Biosynthesis of the amino acid serine occurs mainly via photorespiration in plants. This work shows, however, that locally restricted serine biosynthesis via the alternative phosphoserine pathway is required for proper embryo development and leaf initiation, highlighting the importance of cellular resolution when analyzing metabolic pathways.

Abstract

In plants, two independent serine biosynthetic pathways, the photorespiratory and glycolytic phosphoserine (PS) pathways, have been postulated. Although the photorespiratory pathway is well characterized, little information is available on the function of the PS pathway in plants. Here, we present a detailed characterization of phosphoglycerate dehydrogenases (PGDHs) as components of the PS pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. All PGDHs localize to plastids and possess similar kinetic properties, but they differ with respect to their sensitivity to serine feedback inhibition. Furthermore, analysis of pgdh1 and phosphoserine phosphatase mutants revealed an embryo-lethal phenotype and PGDH1-silenced lines were inhibited in growth. Metabolic analyses of PGDH1-silenced lines grown under ambient and high CO2 conditions indicate a direct link between PS biosynthesis and ammonium assimilation. In addition, we obtained several lines of evidence for an interconnection between PS and tryptophan biosynthesis, because the expression of PGDH1 and PHOSPHOSERINE AMINOTRANSFERASE1 is regulated by MYB51 and MYB34, two activators of tryptophan biosynthesis. Moreover, the concentration of tryptophan-derived glucosinolates and auxin were reduced in PGDH1-silenced plants. In essence, our results provide evidence for a vital function of PS biosynthesis for plant development and metabolism.

INTRODUCTION

Ser is an important amino acid that is an essential constituent of proteins, and is also a substrate for the biosynthesis of phosphatidylserine (Vance and Steenbergen, 2005; Nerlich et al., 2007), Trp (Tzin and Galili, 2010), and Trp-derived secondary metabolites such as auxin, indolic glucosinolates, and camalexin (Glawischnig et al., 2000; Gigolashvili et al., 2007; Sazuka et al., 2009; Vernoux et al., 2010). Furthermore, Ser functions as an important single-carbon (C1) donor in tetrahydrofolate (THF) metabolism in plants (Hanson and Gregory, 2002; Rébeillé et al., 2007). Therefore, appropriate levels of Ser for each of these metabolic pathways have to be maintained in almost all tissues to ensure proper plant development.

In plants, photorespiration is thought to be the main route of Ser biosynthesis (Bauwe et al., 2010; Maurino and Peterhansel, 2010). Photorespiration, as a consequence of the oxygenase reaction of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, results in one molecule of 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PGA) and one molecule of 2-phosphoglycolate (2-PG). Via multiple reactions residing in chloroplasts and peroxisomes, 2-PG is converted to Gly, which is then metabolized to Ser in mitochondria by a glycine decarboxylase complex (GDC) and a serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT), using THF as a coenzyme (Figure 1). Photorespiratory Ser biosynthesis requires photosynthesis and is thus restricted to photosynthetic tissues. Although plants are able to reallocate amino acids from source to sink tissue via the phloem (Winter et al., 1992), it remains unclear whether nonphotosynthetic cells can be sufficiently supplied with amino acids by phloem-mediated transport.

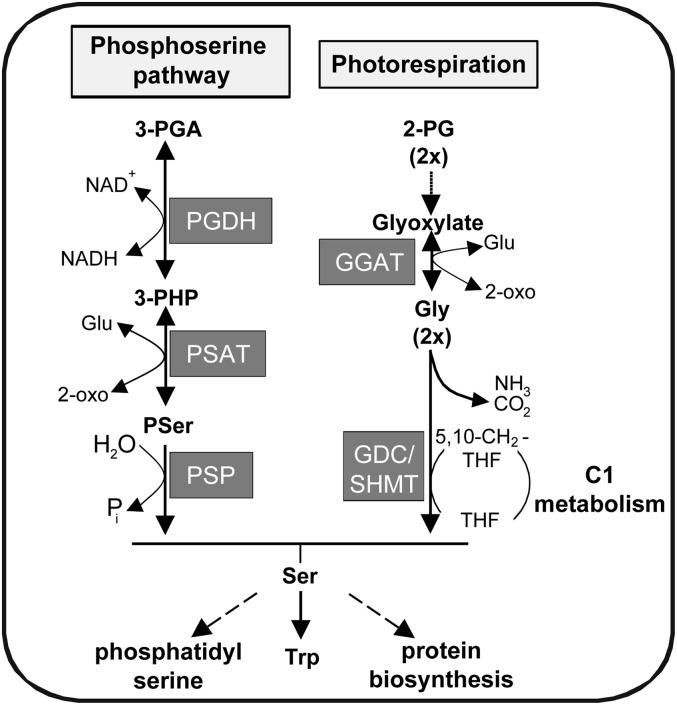

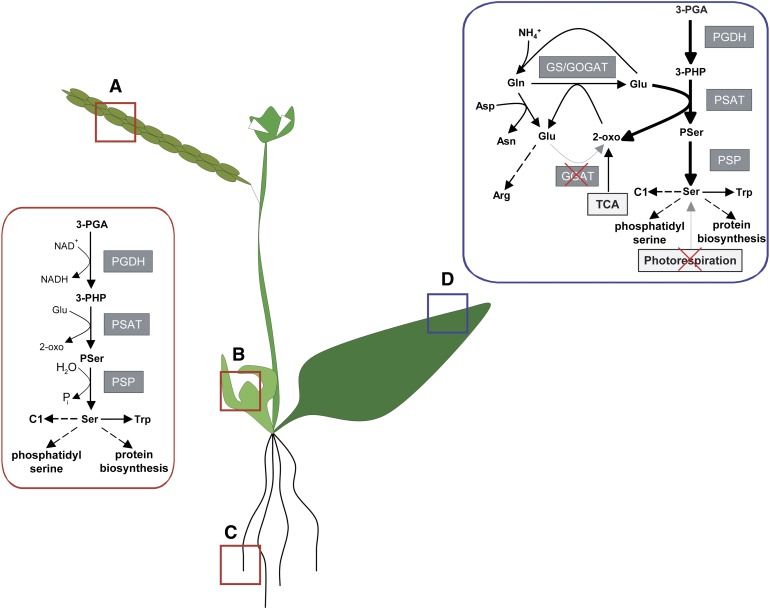

Figure 1.

Ser Biosynthesis Pathways in Plants.

Ser can be synthesized by two major pathways: the PS pathway and the photorespiration pathway. The PS pathway starts with the oxidation of 3-PGA catalyzed by PGDH, yielding 3-PHP and reduced NADH. Phosphoserine (PSer) is synthesized by the transfer of an amino group from Glu to 3-PHP by PSAT. Finally, PS is dephosphorylated to Ser by PSP. Photorespiratory Ser biosynthesis starts with the synthesis of 2-PG by the oxygenase activity of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. 2-PG is converted to Gly by several enzymatic reactions occurring in chloroplasts and peroxisomes. In mitochondria, Ser is synthesized from two molecules of Gly catalyzed by the GDC and SHMT. GDC catalyzes the decarboxylation of Gly by releasing CO2 and NH3, yielding one molecule of 5,10-CH2-THF. Finally, Ser is synthesized by the transfer of the methyl group of 5,10-CH2-THF to an additional molecule of Gly, catalyzed by the SHMT enzyme.

The genomes of several plant species encode enzymes for an alternative pathway of Ser biosynthesis, the glycolytic or phosphoserine (PS) pathway (Slaughter and Davies, 1968; Larsson and Albertsson, 1979; Ho and Saito, 2001). In prokaryotes and mammals, Ser is synthesized predominantly via the PS pathway using 3-PGA (Pizer, 1963; McKitrick and Pizer, 1980; Snell, 1984; Achouri et al., 1997; Dey et al., 2005), whereas in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), Ser can be produced either by the PS or the gluconeogenic pathway, depending on the available carbon source (Melcher and Entian, 1992; Sinclair and Dawes, 1995).

The PS pathway consists of three enzymatic reactions (Figure 1). Initially, 3-PGA is reversibly oxidized to 3-phosphohydroxypyruvic acid (3-PHP) by phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PGDH). Subsequently, 3-PHP is converted by phosphoserine aminotransferase (PSAT) to PS and 2-oxoglutarate, using Glu as an amino group donor, and finally to Ser by a phosphoserine phosphatase (PSP). In Arabidopsis thaliana, PGDH activity is encoded by three loci (PGDH1 [At4g34200], PGDH2 [At1g17745], and PGDH3 [At3g19480]) and PSAT activity by two loci (PSAT1 [At4g35630] and PSAT2 [At2g17630]), whereas PSP is present as a single copy gene (PSP [At1g18640]).

RNA gel blot analysis and in situ hybridization of some of the PS pathway genes in Arabidopsis indicate a function of the pathway in both heterotrophic and autotrophic tissues (Ho et al., 1998, 1999a, 1999b; Ho and Saito, 2001). Furthermore, inhibition of de novo Ser biosynthesis was not complete in plants grown under nonphotorespiratory conditions by either transferring them to high CO2 conditions (Agüera et al., 2006; Pick et al., 2013) or inhibiting glycolate oxidase, a photorespiratory enzyme (Servaites, 1977). Therefore, the presence of an additional pathway for the biosynthesis of Ser in plants was postulated.

Although the PS pathway is apparently present in plants, its significance for plant metabolism has remained elusive. Here, we report a detailed characterization of the Arabidopsis PGDH isoenzyme family, which encode the initial and rate-limiting enzyme of the PS pathway. Our data demonstrate that all putative PGDH isoenzymes possess PGDH activity, are partly regulated by Ser feedback inhibition, and are located within plastids. Moreover, loss-of-function mutants for PGDH1 and PSP are embryo lethal, indicating that the PS pathway is essential for plant viability. In addition, analyses of PGDH1-silenced plants indicate an important function of the PS pathway in plant development, ammonium assimilation, and the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites.

RESULTS

PGDH Isoenzymes Localize Exclusively to Plastids

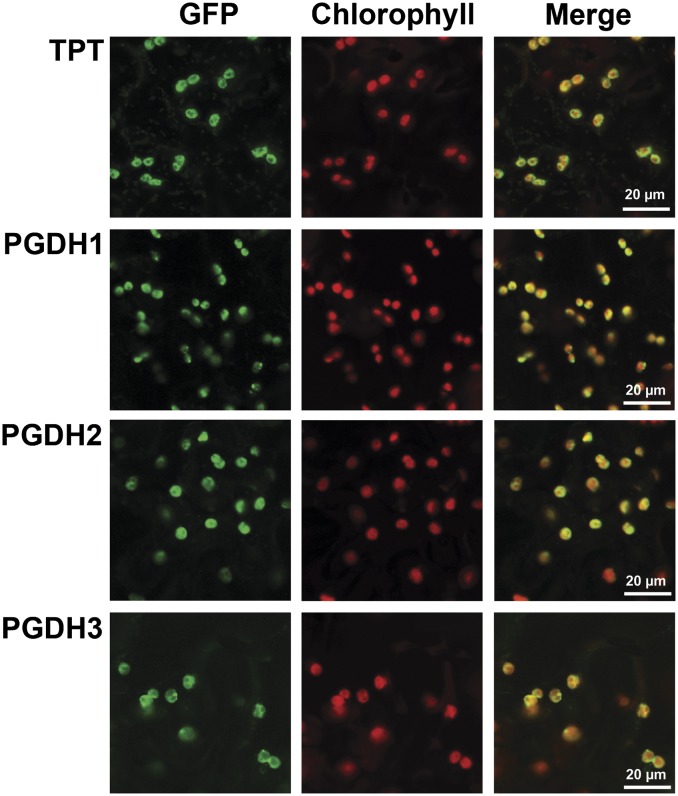

According to in silico predictions, all Arabidopsis PGDH isoenzymes possess putative plastidic transit peptides (ARAMEMNON database, http://aramemnon.botanik.uni-koeln.de; Schwacke et al., 2003). Previous studies investigating C-terminal green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion proteins indicated a plastidic localization of PGDH2 (Ho et al., 1999a). However, the in vivo localization of the more highly expressed PGDH1 and the weakly expressed PGDH3 isoform (eFP-Browser, http://bar.utoronto.ca/efp/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi; Winter et al., 2007) have not yet been clarified. To study the subcellular localization of PGDHs, we investigated GFP fusion proteins by expressing PGDH full-length coding regions and sequences encoding putative plastid target peptides predicted by the TargetP 1.1 program (Emanuelsson et al., 2007) transiently in Nicotiana benthamiana. Localization of the fusion proteins was compared with chlorophyll autofluorescence as well as with localization of the chloroplastidic triosephosphate/phosphate translocator fused to GFP (Flügge and Heldt, 1976). Analyses showed that the full-length fusion protein of PGDH1 was clearly targeted to the chloroplast, because the GFP signal and chlorophyll autofluorescence colocalized (Figure 2). However, no or only weak GFP fluorescence was detected in plastids of heterotrophic and autotrophic tissue of plants transformed with genes encoding full-length PGDH2 or PGDH3-GFP fusion proteins. Therefore, GFP fusions with the putative N-terminal target peptides of PGDH2 and PGDH3 were analyzed instead. Both putative target peptides clearly directed GFP to the chloroplast (Figure 2), confirming the plastidic localization of both enzymes.

