Abstract

Background

Genetic counselling and testing for Lynch syndrome have recently been introduced in several South American countries, though yet not available in the public health care system.

Methods

We compiled data from publications and hereditary cancer registries to characterize the Lynch syndrome mutation spectrum in South America. In total, data from 267 families that fulfilled the Amsterdam criteria and/or the Bethesda guidelines from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Uruguay were included.

Results

Disease-predisposing mutations were identified in 37% of the families and affected MLH1 in 60% and MSH2 in 40%. Half of the mutations have not previously been reported and potential founder effects were identified in Brazil and in Colombia.

Conclusion

The South American Lynch syndrome mutation spectrum includes multiple new mutations, identifies potential founder effects and is useful for future development of genetic testing in this continent.

Keywords: Lynch syndrome, MLH1, MSH2, South America, Mutation

Background

Since the initial reports on disease-predisposing mutations in the mismatch-repair (MMR) genes MLH1 [MIM:120436], MSH2 [MIM:609309] and MSH6 [MIM:600678] in the early 1990’ies, a large number of studies have contributed to the establishment of the molecular map of Lynch syndrome with over 3,072 unique genetic MMR gene variants identified. These data are predominantly based on studies from North America, Europe and Asia. The mutations affect MLH1 in 42%, MSH2 in 33%, MSH6 in 18% and PMS2 in 8% [1]. Nonsense mutations, frameshift mutations and missense mutations predominate, whereas large genomic rearrangements and splice-site variants constitute <10% of the alterations [1].

The South American population is ethnically mixed from American Indian and European ancestors. In Uruguay and Argentina, European ancestry predominates. In Brazil, significant African and American Indians roots apply. In Chile, Colombia, Peru and Bolivia, Spanish colonist and American Indian ancestry influence the populations [2,3]. Mutation screening in South American families suspected of Lynch syndrome has identified disease-predisposing germline mutations in MLH1 and MSH2 in 16-45% of families that fulfill the Amsterdam criteria and/or the Bethesda guidelines [2-7]. Hereditary colorectal cancer registries have been established in Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay and Chile with the aim to collect and share data on the MMR gene mutation spectrum, identify potential founder mutations, interpret the role of unclassified genetic variants and to study cancer risks in the South American Lynch syndrome population. We used published data and unpublished register data to describe the mutation spectrum in South American Lynch syndrome families.

Methods

Ethics statement

All patients provided an informed consent for inclusion into the South American registers during genetic counseling sessions and is in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Patient selection

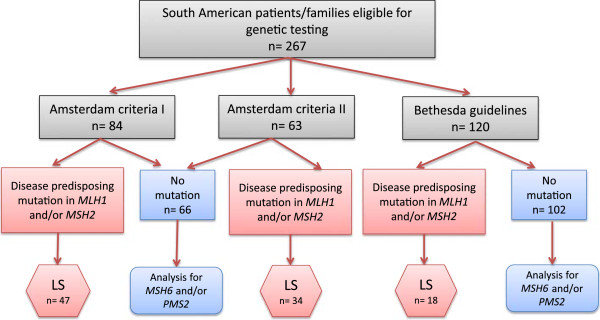

Families that fulfilled the Amsterdam criteria [8,9] and/or the Bethesda guidelines [10] were selected from the hereditary cancer registries at the Hospital Italiano (Buenos Aires, Argentina), the Hospital de las Fuerzas Armadas (Montevideo, Uruguay), the Clinica Los Condes (Santiago, Chile), the Barretos Cancer Hospital (Barretos, Brazil) and from two databases in Colombia and in Southeastern Brazil (Figure 1, Table 1) [2,3,5,11]. Patients were informed about their inclusion into the registries, which generally contained data on family history, age at onset and results of genetic testing.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of South American patients/families included in the study.

Table 1.

Summary of register data from MMR South American Lynch syndrome families

| South American Institutions | Total number of patients/families | MMR mutation carriers | % of MMR mutation carriers | Mean age at CRC diagnosis | Mean age at endometrial cancer diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital Italiano (Buenos Aires, Argentina) |

