Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effect of home visits by Community Health Workers (CHW) on maternal and infant well-being from pregnancy through the first six months of life for women living with HIV (WLH) and all neighbourhood mothers.

Design and Methods

In a cluster randomised controlled trial in Cape Town townships, neighbourhoods were randomised within matched pairs to either: 1) Standard Care, comprehensive healthcare at clinics (SC; n=12 neighbourhoods; n=169 WLH; n=594 total mothers), or 2) Philani Intervention Program, home visits by CHW in addition to SC (PIP; n=12 neighbourhoods; n=185 WLH; n=644 total mothers). Participants were assessed during pregnancy (2% refusal) and reassessed at one week (92%) and six months (88%) post-birth. We analysed PIP’s effect on 28 measures of maternal and infant well-being among WLH and among all mothers using random effects regression models. For each group, PIP’s overall effectiveness was evaluated using a binomial test for correlated outcomes.

Results

Significant overall benefits were found in PIP compared to SC among WLH and among all participants. Secondarily, compared to SC, PIP WLH were more likely to complete tasks to prevent vertical transmission, use one feeding method for 6 months, avoid birth-related medical complications, and have infants with healthy height-for-age measurements. Among all mothers, compared to SC, PIP mothers were more likely to use condoms consistently, breastfeed exclusively for 6 months, and have infants with healthy height-for-age measurements.

Conclusions

PIP is a model for countries facing significant reductions in HIV funding whose families face multiple health risks.

Keywords: HIV, maternal health, perinatal health

Introduction

For the last 10 years, evidence has been mounting on the importance of integrating HIV care with care of other health risks [1]. In Low and Middle Income Countries (LMIC), including South Africa, children’s health is compromised not only by HIV, but by the cumulative impact of poverty and related deficits from other infectious diseases, malnutrition, and maternal behaviours [2–3]. Yet, community health workers (CHWs) typically target single outcomes, such as HIV testing [4], tuberculosis (TB) adherence [5], securing a child grant [6], or maternal depression [7]. In some LMIC, two to three different CHWs visit a household, each targeting a different health risk, but also replicating some components of the intervention. HIV-identified CHW are also more likely to be rejected, given the stigma surrounding HIV [8].

In contrast, we trained CHWs to address multiple heath behaviours. A home visiting intervention strategy for new mothers has repeatedly been demonstrated efficacious in the United States with significant short- and long-term outcomes when delivered by nurses [9–12]. The current global shortage of healthcare personnel in LMIC requires task-shifting from professionals to CHWs [13–14]. This study, set in Cape Town townships, evaluates the ability of home visits by CHWs to improve the well-being of mothers and infants from pregnancy to the first six months of life for women living with HIV (WLH) and for all mothers. CHWs were trained in foundational skills to support behavioural change [15], specifically for HIV, alcohol use, infant malnutrition, and general maternal and child health.

We hypothesized that, compared to the Standard Care (SC), WLH and all mothers in the Philani Intervention Program (PIP) would have improved maternal and child health and well-being in five domains: (1) adherence to HIV-related preventive acts (for WLH, including the tasks to Prevent Mother-to-Child Transmission [PMTCT]), (2) child health and nutrition (including alcohol use during pregnancy and breastfeeding), (3) healthcare and monitoring, (4) mental health, and (5) social support [16].

Methods

The Institutional Review Boards of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Stellenbosch University, and Emory University approved the study [16].

Standard Care (SC) and Philani Intervention Program (PIP) conditions

SC

The SC condition consisted of access to healthcare at government clinics and hospitals, including rapid HIV testing and receipt of results. WLH were routinely offered HIV care, including testing for CD4; antiretroviral medication (ARV) for WLH with low CD4 counts; maternal azidothymidine (AZT) from the 28th week of pregnancy and during delivery; nevirapine (NVP) for the mother during delivery and for the infant within 24 hours of birth; and infant AZT, formula tins, cotrimoxazole, and HIV PCR testing post-birth.

PIP

The PIP condition received antenatal and postnatal home visits by CHW in addition to the clinic-based care that is SC. CHW were selected to have good social/communication skills, problem-solving skills, and thriving children (positive deviants). CHW were trained for one month using an intervention manual, role-playing, and watching videotapes of common challenging situations that CHW might face during home visits. All CHW were trained in: 1) foundational skills in behaviour change; 2) application of key health information about HIV, alcohol use, malnutrition, and general maternal and child health; and 3) coping with their own life challenges. CHWs worked 20 hours weekly, and were paid R1250 a month (about 150 USD).

In accordance with standard procedures for an effectiveness trial, PIP was mounted by the local Philani Maternal, Child Health and Nutrition Program, a community-based organization. CHWs systematically visited every home in their assigned neighbourhood, identified pregnant mothers, carried a scale to weigh infants, plotted weight on growth charts to identify underweight children, and transcribed outcomes from the government-issued Road-to-Health card. The antenatal messages concerned: 1) good maternal nutrition and preparing for breastfeeding; 2) regular antenatal clinic attendance and danger signs; 3) HIV testing, PMTCT tasks and partner prevention strategies; and 4) stopping alcohol use [17]. The postnatal messages were: 1) breastfeeding and growth monitoring; 2) medical adherence (immunisations, prevention for HIV-exposed children); 3) infant bonding; and 4) securing the child grant. The home visits were monitored in two ways: 1) CHW handwritten notes; and 2) CHWs carried mobile phones that noted visit time, length, content covered, and perceived impact.

On average, CHWs made 6 antenatal visits (range, 1–27) and 5 postnatal visits between birth and 2 months post-birth (range, 1–12) per participant. Sessions averaged 31 minutes (SD=20). Supervisors monitored implementation by reviewing charts and visit documentation on mobile phones, making random site visits once every two weeks, and providing monthly CHW in-service trainings.

Procedures

Neighbourhood matching and randomisation

Household randomisation would have increased the intervention’s stigma and resulted in substantial contamination; therefore, we randomised by neighbourhood. Similar neighbourhoods (N=40) were selected based on analysis of aerial photos, field observations, brief street-intercept surveys, and systematic counting of the number of alcohol bars, informal shops, clinics, child care centres, schools, and formal and informal houses per neighbourhood. Based on these data, we identified 13 matched pairs of similarly-sized neighbourhoods (450–600 households) with formal and informal housing, that were within five kilometres of health clinics; had five to seven alcohol bars; were non-contiguous or separated by natural barriers; had similar numbers of child care centres, informal shops, and schools; and had households with similar length of residence. In a cluster randomised controlled design, the UCLA team randomised neighbourhoods within matched pairs to PIP or SC using simple randomisation. One matched pair was eliminated after 6 months of recruitment due to low numbers of pregnant women (total n=10 pregnant women), leaving 24 study neighbourhoods [16].

