Abstract

Purpose

HIV protease inhibitors are associated with HIV protease inhibitor–related lipodystrophy syndrome. We hypothesized that liposarcomas would be similarly susceptible to the apoptotic effects of an HIV protease inhibitor, nelfinavir.

Methods

We conducted a phase I trial of nelfinavir for liposarcomas. There was no limit to prior chemotherapy. The starting dose was 1,250 mg twice daily (Level 1). Doses were escalated in cohorts of three to a maximally evaluated dose of 4,250 mg (Level 5). One cycle was 28 days. Steady-state pharmacokinetics (PKs) for nelfinavir and its primary active metabolite, M8, were determined at Levels 4 (3,000 mg) and 5.

Results

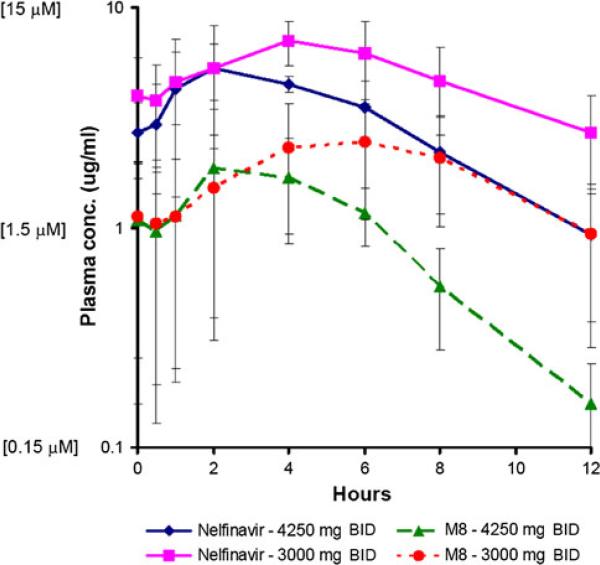

Twenty subjects (13 males) were enrolled. Median (range) age was 64 years (37–81). One subject at Level 1 experienced reversible, grade 3 pancreatitis after 1 week and was replaced. No other dose-limiting toxicities were observed. Median (range) number of cycles was 3 (0.6–13.5). Overall best responses observed were 1 partial response, 1 minor response, 4 stable disease, and 13 progressive disease. Mean peak plasma levels and AUCs for nelfinavir were higher at Level 4 (7.3 mg/L; 60.9 mg/L × h) than 5 (6.3 mg/L; 37.7 mg/L × h). The mean ratio of M8:nelfinavir AUCs for both levels was ~1:3.

Conclusions

PKs demonstrate auto-induction of nelfinavir clearance at the doses studied, although the mechanism remains unclear. Peak plasma concentrations were within range where anticancer activity was demonstrated in vitro. M8 metabolite is present at ~1/3 the level of nelfinavir and may also contribute to the anticancer activity observed.

Keywords: Nelfinavir, Phase I, Liposarcoma, Pharmacokinetics

Introduction

Liposarcomas are the most common adult soft-tissue sarcoma. Despite its common preadipocyte or adipocyte origin, its principal subtypes (well-differentiated/dedifferentiated, myxoid/round cell, and pleomorphic) represent distinct diseases with different morphology, genetics, and natural history [1]. Surgery and radiation remain the principle treatments for localized tumors. Outcomes for recurrent or metastatic liposarcoma are poor because of their relative insensitivity to chemotherapy.

HIV protease inhibitors (PIs) prevent cleavage of gag and gag-pol protein precursors in HIV-infected cells; this inhibition of cleavage prevents HIV maturation and thereby blocks the infectivity of nascent virions [2]. HIV PI use is linked to a clinical syndrome of peripheral lipoatrophy and central fat accumulation associated with insulin resistance and hyperlipidemia, known as “HIV protease inhibitor-related lipodystrophy syndrome” [3]. Complicating its characterization and incidence, lipoatrophy has also been linked to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) use [4]. NRTI-related lipoatrophy has been proposed to result from NRTI-induced damage to mitochondrial DNA [5]. In contrast, inhibition of adipocyte differentiation via inhibition of PPARγ initially was theorized to underlie the pathobiology of “HIV PI-related lipodystrophy syndrome,” based upon the observation that the HIV PIs indinavir and ritonavir reduce peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) levels during preadipocyte differentiation [6, 7]. More recently, alteration of sterol regulatory element–binding protein-1 (SREBP-1) expression has been advanced as the basis of this pathology [8]. SREBP-1 is a basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper transcription factor that promotes lipogenic gene expression and adipogenesis [9]. Both gene and protein expression of major adipocyte differentiation markers and cytokines in subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue from HIV-1 infected subjects who developed peripheral lipoatrophy while on HIV PIs was compared with seronegative healthy controls [8]. Interestingly, SREBP-1 gene expression was decreased by a median of 93 %, whereas SREBP-1 protein concentration was increased 2.6-fold.