Figure 2.

Subcellular Localization of Arabidopsis PGDH Isoenzymes in Transiently Transfected N. benthaminana Leaves.

For each of the PGDH isoenzymes, fusion proteins with GFP were generated and transiently expressed in N. benthaminana leaves under the control of the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter. Chlorophyll autofluorescence and the fluorescence signal of the transiently expressed TPT:GFP fusion protein were used as a marker for chloroplastic localization. TPT, triosephosphate/phosphate translocator.

PGDH Isoenzymes Are Differentially Regulated via Ser Feedback Inhibition

To determine substrate affinity and feedback regulation of Arabidopsis PGDH isoenzymes, truncated versions of all three genes lacking putative target peptide sequences were cloned into the pET16b vector (Novagen). The constructs containing an N-terminal 6 × His-tag were expressed in Escherichia coli and the fusion proteins were purified using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) affinity chromatography. Purification of PGDH enzymes to near homogeneity was confirmed by SDS-PAGE analysis (see Supplemental Figure 1 online). Because plant PGDH enzymes might be active in chloroplasts as well as in heterotrophic plastids, the catalytic properties were determined at the physiological pH conditions present in the stroma of illuminated chloroplasts, pH 8.1, or plastids of heterotrophic tissue, pH 7.2 (Heldt et al., 1973; Werdan et al., 1975).

The three Arabidopsis PGDH enzymes exhibited typical Michaelis–Menten kinetics (see Supplemental Figure 2 online), with higher specific activities and turnover (kcat) at pH 8.1 compared with pH 7.2 (Table 1). Whereas the Km for 3-PGA was higher at pH 7.2 compared with at pH 8.1, the Km for nicotinamide dinucleotide (NAD+) was only slightly higher for PGDH2 and PGDH3 and almost unchanged for PGDH1 in more alkaline conditions. Notably, the Km values for 3-PGA and NAD+ as well as the Vmax value and turnover number were of the same magnitude for all PGDH isoenzymes (Table 1).

Table 1. Biochemical Properties of the Three Arabidopsis PGDH Enzymes.

| Enzyme | pH | Vmax (U⋅mg−1) | kcat (s−1) |

Km (mM) |

Efficiency kcat/Km (M−1⋅s−1) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-PGA | NAD+ | 3-PGA | NAD+ | ||||

| PGDH1 | 8.1 | 165.0 | 174.1 | 1.308 | 0.390 | 133,112.8 | 446,325.5 |

| 7.2 | 109.1 | 115.1 | 2.110 | 0.377 | 54,572.8 | 305,677.1 | |

| PGDH2 | 8.1 | 133.0 | 147.4 | 0.899 | 0.189 | 153,974.5 | 780,115.9 |

| 7.2 | 108.0 | 119.7 | 1.926 | 0.271 | 62,162.4 | 442,605.3 | |

| PGDH3 | 8.1 | 137.6 | 142.4 | 1.006 | 0.239 | 141,600.4 | 595,029.1 |

| 7.2 | 93.7 | 97.0 | 2.559 | 0.551 | 37,914.9 | 176,151.6 | |

For characterization of the PGDH enzyme, kinetic properties such as Vmax and Km values for 3-PGA and NAD+ were determined at two different pH values. The turnover number (kcat) and the catalytic efficiency of the enzymes were calculated.

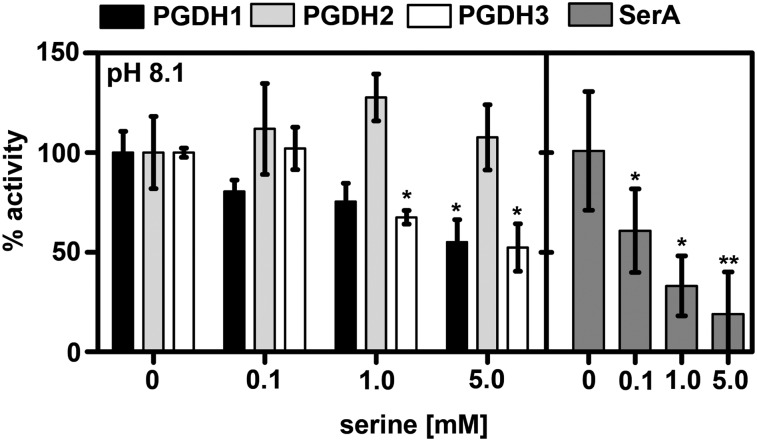

In several organisms, PGDH activity is negatively regulated by Ser binding to the so-called ACT domain, which is present in all known PGDH enzymes (Grant, 2006). The ACT domain is a regulatory domain named after the bacterial enzymes Aspartate kinase, Chorismate mutase and TyrA (prephenate dehydrogenase) in which this domain was first identified. To investigate a possible negative feedback regulation of Arabidopsis PGDH enzymes, their specific activity was determined in the presence of different Ser concentrations. In the presence of 100 µM Ser, the specific activity of SerA, the well-studied E. coli PGDH used as a control, was reduced to ∼60%, whereas the activities of the Arabidopsis enzymes were not significantly altered (Figure 3). However, the activity of PGDH3 was decreased at 1 mM Ser and that of PGDH1 at 5 mM Ser. By contrast, PGDH2 activity was completely unaffected at any Ser concentration tested (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Ser Feedback Inhibition of PGDH Isoenzymes of Arabidopsis.

Feedback sensitivity of the respective PGDH enzymes against different concentrations of Ser (0 to 5 mM) was tested. The values represent the percentage activity in the presence of Ser compared with the nontreated control (0 mM Ser). The mean of eight replicates is shown, and error bars indicate the sd. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01.

Organ- and Tissue-Specific Expression Patterns of PGDH Isoenzymes

According to publicly available microarray data (eFP-Browser, http://bar.utoronto.ca/efp/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi; Winter et al., 2007; https://www.genevestigator.com, Zimmermann et al., 2004), PGDH1 is the most highly expressed isoform in root and shoot tissues, followed by PGDH2. The third isoform, PGDH3, is only weakly expressed. However, tissue-specific expression data are not available for Arabidopsis PGDHs. Therefore, we analyzed plants expressing the β‑glucuronidase (GUS) reporter gene under control of the native PGDH promoters.

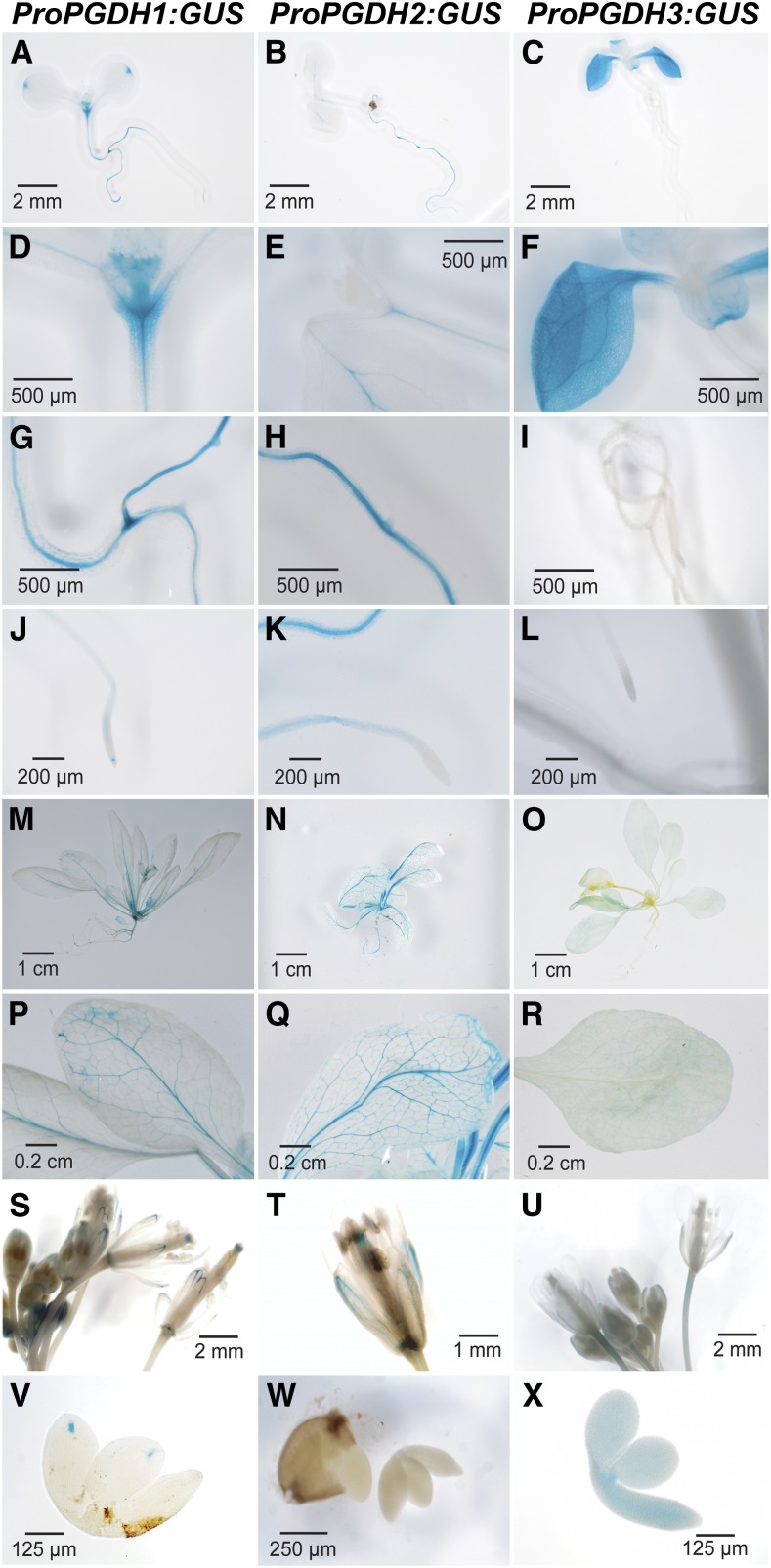

In 10-d-old seedlings, each of the three PGDHs displayed distinct expression patterns (Figures 4A to 4I). PGDH1 is highly expressed at the tips of the cotyledons, within the shoot apical meristem (SAM), within the vasculature of leaves and roots, at points of lateral root emergence, and within the root apical meristem (RAM) (Figures 4A, 4D, 4G, and 4J). PGDH2 is expressed within the vasculature of the shoot and in the SAM, but expression is more pronounced in the vasculature of the root. However, PGDH2 expression was not detected within the RAM (Figures 4B, 4E, 4H, and 4K). By contrast, PGDH3 is strongly expressed in the cotyledons of 10-d-old seedlings and weakly expressed in leaves, but is completely absent from the roots and meristematic tissue (Figures 4C, 4F, 4I, and 4L).

Figure 4.

Histochemical Staining of GUS Activity in Plants Expressing ProPGDH1:GUS, ProPGDH2:GUS, and ProPGDH3:GUS Constructs.

(A) to (C) Ten-day-old seedlings.

(D) to (F) Meristematic tissue in shoots of 10-d-old seedlings.

(G) to (I) Primary and lateral roots of mature plants.

(J) to (L) Root tip of mature plants.

(M) to (O) Rosettes of mature plants.

(P) to (R) Rosette leaves of mature plants.

(S) to (U) Flowers.

(V) to (X) Embryos.

In mature plants, PGDH1 and PGDH2 showed strongly overlapping expression domains in the vascular tissue of leaves and roots (Figures 4M, 4N, 4P, and 4Q). In addition, both genes were expressed in the petal vasculature, and in the style, and base of the siliques (Figures 4S and 4T).

Although expression of PGDH1 and PGDH2 was high in vegetative tissues, no GUS activity was detected at the early stages of embryo development. However, during late embryo development, PGDH1 showed specific expression at the tips of the cotyledons, whereas PGDH2 was not expressed at all at this stage (Figures 4V and 4W). In contrast with PGDH1 and PGDH2, PGDH3 showed a very weak but uniform expression in the embryo (Figure 4X).

