Abstract

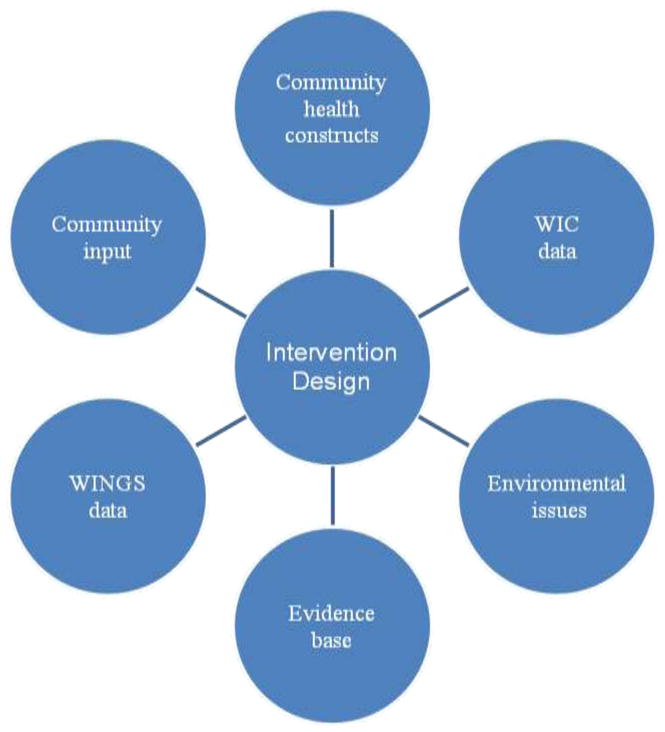

Healthy Children, Strong Families (HCSF) is a 2-year, community-driven, family-based randomized controlled trial of a healthy lifestyles intervention conducted in partnership with four Wisconsin American Indian tribes. HCSF is composed of 1 year of targeted home visits to deliver nutritional and physical activity curricula. During Year 1, trained community mentors work with 2–5-year-old American Indian children and their primary caregivers to promote goal-based behavior change. During Year 2, intervention families receive monthly newsletters and attend monthly group meetings to participate in activities designed to reinforce and sustain changes made in Year 1. Control families receive only curricula materials during Year 1 and monthly newsletters during Year 2. Each of the two arms of the study comprises 60 families. Primary outcomes are decreased child BMI z-score and decreased primary caregiver BMI. Secondary outcomes include: increased fruit/vegetable consumption, decreased TV viewing, increased physical activity, decreased soda/sweetened drink consumption, improved primary caregiver biochemical indices, and increased primary caregiver self-efficacy to adopt healthy behaviors. Using community-based participatory research and our history of university–tribal partnerships, the community and academic researchers jointly designed this randomized trial. This article describes the study design and data collection strategies, including outcome measures, with emphasis on the communities’ input in all aspects of the research.

Keywords: Obesity, American Indian, Nutrition, Physical activity, Intervention

Introduction

Similar to obesity trends in American Indian (AI) adults, obesity rates in AI children are steadily increasing and are higher than those in all other racial/ethnic groups combined in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Pediatric Nutrition Surveillance System estimates that AI children (ages 2–5 years) have the highest rates for overweight and obesity (40%) among children of all racial/ethnic groups (31.2%) (CDC, 2009). Moreover, the prevalence rate has leveled off for all racial/ethnic groups except AI children, whose rates continue to increase (Polhamus et al., 2009).

Our research in three AI communities in Wisconsin, the Wisconsin Nutrition and Growth Study (WINGS), also showed high obesity rates in AI children. Of the 445 children aged 5–8 years participating in WINGS, 27% were obese (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 95th percentile) and an additional 19% were overweight (BMI > 85th percentile and < 95th percentile) (Adams & Prince, 2010). Estimates of obesity in AI children from WINGS and from other AI study samples (Great Lakes EpiCenter, 2005; Lindsay et al., 2002; Salbe et al. 2002) suggest that obesity starts early in childhood. Wisconsin AI parents and primary caregivers also do not recognize that children are overweight, or that excess weight is related to health consequences later in life (Adams et al., 2005). Therefore, early childhood interventions are urgently needed for AI families to encourage healthy eating and activity patterns.