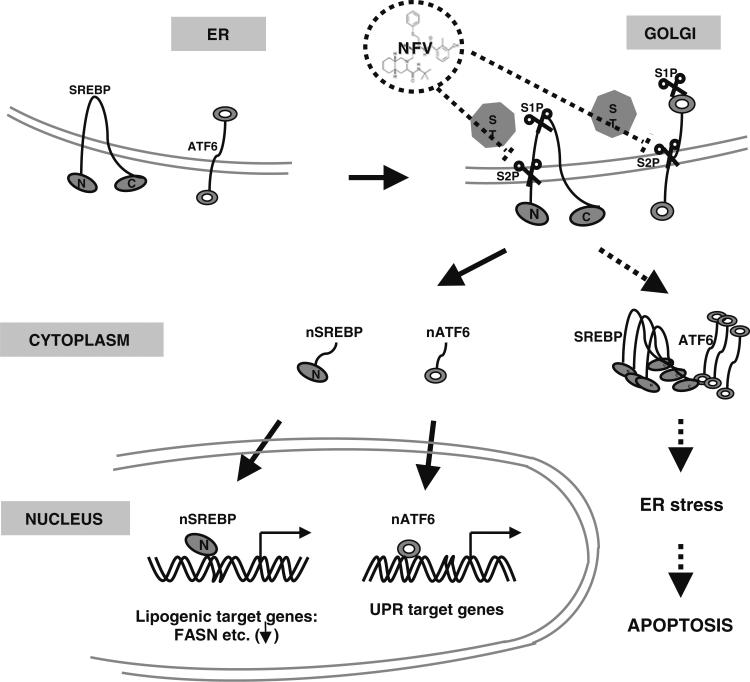

There are three SREBP isoforms: SREBP-2, SREBP-1a, and SREBP-1c; the latter two are alternative splice products of a single gene [9]. SREBP-1c is the primary isoform in adipose tissue, but is also present in liver, adrenal gland, ovary, kidney, and prostate [10, 11]. SREBPs are produced as inactive precursors bound to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) by a hydrophobic tail by SREBP cleavage–activating protein (SCAP) [12]. In the presence of cholesterol, SCAP functions as a sterol-sensing domain and binds insulin-induced gene-1 or gene-2 (Insig-1 or -2) to the ER [13]. Insigs block the proteolytic processing of SREBP required for its activation [13]. Upon cholesterol depletion, SCAP and Insig fail to interact, and the SREBP-SCAP complex is transported to the golgi apparatus, where it is processed in two sequential cleavage steps by site-1 protease (S1P) and site-2 protease (S2P) to release the transcriptionally active NH2 terminus of SREBP into the nucleus. There it binds the promoters of target genes as dimers in a process known as “regulated intramembrane proteolysis (RIP)” (Fig. 1), [14, 15].

Fig. 1.

Current model of nelfinavir in liposarcoma. SREBP and ATF6 are synthesized as ER transmembrane proteins and transported to the Golgi upon appropriate stimulus. Luminal S1P cleaves first, followed by intramembrane S2P to liberate the transcriptionally active amino-terminal segments of nSREBP and nATF6 from the Golgi membrane to migrate to the nucleus to active transcription of lipogenic target genes such as FASN or UPR target genes (solid arrow); NFV inhibits liposarcoma proliferation and promotes apoptosis through inhibition of RIP processing of SREBP and ATF6. Inhibition of S2P cleavage by NFV leads to retention of precursor SREBP and ATF6 proteins in the ER or Golgi and block of transcriptional activation of target genes (FASN). Accumulation of unprocessed SREBP and ATF6 induces ER stress, which leads to caspase-dependent apoptosis (dotted arrow). NFV, nelfinavir; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; nSREBP-1, nuclear active SREBP; nATF6, nuclear active ATF6; FASN, fatty acid synthase; UPR, unfolded protein response; S1P, site-1 protease; S2P, site-2 protease; RIP, regulated intramembrane proteolysis (Adapted from Guan et al. [15])

Based upon their adipocytic origin and their basal expression of SREBP-1c, we hypothesized that liposarcoma would be a good model to test our hypothesis that HIV PIs are active anticancer agents. We previously demonstrated that the most potent HIV PI identified in clonogenic assays, nelfinavir (Viracept®, Pfizer), led to a dose-dependent increase in precursor SREBP-1 protein expression in the absence of increased gene expression [16]. This observation is strikingly similar to the results observed in HIV-infected individuals on HIV PIs [8]. Additionally, increased SREBP-1 expression mediated inhibition of proliferation through p21-mediated G1 cell cycle block and induction of Fas- and Bax-dependent apoptosis [16]. Consequently, we developed the present phase 1/2 trial of nelfinavir in recurrent, non-surgically amenable liposarcomas. We report here the results of the phase 1 portion of this study.

