Abstract

Extensive evidence documents that prenatal maternal stress predicts a variety of adverse physical and psychological health outcomes for the mother and baby. However, the importance of the ways that women cope with stress during pregnancy is less clear. We conducted a systematic review of the English-language literature on coping behaviors and coping styles in pregnancy using PsycInfo and PubMed to identify 45 cross-sectional and longitudinal studies involving 16,060 participants published between January 1990 and June 2012. Although results were often inconsistent across studies, the literature provides some evidence that avoidant coping behaviors or styles and poor coping skills in general are associated with postpartum depression, preterm birth, and infant development. Variability in study methods including differences in sample characteristics, timing of assessments, outcome variables, and measures of coping styles or behaviors may explain the lack of consistent associations. In order to advance the scientific study of coping in pregnancy, we call attention to the need for a priori hypotheses and greater use of pregnancy-specific, daily process, and skills-based approaches. There is promise in continuing this area of research, particularly in the possible translation of consistent findings to effective interventions, but only if the conceptual basis and methodological quality of research improve.

Keywords: pregnancy, stress, coping, systematic review

Although many women report that pregnancy is a joyful and happy period in their lives, the demands and changes associated with this reproductive period, and the social context within which pregnancy takes place, can produce high levels of stress and anxiety for many expectant mothers. Pregnancy requires many adjustments in physiological, familial, financial, occupational, and other realms which may evoke emotional distress for women, especially women of low-income who are prone to experience more stress with fewer resources (Norbeck & Anderson, 1989; Ritter, Hobfoll, Lavin, Cameron, & Hulsizer, 2000). Pregnant women may also worry about the health of their babies, impending childbirth, and future parenting responsibilities (Lobel, 1998; Lobel, Hamilton, & Cannella, 2008). Stress can be defined as demands appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the individual (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Such demands can be generated or exacerbated by the social environmental context in which pregnancy takes place. For example, the experience of early pregnancy may differ as a function of whether the pregnancy was unplanned or planned, and whether it occurs with or without family support. Variation in stress among pregnant women can be substantial but by all reports, a large proportion of children born today are exposed to high levels of maternal stress during gestation.

Furthermore, increasingly strong evidence points to many negative consequences of stress that occurs in pregnancy. For example, women with high stress are less likely to maintain optimal health behaviors during pregnancy, and they are more likely to smoke and be sedentary (Lobel, Cannella, Graham, DeVincent, & Schneider, 2008; Weaver, Campbell, Mermelstein, & Wakschlag, 2008). Moreover, expecting mothers who experience high stress or anxiety during pregnancy are at risk of preterm birth and giving birth to low birth-weight infants (for reviews see Dunkel Schetter, 2009, 2011; Dunkel Schetter & Glynn, 2010; Dunkel Schetter & Lobel, 2012). Internationally, fifteen million babies are born preterm each year and complications due to preterm birth account for 14% of child deaths under 5 years of age (March of Dimes, PMNCH, Save the Children, & WHO, 2012). These adverse birth outcomes are a pressing public health issue in some countries, such as the United States where the national rates of preterm birth and low birth weight average 13% and 8% respectively (Martin et al., 2010).

Certain maternal characteristics (African-American race, low socioeconomic status, and medical conditions such as infections during pregnancy) are associated with the occurrence of adverse birth outcomes. Yet sociodemographic and biomedical approaches alone have not sufficiently identified those women who later deliver their babies too small or too soon (Lu & Halfon, 2003), which has led to the development of multilevel models (Dunkel Schetter & Lobel, 2012; Misra, Guyer, & Allston, 2003) and greater focus on psychosocial risk and resource factors including stress exposure. Traumatic events including nuclear disasters, terrorist attacks, hurricanes, earthquakes, or floods when they occur during pregnancy have been associated with poorer pregnancy outcomes (Glynn, Wadhwa, Dunkel-Schetter, Chicz-DeMet, & Sandman, 2001; Lederman et al., 2004; Xiong et al., 2008), as have major life events like job loss, the death of a family member when they occur just preceding pregnancy or during gestation (Hedegaard, Henriksen, Secher, Hatch, & Sabroe, 1996; Messer, Dole, Kaufman, & Savitz, 2005; Whitehead, Hill, Brogan, & Blackmore-Prince, 2002). Other studies examining the impact of life events, stress appraisals, or perceived stress have often also shown adverse effects on birth outcomes (Dole et al., 2003; Zambrana, Dunkel-Schetter, Collins, & Scrimshaw, 1999). Furthermore, accumulating evidence points to pregnancy-related anxiety as particularly potent in effects on mothers and their offspring (DiPietro, Hawkins, Hilton, Costigan, & Pressman, 2002; Huizink, Robles de Medina, Mulder, Visser, & Buitelaar, 2002b; Lobel, Cannella, et al., 2008; Mancuso, Dunkel-Schetter, Rini, Roesch, & Hobel, 2004; Orr, Reiter, Blazer, & James, 2007). In a large prospective cohort study of preterm birth, Kramer et al. (2009) utilized numerous stress and distress measures, and found that only pregnancy-related anxiety was consistently and independently associated with spontaneous preterm birth. The fact that the association persisted after adjustment for medical and obstetric risk factors, perceptions of pregnancy risk, and depressed affect, suggests that the risk is not due to anxiety caused by one’s medical risk factors alone and has other origins. Because pregnancy anxiety and stress have been linked to adverse birth outcomes, understanding how women cope with stress in pregnancy, and especially with pregnancy-specific concerns such as impending labor and delivery, infant health, and parenting, is of paramount importance. It may offer an opportunity to influence pregnancy, birth and later infant and maternal outcomes (Alderdice, Lynn, & Lobel, 2012). Perhaps for this reason, studies of stress and coping in pregnancy have proliferated.

The good news is that not every woman who experiences a major life event or faces chronic strain during pregnancy gives birth to a preterm or low birth weight infant or one with developmental adversities. Why do some women fare better than others when confronted with stressors during pregnancy? A resilience approach may shed light on this important issue (Zautra, Hall, Murray, & the Resilience Solutions Group, 2008). For example, variability in coping behavior and in coping efficacy or skill should contribute to differences in the psychological and physiological effects of stress exposure during pregnancy (Dunkel Schetter, 2011; Dunkel Schetter & Dolbier, 2011). Thus, a review of what we know and do not know about coping in pregnancy seemed worth doing.

Conceptual Background in Stress and Coping Theory

Coping is defined as constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts aimed at dealing with the demands of specific situations that are appraised as stressful (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). In the context of pregnancy, coping efforts may influence birth outcomes by serving to minimize or prevent negative emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and physiological responses to stressors. As a result, the ability to select and implement an appropriate coping response could serve as a resilience resource that buffers expectant mothers and their children from the potentially harmful effects of prenatal stress exposure. For example, those who cope by seeking emotional support or taking action to resolve the problem may have fewer deleterious effects of stress, whereas those who avoid dealing with the stressor or engage in adverse health behaviors such as smoking to reduce distress would have heightened vulnerability. Indeed, a large epidemiological study of 1,898 African-American and White women in North Carolina found that avoidant coping styles were associated with an increased risk of preterm delivery (Dole et al., 2004; Messer et al., 2005), fueling our examination of coping during pregnancy.

