Abstract

In this work, we introduce Forcefield_PTM, a set of AMBER forcefield parameters consistent with ff03 for 32 common post-translational modifications. Partial charges were calculated through ab initio calculations and a two-stage RESP-fitting procedure in an ether-like implicit solvent environment. The charges were found to be generally consistent with others previously reported for phosphorylated amino acids, and trimethyllysine, using different parameterization methods. Pairs of modified and their corresponding unmodified structures were curated from the PDB for both single and multiple modifications. Background structural similarity was assessed in the context of secondary and tertiary structures from the global dataset. Next, the charges derived for Forcefield_PTM were tested on a macroscopic scale using unrestrained all-atom Langevin molecular dynamics simulations in AMBER for 34 (17 pairs of modified/unmodified) systems in implicit solvent. Assessment was performed in the context of secondary structure preservation, stability in energies, and correlations between the modified and unmodified structure trajectories on the aggregate. As an illustration of their utility, the parameters were used to compare the structural stability of the phosphorylated and dephosphorylated forms of OdhI. Microscopic comparisons between quantum and AMBER single point energies along key χ torsions on several PTMs were performed and corrections to improve their agreement in terms of mean squared errors and squared correlation coefficients were parameterized. This forcefield for post-translational modifications in condensed-phase simulations can be applied to a number of biologically relevant and timely applications including protein structure prediction, protein and peptide design, docking, and to study the effect of PTMs on folding and dynamics. We make the derived parameters and an associated interactive webtool capable of performing post-translational modifications on proteins using Forcefield_PTM available at http://selene.princeton.edu/FFPTM.

Keywords: forcefield, post-translational modifications, AMBER, partial charges, ff03

1 Introduction

Almost all advances in protein structure prediction and de novo protein design from computational approaches treat amino acids as unmodified.1-23 As pointed out in a recent review,24 there has been relatively little work done developing computational methods for protein structure modeling with amino acids that may exhibit unnatural amino acids or post-translational modifications (PTMs). Many developed computational approaches explicitly rely on the accuracy of different forcefields to be able to model and design systems of interest. PTMs are the covalent modifications of a protein during or after its translation, and have wide effects broadening its range of functionality. Proteins can be post-translationally modified biochemically by enzymes, or chemically by a process such as reductive methylation. As a control mechanism, PTMs can activate/silence transcription and thus tightly regulate gene expression, recruit proteins with PTM-specific binding domains,25 block proteins from binding,26 participate in signaling cascades,27 and change the charge and architecture of various large protein constructs such as the nucleosome.28 Whereas mutations can only occur once per position, different forms of post-translational modifications may occur in tandem.29-31 For example, histone H3, one of the most modified proteins in humans, can be covalently modified with different PTMs at the same residue position, or simultaneously at other sites. These are controlled by the specificity of the post-translationally modifying enzymes for their protein substrates and the regioselectivity and sequence selectivity of the side chains modified.31 The modifications themselves can occur in different locations, both inside and outside of the cell, as well as intramembrane.

PTMs are ubiquitous in nature. As of June 2013, there were 80,688 instances of PTMs identified experimentally32 on 540,261 proteins, as annotated in the Swiss-Prot database.33 PTMs can occur homogeneously or heterogeneously a single time or multiple times on a single sequence, so the number of instances provides an upper bound on the number of sequences containing modifications. There are over 450 modification types annotated in the database. The Protein Data Bank (PDB),34 a central repository for solved protein structures, contains over 90,000 structures. According to the PSI-MOD protein modification browser as of April 2012, there are approximately 26,000 instances of modified amino acids in the PDB. This number includes 15,573 instances of disulfide-bridges. Removing PDB IDs containing disulfide-bridges, approximately 2000 structures contain a single PTM and about half as many contain multiple modifications (see section Characterization of Background Structural Similarity Between Modified/Unmodified Structures and Distribution of PTM Density Contained in the PDB).

PTMs can affect the microenvironment of the protein, and can have a notable effect redistributing conformers. They may expand the catalytic capacity of modified proteins, can tune regulation, and can change the subcellular address of a protein. This can be done by marking it for degradation, sending a protein from the cell membrane to the trans-golgi network, and signalling extra-cellular transport.31 The role of PTMs in affecting protein structure is not well understood though, as often before structure determination, PTMs are removed to mitigate sample heterogeneity. Thus, there is much left to learn about the effects of modifications at an atomistic level. To understand these interactions, we need to be able to generate detailed atomistic models using a forcefield to address proteins containing PTMs.

Current methods in protein structure prediction and de novo protein design have difficulty in modeling these structures as there are few parameters available to describe the modified amino acids. The AMBER forcefield35 has a potential energy whose functional form is similar to other forcefields such as CHARMM,36 DREIDING,37 GROMOS,38 OPLS-AA,39 and ECEPP,40 with parameters derived independently in each. Atomic charges and parameters for AMBER41 are available for phosphoserine, phosphothreonine, phosphotyrosine, phosphohistidine,42-44 S-nitrosocysteine,45 and trimethyllysine.46,47 They have already been used to study the induction of conformational changes as a result of the large local negative charge phosphorylation adds,48 the competition between hydrogen bonds and solvation in phosphopeptides,49 and the effect of dimethylation and acetylation on histone tails.50 Efforts have very recently been reported to revise the AMBER parameters for phosphorylated amino acids44 using thermodynamic cycles. The GLYCAM forcefield51 can address the modeling of glycosylated proteins. In the CHARMM52 forcefield, there have been parameters derived for methylated lysine (Kme1, Kme2, Kme3), acetylated lysine (Kac), as well as methylated arginine (Rme1, Rme2).53 Recently parameters were also presented for non-natural side-chains compatible with CHARMM and GROMACS.54 Several noncanonical amino acid (NCAA) parameters were recently introduced into the Rosetta suite of tools, leading to designs that improved binding of calpastatin-derived peptides to calpain-1 using NCAA substitutions.55 The incorporation of these new parameters allows for increased design space, but the lack of quantum-chemically derived electrostatic parameters presents potential drawbacks.

AMBER forcefields for the natural amino acids were originally developed (ff86),56 reparameterized (ff94),41 and revised57 (ff99). The charges in ff99 were identical to that in ff94, which used HF/6-31G*//HF/6-31G* RESP for the charge fitting procedure, with backbone atom charges for positive, negative, neutral, and proline residues fixed to values for each of the aforementioned groups. ff94 was further revised after the observation that it overstabilized α-helixes, yielding ff99SB.58 ff03 is a third generation forcefield that calculated the partial atomic charges using the B3LYP/cc-pVTZ//HF/6-31G** method without fixing backbone partial charges and is derived in an organic solvent to mimic the dielectric environment of the interior of a protein.59 Although employing fundamentally different procedures for partial charge derivation, it was reported that ff03 and ff99SB behave most similarly among the AMBER forcefields.58

AMBER ff0359 has been used widely for a number of different applications including to characterize the rate-limiting step of Trp-cage folding,60 to fold alanine-based helical peptides,61 to aid in understanding the isoform selectivity of chrysin using binding free energy calculations,62 and with further optimization to score and refine protein models relative to the native.63,64 Similarly, ff99SB has also been applied to different applications including structure generation, structure refinement after homology modeling,65 calculation of binding free energies,66 studies of protein folding,67 conformational changes mediated by other biological molecules,68 and understanding motions over different timescales.69

In this work, we present a new set of self-consistent parameters for 32 post-translational modifications designed to work with AMBER ff03. We subsequently test them on a macroscopic scale using all-atom molecular dynamics simulations on a representative set of pairs of modified and unmodified protein structures. The selected PTMs were based on those found to be among those most abundantly observed in nature as shown in our previous work.32 On a microscopic scale, we perform comparisons of the ab initio and AMBER torsion energy landscape for several key χ angles on the PTMs which could benefit from corrections, and subsequently calculate corrections to improve the agreement between the ab initio and AMBER relative energies. We present the validated parameters with instructions for use, and a complementary webtool (http://selene.princeton.edu/FFPTM) so that the broader academic community can make use of the parameter set. With a forcefield capable of modeling post-translationally modified amino acids, we would be able to sample uncharted conformational and design space and further our understanding of the proteome, modificome, and interactome at an atomistic level.

2 Methods

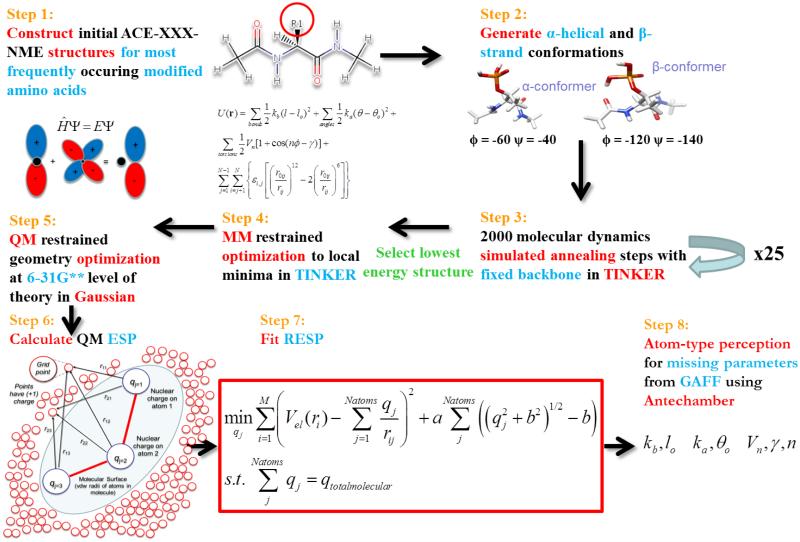

2.1 Procedure for Derivation of Partial Charges in FF_PTM

Calculations consistent with the AMBER forcefield ff03 were derived following the general procedure of Duan et al.59 This was completed for 32 post-translationally modified amino acids. The choices for PTMs to be parameterized were primarily based on those found to be most frequently occurring in nature32 that have not been parameterized in the literature. Backbone charges were not fixed across post-translational modifications. This was done for four reasons. First, constraining the backbone charges to specific values during the charge parameter optimization may reduce the quality of fit. Second, this is consistent with the procedure of Duan et al.59 Third, the derivatization of the canonical amino acids may lead to non-canonical variants which may be di-substituted; thus, using a consistent set of backbone charge parameters would not be valid in that case as it would not be expected that the backbone charge distribution be the same for an amino acid with one or two R-groups attached to the Cα or a substitution such as methylation on the backbone nitrogen. Fourth, the consensus backbone charges derived for ff94 were done only in the context of the 20 natural amino acids. It would be expected that adding additional atoms and electrons to the side-chains would change the electron cloud distribution to be different from that in the consensus charges derived based on the natural amino acids. The Cα atoms would be especially expected to deviate due to the addition of new atoms. The overall methodology of the parameterization framework is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Framework for initial forcefield parameterization of the post-translationally modified amino acids.