Deficiency in PS Biosynthesis Impairs Embryo and Plant Development

To investigate the importance of the PS pathway for plant development and viability, T-DNA insertion mutants for PGDH1, PGDH2, and PSP were isolated. Two allelic homozygous lines were identified for PGDH2 (pgdh2_1 [SALK_069543] and pgdh2_2 [SALK_149747]), but we were unable to isolate plants homozygous for a T-DNA insertion in either PSP or PGDH1 from two independent lines for each locus (SALK_062391 [psp–1/+] and SAIL_658_A06 [psp–2/+], SAIL_209_G08 [pgdh1–1/+], and GK_155B09 [pgdh1–2/+]). Further analyses of the two allelic PGDH2 mutants revealed no discernible mutant phenotype (see Supplemental Figures 3 and 4 online).

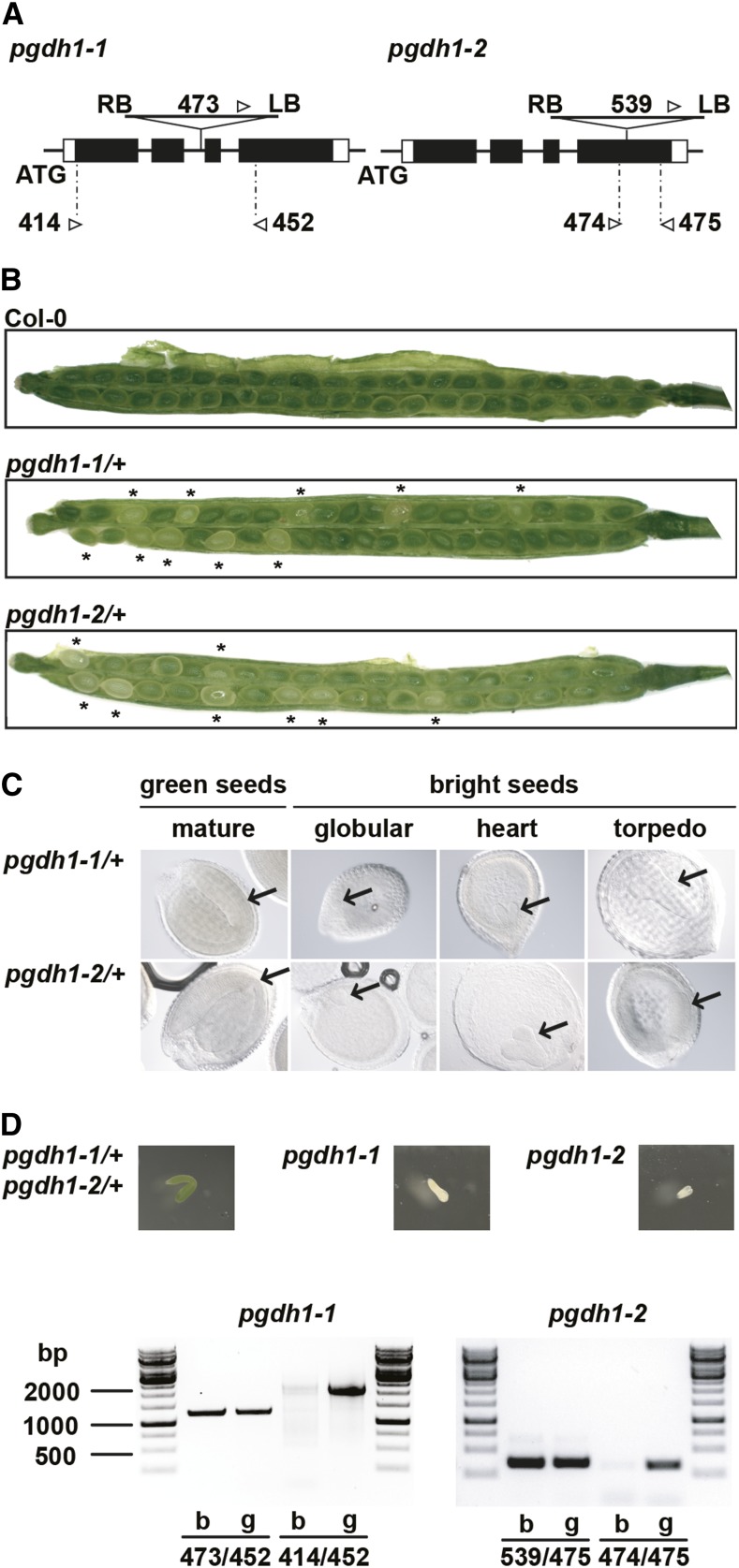

Because no homozygous lines could be isolated for PGDH1 and PSP, we analyzed seed maturation in siliques of pgdh1–1/+, pgdh1–2/+, psp–1/+, and psp–2/+ 12 to 14 d after flowering (Figures 5A to 5D; see Supplemental Figures 5A to D online). Siliques of the heterozygous pgdh1 and psp lines contained nongreen, translucent seeds in addition to normally developed green seeds (Figure 5B). Microscopic analyses of these seeds revealed arrest of embryo development at early stages ranging from the globular to the torpedo stage (Figure 5C; see Supplemental Figures 5B and 5C online). Further analysis of isolated embryos by PCR-based genotyping clearly showed that embryos from nongreen seeds were homozygous for the respective T-DNA insertion, indicating that the loss of function of PSP or PGDH1 led to embryo lethality (Figure 5D; see Supplemental Figure 5C online).

Figure 5.

Phenotype of pgdh1–1/+ and pgdh1–2/+ Heterozygous Knockout Mutants.

(A) Two allelic T-DNA insertion lines for PGDH1 were analyzed by PCR using gene-specific (pgdh1–1 [414 and 452] and pgdh1–2 [474 and 475]) and T-DNA–specific primers (pgdh1–1 [473] and pgdh1–2 [539]). The T-DNA insertion was either localized in the second intron (pgdh1–1) or in the last exon (pgdh1–2) of the PGDH1 gene.

(B) Seeds in mature siliques of heterozygous pgdh1–1/+ and pgdh1–2/+ lines were analyzed. Asterisks indicate nongreen, translucent seeds within siliques of segregating heterozygous lines.

(C) Bright (nongreen) and green seeds collected from siliques of heterozygous lines were cleared and analyzed by differential interference contrast microscopy. Arrows mark the position of the embryo within the seed.

(D) Embryos of bright (b) or green (g) seeds from heterozygous lines were extracted for isolation of genomic DNA. Zygosity of embryos was determined by PCR using gene-specific (pgdh1-1 [473 and 452] and pgdh1-2 [539 and 475]) and T-DNA–specific (pgdh1-1, 414 and 452; pgdh1-2, 474 and 475) primers. PCR products were separated on a 1% agarose gel and visualized using ethidium bromide stain. The 1 Kb DNA Ladder (Invitrogen) was used for sizing DNA fragments from 250 to 12,000 bp.

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

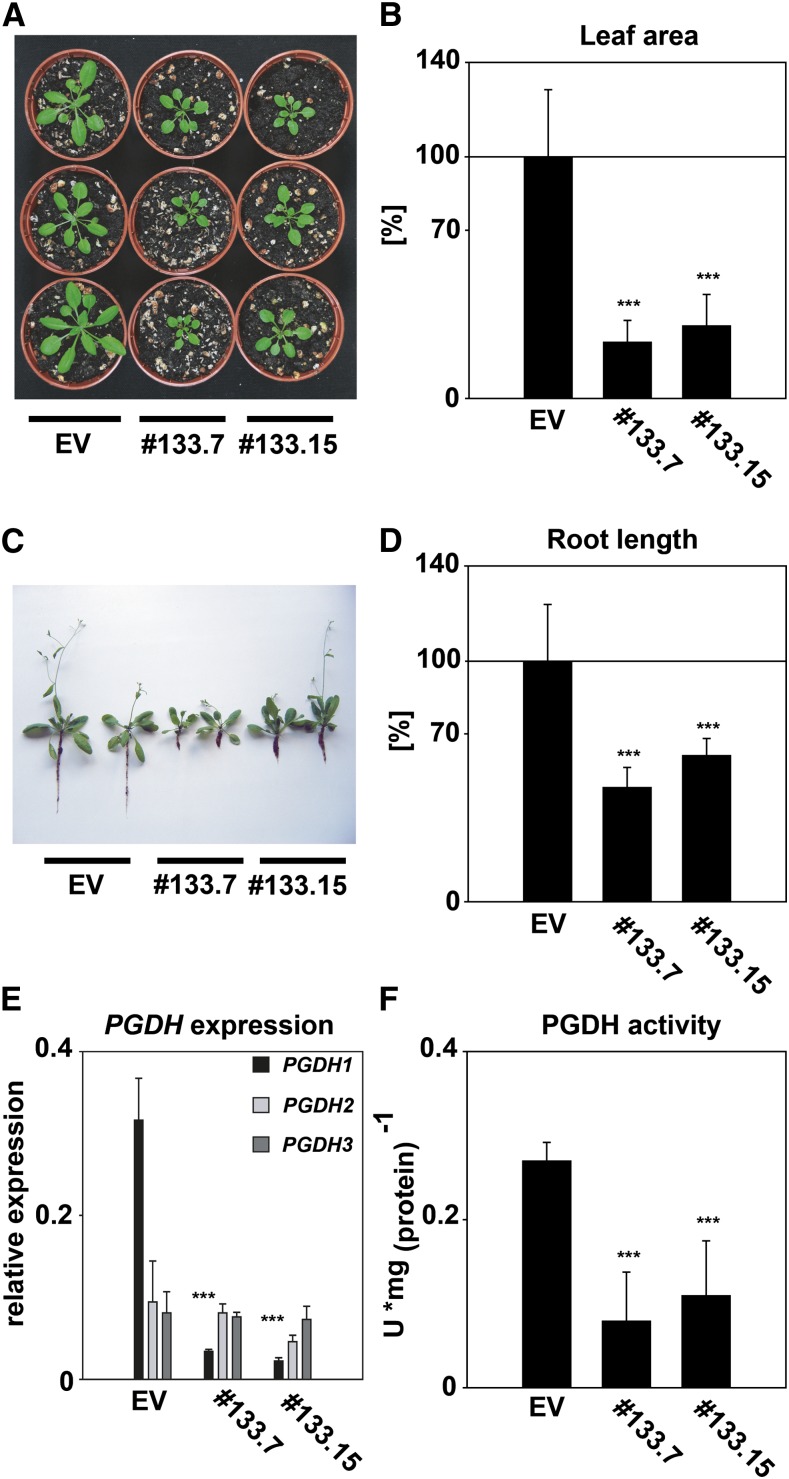

Because we could not obtain homozygous loss-of-function mutants for PGDH1, we generated PGDH1-silenced plants using a microRNA-based approach (Felippes et al., 2012). Transgenic plants harboring the empty vector construct were generated as a control and are further referred to as EV.

Silencing of PGDH1 led to a strong growth inhibition of transgenic plants (Figure 6A), with a significantly reduced leaf area and root length (Figures 6B and 6D). Among several lines exhibiting the same phenotype, two lines (133.7 and 133.15) were selected for further investigation. In both lines, the overexpression of the artificial silencing construct led to a significant repression of the PGDH1 transcript, whereas the expression of PGDH2 and PGDH3 was unaltered (Figure 6E). Moreover, both silencing lines showed a significant reduction in total PGDH activity to ∼40% that of the control (Figure 6F), indicating that PGDH1 is a major contributor to total PGDH activity in Arabidopsis.

Figure 6.

Phenotype of PGDH1-Silenced Plants.

(A) Shoot phenotype of PGDH1-silenced plants (lines 133.7 and 133.15) grown under standard greenhouse conditions.

(B) Leaf area for EV control and PGDH1-silenced plants is shown as a percentage of the control. The data represent the mean of 10 to 15 plants.

(C) Root phenotype of mature PGDH1-silenced and control plants grown on soil. Root-adhering soil particles led to the dark appearance of the roots.

(D) Root length of EV and PGDH1-silenced plants grown on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium without Suc. The data represent the mean of 12 to 14 plants.

(E) Relative expression of PGDH1, PGDH2, and PGDH3 genes in the EV control and PGDH1-silenced plants. The values represent the mean of four independent measurements.

(F) Specific PGDH activity in EV control and PGDH1-silenced plants. The values represent the mean of four independent measurements.

Error bars indicate the sd. ***P ≤ 0.01.