28 |

14 |

50.0 |

44.3 (SD 6.2) |

46.3 (SD 5.5) |

| Hospital de las Fuerzas Armadas (Montevideo, Uruguay) |

25 |

7 |

28.0 |

35.1 (SD 7.6) |

41.5 (SD 8.3) |

| Clinica Las Condesa (Santiago, Chile) |

50 |

20 |

40.0 |

35.7 (SD 10.7) |

41.1 (SD 8.8) |

| Barretos Cancer Hospitala (Barretos, Brazil) |

23 |

15 |

65.2 |

39.4 (SD 13.8) |

49.8 (SD 5.3) |

| Colombiac |

13 |

8 |

61.5 |

NA |

NA |

| Southeastern Brazilb |

128 |

35 |

27.3 |

42.3 (SD 11.4) |

48.8 (SD 2.4) |

| Total | 267 | 99 | 37.1 |

Disease-predisposing mutations

Methods to assess MMR status, e.g. microsatellite instability analysis and MMR protein staining, varied between the countries and were excluded from the present study since these data were incomplete. Molecular diagnosis was generally based on direct sequencing of MLH1 and MSH2. Chilean and Brazilian families were also analyzed for large genomic rearrangements using the multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) method (performed using the SALSA kit P003, MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, Netherlands).

Mutation nomenclature

Mutation nomenclature was in accordance with the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) guidelines [12]. Mutations in the MLH1 or MSH2 genes were considered deleterious if they: a) were classified as pathogenic in LOVD database; b) introduced a premature stop codon in the protein sequence (nonsense or frameshift mutation); c) occurred at donor or acceptor splice sites; or d) represented whole-exon deletions or duplications. All identified mutations were correlated to the MMR Gene Unclassified Variants Database (http://www.mmruv.info), the Mismatch Repair Genes Variant Database (http://www.med.mun.ca/mmrvariants/), the French MMR network (http://www.umd.be/MMR.html) and the International Society for Gastrointestinal Hereditary Tumors (InSIGHT) (http://www.insight-group.org).

Variants of uncertain significance

To establish the pathogenicity of variants of uncertain significance, web-based programs, i.e. Polyphen, MAPP-MMR, SIFT, P-mut and PON-MMR were applied to predict the effect of an amino acid substitution based on protein structural change and/or evolutionary conservation [13-17].

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics 20 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

In total, 110 families harbored MMR gene variants, of which 99 were classified as Lynch syndrome predisposing and 11 were regarded as variants of uncertain significance. Mutations in MLH1 and MSH2 were identified in 37% (range 27-65% in the different countries/registries) of the families that fulfilled the Amsterdam criteria and/or Bethesda guidelines (Table 1). When the Amsterdam criteria were considered, the mutation detection rate was 55% (81/147), whereas 15% families that fulfilled the Bethesda guidelines had disease-predisposing mutations. The mean age at diagnosis was 35–44 years for colorectal cancer and 41–49 years for endometrial cancer in the different registries (Table 1). Pedigree information was available from 54 families and showed that among the Lynch syndrome-associated tumors, 65% were colorectal cancers (of which 43% were located in the right side of the colon), 22% endometrial cancers and 13% constituted other Lynch syndrome-associated cancer types.

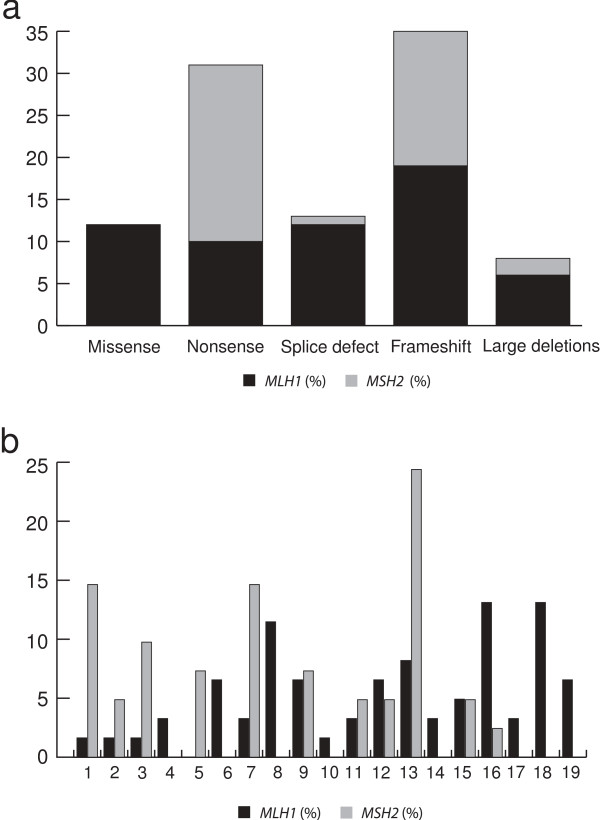

Of the 99 disease-predisposing MMR gene mutations, 60% affected MLH1 and 40% affected MSH2 (Table 2). Frameshift and nonsense mutations were the most common alterations (36% and 31%, respectively), followed by splice site mutations (13%), missense mutations (12%) and large deletions (8%) (Figure 2a). Though the mutations were spread over the genes, hot-spot regions included exons 16 and 18 in MLH1 (13% of the mutations each) and exon 13 in MSH2 (24% of the mutations each) (Figure 2b).