In Step 1, initial structures for each modified amino acid dipeptide were manually built using MarvinSketch.70 Dipeptides constructed were of the amino acid, preceded by an acetyl, and followed by an N-methyl group (ACE-XXX-NME). The L- form of each amino acid was constructed unless otherwise noted, employing the CORN rule. This was done to mimic the amino acid in the environment of a protein backbone. In Step 2, initial structures were each modified using the distance geometry (distgeom) routine of the TINKER 5.1 package71 in order to generate α-helix (ϕ = −60, ψ = −40) and β-strand (ϕ = −120, ψ = −140) conformers. Using TINKER and the AMBER ff9441 parameter set, while maintaining restraints on the main-chain torsion angles, each conformer was subjected to 25 molecular dynamics simulated annealing calculations (using the anneal routine with default parameters) in Step 3. Here, AMBER ff94 was used to generate initial feasible points. The initial and final temperatures used for annealing were 1000K and 0K, respectively. 2000 cooling steps were performed in each simulation, with a linear cooling protocol and with a 1 femtosecond timestep. Any missing force constants and equilibrium parameters were added to the TINKER amber_ff94 parameter set by manually inputting suitable parameters of similar atom types from GAFF72 for the purpose of generating initial conformations. The lowest energy structure for each conformer was next minimized to the nearest local minima using the optimize routine in Step 4, with a rms gradient cutoff of 0.01. The resulting conformers were optimized (Step 5) using Gaussian0973 at the HF/6-31G** level of QM theory while keeping the ϕ and ψ angles fixed. 6-31G is a split valence basis set that has two sizes of basis functions for each valence orbital. Split valence basis sets allow orbitals to change size, but not shape. Polarized basis functions remove this restriction by adding orbitals with angular momentum beyond what is necessary for the ground state. 6-31G** (or 6-31G(d,p)) adds p-orbital functions to hydrogen atoms, as well as d-orbital functions to heavy atoms.74 The optimized α-helical and β-strand conformers are both depicted in Supporting Information section Images of Each Parameterized Post-Translational Modification Grouped by Scaffold Residue.

In Step 6, single-point energy calculations were carried out on the optimized dipeptide structures using the density functional theory (DFT) method and the B3LYP exchange and correlation functionals75-77 and the cc-pVTZ78 basis set. The IEFPCM implicit solvent model79,80 was applied to mimic the protein interior using an organic solvent environment as suggested by Duan et al.59 (ε = 4) and to avert overpolarization. The quantum mechanically calculated electrostatic potential (ESP) was determined at each point defining the molecular surface in the solvent-accessible region around the optimized structure at 1.4, 1.6, 1.8, and 2.0 times the vdw radii using the program DMS with a density of 0.5, producing 2.5-2.8 points/Å2.81 The calculated ESP values from both the helical and strand conformers were next used to perform a two-stage RESP fit of the partial atomic charges using the Antechamber suite of the Amber-Tools 1.4 package.82 Thus, the charge parameters were derived to be compatible for simulations of protein and peptides in the condensed-phase rather than the gas phase. This procedure was completed for each of the 32 PTMs.

2.2 Procedure for Derivation of Missing Bond, Angle, and Dihedral Angle Parameters

One principle in forcefield parameterization of new molecules is to use analogy when possible. Guided by this principle, in Step 8 of the procedure, missing bond, angle, and dihedral parameters were perceived by matching atom types either automatically82 or manually from the GAFF forcefield.72 The Lennard-Jones parameters for every atom type were taken to match exactly those contained in ff03. A similar approach was done when the GAFF forcefield was constructed72 and thus we believe they can be reasonably transferred as parameters for the modified amino acids since these parameters are a function of the atom type. Missing bond parameters were borrowed from GAFF, which derived their parameters for experimental equilibrium bond lengths req using the AMBER protein forcefields, ab initio calculations (MP2/6-31G*), and crystal structures. The authors noted that most of the experimental data from which they derived their parameters comes from the mean values of req from X-ray and neutron diffraction.72,83,84 Similarly, missing angle bending parameters were derived from GAFF, whose initial parameterization was based on fitting to previous forcefields, MP2/6-31G* calculations, and experimental crystal data for bond angles and bond lengths.72,83 Finally, any missing torsion angle parameters were borrowed from GAFF. These force constants have been previously fitted to match an ab initio rotational profile. We note some of the moieties in the crystal structures tested in the GAFF paper72 overlap with some of the side-chains of the PTMs.

Care was taken to utilize parameters from GAFF only when they were not contained within ff03. To do this, the program tleap was called using an input script to attempt to create the input coordinate (inpcrd) and topology/parameter (prmtop) files for each post-translational modification using the parameters contained only within ff03. If tleap successfully completed, all of the bond, angle, torsion, and nonbonded parameters for the new molecule were contained in ff03 complemented by the partial charges calculated in this work. If tleap indicated that there were parameters missing and thus input coordinate and topology/parameter files could not be created, the program parmchk, contained in AmberTools11 was utilized. In our case, parmchk was used to extract the minimum number of suitable missing parameters from GAFF needed for calculations of a molecule that are not contained in ff03. After obtaining these parameters and adding them to unique forcefield modification (frcmod) files specific to each PTM, tleap was subsequently utilized to confirm that each post-translational modification can successfully generate the corresponding input coordinate and topology/parameter files. Since parameters specific to phosphoserine, phosphothreonine, and phosphotyrosine were previously developed,43 we adapted these parameters combined with GAFF parameters as reasonable approximations. It is noteworthy that in thirteen of the thirty-two molecules parameterized, no new bond, angle, or torsion parameters were needed to be borrowed from GAFF since ff03 already had defined the parameters for all of the atom types for the modified amino acid. This means that the only new parameters were the set of calculated partial charges for every atom in the system.

2.3 Simulation Procedure

Structures chosen for simulation were those for which parameters were made in FF_PTM and were those where the level of structural dissimilarity between the native modified and unmodified structure was low to allow for direct comparison of the simulations. A description of the procedure for which to resolve any missing residues in the input structures is provided in the Supporting Information section Homology Modeling Missing Residues in Pairs of Modified/Unmodified Proteins Curated. The new partial charge parameters derived were used to model the PTMs. Unrestrained all-atom molecular dynamics simulations were performed in AMBER11 for the 17 pairs out of the 40 pairs of modified/unmodified structures shown in Table 1 for which we can utilize FF_PTM, beginning with the “cleaned” structures containing homology-modeled Cα atoms in the cases of missing residues. The MD procedure employed and subsequent analysis was done identically for all pairs. All calculations were done using ff03 and the generalized Born implicit solvent model accessed with the igb=5 flag,85,86 and used a 16 Å non-bonded cutoff. First, the structures were minimized with 6000 steps of steepest descent followed by 4000 steps of conjugate gradient minimization. Next, the structures were heated in 6 stages in increments of 50K using Langevin dynamics with a collision frequency γ of 5 ps−1. Each stage consisted of heating and equilibration over 30 picoseconds using a 0.5 femtosecond timestep so as to gently heat the minimized structures to 300K. Shake constraints were applied to all bonds involving hydrogen to reduce the number of degrees of freedom. Next, each system underwent production for 5 ns using a 1 femtosecond time-step at a constant temperature of 300K, using Langevin dynamics. Potential energy, kinetic energy, Cα-RMSD to the minimized PDB structures, and backbone ϕ and ψ angles were tracked over the course of each simulation. These metrics represented changes in local secondary structure, energetic stability, and global tertiary structure, while being cognizant of the background levels of structural changes occurring as a result of the modification, presented elsewhere in this work.

Table 1.

Comparison of All Pairs of Modified and Unmodified PDB Structures Curated from the PDB for a Single Amino Acid, Single PTM

| Modified PDB |

Unmodified PDB |

Length of Protein/ Domain |

Sequence Position Modified |

Modification Type | Cα RMSD | Consensus Modified Secondary Structure |

Consensus Unmodified Secondary Structure |

Modification is Cause of Structural Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2IVT | 2IVS | 314 | 905 | O-PHOSPHOTYROSINE | 1.094 | Strand | Strand | |

| 3DK6 | 3DK3 | 293 | 393 | O-PHOSPHOTYROSINE | 0.495 | Strand | Strand | |

| 1U54 | 1U46 | 291 | 284 | O-PHOSPHOTYROSINE | 0.940 | Strand | Strand | |

| 1D4W | 1D4T | 11 | 281 | O-PHOSPHOTYROSINE | 0.233 | Strand | Strand | |

| 2QO7 | 2QO9 | 373 | 701 | O-PHOSPHOTYROSINE | 0.151 | Loop | Loop | |

| 2XKK | 2XKJ | 767 | 1124 | O-PHOSPHOTYROSINE | 4.263 | Loop | Loop | |

| 2KB3 | 2KB4 | 143 | 15 | PHOSPHOTHREONINE | 23.067 | Loop | Loop | X |

| 2JFM | 2J51 | 325 | 183 | PHOSPHOTHREONINE | 0.333 | Helix | Helix | |

| 3D5W | 3D5U | 317 | 196 | PHOSPHOTHREONINE | 0.810 | Loop | Loop | |

| 3CKX | 3CKW | 304 | 163 | PHOSPHOTHREONINE | 0.936 | Loop | *1 | |

| 1V50 | 1V4Z | 19 | 8 | PHOSPHOTHREONINE | 4.154 | Helix | Helix | X |

| 2L5J | 2L5I | 21 | 10 | PHOSPHOSERINE | 5.136 | Loop | Loop | X |

| 3NAY | 3NAX | 311 | 241 | PHOSPHOSERINE | 2.786 | Loop | *1 | |

| 1KKM | 1KKL | 100 | 46 | PHOSPHOSERINE | 0.322 | Loop | Loop | |

| 3IAF | 3IAE | 570 | 28 | PHOSPHOSERINE | 0.468 | Helix | Helix | |

| 1H4X | 1H4Y | 117 | 57 | PHOSPHOSERINE | 1.661 | Loop | Helix | |

| 3FDZ | 3EZN | 257 | 9 | N1-PHOSPHONOHISTIDINE | 0.500 | Loop | Loop | |

| 1VSQ | 2JZN | 133 | 10 | N1-PHOSPHONOHISTIDINE | 0.000 | Loop | Loop | |

| 2NU6 | 2NU7 | 288 | 246 | N1-PHOSPHONOHISTIDINE | 0.130 | Loop | Loop | |

| 3LMH | 3LLA | 307 | 766 | ASPARTYL PHOSPHATE | 0.462 | Loop | Loop | |

| 1DC8 | 1DC7 | 124 | 54 | ASPARTYL PHOSPHATE | 3.236 | Loop | Loop | X |

| 2FPW | 2FPS | 176 | 10 | ASPARTYL PHOSPHATE | 0.185 | Loop | Loop | |

| 2R5C | 2R5E | 429 | 255 | C6P* 2 | 1.045 | Helix | Helix | |

| 1S06 | 1S07 | 429 | 274 | C6P* 2 | 0.422 | Helix | Helix | |

| 1YIZ | 1YIY | 429 | 255 | C6P* 2 | 0.303 | Helix | Helix | |

| 2BHT | 2BHS | 303 | 41 | C6P* 2 | 1.338 | Helix | Helix | |

| 3CQ6 | 3CQ5 | 369 | 228 | C6P* 2 | 0.353 | Loop | Loop | |

| 3SOW | 3SOU | 9 | 4 | N-TRIMETHYLLYSINE | 1.062 | Loop | Loop | |

| 2H9P | 2H9M | 11 | 4 | N-TRIMETHYLLYSINE | 0.041 | Loop | Loop | |

| 3F9X | 3F9W | 10 | 20 | N-DIMETHYL-LYSINE | 0.282 | Strand | Strand | |

| 2H9N | 2H9M | 11 | 4 | N-METHYL-LYSINE | 0.388 | Loop | Loop | |

| 3S7D | 3S7F | 13 | 370 | N-METHYL-LYSINE | 0.219 | Strand | Strand | |

| 3F9Y | 3F9W | 10 | 20 | N-METHYL-LYSINE | 0.381 | Strand | Strand | |

| 2KNN | 2KNM | 30 | 6 | 5-O-METHYL-GLUTAMIC ACID | 2.400 | Strand | Strand | X |