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

In addition to the growth-inhibition phenotype of adult plants, lines 133.7 and 133.15 also showed a delay of the heterotrophic phase of seedling development (see Supplemental Figure 6A online). The growth phenotypes at both developmental stages were reverted to the wild type by growing plants on medium supplemented with Ser (see Supplemental Figure 6A and 6B online). A clear growth-promoting effect of Ser on the silenced lines was observed, whereas growth of the EV control appeared to be slightly inhibited on medium supplemented with 100 µM Ser (see Supplemental Figure 6A and 6B online). Notably, the reduced root-growth phenotype of lines 133.7 and 133.15 disappeared at the much lower concentration of 10 µM Ser in the medium, a concentration that did not negatively affect growth of the EV control (see Supplemental Figure 6B online).

PS Biosynthesis Is Particularly Important in High CO2 Conditions

Because the PS pathway might be of particular importance for Ser biosynthesis in conditions of decreased or absent photorespiration, we compared the growth of PGDH1-silenced plants in ambient and elevated CO2 conditions.

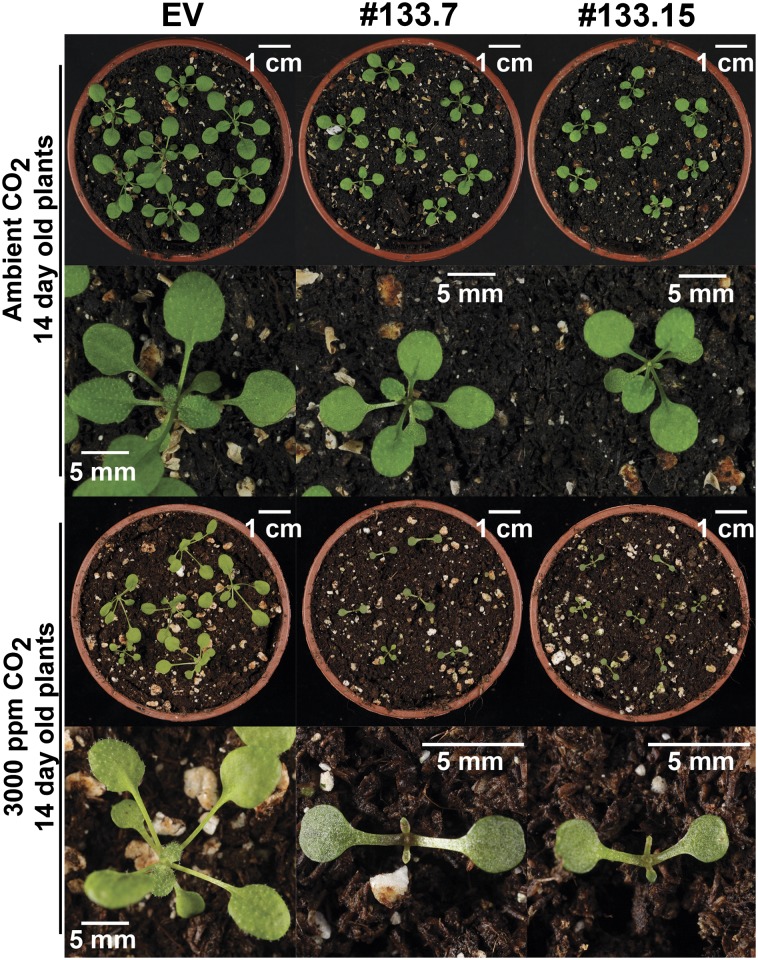

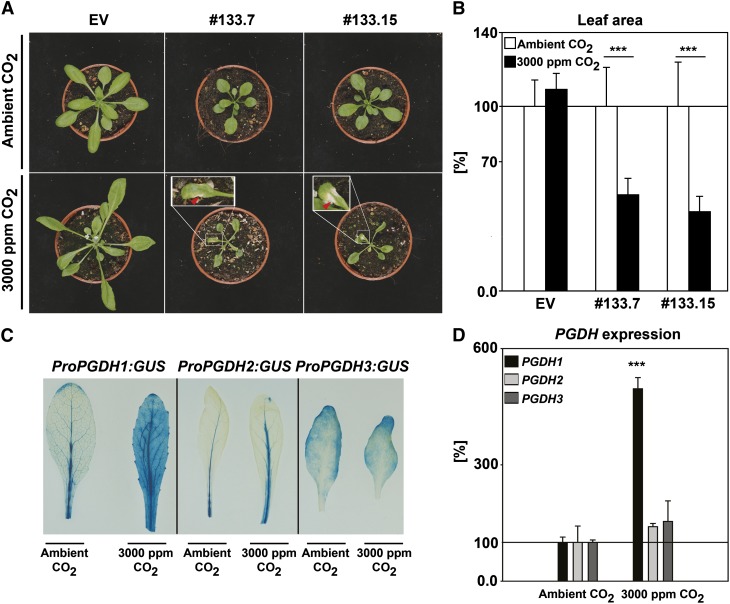

In elevated CO2 conditions, the development of rosette leaves was completely abolished in the silenced lines, whereas the development of the EV control plants was not affected (Figure 7). To study the influence of a high CO2 concentration on the metabolism of mature leaves, EV control and PGDH1-silenced plants were germinated and initially grown at ambient CO2 and were subsequently transferred to high CO2 conditions for 5 d. This short-term high CO2 exposure led to a strong inhibition of leaf growth and to the occurrence of lesions in young and mature leaves of the PGDH1-silenced plants (Figures 8A and 8B). By contrast, growth of the EV control plants was not affected by high CO2 concentrations (Figures 8A and 8B). Transcript analysis by quantitative RT-PCR and histochemical staining of plants expressing the GUS gene under control of the PGDH1 promoter clearly showed a significant induction of PGDH1 expression when plants were grown at high CO2 levels, whereas expression of PGDH2 and PGDH3 did not change (Figures 8C and 8D).

Figure 7.

Germination of PGDH1-Silenced Plants in High CO2 Conditions.

Developmental phenotype of PGDH1-silenced plants (lines 133.7 and 133.15) and EV control germinated and grown for 14 d at ambient CO2 or at high CO2 (3000 ppm).

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

Figure 8.

Phenotype of Mature PGDH1-Silenced Plants after 5 d in Elevated CO2 Conditions.

(A) Visible lesion phenotype (red arrows) of 21-d-old PGDH1-silenced plants (lines 133.7 and 133.15) grown for 5 d at elevated CO2.

(B) Leaf area of plants grown for 5 d at high CO2 (black bars) compared with plants grown at ambient CO2 (white bars, control). Values are given as a percentage of the EV control and represent the mean of five to seven replicates.

(C) Histochemical staining of GUS activity in plants expressing ProPGDH1:GUS, ProPGDH2:GUS, and ProPGDH3:GUS constructs grown at ambient and high CO2.

(D) Relative expression of PGDH1, PGDH2, and PGDH3 in plants grown at ambient and high CO2 levels. Values represent the mean of three independent measurements.

Error bars indicate the sd . ***P ≤ 0.01, significant differences between control and PGDH1-silenced plants.

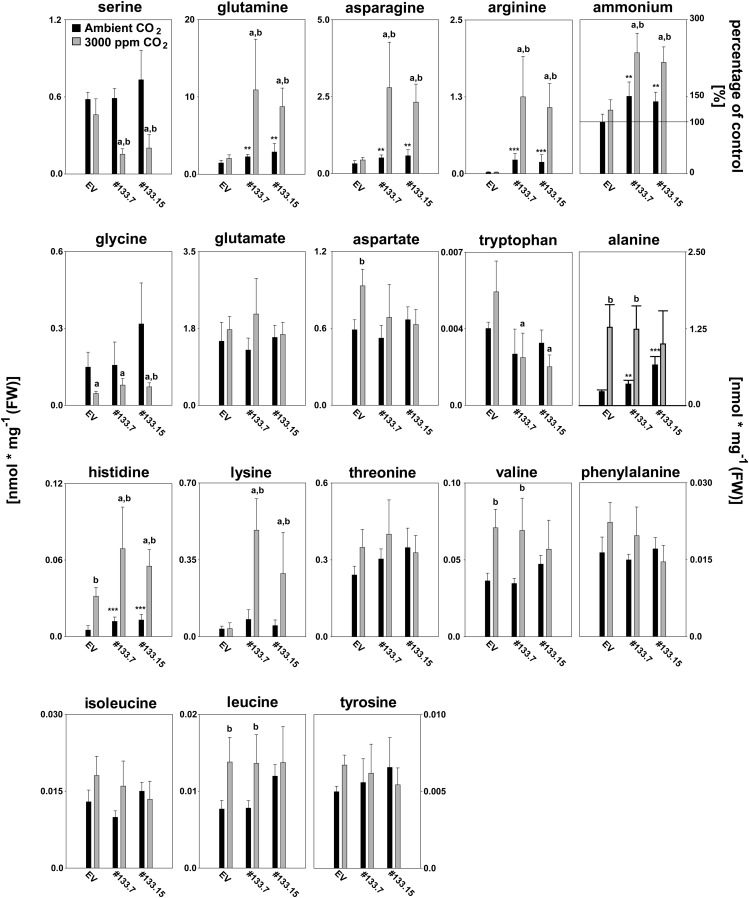

Because alteration of Ser biosynthesis might also lead to a general perturbation of amino acid metabolism, we analyzed the amino acid and ammonium concentration of silenced lines under ambient and elevated CO2 conditions. At ambient CO2 levels, Gln, Asn, Arg, Ala, His, and ammonium accumulated in leaves of PGDH1-silenced plants, whereas the concentration of none of the other amino acids was significantly altered in comparison to the EV control (Figure 9). The transfer of PGDH1-silenced lines to high CO2 conditions led to a strong increase in Gln, Asn, Arg, His, Lys, and ammonium levels. By contrast, the Ser concentration was significantly reduced in silenced plants upon transfer to elevated CO2 by >50% compared with the EV control and the nontreated plants (Figure 9). Under the same conditions, the concentration of most amino acids in the EV control remained unchanged. The only significant alterations observed were a 50% reduction in Gly and a minor increase in aspartate, Ala, His, and Leu concentrations compared with plants grown at ambient CO2 levels (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Metabolic Alterations in PGDH1-Silenced Plants in Ambient and High CO2 Conditions.

Alteration in amino acid and ammonium concentration in PGDH1-silenced plants (lines 133.7 and 133.15) and EV control plants. Plants were grown for 21 d at ambient CO2 before transfer for 5 d to high CO2 conditions (gray bars). In parallel, plants grown at ambient CO2 were used as a control (black bars). Bars represent the mean of six to eight replicates, and error bars indicate the sd. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.05; ***P ≤ 0.01, significant differences between control and PGDH1-silenced plants at ambient CO2 . aSignificant differences at between control and PGDH1-silenced plants at high CO2 levels (P ≤ 0.05). bSignificant differences between high CO2- and ambient CO2-grown plants (P ≤ 0.05).

The PS Pathway Delivers Ser for the Synthesis of Trp and Its Derivatives

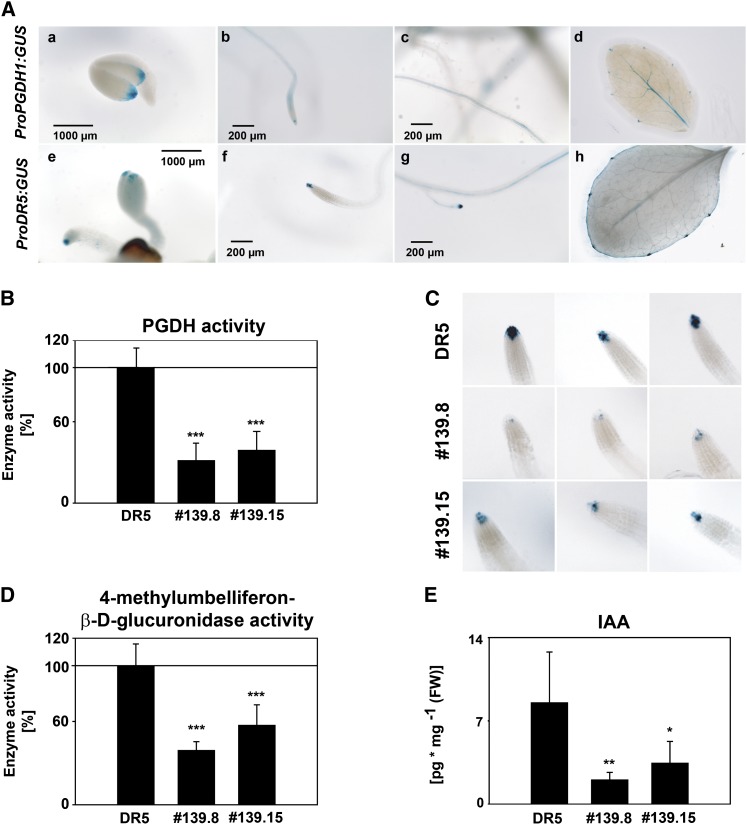

The in silico analysis of publicly available expression data (CSB.DB, http://csbdb.mpimp-golm.mpg.de; ATTED, http://atted.jp) revealed a strong coexpression of PGDH1 and PSAT1 with genes involved in Trp biosynthesis (see Supplemental Table 1 online). Analysis of the tissue-specific expression of PGDH genes revealed a distinct expression pattern of PGDH1, which overlapped with the activity of DR5, a synthetic auxin response element (Figure 10A). PGDH1- and DR5-driven GUS expression were observed at the tips of the cotyledons, within the root vasculature, at the tip of the root, and in the leaf margin (Figures 10A to 10D). To test the influence of reduced PGDH1 activity on the auxin response, the PGDH1 silencing construct was transformed into the background of the ProDR5:GUS line. The selected plant lines (139.8 and 139.15) exhibited a total PGDH activity that was 70% less than in the control (nontransformed ProDR5:GUS line) and showed the same growth phenotype as described for lines 133.7 and 133.15 (see Supplemental Figure 6C online). Differences in auxin response were visualized by staining the seedlings with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronic acid (X-Gluc) and were quantified by measuring the conversion of 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-d-glucuronide (MUG) in a fluorometric assay (Lewis et al., 2007). In 4-d-old seedlings, PGDH1 expression was high within the root and at the tips of the cotyledons (see Supplemental Figures 7A to 7E online). All lines with reduced PGDH1 activity showed less GUS staining at the root tip and the GUS activity was >50% lower than in the control (Figures 10B to 10D), suggesting a decreased auxin accumulation in these lines. To validate these results, the auxin concentration was additionally quantified in 4-d-old seedlings by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). In both silenced lines, the auxin concentration was significantly reduced to <50% of the concentration of control plants (Figure 10E).

