Abstract

The human body is covered with several million sweat glands. These tiny coiled tubular skin appendages produce the sweat that is our primary source of cooling and hydration of the skin. Numerous studies have been published on their morphology and physiology. Until recently, however, little was known about how glandular skin maintains homeostasis and repairs itself after tissue injury. Here, we provide a brief overview of sweat gland biology, including newly identified reservoirs of stem cells in glandular skin and their activation in response to different types of injuries. Finally, we discuss how the genetics and biology of glandular skin has advanced our knowledge of human disorders associated with altered sweat gland activity.

Millions of sweat glands cover the human body. Until recently, little was known about how this glandular skin maintains homeostasis and repairs itself after injury.

Sweating plays an important role in the regulation of human body temperature through dissipating thermal energy from the skin surface when water in the sweat evaporates. Sweat counteracts heat stress after we exercise and allows us to survive in extreme climates. Hypohidrosis (also referred to as anhidrosis) is a condition in which patients have deficient or absent sweating. On heat stress, body temperature in these patients can increase to dangerous levels leading to hyperthermia, heat exhaustion, heat stroke, and potentially death (Sato et al. 1989a; Cheshire and Freeman 2003). Conversely, hyperhidrotic patients generate excessive sweat that can cause various levels of discomfort and stress, ranging from dehydration and skin infections to social embarrassment.

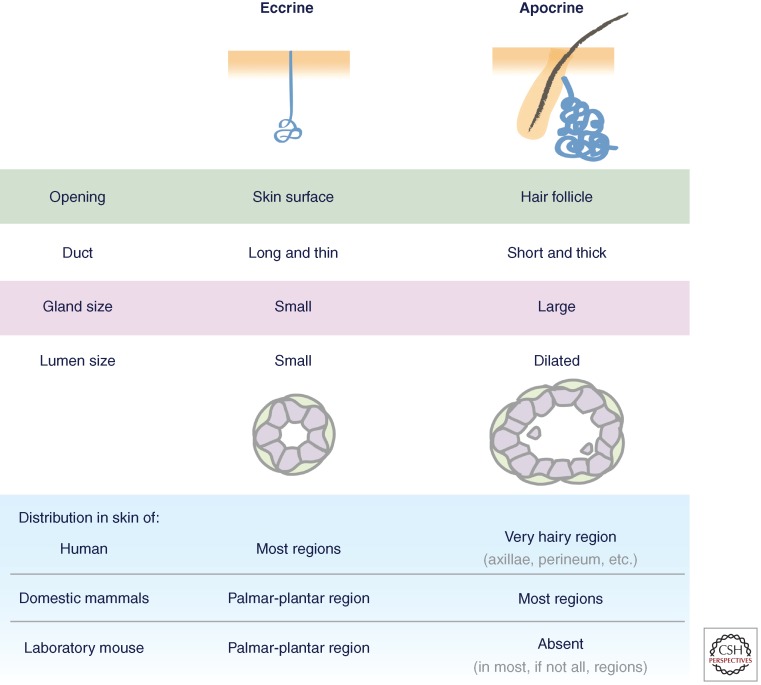

Human skin has two major types of sweat glands: eccrine and apocrine (Fig. 1). In eccrine glands, the duct opens onto the skin surface enabling the gland to secrete a water- and salt-based liquid. In contrast, the apocrine sweat gland is an appendage of the hair follicle and releases fluid through the follicle orifice. Moreover, apocrine sweat glands release an oily substance by shearing off cell parts as necrobiotic secretions (Sato et al. 1989a; Wilke et al. 2007). A third type of sweat gland, termed apoeccrine sweat gland, has been reported to exist in axillae areas of the human body (Sato et al. 1987), but, to date, this remains unsubstantiated.

Figure 1.

Features of eccrine and apocrine sweat glands. (Image adapted from Sato et al. 1987.)

In humans, eccrine sweat glands are the only ones distributed widely on the body surface with as many as ∼700/cm2 in adult skin from the palms and soles. In contrast, apocrine glands are restricted to very hairy body regions, such as axillae and perineum. The density of apocrine glands is much less compared to eccrine glands with ∼50/cm2 (or less) (Sato et al. 1989a).

Most domestic mammals lack eccrine glands over most of their body surface, and yet for many, sweating is still essential for their thermal regulation in withstanding climate and stress extremes. Horses and camels are among the best examples of working animals whose sweating function is critical for their survival and performance; they use apocrine secretion to dissipate heat (Schmidt-Nielsen et al. 1957; McEwan Jenkinson et al. 2006). Mouse, as the most commonly used laboratory animal, has eccrine sweat glands exclusively present in the pads of their paws, and its trunk skin lacks sweat glands altogether. Animals such as this are sensitive to extremes in climate.

ECCRINE SWEAT GLANDS

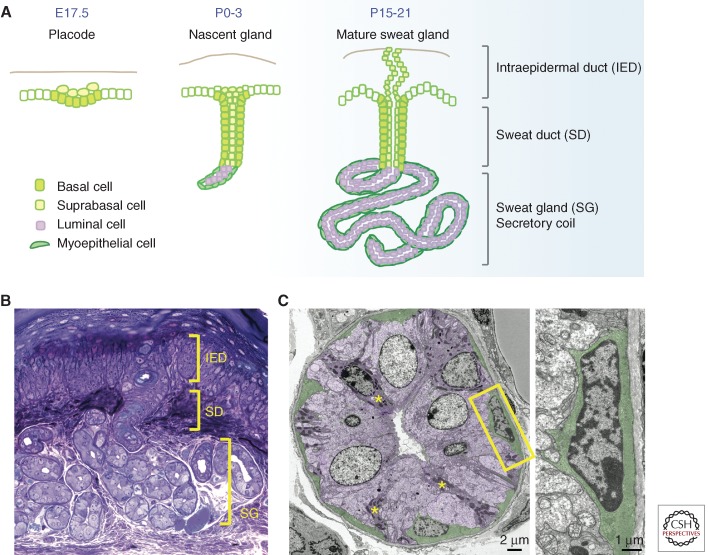

The duct of the eccrine gland is a straight channel, which distinguishes it from the branched duct of the more extensively studied mammary gland. The secretory portion of the eccrine gland also contrasts with that of the mammary gland in its distinctive, coiled tubular structure, narrow center (lumen), and secretion of sweat rather than milk. These differences aside, the overall tissue architecture is a classical bilayered gland consisting of a hollow center surrounded by an inner layer of secretory (luminal) cells, and an outer layer of myoepithelial cells encased by a basement membrane (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Development and morphology of mouse eccrine sweat glands. (A) Mouse sweat bud placodes start to form just before birth, and progenitors from the epidermal basal layer invaginate deep into dermis. As morphogenesis proceeds, cells at the tip of the down-growing sweat bud differentiate into luminal cells and myoepithelial cells of the secretory coil, whereas suprabasal cells in the duct extend upward and reach to the skin surface to form an orifice. (B) Cross-section and histology staining of a mouse paw pad where sweat apparatus are located, showing intraepidermal duct (IED), sweat duct (SD), and sweat gland (SG). (C) Ultrastructural image of a cross section of the sweat gland. Shown in purple are luminal cells containing clear cells and dark cells (asterisk). Myoepithelial cells are in green. Magnification of the boxed area is on the right, showing its spindle-like morphology, enrichment of actin filaments, and intimate contact with basement membrane. (Images courtesy of H.A. Pasolli.)

Myoepithelial cells are enriched in myofilaments and actins, suggesting that their role may be to provide contractile support to facilitate sweat secretion (Sato 1977; Sato et al. 1989a). Within the single luminal layer, there are two types of cells, clear cells and dark cells, which can be distinguished by different affinities to basic dyes and their granule contents (Montagna et al. 1953; Munger 1961). The clear cells are larger and without secretory granules, and the dark cells are smaller and rich in Schiff-reactive granules (Fig. 2). Both are responsible for producing sweat and its ingredients. Based on their histochemistry, it is thought that clear cells are mainly responsible for generating water, electrolytes, and inorganic substances in the sweat, and dark cells contribute to the secretion of macromolecules such as glycoproteins (Lobitz and Dobson 1961; Yanagawa et al. 1986). There are also various proteolytic enzymes (Horie et al. 1986) and active interleukin-1 (Reitamo et al. 1990; Sato and Sato 1994) present in the eccrine sweat, which are considered to contribute to the barrier function of the skin.

Electrolytes in the primary sweat are reabsorbed in the duct to generate hypotonic fluid before being released to the skin surface. Importantly, elevated NaCl levels in sweat, caused by defective reabsorption, is a diagnostic criterion for cystic fibrosis (CF) (Cage et al. 1966; Quinton 2007). CF patients have mutations in the gene encoding the CF transmembrane regulator (Kerem et al. 1989; Riordan et al. 1989; Rommens et al. 1989; Collins 1992; Welsh and Smith 1993), which is abundantly expressed not only in lungs, but also in eccrine sweat ducts and is critical for proper electrolyte absorption (Crawford et al. 1991; Kartner et al. 1992). Abnormal electrolyte transport across the epithelium results in thicker secretions, which in lungs, may result in lung infections and difficulty to breath.