Sample size calculations were conducted to determine the minimum number of pregnant women to be recruited per neighbourhood to achieve 80% power to detect a standardized effect size of 0.40 between intervention conditions among WLH and among all women [16].

Participants

Recruitment and retention

Three separate teams conducted the study to reduce any potential bias in data collection (Stellenbosch), intervention implementation (the Philani Program), and analyses (UCLA). From May 2009 to September 2010, the Stellenbosch team hired local township mothers to recruit pregnant women who were at least 18 years old, living within the target neighbourhood, and able to give informed consent. Each recruiter worked in one PIP and one SC neighbourhood to ensure that recruiter competence was similar across conditions. Pregnant women were recruited at an average 26 weeks of pregnancy (range, 3–40 weeks); only 2% of women refused participation. Initially, however, we identified 22% fewer pregnant women in SC. By redeploying recruiters, we identified an additional 94 women in 10 of the 12 SC neighbourhoods who were pregnant during the recruitment period (median of 7 late-entry participants per neighbourhood; range, 3–24). These women were enrolled post-birth when their infants were a mean age of 9 months old (range, 1–18 months). The final sample (n=1238) comprised a median of 51 pregnant women per neighbourhood (range, 23–72).

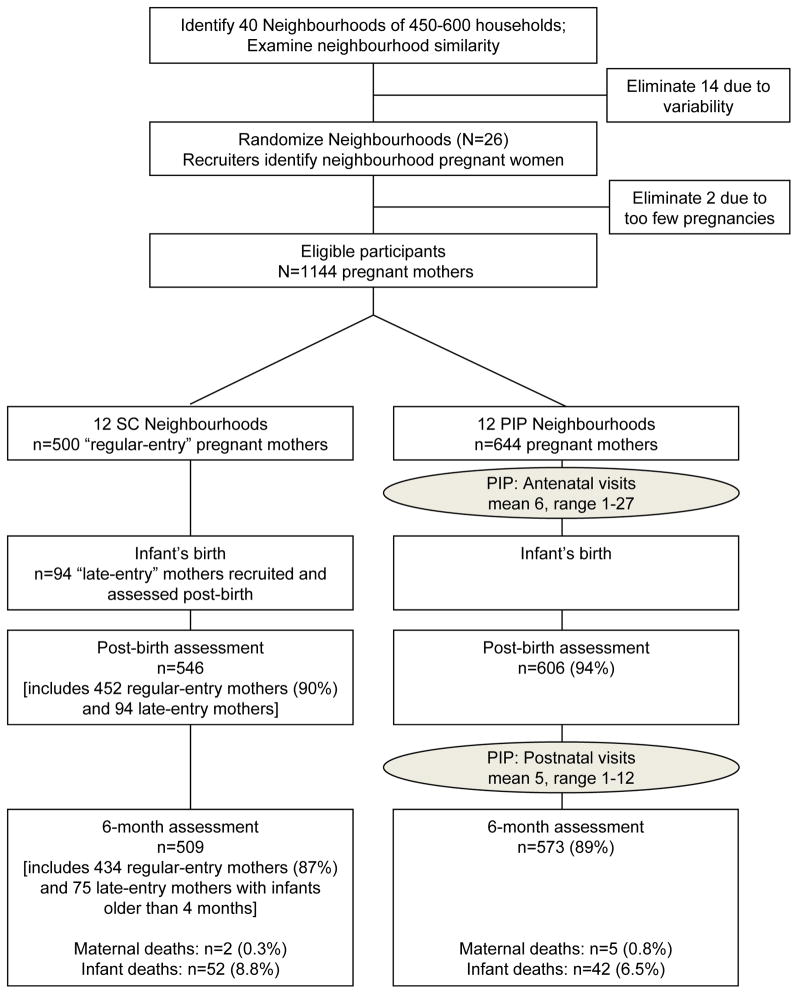

Figure 1 summarizes participant flow from recruitment to six months post-birth. Follow-up rates were similar across intervention conditions: 92% were reassessed post-birth (M=1.9 weeks; SD=2.1), 88% at six months (M=6.2 months, SD=0.7), and 88% were assessed at all three points. Due to delayed enrolment, late-entry participants were asked baseline, post-birth and 6-month questions in one assessment.

Figure 1.

Movement of participants through the trial at each assessment point for mothers in the Standard Care (SC) and the Philani Intervention Program (PIP).

Assessments

Township women were trained as interviewers, used mobile phones for data entry, and were routinely monitored and supervised. A driver transported all participants to a central assessment site, allowing interviewers to be blinded to condition. However, participants may have spontaneously talked about CHW to interviewers.

Measures

HIV-related preventive acts (self-reported) included asking partners to test for HIV; discussing HIV status with sexual partners in the past 3 months; and using condoms consistently (in 10 of the last 10 sexual episodes). All pregnant women reported whether they completed the rapid HIV test in the antenatal clinic, received their results, and completed a blood test to evaluate CD4 results. Among WLH, there were additional perinatal tasks that included knowledge of CD4 count and behaviours in the PMTCT cascade [18–19]: adherence to 1) AZT from the 28th week of pregnancy; 2) AZT during labour; 3) NVP during labour; 4) infant NVP post-birth; 5) infant AZT post-birth; 6) infant HIV PCR testing at six weeks and retrieval of results; and 7) maintenance of one feeding method (either breastfeeding or formula) for six months. We calculated the percentage of women completing each task and the percentage of women who cumulatively completed steps in the PMTCT cascade.

Child health and nutrition was assessed by low birth weight (LBW, <2500 grams) and by calculating z-scores based on WHO age- and gender-specific standards for weight, height/length, weight-for-height, and head circumference [20]. A z-score below -2 standard deviations was considered a serious growth deficit [21]. We monitored self-reports of months of breastfeeding (then dichotomised as longer than the sample median of 3 months), breastfeeding exclusively for six months, alcohol use the month before birth, and risky drinking post-birth, assessed by the AUDIT-C [22].

Healthcare was tracked by maternal reports of antenatal clinic visits, post-birth complications (heavy vaginal bleeding, malodorous discharge, fever, persistent cough, breast infection), and TB testing. The infant’s Road-to-Health card (RTHC) reported immunisations, clinic visits, and results of HIV PCR testing and formula feeding (allowing us to validate maternal self-reports of HIV status).

Mental health was measured by the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), using a cut-off of >13 to indicate depressed mood [23–24].

Social support was assessed by the frequency of material, emotional, and child-rearing support from family members, neighbours, and friends, and whether mothers applied for and received the child grant (R240/month, about 30 USD).