Figure 10.

Association of the PS Pathway with Local Auxin Biosynthesis.

(A) Overlapping localization of GUS activity between plants expressing the uidA gene either under the control of the PGDH1 promoter ([a] to [d]) or under control of the auxin-responsive DR5 promoter ([f] to [i]). GUS activity was determined in seedlings ([a] and [e]), root tips ([b] and [f]), root vasculature ([c] and [g]), and the margin/serration of developing leaves ([d] to [h]).

(B) PGDH activity was determined in control (DR5) and PGDH1-silenced lines (139.8 and 139.15). PGDH activity is given as a percentage of the DR5 control. Bars represent the mean of four independent replicates.

(C) GUS staining in root tips of DR5 control and PGDH1-silenced plants. GUS activity was determined by staining 4 d after imbibition.

(D) Auxin accumulation was determined in seedlings of the DR5 control and PGDH1-silenced plants at 4 d after imbibition. GUS activity was quantified by the 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-d-glucuronide fluorometric assay (Lewis et al., 2007). GUS activity is shown as a percentage of the DR5 control. Bars represent the means of four to six independent replicates.

(E) Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) concentration was measured by ELISA in 4-d-old seedlings of DR5 control and PGDH1-silenced plants. Bars represent the means of six independent replicates.

Error bars indicate the sd. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.05; ***P ≤ 0.01.

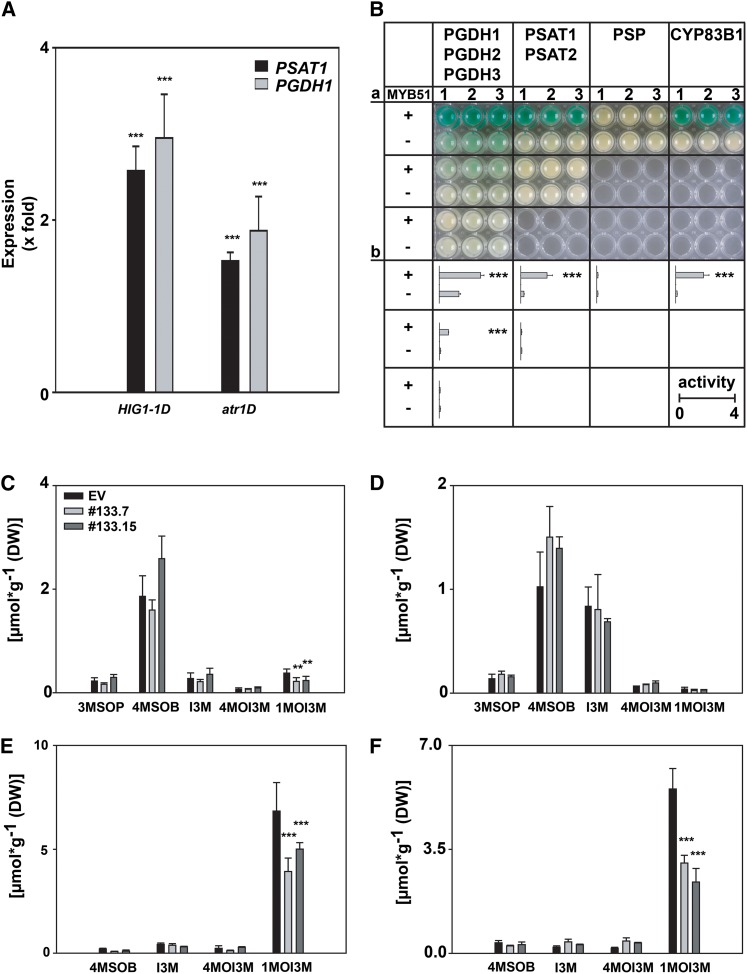

To examine the link between the PS pathway and Trp biosynthesis, the expression of PGDH1 and PSAT1 was analyzed in plants that overexpressed High Indolic Glucosinolate1 (HIG1/MYB51) or Altered Tryptophan Regulation1 (ATR1/MYB34), known transcriptional regulators of Trp biosynthesis (Celenza et al., 2005; Gachon et al., 2005; Gigolashvili et al., 2007). In both overexpressing lines, expression of PGDH1 and PSAT1 was enhanced (Figure 11A; Malitsky et al., 2008). In addition, we performed a trans-activation assay using cultured Arabidopsis root cells (Berger et al., 2007) to test whether the MYB51 transcription factor activates any PS pathway gene promoters. Staining and fluorometric determination of GUS activity revealed a significant activation of PGDH1, PGDH2, and PSAT1 promoters, whereas the activity of the PGDH3, PSAT2, and PSP promoters remained unaffected by MYB51 (Figure 11B). Apart from regulating Trp biosynthesis genes, MYB51 is a central regulator of genes of the Trp-derived indolic glucosinolate pathway (Gigolashvili et al., 2007).

Figure 11.

Association of the PS Pathway with Indolic Glucosinolate Biosynthesis.

(A) Expression of PGDH1 and PSAT1 in HIG1-1D and atr1D transformants Celenza et al., 2005). Bars represent the means of four independent replicates.

(B) Trans-activation assay of PS pathway promoter:uidA fusions and the ProCYP83B1:GUS positive control is shown. Fusion constructs of the respective promoters were coexpressed with Pro35S:MYB51 in cultured Arabidopsis root cells and GUS activity was determined by staining (a) or by measuring the 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-d-glucuronidase activity in nmol (4-MU) ⋅ min−1 ⋅ mg−1 protein (b). The data shown in (a) consist of three independent replicates and were repeated twice. The bars in (b) represent the means of six independent replicates and were repeated twice. Asterisks indicate significant difference in 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-D-glucuronidase activity between samples expressing PS pathway promoter:uidA fusions constructs alone or in combination with Pro35S:MYB51 constructs.

(C) Glucosinolate concentration in leaves of PGDH1-silenced plants (lines 133.7 and 133.15) and EV control plants grown on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium without Suc. The mean of eight replicates is shown.

(D) Glucosinolate concentration in leaves of PGDH1-silenced plants and EV control plants grown on soil in standard greenhouse conditions. The mean of eight replicates is shown.

(E) Glucosinolate concentration in roots of PGDH1-silenced plants and EV control plants on half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium without Suc. The mean of eight replicates is shown.

(F) Glucosinolate concentration in roots of PGDH1-silenced plants and EV control plants grown on soil in standard greenhouse conditions. The mean of eight replicates is shown.

3MSOP, 3-methylsulphinylpropyl-glucosinolate; 4MOI3M, 4-methoxyindol-3-ylmethyl glucosinolate; 4MSOB, 4-methylsulphinylbutyl glucosinolate; DW, dry weight; I3M, indol-3-ylmethyl glucosinolate.

Error bars indicate the sd. **P ≤ 0.05; ***P ≤ 0.01.

To assess a possible link between the PS pathway and the indolic glucosinolate biosynthetic pathway, plants of the PGDH1-silenced lines were harvested and the concentration of glucosinolates was analyzed (Figures 11C to 11F). In leaves of silenced plants, no significant changes in aliphatic glucosinolate concentration were observed and only the concentration of the 1-methoxyindole-3-ylmethyl glucosinolate (1MOI3M) was reduced (Figures 11C and 11D). By contrast, the concentration of 1MOI3M was significantly reduced in roots of the PGDH1-silenced plants (Figures 11E and 11F).

Camalexin represents another important secondary metabolite derived from Trp and its biosynthesis is induced upon infection with necrotrophic pathogens such as Botrytis cinerea (Windram et al., 2012). To test the influence of B. cinerea infection on the PS pathway, leaves of promoter GUS lines containing the respective promoters of PS pathway genes were infected with B. cinerea as described by Windram et al. (2012) and GUS activity was analyzed 4 d after infection. The promoter activity of PGDH1, PSAT1, and PGDH2 was enhanced at the site of infection, indicating an activation of the respective promoters (see Supplemental Figure 8B online). By contrast, the PSP, PGDH3, and PSAT2 promoters were not activated, as indicated by the lack of elevated GUS staining at the site of infection (see Supplemental Figure 8B online).

DISCUSSION

PS Biosynthesis Takes Place in Plastids and Is Essential for Plant Development

The first committed step of the PS pathway is catalyzed by the PGDH enzyme (Slaughter and Davies, 1968; Ho et al., 1999b; Ho and Saito, 2001).

The biochemical characterization of the putative PGDH enzymes revealed that all three isoenzymes catalyze the 3-PGA to 3-PHP conversion (Table 1) and substrate affinities and catalytic efficiencies are comparable to those for PGDH from Triticum aestivum (Rosenblum and Sallach, 1970).

In several organisms, PGDH enzymes are known to be feedback regulated by Ser (Pizer, 1963; Dey et al., 2005), whereas such a mechanism has been controversial in plants (Slaughter and Davies, 1968; Rosenblum and Sallach, 1970). In Arabidopsis, PGDH1 and PGDH3 were sensitive to Ser concentrations of 1 and 5 mM, whereas PGDH2 was completely insensitive (Figure 3). The Ser concentrations in the stroma of chloroplasts and heterotrophic plastids were estimated to range from 1.7 to 4.3 mM (Mills and Joy, 1980; Winter et al., 1994; Farré et al., 2001). On the basis of these concentrations, PGDH1 and PGDH3 would be partly inhibited in both types of plastids and hence substrate feedback inhibition might be one mechanism to regulate PGDHs in Arabidopsis.

Transiently expressed PGDH:GFP fusion proteins of the three Arabidopsis PGDH isoenzymes all localized to chloroplasts (Figure 2); however, PGDH1 and PGDH2 are dominantly expressed in heterotrophic tissue (Figure 4). These data indicate that the PS pathway might be more important for Ser biosynthesis in plastids of nonphotosynthetic tissue, which is further supported by the embryo-lethal phenotype of pgdh and psp mutants (Figure 5; see Supplemental Figure 5 online).

During embryo development, the cell division rate in meristems, in which PGDH1 and PSP are preferentially expressed (Figure 4; see Supplemental Figure 7 online), is high and thus so is the demand for Ser as a substrate for protein biosynthesis and as a precursor for other important metabolites. Embryo lethality has frequently been observed in mutants with functionally disrupted metabolic enzymes, although the exact cause of abortion often remains unknown (Cairns et al., 2006; Muralla et al., 2007; Meinke et al., 2008; Székely et al., 2008). Recently, it has been shown that the biosynthesis of phosphatidylserine, a phospholipid synthesized from Ser, is important for plant reproduction. Mutation of PHOSPHATIDYLSERINE SYNTHASE1 led to embryo lethality and affected microspore development (Yamaoka et al., 2011). The lack of Ser normally synthesized via the PS pathway might result in reduced phosphatidylserine synthesis and lead to the abortion of embryos homozygous for pgdh1 or psp mutations. However, it cannot be excluded that decreased Ser supply to other cellular processes also affects embryo vitality in pgdh1 and psp mutants.