Table 2.

Spectrum of alterations in South American Lynch syndrome families

| Gene | Nucleotide | Consequence | Exon | Reported as | Country | Number of families | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

MLH1 |

c.1-?_116 + ?del |

p.M1_C39 > FfsX13 |

1 |

Causal |

Chile |

2 |

InSIGHT |

| c.199G > A |

p.G67R |

2 |

Causal |

Argentina |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.211G > T |

p.E71X |

3 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.289 T > G |

p.Y97D |

3 |

VUS |

Uruguay |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| C.336 T > A |

p.H112Q |

4 |

VUS |

Argentina |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.350C > T |

p.T117M |

4 |

Causal |

Uruguay |

2 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.421C > G |

p.P141A |

5 |

VUS |

Colombia |

1 |

Giraldo et al. 2005 [2] |

|

| c.503dupA |

p.N168KfsX4 |

6 |

Causal |

Chile |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.503delAa |

p.N168IfsX34 |

6 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

Not previously described |

|

| c.545 + 3A > G |

|

6 |

Causal |

Brazil |

2 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.588 + 2 T > Aa |

|

7 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

Valentin et al. 2011 [3] |

|

| c.588 + 5G > C |

|

7 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.665delA |

p.N222MfsX7 |

8 |

Causal |

Uruguay |

2 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.676C > T |

p.R226X |

8 |

Causal |

Argentina |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.677G > A |

p.R226Q |

8 |

Causal |

Argentina, Brazil |

3 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.677 + 5G > A |

|

8 |

Likely causal |

Chile |

1 |

French MMR network |

|

| c.779 T > G |

p.L260R |

9 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.790 + 1G > A |

|

9 |

Causal |

Chile, Colombia |

3 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.791-6_793delgtttagATCa |

|

10 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

Valentin et al. 2011 [3] |

|

| c.794G > C |

p.R265P |

10 |

VUS |

Chile |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.901C > T |

p.Q301X |

11 |

Causal |

Chile |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1013A > Ga |

p.N338S |

11 |

VUS |

Brazil |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1038 + 1G > Ta |

p.Y347FfsX13 |

11 |

Causal |

Chile |

1 |

Wielandt et al. 2012 |

|

| c.1039-8T_1558?896Tdupa |

p.520Vfs564X |

12 to 13 |

Causal |

Colombia |

2 |

Alonso-Espinaco et al. 2011 [11] |

|

| c.1276C > T |

p.Q426X |

12 |

Causal |

Brazil |

3 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1459C > T |

p.R487X |

13 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1499_1501delTCAa |

p.I500del |

13 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

Rossi et al. 2002 [5] |

|

| c.1558 + 1G > T |

|

13 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1558 + 14G > A |

|

13 |

VUS |

Colombia |

2 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1559-2A > C |

|

13 |

Causal |

Chile |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1559-?_1731 + ?del |

p.V520_S577 > GfsX7b |

14 -15 |

Causal |

Chile |

1 |

Wielandt et al. 2012 |

|

| c.1639_1643dup TTATAa |

p.L549YfsX44 |

14 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

Valentin et al. 2011 [3] |

|

| c.1690_1693delCTCA |

p.L564FfsX26 |

15 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1724G > A |

p.R575K |

15 |

VUS |

Argentina |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1731 + 3A > Ta |

Skipping exon 15 |

15 |

Causal |

Chile |

1 |

Alvarez et al. 2010 [6] |

|

| c.1846delAAG |

p.K616del |

16 |

Causal |

Argentina |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1852_1853delinsGC |

p.K618A |

16 |

Causal |

Argentina |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1852_1854 delAAG |