Analyses

Among WLH and among all mothers, we first looked for significant differences in baseline demographics between intervention conditions and between participants lost to follow-up versus those reassessed at post-birth and six months. For WLH and for all mothers, our primary analysis of the impact of the intervention at 6 months compared women in PIP and SC using a binomial test of the number of significant effects favouring PIP among our 28 measures. Our secondary analyses explored differences in individual outcomes between conditions among WLH and among all participants.

Primary analysis: binomial test for correlated outcomes

Comparisons between PIP and SC on 28 binary outcomes were tested at a one-sided upper-tail alpha=0.025 using logistic random effects regressions adjusting for neighbourhood clustering in SAS PROC GENMOD (version 9.2; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA). All models included an indicator variable for intervention status (1=PIP, 0=SC). Among WLH, we controlled for baseline employment because it differed significantly between intervention conditions; among all participants there were no significant baseline differences between conditions.

We can expect 28*0.025=0.7 significant tests (i.e. less than 1 of 28) on average if there are no differences between PIP and SC. If outcomes are independent, the probability that there are 3 or fewer significant differences is 99.5%, leading to a type 1 error of 0.005. However, the outcomes are likely positively correlated, which does not affect the expected number of positive tests, but does affect the variance of the number of positive tests. To study the effects of global positive correlation among all outcomes on the number of positive tests assuming no intervention effect, we treated each of our 28 tests as a normal z-test (z-statistics were assumed to come from an equi-correlated multivariate normal distribution) and simulated 40,000 trials of the number of significant outcomes, for z-tests having mutual correlations rho for rho running from 0 to 0.9 in steps of 0.1. We declared significance for z >1.96. Simulations were performed in R (version 2.11.1).

Across the 10 correlations, using a decision rule of rejecting the null of no PIP treatment effect given 4 or more significant tests of 28, the worst situation was that we reject the null with probability 0.059 when rho=0.7. For more reasonable correlations of rho=0.1 or 0.2, the actual type 1 error is 0.021 and 0.037, respectively. We estimated the average absolute correlations among the outcomes; because variables included “true dichotomies” (e.g. “Asked partner to test for HIV”) and indicators created by dichotomizing continuous outcomes (e.g. “Weight-for-age z-score ≥ −2”), we estimated both the Pearson and the tetrachoric correlations, planning to use whichever method produced higher average absolute correlations. If the correlations were found to be higher than 0.2, we would increase the needed number of significant results from 4 to 5 of 28 before declaring PIP’s significance. This would keep the type 1 error below 0.05, no matter what the outcomes’ correlations.

Since we performed two binomial tests, one for WLH and one for all women, we examined the p-values to see if each was below 0.05/2=0.025 to control for the family-wise error rate before declaring a significant result in favour of PIP.

Secondary analyses

We tested PIP’s impact on individual outcomes at a two-sided alpha=0.05 using the regressions described above. We used the same models to estimate PIP’s effect on completing all tasks in the PMTCT cascade. We considered our secondary analyses to be exploratory and retained the model p-values in lieu of a multiple-testing adjustment.

Late-entry participants with infants in the same age range as regular-entry participants’ infants at a particular assessment were included in analyses, when possible. Overall, results were similar whether or not late-entry participants’ data were included; results are available upon request.

Results

Baseline characteristics of overall sample

Table 1 summarises the self-reports of PIP and SC mothers at baseline. Women were similar across conditions on: outcome-related measures, such as HIV testing, receiving HIV test results, asking partners to test, knowledge of partner HIV status, alcohol use in pregnancy, rates of prior LBW infants, depression, and social support measures; matching criteria, such as housing type, water source, and presence of flush toilet and electricity on premises; demographic characteristics, including age, marital status, education, employment status, and household income; and general health, including HIV and TB infection rates. One significant baseline difference between PIP and SC was noted: among women who had been pregnant before, SC had a higher mean number of previous births. There were no significant selection effects between mothers who were successfully reassessed over the six months post-birth and those who were not. There were no serious study-related adverse events. Over 6 months, less than 1% of mothers died, and about 8% of infants died, similar across conditions.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of sample (N=1238) grouped by intervention condition: Philani Intervention Program (PIP, N=644) vs. Standard Care (SC, N=594). 1

| PIP (N=644) n (%) | SC (N=594) n (%) | Total (N=1238) n (%) | P-Value 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||

| Mean age (SD) | 26.5 (5.5) | 26.3 (5.6) | 26.4 (5.5) | 0.783 |

| Mean highest education level (SD) | 10.3 (1.8) | 10.3 (1.8) | 10.3(1.8) | 0.639 |

| Married or lives with partner | 377 (58.5) | 324 (54.6) | 701 (56.6) | 0.524 |

| Ever employed | 129 (20.0) | 104 (17.5) | 233 (18.8) | 0.341 |

| Monthly household income >2000 Rand | 280 (45.6) | 279 (48.1) | 559 (46.8) | 0.484 |

| Formal housing | 197 (30.6) | 191 (32.2) | 388 (31.3) | 0.958 |

| Water on site | 333 (51.7) | 327 (55.1) | 660 (53.3) | 0.983 |

| Flush toilet | 340 (52.8) | 343 (57.7) | 683 (55.2) | 0.923 |

| Electricity | 569 (88.4) | 543 (91.4) | 1112 (89.8) | 0.843 |

| Mother hungry past week | 312 (48.4) | 301 (50.7) | 613 (49.5) | 0.350 |

| Children hungry past week | 175 (27.2) | 185 (31.1) | 360 (29.1) | 0.054 |

| Maternal Health | ||||

| Non-primipara | 422 (65.5) | 394 (66.3) | 816 (65.9) | 0.714 |

| Mean number of live births (SD) | 1.5 (0.9) | 1.7 (1.1) | 1.6 (1.0) | 0.005* |

| Antenatal clinic appointment | 504 (78.3) | 376 (75.2) | 880 (76.9) | 0.330 |

| Tested for TB, lifetime | 206 (32.0) | 210 (35.4) | 416 (33.6) | 0.225 |

| Test positive TB, lifetime | 53 (8.2) | 50 (9.4) | 103 (8.8) | 0.438 |

| Mental Health | ||||

| EPDS > 13 | 238 (37.0) | 195 (32.8) | 433 (35.0) | 0.265 |

| HIV and Reproductive Health Behaviour | ||||

| Sexual partner, past 3 months | 580 (90.1) | 522 (87.9) | 1102 (89.0) | 0.284 |

| Knowledge of partner HIV status | 0.523 | |||

| Partner HIV+ | 46 (7.9) | 50 (9.6) | 96 (8.7) | |

| Partner HIV− | 325 (56.0) | 296 (56.7) | 621 (56.4) | |

| Partner serostatus unknown, or no response | 209 (36.0) | 176 (33.7) | 385 (34.9) | |