APOCRINE SWEAT GLANDS

Apocrine glands are already present at birth, but become fully active during hormonal changes associated with puberty (Hashimoto 1970; Sato et al. 1989a). They have a thick, short duct that connects to upper hair follicles and secretes fluid into the hair canal before going to the skin surface. Apocrine sweat is a cloudy, viscous fluid containing proteins, lipids, and steroids, as well as water and electrolytes. It is initially odorless, but can be processed by bacteria (Corynebaterium striatum) to generate smaller odoriferous compounds as observed in patients with osmidrosis or bromhidrosis (Shehadeh and Kligman 1963; Preti and Leyden 2010). Recently, a single-nucleotide polymorphism 538G > A in ABCC11 gene encoding an ATP-driven transporter has been identified to associate with osmidrosis (Toyoda et al. 2009; Martin et al. 2010), suggesting that genetic variations in the secretory pathway may also be involved. It will be interesting to determine the substrates of the ABCC11 protein, which may consist of precursors of odoriferous metabolites from apocrine sweat.

The precise source of apocrine glands is still poorly understood. A priori, apocrine glands could derive from a few cells in the developing hair follicles that happen to undergo glandular transformation, a process that could be further triggered during puberty. It is intriguing to consider the different distributions of apocrine and eccrine sweat glands in the skin of mammals (Fig. 1). Although most, if not all, have eccrine sweat glands in nonhairy (glabrous) regions such as palmar-plantar skin, many animals display apocrine glands throughout much of their hairy body surface. Human is the only mammal that has eccrine glands over most of their body surface, with apocrine glands exclusively present in highly localized hairy axillary regions. Indeed, the evolution from apocrine to eccrine gland-dominant skin is one of the most important traits that humans have acquired to gain a survival advantage against the extremes of climate variations.

MORPHOGENESIS OF ECCRINE SWEAT GLANDS DURING SKIN DEVELOPMENT

Ultrastructural observations on eccrine sweat gland development in human embryos were reported back in 1960s (Hashimoto et al. 1965). In human embryos, sweat glands begin to develop from the epidermis on the palms and soles at 12–13 weeks, and on the rest of the body at 20 weeks. Myoepithelial cells and luminal cells in the secretory portion can be detected by 22 weeks. The presence of microvilli, Golgi bodies, secretory vesicles, and granules indicates that preparation for secretory function initiates in embryonic life (Sato et al. 1989a). Keratin expression analysis has also provided information on the human fetal development of eccrine sweat glands and their differentiation; luminal keratins K8 and K18 are first detected in the distal portion of the nascent sweat gland at week 15, and followed by expression of myoepithelial markers K5, K14, K17, and smooth muscle actin (SMA) at week 22 (Sun et al. 1979; Moll and Moll 1992).

Like other body sites, the basal layer of palmoplantar skin expresses K5 and K14, but in contrast to the K1 and K10 differentiating epidermal cells of body trunk skin, an additional suprabasal cell, K9, is expressed (Fuchs and Green 1980; Moll and Moll 1992). The epidermis of palmoplantar skin is also much thicker than that in other body regions. For mice, palmoplantar skin is also the only body region in which eccrine sweat glands are abundant.

Like human palmoplantar skin, mouse sweat buds first appear in fetal development. At embryonic day 17.5–18.5, K5- and K14-expressing epidermal invaginations first appear. Postnatally, as morphogenesis proceeds, the simple straight tubular structure extends deeper into the dermis and the tip of the tubule begins to coil. Maturation is completed around 2 weeks after birth and glands become fully functional by 3 weeks after birth.

As morphogenesis proceeds, cells in the inner (suprabasal) layer of the developing sweat duct gradually lose their K5/K14 expression and differentiate into K8-/K18-expressing luminal cells, whereas cells in the outer (basal) layer of the coils remain positive for K5/K14 and develop into SMA-positive myoepithelial cells. At the beginning of development, proliferation takes places exclusively in K5/K14+ basal cells and gradually transitions to K8/K18+ suprabasal cells of developing ducts and glands. Once morphogenesis is complete, proliferation is barely detectable in the mature glands, and only remains active in the basal cells of the sweat duct and the paw skin epidermis (Lu et al. 2012).

Multipotent and Unipotent Progenitors

Lineage tracing with Rosa26LacZ or Rosa26YFP transgenic mouse lines has been used extensively to mark epithelial progenitors and track their progeny (Soriano 1999; Blanpain and Simons 2013). Recently, this approach was used to unearth the existence of multipotent and unipotent progenitors in the sweat glands (Lu et al. 2012). At the initiation of sweat bud downgrowth, labeling of K14+ or K5+ basal cells will result in progeny consisting of basal cells and luminal cells in the sweat glands. These data confirm that the sweat glands are derived from multipotent epidermal basal progenitors. Labeling of emerging K15+/K18+ luminal cells followed by lineage tracing into mature glands shows that they clonally expand exclusively as luminal cells, indicating that once they form, luminal progenitors are unipotent. Similar lineage tracing of emerging myoepithelial cells shows their unipotency. These findings reveal a switch from multipotency to unipotency in the progenitor properties during the sweat gland morphogenesis.

SIGNALING PATHWAYS INVOLVED IN SWEAT GLAND DEVELOPMENT

EDA/EDAR/NF-κB Signaling Pathway

Much of what is known about signaling in sweat gland development originated from studies on human patients of HED, a disease characterized by absent or malformed hair, teeth, and sweat glands (Reed et al. 1970; Cui and Schlessinger 2006; Mikkola 2009). At the root of this disorder are genetic defects in a signaling pathway of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily. The EDA gene, encoding the ligand ectodysplasin-A, is mutated in the X-linked form of HED (Zonana et al. 1992; Kere et al. 1996); genes encoding EDA’s receptor (EDAR) and associated adaptor protein (EDARADD) are mutated in the autosomal form of HED (Monreal et al. 1999; Headon et al. 2001). Mutations in these three genes account for the majority of HED cases and cause a severe sweating defect (Chassaing et al. 2006; Cluzeau et al. 2011), indicating the indispensable requirement for EDA signaling in sweat gland development.

This knowledge arose from positional cloning of several spontaneous mouse mutant strains, namely tabby (Ta), downless (Dl), and crinkled (Cr), known for more than half a century to display HED phenotypes (Falconer 1953; Blecher 1986). These mice harbor mutations in Eda, Edar, and Edaradd genes, respectively (Ferguson et al. 1997; Srivastava et al. 1997; Monreal et al. 1999; Headon et al. 2001). More than 20 different glands are affected, and, in particular, sweat glands are absent in these mouse mutants. In addition, mice deficient for TRAF6 (TNF-receptor-associated factor 6) (Naito et al. 2002) and NF-κB activity (Schmidt-Ullrich et al. 2001) also show identical HED phenotype, guiding researchers to the realization that EDA/EDAR signals through the TRAF6 and NF-κB pathway in the development of epidermal appendages, particularly glands, teeth, and guard hairs (Döffinger et al. 2001; Kumar et al. 2001).

Various studies have been performed to transgenically express EDA/EDAR either in Eda-null (tabby) mice to rescue the HED phenotype, or in wild-type mice to examine the developmental consequences of augmenting EDA signaling. Although ubiquitous overexpression of the EDA-A1 isoform in tabby mice resulted in near complete restoration of skin appendages, including sweat glands (Srivastava et al. 2001), epithelial-specific overexpression in wild-type mice caused stimulated sweat gland function (Mustonen et al. 2003). Treatment of pregnant tabby mice with EDA-A1 recombinant protein also successfully rescued sweat gland formation in the paw skin as well as the other tissues under EDA/EDAR control (Gaide and Schneider 2003). Moreover, when transgenic mice were engineered to induce Eda-A1 gene expression on tetracycline treatment, it was discovered that EDA signaling is required for gland development only during a discrete window encompassing normal gland initiation and early mophogenesis; if not sustained throughout this time period, mature glands are not generated (Cui et al. 2009).

Interestingly, a natural EDAR variant (V370A) was found within a human population originating from East Asia that has especially thick hair and incisor tooth shoveling, that is, opposite that which is typically expected for HED (Sabeti et al. 2007; Fujimoto et al. 2008; Kimura et al. 2009). This variant is especially prevalent among the Han Chinese, Native Americans, and other populations in Japan and Thailand descended from East Asians. Although initial mouse models showed no obvious difference in sweat gland density (Mou et al. 2008; Chang et al. 2009), a recent knockin mouse expressing EDARV370A rectified this situation (Kamberov et al. 2013). Indeed, when the EDARV370A variant in the human population was analyzed, eccrine sweat gland density was higher than normal. Given that this variant arose more than 30,000 years ago and persists in an ever-expanding population, it seems likely that the increased sweat gland density confers a selective advantage in the hot and humid climate of this region. An added benefit may be the ability of this variant allele to partially attenuate the HED phenotypes caused by EDA gene mutations in human patients (Cluzeau et al. 2012).