Apart from its vital function during embryo development, the PS pathway appears to play an additional role in mature plants. Plants with reduced PGDH1 activity show reduced shoot and root growth (Figure 6), whereas disruption of the PGDH2 gene did not lead to any obvious morphological or metabolic phenotype (see Supplemental Figures 3 and 4 online). In comparison with PGDH1, PGDH2 is only weakly expressed, which together with the wild-type–like phenotypic growth of mutants, might indicate a rather minor role of this isoenzyme in plant metabolism.

According to our metabolite analyses, the Ser concentration of PGDH1-silenced plants was unaltered compared with the control (Figure 9; see Supplemental Figure 9 online), but silenced plants still displayed severely reduced growth (Figure 6) and increased levels of some other amino acids (Figure 9). The majority of the total Ser measured in whole leaf or root extracts of silenced plants is likely synthesized during photorespiration, because this pathway represents the major source of Ser in plants. By contrast, Ser generated via the PS pathway might be limited to a few cell types and account for only a small fraction of total Ser. Thus, decreased Ser synthesis via the PS pathway might not be detected on a whole organ basis. External supply of Ser to PGDH1-silenced plants rescued the root-growth phenotype (see Supplemental Figure 6A and 6B online). Therefore, the observed growth defects of PGDH1-silenced plants appear to originate from Ser deficiency in specific cells, which are insufficiently supplied with Ser synthesized by photorespiration.

When plants were grown at high CO2 levels to inhibit photorespiratory Ser biosynthesis, leaf initiation was completely abolished in seedlings of PGDH1-silenced plants (Figure 7). PGDH1 and other genes of the PS pathway are predominantly expressed in cells of the SAM and RAM (Figure 4; see Supplemental Figure 10 online). Because leaf initiation is a function of the SAM (Micol and Hake, 2003; Murray et al., 2012), our findings indicate that the synthesis of Ser in the SAM via the PS pathway is important for leaf initiation and growth.

In proliferating cells of the meristem, Ser might be important as a donor of C1 units for 5,10-methylene-tetrahydrofolate (5,10-CH2-THF) synthesis in plants (Douce et al., 2001; Jabrin et al., 2003; Sahr et al., 2005; Rébeillé et al., 2007). The transfer of C1 units mediated by THF is important for metabolic processes such as the synthesis of S-adenosylmethionine and nucleotides (Hesse et al., 2004; Ravanel et al., 2004; Zrenner et al., 2006). In proliferating cells, the rate of nucleic acid synthesis is high and consequently, so is the demand for nucleotides and S-adenosylmethionine for methylation reactions. Thus, a reduced Ser biosynthesis in the meristem would affect nucleic acid synthesis and subsequently cell proliferation.

However, in PGDH1-silenced plants grown at ambient CO2 levels, leaf development is not as strongly affected as under elevated CO2 (Figure 7), indicating that in early stages of leaf development, Ser can also be synthesized by photorespiration. Because cotyledons are autotrophic organs (Marek and Stewart, 1992), Ser will most likely be synthesized via photorespiration and transported to the SAM via the phloem. Taken together, Ser synthesized by either photorespiration or PS pathway is essential for proper leaf development in plants.

The PS Pathway Compensates the Lack of Photorespiratory Ser Biosynthesis

Although photorespiration is an important pathway in primary plant metabolism, plants are able to develop normally at nonphotorespiratory high CO2 conditions (Somerville and Ogren, 1980; Bauwe et al., 2010; Maurino and Peterhansel, 2010; Eisenhut et al., 2013). Therefore, an alternative source of Ser is required to compensate for the lack of photorespiratory Ser biosynthesis at high CO2 concentrations. The expression of PGDH1 is dramatically enhanced in the whole leaves of plants grown for 5 d at high CO2 levels and leaf growth of mature PGDH1-silenced plants is severely impaired (Figures 8C and 8D). In addition, the Ser concentration of these plants is significantly reduced (Figure 9). Therefore, our data indicate that under high CO2 conditions, the PS pathway assumes the role of providing Ser.

Furthermore, impairment in Ser biosynthesis via the PS pathway led to other notable but unexpected effects on plant amino acid metabolism; the concentrations of several amino acids were significantly increased in PGDH1-silenced plants upon transfer to high CO2 concentrations (Figure 9).

Recently, metabolomic studies of a variety of mutants uncovered a thus far unexpected complexity in amino acid metabolism in plants (Jander et al., 2004; Joshi et al., 2006; Lu et al., 2008; Araújo et al., 2010). For example, mutants defective in branched chain amino acid degradation accumulate a broad range of amino acids in seeds (Gu et al., 2010). Because the biosynthesis of amino acids accumulating in these mutants is obviously unrelated to the mutation, their accumulation seems to be a pleiotropic effect. Hence, increased amino acid concentrations in leaves of PGDH1-silenced lines may also reflect a pleiotropic effect. On the other hand, the accumulation of only nitrogen-rich amino acids in PGDH1-silenced lines might rather point to a specific effect as observed in the presence of excess ammonium due impaired ammonium assimilation (Coschigano et al., 1998; Lancien et al., 2000, 2002; Potel et al., 2009). Ammonium does, in fact, accumulate in PGDH1-silenced plants in both photorespiratory and nonphotorespiratory conditions (Figure 9). Thus, the necrotic lesions that appeared on leaves of these plants at high CO2 concentrations might be the result of toxic ammonium accumulation (Figure 8) (Platt and Anthon, 1981; Britto and Kronzucker, 2002). The PSAT reaction represents a potential link between ammonium assimilation and the PS pathway, in which the amino group from Glu is transferred to 3-PHP, resulting in one molecule of 2-oxoglutarate and one molecule of PS (Figure 12D). The 2-oxoglutarate released by this reaction can be directly used for ammonium fixation via the glutamine synthetase/glutamine oxoglutarate aminotransferase (GS/GOGAT) cycle. In plants deficient in PS biosynthesis, this recycling mechanism is disturbed, because less 2-oxoglutarate is released from the PSAT reaction. This effect becomes important at high CO2 levels when flux through the PS pathway is enhanced, whereas photorespiratory 2-oxoglutarate synthesis is diminished. Because the additional lack of 2-oxoglutarate synthesis in PGDH1-silenced lines would affect ammonium assimilation by the GS/GOGAT cycle, the plant might use different pathways for ammonium fixation to detoxify ammonium and maintain the amino acid pool in leaves. Beside the GS/GOGAT cycle, plants possess three additional pathways for ammonium assimilation (Potel et al., 2009). First, ammonium can be integrated into Asn by Asn synthetase. Second, carbamoylphosphate, an essential precursor for Arg and pyrimidine biosynthesis, is formed by carbamoylphosphate synthetase using bicarbonate, ATP, and ammonium. Finally, in the presence of high ammonium levels, plants incorporate ammonium into Glu by NADH-Glu dehydrogenase (Skopelitis et al., 2006). Increased flux through all three pathways would explain why nitrogen-rich amino acids are accumulating in PGDH1-silenced lines at a high CO2 level.

Figure 12.

Model for the Functions of the PS Pathway in Plants.

The PS pathway is essential for the synthesis of Ser and its derivatives in specific cells of developing embryos (A), the SAM (B), and the root (C). Furthermore, at high CO2 levels, the PS pathway compensates for Ser biosynthesis via photorespiration and provides 2-oxoglutarate for Glu synthesis and subsequently ammonium fixation by the GS/GOGAT cycle (D).

Ineffective PS Biosynthesis Impairs the Synthesis of Trp-Dependent Secondary Metabolites

Ser is an important precursor for the biosynthesis of several essential compounds in plants. The coexpression data indicated a possible function of the PS pathway in Trp biosynthesis, because PGDH1 and PSAT1 are strongly coexpressed with genes of Trp metabolism (see Supplemental Table 1 online). The correlation between both pathways is reasonable, because Trp is synthesized by the condensation of Ser and indole (Radwanski and Last, 1995; Miles, 2001; Tzin and Galili, 2010; Dunn, 2012).

Involvement of the PS pathway in Trp biosynthesis is further supported by the tissue-specific expression pattern of PS pathway genes. Several Trp biosynthesis genes are highly expressed within cells of the vasculature and meristem (Pruitt and Last, 1993; Birnbaum et al., 2003; Sazuka et al., 2009) and therefore strongly overlap with the expression of PS pathway genes. However, conclusions based solely on promoter GUS studies have to be drawn with caution because the intensity of GUS signal can differ significantly depending on the promoter sequence used (Rose and Last, 1997).

Additional evidence for an association of the PS pathway and Trp metabolism came from reduced auxin and 1MOI3M concentrations in PGDH1-silenced lines (Figures 10 and 11). 1MOI3M represents the major indolic glucosinolate present in roots and both auxin and indolic glucosinolates are synthesized from a common Trp-derived precursor indole-3-acetaldoxime. Therefore, the metabolic phenotype of the PGDH1-silenced lines resembles the phenotype observed for mutants defective in the biosynthesis of indole-3-acetaldoxime (Zhao et al., 2002). The interaction between both pathways, however, seems to be restricted to certain cells, because the Trp concentration, similar to the whole tissue concentration of Ser, was not significantly altered in PGDH1-silenced plants (Figure 9; see Supplemental Figure 9 online).

Although local auxin biosynthesis is known to be essential for proper meristem function (Vernoux et al., 2010), auxin deficiency owing to reduced Trp biosynthesis in meristems does not appear to be the only reason for the short-root phenotype of PGDH1-silenced plants because it could not be reverted by supplementing the growth medium with Trp (see Supplemental Figure 6B online).

In addition, expression analyses of PS pathway genes further support an interaction between the Trp and PS biosynthesis. The expression of genes involved in Trp and indolic glucosinolate biosynthesis is regulated by two transcription factors, HIG1/MYB51 (Gachon et al., 2005; Gigolashvili et al., 2007) and ATR1/MYB34 (Celenza et al., 2005). We found that the genes of the PS pathway are regulated by the same transcription factors (Figure 11). These results are consistent with recent data from Malitsky et al. (2008), which showed that the activities of HIG1/MYB51 and ATR1/MYB34 are not restricted to core Trp and indolic glucosinolate biosynthesis, but are also involved in the regulation of pathways at the interface between primary and secondary metabolism. However, the regulation of PS pathway gene expression appears to be more complex, because the activities of the PGDH1, PGDH2, and PSAT1 promoters were also induced in plants subjected to infection with B. cinerea (see Supplemental Figure 8 online). Plants attacked by necrotrophic pathogens such as B. cinerea typically reduce the synthesis of glucosinolates, whereas substantial amounts of the Trp-derived phytoalexin camalexin are produced (Denby et al., 2004; Kliebenstein et al., 2005; Rauhut and Glawischnig, 2009). Camalexin is synthesized immediately at infection sites; thus, upregulation of the PS pathway might be important to ensure Trp and subsequently camalexin biosynthesis in plants, under conditions or in tissues in which Ser cannot be delivered by photorespiration.

In summary, we provide evidence for an essential function of the PS pathway in nonphotosynthetic tissues such as developing embryos and the SAM and RAM. Here our data revealed an unexpected role of Ser as an essential metabolite for meristematic cell proliferation because absence of the PS pathway caused defects in embryo development and led to reduced leaf and root growth in mature plants.

The effect of PS pathway loss in PGDH1-silenced plants could be partially compensated by photorespiratory Ser biosynthesis, and upregulation of the PS pathway in plants grown under nonphotorespiratory conditions indicated that both pathways work in concert and are able to partly compensate for one another. Furthermore, our results indicate involvement of the PS pathway in the biosynthesis of Trp-derived defense-related metabolites and in auxin biosynthesis.

Future research will enable a more detailed understanding of the interaction of photorespiratory and PS pathway–mediated Ser biosynthesis and its implication for plant development and metabolism.

METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

All plants used in this study are of the Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Col-0. Plants germinated on soil (Einheitserde Classic; Einheitserde- und Humuswerke Sinntal-Altengronau) or on plates were stratified for 2 d in the dark at 4°C. For sterile culture, plants were cultivated on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium including modified vitamins (M0245.0050; Duchefa) without Suc. Plants were grown under standard greenhouse conditions (16-h light/8-h dark; 140 to 200 µmol m−2/s−1 photon flux density and a temperature of 21°C at 50% relative humidity). High CO2 experiments were conducted either with 21-d-old plants that were grown at ambient CO2 conditions (∼300 ppm) before transfer for 5 d to high CO2 conditions (3000 ppm) or with plants grown from seeds that were directly germinated in high CO2 conditions. Botrytis cinerea infection of Arabidopsis leaves was conducted according to Windram et al. (2012). Five microliters of spores (1 × 105 spores × mL−1) were pipetted onto detached leaves of 25-d-old plants. Leaves were placed on wet filter paper in a Petri dish and incubated for 2 d.