National recommendations identify parents, as well as community environments, to be key actors in the prevention of obesity (Koplan et al., 2005). Research has shown that parental involvement is important for both prevention and treatment of childhood obesity (Golan & Crow, 2004; Golan et al., 1998; Epstein, 1996; Wrotniak et al., 2004; St. Jeor et al., 2002). Research also supports focusing on younger children because of the national trend of obesity beginning at earlier ages (< 5 years) (National Center for Health Statistics, 2001). However, little research has been done on obesity prevention for preschool children and their families. A recent review found that only a limited number of interventions has been implemented in either home or community settings (Flynn et al., 2006). Moreover, few obesity prevention trials have focused on 2–5-year-olds, an age range where upward crossing of BMI/weight percentiles is recognized as a risk for later obesity.

This article provides an overview of the design and community participation in a two-arm, family-based randomized controlled trial of an intervention called Healthy Children, Strong Families (HCSF). HCSF was designed based on the hypothesis that directly addressing obesity prevention in the home environment and involving the primary caregiver is essential in the prevention of AI child obesity. Our study tests whether a mentored, home-based healthy lifestyle intervention targeting both AI primary caregivers and their 2–5-year-old children will reduce AI child overweight.

Research Design and Methods

Participatory Process for Research Design

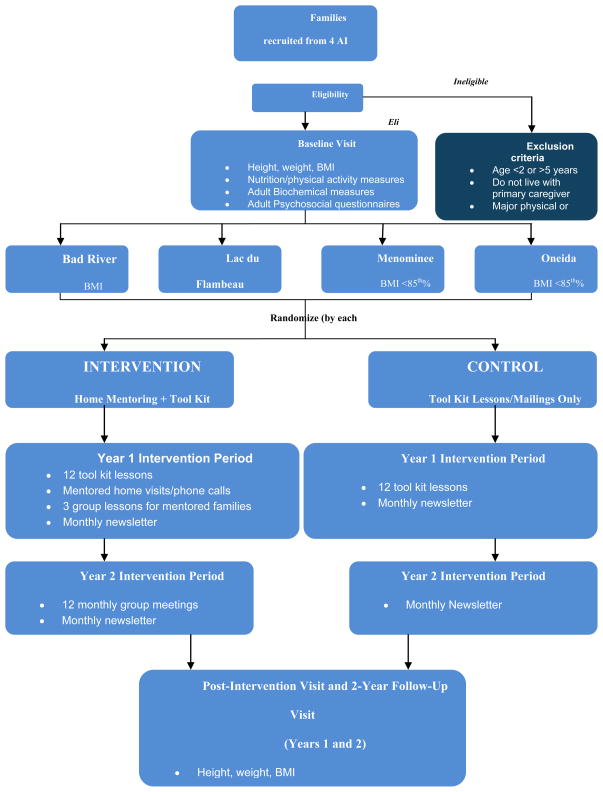

Our previous WINGS research with three Wisconsin AI communities included principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR) in gathering baseline data on the prevalence of and contributing factors to pediatric obesity (Adams et al., 2004). Data generated by WINGS provided a foundation for building intervention strategies. Increased trust and mutual gain in knowledge, byproducts of the participatory relationship, were essential in developing the next step of intervention. Community members and tribal leaders were integral throughout the conceptualization and planning of the HCSF intervention. Members from health, education, child welfare, and tribal government bodies of the three initial participating communities met with researchers at a collaboration meeting in July 2004 to discuss WINGS results and possible interventions. During this meeting, ideas for intervention included: involving parents, using an intergenerational model, focusing on young children, nutrition education, role modeling, forming partnerships between organizations, and incorporating family events. Subsequent meetings focused on project feasibility, research design, duration, randomization and recruitment strategies, and potential partners. Figure 1 illustrates the various contributions by the community and investigators to the design of HCSF. Throughout the HCSF project, key community personnel, primarily in the health and education sectors, have played important roles in project promotion, subject recruitment, data collection, and dissemination of results.

Fig. 1.

Sources of information for designing Healthy Children, Strong Families

Overview of Intervention

HCSF is based on social cognitive and family systems theories (Burnet et al., 2002; Golan & Crow, 2004; Bandura, 2004) and seeks to change behaviors at the family level. We posit that primary caregivers can increase knowledge, increase self-efficacy, set goals, and make necessary lifestyle changes for their families with appropriate support from mentors. In addition, it is based upon an AI approach of elders teaching life-skills to the next generation and reinforcing the cultural values of traditional foods and activity. HCSF aims to change behaviors not only through increased knowledge of healthy lifestyles but also through enhanced parenting skills and increased self-efficacy. This is facilitated by mentored parent coaching (Year 1), along with ongoing mentored family and group support (Year 2). Based on our prior research in Wisconsin AI children (Adams et al., 2008), we believe obesity prevention interventions should be targeted at preschool ages.