Despite the requirement of EDA/EDAR/NF-κB signaling for the initiation, morphogenesis, and densities of epidermal appendages, their regional positioning remains largely unaffected by overactivating the pathway. Similarly, many of the distinctive characteristics of different appendages/glands are preserved even under excessive signaling. One exception may be in branching morphology, which is quite extensive in mammary and salivary glands, but is completely lacking in sweat gland or hair follicles. It has been observed that both mammary and salivary glands display defective branching in Tabby mice (Blecher et al. 1983; Häärä et al. 2011; Voutilainen et al. 2012), and ductal branching appears to be enhanced on excessive EDA/EDAR signaling (Mustonen et al. 2003; Chang et al. 2009). It will be interesting in the future to determine whether the “nonbranched” morphologies of sweat glands and hair follicles are achieved by modulating EDA/EDAR/NF-κB signaling during development.

Wnt Signaling Pathway

The reciprocal relation between EDA and Wnt signaling has been extensively studied. Because EDA and EDAR expression has been shown to be dependent on lymphoid enhancer factor 1 (Lef1), and a Lef1-binding motif was identified in the promoter region of the Eda gene, the Wnt/β-catenin/Lef1 pathway has been considered to be an upstream regulator of the EDA signaling in the development of ectodermal appendages (Kere et al. 1996; Kobielak et al. 1998; Laurikkala et al. 2001). Conversely, many studies have also shown that Wnt signaling is downstream from EDA signaling during placode formation of ectodermal appendages, such as hair follicle and tooth (Tucker et al. 2000; Cui et al. 2002; Laurikkala et al. 2002; Mikkola and Millar 2006; Fliniaux et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2009). However, among these studies, the role of Wnt signaling in the context of sweat gland development has not been directly addressed. Recently, it was reported that mutations in WNT10a account for 16% of the HED human patients, and that many of these patients show severe sweating anomalies (Cluzeau et al. 2011). On the contrary, mutations in other Wnt proteins, such as Wnt10b and Wnt6, which have been shown to be EDA/NF-κB downstream targets (Tucker et al. 2000; Zhang et al. 2009) and upstream signals (Laurikkala et al. 2002), respectively, in the context of tooth or hair follicle development, were not found in human HED patients. These findings suggest a special role for Wnt10a in sweat gland development. It will be interesting in the future to determine at which step Wnt10a is involved in sweat gland development, and the extent to which these variations in Wnt effects are attributable to differences in expression versus function.

Shh Signaling Pathway

It has been shown that during hair and tooth placode formation, induction of Shh requires EDA/NF-κB signaling (Tucker et al. 2000; Laurikkala et al. 2002; Pummila et al. 2007; Cui et al. 2011). By comparing transcriptional profiles of wild-type and Tabby foot pads where eccrine sweat glands exist, it was shown that Shh is significantly down-regulated when EDA signaling is absent (Kunisada et al. 2009). In addition, Shh expression in wild-type footpads increases beginning at E15.5, peaks at P3, and decreases as sweat glands mature, suggesting that Shh signaling participates in sweat gland development specifically during their induction and/or early progression, rather than during maturation and/or maintenance. The precise role of Shh signaling in sweat gland morphogenesis still awaits clarification.

BMP Signaling Pathway

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP) are members of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β superfamily present in the mesenchyme and are known to regulate the development of ectodermal appendages (Botchkarev and Sharov 2004). Notably, the BMP antagonist Noggin stimulates Lef1 up-regulation at the hair placode and promotes follicle formation (Botchkarev et al. 1999; Jamora et al. 2003). Intriguingly, transgenic mice overexpressing Noggin not only show increased hair density, but also a nearly complete substitution of eccrine glands by hair follicles in the normally hairless footpads (Plikus et al. 2004) and ectopic hair follicles in the normally hairless nipple epithelium (Mayer et al. 2008). These findings suggest that inhibiting BMP signaling favors hair follicle cell fates, whereas active BMP signaling promotes glandular cell fates.

Recently, Sostdc1 (Ectodin), a modulator of both Wnt and BMP pathways, was found to be essential for suppressing hair follicle fate in the normally hairless nipple (Närhi et al. 2012). Similar to K14-Noggin mice, Sostdc1-null mice develop hair follicles in the nipple epithelium. Because both Noggin and Ectodin exert BMP inhibitory effects thought to be favorable for hair follicle morphogenesis, the positive effects of loss of Ectodin function seem likely to be rooted in elevating Wnt signaling. It will be interesting to examine whether Sostdc1 is also required to suppress hair follicle fate in normally hairless footpads and whether it functions in sweat gland development.

HOMEOSTASIS AND WOUND REPAIR OF THE SWEAT APPARATUS

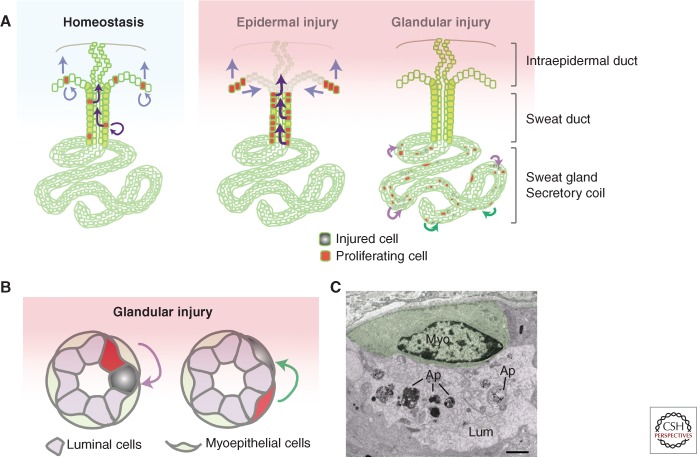

Skin injuries happen frequently in our daily lives and a rapid repairing mechanism is crucial to maintain its function as the first barrier of our bodies. Previous studies using lineage tracing and mouse models revealed that stem cells of both the epidermis and the hair follicles contribute to skin wound repair (Ito et al. 2005; Levy et al. 2007; Nowak et al. 2008; Snippert et al. 2010). Because there are more sweat glands than hair follicles in the majority area of human skin, it has been hypothesized that another source of progenitors or stem cells within the sweat apparatus (duct and gland) can contribute to skin wound repair (Brouard and Barrandon 2003; Biedermann et al. 2010). How the cells in the sweat apparatus maintain homeostasis and respond to different types of injury has been studied at the histological level. This issue has now been revisited, this time with a focus on the progenitors of glabrous palmar-plantar skin (Fig. 3) (Lu et al. 2012).

Figure 3.

Homeostasis and wound repair of mouse eccrine sweat glands. (A, left) During homeostasis, basal cells in paw epidermis and sweat ducts proliferate to self-renew and replenish the worn suprabasal epidermis and intraepidermal duct. Curved arrows, self-renew; straight arrows, differentiation and migration. (A, middle) When a large portion of epidermis is injured or removed, increased proliferation takes place in neighboring healthy basal cells of the sweat duct and epidermis. These cells (and/or their progeny) rapidly migrate and differentiate to repair the injured area. Note that cells in the sweat gland do not respond to epidermal injury. (A, right) When cells in the sweat gland are injured, the neighboring healthy cells can be activated to repair locally, shown by curved arrows. (B) During glandular injury, when luminal cells are injured, neighboring luminal cells proliferate to repair (purple curved arrow). When myoepithelial cells are injured, neighboring myoepithelial cells proliferate to repair (green curved arrow). (C) Ultrastructural image of an unresponsive myoepithelial cell (green) in close vicinity of dying luminal cells (purple). Ap, apoptotic bodies. Scale bar, 1 µm (Lu et al. 2012).

Homeostasis

During normal homeostasis of the adult sweat apparatus, mitoses are found frequently in the basal cells of the sweat ducts, but only rarely in the secretory coil of the sweat glands (Morimoto and Saga 1995). Based on such observations, it was hypothesized long ago that the sweat duct may serve as the “matrix for the replacement” of glandular cells (Lobitz et al. 1954b). Given the quiescent nature of the secretory coil, it has been a matter of speculation as to whether it contains any progenitor or stem cells involved in replenishment.

As judged from histological observations, nucleotide analog (bromodeoxyuridine) incorporation and cell-cycle marking (proliferating cell nuclear antigen), only rare signs of proliferative activity have been detected in the coil, and these have been nearly exclusively confined to the luminal layer (Morimoto and Saga 1995). With use of a more sensitive nucleotide analog (EdU) and prolonged labeling, proliferation has now been detected in both luminal and myoepithelial cell types (Lu et al. 2012), suggesting that both cell populations within the sweat glands are capable of at least limited self-renewal. In all cases, proliferation is always higher in the luminal cells, suggesting a more frequent turnover of this layer during normal homeostasis.