Isolation of T-DNA Insertion Mutants and Generation of PGDH1-Silenced Plants

Putative T-DNA insertion lines for the PGDH1, PGDH2, and PSP genes of Arabidopsis (Col-0) (SAIL_209_G08 [pgdh1–1/+], GK-155B09 [pgdh1–2/+], SALK_069543 [pgdh2–1], SALK_149747 [pgdh2–2], SALK_062391 [psp–1/+], and SAIL_658_A06 [psp–2/+]) were obtained from the European Arabidopsis Stock Centre. All T-DNA mutants were identified using the respective primers LBb1 and LBa1, together with an appropriate gene-specific primer (see Supplemental Table 2 online). For target-specific gene silencing, plants expressing the full-length PGDH1 sequence fused 3′ to the trans-acting small interfering RNA target miR173 were generated (Felippes et al., 2012). These lines are referred to as PGDH1-silenced lines. For this, full-length PGDH1 cDNA was amplified using a modified 5′-oligonucleotide that included the miR173 target sequence. The PCR amplicon was cloned into the pENTR/D-TOPO (Invitrogen) vector and recombined into the pAM-PAT-GWPro35S vector (Jakoby et al., 2006). The generated construct was transformed into the Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 pmp90RK and subsequently into Arabidopsis Col-0. Transformed plants were germinated on soil and transgenic lines were selected by spraying with glufosinate (BASTA).

Expression Analysis by Quantitative RT-PCR

To analyze PGDH1, PGDH2, and PGDH3 transcript levels in control plants and PGDH1-silenced lines, total RNA was extracted from 50 mg of plant material by hot phenol extraction, followed by a LiCl precipitation. Isolated RNA was digested with the TURBO DNA-free kit (Ambion) and 5 µg digested RNA was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis using Bioscript Reverse Transcriptase (Bioline), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To quantify the expression of the respective genes, quantitative PCR was performed using the 7300 Real-Time PCR System and SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Expression was analyzed from five biological replicates. Sequences of the primers used for the PCR reactions are listed in Supplemental Table 2 online.

Preparation of Seeds and Embryos for Microscopy and Genotyping

Siliques of Arabidopsis wild-type and mutant plants were harvested 12 to 14 d after flowering and fixed onto a glass slide using double-sided adhesive tape. Siliques were opened using forceps and seeds were isolated in water for embryo isolation or mounted in clearing solution (30 g gum arabic, 200 g chloral hydrate, 20 g glycerol, 50 mL water) for microscopy. To affect sufficient clearing of the seed coat and the embryo, seeds were incubated in clearing solution at least overnight. For microscopy, the cleared seeds were transferred to a glass slide and images were captured by differential interference contrast microscopy (Nikon Eclipse E800). Mature or immature embryos were obtained by removing the seed coat. The isolated embryos were rinsed at least four times with distilled water to prevent genomic DNA contamination from the seed coat and the endosperm. For genotyping, isolated embryos were collected in 100 μL DNA extraction buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 25 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS) and homogenized using a pestle; 35 μL 3M potassium acetate, pH 6.0, was added and the sample was centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000g. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and genomic DNA was precipitated by addition of 125 μL isopropanol followed by 10-min centrifugation at 12,000g. The remaining pellet was washed once with 75% ethanol and subsequently dissolved in 10 μL Tris-EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA). The zygosity of the respective T-DNA insertion of the different embryo types (mature green, immature bright) was determined by PCR.

Subcellular Localization of PGDH Isoenzymes

To determine the subcellular localization of PGDH1, PGDH2, and PGDH3, GFP fusion constructs were generated. Full-length cDNA and the 5′ region of PGDH1, PGDH2, and the PGDH3 were amplified by PCR and cloned into the pENTR/D-TOPO vector. Oligonucleotide sequences are provided in Supplemental Table 2 online. The generated ENTRY clones were recombined with the pGWB5 vector (Invitrogen) and the final constructs were transformed into the supervirulent A. tumefaciens strain LBA4404.pBBR1MCS.virGN54D (Koroleva et al., 2005). The obtained A. tumefaciens clones were subsequently used for transient expression of the fusion proteins in Nicotiana benthamiana. In addition to chlorophyll fluorescence, the triosephosphate phosphate translocator fused to GFP was used as positive control for chloroplastic localization (Flügge and Heldt, 1976). GFP fluorescence and chlorophyll autofluoresence were monitored using a Zeiss LSM 700 confocal laser-scanning microscope. GFP and chlorophyll were excited at 488 nm and emission was analyzed between 502 and 525 nm for GFP and between 600 nm and 650 nm for chlorophyll. Images were captured using ZEN 2009 software and were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS3.

Generation of Promoter:uidA Fusion Constructs for Transformation of Plants and Cultured Cells

To study the expression pattern of genes encoding the enzymes of the PS pathway, promoter GUS fusion constructs were generated. For all constructs, 1800 to 2000 bp upstream sequence from the start codon (ATG) was amplified from genomic DNA and cloned into the pENTR/D-TOPO vector (for oligonucleotide sequences, see Supplemental Table 2 online). The generated ENTRY clones were recombined with the pGWB3 destination vector (Invitrogen) containing the β-glucuronidase (uidA) gene. The final constructs were transformed into both the supervirulent A. tumefaciens strain LBA4404.pBBR1MCS.virGN54D (Koroleva et al., 2005) for transient expression in cultured Arabidopsis root cells and also into the A. tumefaciens strain GV3103 for stable transformation of Arabidopsis plants. Transgenic plants were selected on 1/2 Murashige and Skoog medium containing the respective antibiotics. Promoter activity was analyzed by detection of GUS activity after incubating the whole plant or plant parts in an assay solution containing X-Gluc as a substrate as previously described (Gigolashvili et al., 2007). Histochemical staining was monitored using a Leica S8AP0 binocular microscope and the respective LAS-EZ (2.1.0) software package.

Trans-Activation Assays Using the Promoter:uidA Fusion Constructs of PS Pathway Genes and the MYB51 Transcription Factor

The supervirulent Agrobacterium strain LBA4404.pBBR1MCS.virGN54D harboring the constructs for expressing the MYB51 transcription factor (Gigolashvili et al., 2007), the antisilencing protein p19, and the uidA gene under the control of the respective promoters were used for the transformation of cultured Arabidopsis root cells. The root cells were grown and transformed as previously described (Berger et al. (2007). GUS activity was visualized 5 to 6 d after transfection by adding 100 μL of staining solution (1 mM X-Gluc, 50 mM NaH2PO4, pH 7.1) to 3 mL of the cells followed by incubation for up to 12 h at 37°C. GUS staining was monitored using a Canon EOS 1100D digital camera. To quantitatively measure GUS activity, the pellet of 1.5 mL of the cell culture was homogenized in 500 μL extraction buffer (1 mM EDTA, 0.1% v/v Triton X-100, 50 mM NaH2PO4, pH 7.1) and centrifuged for 20 min at 4°C at 12,000g. Twenty-five microliters of supernatant was mixed with 200 μL MUG solution (22 mg 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-d-glucuronide in 50 mL extraction buffer) and incubated at 37°C. The increase in fluorescence intensity (excitation at 365 nm; emission at 455 nm) was measured every 90 s using a plate reader. The linear slope of the curve was determined and the values were normalized to the protein content within the extract. The total amount of protein in the extract was quantified according to the Bradford (1976) method.

Extraction and Measurement of Metabolites

Amino acids were extracted according to the methods of Giavalisco et al. (2009) and quantified following a modified protocol from Lindroth and Mopper (1979). Fifty milligrams (fresh weight) of freshly ground frozen plant tissue was extracted for 10 min at 25°C with 1 mL precooled (−15°C) extraction mixture (25% methanol, 75% methyl tert-butyl ether) followed by an incubation for 10 min in an ultrasonic bath. To separate the solid from the soluble and the polar from the lipophilic phases, 650 μL of a mixture of water:methanol (3:1) was added to the sample, which was then mixed and centrifuged for 5 min at maximum speed in a table-top centrifuge. After phase separation, 200 μL of the lower methanol:water phase was transferred to a HPLC vial and mixed with 800 μL HPLC-grade water. The extracts were subjected to HPLC analysis using a Hyperclone C18 ODS column (Phenomenex) connected to a HPLC system (Dionex). Amino acid concentrations were quantified by precolumn online derivatization with orthophthaldehyde in combination with fluorescence detection (Lindroth and Mopper, 1979). The ammonium concentration was determined using a protocol described by Bräutigam et al. (2007). For the analysis of glucosinolates, ∼100 mg (fresh weight) plant tissue was lyophilized overnight, homogenized with a tissue lyzer, and extracted with 1 mL 80% methanol (v/v) containing benzyl-glucosinolate as an internal standard. The final extract was loaded onto a self-made anion exchange column (DEAE Sephadex A25) and incubated overnight with sulfatase (E.C. 3.1.6.1; designated type H-1, from Helix pomatia; Sigma). Desulfoglucosinolates were eluted from the column with 3 × 2 mL HPLC-grade water and the eluate was dried overnight in a vacuum concentrator. The remaining pellet was resolved in 300 μL HPLC-grade water and the amount of desulfoglucosinolates was quantified by Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled to a Photo-Diode Array detector at 229 nm relative to the internal standard. Differences in auxin accumulation were determined indirectly, by analyzing the GUS activity in ProDR5:GUS and ProDR5:GUS/PGDH1-silenced lines. ProDR5:GUS signal was visualized by staining seedlings with X-Gluc for 12 h at 37°C, followed by 3 h destaining in 75% ethanol. Stained seedlings were placed on a glass slide and photographed using a Leica S8AP0 binocular microscope and the respective LAS-EZ (2.1.0) software package. To quantify alterations in auxin accumulation, total protein was extracted from seedlings (50 mg) of ProDR5:GUS and ProDR5:GUS/PGDH1-silenced lines and used for a MUG assay of GUS activity. Product formation was determined fluorometrically (365/455 nm) every 90 s as previously described by Lewis et al. (2007). The rate of product formation corresponds to the amount of GUS expression driven by the DR5 promoter and is therefore an indirect measure of auxin. Direct quantification of indole-3-acetic acid concentration in 4-d-old seedlings was performed ELISA according to the manufacturer's instructions (Uscn Life Science).

Cloning, Heterologous Expression, Purification, and Characterization of the PGDH Enzymes from Arabidopsis and E. coli

cDNA fragments encoding PGDH from Arabidopsis, lacking sequences encoding the predicted targeting signal, were amplified from cDNA by PCR using an appropriate proofreading Taq polymerase. The E. coli PGDH-encoding DNA fragment (SerA) was amplified from genomic DNA isolated from the E. coli strain DH5α. The PCR products were cloned into the pET16b expression vector (Novagen) by ligation. Restriction sites were incorporated within the DNA fragments using modified oligonucleotides for the PCR reaction (for primer sequences, see Supplemental Table 2 online). Cloning of DNA fragments into the pET16b vector allows in-frame insertions with a hexa-His-coding tag, resulting in a N-terminal His-tag fusion of the respective protein. Correctness of the clones was determined by sequencing and positive clones were transformed into the E. coli expression strain BLR21. Heterologous expression of the proteins was induced by application of 1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside during the exponential growth phase of the cell culture (OD600 of 0.5). Three hours after induction, cells were harvested by centrifugation (4000g, 20 min at 4°C) and the cell pellet was stored at −80°C until further use. The frozen cell pellet from a 500 mL cell culture was thawed on ice and resuspended in 7.5 mL lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0; 300 mM NaCL, 10 mM imidazole). For cell lysis, 1 mg/mL lysozyme, 10 ng/mL RNase A, and 1 U/mL DNase I were added and the suspension was incubated for 30 min at 4°C. Afterwards, the suspension was sonicated three times at 30% duty cycle and power level 3 using a Branson Sonifier equipped with a microtip. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (6000g 20 min at 4°C) and the clear cell lysate was transferred to a new tube. Two milliliters of prewashed Ni-NTA agarose was added to the cleared cell lysate, which was then incubated for 1 h at 4°C on a rotor. After incubation, the Ni-NTA matrix was pelleted by centrifugation (300g, 1 min) and resuspended in 4 mL wash buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0; 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole) and loaded onto a self-made cotton-plugged column. The matrix was washed again with 4 mL of wash buffer and the bound protein was subsequently eluted by adding 4 × 500 μL elution buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0; 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole). The elution fractions were desalted by size exclusion chromatography using NAP-5 columns (GE Healthcare). Before use, the columns were equilibrated using three column volumes of PGDH storage buffer (200 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT). Five hundred microliters of the elution fractions was loaded onto the equilibrated NAP-5 column and proteins were eluted with 1 mL PGDH storage buffer. The eluates were stored on ice until further use and the protein concentration was determined according to the Bradford (1976) method. The purity of the purified proteins was determined by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie staining and protein gel blot analysis using anti-His antibodies (see Supplemental Figure 1 online). PGDH activity was determined according to the Ho et al. (1999b) method with minor modifications. The assay was performed in a total volume of 200 μL containing 200 mM Tris, pH 8.1 or 7.2, 25 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM DTT, 5 mM hydrazine sulfate, 1 to 2 µg (PGDH of Arabidopsis), or ∼50 µg (SerA) of the purified enzyme and variable concentrations of the respective substrates and inhibitors.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the EMBL/GenBank data libraries under the following accession numbers: At4g34200 (PGDH1), At1g17745 (PGDH2), At3g19480 (PGDH3), At4g35630 (PSAT1), At2g17630 (PSAT2), and At1g18640 (PSP).