| 1J4T | 1J4S | 149 | 1 | N-ACETYLALANINE | 0.423 | Loop | Loop | |

| 2KWJ | 2KWK | 20 | 14 | N(6)-ACETYLLYSINE | 6.284 | Loop | Loop | |

| 1MJA | 1FY7 | 278 | 304 | S-ACETYL-CYSTEINE | 0.006 | Loop | Loop | |

| 1DM3 | 1DLU | 389 | 89 | S-ACETYL-CYSTEINE | 0.134 | Loop | Helix | |

| 2BAQ | 2BAJ | 365 | 162 | S-MERCAPTOCYSTEINE | 1.682 | Loop | Loop | |

| 2AP8 | 2AP7 | 20 | 2 | D-ISOLEUCINE | 2.489 | Loop | Loop | |

| Total | 40 | pairs | AVERAGE | 1.765 | ||||

| STD DEV | 3.723 |

Denotes secondary structure for this portion of the protein was not elucidated experimentally

2-LYSINE(3-HYDROXY-2-METHYL-5-PHOSPHONOOXYMETHYL-PYRIDIN-4-YLMETHANE)

3 Results

3.1 Forcefield Parameters Compatible with ff03 for 32 PTMs

Parameters for the partial charges, force constants, and equilibrium values for bond, angle, and torsion terms were calculated and derived for each of these post-translational modifications as described in Methods. Specifically, we present parameters for Dimethylarginine (symmetric and anti-symmetric), ω-methylarginine, cysteinepersulfide, cysteine sulfenic acid, phosphocysteine (neutral), S-farnesylcysteine, S-geranylgeranylcysteine, S-palmitoylcysteine, 1-carboxyglutamic acid (neutral), pyrrolidonecarboxylic acid, 5-hydroxylysine, ε-N-methyllysine, N-ε-acetyllysine, N6,N6-dimethyllysine, N6,N6,N6-trimethyllysine, dihydroxyphenylalanine, 3,4-hydroxyproline, 3-hydroxyproline, 4-hydroxyproline, phosphoserine (−2 charge), phosphoserine (neutral), phosphothreonine (−2 charge), phosphothreonine (neutral), 7-hydroxytryptophan, phosphotyrosine (−2 charge), phosphotyrosine (neutral), pyrrolysine, ornithine, 5-hydroxytryptophan, N6-propanoyllysine, and N6-butanoyllysine. The new parameters for each PTM organized by their canonical amino acid scaffold are presented in Supporting Information section Forcefield Parameters for Each Post-Translational Modification Grouped by Scaffold Residue, along with images of each with atom names labeled consistently with PDB conventions (see section Images of Each Parameterized Post-Translational Modification Grouped by Scaffold Residue). An AMBER compatible input file with instructions for use is also provided in the Supporting Information.

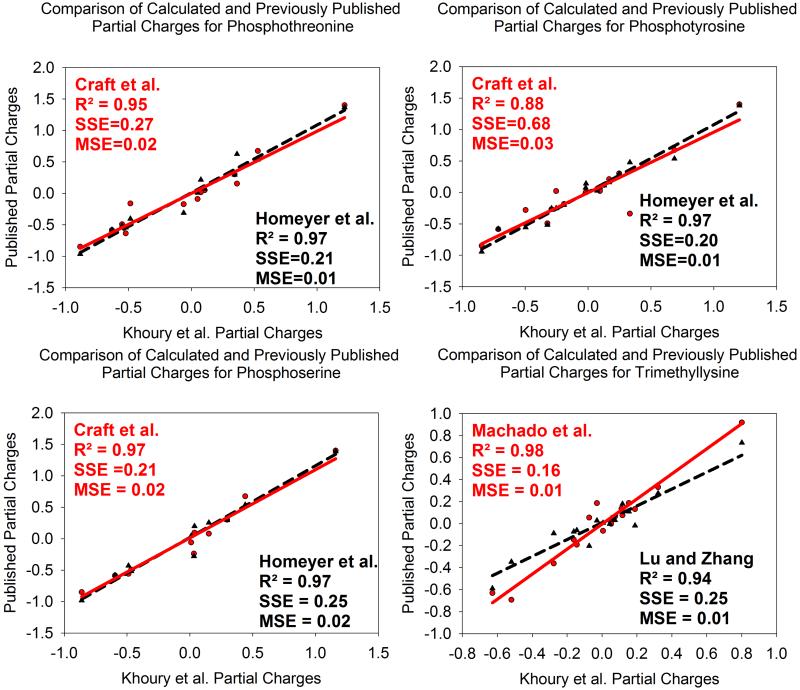

3.2 Comparison of Calculated Partial Charges with Published Charges in Literature

To give guidance in the cases where partial charges for modified amino acids have been previously published, the calculated partial charges from this work are compared for the phosphorylated amino acids,42,43 and for trimethyllysine.46,47 The phosphorylated amino acids compared are those in the deprotonated forms, often present at physiological pH, containing a net −2 total charge. The results are presented in Figure 2. These partial charges were calculated based on the α-helical and β-strand conformers generated in TINKER and optimized in Gaussian.

Figure 2.

Comparison of calculated partial charges in this work to Craft et al.42 and Homeyer et al.43 for deprotonated phosphothreonine (A), phosphotyrosine (B), and phosphoserine (C). Calculated partial charges were next compared with those from Machado et al.47 and Lu and Zhang46 for trimethyllysine (D). The calculated charges were found to be similar and consistent with previous work, despite methodological differences, with small mean squared errors and high squared correlation coefficients.

Comparing the phosphorylated amino acids, it is clear that the calculated partial charges in this work are consistent with those in the literature,42,43 with a mean squared error less than 0.03 in all cases. Comparing the calculated partial charges for trimethyllysine to those available in the literature,46,47 similarly it is observed that the charges are consistent, with a mean squared error less than or equal to 0.01 in both cases. Homeyer et al.43 and Lu and Zhang46 developed parameters for the ff94/ff99 parameter set using fixed charges on backbone atoms as previously described,41,87 whereas charges developed by Craft et al.42 and Machado et al.47 were calculated in Insight II. Although the backbone charges are fixed in the parameterization method in ff94/ff99, there was a high level of correlation between those charges of Homeyer and Lu to the charges calculated using the ff03 method in this work.

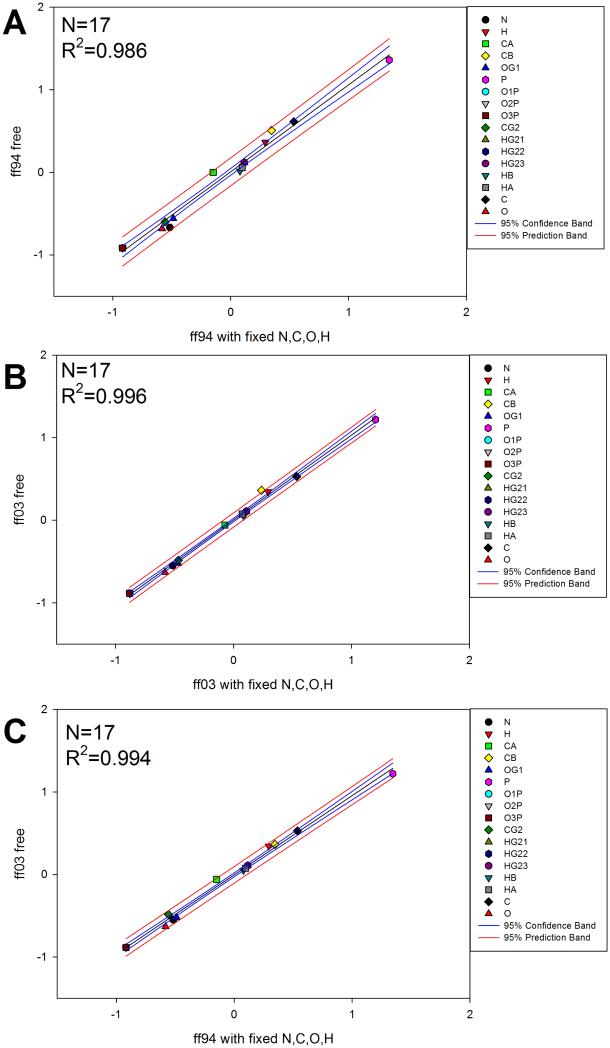

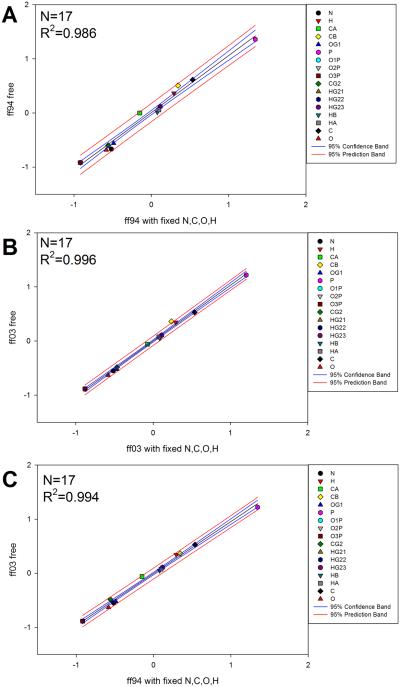

To develop this further, we took the case of phosphothreonine and calculated the partial charges using both the ff94 and ff03 methodologies, both with fixed backbone charges and with unrestrained (free) backbone charges, as shown in Figure 3. We observe that when utilizing the different quantum calculation methodologies with and without restraints, the corresponding calculated partial charges are highly correlated. Although there is a high level of correlation, there is an absolute difference between the fixed values.

Figure 3.