Furthermore, obesity prevention in AI children may be more successful by using a family-based model facilitated through home-visiting mentors who involve parents in engaging in their own behavior change (Worobey et al., 2004; McNaughton, 2004; Drummond et al., 2002; Williams et al,. 2004; Lindsay et al., 2006). The mentors address self-efficacy and family support systems that are essential factors, along with nutritional and physical activity behaviors, to sustain a healthy lifestyle. Mentors are respected members of the community who understand cultural norms and values. Approval for the study was obtained from the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Health Sciences IRB and each tribe’s Head Start and Tribal Council.

Subjects and Recruitment

Participating communities

Three Wisconsin tribes—Menominee, Lac du Flambeau, and Bad River—have been partners with the University of Wisconsin–Madison research team for over 10 years. The Oneida Tribe has been a partner for the past 4 years. All four tribes have Head Start programs (including two sites at Menominee and three at Oneida) and all are involved in the HCSF project. Tribal Head Start programs served as primary recruitment sites, as the majority of preschool children attend a Head Start center. Materials were distributed via children’s backpacks, parent mailings, and tribal research staff attending Head Start events. A newsletter for all Head Start families was developed highlighting the HCSF program and is now sent monthly to participating HCSF families. Community-wide recruitment was also conducted in all four communities via mass media and community advertisements at places of employment, WIC days, and health care centers.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria and screening

To be eligible for inclusion, children had to: (1) be between the ages of 2 and 5 years; (2) live with at least one primary caregiver in a home setting; (3) be free of any major physical or behavioral disorder that would seriously impact participation; and (4) be willing to accept the 50% chance of randomization to a home visit group. Primary caregivers had to be willing to participate in home-based lessons, to attend group sessions, to complete questionnaires, to undergo physical and laboratory screening, and to have their child undergo basic physical screening. Exclusion criteria were minimal because of the communities’ value for inclusion in community programs and were thus limited to the presence of major physical or behavioral conditions that would preclude participation.

Randomization

Randomization at the family level was done after obtaining consent from and completing baseline measurements on participating families. Families were stratified at each tribal community on the basis of child BMI percentile for age and gender, with two strata at each community: families with children BMIs < 85th percentile and families with children BMIs ≥ 85th percentile. Within each stratum, half of the families were randomly assigned to the intervention condition and half to the control condition. Furthermore, within each stratum, a blocked randomization strategy was used to ensure that there was an equal number of families in the intervention and control groups. Stratified randomization at the family level was chosen to allow for differences between tribal communities and to balance families with overweight children (BMI ≥ 85th percentile) and families with optimal weight children (BMI < 85th percentile) between the intervention and control groups. Sample size was calculated using change in child BMI z-score as the primary outcome measure. A recruitment goal of 150 adult–child pairs was set in order to retain 120 families. Figure 2 illustrates the overall design and randomization of the HCSF project. Randomization at the family level, rather than at the community level, was chosen by the research team because no community wished to serve as a control, and all communities wished to receive the intervention.

Fig. 2.

Overall design and randomization scheme for Healthy Children, Strong Families

Tool Kit Curriculum

Tool kit lessons and activities were developed by the University of Wisconsin–Madison and Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Council research team and University of Wisconsin Extension specialists. Tool kit lessons were also peer-reviewed by AI community collaborators and AI home mentors with specific attention to cultural and social relevance of the lesson materials, activities, goals, and incentives. Each lesson targeted one of four healthy lifestyle behavioral changes: (1) increasing fruit and vegetable intake; (2) decreasing soda/sweetened drinks and candy intake; (3) increasing physical activity; and (4) decreasing TV viewing time.

Tool kit–type lessons have been successful in bringing about behavioral changes in other lifestyle intervention projects (Flynn et al., 2006; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group, 1999; Williams et al., 2004), and each lesson included goal setting and review, interactive delivery of information and skills, self-monitoring, and reinforcement. Lastly, each lesson emphasized balancing traditional and new AI patterns of diet and physical activity. Details of the HCSF curriculum development have been described previously (LaRowe et al., 2007).

Mentor Training

Mentors were tribal members or other individuals connected to the tribe and included experienced parents, grandparents, and respected community members who were capable of delivering the intervention according to study protocol. Mentors were trained extensively by the University of Wisconsin Extension staff, tribal wellness staff (including nurses, diabetes educators, and dietitians), knowledgeable tribal elders, and HCSF research staff. This training was adapted from a well-developed home-visiting training program, Healthy Families America (Prevent Child Abuse America, 2008), to encompass the needs of the HCSF intervention and objectives. Additional training was provided on child development, nutrition, and physical activity. Mentors received a full protocol manual, yearly training, and refresher sessions. In addition, the University of Wisconsin–Madison and Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Council project coordinators worked with mentors, discussing issues with in-home visiting and families’ lack of progress, and assessed mentor progress.