| Request partner HIV test | 391 (82.5) | 355 (83.1) | 746 (82.8) | 0.790 |

| Ever tested for HIV | 590 (91.6) | 550 (92.6) | 1140 (92.1) | 0.566 |

| Received HIV test results | 584 (99.0) | 547 (99.5) | 1131 (99.2) | 0.399 |

| Women living with HIV | 149 (25.5) | 146 (26.7) | 295 (26.1) | 0.649 |

| Mean number people disclosed to (SD) | 3.8 (4.5) | 5.0 (7.2) | 4.4 (6.0) | 0.104 |

| Sexual partner, past 3 months | 127 (85.2) | 125 (85.6) | 252 (85.4) | 0.947 |

| Disclosed to partner | 99 (73.9) | 105 (82.7) | 204 (78.2) | 0.140 |

| Knowledge of partner HIV status | 0.260 | |||

| Partner HIV+ | 42 (33.1) | 50 (40.0) | 92 (36.5) | |

| Partner HIV− | 13 (10.2) | 17 (13.6) | 30 (11.9) | |

| Partner serostatus unknown, or no response | 72 (56.7) | 58 (46.4) | 130 (51.6) | |

| Alcohol | ||||

| Drank any alcohol, month prior to pregnancy discovery | 155 (24.1) | 129 (25.8) | 284 (24.8) | 0.592 |

| AUDIT-C > 2, month prior to pregnancy discovery | 113 (17.6) | 101 (20.2) | 214 (18.7) | 0.323 |

| Drank any alcohol after pregnancy discovery | 56 (8.7) | 49 (9.8) | 105 (9.2) | 0.540 |

| AUDIT-C > 2, after pregnancy discovery | 41 (6.4) | 24 (4.8) | 65 (5.7) | 0.385 |

| Drank any alcohol, anytime during pregnancy | 172 (26.7) | 154 (25.9) | 326 (26.3) | 0.808 |

| Low Birth Weight (LBW) | ||||

| Previous LBW infants, among non-primiparous mothers | 61 (14.5) | 69 (17.5) | 130 (15.9) | 0.117 |

Sample size for SC includes 500 regular-entry controls and 94 late-entry controls.

P-values from linear (continuous variables), logistic (binary), or multinomial (categorical, >2 levels) random effects regressions, adjusted for neighbourhood clustering.

p<0.05

Post-birth and six-month outcome measures

WLH

At the baseline interview, 295 women reported an HIV+ serostatus. Between the baseline and six-month assessments, 59 additional women disclosed an HIV+ serostatus to the researchers (n=354, 29%). About 20% of WLH were prescribed lifelong ARV. At six months, 2% of WLH’s infants were HIV+.

The average absolute correlation between the 28 measures using the Pearson and the tetrachoric correlations was 0.088 and 0.202, respectively. As shown in Table 2, PIP outperformed SC on 6 of 28 outcomes, resulting in PIP having significantly better overall maternal and infant well-being over the first 6 months post-birth compared to SC using the binomial test (correlation=0.2, p=0.009).

Table 2.

Post-birth and 6-month health and well-being outcomes among women living with HIV (WLH, N=354), grouped by intervention condition: Philani Intervention Program (PIP, N=185) vs. Standard Care (SC, N=169).1

| PIP (N=185) n (%) | SC (N=169) n (%) | Estimated odds ratio, PIP vs. SC, (95% CI) 2 | 2-sided p-value 2 | 1-sided, upper tail p- value 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-related preventive acts | |||||

| Among mothers with a current sexual partner 3 | |||||

| Asked sexual partner to test for HIV at 6 months | 125 (91.9) | 103 (91.2) | 1.21 (0.57, 2.61) | 0.619 | 0.309 |

| Discussed HIV status with sexual partner at 6 months | 109 (80.1) | 96 (85.0) | 0.71 (0.34, 1.47) | 0.360 | 0.820 |

| Used a condom 10 of the last 10 times had intercourse at 6 months | 82 (60.3) | 61 (54.5) | 1.19 (0.65, 2.19) | 0.565 | 0.282 |

| Mother knows last CD4 count at 6 months | 145 (89.5) | 130 (92.9) | 0.51 (0.30, 0.89) | 0.017 | 0.992 |

| PMTCT | |||||

| Mother took AZT prior to labour, or full-ARVs PB | 169 (94.4) | 149 (93.7) | 1.08 (0.42, 2.80) | 0.868 | 0.434 |

| Mother took AZT during labour, or full-ARVs PB | 164(91.6) | 147 (92.5) | 0.87 (0.39, 1.95) | 0.741 | 0.630 |

| Mother took NVP tablet at onset of labour, or full-ARVs PB | 166 (92.7) | 142 (89.3) | 1.52 (0.70, 3.31) | 0.291 | 0.146 |

| Infant given NVP syrup within 24 hours of birth PB | 171 (95.5) | 141 (88.7) | 2.94 (1.41, 6.13) | 0.004 | 0.002* |

| AZT dispensed for infant and medicated as prescribed PB | 172 (96.1) | 142 (89.3) | 2.95 (1.12, 7.73) | 0.028 | 0.014* |

| Took infant to 6-week HIV PCR test and fetched results | 155 (96.9) | 132 (94.3) | 1.80 (0.62, 5.28) | 0.282 | 0.141 |

| One feeding method first 6 months: formula or breastfeeding | 96 (55.8) | 64 (42.1) | 1.81 (1.26, 2.62) | 0.002 | 0.001* |

| Child health and nutrition | |||||

| Birth weight ≥ 2500 grams PB | 156 (87.2) | 123 (80.9) | 1.27 (0.89, 1.82) | 0.185 | 0.093 |

| Weight-for-age z-score ≥ −2 at 6 months | 163 (98.2) | 147 (97.4) | -- -- | -- | --4 |

| Height-for-age z-score ≥ −2 at 6 months | 146 (88.5) | 118 (79.7) | 1.63 (1.11, 2.39) | 0.013 | 0.006* |

| Weight-for-height z-score ≥ −2 at 6 months | 159 (95.8) | 146 (98.0) | 0.50 (0.13, 1.96) | 0.321 | 0.840 |

| Head-circumference-for-age z-score ≥ −2 at 6 months | 163 (98.2) | 138 (93.2) | -- -- | -- | --4 |

| Number of months breastfed exclusively > median of 3 | 8 (50.0) | 9 (37.5) | 1.62 (0.46, 5.73) | 0.458 | 0.229 |

| Exclusive breastfeeding first 6 months | 4 (2.3) | 2 (1.3) | 1.93 (0.39, 9.61) | 0.420 | 0.210 |

| Drank no alcohol the month prior to giving birth PB | 169 (91.4) | 141 (91.0) | 0.99 (0.46, 2.12) | 0.970 | 0.515 |