p.K618del |

16 |

Causal |

Argentina |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1853A > C |

p.K618T |

16 |

VUS |

Brazil |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1853delAinsTTCTTa |

p.K618IfsX4 |

16 |

Causal |

Brazil |

2 |

Valentin et al. 2011 [3] |

|

| c.1856delGa |

|

16 |

Causal |

Colombia |

2 |

Giraldo et al. 2005 [2] |

|

| c.1890dupa |

p.D631fsX1 |

16 |

Causal |

Argentina |

1 |

Valentin et al. 2011 [3] |

|

| c.1897-?_1989 + ?dela |

|

17-19 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

Not previously described |

|

| c.1918C > T |

p.P640T |

17 |

VUS |

Colombia |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1975C > T |

p.R659X |

17 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1998G > A |

p.W666X |

18 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

Rossi et al. 2012 [5] |

|

| c.2027 T > C |

p.L676P |

18 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.2041G > A |

p.A681T |

18 |

Likely causal |

Chile, Brazil, Colombia |

4 |

French MMR network |

|

| c.2092_2093delTC |

p.S698RfsX5 |

18 |

Causal |

Chile |

1 |

Alvarez et al. 2010 [6] |

|

| c.2224C > Ta |

p.Q742X |

19 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

Valentin et al. 2011 [3] |

|

| c.2252_2253dupAA |

p.V752KfsX26 |

19 |

VUS |

Brazil |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.2104-?_2271 + ?delb |

p.S702_X757del |

19 |

Causal |

Chile |

2 |

Wielandt et al. 2012 |

|

| MSH2 | c.71delAa |

p.Q24fs |

1 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

Not previously described |

| c.166G > Ta |

p.E56X |

1 |

Causal |

Argentina |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.174dupCa |

|

1 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

Not previously described |

|

| c.175dupCa |

p.K59QfsX23 |

1 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

Valentin et al. 2011 [3] |

|

| c.181C > Ta |

p.Q61X |

1 |

Causal |

Uruguay |

1 |

Sarroca et al. 2003 |

|

| c.187delG |

p.V63fsX1 |

1 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.289C > T |

p.Q97X |

2 |

Causal |

Argentina |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.212-?_366 + ?del |

p.A72_K122 > FfsX9 |

2 |

Causal |

Chile |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.388_389delCA |

p.Q130VfsX2 |

3 |

Causal |

Brazil, Argentina |

2 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.530_531delAAa |

p.E177fsX3 |

3 |

Causal |

Uruguay |

1 |

Sarroca et al. 2003 |

|

| c.596delTGa |

|

3 |

Causal |

Colombia |

1 |

Giraldo et al. 2005 [2] |

|

| c.862C > T |

p.Q287X |

5 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.897 T > G |

p.Y299X |

5 |

Causal |

Chile |

1 |

Wielandt et al. 2012 |

|

| c.942 + 3 A > T |

|

5 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1077-?_1276 + ?del |

p.L360KfsX16 |

7 |

Causal |

Argentina |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1147C > T |

p.R382X |

7 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1215C > A |

p.Y405X |

7 |

Causal |

Chile |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1216C > T |

p.R406X |

7 |

Causal |

Uruguay |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1249delG |

p.V417LfsX21 |

7 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1255C > T |

p.Q419X |

7 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1444A > Ta |

p.R482X |

9 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

Valentin et al. 2011 [3] |

|

| c.1447G > T |

p.E483X |

9 |

Causal |

Brazil |

2 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.1667delTa |

p.L556X |

11 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

Valentin et al. 2011 [3] |

|

| c.1667_1668insAa |

p.T557DfsX5 |

11 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

Rossi et al. 2002 [5] |

|

| c.1910delCa |

p.R638GfsX47 |

12 |

Causal |

Argentina |

1 |

Vaccaro et al. 2007 |

|

| c.1967_1970dupACTTa |

p.F657LfsX3 |

12 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

Valentin et al. 2011 [3] |

|

| c.2038C > T |

p.R680X |

13 |

Causal |

Chile |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.2046_2047delTGa |

p.V684Dfs*14 |

13 |

Causal |

Argentina |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.2131C > T |

p.R711X |

13 |

Causal |

Brazil |

1 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.2152C > T |

p.Q718X |

13 |

Causal |

Brazil |

6 |

InSIGHT |

|

| c.2185_2192del7insCCCTa |

p.M729_E731delinsP729_X730 |

13 |

Causal |

Chile |

1 |

Alvarez et al. 2010 [6] |

|

| c.2187G > Ta |

p.M729I |

13 |

VUS |

Brazil |

1 |

Valentin et al. 2011 [3] |

|

| c.2525_2526delAGa |

p.E842VfsX3 |

15 |

Causal |

Brazil |

2 |

Valentin et al. 2011 [3] |

|

| c.2785C > Ta | p.R929X | 16 | Causal | Brazil | 1 | Valentin et al. 2011 [3] |

aFirst reported, VUS variants of unclassified significance, MLH1 (MIM#120436), MSH2 (MIM#609309),bpathogenecity demonstration ongoing.

Figure 2.