Mentors completed an activity form after each home visit documenting family members in attendance, lessons covered, time spent on lesson delivery, specific sections of each lesson covered, mentor’s assessment of the family’s interest in the lesson, and the family’s progress at setting new goals and meeting goals from the last visit.

Mentor Process Evaluation

Mentor process measures included self-report questions on comfort with home visitation and mentoring ability (pre- and post-training), knowledge and beliefs about nutrition and physical activity, and documentation of successes and challenges of intervention delivery. Mentors also received home-visiting supervision counseling, both one-on-one with the HCSF project coordinator and in a group setting with other mentors. Supervision provides support and feedback for the mentors and is a critical element (Keim, 2000) for improving home-visiting skills as well as staff retention.

Design Overview

Intervention group: Year 1 home visits and group sessions

During Year 1, mentors visited intervention families to deliver a family-based tool kit in 12 home visits. Mentors educated and coached children and primary caregivers on the four project goals relating to nutrition and physical activity. Tool kits included educational lessons concerning these goals. Each lesson included incentives related to the lesson’s theme, including culturally appropriate books, cooking utensils, pedometers, games, etc. Efforts were made to ensure mentor continuity in order to maintain a strong family–mentor bond, e.g., scheduling home visits around vacations, rescheduling the visit if the child was sick.

Mentors were assigned to a family by one of the HCSF program coordinators, who carefully considered factors that could impact relationship-building such as family connections, community connections, and children’s age. Initial contact with the family was made by phone, and mentors were encouraged to share information in order to create a friendly and supportive relationship. The first in-person lesson was designed to create dialogue between the mentor and the family and to begin building a supportive rapport. During each visit, mentors reviewed the lesson with the primary caregiver and child, led discussions and activities to help the caregiver and child learn about the topic, considered behavior change related to the topic, and assisted the family in setting goals to attempt behavior change. Ideally, mentor-led discussions assisted the primary caregiver and child in progressing along the continuum of motivation toward actual behavior change, while helping the primary caregiver build skills and confidence in his or her own ability to adopt healthier lifestyle choices.

During Year 1, intervention families were also invited with their extended family to three mentor-led group sessions. These group sessions helped intervention families enlist the support of their extended family in making and sustaining healthy lifestyle choices. Topics included nutrition information, hands-on cooking, and group physical activities such as walking, Frisbee golf, bike rides, and participation in local fitness events.

Intervention group: Year 2 group sessions

During Year 2, intervention families participated in monthly group meetings and continued to receive a monthly newsletter with parenting tips/recipes/local program notices to help in sustaining behavior changes implemented in Year 1. Monthly group meetings focused on topics such as basic nutrition concepts (sugar, fats, appropriate serving sizes, food choice variety) and ideas for physical activities. Group meetings included a healthy family meal, separate adult and child sessions, and a prize drawing for adults with small incentives for children attending. Some of these meetings were incorporated into community events (e.g., diabetes fundraiser walk).

Control group: education only

During Year 1, control families received educational tool kits and incentives sent home on the same cycle as intervention families, but they did not receive any mentoring. During Year 2, control families received only the monthly newsletter.

Incentives

Participant incentives were chosen with input from tribal wellness teams and included gift cards to local merchants for baseline and post-intervention measures. Incentive amounts varied based on individual participation in data collection, but averaged $175. Lesson-specific incentives included an HCSF calendar to track goals and progress, cooking utensils, and physical activity items such as balls, Frisbees, pedometers, exercise videos, etc.

Outcome Measures

The Table lists the adult and child study measures collected at baseline, 1 year post-intervention, and 2 years post-intervention. Child BMI z-score change between baseline and post-intervention is the primary outcome measure. A second primary outcome measure is change in adult BMI. Secondary outcome measures for both children and adult primary caregivers include nutrition and physical activity behavior measures. Additional psychosocial measures were also obtained in adult primary caregivers. Adult biochemical measures were obtained in a subset of families.

Anthropometrics

Height was measured with a portable stadiometer to the nearest 0.1 cm. Weight was measured with a calibrated electronic scale (Tanita Corporation of America, Inc., Arlington Heights, IL) without shoes and in light clothing to the nearest 0.1 kg. Children heights and weights were converted to BMI percentiles using CDC parameters. Adult height and weight were used to calculate BMI. Waist circumference was measured at the iliac crest with a flexible plastic measuring tape to the nearest 0.1 cm.