| No risky drinking at 6 months (AUDIT-C score ≤ 2) | 152 (88.4) | 139 (89.1) | 0.85 (0.44, 1.66) | 0.641 | 0.680 |

| Healthcare and monitoring | |||||

| 4 or more antenatal clinic visits (4 is standard practice) PB | 142 (83.5) | 136 (83.4) | 0.98 (0.52, 1.85) | 0.958 | 0.521 |

| Mother free of post-birth complications through 6 months 5 | 34 (18.4) | 15 (8.9) | 2.26 (1.34, 3.81) | 0.002 | 0.001* |

| Mother tested for TB at 6 months | 23 (13.4) | 19 (13.8) | 0.84 (0.49, 1.43) | 0.517 | 0.742 |

| Number of 6-month RTHC immunisations > median of 11 (16 total) | 57 (42.5) | 61 (46.2) | 0.91 (0.65, 1.27) | 0.575 | 0.712 |

| Mental health | |||||

| Not depressed at 6 months (EPDS ≤ 13) | 124 (72.1) | 114 (73.1) | 0.86 (0.57, 1.30) | 0.474 | 0.763 |

| Social support | |||||

| 6-month number of close friends or relatives x frequency of contact > median of 20.5 6 | 85 (49.4) | 79 (50.6) | 0.92 (0.55, 1.53) | 0.739 | 0.631 |

| Father acknowledged infant to family at 6 months | 162 (98.2) | 141 (91.6) | 4.66 (1.53, 14.19) | 0.007 | 0.003* |

| Receiving child support grant at 6 months | 77 (65.8) | 65 (62.5) | 1.07 (0.61, 1.85) | 0.822 | 0.411 |

Sample size reflects participants available post-birth or at six months (N=354). Post-birth outcomes are indicated using PB; other outcomes are from the six-month assessment. Sample sizes for each assessment: Post-birth assessment: PIP (N=185), SC (N=168, including 145 regular-entry controls and 23 late-entry controls), total (N=353). Six-month assessment: PIP (N=172), SC (N=156, including 138 regular-entry controls and 18 late-entry controls with infants older than 4 months), total (N=328).

Random effects logistic regression, adjusted for neighbourhood clustering, controlling for baseline employment. 1-sided p-value used in the binomial test; 2-sided p-value used in the secondary analysis of individual outcomes.

Measures assessed for mothers with a current sexual partner: PIP (N=137), SC (N=113), total (N=250).

Model failed to converge.

Post-birth complications include heavy vaginal bleeding, malodorous discharge, fever, persistent cough, and breast infection. 6. Median number of close friends or relatives: 2. Median frequency of contact in past month: 7.5.

1-sided, upper tail p<0.025.

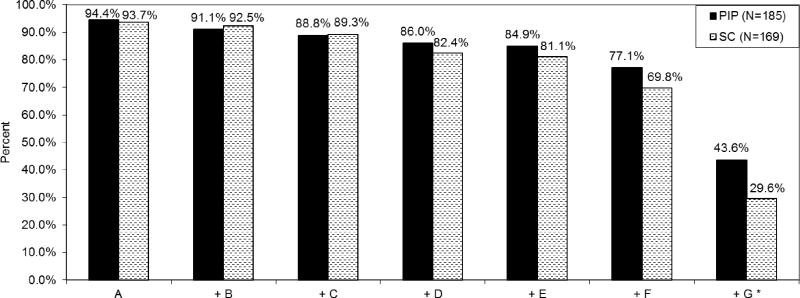

On specific PMTCT tasks (Table 2), WLH were similar across conditions in the percentage of WLH adhering to ARVs surrounding childbirth and seeking infant PCR testing. PIP WLH were more likely to administer infant NVP at birth (OR=2.94; 2-sided p=0.004), correctly medicate infants with AZT (OR=2.95; p=0.028), and practise one feeding method for the first 6 months (OR=1.81; p=0.002). Cumulative completion of the tasks in the PMTCT cascade (Figure 2) was greater in PIP compared to SC (OR=1.95; p<0.001). Furthermore, compared to SC, PIP WLH were more likely to have infant height-for-age z-score ≥ −2 (OR=1.63; p=0.013), be free of post-birth complications (OR=2.26; p=0.002), and have the father acknowledge the infant to his family (OR=4.66, p=0.007). However, PIP WLH were less likely than SC WLH to know their CD4 count (OR=0.51, p=0.017).

Figure 2.

Adherence to cumulative behaviours in the PMTCT cascade among women living with HIV (WLH, N=354), by intervention condition: Philani Intervention Program (PIP, N=185) vs. Standard Care (SC, N=169).

Key: A. Maternal AZT prior to labour, or full ARVs

B. Maternal AZT during labour, or full ARVs

C. Maternal NVP at onset of labour, or full ARVs

D. Infant NVP within 24 hours of birth

E. Infant AZT dispensed and medicating as prescribed

F. Infant HIV PCR test and results

G. One feeding method first 6 months

Note: "+" indicates that the behaviour listed includes itself and all behaviours listed to the left: cumulative adherence.

*Estimated OR, PIP vs. SC (95% CI): 1.95 (1.36, 2.79); p<0.001. From random effects logistic regression, adjusted for neighbourhood clustering, controlling for baseline employment.

Overall sample

The average absolute correlation between the 28 measures among the full sample using the Pearson and the tetrachoric correlations was 0.075 and 0.173, respectively. As shown in Table 3, PIP out-performed SC on 7 of 28 outcomes; thus, using the binomial test, we can declare PIP to have resulted in significantly better overall maternal and infant well-being over the first 6 months post-birth compared to SC (correlation=0.2, p=0.005).

Table 3.

Post-birth and 6-month health and well-being outcomes among all participants (N=1157), grouped by intervention condition: Philani Intervention Program (PIP, N=608) vs. Standard Care (SC, N=549).1

| PIP (N=608) n (%) | SC (N=549) n (%) | Estimated odds ratio, PIP vs. SC, (95% CI) 2 | 2-sided p-value 2 | 1-sided, upper tail p-value 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-related preventive acts | |||||

| Among mothers with a current sexual partner 3 | |||||

| Asked sexual partner to test for HIV at 6 months | 382 (87.8) | 309 (83.5) | 1.42 (0.96, 2.11) | 0.078 | 0.039 |

| Discussed HIV status with sexual partner at 6 months | 326(74.9) | 286 (77.3) | 0.88 (0.65, 1.20) | 0.412 | 0.794 |

| Used a condom 10 of the last 10 times had intercourse at 6 months | 189 (43.5) | 124 (33.6) | 1.52 (1.16, 1.99) | 0.002 | 0.001* |

| Among HIV+ mothers 4 | |||||

| Mother knows last CD4 count at 6 months | 145 (89.5) | 130 (92.9) | 0.51 (0.30, 0.89) | 0.017 | 0.992 |