As prolific leaders in the study of stress and coping, Lazarus and Folkman (1984) defined stressors as demands that are appraised as personally significant and as taxing or exceeding the resources of the individual. According to this cognitive approach to the study of stress, how a woman appraises events during her pregnancy may shape her emotional and behavioral responses, and influence how she copes. Although dominant conceptions define coping as cognitive and behavioral attempts to manage a particular situation, usually labeled coping behavior (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), a few researchers have been interested in coping styles, which refers to more consistent tendencies to cope in particular ways such as through approach or avoidance (Miller, 1987; Steptoe & O’Sullivan, 1986). This alternate conception treats coping as a relatively stable trait and contrasts with the contextual approach to coping, which views coping processes as situation specific and dynamic (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

In describing specific coping efforts and more general coping styles, theorists have traditionally distinguished between problem-focused and emotion-focused coping. Problem-focused coping is aimed at the stressor itself, and may involve taking steps to address or resolve the situation. It is most frequently used when the stressor is something an individual appraises as controllable. Emotion-focused coping, in contrast is aimed at reducing feelings of distress associated with stressful experiences, and is more likely to be used if the person views the stressor as uncontrollable (Carver, 1997; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Researchers may also distinguish between approach or engagement coping, referring to efforts aimed at dealing with the stressor itself, either directly or indirectly, as compared to avoidance or disengagement coping which refers to efforts to escape from having to deal with the stressor (Roth & Cohen, 1986; Suls & Fletcher, 1985). Avoidance coping is usually thought of as a form of emotion-focused coping because it may involve attempts to evade or escape from the feelings of distress associated with the stressor (Carver, 2007). These binary classification systems aggregate many theoretically distinct ways of coping and thereby may be obscuring the nature of relationships between specific coping behaviors and various dependent variables, but they have been utilized frequently in the literature and yielded some useful findings.

Purpose and Hypotheses

Given a strong theoretical and sufficient empirical basis for research on coping in pregnancy, we conducted a systematic review of studies examining coping in the context of pregnancy. The goals were to (a) describe and methodologically critique the published studies on coping by pregnant women; (b) identify key findings that emerge from this collection of studies; (c) situate this review within the context of the larger literature on stress and coping theory, with particular attention paid to the possible moderating role of coping behaviors and styles; and (d) to consider how the field can move forward in the study of how pregnant women manage stress with an ultimate goal of better assisting women who experience significant demands during pregnancy.

We expected that the findings would be strongest or least equivocal when examining the most methodologically rigorous studies – that is, those with theoretically-grounded a priori hypotheses tested in sufficiently large samples sizes using well-validated measures of coping and outcome measures. Based on coping theories that emphasize contexts in which stress occurs, we also anticipated that the strongest findings would be in studies that examined how women cope with specific stressors experienced during their pregnancies as compared to studies of general coping styles or coping behaviors.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature from January 1990 to June 2012 was conducted using PsycInfo and PubMed. Empirical investigations on coping in human pregnancy were located by searching PsycInfo using the search terms all(coping) AND all((pregnan* OR prenatal)) and limiting results to scholarly journals or books, human populations, English language, and publication dates January 1990 and June 2012. We also searched PubMed using “Pregnancy”[Mesh] AND “coping”[All Fields] AND ((“1990/01/01”[PDAT]: “2012/06/30”[PDAT]) AND “humans”[MeSH Terms] AND English[lang]). Because of the unique stressors associated with adolescent pregnancy, we limited our review to studies conducted in adult populations (over 18 years of age).. Searches for publications of researchers known to study coping during pregnancy were completed, and lists of citations for all retrieved articles were examined to locate additional studies meeting inclusion criteria. This search yielded papers published in peer-reviewed journals with null findings; thus, we were not particularly concerned about publication bias and excluded unpublished dissertations and studies. All papers were abstracted to characterize samples, methods, and major findings and classified according to study design and objectives, with cross-sectional studies described first (Supplementary Table 2), followed by longitudinal studies that are further categorized by outcome variable as follows: prenatal psychological outcomes (Supplementary Table 3), postpartum psychological outcomes (Supplementary Table 4), biological, birth, and infant development outcomes (Supplementary Table 5). The coauthors independently conducted searches and abstracting; the few discrepancies were resolved by discussion until a consensus was reached. When necessary, we contacted authors of papers with insufficient or unclear information for clarification of study methods and results. Because our goal was to review and evaluate evidence on associations of coping to psychological and physical health outcomes, we also excluded papers that tested only the antecedents (e.g. race, education) or concomitants (e.g. spirituality) of coping (Balcazar, Peterson, & Krull, 1997; Balcazar, Krull, & Peterson, 2001; Borcherding, 2009; Mahoney, Pargament, & DeMaris, 2009; Ortendahl, 2008).

Results

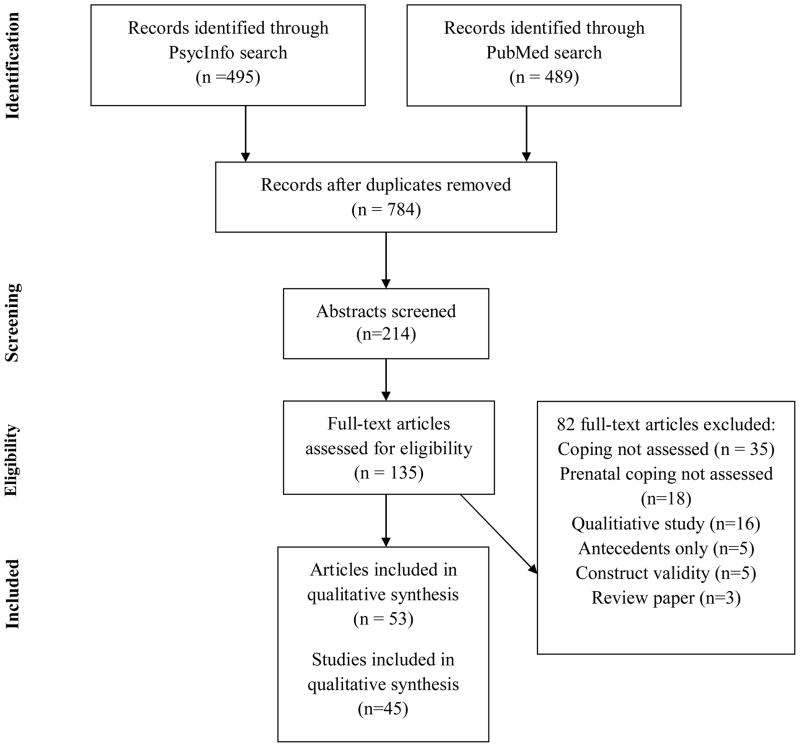

In total, we identified 45 studies and 53 publications meeting inclusion criteria (see Figure 1). Sample sizes ranged from 30 participants (Mikulincer & Florian, 1999) to 2,761 participants (Tiedje et al., 2008) and timing of assessments ranged from very early in pregnancy (4 weeks gestation) to post-term (41 weeks). Studies were conducted in geographic regions including Europe, North America, Asia, and Australia. Although all of these studies utilized convenience samples predominantly recruited from childbirth preparation classes or prenatal clinics, some studies recruited samples of low-income, minority women that are typically underrepresented in health research (e.g. Borders, Grobman, Amsden, & Holl, 2007; Rodriguez et al., 2010), or large and diverse samples more reflective of the populations under study (e.g. Dole et al., 2004; Tiedje et al., 2008). We report the measure used to assess coping in each paper, as well as how the measure was used because there was some variability in the instruction sets across studies. For example, some studies asked participants to report their general coping styles (n=19), others assessed coping behaviors during pregnancy (n=7), still others assessed coping with pregnancy-related stressors (n=15), and a few assessed coping skills (n=6). We also present a count for each paper of the number of statistically significant findings out of the total tests conducted (or eligible for testing based on the product of the number of ways of coping assessed and the number of dependent variables included in analyses).

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram

Coping Instruments and Measures

Before discussing the findings, we describe briefly the instruments used. We identified a total of 22 different measures used in the literature to assess coping during pregnancy (see Supplementary Table 1). Studies of how women cope with stress during pregnancy have typically employed a generic coping instrument intended for use in the general population, but have sometimes designed or adopted a pregnancy-specific coping questionnaire, or used a measure of general coping skills.