Diet and nutrition

Diets were assessed in adult primary caregiver and child by 24-hour dietary recalls (24HR). Three 24HR were obtained on non-consecutive days (including one weekend day) by trained study personnel. For participating children, 24HR were obtained via proxies (primary caregiver and Head Start teacher). Servings per day of fruit/vegetables and of soda/sweetened drinks and candy for each child and adult primary caregiver were quantified through analysis using the Nutrition Data System for Research (NDSR) (database version 2005, Nutrition Coordinating Center, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN). 24HR have been shown to give valid and reliable measurements of dietary intake in individuals (Mullenbach et al., 1992) and in preschool children when estimation is obtained from a parent/primary caregiver (Baranowski et al.,1991; Reilly et al., 2001). A subset of families completed the Block Food Questionnaire (Block Kids: 2–7) at baseline, and all families completed the Block Food Questionnaire at the post-intervention visit.

TV and screen time

Screen time was assessed at the same time as dietary recalls by the inclusion of 4 questions asking how much time the TV was on in the home on the day of recall; how much time the child or primary caregiver spent watching TV (including videos/DVDs); and how much time the child spent playing video games or using a computer (screen time) during the previous 24 hours.

Physical activity

Physical activity in children and adult primary caregivers was measured using Actical accelerometers (Mini Mitter, Bend, OR) worn on the hip for a period of 7 days with a minimum of 5 days (10 hours/day) required for accurate data collection. Accelerometry has been shown to be a valid, objective method for monitoring physical activity in preschool-age children (Jackson et al., 2003; McIver et al., 2004) and in adults (Chen & Bassett, 2005). Based on our preliminary studies, 5 days will allow detection of relative changes in average activity level expected from the intervention.

Biochemical measures

Laboratory measures were conducted on a subset of adult primary caregivers. Measures of glucose tolerance were done using a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), with fasting blood sugars obtained on pregnant primary caregivers. Other measures obtained were fasting blood lipid profile, and C-reactive protein, urinary microalbumin, and creatinine levels. Subjects were notified of their test results, and those with abnormal results referred for medical follow-up.

Questionnaire measures

Three questionnaires were completed by adult primary caregivers:

Health Behavior Efficacy is a 20-item questionnaire that yields scores on dimensions of self-efficacy to perform health-related behaviors, including nutrition and physical activity, plus intentions, attitudes, and subjective norms towards healthy behaviors. The questionnaire was developed using previous scales based on health behavior change theories (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995; Schwarzer & Renner, 2005; Armitage, 2005) relevant to the study intervention techniques plus input from university and tribal research personnel.

The SF-12v2 Health Survey (Ware et al., 2005) is a widely used 12-item instrument for assessing self-perceived health-related quality of life. It produces two composite scores, Physical Component and Mental Component, and comprises eight scale scores: physical functioning, physical role, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, role emotional, and general mental health.

The Cultural Involvement Scale is a 20-item measure specific to AI populations that yields a general score for involvement in AI culture relating to attitudes and behaviors (Malcarne et al., 2006; Zimmerman et al., 1996). This measure was administered at baseline only.

Statistical Analyses

The effectiveness of the HCSF intervention will be determined by testing two sequential primary hypotheses and by examining numerous secondary outcome measures. Our first primary hypothesis is that children receiving mentored home visits plus group visits will have a decrease in mean BMI z-scores relative to children in the non–home-visit group. Our second primary hypothesis is that primary caregivers in the home-visit group will have decreases in mean BMI relative to primary caregivers in the non–home-visit group.

Secondary hypotheses will examine if children and primary caregivers receiving mentored home visits show improvements in health-related behaviors (fruit/vegetable consumption, soda/sweetened drink and candy consumption, hours of TV viewing, physical activity) relative to those in the non–home-visit group. They will also examine if primary caregivers receiving mentored home visits plus group visits have improvements in mean levels of biochemical markers relative to primary caregivers in the non–home-visit group. In addition, positive changes in health behavior efficacy and health-related quality of life (measured via questionnaire) as a result of the intervention will be examined. In doing this, scores on the Cultural Involvement Scale will be used as covariates since it is possible that involvement in AI culture interacts with attitudes toward health-related quality of life and health efficacy.