| PMTCT | |||||

| Mother took AZT prior to labour, or full-ARVs PB | 169 (94.4) | 149 (93.7) | 1.08 (0.42, 2.80) | 0.868 | 0.434 |

| Mother took AZT during labour, or full-ARVs PB | 164 (91.6) | 147 (92.5) | 0.87 (0.39, 1.95) | 0.741 | 0.630 |

| Mother took NVP tablet at onset of labour, or full-ARVs PB | 166 (92.7) | 142 (89.3) | 1.52 (0.70, 3.31) | 0.291 | 0.146 |

| Infant given NVP syrup within 24 hours of birth PB | 171 (95.5) | 141 (88.7) | 2.94 (1.41, 6.12) | 0.004 | 0.002* |

| AZT dispensed for infant and medicated as prescribed PB | 172 (96.1) | 142 (89.3) | 2.95 (1.12, 7.73) | 0.028 | 0.014* |

| Took infant to 6-week HIV PCR test and fetched results | 155 (96.9) | 132 (94.3) | 1.80 (0.62, 5.28) | 0.282 | 0.141 |

| One feeding method first 6 months: formula or breastfeeding | 96 (55.8) | 64 (42.1) | 1.81 (1.26, 2.62) | 0.002 | 0.001* |

| Child health and nutrition | |||||

| Birth weight ≥ 2500 grams PB | 520 (90.1) | 426 (87.1) | 1.35 (1.00, 1.83) | 0.051 | 0.025 |

| Weight-for-age z-score ≥ −2 at 6 months | 541 (97.8) | 475 (97.5) | 1.13 (0.59, 2.14) | 0.715 | 0.357 |

| Height-for-age z-score ≥ −2 at 6 months | 496 (90.8) | 414 (85.5) | 1.69 (1.22, 2.34) | 0.002 | 0.001* |

| Weight-for-height z-score ≥ −2 at 6 months | 526 (95.6) | 470 (97.1) | 0.62 (0.36, 1.06) | 0.079 | 0.961 |

| Head-circumference-for-age z-score ≥ −2 at 6 months | 537 (97.6) | 462 (95.7) | 1.88 (0.92, 3.81) | 0.081 | 0.041 |

| Number of months breastfed exclusively > median of 3 | 197 (49.5) | 85 (23.9) | 3.08 (2.17, 4.37) | <0.001 | <0.001* |

| Exclusive breastfeeding first 6 months | 59 (10.3) | 15 (3.1) | 3.59 (1.91, 6.75) | <0.001 | <0.001* |

| Drank no alcohol the month prior to giving birth PB | 566 (93.6) | 443 (90.8) | 1.50 (0.87, 2.58) | 0.144 | 0.072 |

| No risky drinking at 6 months (AUDIT-C score ≤ 2) | 526 (91.8) | 469 (92.1) | 0.97 (0.60, 1.57) | 0.893 | 0.553 |

| Healthcare and monitoring | |||||

| 4 or more antenatal clinic visits (4 is standard practice) PB | 474 (82.7) | 439 (82.7) | 1.00 (0.74, 1.34) | 0.992 | 0.504 |

| Mother free of post-birth complications through 6 months 5 | 127 (20.9) | 102 (18.6) | 1.16 (0.86, 1.57) | 0.342 | 0.171 |

| Mother tested for TB at 6 months | 72 (12.6) | 57 (13.1) | 0.95 (0.66, 1.36) | 0.777 | 0.612 |

| Number of 6-month RTHC immunisations > median of 11 (16 total) | 179 (39.2) | 185 (44.2) | 0.81 (0.61, 1.09) | 0.163 | 0.918 |

| Mental health | |||||

| Not depressed at 6 months (EPDS ≤ 13) | 444 (77.5) | 413 (81.1) | 0.80 (0.59, 1.08) | 0.148 | 0.926 |

| Social support | |||||

| 6-month number of close friends or relatives x frequency of contact > median of 16 6 | 271 (47.3) | 264 (51.9) | 0.85 (0.62, 1.17) | 0.318 | 0.841 |

| Father acknowledged infant to family at 6 months | 536 (95.5) | 475 (94.8) | 1.17 (0.65, 2.13) | 0.602 | 0.301 |

| Receiving child support grant at 6 months | 233 (64.5) | 213 (66.6) | 0.92 (0.68, 1.23) | 0.572 | 0.714 |

Sample size reflects participants available post-birth or at six months (N=1157). Post-birth outcomes are indicated using PB; other outcomes are from the six-month assessment. Sample sizes for each assessment: Post-birth assessment: PIP (N=606), SC (N=546, including 452 regular-entry controls and all 94 late-entry controls), total (N=1152). Six-month assessment: PIP (N=573), SC (N=509, including 434 regular-entry controls and 75 late-entry controls with infants older than 4 months), total (N=1082).

Random effects logistic regression, adjusted for neighbourhood clustering. Models for outcomes among HIV+ mothers control for baseline employment. 1-sided p-value used in the binomial test; 2-sided p-value used in the secondary analysis of individual outcomes.

Measures assessed for mothers with a current sexual partner: PIP (N=437), SC (N=372), total (N=809).

Measures assessed for HIV+ mothers: PIP (N=185), SC (N=169), total (N=354).

Post-birth complications include heavy vaginal bleeding, malodorous discharge, fever, persistent cough, and breast infection.

Median number of close friends or relatives: 2. Median frequency of contact in past month: 7.

1-sided, upper tail p<0.025.

PIP and SC mothers and infants differed significantly on individual outcomes. HIV prevention differed by condition: consistent condom use was higher in PIP compared to SC (OR=1.52; 2-sided p=0.002), and, as described previously, there were significant differences in adherence to PMTCT tasks. Furthermore, PIP infants were more likely to have height-for-age z-score ≥ −2 (OR=1.69; p=0.002), breastfeed longer than the median number of three months (OR=3.08; p<0.001), and breastfeed exclusively for six months post-birth (OR=3.59; p<0.001). Healthcare, maternal depression, social support, and the percentage of mothers securing the child grant were similar across conditions.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of a CHW model for delivering home-based preventive care by addressing multiple health issues. We focussed on the issues most salient in pregnancy in South Africa: HIV, alcohol use, and perinatal care. These were concurrently addressed with a model of pragmatic problem solving with cognitive-behavioural intervention strategies. The South African government has begun to implement a similar model through a process they have termed “re-engineering primary healthcare” [25] and plans to deploy about 65,000 CHWs. We found significant benefits in overall maternal and infant well-being for WLH and all neighbourhood women and demonstrated the specific domains of improvement, especially for WLH. This model may be useful for countries that aim to promote task-shifting from professionals to CHWs in order to achieve HIV reduction and their Millennium Development Goals [1].