Calculation of partial charges for deprotonated phosphothreonine (−2 charge) using multiple quantum methods and restraint choices. When backbone atom charge restraints are used, they refer to restraints on the N, C, O, and H atoms. (A) Calculation of partial charges using ff94 methodology with fixed backbone charges vs. leaving them unrestrained (free). (B) Calculation of partial charges using ff03 methodology with fixed backbone charges vs. leaving them free. (C) Calculation of partial charges using ff94 methodology with fixed backbone charges vs. ff03 methodology. Red and blue lines represent the 95% confidence and prediction bands, respectively.

We next assessed the absolute differences in the fixed backbone partial charges of the heavy atoms used in ff94 according to groups by charge (positive, negative, neutral, proline). For each of the modified amino acids parameterized, we calculated the % Absolute Deviation between the calculated charges using the ff03 method in this work and the expected fixed charges defined in ff94 for the heavy N, C, and O atoms on the backbone. Additionally, we assessed the deviation with the scaffold residue’s Cα charge, which was not fixed in ff94, for each PTM. This is noteworthy since the same backbone charges have been carried through from ff94 to ff99/ff99SB and ff12SB. In Figure 4, we observe moderate differences between the N, C, and O heavy atoms which have their charges fixed to specific values in ff94. The average absolute deviations for N, C, and O were 28.01 ± 19.83%, 13.01 ± 13.27%, and 5.40 ± 5.42 across the 32 modified amino acids. Conversely, we observed large differences on the Cα atom of several modified residues, with average absolute deviations of 488.51 ± 1011.35%. The large percent deviation in the Cα partial charges can be attributed to the small magnitude partial charges present in the scaffold residues and where upon post-translational modification, changes the local electrostatic environment of that atom. These results suggest that the magnitudes of the partial charges calculated in the condensed-phase using the ff03 method naturally deviate from the values derived for ff94 in the gas phase. Fixing the charges to the consensus charges derived for the natural amino acids yields poor quality of fits due to the additional functional groups and electrons on the PTMs, stemming from their interactions with the ghost atoms outside of the molecule during the electrostatic potential calculations. If one was to derive new parameters in the spirit of ff94 for PTMs, given the moderate absolute deviations of the backbone atom charges from the consensus values, it would be expected based on these results that new consensus values may be warranted accounting for both natural and post-translationally modified amino acids for each of positive, negative, neutral, and proline groups.

Figure 4.

Comparison of backbone partial charges calculated using the ff0359 method in the condensed-phase, with the ff94 fixed backbone partial charges for N, C, and O atoms calculated in the gas phase. The CA charge value is taken to be its value in the scaffold residue (for example, serine for phosphoserine) and is not fixed during the parameterization of the scaffold residues in ff94. The y-axis plots the % absolute deviation from the expected value defined in ff94 depending on whether the residue is negative, neutral, positive, or proline for the N, C, and O atoms, or the scaffold residue CA value.41 The x-axis is ordered by the aforementioned groups.

Encouraged by the consistency between the calculations in this work and those previously published, and noting the differences in the parameterization methods, the background levels of structural dissimilarity in our test set of modified/unmodified protein structures were next evaluated so that the parameters could be compared using molecular dynamics.

3.3 Characterization of Background Structural Similarity Between Modified/Unmodified Structures and Distribution of PTM Density Contained in the PDB

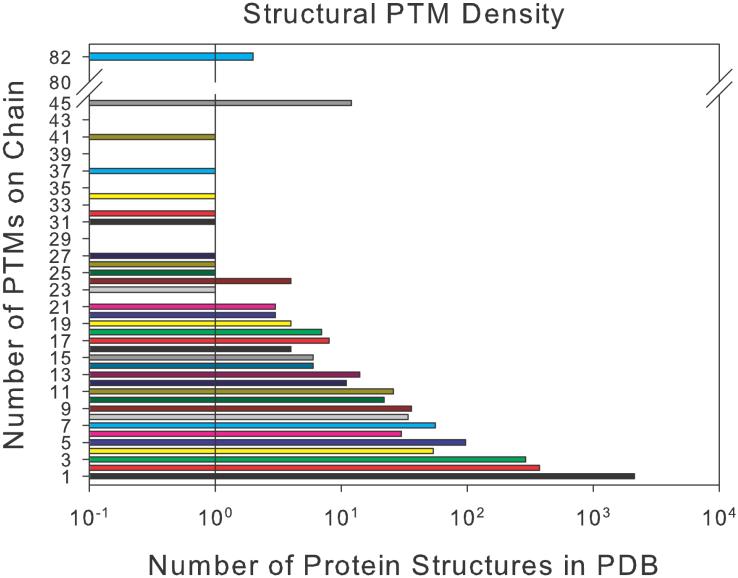

To test the forcefield for modified amino acids in comparison to its unmodified counterpart, we found pairs of modified and unmodified structures in the PDB and characterized their structural similarity using the method described in Supporting Information sections Automated Curation of Pairs of Modified and Unmodified Protein Structures Contained in the PDB and Structural Characterization of Baseline Secondary Structure and Tertiary Structure Features to Establish Background Control Levels. The PTM density of the structures contained in the PDB on a log10 scale is presented in Figure 5. The raw data for the distribution, as well as the full set of PDB IDs organized by number of modifications is provided in the Supporting Information File pdbptmdistribution.zip.

Figure 5.

PTM density of all experimental structures not containing disulfide bridges contained in the PDB.

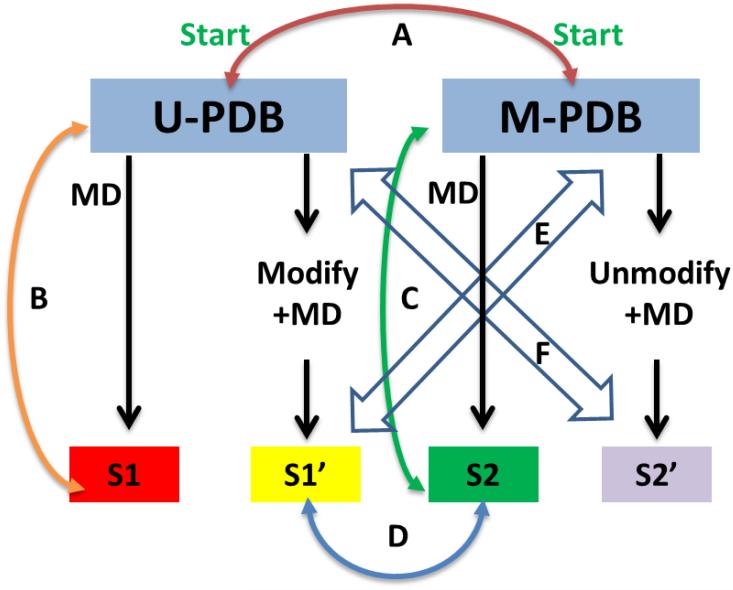

The distribution observed spans four orders of magnitude with most post-translationally modified structures (2136) containing only a single modification and about half as many (1115) containing multiple modifications. Structures containing a single modification were largely distributed among phosphorylation, methylation, and glycosylation among the top 10 most frequently contained in the PDB. Knowing the distribution of PTMs on the structures in the PDB allowed the search for all pairs of singly and multiply modified structures. Using this information, we present a global quantitative analysis on the secondary and tertiary structure dissimilarity between modified and unmodified protein structures in Table 1 to establish the background levels for use in parameter testing. This serves as Comparison A denoted in Figure 8. We denote whether the modification is the cause of structural change based on visualization of the alignment of the modified and unmodified pairs, as well as from referring to the papers where the structures were solved.

Figure 8.

Comparisons performed in this work. (A) Intrinsic structural dissimilarity between the modified (M-PDB) and unmodified (U-PDB) structures contained in the PDB. These were assessed by aligning the modified and unmodified structures contained in the PDB with each other. (B) Structural similarity between the unmodified structure (U-PDB) and states of unmodified structure simulation (S1). (C) Structural similarity between modified structure (M-PDB) and states of the modified structure simulation (S2). (D) The structural similarity between states of the modified structure simulation (S2) and the states of the unmodified crystal structure, modified and simulated (S1’). (E) Comparison of the states of the simulation of the unmodified PDB structure (U-PDB) when modified (S1’) to the modified PDB structure (M-PDB). (F) Comparison of the states of the simulation of the modified PDB structure (M-PDB) when unmodified (S2’) to the unmodified PDB structure (U-PDB).

Several features are evident in this curated dataset. First, there are not many pairs of modified and unmodified structures that have been experimentally characterized to date. Second, taking a consensus of three different secondary structure methods and observing the changes in local secondary structure, we found that 95% did not change. It was also observed that over the 40 modified and unmodified pairs, the average Cα RMSD is 1.765Å. In similar accord, 20% of the tertiary structures had a Cα RMSD of greater than 2.4Å, indicating a moderate structural change. The modification was the cause of these structural changes in 5 of the 40 pairs according to a visualization of their alignments, coupled with analysis of the literature describing the solution of their structures. Finally, it is important to note that the set of modifications included in this set is strongly biased by phosphorylations, which is unsurprising given that they dominate the modificome experimentally observed and annotated to date.32

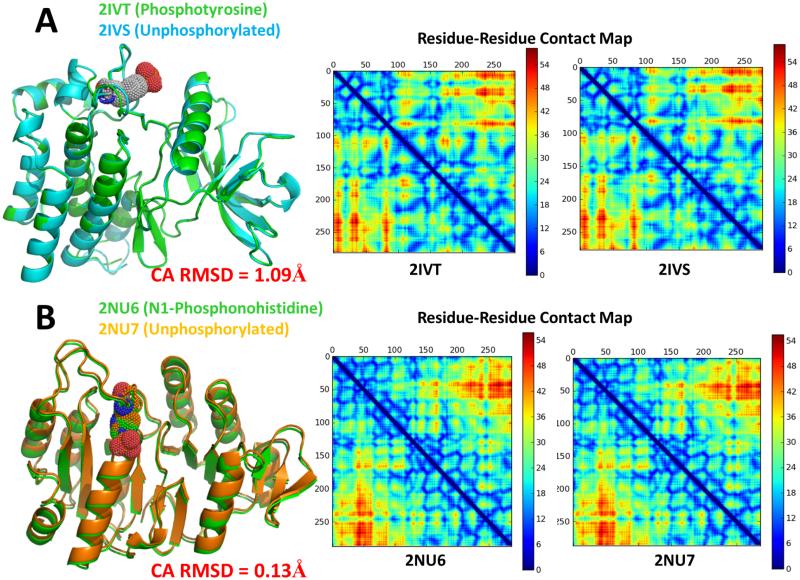

We highlight several pairs of singly modified and unmodified pairs of structures along with their corresponding residue-residue contact maps to clearly show inter-residue contacts. In Figure 6, two pairs of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated structures are presented. 2IVT is the crystal structure of the phosphorylated RET tyrosine kinase domain from H. sapiens, whereas 2IVS is the corresponding unphosphorylated form. Aligning the two structures shows the clear lack of structural deviation as a result of the phosphorylation. The contact map confirms them to have identical backbones. It would be expected that their secondary structures behave similarly. Additionally, both 2NU6 and 2NU7, structures of E. coli Succinyl-CoA Synthethase in both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms are nearly structurally identical. It is noteworthy that the cysteine in position 123 is mutated to an alanine in 2NU6, whereas the sequence contains a serine in that position in 2NU7.