General measures of coping behavior and style

As shown in Supplementary Table 1, there is a great variability in the generic instruments used to assess coping during pregnancy, as well as in the number and types of subscales included in each measure. Fourteen different coping measures that were developed for the general population have been used in the pregnancy studies. None of the papers presented findings concerning convergent and discriminant validity of these general measures for use in pregnancy, although they often referred the reader to the original publication for further information about the measure’s validity and reliability in the general population. The most commonly used of these measures are the Ways of Coping (WOC; Folkman & Lazarus, 1988), the COPE (Carver, 1997) and the Brief COPE (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989), all of which are well-validated for use in the general population. When Cronbach’s alphas are reported for the subscales of these measures, they indicated acceptable reliability during pregnancy in general (Gotlib, Whiffen, Wallace, & Mount, 1991; Honey, Morgan, & Bennett, 2003; Levy-Shiff et al., 2002; Lowenkron, 1999; Mikulincer & Florian, 1999; Pakenham, Smith, & Rattan, 2007; Soliday, McCluskey-Fawcett, & O’Brien, 1999). Another validated general coping measure that has been used in a number of large studies of birth outcomes is the John Henryism Coping Scale (James, Hartnett, & Kalsbeek, 1983), which assesses the extent to which individuals attempt to actively control behavioral stressors through hard work and determination. However, reliability coefficients for this scale were not reported for any of the pregnancy studies using this measure. Two studies used the Miller Behavioral Style Scale (Miller, 1987), which assesses coping behaviors by asking participants how they would likely cope with four hypothetical uncontrollable stressful situations, such as a fear of flying.

There is also variation in whether these general coping measures were used to assess coping behaviors (efforts) or styles. In most studies, participants were asked to report how they generally cope with stress in order to assess coping traits or dispositional coping styles, rather than to indicate cognitive or behavioral efforts to manage specific stressful situations. In this format, participants were typically asked to report the extent to which they tended to respond in certain ways to stress in general, or to stress during pregnancy. Alternatively, researchers might ask participants to situate their responses within the context of pregnancy and to report the ways in which they tended to cope with pregnancy demands over a specified period of time such as during the current trimester. A few researchers asked participants to respond to generic coping inventories with respect to specific stressors encountered during pregnancy. For example, pregnant women in one study were asked to think about a stressful event that occurred over the previous two months and report how frequently they used each strategy in attempting to cope with the stressor (Spirito, Ruggiero, Bowen, & McGarvey, 1991). Thus, there is remarkable range in how general coping instruments have been used in pregnancy.

Measures of coping skills

A small number of studies assessed coping skills rather than specific coping styles or behaviors. As individuals have different levels of skills for responding to life’s challenges and demands, these studies are concerned with understanding the effects of an individual’s perceived ability to deal with stress. For example, Borders et al. (2007) measured coping skills using the State Hope Scale (Snyder et al., 1996), an instrument that includes items such as “if I should find myself in a jam, I could think of many ways to get out of it” and “there are lots of ways around any problem that I am facing right now.” However, other items on the scale such as “right now, I see myself as being pretty successful” and “at this time, I am meeting the goals I have set for myself” may reflect other concepts and not coping skills per se. A Cronbach’s alpha coefficient would indicate the internal consistency of this scale but it was not reported, nor was any other construct validity information. Two additional studies assessed participants’ appraised resources to deal with stress using the Stress Coping Inventory (Ryding, Wijma, Wijma, & Rydhstrom, 1998; Soderquist, Wijma, Thorbert, & Wijma, 2009). This unvalidated measure asks participants to rate how able they are to cope with 41 different stressful situations. These studies are reviewed in detail below, but the measures of coping skills used were each designed to assess something else (i.e., hope, self-efficacy, sense of coherence), which raises questions about the meaning of the results.

Coping measures developed specifically for pregnancy

In contrast to adopting generic coping instruments and adapting them to pregnancy or using a general coping skills measure, Yali and Lobel (1999) developed a pregnancy-specific measure, the 36-item Prenatal Coping Inventory (PCI). This instrument is designed to capture coping behaviors that are specific to stressors encountered by pregnant women (e.g. “prayed that the baby will be healthy,” “felt lucky to be a woman to experience pregnancy,” and “asked doctors or nurses about the birth”). Women are asked to report how often they used each method of coping “to try to manage the strains and challenges of being pregnant” during a given time frame on a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (almost always). In the first published report utilizing this scale, Yali and Lobel (1999) identified four internally-consistent coping subscales in a sample of 167 medically high-risk women assessed at mid-pregnancy: (1) Preparation for motherhood (8 items; e.g. “planned how you will handle the birth”, α =0.83), (2) Avoidance (6 items; e.g. “avoided being with people in general”, α=0.75), (3) Positive Appraisal (5 items, e.g. “felt that being pregnant has enriched your life”, α =0.80), and (4) Prayer (2 item; e.g. “prayed that the birth will go well”, r= 0.74). These same four stable, internally consistent factors were also found by factoring a 42-item version called the Revised Prenatal Coping Inventory (NuPCI) developed for use in the repeated assessment of coping strategies over the course of pregnancy (Yali & Lobel, 2002). Based on a review of the questionnaire items, the acceptable reliability coefficients, and patterns of correlations with related constructs (e.g. distress, optimism) obtained in studies using these pregnancy-specific instruments, the PCI and NuPCI appear to be reliable and valid.

Cross-Sectional Studies of Coping

As shown in Supplementary Table 1, we located 25 cross-sectional studies that assessed coping in the context of pregnancy. We describe these studies below, providing summaries of findings related to direct and moderated effects of coping on physical and mental health.

Mental and physical health associations

The most consistent set of findings are on avoidant coping styles or behaviors. These have been associated with many adverse mental health outcomes in pregnancy including lower general psychological well-being, increased distress, higher depressed mood, more anxiety, higher perceived stress, less positive attitudes towards cystic fibrosis screening, and greater child abuse potential (Faisal-Cury, Savoia, & Menezes, 2012; Fang et al., 2007; Giurgescu et al., 2006; Hamilton & Lobel, 2008; Lobel et al., 2002; Lowenkron, 1999; Rodriguez, 2009; Rudnicki, Graham, Habboushe, & Ross, 2001; Spirito et al., 1991) as well as physical health correlates such as greater daily glucose variability among women with gestational diabetes (Spirito et al., 1991). Latendresse and Ruiz (2010) also found that a general avoidant coping style was associated with higher maternal levels of corticotrophin-releasing hormone of placental origin (pCRH), which has been implicated in the timing of delivery and etiology of preterm birth (Challis et al., 2000; Mancuso et al., 2004; McLean et al., 1995; Sandman et al., 2006). Substance use is another potentially harmful means of coping with stress during pregnancy. In one study, coping with pregnancy through alcohol or tobacco use was associated with greater pregnancy-related distress and prenatal depression (Yali & Lobel, 1999), whereas coping by using tobacco to deal with emotions or problems was associated with greater risk of continuing to smoke during pregnancy (Lopez, Konrath, & Seng, 2011).

By contrast, some coping responses have been linked to indicators of more favorable psychological well-being. Coping with pregnancy through positive appraisal -- which involves efforts to create positive meaning by focusing on personal growth -- has been associated with better maternal attachment, fewer depressive symptoms, and lower global and pregnancy-related distress (Pakenham et al., 2007; White et al., 2008; Yali & Lobel, 1999). Furthermore, in a recent study of 230 predominantly low-income women enrolled in a program for pregnant smokers, a specific type of spiritual coping style focused on surrendering one’s problems to God was associated with lower levels of stress during pregnancy (Clements & Ermakova, 2012). The results of this small set of studies suggest that coping efforts involving positive appraisal or religious faith are associated with better psychological adjustment during pregnancy.