A transgenic mouse (pTreH2BGFP/K5tTA) was previously developed and used for identifying label-retaining cells in hair follicles (Tumbar et al. 2004). All K5+ basal cells of the epidermis, the sweat duct and sweat gland (myoepithelial cells), and their early progeny initially express the fluorescence histone. On tetracycline treatment, H2BGFP expression is silenced and cells subsequently halve their fluorescent label with each division. After several weeks of chase, all cells in the epidermis and sweat ducts lose their labeling, whereas myoepithelial cells in the sweat gland still retain the label, underscoring the quiescent nature of the myoepithelial cells of the adult sweat glands (Lu et al. 2012).

Epidermal Injury

In 1954, Lobitz et al. (1954a) used histology to examine the response of human eccrine sweat ducts to controlled superficial injury. Based on these observations, he proposed that the basal cells in the sweat ducts constitute a “growth center” for the intraepidermal sweat ducts and possess the ability to differentiate into the periductal sheath of epidermal cells as well as the highly specialized luminal cells lining the intraepidermal ducts (Lobitz et al. 1954a).

Although porcine sweat glands are apocrine and associated with hair follicles, they have been the closest animal model used to follow up on the contribution of cells in the sweat apparatus to epidermal wound repair (Miller et al. 1998). When a shallow wound (0.5 mm) was introduced, residuals of both sweat apparatus (duct and/or gland) and hair follicles appeared to participate in the healing process. When a deep wound (1.5 mm) was introduced, only parts of the sweat apparatus remained, but the wounds were still repaired. Although lineage tracings were lacking, these studies provide suggestive evidence that cells within the sweat apparatus are capable of reepithelializing the skin surface after epidermal injury. In another study, organotypic cultures prepared from dermal fibroblasts and cells from human sweat apparatus (ducts and glands) were engrafted onto the back skins of immunodeficient rats (Biedermann et al. 2010). The emergence of a normal humanized stratified epidermis again pointed to the existence of self-renewing cells within the sweat apparatus that can contribute to epidermal wound repair.

With the advent of genetically tagged lineage-tracing technology (Soriano 1999), new mouse models permitted definitive assessment (Lu et al. 2012). Marked cells from the eccrine sweat ducts migrated upward to repair the epidermis within 3 days after a superficial scratch wound. Intraepidermal sweat ducts were reconstructed within 2 weeks. Notably, these reconstructed ducts were derived from cells of the sweat apparatus and not epidermis. Moreover, only basal progenitors within sweat ducts, and not the secretory portion of glands, responded and proliferated to repairing the duct orifice after injury (Lu et al. 2012). These results provide compelling evidence in support of the notion that the sweat duct is the “growth center” that repairs the ductal orifice that extends through the epidermis to the skin surface.

A more recent study readdressed this issue, this time using human skin (Rittié et al. 2013). By immunohistochemistry and computer-assisted three-dimensional reconstruction, these researchers concluded that eccrine sweat “glands” contribute significantly to re-epithelialization after partial-thickness wounds. In this study, proliferation within the secretory portion of the sweat gland was not examined. Without making this distinction in the analyses, it seems most likely that the contribution was primarily within the eccrine duct rather than the actual gland itself. Regardless, these findings show that, as in mice, the human sweat apparatus plays an active role in epidermal wound repair.

Glandular Injury

More than a half-century ago, Lobitz et al. (1954a,b) performed deep wounding on patient volunteers, subjected to deep excisions of large portions of trunk skin (Lobitz and Dobson 1957). During the extended period of wound-repair, the re-epithelializing tissue displayed considerable signs of epidermal acanthosis and distorted intraepidermal sweat ducts. Because sweat tests were not performed, it is not possible to judge whether these sweat apparati were fully functional. However, histological signs of mitoses deep within the wounded skin provided suggestive evidence that cells within the damaged sweat glands themselves may have the capacity to respond to deep injury and participate in regenerating the sweat duct and epidermis. Relevant to these studies are those involving wound repair in response to burns. Although second- and third-degree (full-thickness) burns may cause failure of a complete regeneration under hypertrophic scar (Fu et al. 2005), sweat glands in the ischemic zones of deep partial-thickness burns may have just minor injury such as sporadic apoptosis in the glands (Gravante et al. 2006).

Because severe skin injuries involve gross disruption to the overall tissue architecture, it has been difficult to evaluate how local injuries to sweat glands are repaired and whether the gland itself is able to generate new luminal or myoepithelial cells when old ones die. By using a genetic tool to activate expression of the diphtheria toxin receptor in specific cell populations of the sweat apparatus, and then selectively killing a subset of each population with diphtheria toxin (DT) (Buch et al. 2005), these important issues have now begun to be addressed (Lu et al. 2012). Interestingly, when a fraction of myoepithelial cells were selectively targeted for obliteration, only the surrounding healthy myoepithelial cells responded, proliferated, and repaired the damaged layer; similarly, when a subset of luminal cells were targeted, only luminal cells responded, proliferating and repairing the damaged lumen. Importantly, as visualized by the iodine-starch method (Wada 1950; Sato and Sato 1990), sweating was restored several days after terminating the DT treatment (Lu et al. 2012). These results show that both luminal and myoepithelial cells in the secretory coil of the sweat glands have the potential to exit their quiescence and respond to glandular injury, and importantly, they function as unipotent progenitors during glandular repair (Fig. 3).

SWEAT GLAND REGENERATION

Treatment of severe and extensive burns often involves skin grafting using epidermal sheets prepared from small areas of the patient’s unburned skin. Although the epidermis is restored beautifully, the sweat glands do not regenerate; therefore, heat intolerance is often expected in large-scale deep-burn survivors. Various attempts have been made to regenerate sweat glands from other epithelial cell types. Young human epidermal keratinocytes can invade collagen gels and form eccrine duct-like structures in the presence of fibroblasts, added growth factors, and serum (Shikiji et al. 2003). As yet, unidentified regional dermal components are known to be essential during embryogenesis for specifying the type of skin appendages (Stuart and Moscona 1967; Sawyer et al. 1972; Dhouailly 1973; Dhouailly et al. 1978). With this knowledge, rabbit corneal basal cells were combined with mouse embryonic plantar dermis and grafted into kidney capsules (Ferraris et al. 2000). The presence of sweat glands from the rabbit corneal basal cells was promising, but only embryonic mesenchyme has these inductive powers, posing a logistic problem for the clinics until this process is understood at a molecular level.

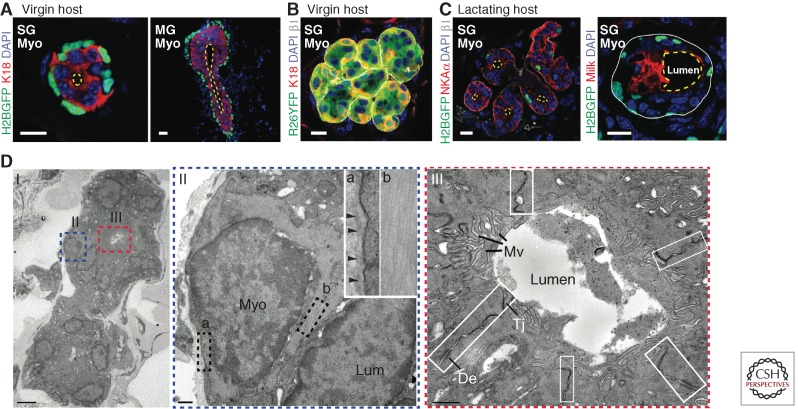

In the last decade, in vivo transplantation had been used to assess the regenerative potential at a single-cell level for various ectodermal appendages, such as hair follicle (Blanpain et al. 2004), mammary gland (Shackleton et al. 2006; Stingl et al. 2006), and salivary gland (Lombaert et al. 2008). Exploiting fluorescent activating cell sorting (FACS) based on cell-surface markers, different cell populations from the mouse sweat glands and sweat ducts can now be purified and studied individually for their regenerative capacity in engraftment experiments (Lu et al. 2012). Intriguingly, despite their unipotent behavior in the adult gland, purified myoepithelial cells consistently undergo complete de novo glandular morphogenesis when grafted into cleared mammary fat pads or interscapular (shoulder) fat pads. Moreover, when myoepithelial cells are purified from adult sweat glands, they recreate adult sweat glands, and when they are purified from adult mammary glands, they make mammary glands (Fig. 4A) (Shackleton et al. 2006; Stingl et al. 2006; Van Keymeulen et al. 2011; Lu et al. 2012). These findings suggest that myoepithelial cells retain multipotent (bipotent) potential that can be unleashed when challenged to de novo morphogenesis.

Figure 4.