Figure 6.

(A) Alignment of 2IVT, which is phosphorylated, to 2IVS, its corresponding unphosphorylated form. The total Cα RMSD is 1.09Å between the two structures. (B) Alignment of 2NU6, which contains a phosphorylated histidine residue, to 2NU7, its corresponding unphosphorylated form. The total Cα RMSD is 0.13Å between the two structures. In both examples, the contact maps are presented. The contact map denotes whether and how far away contacts exist between residues i and j along the length of the sequence. Contacts between residues which are closer than 5 residues to each other in sequence are ignored (indicated by the blue line across the diagonal). The colors on the contact map denote the distance between the residue-residue contacts in Å.

This lack of structural change is not just observed on phosphorylated structures in the PDB. In an alignment of a 10-amino acid fragment of Histone H4 from H. sapiens in both its dimethylated (3F9X) and unmethylated forms (3F9W), we find the structures have identical secondary structures according to DSSP,88 and a Cα RMSD of 0.28 Å.

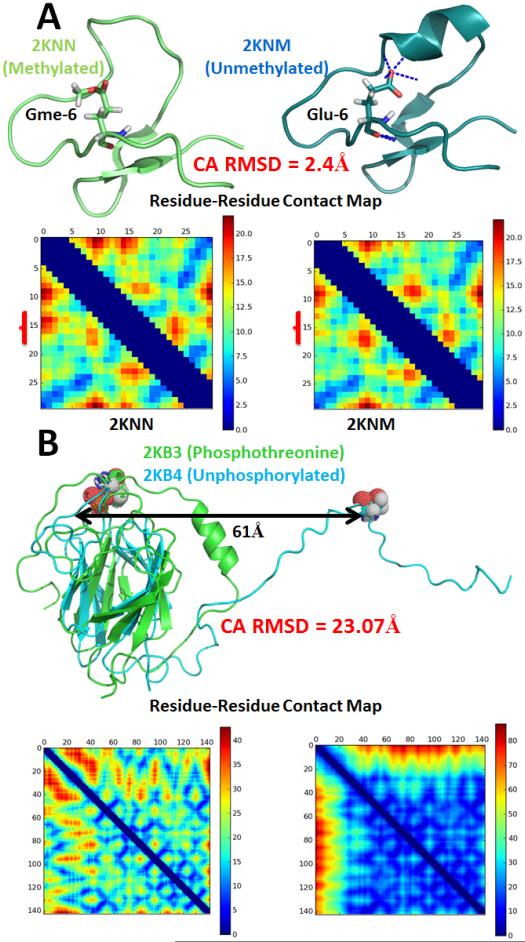

Nevertheless, secondary and tertiary structures can change as a result of PTMs. We present two examples from the pairs of modified/unmodified structures curated from the PDB in Figure 7. Unlike what was observed in Figure 6 and with the histone tail fragment, these are two cases where methylation and phosphorylation cause drastic changes in the tertiary structure. 2KNN and 2KNM are the methylated and unmethylated forms of cycloviolacin O2 from Viola odorata. Glu-6 is conserved in the cyclotide family, and methylation of this conserved residue structurally leads to a non-local loss of helicity in residues 14-18, a 2.4 Å change in RMSD, and biologically leads to the loss of its activity.89 2KB3 and 2KB4 are the phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of OdhI, a key regulator of the TCA cycle in Corynebacterium glutamicum.90 Phosphorylation of threonine in position 15 is the cause of a large 23Å shift in the Cα RMSD between the pair in one conformation of this structure resolved by NMR. In addition to the structure alignments, contact maps confirm the overall structural dissimilarity. Locally, with the exception of the phosphorylated region, the core is preserved though, as 102 of the 142 residues align with a Cα RMSD of 1.86 Å.

Figure 7.

(A) Methylation of Glu-6 in cycloviolacin O2 (2KNN) causes a modest non-local secondary structure change by blocking the previously formed hydrogen bond interactions between Glu-6 and residues 14-18 on 2KNM. The brackets outside the contact map highlight the region of residues 14-18 where there is a change. 2KNM contains 1 α-helix and β-strands whereas the modified form 2KNN contains only 3 β-strands. (B) In contrast, the active form of OdhI is unphosphorylated (2KB4). Phosphorylation (2KB3) causes a large structural change of 23.07Å and leads to this protein’s inactivation. The colors on the contact map denote the distance between the residue-residue contacts in Å. 2KB3 contains one α-helix and 11 β-strands whereas 2KB4 contains 11 β-strands. Secondary structures were evaluated with DSSP.88

The aforementioned observations lead us to the question, Does the tertiary structure change when modified multiple times in comparison to single modifications, and if so, how much? To address this question, we adapted our screen-scraping procedure to curate pairs of multiply modified and unmodified structures from the PDB. We present the answer to this question in Table 2 based on the complete dataset currently available as curated from the PDB. The screen-scraping procedure, which looked through each related structure from the set of structures identified to contain more than one modification, identified 10 pairs of multiply modified/unmodified structures.

Table 2.

Comparison of All Pairs of Modified and Unmodified PDB Structures Curated fro the PDB for Multiple Modified Amino Acids

| Modified PDB |

Unmodified PDB | Length of Protein/ Domain |

Number of Modifications |

Modification Type | Cα RMSD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2ZZE | 2ZZF | 752 | 41 | N-DIMETHYL-LYSINE × 40 | 1.039 |

| CYSTEINESULFONIC ACID × 1 | |||||

| 2WL4 | 2VTZ | 392 | 2 | S-HYDROXYCYSTEINE | 0.233 |

| CYSTEINE-S-DIOXIDE | |||||

| 2WL4 | 2WKV | 392 | 2 | S-HYDROXYCYSTEINE | 0.283 |

| CYSTEINE-S-DIOXIDE | |||||

| 1U9I | 1TF7 | 519 | 2 | PHOSPHOSERINE | 0.307 |

| PHOSPHOTHREONINE | |||||

| 1UGR | 1UGS | 203 | 2 | 3-SULFINOALANINE | 0.148 |

| S-HYDROXYCYSTEINE | |||||

| 2WTV | 2WTW | 285 | 3 | PHOSPHOTHREONINE × 2 | 3.093 |

| S,S-(2-HYDROXYETHYL)THIOCYSTEINE | |||||

| 2AQ5 | 2B4E | 402 | 5 | S-HYDROXYCYSTEINE × 4 | 0.365 |

| S,S-(2-HYDROXYETHYL)THIOCYSTEINE | |||||

| 2DD5 | 2DD4 | 243 | 2 | 3-SULFINOALANINE | 0.135 |

| S-HYDROXYCYSTEINE | |||||

| 2CI1 | 2C6Z | 275 | 3 | S-NITROSO-CYSTEINE | 0.160 |

| L-HOMOCYSTEINE-S-N-S-L-CYSTEINE | |||||

| N-THIOSULFOXIMIDE | |||||

| 2ERK | 1ERK | 365 | 2 | PHOSPHOTHREONINE | 2.491 |

| O-PHOSPHOTYROSINE | |||||

| Total | 10 | pairs | AVERAGE | 0.825 | |

| STD DEV | 1.023 |

Several observations can be made. First, there are very few pairs of multiply modified and unmodified structures that have been solved and deposited into the PDB. Second, among the pairs that exist, the average change in Cα RMSD on a per-modification basis is less than 0.3Å. On a total structural basis, 80% of the structures did not change substantially in this set, with an average Cα RMSD of 0.825.

This dataset contains a representative set of all modified and unmodified pairs of structures for single and multiple modifications in the PDB so that direct comparisons between the modified and unmodified structures can be made. The dataset does not contain structures where the single modification is a disulfide bridge, nor in the case of multiple modifications does it contain the structures with one or more disulfide bridges to limit the analysis as much as possible to the effect of the modification. Other pairs of modified and unmodified structures containing disulfide bridges do exist in the PDB. An analysis of glycosylation, phosphorylation, acetylation, and methylation was recently performed based on PDB structures91 and is largely in agreement with our global analysis above. Although the dataset is complete relative to the PDB, it is far from complete in terms of containing a statistically significant number of observations of modified proteins to generalize about the modificome as a whole. This step was performed to assess the intrinsic structural dissimilarity between modified and unmodified pairs of proteins to gain information on how much expected dissimilarity could be expected when they are simulated and compared with each other. Now that the background structural dissimilarity has been assessed, we next begin to test the forcefield in the context of these results.

3.4 Testing FF_PTM with ff03

We performed many sets of structural and simulation comparisons to ensure the reliability of the new charges calculated for the PTMs contained in FF_PTM on a macroscopic scale. A summary of structural and simulation comparison protocols is shown in Figure 8 for guidance. U-PDB refers to the unmodified structure contained in the PDB. M-PDB refers to the modified structure contained in the PDB. These structures either come from X-ray crystallography or from solution NMR. Comparison A between U-PDB and M-PDB, assessing the intrinsic structural dissimilarity between the modified and unmodified structures was performed elsewhere in this work (see Table 1). We performed unrestrained molecular dynamics on 17 pairs of modified and unmodified systems and performed an analysis of secondary structure, tertiary structure, and energetic stability for structures that contain single modifications. Comparisons of the simulation states with the native PDB structures were performed (Comparisons B and C). Comparisons D and E were performed using a simulation of the modified structure 3S7D compared to a corresponding simulation of its unmodified structure (3S7F), and a simulation of its unmodified structure when modified (S1’ to M-PDB), yielding the same final state after 5 ns and comparable side-chain distributions. The states of all three simulations were compared with their corresponding U-PDB. Additional examples of Comparisons D and E are presented in Supporting Information section Plots of Energetics, Secondary Structure, and Tertiary Structure Space Sampled for Pairs of Modified/Unmodified Proteins, and these served as additional datapoints in addition to the aggregate results of the pairs. Simulations of the phosphorylated form of OdhI when dephosphorylated was compared to its phosphorylated PDB structure (Comparison C) and to the dephosphorylated structure (Comparison F). Thus, every combination of meaningful structural comparisons of states is assessed.

3.4.1 Molecular Dynamics Simulations Using Existing Pairs of Modified and Unmodified PDB Structures

Unrestrained all-atom molecular dynamics simulations in the presence of implicit water solvent were performed for 17 of the 40 pairs of singly modified/unmodified structures found in the curation effort. Most structures chosen for these simulations were among those where the modified/unmodified structures were similar to begin with so that any significant differences attributed to observable properties would be caused by the forcefield parameters. The raw simulation results are presented in the Supporting Information section Energetic and structural statistics collected over the course of 5ns all-atom MD simulations for 17 pairs of modified/unmodified structures.