The findings of studies measuring problem-focused coping in pregnancy are mixed. Three studies found that problem-focused coping styles, such as problem-solving, planning and preparation, are associated with greater pregnancy-related distress (Faisal-Cury et al., 2012; Hamilton & Lobel, 2008; Yali & Lobel, 1999), whereas a fourth found that active coping styles were associated with fewer depressive symptoms (Wells, Hobfoll, & Lavin, 1997). John Henryism, an effortful coping style, has been linked to greater likelihood of exercise during pregnancy among African-American pregnant women (Orr, James, Garry, & Newton, 2006), but it was also more strongly associated with bacterial vaginosis than any other stress-related measure in 1,587 pregnant women in North Carolina (Harville, Savitz, Dole, Thorp, & Herring, 2007). The results of the latter study suggest a link between coping processes and immune function, although this association was no longer statistically significant in analyses that controlled for age, income, and race.

In sum, consistent with findings in the larger coping literature, avoidant coping styles and behaviors appear to be associated with psychological distress, whereas active problem- and emotion-focused styles and behaviors are generally, although not entirely consistently, associated with indicators of well-being.

Moderated effects

Most extant studies have examined the direct effects of maternal coping on physical or mental health outcomes and not tested moderation. However, conceptual approaches found in the broader coping literature that emphasize coping as a moderator of the effects of stressors on health suggests it would be beneficial to test this in research on coping with stress during pregnancy.

Only three cross-sectional studies sought to test stress-moderating effects of coping (Pakenham et al., 2007; Spirito et al., 1991; Wells et al., 1997). Within a sample of 242 first-time mothers in Australia, Pakenham and colleagues (2007) found an association between pregnancy-related threat appraisal and depression during the third trimester of pregnancy only among women who reported high wishful thinking to cope with pregnancy-related stress. Another study of 92 pregnant women also found only limited evidence of a stress-moderating effect of coping. Drawing on Conservation of Resources Theory (Hobfoll, 1988; Hobfoll, 1989), Wells and colleagues (1997) found that greater stress, which was operationalized as recent setbacks in domains including childcare, employment, marriage, and daily routine, was associated with greater depression only if the participant did not report a cautious action coping style. There were no other interactions between coping styles and resource loss in predicting depression, and no evidence that any of the coping strategies buffered the effect of resource loss on anger. Finally, Spirito and colleagues (1991) examined the correlates of engagement (including problem-solving, cognitive restructuring, social support and emotional expression) and disengagement coping behaviors (avoidance, wishful thinking, self-criticism and social withdrawal). The authors did not find evidence to support their hypothesis that active coping with a recent stressor would be more strongly associated with well-being in the women who were dealing with the unexpected health-related stressor of diabetes versus those who were not. Taken together, the lack of significant interactions between stress and coping in these three studies does not support the hypothesis that coping modifies or buffers the association of stress with mental health outcomes.

Summary of cross-sectional studies

In summary, almost half of the total number of coping studies that we identified had cross-sectional designs that provided data only on the frequency and correlates of different coping strategies or styles in pregnancy. Although coping through avoidance was associated with several indicators of poor psychological well-being, conclusions about the causality of these effects cannot be drawn. For example, an avoidant coping style may lead to disengagement with one’s social environment and contribute to the onset of depressive symptoms during pregnancy or postpartum, or a depressed pregnant women may be more likely to cope through avoidance because of the low energy and negative affect associated with depression. Third variable causation is also possible. The longitudinal studies reviewed in the following section address some of these questions regarding directionality of effects.

Longitudinal Studies of Prenatal Coping

Twenty-eight longitudinal studies examined the effects of how women cope with stress during pregnancy (see Tables 2 through 4). These studies explored: (a) how coping changes over the course of pregnancy, (b) effects of coping at one time point on adjustment later in pregnancy, (c) effects of coping during pregnancy on postpartum outcomes, and (d) effects of coping on biological, birth and infant development outcomes.

Longitudinal studies on psychological outcomes during pregnancy

One study examined whether coping during early pregnancy predicted affective states later in pregnancy (Huizink et al., 2002a). Although this study replicated associations between coping and concurrent distress found in the cross-sectional studies described above, there was no evidence that coping predicted psychological outcomes later in pregnancy when controlling for baseline distress. Three longitudinal studies explored general coping styles in the context of prenatal testing, a potentially threatening experience in pregnancy because such tests can reveal abnormalities in the developing fetus (Tercyak et al., 2001; Van Zuuren, 1993; Zlotogorski et al., 1995). However, none of these three studies found significant effects of coping style on subsequent psychological distress. Taken together, this set of five studies provides surprisingly little evidence to support the hypothesis that coping styles or behaviors predict psychological distress later in pregnancy.

Coping as a predictor of postpartum mood

Does the way that a woman copes with stress during pregnancy have implications for her mood after birth? The largest of the studies that sought to answer this question included 730 pregnant women who completed the Ways of Coping questionnaire with respect to a recent stressor of their choosing and were assessed for depressive diagnostic status at 23 weeks gestation and at 4.5 weeks postpartum (Gotlib et al., 1991). After controlling for depressive symptoms during pregnancy, none of the eight WOC subscales predicted recovery from prenatal depression or onset of depression during the postpartum.

In contrast to these null findings, two other prospective studies (see Supplementary Table 3) found that women who reported avoidant coping styles during pregnancy were at heightened risk for postpartum depression. Among 306 pregnant women giving birth for the first time, avoidant coping style assessed during the last trimester predicted higher depressive symptoms at approximately 6 weeks postpartum, controlling for history of depression (Honey, Morgan, et al., 2003). The association between avoidant coping style during pregnancy and postpartum depressive symptoms was also documented in a study of 210 pregnant Latinas, a majority of whom were affected by intimate partner violence (Rodriguez et al., 2010). Avoidant coping style predicted depressive symptoms over time in a multivariate repeated measures mixed effects model, suggesting that the women who cope through avoidance during pregnancy face a heightened risk of postpartum depression.

Avoidant coping may negatively affect postpartum mood; in contrast, active, problem-focused forms of coping during pregnancy have been associated with both lower (Besser & Priel, 2003; Morling, Kitayama, & Miyamoto, 2003) and higher levels (Soliday, McCluskey-Fawcett, & O’Brien, 1999) of postpartum depression. However, the two studies that found an inverse relationship between active coping and postpartum depressive symptoms both suggest that active coping may only be helpful for certain individuals (Besser & Priel, 2003; Morling et al., 2003). In a study conducted with a sample of 146 Israeli women having their first births (Besser & Priel, 2003), approach-oriented coping (measured by a Hebrew version of the Ways of Coping questionnaire) “with pregnancy-related problems” during the third trimester predicted reduced depressive symptoms postpartum but only among “self-critical” participants. Cultural context may also modify the effectiveness of active coping attempts. Morling et al. (2003) explored coping strategies used by 94 Japanese and 56 American pregnant women in response to common pregnancy concerns such as the baby’s health and well-being, their relationship with their partner, their labor and delivery, and the amount of weight they were gaining in pregnancy. For American women, higher acceptance correlated with less distress over time, better prenatal care, and less weight gain, but these results did not hold for Japanese women.

Finally, a small but interesting set of studies examined the impact of coping skills or coping efficacy on psychological adjustment during the postpartum period. These studies assessed participants’ perceived ability to effectively deal with stress and negative emotions, rather than particular types of coping behavior. Four of these studies addressed the characteristics of the small proportion of women who suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or post-traumatic stress symptoms following a difficult experience of childbirth, an topic of growing interest in clinical research (Olde, van der Hart, Kleber, & van Son, 2005). In the largest of these three studies with a sample of 1224 women in Sweden, low levels of perceived coping ability during early pregnancy were associated with increased risk of elevated PTSD symptoms at one month postpartum (Soderquist et al., 2009). Poor coping skills during pregnancy were also associated with increased risk of postpartum post-traumatic stress in three other studies (Borders et al., 2007; Ford, Ayers, & Bradley, 2010; Soet et al., 2003).