De novo sweat gland formation by engraftment of myoepithelial cells purified from adult sweat glands. (A) K14H2BGFP myoepithelial cells purified from adult sweat glands (SG, left) and adult mammary glands (MG, right) show distinct morphology on engraftment. SG myoepithelial cells form a single luminal (K18+) layer and a small lumen; MG myoepithelial cells form multiple layers of luminal cells and an elongated lumen resembling the structure of terminal end buds. Yellow dashed lines outline the lumens. (B) Long-term graft of sweat gland myoepithelial cells form nonbranched, tightly tangled coil structure. Myoepithelial cells purified from Rosa26-YFP transgenic mice that allow lineage tracing gave rise to the entire structure, including K18+ luminal cells. (C) In a lactating host, grafts derived from sweat gland myoepithelial cells undergo transdifferentiation. (Left) Example of a graft that still expresses sweat gland marker (NKAα, ATP1a1) albeit lower than original level, but shows branching morphology. (Right) Example of a graft that loses NKAα expression, but starts to express milk protein (mammary gland marker) and its lumen is significantly enlarged. White solid line, basement membrane; yellow dashed line, lumen. Scale bars, 10 µm. (D) Ultrastructural analysis of a de novo glandular structure derived from purified sweat gland myoepithelial cells. Boxed areas are shown on the right. II, showing a myoepithelial cell, attaches to basement membrane (box a) and enriches in actin filament bundles (box b). III, magnification of a lumen, showing presence of microvilli (Mv). Intercellular junctions are boxed, showing desmosomes (De) and tight junction (Tj). Scale bars, 500 nm (Lu et al. 2012).

Another interesting feature unveiled by these studies is that adult myoepithelial cells retain an identity memory, likely epigenetic in nature, to build the correct gland type even when placed in a foreign environment. When taken together with the mesenchymal influence of embryonic tissue, these findings suggest that once the mesenchyme exerts its inductive powers on gland-type specification, this memory is passed on, at least transiently, through several rounds of tissue regeneration. That said, this identity can be altered in response to certain environmental cues, as exemplified by the fact that sweat gland myoepithelial grafts can undergo morphological changes and express both milk and sweat gland proteins when the mammary fat pad is from a lactating host (Fig. 4C) (Lu et al. 2012). Another example of adult progenitor fate plasticity is the ability of purified eccrine myoepithelial cells to make epidermis when engrafted to back skin (Biedermann et al. 2010; Lu et al. 2012). Given these findings, it is intriguing that adult progenitors behave so unilaterally in their native settings. Although further experiments will need to be performed to dissect the molecular reasons, it seems likely that local tissue cells impose a highly restrictive microenvironment that ensures appropriate behavior of progenitors during normal homeostasis.

SWEAT GLAND DISORDERS AND CARCINOMAS

Sweating disorders can be categorized by the amount of sweat produced: anhidrosis (absent sweating), hypohidrosis (decreased sweating), and hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating) (Quinton 1983; Sato et al. 1989b). As previously mentioned, hypohidrotic/anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (HED) is a rare hereditary genetic disease caused by defects in the development of ectodermal appendages and characterized by little or no sweat that can be produced by patients. Hypohidrosis and anhidrosis also occur when sweat glands are damaged and undergo necrosis if they fail to repair. Common causes are burns, irradiation, inflammation, chemical treatment, and wounds (Cheshire and Freeman 2003). Various systemic dermatological diseases, such as psoriasis, scleroderma, erythroderma, ichthyosis, can also affect sweat gland integrity and function. In psoriatic skin, for instance, the sweat duct becomes blocked, most likely caused by hyperplasia obstructing the orifice (Shuster and Johnson 1969). Miliaria (also called sweat rash or prickly heat), on the other hand, is a disease specific to eccrine sweat ducts and sweat glands. It can be caused by friction, overheating, or blockage of sweat ducts by skin and bacterial debris. Environmental factors, such as excessive exposure to heat and humidity, often trigger the disease onset. Based on the level of sweat retention and tissue obstruction, miliaria is classified into three types: miliaria crystalline, with ductal obstruction in the superficial stratum corneum; miliaria rubra, with obstruction deeper within the sweat duct and causing local inflammation and skin redness; and miliaria profunda, with damage deep in the sweat gland and most severe in phenotype (Dobson and Lobitz 1957; Wenzel and Horn 1998). When a significant portion of the body surface is affected, these patients risk heat exhaustion caused by ineffective sweating.

Because sweat glands are extensively innervated by sympathetic nerves and their output relies on nerve stimulation, hypohidrosis or anhidrosis sometimes results from neurological disorders that involve the central or peripheral nervous systems. This happens, for instance, in Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, diabetic neuropathy, autoimmune autonomic neuropathy, amyloid neuropathy, and many other neuropathies (Sato et al. 1989b; Cheshire and Freeman 2003). Similarly, excessive sweating can also be the consequence of overstimulation of the nervous system. It is peculiar that hyperhidrosis occurs most commonly in human axillary and palmar-plantar areas where the sweating is controlled by emotional stimuli rather than thermoregulation. Local hyperhidrosis is usually benign and at most results in discomfort; however, systemic hyperhidrosis may be accompanied by serious damage or disorders in the nervous system and have more adverse effects, such as dehydration and acute lowering of body temperature.

Sweat gland carcinomas are rare, typically age-related, malignant neoplasms that display a high rate of metastasis and recurrence (el-Domeiri et al. 1971; Wertkin and Bauer 1976; Brichkov et al. 2004). Local lymph nodes are common metastatic sites of sweat gland carcinomas, but distal metastasis into lung, liver, and bone can occur (Osaki et al. 1994; Ashley et al. 1997; Falkenstern-Ge et al. 2013). At present, little is known about the pathogenesis and molecular basis of sweat gland tumors. p53 mutations are likely involved based on sequencing (five of 16 samples) (Biernat et al. 1998), as well as loss of heterozygosity confined to the chromosome arm 17p (three of 21 sweat gland carcinoma samples) (Takata et al. 2000).

Unlike cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas, 90% of which contain p53 mutations likely triggered by ultraviolet radiation and sunburn (Ziegler et al. 1994), the lower incidence of p53 mutations in sweat gland carcinomas is likely reflective of their deeper skin location, providing them greater protection from UV light and other potential environmental mutagens. That said, this cannot be the single overriding force as both mammary glands and sweat glands show a deeper location and are protected from the sun’s harmful rays, and yet breast cancers are prevalent, whereas sweat glands are exceedingly rare. Although many features are shared between these two gland types, one that is not is the activity of its resident gland progenitors. The quiescent feature of sweat gland progenitors and their mobilization, primarily in response to deep wounds, contrasts strikingly with the tremendous branching and leafing morphogenesis that the mammary gland undergoes during pregnancy.

The lack of extensive studies has left pathologists with a paucity of diagnostic markers. It is particularly difficult to distinguish primary sweat gland carcinomas from cutaneous metastases of breast carcinomas because of their similar morphology and origins as epidermal appendages (Rollins-Raval et al. 2011; Ellis et al. 2012). Additionally, overexpression of the ERBB-2 oncogene, a common marker for aggressive breast cancers, has also been detected in some sweat gland carcinomas (Hasebe et al. 1994; Takata et al. 2000). Similarly, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, gross cystic disease fluid protein-15 express in both cases, and at best, markers appear to be more abundantly expressed in one cancer or the other (Wallace et al. 1995; Wick et al. 1998; Busam et al. 1999; Hiatt et al. 2004; Rollins-Raval et al. 2011). Currently, the primary distinguishing feature is the frequency with which these two cancers arise. However, because prognosis and treatment for these two types of carcinomas are different, it is of clinical importance to identify more reliable molecular markers to distinguish between the two.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Because of its importance to human survival, sweat glands have been a topic of intensive histological and physiological studies for many decades. The application of modern molecular biology and genetics have lagged behind, largely because human is the only species with extensive eccrine glands over the entire body surface. With the advent of lineage-tracing, nucleotide-labeling techniques, FACS, and the ability to perform transcriptional profiling on small populations of cells, the first detailed pictures of the molecular properties and potency of stem cells within glandular skin have emerged. Building on this knowledge, further exploration of molecular mechanisms that govern sweat gland activity and behavior during normal homeostasis and wound repair will be accelerated. Such discoveries should contribute greatly to our future understanding of the pathological bases of sweat gland disorders, including cancers. With such knowledge will surely come new clinical tools for the diagnosis and therapeutics of these conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by grants to E.F. (National Institutes of Health NIAMS R01AR050452 and New York State Department of Health NYSTEM/C026427) and C.L. (National Institutes of Health 5F32AR060654-03).