Analysis plan

Primary hypotheses will be tested using 2 × 2 mixed ANOVA with time point and home-visit condition being the two factors, the time point × home-visit condition interaction being the test of interest. Overall alpha for each ANOVA will be .05, as each tests a different hypothesis using a different subject group. Secondary hypotheses will be tested using multivariate procedures since it is likely that these dependent variables will be correlated. Alpha levels will be set at .05 for each multivariate test.

Cost-effectiveness and Cost-benefit

Once research and evaluation-specific costs are removed, the unit cost per family is expected to be about $700. In addition to the statistical analysis described above, (1) the overall and unit costs based on expenditures for both intervention and control families will be confirmed; and (2) cost-effectiveness will be determined by dividing the total cost for all families by the number of families attaining improved scores on the key outcome indicators at the time of the final follow-up measures, for both intervention and control groups.

Conclusions

HCSF is a multi-site, 2-year, family-based randomized controlled trial of a culturally appropriate home-mentoring intervention for 2–5-year-old AI children and their primary caregivers. The trial will examine the impact of mentor-delivered educational tool kits and group visits versus mailed educational tool kits only on obesity and nutrition and physical activity behaviors in AI children and their primary caregivers. HCSF aims to change behaviors not only through increased knowledge of healthy lifestyles but also through enhanced parenting skills and self-efficacy. It was designed using a unique participatory approach by the communities and academic partners and is based both on local data and cultural norms/practices, as well as theory. The study design, rationale, and methods have been described in this article.

The following are key aspects of the HCSF study that make important contributions to the field and are thus useful to other researchers and practitioners: (1) it is the first multi-site randomized controlled trial of home visiting for healthy lifestyle changes conducted in AI families; (2) it is the first community trial to address multiple lifestyle factors in both parent and child; (3) the intervention is delivered by trained local mentors; (4) the trial was designed using a CBPR process such that community leaders, wellness staff, and community members had input into curriculum design, randomization, modes of recruitment, and group sessions, and will be involved in results analysis and dissemination; (5) it involved the development of a unique curriculum that may be used with or without a home mentor; (6) it includes group sessions that incorporated community events at each site; (7) it examines multiple measures including measures of adult self-efficacy and cultural involvement to assess how these factors may affect behavior change; (8) it is the first large-scale use of accelerometry in AI preschool children to assess physical activity; (9) it involved community members in producing materials such as a cookbook and local resource guides for families; and (10) it is part of a larger long-term CBPR academic–tribal partnership designed to assist AI communities in moving toward both individual and environmental changes to facilitate healthy lifestyles and prevent obesity-related diseases.

Limitations include the difficulty in retaining families for 2 years, differences between implementation sites with respect to longevity and implementation fidelity of mentors, other complementary community-prevention programs, and tailoring of the intervention to individual family needs by mentors. A major strength and weakness of the study is the communities’ decision to randomize by family and not by site. While this is advantageous for the sites, as all communities were able to receive the intervention, it may have caused contamination as these are small communities and a true control status is difficult to achieve. Due to the presence of the study in the communities, awareness of child nutrition and physical activity needs was heightened. Further, simultaneous environmental interventions which would serve to strengthen the ability of families to make healthy choices due to the family randomization strategy were not utilized. However, community-based environmental interventions are now under way.

Our current research project builds on the premise that obesity prevention should be targeted in early childhood, based on our prior research in Wisconsin AI children (Adams et al., 2008). HCSF utilizes the family environment as the unit for obesity prevention and lifestyle change efforts, which may be essential in addressing family values and perceptions, role modeling, and overcoming barriers (Burnet et al., 2002; Golan & Crow, 2004; St. Jeor et al., 2002). Utilizing community-based mentors to engage families increases the relevance and acceptance of the intervention to community members and improves the self-efficacy of parents to model healthy behaviors and to assist their children in appropriate eating and physical activity. The family-based approach as well as the strong community input into the HCSF project increases its potential for community sustainability as well as it generalizability to similar communities.

Table.

Healthy Children, Strong Families baseline and 1- and 2-year post-intervention outcome measures

| Child | Primary Caregiver | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Baseline | 1 yr post | 2 yrs post | Baseline | 1 yr post | 2 yrs post |

| Anthropometric | ||||||

| Waist circumference | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Height and weight | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| BMI | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Biochemical* | ||||||

| Glucose tolerance | ● | ● | ||||

| Blood lipid profile | ● | ● | ||||

| C-reactive protein level | ● | ● | ||||

| Urine microalbumin level | ● | ● | ||||

| Creatinine level | ● | ● | ||||

| Nutrition & physical activity behaviors | ||||||

| Fruit and vegetable servings/day 24HR/FFQ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Soda/sweetened drink and candy servings/day 24HR/FFQ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Hours physical activity/day | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Hours TV viewing time/day | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Accelerometry (5 days) | ● | ● | ||||

| Psychosocial questionnaires | ||||||

| Health Behavioral Efficacy | ● | ● | ||||

| SF-12v2 Health Survey | ● | ● | ||||

| Cultural Involvement Scale | ● | |||||

BMI = body mass index; 24HR = 24-hour dietary recall; FFQ = food frequency questionnaire.