In sum, 13 studies attempted to establish associations between coping styles during pregnancy and postpartum psychological states but variation in the samples, coping measures, outcome variables, and timing of assessments makes it difficult to draw conclusions. As was the case in the cross-sectional studies, the most consistent set of findings are those that document a relationship between greater avoidant coping and greater psychological distress. Four studies report that poor coping skills during pregnancy predicted post-traumatic stress symptoms during the postpartum period. However, coping skills were assessed with a wide variety of measures originally developed to operationalize hope, sense of coherence, and self-efficacy, which makes it impossible to determine whether these effects are actually due to coping skills or to other related but distinct psychological resources.

Coping and biomarkers during pregnancy

As shown in Supplementary Table 4, two large studies explored associations between active, effortful coping and levels of maternal pCRH. Neither of these studies found a relationship between participants’ scores on the John Henryism Active Coping Scale, which assesses the extent to which individuals attempt to actively control behavioral stressors through hard work and determination, and levels of pCRH or cortisol measured during pregnancy (Chen et al., 2010; Harville, Savitz, Dole, Herring, & Thorp, 2009). In a third study with measures of blood pressure, no relationship was found between John Henryism and maternal vascular functioning (Tiedje et al., 2008). In sum, we did not locate any evidence of significant associations between coping style and physiological markers during pregnancy.

Coping as a predictor of birth outcomes

As noted, an epidemiological study called the Pregnancy, Infection, and Nutrition (PIN) study provides among the strongest evidence that coping in pregnancy is important to study by showing an association with birth outcomes. Dole and colleagues (2004) found a prospective association between general use of distancing and avoidant coping mechanisms as reported on the Ways of Coping questionnaire and preterm delivery in 724 African-American and 1174 White women. Interestingly, these associations varied by race, with African-American women who distanced from problems having modestly higher risk of preterm birth than women with lower use of this strategy whereas White women had an increased risk for preterm birth when they were either moderately or very likely to cope with problems through escape/avoidance. Thus, this one large epidemiological study indicates that the coping behaviors of pregnant women are associated with the timing of delivery but these associations may vary by race. In a much smaller study of 80 married pregnant women in Canada, women who reported greater distractive coping style had more labor and delivery difficulties, whereas emotional coping during the second trimester was associated with larger infant birth weight (Da Costa, Drista, Larouche, & Brender, 2000). However, another large study of 2,761 non-Hispanic White and African-American pregnant women did not find a relationship between effortful coping during pregnancy and preterm delivery in multivariate analyses (Tiedje et al., 2008). There are too many differences among these few studies to be certain why effects differ.

Coping skills may also be related to pregnancy outcomes. Poor coping skills, as assessed using the State Hope Scale during pregnancy, were associated with low birth weight in a sample of 294 welfare recipients (Borders et al., 2007). Furthermore, a retrospective study of 97 Swedish women who delivered by emergency Cesarean section reported poorer coping abilities at 32 weeks gestation compared to 194 women who did not experience delivery complications (Ryding et al., 1998). The findings of this set of studies suggests that women who have poor coping skills or use avoidant coping strategies may have a higher risk of experiencing adverse pregnancy outcomes but more research is needed.

Coping as a predictor of infant development

As shown in Supplementary Table 5, two studies conducted by Levy-Shiff and colleagues (Levy-Shiff, Dimitrovsky, Shulman, & Har-Even, 1998; Levy-Shiff, Lerman, Har-Even, & Hod, 2002) explored the effects of prenatal coping on infant developmental outcomes. The earlier study of 140 first-time mothers examined the effects of stress and coping in pregnancy and the postpartum period on adjustment to parenthood and infant development (Levy-Shiff et al., 1998). Increases in problem-focused coping efforts from pregnancy to one month postpartum predicted better maternal adjustment to parenting, including enhanced maternal well-being, parenting efficacy, caregiving behaviors, and affiliative behaviors. The second study by this team evaluated coping responses to pregnancy-related stress using the Ways of Coping checklist in a sample of 153 pregnant Israeli women who had pregestational diabetes, gestational diabetes, or were non-diabetic (Levy-Shiff et al., 2002). Greater use of problem-focused coping strategies during pregnancy was associated with better infant cognitive development at one year of age, as measured by scores on the Mental Development Index of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development – 2nd Edition (Bayley, 1993), whereas emotion-focused coping was unrelated to infant development. Furthermore, pre-gestational and gestational diabetic mothers’ use of problem-focused coping strategies during pregnancy predicted infant psychomotor development (assessed by the Psychomotor Development Index of the BSID-II) at one year postpartum, whereas no relationship was found in the non-diabetic group. The results of this interesting study indicate that use of particular coping strategies may be particularly important in the context of high risk pregnancies. Women who are coping with the additional stressor of a medical risk condition requiring extensive management through a regimen of health behaviors (e.g. diet restriction, medication adherence) appear to use different coping strategies with different consequences at least for diabetes risk where the stressor is amenable to problem-focused strategies.

Summary of longitudinal studies of coping in pregnancy

In reviewing the 35 longitudinal studies conducted to date, the largest portion of this literature was composed of the seven studies that examined the effects of prenatal coping on maternal psychological adjustment later in pregnancy (see Supplementary Table 2) and the 17 studies that examined the effects of prenatal coping on maternal psychological adjustment during the postpartum period (see Supplementary Table 3). Only four studies examined the prospective effects of coping during pregnancy on infant birth weight or gestational age at delivery (Borders et al., 2007; Dole et al., 2004; Messer et al., 2005; Tiedje et al., 2008). There were also two studies on infant development (Levy-Shiff et al., 1998; Levy-Shiff et al., 2002), and two studies on maternal biological markers relevant to infant health (Chen et al., 2010; Harville et al., 2007).

In general, the most consistent evidence from methodologically sophisticated longitudinal studies lead to the conclusion that coping behaviors directed at avoiding or distancing from stressors have negative consequences for maternal and child health including evidence regarding preterm birth and postpartum depression (Dole et al., 2004; Gotlib et al., 1991; Honey, Morgan, et al., 2003; Messer et al., 2005). Poor coping skills during pregnancy were also associated with an increased risk of low birth weight (Borders et al., 2007), delivery by emergency caesarean section (Ryding et al., 1998) and maternal posttraumatic stress during the postpartum (Ford et al., 2010; Soderquist et al., 2009). However, these results were not replicated consistently across studies since we located several papers reporting null effects (Chen et al., 2010; Da Costa, Larouche, Dritsa, & Brender, 2000; Harville et al., 2009; Soet et al., 2003; Tercyak et al., 2001; Tiedje et al., 2008; Yali & Lobel, 2002).

One explanation for the inconsistent effects across studies is the variability in study methods that we observed such as differences in sample characteristics, timing of assessments, outcome variables, and measures of coping styles or behaviors. The ramifications of the large amount of variability in research methods are particularly evident when coping strategies are operationalized differently across studies and are then given the same label, such as in the assessment of emotion-focused coping. For example, items labeled emotion-focused coping in study by Huizink and colleagues (2002a) concerned emotional expression and support seeking, whereas the items from the Ways of Coping questionnaire used by Cote-Arsenault (2007) for emotion focused coping relate to avoidance, self-blame, and wishful thinking. This inconsistency is an example of how the same label may be applied to very different sets of coping behaviors, contributing to difficulties in making sense of results and comparing them across studies.

Commentary and Recommendations

Despite over 50 published studies on how adult pregnant women cope, more and better research needs can be conducted to gain a better understanding of the issues. Among the tasks are that we need to delineate the types of stressors that are most relevant to women during pregnancy, consider how distinct subgroups of women cope most effectively with those particular sources of threat or challenge, verify the replicable effects of particular ways of coping, coping styles or skills, and then examine the mechanisms underlying any effects on maternal and child health. In the remainder of the paper, we offer some recommendations for approaching some of the conceptual issues, namely: (a) discrepancies between stress and coping theories and the methodologies used to test them in pregnancy, (b) the importance of viewing pregnancy as a unique health context, and (c) possible applications of descriptive research for interventions.