Footnotes

Editors: Anthony E. Oro and Fiona M. Watt

Additional Perspectives on The Skin and Its Diseases available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

- Ashley I, Smith-Reed M, Chernys A 1997. Sweat gland carcinoma. Case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg 23: 129–133 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biedermann T, Pontiggia L, Böttcher-Haberzeth S, Tharakan S, Braziulis E, Schiestl C, Meuli M, Reichmann E 2010. Human eccrine sweat gland cells can reconstitute a stratified epidermis. J Invest Dermatol 130: 1996–2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biernat W, Peraud A, Wozniak L, Ohgaki H 1998. p53 mutations in sweat gland carcinomas. Int J Cancer 76: 317–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpain C, Simons BD 2013. Unravelling stem cell dynamics by lineage tracing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 14: 489–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpain C, Lowry WE, Geoghegan A, Polak L, Fuchs E 2004. Self-renewal, multipotency, and the existence of two cell populations within an epithelial stem cell niche. Cell 118: 635–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blecher SR 1986. Anhidrosis and absence of sweat glands in mice hemizygous for the Tabby gene: Supportive evidence for the hypothesis of homology between Tabby and human anhidrotic (hypohidrotic) ectodermal dysplasia (Christ-Siemens-Touraine syndrome). J Invest Dermatol 87: 720–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blecher SR, Debertin M, Murphy JS 1983. Pleiotropic effect of Tabby gene on epidermal growth factor-containing cells of mouse submandibular gland. Anat Rec 207: 25–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev VA, Sharov AA 2004. BMP signaling in the control of skin development and hair follicle growth. Differentiation 72: 512–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev VA, Botchkareva NV, Roth W, Nakamura M, Chen LH, Herzog W, Lindner G, McMahon JA, Peters C, Lauster R, et al. 1999. Noggin is a mesenchymally derived stimulator of hair-follicle induction. Nat Cell Biol 1: 158–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brichkov I, Daskalakis T, Rankin L, Divino C 2004. Sweat gland carcinoma. Am Surg 70: 63–66 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouard M, Barrandon Y 2003. Controlling skin morphogenesis: Hope and despair. Curr Opin Biotechnol 14: 520–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buch T, Heppner FL, Tertilt C, Heinen TJ, Kremer M, Wunderlich FT, Jung S, Waisman A 2005. A Cre-inducible diphtheria toxin receptor mediates cell lineage ablation after toxin administration. Nat Methods 2: 419–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busam KJ, Tan LK, Granter SR, Kohler S, Junkins-Hopkins J, Berwick M, Rosen PP 1999. Epidermal growth factor, estrogen, and progesterone receptor expression in primary sweat gland carcinomas and primary and metastatic mammary carcinomas. Mod Pathol 12: 786–793 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cage GW, Dobson RL, Waller R 1966. Sweat gland function in cystic fibrosis. J Clin Invest 45: 1373–1378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SH, Jobling S, Brennan K, Headon DJ 2009. Enhanced Edar signalling has pleiotropic effects on craniofacial and cutaneous glands. PLoS ONE 4: e7591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassaing N, Bourthoumieu S, Cossee M, Calvas P, Vincent M-C 2006. Mutations in EDAR account for one-quarter of non-ED1-related hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Hum Mutat 27: 255–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheshire WP, Freeman R 2003. Disorders of sweating. Semin Neurol 23: 399–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluzeau C, Hadj-Rabia S, Jambou M, Mansour S, Guigue P, Masmoudi S, Bal E, Chassaing N, Vincent M-C, Viot G, et al. 2011. Only four genes (EDA1, EDAR, EDARADD, and WNT10A) account for 90% of hypohidrotic/anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia cases. Hum Mutat 32: 70–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluzeau C, Hadj-Rabia S, Bal E, Clauss F, Munnich A, Bodemer C, Headon D, Smahi A 2012. The EDAR370A allele attenuates the severity of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia caused by EDA gene mutation. Br J Dermatol 166: 678–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins FS 1992. Cystic fibrosis: Molecular biology and therapeutic implications. Science 256: 774–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford I, Maloney PC, Zeitlin PL, Guggino WB, Hyde SC, Turley H, Gatter KC, Harris A, Higgins CF 1991. Immunocytochemical localization of the cystic fibrosis gene product CFTR. Proc Natl Acad Sci 88: 9262–9266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui C-Y, Schlessinger D 2006. EDA signaling and skin appendage development. Cell Cycle 5: 2477–2483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui C-Y, Durmowicz M, Tanaka TS, Hartung AJ, Tezuka T, Hashimoto K, Ko MSH, Srivastava AK, Schlessinger D 2002. EDA targets revealed by skin gene expression profiles of wild-type, Tabby and Tabby EDA-A1 transgenic mice. Hum Mol Genet 11: 1763–1773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui C-Y, Kunisada M, Esibizione D, Douglass EG, Schlessinger D 2009. Analysis of the temporal requirement for eda in hair and sweat gland development. J Invest Dermatol 129: 984–993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui C-Y, Kunisada M, Childress V, Michel M, Schlessinger D 2011. Shh is required for Tabby hair follicle development. Cell Cycle 10: 3379–3386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhouailly D 1973. Dermo-epidermal interactions between birds and mammals: Differentiation of cutaneous appendages. J Embryol Exp Morphol 30: 587–603 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhouailly D, Rogers GE, Sengel P 1978. The specification of feather and scale protein synthesis in epidermal-dermal recombinations. Dev Biol 65: 58–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson RL, Lobitz WC 1957. Some histochemical observations on the human eccrine sweat glands: II. The pathogenesis of miliaria. AMA Arch Derm 75: 653–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Döffinger R, Smahi A, Bessia C, Geissmann F, Feinberg J, Durandy A, Bodemer C, Kenwrick S, Dupuis-Girod S, Blanche S, et al. 2001. X-linked anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia with immunodeficiency is caused by impaired NF-κB signaling. Nat Genet 27: 277–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Domeiri AA, Brasfield RD, Huvos AG, Strong EW 1971. Sweat gland carcinoma: A clinico-pathologic study of 83 patients. Ann Surg 173: 270–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis LZ, Prado R, High W, Robinson WA, Mellette JR 2012. Sweat gland carcinoma versus metastatic breast carcinoma: A continued struggle among clinicians and dermatopathologists. J Am Acad Dermatol 67: e156–e157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconer DS 1953. Total sex-linkage in the house mouse. Z Indukt Abstamm Vererbungsl 85: 210–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenstern-Ge RF, Bode-Erdmann S, Ott G, Wohlleber M, Kohlhäufl M 2013. Late lung metastasis of a primary eccrine sweat gland carcinoma 10 years after initial surgical treatment: The first clinical documentation. Case Rep Oncol Med 2013: 167585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson BM, Brockdorff N, Formstone E, Ngyuen T, Kronmiller JE, Zonana J 1997. Cloning of Tabby, the murine homolog of the human EDA gene: Evidence for a membrane-associated protein with a short collagenous domain. Hum Mol Genet 6: 1589–1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraris C, Chevalier G, Favier B, Jahoda CA, Dhouailly D 2000. Adult corneal epithelium basal cells possess the capacity to activate epidermal, pilosebaceous and sweat gland genetic programs in response to embryonic dermal stimuli. Development 127: 5487–5495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliniaux I, Mikkola ML, Lefebvre S, Thesleff I 2008. Identification of dkk4 as a target of Eda-A1/Edar pathway reveals an unexpected role of ectodysplasin as inhibitor of Wnt signalling in ectodermal placodes. Dev Biol 320: 60–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X-B, Sun T-Z, Li X-K, Sheng Z-Y 2005. Morphological and distribution characteristics of sweat glands in hypertrophic scar and their possible effects on sweat gland regeneration. Chin Med J 118: 186–191 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E, Green H 1980. Changes in keratin gene expression during terminal differentiation of the keratinocyte. Cell 19: 1033–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto A, Ohashi J, Nishida N, Miyagawa T, Morishita Y, Tsunoda T, Kimura R, Tokunaga K 2008. A replication study confirmed the EDAR gene to be a major contributor to population differentiation regarding head hair thickness in Asia. Hum Genet 124: 179–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaide O, Schneider P 2003. Permanent correction of an inherited ectodermal dysplasia with recombinant EDA. Nat Med 9: 614–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravante G, Palmieri MB, Esposito G, Delogu D, Santeusanio G, Filingeri V, Montone A 2006. Apoptotic cells are present in ischemic zones of deep partial-thickness burns. J Burn Care Res 27: 688–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häärä O, Fujimori S, Schmidt-Ullrich R, Hartmann C, Thesleff I, Mikkola ML 2011. Ectodysplasin and Wnt pathways are required for salivary gland branching morphogenesis. Development 138: 2681–2691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasebe T, Mukai K, Yamaguchi N, Ishihara K, Kaneko A, Takasaki Y, Shimosato Y 1994. Prognostic value of immunohistochemical staining for proliferating cell nuclear antigen, p53, and c-erbB-2 in sebaceous gland carcinoma and sweat gland carcinoma: Comparison with histopathological parameter. Mod Pathol 7: 37–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K 