Spectrum of pathogenic mutations in MLH1 and MSH2 genes a) Types of pathogenic germline mutations; b) Distribution along all exons of the MMR genes.

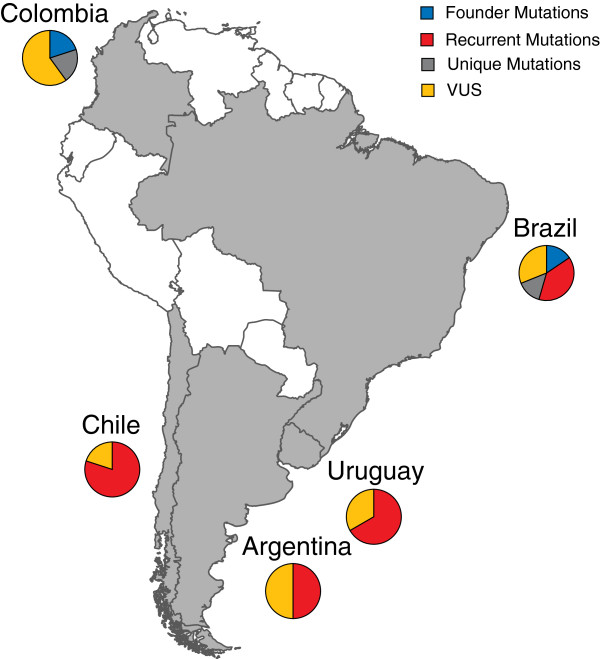

In total, 10 mutations identified in at least two South American families were classified as recurrent. Among these, the MSH2 c.2152C > T identified in Brazil represents an internationally hot-spot. Three founder mutations were identified in five South American families. The MLH1 c.545 + 3A > G and the MSH2 c.942 + 3A > T have been identified as founder mutations in Italy and in Newfoundland and were also identified in Brazilian families [3]. The MLH1 c.1039-8T_1558 + 896Tdup has been suggested to represent a founder mutation in Colombia [2,11]. Mutations that were unique and herein first reported in more than one family included the MLH1 c.1853delAinsTTCTT in Brazil, the MLH1 c.1856delG in Colombia and the MSH2 c.25252_2526delAG in Brazil (Table 2) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Map of South America showing the countries where Lynch syndrome families with the founder, recurrent, unique mutations and variants of unclassified significance (VUS) have been identified. The figure depicts the countries participating in the study (gray). The pie chart represents in percentage the recurrent mutations, unique mutations, founder mutations and VUS identified in the South American families. Brazil is characterized by 16% of the founder mutations, 39% of the recurrent mutations, 14% of the unique mutations and 31% of the VUS, while Colombia by 20% of the founder mutations, 20% of the unique mutations and 60% of the VUS. Chile, Argentina and Uruguay are characterized by 80%, 50% and 67% of the recurrent mutations and 20%, 50% and 33% of the VUS, respectively.

In total, 11 variants of unclassified significance were identified in individuals from Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Brazil and Colombia (Table 3) [2,3]. In silico analysis suggested that the MLH1 c.289 T > G, the MLH1c.794G > C and the MLH1c.1918C > T were likely disease-predisposing (Table 3).

Table 3.

Variants of unclassified significance and in silico prediction in South American Lynch syndrome families

| Country | Gene | Nucleotide | Consequence | Exon |

Polyphen |

SIFT |

MAP_MMR |

P-mut |

PON-MMR |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | Classification | Score | Classification | Score | Classification | Score | Classification | Score | Classification | |||||