Specifying A Priori Hypotheses

A major concern that emerged in this review stems from the large number of independent and dependent variables included in many of the studies of coping during pregnancy. Many researchers utilized coping measures with numerous subscales, and also examined multiple outcome variables but without specifying any a priori hypotheses about the variables. If participants’ scores on each of the coping subscales were then tested for an association with all of the dependent variables, the total number of tests was often very large and researchers rarely corrected for number of tests conducted. Indeed, as shown in Tables 2 through 5, the number of tests performed in any given study ranged as high as 28. Testing such a large number of associations increases an investigator’s chances of obtaining at least one significant finding by chance and inflates the probability of Type I errors. We recommend that researchers utilize theory and existing research to formulate a priori hypotheses relating specific ways of coping to specific outcomes and in specific populations. This approach will also reduce participant response burden because interviews or questionnaires could be limited to the coping strategies that test the hypotheses of greatest interest to the researcher, and may also yield more useful results.

Ecological Momentary Assessment and Daily Process Designs

In general, the studies included in this review focused on between-person rather than within-person differences in coping responses, and rarely explored the dynamic nature of coping efforts over time. However, stress researchers working in other contexts are showing greater interest in daily and even momentary assessments of coping efforts (Tennen, Affleck, Armeli, & Carney, 2000). Daily process designs, including daily diary recordings (Stone, Lennox, & Neale, 1985), ecological momentary assessment (Stone & Shiffman, 1994), and experience sampling (Csikszentmihalyi & Larson, 1987) have proliferated in recent years and have begun to yield valuable insights into the complex and dynamic associations between coping efforts, mood, and physical health outcomes in samples of individuals with chronic pain, for example (e.g. Carson et al., 2006; Conner et al., 2006; Litt, Shafer, & Napolitano, 2004; Tennen, Affleck, & Zautra, 2006). Yet, these daily process approaches have not yet made their way into the pregnancy literature with the exception of two studies, each of which demonstrated that an EMA-based measure of negative affect completed in pregnancy was associated with higher salivary cortisol concentrations throughout the day, but neither measured coping efforts (Entringer, Buss, Andersen, Chicz-DeMet, & Wadhwa, 2011; Giesbrecht, Campbell, Letourneau, Kooistra, & Kaplan, 2012). Although daily or momentary coping assessments can be expensive methodologies, they could be a fruitful direction for pregnancy research. They are most appropriate for use in samples of highly motivated study participants who are comfortable with using technology, but pregnant women often have to self-monitor other aspects of their condition and most are highly motivated to have healthy pregnancies so they offer potential for future research.

Skills-Based Approaches

Because the effectiveness of a particular coping strategy depends on the stress context in which attempts are enacted, it is difficult to study coping in general and in pregnancy specifically. Focusing on a person’s coping skills or coping resources may be a more useful direction of study. Measures such as the Coping Self-Efficacy Scale (Chesney, Neilands, Chambers, Taylor, & Folkman, 2006), developed to study the effects of a Coping Effectiveness Training (CET) intervention for depressed HIV-seropositive men with depressed mood, might be useful to pregnancy researchers. This 26-item measure asks respondents about their degree of confidence that they can perform certain behaviors relevant to adaptive coping such as finding solutions or seeking support from friends and family. Our research team has recently developed a measure of coping skills similar to this for use in a large-scale prospective study of a diverse sample of women and it is administered during an inter-pregnancy interval along with pregnancy specific coping measures during the subsequent pregnancy.

Context-Specific Approaches

One of the most prominent methodological weaknesses in the studies reviewed is the use of research methods and designs that do not address the context of pregnancy as it shapes stressors and the nature of efforts to cope with stress. This neglect of the contextual and transactional nature of stress and coping is not unique to pregnancy coping research. As noted by Somerfield and McCrae (2000), a common criticism of the broader coping literature centers on “the gap between the elegant transactional, process theories of stress and adaptation and the methodology of coping research” (p. 621). These transactional theories emphasize that coping behaviors occur in response to specific stressors. Thus, between-person comparisons of coping are uninformative when participants are reporting how they cope with entirely different types of stress.

Research to date has pinpointed which specific forms of stress are most closely associated with pregnancy outcomes. That is, life events and chronic stress both contribute significantly to low birth weight whereas pregnancy anxiety is a risk factor for preterm birth (Dunkel Schetter, 2009; Dunkel Schetter & Lobel, 2012), but how women cope with each of these distinct forms of stress has not yet been studied. Future studies can address this complex issue by first using qualitative or mixed methods approaches to determine the specific stressors faced by specific subgroups of pregnant women at risk of adverse outcomes. It is difficult to capture the full story of a woman’s cognitions, emotions and behavior during pregnancy using brief inventories with closed ended items rated on Likert scales. In contrast, narrative approaches would allow women to tell their stories in a way that could develop a fuller understanding of their experiences (Stephens, 2011). For example, in a recent qualitative study of a small sample of low-income, ethnically diverse men and women, participants identified racism, finances, relationships, violence, unemployment, and substance abuse as significant sources of stress in their communities (Abdou et al., 2010). After identifying the specific sources of stress in a given study population, researchers can then ask questions about coping behaviors in the context of those stressors. Because such stressors are usually relevant only to subgroups of a population, researchers would need to screen and select participants with shared environments and experiences.

Finally, focusing on women’s pregnancy-specific coping efforts seems like the most fruitful avenue for future research. Because the evidence suggests that pregnancy-related anxiety may be particularly potent in effects on mothers and their offspring, it is important to understand the ways that women attempt to manage their anxiety, as well as the demands and strains associated with pregnancy. In the studies reviewed above, certain pregnancy-specific coping strategies (particularly avoidance and positive appraisal) were associated with a variety of less than optimal outcomes, including prenatal distress or depressive symptoms (Giurgescu et al., 2006; Hamilton & Lobel, 2008; Huizink et al., 2002a; Levy-Shiff et al., 2002; Lowenkron, 1999; Pakenham, Smith, & Rattan, 2007; Rudnicki et al., 2001; Yali & Lobel, 1999; Yali & Lobel, 2002), prenatal physical symptoms (Chang et al., 2011; Levy-Shiff et al., 2002), postpartum depression or depressive symptoms (Besser & Priel, 2003, Soliday, McCluskey-Fawcett & O’Brien 1999; Levy-Shiff et al., 1998), and infant developmental difficulties (Levy-Shiff et al., 1998; Levy-Shiff et al, 2002). Future studies could build upon these findings by exploring whether pregnancy-specific coping strategies moderate the effect of pregnancy-specific stress or anxiety on maternal and child health outcomes. For example, researchers could test the hypothesis that coping with pregnancy-specific stress through avoidance strengthens the association between stress and birth outcomes, or that positive reappraisal attenuates the relationship between pregnancy-specific stress and postpartum depression. Using measures of pregnancy-specific stress may also address concerns about the reliability of coping self-reports, because items that specifically reference pregnancy, birth, and parenting concerns should yield more accurate recall and reporting of coping efforts. For example, a pregnant woman may respond differently to a pregnancy-specific item such as “asked doctors or nurses about the birth” than to a similar but less specific item taken from general coping scales such as “talked to someone to find out more about the situation.” Thus, situation-specific measures of coping have the potential to provide a richer and more reliable portrait of how women cope during pregnancy.

Pregnancy-Specific Considerations

Although the broader field of stress and coping research provides many insights that can inform the study of these processes in maternal and child health, it is also critical to recognize that pregnancy is a unique health experience. Unlike other health and illness contexts studied by health psychologists such as cancer or heart disease, pregnancy is not an illness and is commonly associated with positive psychological experiences. Yet, many women may be coping with an unintended pregnancy, bothersome physical symptoms, medical risk conditions or other chronic life strains. Pregnancy, which typically spans 40 weeks, is also time-limited in nature. The finite nature may influence how women appraise and cope with at least some pregnancy-specific stressors.