1970. The ultrastructure of the skin of human embryos: VII. Formation of the apocrine gland. Acta Derm Venereol 50: 241–251 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Gross BG, Lever WF 1965. The ultrastructure of the skin of human embryos: I. The intraepidermal eccrine sweat duct. J Invest Dermatol 45: 139–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headon DJ, Emmal SA, Ferguson BM, Tucker AS, Justice MJ, Sharpe PT, Zonana J, Overbeek PA 2001. Gene defect in ectodermal dysplasia implicates a death domain adapter in development. Nature 414: 913–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt KM, Pillow JL, Smoller BR 2004. Her-2 expression in cutaneous eccrine and apocrine neoplasms. Mod Pathol 17: 28–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie N, Yokozeki H, Sato K 1986. Proteolytic enzymes in human eccrine sweat: A screening study. Am J Physiol 250: R691–R698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Liu Y, Yang Z, Nguyen J, Liang F, Morris RJ, Cotsarelis G 2005. Stem cells in the hair follicle bulge contribute to wound repair but not to homeostasis of the epidermis. Nat Med 11: 1351–1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamora C, DasGupta R, Kocieniewski P, Fuchs E 2003. Links between signal transduction, transcription and adhesion in epithelial bud development. Nature 422: 317–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamberov YG, Wang S, Tan J, Gerbault P, Wark A, Tan L, Yang Y, Li S, Tang K, Chen H, et al. 2013. Modeling recent human evolution in mice by expression of a selected EDAR variant. Cell 152: 691–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kartner N, Augustinas O, Jensen TJ, Naismith AL, Riordan JR 1992. Mislocalization of delta F508 CFTR in cystic fibrosis sweat gland. Nat Genet 1: 321–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kere J, Srivastava AK, Montonen O, Zonana J, Thomas N, Ferguson B, Munoz F, Morgan D, Clarke A, Baybayan P, et al. 1996. X-linked anhidrotic (hypohidrotic) ectodermal dysplasia is caused by mutation in a novel transmembrane protein. Nat Genet 13: 409–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerem B, Rommens JM, Buchanan JA, Markiewicz D, Cox TK, Chakravarti A, Buchwald M, Tsui LC 1989. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: Genetic analysis. Science 245: 1073–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura R, Yamaguchi T, Takeda M, Kondo O, Toma T, Haneji K, Hanihara T, Matsukusa H, Kawamura S, Maki K, et al. 2009. A common variation in EDAR is a genetic determinant of shovel-shaped incisors. Am J Hum Genet 85: 528–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobielak K, Kobielak A, Limon J, Trzeciak WH 1998. Mutation in the regulatory region of the EDA gene coincides with the symptoms of anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Acta Biochim Pol 45: 245–250 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Eby MT, Sinha S, Jasmin A, Chaudhary PM 2001. The ectodermal dysplasia receptor activates the nuclear factor-κB, JNK, and cell death pathways and binds to ectodysplasin A. J Biol Chem 276: 2668–2677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunisada M, Cui C-Y, Piao Y, Ko MSH, Schlessinger D 2009. Requirement for Shh and Fox family genes at different stages in sweat gland development. Hum Mol Genet 18: 1769–1778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurikkala J, Mikkola M, Mustonen T, Aberg T, Koppinen P, Pispa J, Nieminen P, Galceran J, Grosschedl R, Thesleff I 2001. TNF signaling via the ligand-receptor pair ectodysplasin and edar controls the function of epithelial signaling centers and is regulated by Wnt and activin during tooth organogenesis. Dev Biol 229: 443–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurikkala J, Pispa J, Jung H-S, Nieminen P, Mikkola M, Wang X, Saarialho-Kere U, Galceran J, Grosschedl R, Thesleff I 2002. Regulation of hair follicle development by the TNF signal ectodysplasin and its receptor Edar. Development 129: 2541–2553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy V, Lindon C, Zheng Y, Harfe BD, Morgan BA 2007. Epidermal stem cells arise from the hair follicle after wounding. FASEB J 21: 1358–1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobitz WC, Dobson RL 1957. Responses of the secretory coil of the human eccrine sweat gland to controlled injury. J Invest Dermatol 28: 105–119; discussion, 119–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobitz WC, Dobson RL 1961. Dermatology: The eccrine sweat glands. Annu Rev Med 12: 289–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobitz WC, Holyoke JB, Montagna W 1954a. Responses of the human eccrine sweat duct to controlled injury: Growth center of the epidermal sweat duct unit. J Invest Dermatol 23: 329–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobitz WC, Holyoke JB, Montagna W 1954b. The epidermal eccrine sweat duct unit; a morphologic and biologic entity. J Invest Dermatol 22: 157–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombaert IMA, Brunsting JF, Wierenga PK, Faber H, Stokman MA, Kok T, Visser WH, Kampinga HH, de Haan G, Coppes RP 2008. Rescue of salivary gland function after stem cell transplantation in irradiated glands. PLoS ONE 3: e2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu CP, Polak L, Rocha AS, Pasolli HA, Chen S-C, Sharma N, Blanpain C, Fuchs E 2012. Identification of stem cell populations in sweat glands and ducts reveals roles in homeostasis and wound repair. Cell 150: 136–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, Saathoff M, Kuhn F, Max H, Terstegen L, Natsch A 2010. A functional ABCC11 allele is essential in the biochemical formation of human axillary odor. J Invest Dermatol 130: 529–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer JA, Foley J, De La Cruz D, Chuong CM, Widelitz R 2008. Conversion of the nipple to hair-bearing epithelia by lowering bone morphogenetic protein pathway activity at the dermal-epidermal interface. Am J Pathol 173: 1339–1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwan Jenkinson D, Elder HY, Bovell DL 2006. Equine sweating and anhidrosis: Part 1. Equine sweating. Vet Dermatol 17: 361–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkola ML 2009. Molecular aspects of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Am J Med Genet A 149A: 2031–2036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkola ML, Millar SE 2006. The mammary bud as a skin appendage: Unique and shared aspects of development. J Mamm Gland Biol Neoplasia 11: 187–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SJ, Burke EM, Rader MD, Coulombe PA, Lavker RM 1998. Re-epithelialization of porcine skin by the sweat apparatus. J Invest Dermatol 110: 13–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll I, Moll R 1992. Changes of expression of intermediate filament proteins during ontogenesis of eccrine sweat glands. J Invest Dermatol 98: 777–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monreal AW, Ferguson BM, Headon DJ, Street SL, Overbeek PA, Zonana J 1999. Mutations in the human homologue of mouse dl cause autosomal recessive and dominant hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Nat Genet 22: 366–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagna W, Chase HB, Lobitz WC 1953. Histology and cytochemistry of human skin: IV. The eccrine sweat glands. J Invest Dermatol 20: 415–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto Y, Saga K 1995. Proliferating cells in human eccrine and apocrine sweat glands. J Histochem Cytochem 43: 1217–1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mou C, Thomason HA, Willan PM, Clowes C, Harris WE, Drew CF, Dixon J, Dixon MJ, Headon DJ 2008. Enhanced ectodysplasin-A receptor (EDAR) signaling alters multiple fiber characteristics to produce the East Asian hair form. Hum Mutat 29: 1405–1411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger BL 1961. The ultrastructure and histophysiology of human eccrine sweat glands. J Biophys Biochem Cytol 11: 385–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustonen T, Pispa J, Mikkola ML, Pummila M, Kangas AT, Pakkasjärvi L, Jaatinen R, Thesleff I 2003. Stimulation of ectodermal organ development by Ectodysplasin-A1. Dev Biol 259: 123–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito A, Yoshida H, Nishioka E, Satoh M, Azuma S, Yamamoto T, Nishikawa S-I, Inoue J-I 2002. TRAF6-deficient mice display hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 8766–8771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Närhi K, Tummers M, Ahtiainen L, Itoh N, Thesleff I, Mikkola ML 2012. Sostdc1 defines the size and number of skin appendage placodes. Dev Biol 364: 149–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak JA, Polak L, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E 2008. Hair follicle stem cells are specified and function in early skin morphogenesis. Cell Stem Cell 3: 33–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osaki T, Kodate M, Nakanishi R, Mitsudomi T, Shirakusa T 1994. Surgical resection for pulmonary metastases of sweat gland carcinoma. Thorax 49: 181–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plikus M, Wang WP, Liu J, Wang X, Jiang T-X, Chuong C-M 2004. Morpho-regulation of ectodermal organs: Integument pathology and phenotypic variations in K14-Noggin engineered mice through modulation of bone morphogenic protein pathway. Am J Pathol 164: 1099–1114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preti G, Leyden JJ 2010. Genetic influences on human body odor: From genes to the axillae. J Invest Dermatol 130: 344–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pummila M, Fliniaux I, Jaatinen R, James MJ, Laurikkala J, Schneider P, Thesleff I, Mikkola ML 2007. Ectodysplasin has a dual role in ectodermal organogenesis: Inhibition of Bmp activity and induction of Shh expression. Development 134: 117–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinton PM 1983. Sweating and its disorders. Annu Rev Med 34: 429–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinton PM 2007. Cystic fibrosis: Lessons from the sweat gland. Physiology 22: 212–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed WB, Lopez DA, Landing B 1970. Clinical spectrum of anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Arch Dermatol 102: 134–143 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitamo S, Anttila HS, Didierjean L, Saurat JH 1990. Immunohistochemical identification of interleukin Iα and β in human eccrine sweat-gland apparatus. Br J Dermatol 122: 315–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, Zielenski J, Lok S, Plavsic N, Chou JL 1989. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: Cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science 245: 1066–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittié L, Sachs DL, Orringer JS, Voorhees JJ, Fisher GJ 2013. Eccrine sweat glands are major contributors to reepithelialization of human wounds. Am J Pathol 182: 163–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins-Raval M, Chivukula M, Tseng GC, Jukic D, Dabbs DJ 2011. An immunohistochemical panel to differentiate metastatic breast carcinoma to skin from primary sweat gland carcinomas with a review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 135: 975–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommens JM, Iannuzzi MC, Kerem B, Drumm ML, Melmer G, Dean M, Rozmahel R, Cole JL, Kennedy D, Hidaka N 1989. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: Chromosome walking and jumping. Science 245: 1059–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabeti PC, Varilly P, Fry B, Lohmueller J, Hostetter E, Cotsapas C, Xie X, Byrne EH, McCarroll SA, Gaudet R, et al. 2007. Genome-wide detection and characterization of positive selection in human populations. Nature 449: 913–918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K 1977. Pharmacology and function of the myoepithelial cell in the eccrine sweat gland. Experientia 33: 631–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Sato F 1990. Methods for studying eccrine sweat gland function in vivo and in vitro. Meth Enzymol 192: 583–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Sato F 1994. Interleukin-1α in human sweat is functionally active and derived from the eccrine sweat gland. Am J Physiol 266: R950–R959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Leidal R, Sato F 1987. Morphology and development of an apoeccrine sweat gland in human axillae. Am J Physiol 252: R166–R180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Kang WH, Saga K, Sato KT 1989a. Biology of sweat glands and their disorders. I. Normal sweat gland function. J Am Acad Dermatol 20: 537–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Kang WH, Saga K, Sato KT 1989b. Biology of sweat glands and their disorders: II. Disorders of sweat gland function. J Am Acad Dermatol 20: 713–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer RH, Abbott UK, Trelford JD 1972. Inductive interactions between human dermis and chick chorionic epithelium. Science 175: 527–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Nielsen K, Schmidt-Nielsen B, Jarnum SA, Houpt TR 1957. Body temperature of the camel and its relation to water economy. Am J Physiol 188: 103–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Ullrich R, Aebischer T, Hülsken J, Birchmeier W, Klemm U, Scheidereit C 2001. Requirement of NF-κB/Rel for the development of hair follicles and other epidermal appendices. Development 128: 3843–3853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackleton M, Vaillant F, Simpson KJ, Stingl J, Smyth GK, Asselin-Labat M-L, Wu L, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE 2006. Generation of a functional mammary gland from a single stem cell. Nature 439: 84–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shehadeh NH, Kligman AM 1963. The effect of topical antibacterial agents on the bacterial flora of the axilla. J Invest Dermatol 40: 61–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikiji T, Minami M, Inoue T, Hirose K, Oura H, Arase S 2003. Keratinocytes can differentiate into eccrine sweat ducts in vitro: Involvement of epidermal growth factor and fetal bovine serum. J Dermatol Sci 33: 141–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuster S, Johnson C 1969. The abnormality of sweat duct function in psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 81: 846–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snippert HJ, Haegebarth A, Kasper M, Jaks V, van Es JH, Barker N, van de Wetering M, van den Born M, Begthel H, Vries RG, et al. 2010. Lgr6 marks stem cells in the hair follicle that generate all cell lineages of the skin. Science 327: 1385–1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P 1999. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet 21: 70–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava AK, Durmowicz MC, Hartung AJ, Hudson J, Ouzts LV, Donovan DM, Cui CY, Schlessinger D 2001. Ectodysplasin-A1 is sufficient to rescue both hair growth and sweat glands in Tabby mice. Hum Mol Genet 10: 2973–2981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava AK, Pispa J, Hartung AJ, Du Y, Ezer S, Jenks T, Shimada T, Pekkanen M, Mikkola ML, Ko MS, et al. 1997. The Tabby phenotype is caused by mutation in a mouse homologue of the EDA gene that reveals novel mouse and human exons and encodes a protein (ectodysplasin-A) with collagenous domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci 94: 13069–13074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stingl J, Eirew P, Ricketson I, Shackleton M, Vaillant F, Choi D, Li HI, Eaves CJ 2006. Purification and unique properties of mammary epithelial stem cells. Nature 439: 993–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart ES, Moscona AA 1967. Embryonic morphogenesis: Role of fibrous lattice in the development of feathers and feather patterns. Science 157: 947–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun TT, Shih C, Green H 1979. Keratin cytoskeletons in epithelial cells of internal organs. Proc Natl Acad Sci 76: 2813–2817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takata M, Hashimoto K, Mehregan P, Lee MW, Yamamoto A, Mohri S, Ohara K, Takehara K 2000. Genetic changes in sweat gland carcinomas. J Cutan Pathol 27: 30–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoda Y, Sakurai A, Mitani Y, Nakashima M, Yoshiura K-I, Nakagawa H, Sakai Y, Ota I, Lezhava A, Hayashizaki Y, et al. 2009. Earwax, osmidrosis, and breast cancer: Why does one SNP (538G > A) in the human ABC transporter ABCC11 gene determine earwax type? FASEB J 23: 2001–2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker AS, Headon DJ, Schneider P, Ferguson BM, Overbeek P, Tschopp J, Sharpe PT 2000. Edar/Eda interactions regulate enamel knot formation in tooth morphogenesis. Development 127: 4691–4700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumbar T, Guasch G, Greco V, Blanpain C, Lowry WE, Rendl M, Fuchs E 2004. Defining the epithelial stem cell niche in skin. Science 303: 359–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Keymeulen A, Rocha AS, Ousset M, Beck B, Bouvencourt G, Rock J, Sharma N, Dekoninck S, Blanpain C 2011. Distinct stem cells contribute to mammary gland development and maintenance. Nature 479: 189–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voutilainen M, Lindfors PH, Lefebvre S, Ahtiainen L, Fliniaux I, Rysti E, Murtoniemi M, Schneider P, Schmidt-Ullrich R, Mikkola ML 2012. Ectodysplasin regulates hormone-independent mammary ductal morphogenesis via NF-κB. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109: 5744–5749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada M 1950. Sudorific action of adrenalin on the human sweat glands and determination of their excitability. Science 111: 376–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace ML, Longacre TA, Smoller BR 1995. Estrogen and progesterone receptors and anti-gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 (BRST-2) fail to distinguish metastatic breast carcinoma from eccrine neoplasms. Mod Pathol 8: 897–901 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh MJ, Smith AE 1993. Molecular mechanisms of CFTR chloride channel dysfunction in cystic fibrosis. Cell 73: 1251–1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel FG, Horn TD 1998. Nonneoplastic disorders of the eccrine glands. J Am Acad Dermatol 38: 1–17; quiz 18–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertkin MG, Bauer JJ 1976. Sweat gland carcinoma. Current concepts of surgical management. Arch Surg 111: 884–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wick MR, Ockner DM, Mills SE, Ritter JH, Swanson PE 1998. Homologous carcinomas of the breasts, skin, and salivary glands. A histologic and immunohistochemical comparison of ductal mammary carcinoma, ductal sweat gland carcinoma, and salivary duct carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 109: 75–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke K, Martin A, Terstegen L, Biel SS 2007. A short history of sweat gland biology. Int J Cosmet Sci 29: 169–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagawa S, Yokozeki H, Sato K 1986. Origin of periodic acid-Schiff-reactive glycoprotein in human eccrine sweat. J Appl Physiol 60: 1615–1622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Tomann P, Andl T, Gallant NM, Huelsken J, Jerchow B, Birchmeier W, Paus R, Piccolo S, Mikkola ML, et al. 2009. Reciprocal requirements for EDA/EDAR/NF-κB and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways in hair follicle induction. Dev Cell 17: 49–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler A, Jonason AS, Leffell DJ, Simon JA, Sharma HW, Kimmelman J, Remington L, Jacks T, Brash DE 1994. Sunburn and p53 in the onset of skin cancer. Nature 372: 773–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zonana J, Jones M, Browne D, Litt M, Kramer P, Becker HW, Brockdorff N, Rastan S, Davies KP, Clarke A 1992. High-resolution mapping of the X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (EDA) locus. Am J Hum Genet 51: 1036–1046 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]