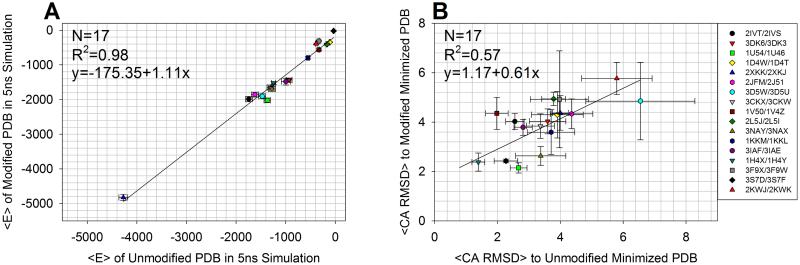

The following simulations address Comparisons B and C as shown in Figure 8. In Figure 9A, we address the question of whether the simulation energetics were stable. Comparing the modified and unmodified simulation trajectories in terms of their average total energy, we found that the correlation between the trajectories had an R2 of 0.98, indicating that there is a high correlation between the energetics of the modified and unmodified structures. When comparing the modified and unmodified proteins’ energetics, since the protein partners contain different numbers of atoms due to one having a modified side-chain, it is not expected that the average total energy would be perfectly identical with R2 = 1 and a slope of 1. As a result of the pairwise additive AMBER forcefield, the energies will be necessarily different. Figure 9A includes error bars in both directions denoting one standard deviation of the energy for both the modified and unmodified forms. Based on the small magnitude of the standard deviation relative to the total energy in each case, we can conclude that the simulations using the new parameters for the PTMs were stable. Additionally, it would be expected that the standard deviation of the energy in the simulation of the modified and unmodified structures should be nearly identical, as the modified and unmodified structures should have similar heat capacities, the thermodynamic quantity that can be derived from the fluctuations of the total energy.

Figure 9.

(A) Correlation between average total energies for 17 pairs of modified and unmodified proteins. Error bars on the energy represent one standard deviation from the average. The correlation between the energies of the modified to the unmodified structures is high, indicating that the simulations for both forms were both stable energetically. (B) Correlation between average Cα RMSD between conformers sampled along the MD trajectory and their corresponding energy minimized structures for 17 pairs of modified and unmodified proteins. Error bars represent one standard deviation from the average.

We assessed the structural stability of the pairs of modified/unmodified proteins undergoing simulation. For each conformer in the trajectory, the Cα RMSD was calculated between the conformer and the minimized PDB structure. At the end of the simulation, the results were averaged. Figure 9B summarizes the results, and the full time evolution of the modified/unmodified pairs are contained in the Supporting Information section Plots of Energetics, Secondary Structure, and Tertiary Structure Space Sampled for Pairs of Modified/Unmodified Proteins. The correlation between the average RMSDs of the modified to the unmodified structures throughout the simulation is moderate (R2 = 0.57), and not as high as that for the energy. This may be expected as structurally the modifications may affect the microenvironment of the protein, leading to a more diverse set of conformations sampled on average, with many of these conformations having similar energies. The sampled space of the modified/unmodified structures is similar in terms of standard deviations denoted by the error bars. Also, it is expected that there may be some intrinsic dissimilarity due to the nature of Langevin dynamics. The structural deviations in unrestrained simulations of the modified and unmodified structures were in general comparable on the aggregate, with the exception of 2L5J/2L5I, which is described in the Supporting Information section Supplementary Discussion on 2L5J/2L5I Deviation in Simulation.

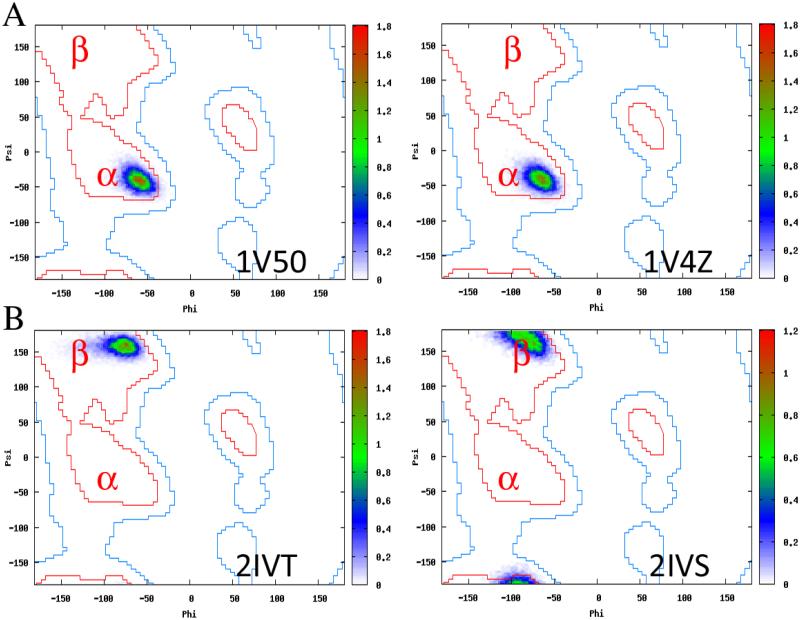

We next highlight several specific results along the MD calculations for regions where the modification occurred on an α-helix and a β-strand. In Figure 10A, we show the Ramachandran angle distributions for both the modified and unmodified structures of the helical peptide Calgizzarin. The modification occurred in a position that began as a helix, and Figure 10A shows that the helical conformation was maintained throughout the production simulation for 1V50/1V4Z. For 2IVT/2IVS, a pair of modified/unmodified structures where the phosphorylated residue and unphosphorylated residue begins in the β regime (Figure 10B, we observed that the modified/unmodified residue remained within the β region of the Ramachandran plot. These were two examples from the set of simulations performed, and we provide Ramachandran plots for each position modified for each pair of modified/unmodified structures in the Supporting Information section Plots of Energetics, Secondary Structure, and Tertiary Structure Space Sampled for All Pairs of Modified/Unmodified Proteins. In almost every case in which the single residue modified had both ϕ and ψ dihedral angles, the initial secondary structures were found to be preserved. Therefore, we conclude that the parameters derived generally allow the initial secondary structures to be preserved.

Figure 10.

(A) Ramachandran plot of the dihedral angles sampled by the phosphorylated (1V50) and unphosphorylated (1V4Z) forms of Calgizzarin during the simulation. The position that is phosphorylated in 1V50 started (at t=0 of the production run) in the helical region and the corresponding position on 1V4Z began in the helical region. During the simulation, the helicity was preserved in the region modified and the overall helical structure was preserved. (B) Ramachandran plot of the dihedral angles sampled by the phosphorylated (2IVT) and unphosphorylated (2IVS) RET tyrosine kinase domain from H. sapiens. The position phosphorylated on 2IVT and the corresponding position on 2IVS began in the β regime as assessed by the consensus of secondary structures shown previously. Both forms remained in the β regime throughout the simulation. These examples serve to illustrate what was generally observed across all pairs of modified/unmodified structures assessed.

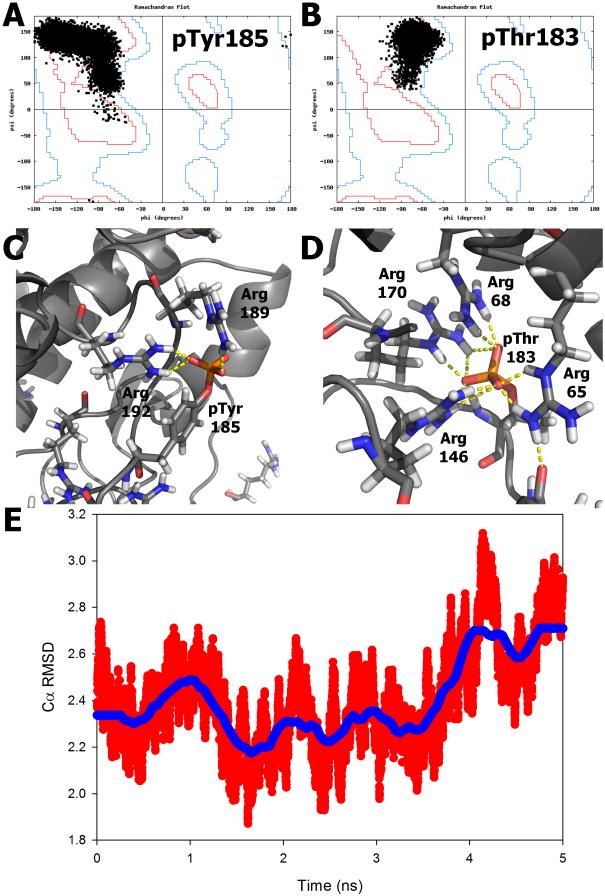

For completeness, we next examine the case of simulations with multiple modifications where the modifications occur on loops. 2ERK is the phosphorylated structure of MAP kinase ERK2. It contains both a phosphothreonine and a phosphotyrosine residue, both occurring on loop regions. 1ERK is its corresponding unmodified structure. It is desirable to ensure that the secondary structure in both positions remained preserved throughout the simulation. In Figures 11A and B, we present a Ramachandran plot of the phosphorylated positions over the course of the simulation. The dihedral angles of these positions sampled space consistent with what would be expected in a residue occurring on a loop. Figures 11C and D depict the network of salt-bridge and hydrogen bond interactions formed between the post-translationally modified residues in ERK2 during the last snapshot of the 5 ns simulation. The PDB structure and final structure when aligned had high structural similarity, even at an atomic level at the end of 5 ns simulation (3.64 Å all-atom RMSD). Figure 11E depicts the relative preservation of the backbone to the crystal structure of ERK2 during the simulation. Overall, from all of the simulation results on a macroscopic scale, we conclude that the secondary structures remain conserved and the tertiary structures deviate at comparable levels from the native to their corresponding unmodified counterpart using the charges and parameters derived for FF_PTM.

Figure 11.

Ramachandran plot of the dihedral angles sampled by the phosphorylated tyrosine in position 185 (A) and the phosphorylated threonine in position 183 (B) in the structure of MAP kinase ERK2. The secondary structure of both positions remain preserved over the course of the simulation. Network of salt-bridge and hydrogen bond interactions formed between phosphorylated tyrosine 185 (C) and threonine 183 (D). (E) Backbone RMSD to the minimized crystal structure of ERK2 over the course of the production simulation. 10,000 time points were taken over 5ns shown in red, with the running average shown in blue. The atomic coordinates of the backbone of the overall structure remained stable throughout the simulation in addition to the coordinates of the phosphorylated side-chains.

