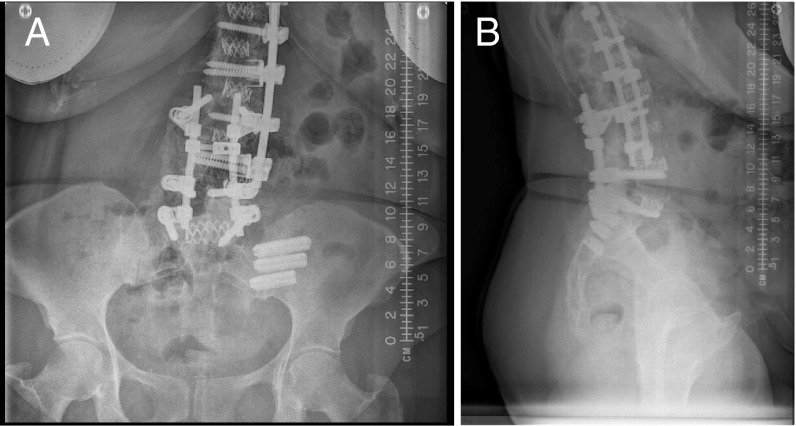

Images were reviewed by a fellowship-trained spine surgeon (JES) for successful fusion defined as a bone bridge across the SIJ in an axial or coronal CT scan or on two x-ray views. Radiographs were also studied to document safe position of the implants noting any penetration out of the bone elements of the SIJ or for any sign of lucency around the implants suggesting loosening of the implants (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

AP (a) and lateral (b) images of the patient post-operative showing the implants position across the SIJ.

The data were analyzed using Excel office software (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t test for independent variables. The threshold for statistical significance was established at P < 0.05.

Results

There were no complications in surgery or in the post-operative period and patients were discharged on average on the second post-operative day (range 1–4 days). All patients experienced important clinical improvement compared to their pre-operative condition. Spine VAS score improved from a pre-operative leg average pain level of 6.5 to 2.0 post-operative pain level (P < 0.005; MCID 1.6). Back VAS score decreased from an average of 7.83- to a 2.67-mm post-operative pain level (P < 0.005; MCID 1.2). ODI scores dropped from an average of 22.2 to 10.5 post-operatively (P = 0.0005; MCID 12.4). SRS22 scores increased from a 2.93 average to 3.65 (P = 0.035; MCID 0.2) with the largest increases in the pain, function, and satisfaction domains of the questioner (NS) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in scores pre- and post-surgery

| Score | Pre-surgery value | Post-surgery | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VAS spine | 7.83 | 3 | P < 0.005 |

| VAS leg | 6 | 2.66 | P < 0.005 |

| ODI | 22.1 | 10.5 | P < 0.005 |

| SRS22 | 2.93 | 3.65 | P = 0.03 |

| Function | 2.7 | 3.4 | NS |

| Pain | 1.8 | 3.1 | NS |

| Self image | 3 | 3.8 | NS |

| Mental health | 3.86 | 4.2 | NS |

| Satisfaction | 3.7 | 4.25 | NS |

All implants were placed in across the SIJ, without breaching medially into the pelvis or into the foramina. There was no lucency around the implants or any movement of the implants in the latest follow-up, indicating that there was no loosening of the implants. Bony bridging could be seen in four patients at the time of the last follow-up.

Discussion

SIJ pain is a common cause of morbidity after long fusion to the pelvis. Its prevalence increases over time and causes back and hip pain [6]. In this study, our aim was to judge the success of percutaneous SI joint fusion in patients after a long spine fusion ending at the sacrum who suffered from SIJ pain negatively affecting their quality of life as evidenced by high ODI and low SRS22 scores. This minimally invasive technique to fuse the SIJ resulted in a significant decrease in back and hip pain.

The limitations of the study are its retrospective nature, its short duration, and the small number of patients. Also, the images were only reviewed by a single reviewer.

The classical technique for sacroiliac joint fusion was described by Smith-Petersen [14]. He used a large open posterolateral approach with graft insertion through a window cut in the lateral side of the ilium. Verral and Pitkin advanced these techniques by removing the cartilage of the joint and impaction of cancellous bone in the SIJ [13]. Using a long allogeneic tibial bone-graft, they built a bridge between the posterior parts of both iliac wings, crossing the sacrum dorsally. These open techniques, even when modified to more modern fixation devices, are associated with increased blood loss and surgical time, and have mixed results [8, 13].

In contrast, Rudelf [12] reported on a cohort of 50 patients that underwent percutaneous fusion for SIJ arthritis, not associated with spine pathology. A favorable clinical outcome was achieved with 82% experiencing a clinically significant benefit at 40 months. Mean improvements in quality of life measures were statistically and clinically significant at all-time points.