By its very nature, pregnancy is also embedded within a broader interpersonal context and therefore, it is particularly important to understand the influence of an expecting mother’s close personal relationships on her coping effectiveness. A recent study by Tanner Stapleton and collegues (2012) examined the maternal relationship with a baby’s father in detail and found that paternal support during pregnancy predicted maternal prepartum and postpartum distress, as did the quality of their relationship. This suggests that a woman’s coping skills regarding soliciting family support especially from partners may be one area in which to focus attention. Models of dyadic coping developed in other populations suggest that a partner’s ways of coping with stress affects the other partner’s coping methods, as well as the effectiveness of his or her coping (DeLongis, Capreol, Holtzman, O’Brien, & Campbell, 2004; O’Brien, DeLongis, Pomaki, Puterman, & Zwicker, 2009). Studying the coping of fathers or partners, as well as mothers, could be an important contribution to our understanding of stress and coping during pregnancy.

Implications for Interventions

The descriptive studies on coping during pregnancy reviewed here have often been carried out with the intention of informing interventions efforts to help pregnant women who are experiencing high levels of stress. By gaining an understanding of how coping differs between women who experience adverse outcomes and those who do not, this body of research aims to identify optimal ways for women to avoid the negative effects of stressful experiences. After reviewing this literature, however, we concluded that the evidence-base is insufficient to inform the development of prenatal stress management or coping enhancement interventions. For example, there are no theory-derived, empirically-based predictive models to guide such intervention plans although experts recommend having one (West & Aiken, 1997). Evidence in studies we reviewed suggests that approach-oriented forms of coping may be more adaptive than avoidant responses, yet some pregnant women may be facing chronic and too often intractable environmental stressors requiring acceptance whereas others are experiencing more controllable demands with greater resources. Because the ways that women cope with pregnancy stress are shaped by a broad range of influences including personality traits and resources, interpersonal relationships, culture, and the nature of stressful conditions, trying to change the ways that women respond to stress may be challenging, not always beneficial, and arguably even be harmful in some cases Therefore, we believe that it is imperative to gain a better understanding of the various specific types of stressors that specific at-risk subgroups of women encounter during pregnancy (e.g. being low SES, experiencing racial or sexual discrimination), and to develop predictive models of stress and coping for pregnancy-specific contexts, and then tailor interventions to meet the needs of these subgroups.

Conclusion

Does coping help pregnant women to manage the negative effects of stress? Undoubtedly it does, but research has yet to show us how (Dole et al., 2004; Levy-Shiff et al., 1998; Levy-Shiff et al, 2002). Firm evidence of mediational mechanisms and for relevant moderating factors should be established before implementing interventions that are based on teaching women how to better cope during pregnancy. Looking ahead, researchers should develop a greater understanding of the particular challenges that women face and must cope with during pregnancy and across the lifespan, use strong and consistent instrumentation, and conduct longitudinal studies in large samples. A more rigorous approach to the study of coping during pregnancy could provide evidence needed to develop empirically-based interventions targeting modifiable risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Supplementary Material

References

- Abdou CM, Dunkel Schetter C, Roubinov D, Jones F, Tsai S, Jones L, Hobel C. Community perspectives: Mixed-methods investigation of resilience, stress and health. Ethnicity and Disease. 2010;20(S2):41–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderdice F, Lynn F, Lobel M. A review and psychometric evaluation of pregnancy-specific stress measures. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012;33(2):62–77. doi: 10.3109/0167482X.2012.673040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Social Science & Medicine. 1993;36(6):725–733. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcazar H, Krull JL, Peterson G. Acculturation and family functioning are related to health risks among pregnant Mexican American women. Behavioral Medicine. 2001;27(2):62–70. doi: 10.1080/08964280109595772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcazar H, Peterson GW, Krull JL. Acculturation and family cohesiveness in Mexican American pregnant women: Social and health implications. Family & Community Health. 1997;20(3):16–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N. Manual for the Bayley Scales of Infant Development. 2. New York: The Psychological Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bergner A, Beyer R, Klapp BF, Rauchfuss M. Pregnancy after early pregnancy loss: A prospective study of anxiety, depressive symptomatology and coping. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2008;29(2):105–113. doi: 10.1080/01674820701687521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besser A, Priel B. Trait vulnerability and coping strategies in the transition to motherhood. Current Psychology. 2003;22(1):57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Blake SM, Murray KD, El-Khorazaty MN, Gantz MG, Kiely M, Best D, El-Mohandes AA. Environmental tobacco smoke avoidance among pregnant African-American nonsmokers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;36(3):225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blechman EA, Lowell ES, Garrett J. Prosocial coping and substance use during pregnancy. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24(1):99–109. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borcherding KE. Coping in healthy primigravidae pregnant women. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecological, and Neonatal Nursing. 2009;38(4):453–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borders AEB, Grobman WA, Amsden LB, Holl JL. Chronic stress and low birth weight neonates in a low-income population of women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;109(2):331–338. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000250535.97920.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisch KH, Munz D, Bemmerer-Mayer K, Terinde R, Kreienberg R, Kachele H. Coping styles of pregnant women after prenatal ultrasound screening for fetal malformation. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2003;55(2):91–97. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00572-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson JW, Keefe FJ, Affleck G, Rumble ME, Caldwell DS, Beaupre PM, Weisberg JN. A comparison of conventional pain coping skills training and pain coping skills training with a maintenance training component: A daily diary analysis of short-and long-term treatment effects. The Journal of Pain. 2006;7(9):615–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;4(1):92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. Stress, coping, and health. In: Friedman HS, Silver RC, editors. Foundations of Health Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 117–44. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. Coping. In: Contrada R, Baum A, editors. Handbook of Stress Science: Biology, Psychology, and Health. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56(2):267–283. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challis J, Sloboda D, Matthews S, Holloway A, Alfaidy N, Howe D, Newnham J. Fetal hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal (HPA) development and activation as a determinant of the timing of birth, and of postnatal disease. Endocrine Research. 2000;26(4):489–504. doi: 10.3109/07435800009048560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HY, Yang YL, Jensen MP, Lee CN, Lai YH. The experience of and coping with lumbopelvic pain among pregnant women in Taiwan. Pain Medicine. 2011;12(6):846–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Holzman C, Chung H, Senagore P, Talge NM, Siler-Khodr T. Levels of maternal serum corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) at midpregnancy in relation to maternal characteristics. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(6):820–832. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Neilands TB, Chambers DB, Taylor JM, Folkman S. A validity and reliability study of the coping self-efficacy scale. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2006;11(3):421–437. doi: 10.1348/135910705X53155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements AD, Ermakova AV. Surrender to God and stress: A possible link between religiosity and health. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2012;4(2):93–107. [Google Scholar]

- Conner TS, Tennen H, Zautra AJ, Affleck G, Armeli S, Fifield J. Coping with rheumatoid arthritis pain in daily life: Within-person analyses reveal hidden vulnerability for the formerly depressed. Pain. 2006;126(1–3):198–209. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote-Arsenault D. Threat appraisal, coping, and emotions across pregnancy subsequent to perinatal loss. Nursing Research. 2007;56(2):108–116. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000263970.08878.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi M, Larson R. Validity and reliability of the Experience-Sampling Method. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1987;175(9):526–536. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198709000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa D, Dritsa M, Larouche J, Brender W. Psychosocial predictors of labor/delivery complications and infant birth weight: A prospective multivariate study. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2000;21(3):137–148. doi: 10.3109/01674820009075621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa D, Larouche J, Dritsa M, Brender W. Psychosocial correlates of prepartum and postpartum depressed mood. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2000;59(1):31–40. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Tychey C, Spitz E, Briancon S, Lighezzolo J, Girvan F, Rosati A, Vincent S. Pre-and postnatal depression and coping: A comparative approach. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;85(3):323–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLongis A, Capreol M, Holtzman S, O’Brien T, Campbell J. Social support and social strain among husbands and wives: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(3):470–479. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere K, Lenaerts H, Nijs P, Vanassche FA. Individual coping style and psychological attitudes during pregnancy predict depression levels during pregnancy and during postpartum. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1995;91(2):95–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1995.tb09747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere K, Maes A, Nijs P, Odendael H, Vanassche FA. Coping style and preterm labor. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;16(2):109–115. doi: 10.3109/01674829509042786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPietro JA, Hawkins M, Hilton SC, Costigan KA, Pressman EK. Maternal stress and affect influence fetal neurobehavioral development. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(5):659–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dole N, Savitz DA, Hertz-Picciotto I, Siega-Riz AM, McMahon MJ, Buekens P. Maternal stress and preterm birth. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;157(1):14–24. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dole N, Savitz DA, Siega-Riz AM, Hertz-Picciotto I, McMahon MJ, Buelkens P. Psychosocial factors and preterm birth among African American and white women in central North Carolina. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(8):1358–1365. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.8.1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkel Schetter C. Stress processes in pregnancy and preterm birth. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18(4):205–209. [Google Scholar]