3.4.2 Simulating the Conformational Change Associated with Dephosphorylation of OdhI

This section is presented to perform Comparison F as shown in Figure 8. The N-terminus of OdhI, a key regulator of the TCA cycle in Corynebacterium glutamicum, binds to its own FHA domain when phosphorylated at Thr15, leading to its inactivation, and a stable structure (PDB: 2KB3).90 When the protein is dephosphorylated (PDB: 2KB4), a large conformational change is observed due to the absence of a key stabilizing salt-bridge between pThr15 and Arg87. The unphosphorylated form of OdhI can bind to OdhA and acts as an inhibitor;92 therefore its phosphorylation autoinhibits its inhibitory activity.90 OdhI’s phosphorylation/dephosphorylation and large conformational changes associated present an interesting structural regulatory mechanism controlling the TCA cycle. In contrast with the previous simulations, where the modified and unmodified structures in the PDB were in close resemblance of each other, here the modified and unmodified structures are largely dissimilar at the N-terminus. Therefore, we were interested in assessing whether the forcefield with the new parameters would be able to capture the destabilization of OdhI due to its dephosphorylation relative to its phosphorylated state.

Independent 15 ns simulations were carried out similar to the procedure described previously of 2KB3 and 2KB3 with pThr15 substituted by a Thr (dephosphorylated). Since here we are trying to observe something biologically relevant, as opposed to strictly testing the forcefield, harmonic constraints were applied during the heating and equilibration stages and were removed during production. The simulations began using Model1 of the NMR structure. The states of the phosphorylated and dephosphorylated forms were collected. In Figure 12A, we present an alignment of the phosphorylated (red) and dephosphorylated (blue) structures at the end of the 15 ns simulation, compared with the solution structure of OdhI (grey). Figure 12B and C show the conservation of the key stabilizing salt-bridge between pThr15 and Arg87 and its much larger distance away from the expected value when it is dephosphorylated at the end of the simulation. The distance between pThr15 and Arg87 shows the existence and persistence of a salt-bridge, whereas shortly after the dephosphorylation simulation begins, the distance between Thr15 and Arg87 increases (Figure 12D). The backbone RMSD over residues 1 to 39 over the course of the simulation is substantially higher in the dephosphorylated form at 8.28±1.53 Å (Figure 12E) due to the missing salt-bridge, similar to what is observed in the NMR structure 2KB4. The phosphorylated form has an average backbone RMSD is 6.68±0.84 Å. Additionally, Figure 12F indicates that the core of both the phosphorylated and dephosphorylated structures remains stable (average backbone RMSD of 2.97±0.39 Å and 3.27±0.45 Å, respectively), as observed in the original solution of both structures.90 Figures 12G and F show the movement of residues 1-39 over time in the phosphorylated (G) and dephosphorylated (F) structures, with the core of the NMR structure (black). The colors in G and F represent equivalent time snapshots in each simulation. Key interactions that were observed throughout the 15 ns simulation in the modified structure were in agreement with observations made in the phosphorylated NMR structure 2KB3 (Figure 12I).90 Namely, pThr15 can form a network of stabilizing interactions with Glu13, Arg72, Ser86, Arg87, Ser106, Leu107, Asn108, and Gly109. These interactions, directed in orientation by pThr15, form other hydrogen bonds and salt-bridges to keep the first 39 residues of the OdhI relatively ordered compared to the dephosphorylated form. This simulation was carried out three times independently, observing similar behavior each time; preservation of the key pThr15:Arg87 salt-bridge, and a large conformational change in the absence of the salt-bridge. We observed similar results when carrying out the simulation without any restraints in the heating and equilibration stages.

Figure 12.

(A) Alignment of 2KB3 NMR structure (grey), 2KB3 after 15 ns simulation (red), 2KB3 dephosphorylated in position 15 to threonine (blue). The salt bridge bridge that stabilizes the 2KB3 structure and biologically inactivates it is shown between pThr15 and Arg87. (B) Close view of salt-bridge preservation between pThr15 and Arg87 at the end of the 15 ns simulation. (C) Close-up view of large distance between the dephosphorylated Thr15 and Arg87. (D) Distance between Thr15:OG1 to Arg87:NH2 (blue) and pThr15:P to Arg87:NH2 (red) over time. The salt-bridge in the phosphorylated structure is preserved throughout the simulation (red), whereas shortly after the simulation begins, the Thr15 moves away from Arg87. (E) Backbone Cα RMSD for residues 1-39,90 the region effected most by the phosphorylation over the 15 ns simulation. The phosphorylated structure is more ordered due to the stabilizing salt-bridge, whereas dephosphorylated 2KB3 unfolds in that region without the stapling saltbridge. (F) Backbone Cα RMSD for residues 40-143. This core region of both phosphorylated and dephosphorylated forms was found to be stable in both NMR structures, and is found to be stable over the simulation. (G) Superposition of the coordinates of residues 1-39 in the phosphorylated structure compared to in (H) dephosphorylated structure with the core of the 2KB3 NMR structure (black). The color bar represents the fraction of the 15 ns simulation completed. The dephosphorylated structure becomes disordered deeper into the sequence as it unfolds. (I) Network of key salt-bridge and hydrogen bond interactions with pThr15 largely agrees with observations made by Barthe et al.90 All plots are from the production phase of the simulation.

The molecular dynamics results from this case study in implicit solvent are in agreement with the proposed mechanism and experimental study by Barthe et al.90 We have observed the dynamical effect of the stapling salt-bridge between pThr15:Arg87 in the phosphorylated structure and a large conformational change in the dephosphorylated structure, supporting the necessity of Thr15 and not Thr14’s phosphorylation being the key stabilizing salt-bridge for the autoinhibition of this protein. Whereas in this section we began with a modified structure and examined the effect of removing the modification, we next do the reverse, starting with an unmodified structure and modifying it.

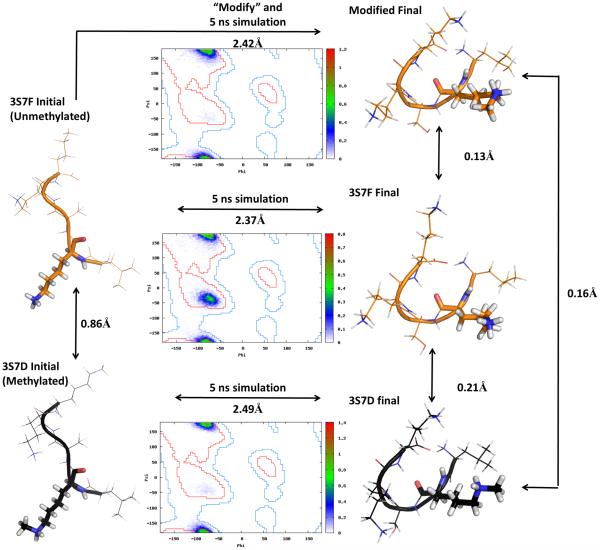

3.4.3 Comparisons of S1’ to S2 and M-PDB

With this new forcefield parameterization, we were interested in determining if one started with an unmodified structure, modified it, and performed a simulation, how far away from the native structure would it be? Would it drift far away, or, would it stay in a stable state nearby? Furthermore, if taking an unmodified structure contained in the PDB, modifying it, and performing a simulation, how similar would the states sampled in the simulation be to that observed from taking the modified structure and directly simulating it. These questions are addressed by Comparisons D and E as shown in Figure 8. For this assessment, it was decided to use a short amino acid sequence with a small number of degrees of freedom so the effect of the modified residue can be more directly assessed. The coordinates of the 5 residue methylated PDB structure 3S7D and its unmethylated counterpart 3S7F were simulated via the procedure described previously. 3S7D is the monomethylated non-histone substrate of the lysine methyltransferase SMYD2, called p53.93 Both peptides begin in a bound conformation. 3S7F, with a lysine in position 2, was next substituted by methyllysine with a mutate function written in Python. The function strips off the side chain atoms in a particular position, replaces the residue name field in the PDB file to the new amino acid, and passes the structure to tleap to generate an initial conformation which can be minimized using the new forcefield (or standard AMBER) parameter sets.

In Figure 13, a schematic diagram shows the steps taken. The modified structure and unmodified structures were initially 0.86 Å dissimilar after local minimization. After simulation from each of the starting coordinates, both 3S7D, 3S7F unmodified, and 3S7F modified were driven to the same stable state evidenced by a less than 0.21 Å Cα RMSD between any two combinations of structures taken at the last snapshot of the 5 ns simulation. Interestingly, the unmodified structure PDB structure 3S7F, when modified, behaved nearly identically to the behavior of the modified PDB structure 3S7D in the independent simulation as evidenced by the Ramachandran plot of the corresponding positions of methyllysine. The structures, which all began in the bound conformation, all found a common new local minima when unbound. This result is interesting given the interactions and conformational changes involved in modifying histone tails, and the resemblance of p53 to a histone tail fragment. Although this simple system contained only 5 residues, this meant the modified lysine residue was responsible for a larger fraction of the trajectory in comparison to several of the larger structures simulated that had hundreds of residues. This protocol of Comparisons D and E has been applied to several additional pairs of substantially larger unmodified/modified proteins resulting in similar findings. These results are presented in the Supporting Information section Plots of Energetics, Secondary Structure, and Tertiary Structure Space Sampled for All Pairs of Modified/Unmodified Proteins.

Figure 13.

Schematic diagram showing procedure of simulation of p53 peptide fragment. The crystal structure of the monomethylated p53 fragment (PDB 3S7D) was simulated following the procedure described in methods. The unmethylated p53 fragment was methylated and simulated. The initial structures and final structures are compared before and after the simulation. The trajectory of each simulation with respect to the minimized monomethylated p53 structure is shown. The Ramachandran plot of the conformations sampled in the methylated position is shown in the inset, with similar backbone conformations sampled. The final states of the independent 5ns simulations that started from the crystal structure of the monomethylated p53 and the unmethylated p53 modified and simulated were nearly identical, with Cα RMSDs of 0.16 Å.

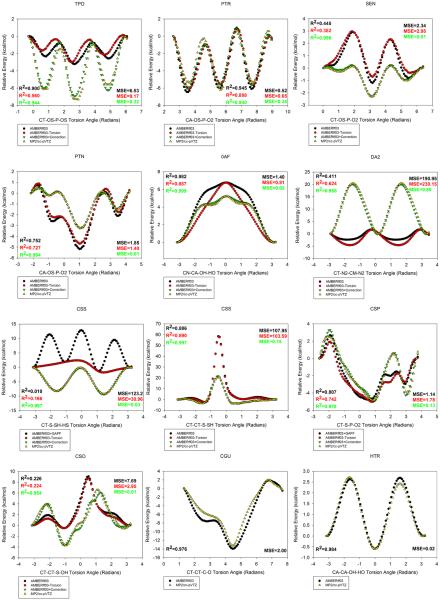

3.5 Improvement in Post-Translational Modification Side-Chain Torsion Terms

Comparisons to geometries calculated ab initio using quantum mechanics-based methods are an important part of forcefield development.59 We did not observe on a macroscopic scale any issues during our simulations (for example, salt-bridges not forming, structural decay more than the unmodified structure in similar length, similar condition simulations, or other simulation artifacts). Next, we wanted to assess on a microscopic scale the ab initio rotational profiles of a series of torsion angles contained in the PTMs that potentially have strong 1-4 interactions and that may benefit from specific torsion corrections.