| Uruguay |

MLH1 |

c.289 T > G |

p.Y97D |

3 |

0.999 |

Probably damaging |

0 |

Damaging |

10.51 |

Damaging |

0.7266 |

Pathological |

0.83 |

Pathogenic |

| Argentina |

MLH1 |

c.336 T > A |

p.H112Q |

4 |

1 |

Probably damaging |

0.03 |

Damaging |

2.430 |

Neutral |

NA |

NA |

0.61 |

VUS |

| Colombia |

MLH1 |

c.421C > G |

p.P141A |

5 |

0.329 |

Benign |

0.05 |

Damaging |

3.15 |

Borderline deleterious |

0.4928 |

Neutral |

0.48 |

VUS |

| Chile |

MLH1 |

c.794G > C |

p.R265P |

10 |

1 |

Probably damaging |

0 |

Damaging |

38.09 |

Damaging |

0.7623 |

Pathological |

0.83 |

Pathogenic |

| Brazil |

MLH1 |

c.1013A > G |

p.N338S |

11 |

0.506 |

Possibly Damaging |

0.05 |

Damaging |

2.78 |

Neutral |

0.2551 |

Neutral |

0.38 |

VUS |

| Colombia |

MLH1 |

c.1558 + 14G > A |

|

13 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Argentina |

MLH1 |

c.1724G > A |

p.R575K |

15 |

0.001 |

Benign |

0.40 |

Tolerated |

1.490 |

Neutral |

NA |

NA |

0.15 |

Neutral |

| Brazil |

MLH1 |

c.1853A > C |

p.K618T |

16 |

0.997 |

Probably damaging |

0.02 |

Damaging |

5.11 |

Damaging |

0.7802 |

Pathological |

0.67 |

VUS |

| Colombia |

MLH1 |

c.1918C > T |

p.P640T |

17 |

1 |

Probably damaging |

0 |

Damaging |

17.77 |

Damaging |

0.6534 |

Pathological |

0.83 |

Pathogenic |

| Brazil |

MLH1 |

c.2252_2253dupAA |

p.V752Kfs*26 |

19 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Brazil | MSH2 | c.2187G > T | p.M729I | 13 | 2.293 | Probably damaging | 0 | Damaging | 21.99 | Damaging | 0.1988 | Neutral | 0.71 | VUS |

MLH1 (MIM#120436), MSH2 (MIM#609309), NA: not applicable, VUS: variants of unclassified significance, If SIFT score <0.05 then the aminoacid (AA) substitution is predicted to affect protein function, if PolyPhen score >0.5 then the AA substitution is predicted to affect protein function, if MAPP-MMR score >4.55 then the AA substitution is predicted to affect protein function, If P-mut score > 0.5, the AA substitution is classified as pathological, if PON-MMR score >0.7615, the AA substitution is classified as pathogenic.

Discussion

In South America, disease-predisposing mutations linked to Lynch syndrome have been identified in 99 families, which corresponds to 37% of the families that fulfilled the Amsterdam criteria and/or Bethesda guidelines and underwent genetic testing. The mutation rate is high compared to prevalence rates of 28% for MLH1 and 18% for MSH2 in the Asian population, 31% and 20% in a multi-ethnic American population and 26% and 19% in European/Australian populations [18]. The mutation spectrum is predominated by MLH1 (60%) and MSH2 (40%) mutations [3,19-22], but the seemingly larger contribution than the 42% and 33% reported in the InSIGHT database could reflect failure to test for MSH6 and PMS2 mutations in most South American studies [1]. Referral bias in populations that have more recently been screened for mutations represents a potential limitation, but the strong contribution from MLH1 and MSH2 could also reflect population structure [2,4,5,7]. Frameshift mutations and nonsense mutations were the most common types of mutations, which are in agreement with findings from other populations [1,23-26], with hotspots in exons 16 and 18 of MLH1 and in exon 13 of MSH2 (Figure 2b). Exon 16 and 18 in MLH1 has been identified as a genetic hot spot also in other populations with 26% of the MLH1 mutations reported herein [3,18]. The frequent mutations in MSH2 exon 13 may be linked to the c.2152C>, which was first identified in Portuguese Lynch syndrome families. This alteration accounted for 35% (6/17) of the MSH2 mutations in the Brazilian population, which is in line with the Portuguese migration to Brazil [3,27].

Founder mutations have been identified in several populations where they significantly contribute to disease predisposition and thereby allow for directed genetic testing [28]. Two of the mutations identified in South American Lynch syndrome families have been suggested to constitute potential founder mutations in other populations, e.g. the Italian MLH1 c.545 + 3A > G and the Newfoundland MSH2 c.942 + 3A > T [3]. The Spanish founder mutations MLH1 c.306 + 5G > A and c.1865 T > A and MSH2 c.2635-3 T > C; c2635-5C > T; c.2063 T > G were, however, not observed in South American Lynch syndrome families [27-30]. In Colombia, the MSH2 c.1039-8T_1558 + 896Tdup was suggested to represent a founder mutation [2,11]. The Colombian population has a mixed ancestry with a strong influence from Spanish colonists and thereby genetically differs from previously studied populations [2,6].

Conclusions

In conclusion, disease-predisposing mutations in MLH1 and MSH2 have been identified in a relatively large proportion of the South American families suspected of Lynch syndrome that have been tested. Genetic hot-spot regions, internationally recognized founder mutations and potential South American founder mutation have been recognized, which is of relevance for genetic counseling and testing that are increasingly available in South America.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MDV, MN, BMR participated in the conception and design of the study. All authors participated in the acquisition of data, or analysis, interpretation of data and have been involved in drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Mev Dominguez-Valentin, Email: mev_dv@yahoo.com.