- Dunkel Schetter C. Psychological science on pregnancy: Stress processes, biopsychosocial models, and emerging research issues. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62(1):531–558. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.031809.130727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkel Schetter C, Dolbier C. Resilience in the context of chronic stress and health in adults. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2011;5(9):634–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00379.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkel Schetter C, Glynn LM. Handbook of Stress. New York: Springer; 2010. Stress in Pregnancy: Empirical Evidence and Theoretical Issues to Guide Interdisciplinary Research. In R. Contrada & A. Baum (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Dunkel Schetter C, Lobel M. Pregnancy and birth: A multilevel analysis of stress and birth weight. In: Revenson TA, Baum A, Singer J, editors. Handbook of Health Psychology. 2. London: Psychol. Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dunkel-Schetter C, Feinstein LG, Taylor SE, Falke RL. Patterns of coping with cancer. Health Psychology. 1992;11(2):79. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.2.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endler N, Parker J. Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS): Manual. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Entringer S, Buss C, Andersen J, Chicz-DeMet A, Wadhwa P. Ecological momentary assessment of maternal cortisol profiles over a multiple-day period predicts the length of human gestation. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2011;73(6):469–474. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31821fbf9a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faisal-Cury A, Savoia MG, Menezes PR. Coping style and depressive symptomatology during pregnancy in a private setting sample. The Spanish Journal of Psychology. 2012;15(1):295–305. doi: 10.5209/rev_sjop.2012.v15.n1.37336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang CY, Dunkel-Schetter C, Tatsugawa ZH, Fox MA, Bass HN, Crandall BF, Grody WW. Attitudes toward genetic carrier screening for cystic fibrosis among pregnant women: The role of health beliefs and avoidant coping style. Women’s Health. 1997;3(1):31–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Manual for the Ways of Coping Questionnaire. Palo Alto, CA: Mind Garden Inc. for Consulting Psychologists Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:745–774. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford E, Ayers S, Bradley R. Exploration of a cognitive model to predict post-traumatic stress symptoms following childbirth. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2010;24(3):353–359. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesbrecht G, Campbell T, Letourneau N, Kooistra L, Kaplan B. Psychological distress and salivary cortisol covary within persons during pregnancy. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(2):270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giurgescu C, Penckofer S, Maurer MC, Bryant FB. Impact of uncertainty, social support, and prenatal coping on the psychological well-being of high-risk pregnant women. Nursing Research. 2006;55(5):356–365. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200609000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn LM, Wadhwa PD, Dunkel-Schetter C, Chicz-DeMet A, Sandman CA. When stress happens matters: Effects of earthquake timing on stress responsivity in pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;184(4):637–642. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.111066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Whiffen VE, Wallace PM, Mount JH. Prospective investigation of postpartum depression: Factors involved in onset and recovery. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100(2):122–132. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JG, Lobel M. Types, patterns, and predictors of coping with stress during pregnancy: Examination of the Revised Prenatal Coping Inventory in a diverse sample. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;29(2):97–104. doi: 10.1080/01674820701690624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harville EW, Savitz DA, Dole N, Herring AH, Thorp JM. Stress questionnaires and stress biomarkers during pregnancy. Journal of Women’s Health. 2009;18(9):1425–1433. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harville EW, Savitz DA, Dole N, Thorp JM, Jr, Herring AH. Psychological and biological markers of stress and bacterial vaginosis in pregnant women. BJOG. 2007;114(2):216–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard M, Henriksen TB, Secher NJ, Hatch MC, Sabroe S. Do stressful life events affect duration of gestation and risk of preterm delivery? Epidemiology. 1996;7(4):339–345. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199607000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim E, Augustiny K, Blaser A, Schaffner L. Manual zur Erfassung der Krankheitsbewältigung: Die Berner Bewältigungsformen (BEFO) Huber: Bern; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. The Ecology of Stress. Washington, D.C: Hemisphere; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist. 1989;44(3):513–524. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honey KL, Bennett P, Morgan M. Predicting postnatal depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2003;76(1–3):201–210. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honey KL, Morgan M, Bennett P. A stress-coping transactional model of low mood following childbirth. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2003;21(2):129–143. [Google Scholar]

- Huizink AC, Robles de Medina PG, Mulder EJ, Visser GH, Buitelaar JK. Coping in normal pregnancy. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2002a;24(2):132–140. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2402_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizink AC, Robles de Medina PG, Mulder EJ, Visser GH, Buitelaar JK. Psychological measures of prental stress as predictors of infant termperamanet. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002b;41(9):1078–1085. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200209000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James SA, Hartnett SA, Kalsbeek WD. John Henryism and blood pressure differences among black men. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1983;6(3):259–278. doi: 10.1007/BF01315113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MP, Keefe FJ, Lefebvre JC, Romano JM, Turner JA. One- and two-item measures of pain beliefs and coping strategies. Pain. 2003;104:453–69. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MS, Lydon J, Séguin L, Goulet L, Kahn SR, McNamara H, Sharma S. Stress pathways to spontaneous preterm birth: The role of stressors, psychological distress, and stress hormones. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;169(11):1319–1326. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latendresse G, Ruiz RJ. Maternal coping style and perceived adequacy of income predict CRH levels at 14–20 weeks of gestation. Biological Research for Nursing. 2010;12(2):125–136. doi: 10.1177/1099800410377111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lederman S, Rauh V, Weiss L, Stein J, Hoepner L, Becker M, Perera F. The effects of the World Trade Center event on birth outcomes among term deliveries at three lower Manhattan hospitals. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2004;112(17):1772–1178. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leithner K, Maar A, Maritsch F. Experiences with a psychological help service for women following a prenatal diagnosis: Results of a follow-up study. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;23(3):183–192. doi: 10.3109/01674820209074671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Shiff R, Dimitrovsky L, Shulman S, Har-Even D. Cognitive appraisals, coping strategies, and support resources as correlates of parenting and infant development. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34(6):1417–1427. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Shiff R, Lerman M, Har-Even D, Hod M. Maternal adjustment and infant outcome in medically defined high-risk pregnancy. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(1):93–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Shafer D, Napolitano C. Momentary mood and coping processes in TMD pain. Health Psychology. 2004;23(4):354–362. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobel M. Pregnancy and mental health. In: Friedman H, editor. Encyclopedia of mental health. Vol. 3. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Lobel M, Cannella D, Graham J, DeVincent C, Schneider J, Meyer B. Pregnancy-specific stress, prenatal health behaviors, and birth outcomes. Health Psychology. 2008;27(5):604–615. doi: 10.1037/a0013242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobel M, Hamilton JG, Cannella DT. Psychosocial perspectives on pregnancy: Prenatal maternal stress and coping. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2008;2(4):1600–1623. [Google Scholar]

- Lobel M, Yali AM, Zhu W, DeVincent C, Meyer B. Beneficial associations between optimistic disposition and emotional distress in high-risk pregnancy. Psychology & Health. 2002;17(1):77–96. [Google Scholar]