Biomarkers were obtained in a subset of adult primary caregivers.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a cooperative agreement between the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (U-01 HL087381) and the University of Wisconsin. Additional support was provided by the Wisconsin Partnership Program and the Oneida Nation. We are grateful to the tribal governments of the following communities for supporting this work: the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, the Menominee Nation, and the Oneida Nation.

The following key staff and community members assisted the study team and provided advice on ways to implement the study in their communities:

Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Council: SuAnne Vannatter and Nancy Miller-Korth.

Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians: Mary BigBoy, LuAnn Wiggins, Charlie Wiggins, Mark LeCapitaine, Lori Gregorie, Anne Rosin, Sandy Kolodziejski, and Lin Lemieux.

Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians: Randy Samuelson, Sue Wolfe, Anita Dionne, Heather Fortin, Hope Williams, Kathy Kinny, Jeanne Wolfe, Stacy Stone, Carol Cardinal, Denise Rheume, Betty Batiste, and Mary White.

Menominee Nation: Jerry Waukau, Mark Caskey, Scott Krueger, Michael Skenadore, Dave Hoffman, Brenda Hoffman, Jean Cox, Jeanette Perez, Sue Blodgett, Mary Waukau, Bethany Miller, and Mary Lawe.

Oneida Nation: Eric Krawczyk, Tina Jacobsen, Dawn Krines Glatt, Jill Caelwaerts, Monique Gore, Susan Higgs, Karla Jenquin, Jenny Jorgensen, Charlene Kizior, and Michelle Mielke.

University of Wisconsin–Green Bay: Joelle Frank and Stephanie Jansen.

University of Wisconsin School of Medicine: Heather Lukolyo.

References

- Adams AK, Prince RJ. Correlates of physical activity in young American Indian Children: Lessons learned from the Wisconsin Nutrition and Growth Study. Journal of Public Health Management Practice. 2010;16:394–400. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181da41de. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams AK, Harvey H, Brown D. Constructs of health and environment inform child obesity prevention in American Indian communities. Obesity. 2008;16:311–317. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams AK, Miller-Korth N, Brown D. Learning to work together: Developing academic and community research partnerships. Wisconsin Medical Journal. 2004;103:15–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams AK, Quinn RA, Prince RJ. Low recognition of childhood overweight and disease risk among Native-American caregivers. Obesity Research. 2005;13:146–152. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage CJ. Can the theory of planned behavior predict the maintenance of physical activity? Health Psychology. 2005;24:235–245. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior. 2004;31:143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranowski T, Sprague D, Baranowski JH, Harrison JA. Accuracy of maternal dietary recall for preschool children. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1991;91:669–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnet D, Plaut A, Courtney R, Chin MH. A practical model for preventing type 2 diabetes in minority youth. Diabetes Educator. 2002;28:779–795. doi: 10.1177/014572170202800519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Obesity prevalence among low-income, preschool-aged children—United States, 1998–2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2009;58:769–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KY, Bassett DR., Jr The technology of accelerometry-based activity monitors: Current and future. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2005;37(11 Suppl):S490–S500. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185571.49104.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program. Design and methods for a clinical trial in the prevention of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:623–634. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.4.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond JE, Weir AE, Kysela GM. Home visitation practice: Models, documentation, and evaluation. Public Health Nursing. 2002;19:21–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2002.19004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH. Family-based behavioural intervention for obese children. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 1996;20(Suppl 1):S14–S21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn MA, McNeil DA, Maloff B, Mutasingwa D, Wu M, Ford C, et al. Reducing obesity and related chronic disease risk in children and youth: A synthesis of evidence with ‘best practice’ recommendations. Obesity Reviews. 2006;7(Suppl 1):7–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golan M, Crow S. Parents are key players in the prevention and treatment of weight-related problems. Nutrition Reviews. 2004;62:39–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golan M, Weizman A, Apter A, Fainaru M. Parents as the exclusive agents of change in the treatment of childhood obesity. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1998;67:1130–1135. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.6.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Great Lakes EpiCenter. Community health data profile: Minnesota, Wisconsin & Michigan tribal communities. Lac du Flambeau, WI: Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Council, Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DM, Reilly JJ, Kelly LA, Montgomery C, Grant S, Paton JY. Objectively measured physical activity in a representative sample of 3- to 4-year-old children. Obesity Research. 2003;11:420–425. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keim A. Finding and supporting the best: Using the insights of home visitors and consumers in hiring, training, and supervision. Zero to Three. 2000;21:37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Koplan JP, Liverman CT, Kraak VA. Preventing childhood obesity: Health in the balance. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRowe TL, Wubben DP, Cronin KA, Vannattter SM, Adams AK. Development of a culturally appropriate, home-based nutrition and physical activity curriculum for Wisconsin American Indian families. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2007;4:A109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay AC, Sussner KM, Kim J, Gortmaker S. The role of parents in preventing childhood obesity. Future Child. 2006;16:169–186. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay RS, Cook V, Hanson RL, Salbe AD, Tataranni A, Knowler WC. Early excess weight gain of children in the Pima Indian population. Pediatrics. 2002;109:E33. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.2.e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcarne VL, Chavira DA, Fernandez S, Liu PJ. The scale of ethnic experience: Development and psychometric properties. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2006;86:150–161. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8602_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIver PK, Almeida J, Dowda M, Pate R. Validity of the ActiGraph and Actical accelerometers in 3–5 year-old children. Paper presented at the North American Society for Pediatric Exercise Medicine; New Brunswick, Canada: St. Andrews; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton DB. Nurse home visits to maternal-child clients: A review of intervention research. Public Health Nursing. 2004;21:207–219. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2004.021303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullenbach V, Kushi LH, Jacobson C, Gomez-Marin O, Prineas RJ, Roth-Yousey L, Sinaiko AR. Comparison of 3-day food record and 24-hour recall by telephone for dietary evaluation in adolescents. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1992;92:743–745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Prevalence of overweight among children and adolescents: United States, 1999. Hyattsville, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Polhamus B, Dalenius K, Borland E, Mackintosh H, Smith B, Grummer-Strawn L. Pediatric Nutrition Surveillance 2007 Report. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Prevent Child Abuse America. Healthy Families America. 2003–2012 Retrieved September, 22, 2005, from http://www.healthyfamiliesamerica.org/home/index.shtml.