Mef Nilbert, Email: mef.nilbert@med.lu.se.

Patrik Wernhoff, Email: patrik.wernhoff@med.lu.se.

Francisco López-Köstner, Email: flopez@med.puc.cl.

Carlos Vaccaro, Email: carlos.vaccaro@hospitalitaliano.org.ar.

Carlos Sarroca, Email: paleta@adinet.com.uy.

Edenir Ines Palmero, Email: edenip@yahoo.com.br.

Alejandro Giraldo, Email: agiraldori@unal.edu.co.

Patricia Ashton-Prolla, Email: pprolla@portoweb.com.br.

Karin Alvarez, Email: kalvarez@clinicalascondes.cl.

Alejandra Ferro, Email: alejandra.ferro@hospitalitaliano.org.ar.

Florencia Neffa, Email: floneffa@gmail.com.

Junea Caris, Email: juneacaris@usp.br.

Dirce M Carraro, Email: dircecarraro@hotmail.com.

Benedito M Rossi, Email: bmrossi@me.com.

References

- Plazzer JP, Sijmons RH, Woods MO, Peltomaki P, Thompson B, DenDunnen JT, Macrae F. The InSiGHT database: utilizing 100 years of insights into Lynch Syndrome. Fam Cancer. 2013;11:175–180. doi: 10.1007/s10689-013-9616-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo A, Gomez A, Salguero G, Garcia H, Aristizabal F, Gutierrez O, Angel LA, Padron J, Martinez C, Martinez H. et al. MLH1 and MSH2 mutations in Colombian families with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome)–description of four novel mutations. Fam Cancer. 2005;11:285–290. doi: 10.1007/s10689-005-4523-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentin MD, da Silva FC, dos Santos EM, Lisboa BG, de Oliveira LP, Ferreira Fde O, Gomy I, Nakagawa WT, Aguiar Junior S, Redal M. et al. Characterization of germline mutations of MLH1 and MSH2 in unrelated south American suspected Lynch syndrome individuals. Fam Cancer. 2011;11:641–647. doi: 10.1007/s10689-011-9461-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarroca C, Valle AD, Fresco R, Renkonen E, Peltomaki P, Lynch H. Frequency of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer among Uruguayan patients with colorectal cancer. Clin Gen. 2005;11:80–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2005.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi BM, Lopes A, Oliveira Ferreira F, Nakagawa WT, Napoli Ferreira CC, Casali Da Rocha JC, Simpson CC, Simpson AJ. hMLH1 and hMSH2 gene mutation in Brazilian families with suspected hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;11:555–561. doi: 10.1007/BF02573891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez K, Hurtado C, Hevia MA, Wielandt AM, de la Fuente M, Church J, Carvallo P, Lopez-Kostner F. Spectrum of MLH1 and MSH2 mutations in Chilean families with suspected Lynch syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;11:450–459. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181d0c114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccaro CA, Bonadeo F, Roverano AV, Peltomaki P, Bala S, Renkonen E, Redal MA, Mocetti E, Mullen E, Ojea-Quintana G. et al. Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch Syndrome) in Argentina: report from a referral hospital register. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;11:1604–1611. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9037-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasen HF, Mecklin JP, Khan PM, Lynch HT. The International Collaborative Group on Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer (ICG-HNPCC) Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;11:424–425. doi: 10.1007/BF02053699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasen HF, Watson P, Mecklin JP, Lynch HT. New clinical criteria for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC, Lynch syndrome) proposed by the International Collaborative group on HNPCC. Gastroenterology. 1999;11:1453–1456. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70510-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Boland CR, Hamilton SR. et al. A national cancer institute workshop on hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome: meeting highlights and Bethesda guidelines. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;11:1758–1762. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.23.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Espinaco V, Giraldez MD, Trujillo C, van der Klift H, Munoz J, Balaguer F, Ocana T, Madrigal I, Jones AM, Echeverry MM. et al. Novel MLH1 duplication identified in Colombian families with Lynch syndrome. Genet Med. 2011;11:155–160. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318202e10b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- denDunnen JT, Antonarakis SE. Mutation nomenclature extensions and suggestions to describe complex mutations: a discussion. Hum Mutat. 2000;11:7–12. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200001)15:1<7::AID-HUMU4>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;11:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao EC, Velasquez JL, Witherspoon MS, Rozek LS, Peel D, Ng P, Gruber SB, Watson P, Rennert G, Anton-Culver H. et al. Accurate classification of MLH1/MSH2 missense variants with multivariate analysis of protein polymorphisms-mismatch repair (MAPP-MMR) Hum Mutat. 