The gains for WLH and their children were broader than only adhering to PMTCT tasks. WLH and their children face life-long challenges, and home visits by CHW create a vehicle for providing on-going support to WLH and all community women. By having CHW identified with a maternal, child health and nutrition program, much of the stigma associated with HIV is sidestepped. By focusing training on generic, common principles of behaviour change and the specific health challenges of the local community, the potential exists to broadly diffuse the training model [26–27], allowing tailoring to the prevailing local diseases. Consistent with previous recommendations [28], the implementation was mounted by an agency with strong ties to community leaders, stakeholders, and clinical care sites; by CHW who received a stipend to sustain the program; and following stringent supervision standards.

All neighbourhoods (PIP and SC), had nearby access to clinic and hospital services, which provided access to dual ARV regimens for PMTCT. In the Cape Town area, PMTCT adherence rates are higher than in many parts of South Africa. In fact, the PMTCT adherence rates of WLH in SC exceeded those observed in other studies of pregnant women in South Africa [29]. Yet, the odds of completing all PMTCT tasks were 1.95 times higher in PIP than SC.

The gains from our study are significant, but modest. However, small gains often become magnified over time. Pregnancy and infancy are critical developmental phases with lifelong consequences; small changes that become habits can have substantial impact over a lifetime [10, 30]. Since our trial’s primary endpoint is 18 months, we are continuing to monitor outcomes and will report final results when the trial is complete.

A universal goal in crafting interventions is sustainability. CHW visited families on average 6 times during pregnancy and 5 times between birth and 2 months post-birth. This is substantially more intensive than most vertical, single-disease-targeted interventions that have been implemented in South Africa and globally. However, PIP has been on-going since the 1990s and CHWs’ salaries and experience are in line with South African government guidelines [31–32] and would therefore be sustainable. In addition to sustainability, home visits offer a viable strategy to circumvent challenges associated with obtaining healthcare from clinics. Clinic appointments are difficult to schedule; waiting lines are long; transport is expensive; and mothers must coordinate their own and infants’ care across multiple clinics [32–33]. A CHW approach grounded in cognitive-behavioural skills, with locally-tailored content addressing local health risks, may be a strategy that is scalable globally.

A noteworthy innovation was the use of mobile phones for data collection, and monitoring and supporting CHW [34]. Supervision and field support have often been major barriers to consistent, sustained CHW performance [35]. Mobile phones provided a tool for routine feedback in our study, and proved to be an effective supervisory tool especially when combined with in-person supervision.

More than one million additional professional healthcare workers are required to meet existing health demands [36]. Task-shifting from healthcare professionals to CHWs has the potential to address this need [13]. PIP provided both task-shifting and site-shifting (from clinics to communities). It allows governments to leverage the investments in HIV to address concurrent health issues. PIP offers an intervention model and evaluation strategy for building sustainable, locally-tailored CHW home visiting programs.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding and Conflicts of Interest: This study was funded by NIAAA Grant # 1R01AA017104 and supported by NIH grants MH58107, 5P30AI028697, and UL1TR000124. Mark Tomlinson is supported by the National Research Foundation (South Africa). No conflicts of interest were declared.

Ingrid M. le Roux, Mark Tomlinson, Robert E. Weiss and Mary Jane Rotheram-Borus conceived of the study, planned the study design, and led preparation of the manuscript. Robert E. Weiss designed the data analyses and Jessica M. Harwood conducted the data analyses and authored sections of the manuscript. Mary J. O’Connor, Robert E. Weiss, Carol M. Worthman, Dallas Swendeman, and W. Scott Comulada consulted on study design, measure selection, data analyses, and edited and commented on the manuscript. Nokwanele Mbewu, Jacqueline Stewart, and Mary Hartley led study implementation, authored sections, and commented on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov registration # NCT00996528

Competing Interests, Financial Disclosure, and Licensing

No authors have any competing interests. All authors have completed the Authorship Responsibility, Financial Disclosure, and Copyright Transfer form and declare no conflicts of interest: no support from any organisation for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, a worldwide licence to the Publishers and its licensees in perpetuity, in all forms, formats and media (whether known now or created in the future), to i) publish, reproduce, distribute, display and store the Contribution, ii) translate the Contribution into other languages, create adaptations, reprints, include within collections and create summaries, extracts and/or abstracts of the Contribution, iii) create any other derivative work(s) based on the Contribution, iv) to exploit all subsidiary rights in the Contribution, v) the inclusion of electronic links from the Contribution to third party material where-ever it may be located; and, vi) licence any third party to do any or all of the above.

Contributor Information

Ingrid M. LE ROUX, Philani Maternal, Child Health and Nutrition Project, Cape Town, South Africa; PO Box 40188, Elonwabeni, Cape Town, 7791 South Africa.

Mark TOMLINSON, Department of Psychology, Stellenbosch University, South Africa; Private Bag X1 Matieland, 7602 South Africa.

Jessica M. HARWOOD, Center for Community Health, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA),10920 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 350, Los Angeles, CA 90024 USA.

Mary J. O’CONNOR, Department of Psychiatry, David Geffen School of Medicine, UCLA, 760 Westwood Plaza, 68-265A Semel Institute, Los Angeles, CA 90095 USA.

Carol M. WORTHMAN, Emory University, 1557 Pierce Drive, Atlanta, GA 30322 USA.

Nokwanele MBEWU, Philani Maternal, Child Health and Nutrition Project, Cape Town, South Africa; PO Box 40188, Elonwabeni, Cape Town, 7791 South Africa.

Jacqueline STEWART, Stellenbosch University, South Africa; Private Bag X1 Matieland, 7602 South Africa.

Mary HARTLEY, Stellenbosch University, South Africa; Private Bag X1 Matieland, 7602 South Africa.

Dallas SWENDEMAN, Psychiatry & Biobehavioral Sciences, UCLA, 10920 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 350, Los Angeles, CA 90024 USA.

W. Scott COMULADA, Psychiatry & Biobehavioral Sciences, UCLA, 10920 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 350, Los Angeles, CA 90024 USA.

Robert E. WEISS, Department of Biostatistics, Fielding School of Public Health, UCLA, 650 Charles E. Young Drive South, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1772 USA.

Mary Jane ROTHERAM-BORUS, Global Center for Children and Families, UCLA, 10920 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 350, Los Angeles, CA 90024 USA.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. [Accessed on July 31, 2012];Millennium Development Goals. Available at http://www.who.int/topics/millennium_development_goals/en/

- 2.Grantham-McGreggor S on behalf of the International Committee on Child Development Committee. Correspondence: Early child development in developing countries. Lancet. 2007;369:824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60404-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.USAID. [Accessed on December 14, 2011];Maternal Health in South Africa. Available at http://www.usaid.gov/our_work/global_health/mch/mh/countries/southafrica.html.