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure 1. Purification of the Heterologously Expressed PGDH1, PGDH2, and PGDH3 Enzymes by Ni-NTA Affinity Chromatography.

Supplemental Figure 2. Biochemical Characterization of PGDH Isoenzymes.

Supplemental Figure 3. Phenotype of pgdh2–1 and pgdh2–2 Homozygous Knockout Mutants.

Supplemental Figure 4. Biochemical Characterization of pgdh2–1 and pgdh2–2 Mutants.

Supplemental Figure 5. Embryo-Lethal Phenotype of psp–1 and psp–2 Mutants.

Supplemental Figure 6. Phenotype of PGDH1-Silenced (Lines 133.7 and 133.15) and EV Control Plants.

Supplemental Figure 7. Histochemical Staining of GUS Activity in Germinating Seedlings Expressing ProPGDH1:GUS, ProPGDH2:GUS, and ProPGDH3:GUS.

Supplemental Figure 8. Biotic Stress Induces PS Pathway Gene Expression.

Supplemental Figure 9. Metabolic Alterations in Roots of PGDH1-Silenced Plants and Control.

Supplemental Figure 10. Histochemical Staining of GUS Activity in Plants Expressing ProPSAT1:GUS, ProPSAT2:GUS, and ProPSP:GUS Constructs.

Supplemental Table 1. List of Genes Coexpressed with PGDH1 from the ATTED Database.

Supplemental Table 2. List of Primers Used in This Study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Diana Vogelmann (University of Cologne) for excellent technical assistance, Benjamin Buer (University of Cologne) for providing DR5:GUS lines, and Rainer Schwacke (Research Centre, Jülich), Ute Höcker (University of Cologne), and John Chandler (University of Cologne) for critical comments and discussion. This research was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinshaft (Grant Kr4245/1-1).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.M.B., K.L., S.Wulfert, S.Wittek, T.G., H.F., M.G., and S.K. performed research. T.G. and H.F. contributed analytical tools. S.K., M.G., and U.-I.F. wrote the article. U.-I.F. and S.K. designed the research.

References

- Achouri Y., Rider M.H., Schaftingen E.V., Robbi M. (1997). Cloning, sequencing and expression of rat liver 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase. Biochem. J. 323: 365–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agüera E., Ruano D., Cabello P., de la Haba P. (2006). Impact of atmospheric CO2 on growth, photosynthesis and nitrogen metabolism in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) plants. J. Plant Physiol. 163: 809–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araújo W.L., Ishizaki K., Nunes-Nesi A., Larson T.R., Tohge T., Krahnert I., Witt S., Obata T., Schauer N., Graham I.A., Leaver C.J., Fernie A.R. (2010). Identification of the 2-hydroxyglutarate and isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenases as alternative electron donors linking lysine catabolism to the electron transport chain of Arabidopsis mitochondria. Plant Cell 22: 1549–1563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauwe H., Hagemann M., Fernie A.R. (2010). Photorespiration: Players, partners and origin. Trends Plant Sci. 15: 330–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger B., Stracke R., Yatusevich R., Weisshaar B., Flügge U.I., Gigolashvili T. (2007). A simplified method for the analysis of transcription factor-promoter interactions that allows high-throughput data generation. Plant J. 50: 911–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum K., Shasha D.E., Wang J.Y., Jung J.W., Lambert G.M., Galbraith D.W., Benfey P.N. (2003). A gene expression map of the Arabidopsis root. Science 302: 1956–1960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M.M. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72: 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bräutigam A., Gagneul D., Weber A.P. (2007). High-throughput colorimetric method for the parallel assay of glyoxylic acid and ammonium in a single extract. Anal. Biochem. 362: 151–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britto D.T., Kronzucker H.J. (2002). NH4+ toxicity in higher plants: A critical review. J. Plant Physiol. 159: 567–584 [Google Scholar]

- Cairns N.G., Pasternak M., Wachter A., Cobbett C.S., Meyer A.J. (2006). Maturation of Arabidopsis seeds is dependent on glutathione biosynthesis within the embryo. Plant Physiol. 141: 446–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celenza J.L., Quiel J.A., Smolen G.A., Merrikh H., Silvestro A.R., Normanly J., Bender J. (2005). The Arabidopsis ATR1 Myb transcription factor controls indolic glucosinolate homeostasis. Plant Physiol. 137: 253–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coschigano K.T., Melo-Oliveira R., Lim J., Coruzzi G.M. (1998). Arabidopsis gls mutants and distinct Fd-GOGAT genes. Implications for photorespiration and primary nitrogen assimilation. Plant Cell 10: 741–752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denby K.J., Kumar P., Kliebenstein D.J. (2004). Identification of Botrytis cinerea susceptibility loci in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 38: 473–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey S., Hu Z., Xu X.L., Sacchettini J.C., Grant G.A. (2005). D-3-Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a link between the Escherichia coli and mammalian enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 14884–14891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douce R., Bourguignon J., Neuburger M., Rébeillé F. (2001). The glycine decarboxylase system: A fascinating complex. Trends Plant Sci. 6: 167–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn M.F. (2012). Allosteric regulation of substrate channeling and catalysis in the tryptophan synthase bienzyme complex. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 519: 154–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhut M., et al. (2013). Arabidopsis A BOUT DE SOUFFLE is a putative mitochondrial transporter involved in photorespiratory metabolism and is required for meristem growth at ambient CO₂ levels. Plant J. 73: 836–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuelsson O., Brunak S., von Heijne G., Nielsen H. (2007). Locating proteins in the cell using TargetP, SignalP and related tools. Nat. Protoc. 2: 953–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farré E.M., Tiessen A., Roessner U., Geigenberger P., Trethewey R.N., Willmitzer L. (2001). Analysis of the compartmentation of glycolytic intermediates, nucleotides, sugars, organic acids, amino acids, and sugar alcohols in potato tubers using a nonaqueous fractionation method. Plant Physiol. 127: 685–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felippes F.F., Wang J.W., Weigel D. (2012). MIGS: miRNA-induced gene silencing. Plant J. 70: 541–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flügge U.I., Heldt H.W. (1976). Identification of a protein involved in phosphate transport of chloroplasts. FEBS Lett. 68: 259–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gachon C.M., Langlois-Meurinne M., Henry Y., Saindrenan P. (2005). Transcriptional co-regulation of secondary metabolism enzymes in Arabidopsis: Functional and evolutionary implications. Plant Mol. Biol. 58: 229–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giavalisco P., Köhl K., Hummel J., Seiwert B., Willmitzer L. (2009). 13C isotope-labeled metabolomes allowing for improved compound annotation and relative quantification in liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry-based metabolomic research. Anal. Chem. 81: 6546–6551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigolashvili T., Berger B., Mock H.P., Müller C., Weisshaar B., Flügge U.I. (2007). The transcription factor HIG1/MYB51 regulates indolic glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 50: 886–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glawischnig E., Tomas A., Eisenreich W., Spiteller P., Bacher A., Gierl A. (2000). Auxin biosynthesis in maize kernels. Plant Physiol. 123: 1109–1119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant G.A. (2006). The ACT domain: A small molecule binding domain and its role as a common regulatory element. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 33825–33829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu L., Jones A.D., Last R.L. (2010). Broad connections in the Arabidopsis seed metabolic network revealed by metabolite profiling of an amino acid catabolism mutant. Plant J. 61: 579–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson A.D., Gregory J.F., III (2002). Synthesis and turnover of folates in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5: 244–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldt W.H., Werdan K., Milovancev M., Geller G. (1973). Alkalization of the chloroplast stroma caused by light-dependent proton flux into the thylakoid space. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 314: 224–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse H., Kreft O., Maimann S., Zeh M., Hoefgen R. (2004). Current understanding of the regulation of methionine biosynthesis in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 55: 1799–1808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C.L., Saito K. (2001). Molecular biology of the plastidic phosphorylated serine biosynthetic pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. Amino Acids 20: 243–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C.L., Noji M., Saito K. (1999a). Plastidic pathway of serine biosynthesis. Molecular cloning and expression of 3-phosphoserine phosphatase from Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 11007–11012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C.L., Noji M., Saito M., Saito K. (1999b). Regulation of serine biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Crucial role of plastidic 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase in non-photosynthetic tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 397–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C.L., Noji M., Saito M., Yamazaki M., Saito K. (1998). Molecular characterization of plastidic phosphoserine aminotransferase in serine biosynthesis from Arabidopsis. Plant J. 16: 443–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabrin S., Ravanel S., Gambonnet B., Douce R., Rébeillé F. (2003). One-carbon metabolism in plants. Regulation of tetrahydrofolate synthesis during germination and seedling development. Plant Physiol. 131: 1431–1439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakoby M.J., Weinl C.F., Pusch S.F., Kuijt S.J.F., Merkle T.F., Dissmeyer N., Schnittger A. (2006). Analysis of the subcellular localization, function, and proteolytic control of the Arabidopsis cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor ICK1/KRP1. Plant Physiol. 141: 1293–1305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jander G., Norris S.R., Joshi V., Fraga M., Rugg A., Yu S., Li L., Last R.L. (2004). Application of a high-throughput HPLC-MS/MS assay to Arabidopsis mutant screening; evidence that threonine aldolase plays a role in seed nutritional quality. Plant J. 39: 465–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi V., Laubengayer K.M., Schauer N., Fernie A.R., Jander G. (2006). Two Arabidopsis threonine aldolases are nonredundant and compete with threonine deaminase for a common substrate pool. Plant Cell 18: 3564–3575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliebenstein D.J., Rowe H.C., Denby K.J. (2005). Secondary metabolites influence Arabidopsis/Botrytis interactions: Variation in host production and pathogen sensitivity. Plant J. 44: 25–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koroleva O.A., Tomlinson M.L., Leader D., Shaw P., Doonan J.H. (2005). High-throughput protein localization in Arabidopsis using Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression of GFP-ORF fusions. Plant J. 41: 162–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancien M., Gadal P., Hodges M. (2000). Enzyme redundancy and the importance of 2-oxoglutarate in higher plant ammonium assimilation. Plant Physiol. 123: 817–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancien M., Martin M., Hsieh M.H., Leustek T., Goodman H., Coruzzi G.M. (2002). Arabidopsis glt1-T mutant defines a role for NADH-GOGAT in the non-photorespiratory ammonium assimilatory pathway. Plant J. 29: 347–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson C., Albertsson E. (1979). Enzymes related to serine synthesis in spinach chloroplasts. Physiol. Plant. 45: 7–10 [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D.R., Miller N.D., Splitt B.L., Wu G., Spalding E.P. (2007). Separating the roles of acropetal and basipetal auxin transport on gravitropism with mutations in two Arabidopsis multidrug resistance-like ABC transporter genes. Plant Cell 19: 1838–1850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindroth P., Mopper K. (1979). High performance liquid chromatographic determination of subpicomole amounts of amino acids by precolumn fluorescence derivatization with o-phthaldialdehyde. Anal. Chem. 51: 1667–1674 [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Savage L.J., Ajjawi I., Imre K.M., Yoder D.W., Benning C., Dellapenna D., Ohlrogge J.B., Osteryoung K.W., Weber A.P., Wilkerson C.G., Last R.L. (2008). New connections across pathways and cellular processes: Industrialized mutant screening reveals novel associations between diverse phenotypes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 146: 1482–1500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malitsky S., Blum E., Less H., Venger I., Elbaz M., Morin S., Eshed Y., Aharoni A. (2008). The transcript and metabolite networks affected by the two clades of Arabidopsis glucosinolate biosynthesis regulators. Plant Physiol. 148: 2021–2049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek L.F., Stewart C.R. (1992). Photosynthesis and photorespiration in presenescent, senescent, and rejuvenated soybean cotyledons. Plant Physiol. 98: 694–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurino V.G., Peterhansel C. (2010). Photorespiration: Current status and approaches for metabolic engineering. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 13: 249–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]