2008;11:852–860. doi: 10.1002/humu.20735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc. 2009;11:1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-Costa C, Orozco M, de la Cruz X. Sequence-based prediction of pathological mutations. Proteins. 2004;11:811–819. doi: 10.1002/prot.20252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali H, Olatubosun A, Vihinen M. Classification of mismatch repair gene missense variants with PON-MMR. Hum Mutat. 2012;11:642–650. doi: 10.1002/humu.22038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Hu F, Wang F, Cui B, Dong X, Zhang W, Lin C, Li X, Wang D, Zhao Y. Prevalence of pathological germline mutations of hMLH1 and hMSH2 genes in colorectal cancer. PloS One. 2013;11:e51240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez MV, Bastos EP, Santos EM, Oliveira LP, Ferreira FO, Carraro DM, Rossi BM. Two new MLH1 germline mutations in Brazilian Lynch syndrome families. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;11:1263–1264. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0515-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva FC, de Oliveira LP, Santos EM, Nakagawa WT, Aguiar Junior S, Valentin MD, Rossi BM, de Oliveira Ferreira F. Frequency of extracolonic tumors in Brazilian families with Lynch syndrome: analysis of a hereditary colorectal cancer institutional registry. Fam Cancer. 2010;11:563–570. doi: 10.1007/s10689-010-9373-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro Santos EM, Valentin MD, Carneiro F, de Oliveira LP, de Oliveira FF, Junior SA, Nakagawa WT, Gomy I, de FariaFerraz VE, da Silva Junior WA. et al. Predictive models for mutations in mismatch repair genes: implication for genetic counseling in developing countries. BMC Cancer. 2012;11:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentin MD, Da Silva FC, Santos EM, Da Silva SD, De Oliveira FF, Aguiar Junior S, Gomy I, Vaccaro C, Redal MA, Della Valle A. et al. Evaluation of MLH1 I219V polymorphism in unrelated South American individuals suspected of having Lynch syndrome. Anticancer Res. 2012;11:4347–4351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltomaki P, Vasen HF. The International Collaborative Group on Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer. Mutations predisposing to hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer: database and results of a collaborative study. Gastroenterology. 1997;11:1146–1158. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9322509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apessos A, Mihalatos M, Danielidis I, Kallimanis G, Agnantis NJ, Triantafillidis JK, Fountzilas G, Kosmidis PA, Razis E, Georgoulias VA, Nasioulas G. hMSH2 is the most commonly mutated MMR gene in a cohort of Greek HNPCC patients. Br J Cancer. 2005;11:396–404. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjoblom T, Jones S, Wood LD, Parsons DW, Lin J, Barber TD, Mandelker D, Leary RJ, Ptak J, Silliman N. et al. The consensus coding sequences of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2006;11:268–274. doi: 10.1126/science.1133427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilbert M, Wikman FP, Hansen TV, Krarup HB, Orntoft TF, Nielsen FC, Sunde L, Gerdes AM, Cruger D, Timshel S. et al. Major contribution from recurrent alterations and MSH6 mutations in the Danish Lynch syndrome population. Fam Cancer. 2009;11:75–83. doi: 10.1007/s10689-008-9199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isidro G, Veiga I, Matos P, Almeida S, Bizarro S, Marshall B, Baptista M, Leite J, Regateiro F, Soares J. et al. Four novel MSH2 / MLH1 gene mutations in portuguese HNPCC families. Hum Mutat. 2000;11:116. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200001)15:1<116::AID-HUMU24>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borras E, Pineda M, Blanco I, Jewett EM, Wang F, Teule A, Caldes T, Urioste M, Martinez-Bouzas C, Brunet J. et al. MLH1 founder mutations with moderate penetrance in Spanish Lynch syndrome families. Cancer Res. 2010;11:7379–7391. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez M, Castellvi-Bel S, Pineda M, de Cid R, Munoz J, Gonzalez S, Teule A, Balaguer F, Ramon y Cajal T, Rene JM. et al. Founder effect of a pathogenic MSH2 mutation identified in Spanish families with Lynch syndrome. Clin Gen. 2010;11:186–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Arana V, Barrios Y, Fernandez-Peralta A, Herrera M, Chinea N, Lorenzo N, Jimenez A, Martin-Lopez JV, Gonzalez-Hermoso F, Salido E, Gonzalez-Aguilera JJ. New founding mutation in MSH2 associated with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome on the Island of Tenerife. Cancer Lett. 2006;11:268–273. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]