There is only a limited data regarding fixation of the SIJ in deformity cases. Bridwell et al., [1] when discussing fusion to the sacrum versus stopping at the L5 vertebrae stated that exposing the sacrum adds length and morbidity to the surgery, as more dissection is required. Other than the risks for nonunion and dural tears, fixation to the sacrum may alter the mechanics of the patient’s gait, and cause subsequent degeneration of the sacroiliac joints, which, had not been clinically realized as a major problem [14]. Recently, multiple publications document that after a lumbar spine fusion ending at the sacrum, the increased mobility and forces through the SIJ lead to increased SI joint pain requiring treatment [6, 11, 12, 15]. This study is the first to address the surgical treatment for the SIJ arthritis years after a spine fusion ending at the sacrum. The combination of percutaneous insertion of a triangular titanium implant combined with an osteogenic interference fit used in this study is designed to minimize rotation, micromotion, and avoid issues often seen with orthopedic screws, such as loosening and breakage [6]. Reduction of pain is achieved by eliminating SI joint motion. The implant surface is prepared with a porous plasma spray coating that encourages bone-on-growth across the joint, resulting in permanent fusion to the implants. Four of six patients showed bone bridging at the latest follow-up and we expect to see fusion in longer term follow-up.

In conclusion, percutaneous fixation of the SIJ in patients that fail conservative care for SIJ arthritis after long fusions ending in the sacrum provides a reduction in back pain and improved quality of life over the short-term (10 month) follow-up of this study.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 1224 kb)

(PDF 336 kb)

(PDF 1225 kb)

(PDF 1225 kb)

Disclosures

Conflict of Interest: Josh E. Schroeder, MD declares that he has no conflict of interest. Matthew E. Cunningham, MD, PhD reports personal fees from DePuy and J&J, outside the work. Tom Ross, RN reports grants from DePuy Synthes Spine, during the conduct of the study. Oheneba Boachie-Adjei, MD reports grants from DePuy Synthes Spine during the conduct of the study; is a consultant for DePuy, K2M, OsteoTech, and Trans1; receives grants from DePuy, K2M, and OsteoTech; other from DePuy, K2M, and Trans1; receives travel expenses and research support from K2M, outside the submitted work. In addition, Dr. Boachie-Adjei, MD has a patent with K2M and receives royalties from patents from DePuy and K2M.

Human/Animal Rights: All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008 [5].

Informed Consent: Informed consent was waived from all patients for being included in the study.

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

Footnotes

Level of Evidence: Level IV: Therapeutic Study

References

- 1.Bridwell KH, Edwards CC, 2nd, Lenke LG. The pros and cons to saving the L5-S1 motion segment in a long scoliosis fusion construct. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28(20):S234–S242. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000092462.45111.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen SP. Sacroiliac joint pain: a comprehensive review of anatomy, diagnosis, and treatment. Anesth Analg. Nov 2005; 101(5): 1440-1453. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Denis F, Davis S, Comfort T. Sacral fractures: an important problem. Retrospective analysis of 236 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. Feb 1988; 227: 67-81. [PubMed]

- 4.DePalma MJ, Ketchum JM, Saullo TR. Etiology of chronic low back pain in patients having undergone lumbar fusion. Pain Me. 12(5):732-739. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Frymoyer JW, Howe J, Kuhlmann D. The long-term effects of spinal fusion on the sacroiliac joints and ilium. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1978;134:196–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ha KY, Lee JS, Kim KW. Degeneration of sacroiliac joint after instrumented lumbar or lumbosacral fusion: a prospective cohort study over five-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33(11):1192–1198. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318170fd35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansen HC, McKenzie-Brown AM, Cohen SP, Swicegood JR, Colson JD, Manchikanti L. Sacroiliac joint interventions: a systematic review. Pain Physician. Jan 2007; 10(1): 165-184. [PubMed]

- 8.Kim JT, Rudolf LM, Glaser JA. Outcome of percutaneous sacroiliac joint fixation with porous plasma-coated triangular titanium implants: an independent review. Open Orthop J. 7:51-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Maigne JY, Planchon CA. Sacroiliac joint pain after lumbar fusion. A study with anesthetic blocks. Eur Spine J. 2005;14(7):654–658. doi: 10.1007/s00586-004-0692-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maigne JY, Aivaliklis A, Pfefer F. Results of sacroiliac joint double block and value of sacroiliac pain provocation tests in 54 patients with low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996;21(16):1889–1892. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199608150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohtori S, Sainoh T, Takaso M, et al. Clinical incidence of sacroiliac joint arthritis and pain after sacropelvic fixation for spinal deformity. Yonsei Med J. 53(2):416-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Rudolf L. Sacroiliac joint arthrodesis-mis technique with titanium implants: report of the first 50 patients and outcomes. Open Orthop J. 6:495-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Schutz U, Grob D. Poor outcome following bilateral sacroiliac joint fusion for degenerative sacroiliac joint syndrome. Acta Orthop Belg. Jun 2006; 72(3): 296-308. [PubMed]

- 14.Smith-Petersen MN. Arthrodesis of the sacroiliac joint, a new method of approach. J Bone Joint Surg. 1921;3(8):400–405. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuchiya K, Bridwell KH, Kuklo TR, Lenke LG, Baldus C. Minimum 5-year analysis of L5-S1 fusion using sacropelvic fixation (bilateral S1 and iliac screws) for spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31(3):303–308. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000197193.81296.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshihara H. Sacroiliac joint pain after lumbar/lumbosacral fusion: current knowledge. Eur Spine J. 21(9):1788-1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 1224 kb)

(PDF 336 kb)

(PDF 1225 kb)

(PDF 1225 kb)