- 4.Alamo S, Wabwire-Mangen F, Kenneth E, Sunday P, Laga M, Colebunders RL. Task-shifting to community health workers: evaluation of the performance of a peer-led model in an antiretroviral program in Uganda. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(2):101–7. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ospina JE, Orcau A, Millet JP, Sánchez F, Casals M, Caylà JA. Community health workers improve contact tracing among immigrants with tuberculosis in Barcelona. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:158. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Community Agency for Social Inquiry. [Accessed on July 31, 2012];Phasing in the Child Support Grant: A social impact study. Available at http://www.case.org.za/~caseorg/images/docs/child_support_grant.pdf. Published July 2000.

- 7.Peacock S, Konrad S, Watson E, Nickel D, Muhajarine N. Effectiveness of home visiting programs on child outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young SD, Hlavka Z, Modiba P, Gray G, Paeds FC, Van Rooyen H, et al. HIV-Related Stigma, Social Norms, and HIV Testing in Soweto and Vulindlela, South Africa: National Institutes of Mental Health Project Accept (HPTN 043) J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:620–624. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fc6429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olds DL, Robinson J, Pettitt L, Luckey DW, Holmberg J, Ng RK, et al. Effects of home visits by paraprofessionals and by nurses: Age 4 follow-up results of a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1560–1568. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olds DL, Kitzman H, Cole R, Robinson J, Sidora K, Luckey DW, et al. Effects of nurse home-visiting on maternal life course and child development: Age 6 follow-up results of a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1550–1559. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olds D, Hill P, Rumsey E. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Washington DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; [Accessed on December 14, 2001]. Prenatal and early childhood nurse home visitation. No. NCJ-172875. Available at https://www.ncjrs.gov/html/ojjdp/172875/contents.html. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olds DL, Robinson J, O’Brien R, Luckey DW, Pettitt LM, Henderson CR, Jr, et al. Home visiting by paraprofessionals and by nurses: A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2002;110(3):486–496. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.3.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Global recommendations and Guidelines. Geneva: 2008. [Accessed on October 24, 2012]. Treat Train Retrain. Task shifting: rational redistribution of tasks among health workforce teams. Available at http://www.who.int/healthsystems/TTR-TaskShifting.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haines A, Sanders D, Lehmann U, Rowe AK, Lawn JE, Jan S, et al. Achieving child survival goals: potential contribution of community health workers. Lancet. 2007;369:2121–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meichenbaum D. Cognitive behavioral therapy: an integrative approach. New York: Plenum Behaviour Therapy Series; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rotheram-Borus MJ, le Roux IM, Tomlinson M, Mbewu N, Comulada WS, le Roux K, et al. Philani Plus (+): a randomized controlled trial of Mentor Mother home visiting program to improve infants’ outcomes. Prev Sci. 2011;12(4):372–388. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0238-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Connor MJ, Whaley SE. Brief intervention for alcohol use by pregnant women. Am J Pub Health. 2007;97:252–258. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.077222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.South Africa National Department of Health. [Accessed October 17, 2012];Policy and guidelines for the implementation of the PMTCT programme. Available at http://southafrica.usembassy.gov/root/pdfs/2008-pmtct.pdf. Published February 11, 2008.

- 19.Marcos Y, Ryan Phelps B, Bachman G. Community strategies that improve care and retention along the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV cascade: a review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15(Suppl 2):17394. doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.4.17394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: Methods and development. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cogill B. Anthropometric Indicators Measurement Guide. Washington DC: Food and Nutritional Technical Assistance Project; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS. The AUDIT-C: screening for alcohol use disorders and risk drinking in the presence of other psychiatric disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2005;46:405–416. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chibanda D, Mangezi W, Tshimanga M, Woelk G, Rusakaniko P, Stranix-Chibanda L, et al. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale among women in a high HIV prevalence area in urban Zimbabwe. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2010;13(3):201–206. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartley M, Tomlinson M, Greco E, Comulada WS, Stewart J, le Roux I, et al. Depressed mood in pregnancy: Prevalence and correlates in two Cape Town peri-urban settlements. BMC Reproductive Health. 2011;8:9. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohapi MC, Basu D. PHC re-engineering may relieve overburdened tertiary hospitals in South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2012;102:79–80. doi: 10.7196/samj.5443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Chorpita B. Disruptive Innovations for Designing and Diffusing Evidence-based Interventions. American Psychologist. 2012;67(6):463–476. doi: 10.1037/a0028180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaudhary N, Mohanty PN, Sharma M. Integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI) follow-up of basic health workers. Indian J Pediatr. 2005;72(9):735–739. doi: 10.1007/BF02734143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nyonator F, et al. The Ghana Community-based Health Planning and Services Initiative for scaling up service delivery innovation. Health Policy and Planning. 2005;20(1):25–34. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czi003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rollins N, Coovadia HM, Bland RM, Coutsoudis A, Bennish M, Patel D, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in HIV-infected and uninfected women in rural and urban South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44(3):321–328. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802ea4b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martorell R, Horta BL, Adair LS, Stein AD, Richter L, Fall CHD, et al. Weight gain in the first two years of life is an important predictor of schooling outcomes in pooled analyses from five birth cohorts from low- and middle-income countries. J Nutr. 2010;140(2):348–54. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.112300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magongo B. [Accessed August 9, 2012];Community Health Workers in Gauteng – Context and Policy. 2004 Available at http://www.cadre.org.za/files/PolicyCHWs.pdf.

- 32.University of the Western Cape. [Accessed on August, 1, 2012];Re-engineering primary health care for South Africa: Focus on ward based primary health care outreach teams. Available at http://www.uwc.ac.za/usrfiles/users/280639/CHW_symposium-NationalPHC_Reenginnering.pdf. Published June 7, 2012.

- 33.Sprague C, Chersich MF, Black V. Health system weakness constrain access to PMTCT and maternal HIV services in South Africa: A qualitative overview. AIDS Research Therapy. 2011;8:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomlinson M, Solomon W, Singh Y, Doherty T, Chopra M, Ijumba P, et al. The use of mobile phones as a data collection tool: A report from a household survey in South Africa. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2009;9:51. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-9-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewin S, Babigumira SM, Bosch-Capblanch X, Aja G, van Wyk B, Glenton C, et al. [Accessed on October 24, 2012];Lay health workers in primary and community health care: a systematic review of trials. 2006 1:Art. No., CD004015. Available at http://www.who.int/rpc/meetings/LHW_review.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kenenchukwu M, Llewleyn M. Compensation for the brain drain from developing countries. Lancet. 2009;373:1665–1666. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60927-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]