- Reilly JJ, Montgomery C, Jackson D, MacRitchie J, Armstrong J. Energy intake by multiple pass 24 h recall and total energy expenditure: A comparison in a representative sample of 3–4-year-olds. British Journal of Nutrition. 2001;86:601–605. doi: 10.1079/bjn2001449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salbe AD, Weyer C, Lindsay RS, Ravussin E, Tataranni PA. Assessing risk factors for obesity between childhood and adolescence: I. Birth weight, childhood adiposity, parental obesity, insulin, and leptin. Pediatrics. 2002;110:299–306. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M. Generalized self-efficacy scale. In: Weinman J, Wright S, Johnston M, editors. Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Windsor, England: NFER-NELSON; 1995. pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, Renner B. Health-specific self-efficacy scales. Retrieved Oct 15, 2005 from http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~health/healself.pdf.

- St Jeor ST, Perumean-Chaney S, Sigman-Grant M, Williams C, Foreyt J. Family-based interventions for the treatment of childhood obesity. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2002;102:640–644. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90146-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinki M, Turner-Bowker DM, Gandek B QualityMetric Incorporated, & New England Medical Center Hospital. Health Assessment Lab. How to score Version 2 of the SF-12 Health Survey (with a supplement documenting Version 1) Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Inc; Boston, MA: Health Assessment Lab; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Williams K, Prevost AT, Griffin S, Hardeman W, Hollingworth W, Spiegelhalter D, Kinmonth AL. The ProActive trial protocol - a randomised controlled trial of the efficacy of a family-based, domiciliary intervention programme to increase physical activity among individuals at high risk of diabetes [ISRCTN61323766] BMC Public Health. 2004;4:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worobey J, Pisuk J, Decker K. Diet and behavior in at-risk children: Evaluation of an early intervention program. Public Health Nursing. 2004;21:122–127. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2004.021205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrotniak BH, Epstein LH, Paluch RA, Roemmich JN. Parent weight change as a predictor of child weight change in family-based behavioral obesity treatment. Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158:342–347. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.4.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MA, Ramirez-Valles J, Washienko KM, Walter B, Dyer S. The development of a measure of enculturation for Native American youth. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1996;24:295–310. doi: 10.1007/BF02510403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]