Thus, for a series of torsion angles contained in the PTMs we began with the α-helical conformation optimized in Gaussian0973 using HF/6-31G** with the IEFPCM implicit solvent model79,80 and a dielectric constant of 4.0 to mimic a diethylether environment. The torsions assessed are: (1) CT-OS-P-OS from negatively charged phosphothreonine (TPO), (2) CT-CT-C-O from 1-carboxyglutamic acid (CGU), (3) CT-CT-S-OH from cysteine sulfenic acid (CSO), (4) CT-OS-P-O2 from neutral phosphoserine (SEN), (5) CT-N2-CM-N2 from antisymmetric dimethylarginine (DA2), (6) CT-CT-S-SH from cysteine persulfide (CSS), (7) CT-S-SH-HS from cysteine persulfide (CSS), (8) CT-S-P-O2 from neutral phosphocysteine (CSP), (9) CN-CA-OH-HO from 7-hydroxytryptophan (0AF), (10) CA-OS-P-O2 from phosphotyrosine (PTR), (11) CA-OS-P-O2 from neutral phosphotyrosine (PTN), and (12) CA-CA-OH-HO from 5-hydroxytryptophan (HTR). The torsions are visually depicted in Supporting Information section Images of Torsion Angles Assessed Using Ab Initio Rotational Profiles. Next, with a torsion step size of 5°, we evaluated the energy at each state through Gaussian at the MP2/cc-pVTZ level of theory and with the IEFPCM implicit solvent model79,80 with a dielectric constant of 4.0. This served to produce an ab initio rotational profile about the torsion, although the torsion potential in AMBER is largely thought to be a correction to enable the quantum and molecular mechanics energies to match.94 These calculations were very computationally expensive for each of the 5° torsion increments per molecule to be assessed.

We evaluated the energies of the conformers with AMBER in the “gas-phase,” with the charge parameters developed in this work with ff03 or ff03 complemented by GAFF parameters used previously when there were missing torsion parameters. This was done in the spirit of the the paramfit procedure, which attempts to make the quantum and AMBER energies be the same over many conformations of a structure.95 We did this in order to assess whether this was the case for the parameters used to carry out the simulations, and if not, to make appropriate corrections. The results are shown in Figure 14. The AMBER energies, based on the parameters used in the MD simulations are shown as black dots. The Gaussian-calculated energies at the MP2/cc-pVTZ level of theory in an ether-like environment for each of the points are shown in yellow. The correlation and mean-squared errors are depicted in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Ab initio rotational profile (yellow) of 12 torsions on 11 PTMs in comparison to AMBER potential based on the parameters used in our MD simulations (black), and corrections derived using Fast Fourier Transform. AMBERff03-torsion denotes the molecular mechanics energy without the contribution from the torsion to be fit. AMBERff03+Correction denotes the fitted torsion parameters added to the ff03 potential (green). The squared correlation coefficients and mean squared errors are denoted.45

In many cases, the location of the maximum/minima are generally correct, but the amplitudes of some of the barriers were not in perfect agreement. The ab initio torsion profile assessed for 5-hydroxytryptophan (HTR) and for 1-carboxyglutamic acid (CGU) agreed well with the ff03 potential, and thus did not need to undergo any correction. For the other 10 torsions depicted, it was evident they could benefit from specific torsion corrections. We derived torsion parameters that reproduce the difference between the quantum energy (EQM ) and the AMBER energy in the absence of the CHI torsional parameter which is to be fit ,96

| (1) |

Ecorrection has the form

| (2) |

where is the force constant, γn is the phase shift, and n corresponds to the periodicity.

Since the form of the AMBER dihedral potential energy is a truncated Fourier series, the correction term can naturally be described by the coefficients of a Fourier transform. Given the expected correction is in terms of discrete angle rotations about the torsion being considered, we applied a discrete Fourier transform, calculated using a Fast Fourier Transform algorithm implemented in the R programming language97 to extract the coefficients.

In complex exponential form, the Fourier coefficients98 of a discrete signal can be described as

| (3) |

for which the corresponding inverse transform is

| (4) |

Some manipulation of this equation can lead to a form comparable to that used for the AMBER torsion potential as shown by the following derivation.

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

From the above, the parameters in the AMBER dihedral term can be extracted as −θk = γk and . The FFT procedure was implemented in R with the signal to be fit , returning the corresponding force constants and phase shifts for a prescribed number of terms. The exact conformations used to calculate the QM energies were evaluated for their corresponding AMBER energies, aiming to reproduce the goal of the paramfit procedure95 without needing to solve a nonlinear optimization problem.

Using this approach, as seen in Figure 14, the torsional corrections derived achieved excellent agreement with the QM rotational profiles. The series was truncated with a small number of terms that would achieve sufficiently high agreement with the signal in terms of both correlation and mean squared error. For the success of the FFT approach, it was important that the sampling of the discrete points must be sufficiently large (in our case 72 points were considered), despite its very large computational cost. Another approach would have been to solve for the parameters directly through different nonlinear optimization search routines including simplex algorithms, genetic algorithms, or monte-carlo search as applied by others.94,99,100 This is a highly non-convex problem, although simplifications such as setting the phase shift term to a constant value can reduce the problem to a more tractable least-squares fit of a convex function, as was done by others.

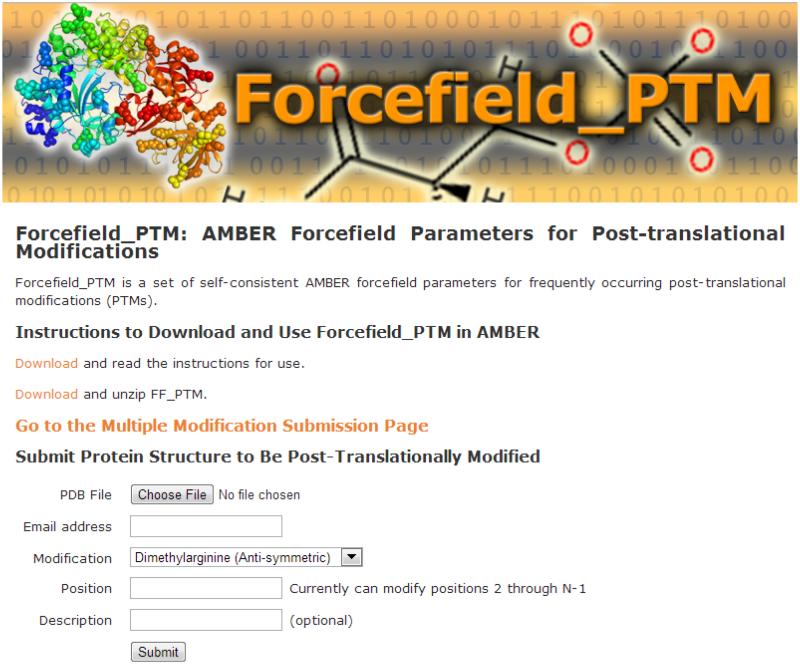

3.6 FF_PTM Webtool

To make FF_PTM more broadly available for use in the academic community, we have created a web interface http://selene.princeton.edu/FFPTM, shown in Figure 15. In the interface, a user can download FF_PTM, as well as read instructions for its use with AMBER directly. Additionally, the interface allows one to upload a PDB structure to be modified by single or multiple post-translational modifications, and/or simultaneously mutated. Once submitted, the tool makes the requested modifications and performs a local energy minimization in AMBER using the parameters from FF_PTM and ff03. The user receives an e-mail notifying them of the structure successfully being modified with a unique link to download their results. The results page contains an interactive interface through Jmol to visualize the structure before and after modification as well as links to information about the structures. Links to download the original and modified structure are provided. The TMScore and RMSD between the structures is calculated by TM-align101 and provided to the user. The webtool also returns to the user an AMBER topology and parameter file (prmtop) and input coordinates (inpcrd) that were generated through tleap and can directly be used as input to further molecular dynamics simulations. The AMBER potential energy corresponding to the locally optimized structure is also provided.

Figure 15.

Web interface for the dissemination of Forcefield_PTM. The webtool has static download links to download and use Forcefield_PTM in AMBER, as well as an interactive interface to make post-translational modifications and mutations to an input PDB structure.

The web interface automatically detects disulfide bridges and enforces them. This interface will be useful to utilize the parameters to interactively make site-specific modifications on a protein structure. This can be applied to protein-protein complexes to understand what interactions the modified side-chains may have in an interface compared to the unmodified side-chains. Additionally, we anticipate the tool will be useful to modify positions on a protein structure to assess the changes in the microenvironment they may cause.

4 Discussion

Inspired by the success, broad applicability, and usage of the AMBER suite of molecular dynamics programs and tools, we have developed FF_PTM, to complement AMBER’s existing forcefield, ff03, and to enable the atomistic study of the structure, dynamics, and design of proteins containing post-translational modifications. FF_PTM focused on deriving parameters for 32 PTMs occurring frequently in nature.32 Several of these modifications, such as the phosphorylated parameters, have also been previously parameterized using different methods for other forcefields derived in the gas-phase, and served as comparisons to the parameters derived in this work. Although a comparison of results derived from condensed-phase simulations with experimental observables such as density, heats of vaporization, free energy energies of hydration, among others, have historically been a key validation test of forcefields such as OPLS39 and AMBER, this data is more difficult to obtain and less standardized than data for the twenty naturally-occurring amino acids, due possibly to the biological reactions required to generate the modified amino acids, and the difficulty of resolving and purifying a single post-translationally modified amino acid.

This paper presents an effort to globally assess the effects of PTMs on secondary and tertiary structures of proteins contained in the PDB by comparing them to their unmodified forms. The distributions uncovered by such a search are interesting, and this tabulated dataset alone can be used for future work by others. Using these identified pairs, we next performed a consistent set of simulations on both small, medium, and large protein structures contained in the PDB, for both their unmodified and modified forms to assess the usability of the new forcefield parameters. We compared secondary and tertiary structure stability, as well as energetic stability for trajectories each of the modified and unmodified structures curated from the PDB. Similar overall trends were observed between the modified and unmodified simulations. For the partial charges derived, we compared to previously published parameters finding strong agreement in all cases as evidenced by a strong correlation coefficient and small mean-squared and sum-squared errors, even though the parameters calculated herein were done in the condensed-phase rather than in the gas phase. By our assessment, the charges calculated in FF_PTM perform well with ff03 in terms of simulation stability. Testing was done to ensure that one can start with an initial PDB structure, import the parameters, and begin the simulation with little to no extra effort. The parameterization effort also served as an independent validation of other PTM parameterization efforts thus far. Finally, key χ torsion parameters contained in side-chains of the PTMs in this work were assessed with respect to their ab initio rotational profiles, and several corrections were developed to achieve excellent agreement between the AMBER-calculated and ab initio relative energies.