Materials and methods

Subject eligibility

Subjects were required to have histologically confirmed liposarcoma of any subtype, which was recurrent, metastatic, or unresectable. Subjects must have been ≥18 years and possessed an ECOG performance status 0–2. Women of child-bearing potential and men must have agreed to use adequate contraception prior to study entry as the effects of nelfinavir on the developing human fetus was unknown. There was no limit to prior chemotherapy, and prior radiation was allowed; however, all prior therapy must have been completed >3 weeks prior to enrollment. All subjects must have had measurable disease. Organ function requirements included an absolute neutrophil count ≥1,000/μL, platelet count ≥75,000/μL, bilirubin ≤2.0 g/dL, and alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase ≤2.0 times the upper limit of normal.

Subjects were excluded for prior or current use of an HIV PI, concurrent use of other investigational agents, strong inhibitors of CYP3A4 including grapefruit juice, St. John's Wort, and enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants. Additionally, subjects with uncontrolled intercurrent illness or subjects who had not recovered from toxicities associated with previous chemotherapy or radiation therapy were excluded.

This trial was conducted under a food and drug administration (FDA) Investigational New Drug Application (IND 70,194) held by the City of Hope (COH). This trial was approved by the COH Institutional Review Board. All subjects received and signed an informed consent document.

Trial design

This was a single-institution, phase I trial to determine the toxicities and maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of nelfinavir in subjects with liposarcoma. An additional objective was to evaluate the pharmacokinetics of nelfinavir. The objectives of the phase II portion of this trial were to assess the response rate and progression-free survival of subjects treated with nelfinavir and to evaluate expression of proteins in surrogate abdominal adipose tissue identified in preclinical studies to be necessary for nelfinavir cytotoxicity. The phase II results will not be reported here.

Nelfinavir was administered orally, twice daily with a meal or light snack at the assigned dose level. One cycle was defined as 28 days. A drug diary was maintained by the subject and reviewed after each cycle. Monitoring for treatment-related toxicity included history, physical examination, and performance status prior to each cycle; serum chemistries, complete blood counts, and lipid panel were performed prior to week 3 of the first cycle and prior to each cycle.

Pharmacokinetic analyses were performed in subjects treated at dose Levels 4 and 5 (3,000 and 4,500 mg twice daily, respectively). Serial blood samples were collected on day 8 of the first cycle at the following times: predose (within 15 min before the morning dose) and at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h after the morning dose. For each sample, approximately 4 mL blood was collected in a Vacutainer® tube containing EDTA (purple top). Blood samples were kept on ice and centrifuged within 1 h of collection (1,000×g, 15 min). Plasma was transferred to appropriately labeled polypropylene tubes and stored at –20 °C or lower until subsequent analysis.

Analysis of plasma concentrations of nelfinavir and its active metabolite (M8) along with ritonavir levels was performed using a validated LC–MS/MS in the COH Analytical Pharmacology Core, as previously described [15]. Briefly, nelfinavir, M8, and internal standard (reserpine) were extracted from human plasma by protein precipitation and organic extraction. After evaporation of the organic phase under nitrogen, the residue was reconstituted in mobile phase and analyzed. Quantification was done using multiple reaction monitoring, in positive ionmode, on a Waters Quattro Premier XE triple quadrupole tandem mass spectrometer. The assay had a lower limit of quantitation of 1 nM nelfinavir and M8 from a starting volume of 200 μL of plasma. The inter- and intraday precision and accuracy of the method were within ±10 % across the range of the standard curve.

Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated from plasma concentration–time data for nelfinavir and M8 using standard non-compartmental analyses. Maximum observed plasma concentrations (Cmax) and the time to reach maximum plasma concentrations (Tmax) for nelfinavir and M8 were determined from the concentration–time data. Area under the plasma concentration–time curve over the dosing interval (AUC0–) and extrapolated to infinity (AUC0–∞) was estimated using the linear/log trapezoidal approximation. Finally, the ratio of metabolite to parent (M/P; i.e., M8/nelfinavir) was determined based on the AUC values.

A modified 3 + 3 Fibonacci phase 1 dose escalation schema was employed [17]. The initial dose level (Level 1) was the FDA-approved dose for HIV infection (1,250 mg twice daily). Subsequent levels evaluated were the following: Level 2, 1,500 mg; Level 3, 2,125 mg; Level 4, 3,000 mg; Level 5, 4,250 mg.

Tumor burden was measured radiographically using response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST) prior to treatment and after every third treatment cycle [18]. Toxicity was graded according to the NCI common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE), version 3.0. To be evaluable for toxicity, a subject must have completed at least one cycle of treatment or experienced a dose-limiting toxicity (DLT). DLT was defined as any grade 3 toxicity not reversible to ≤ grade 2 within 1 week, or any grade 4 toxicity. Hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia, diarrhea, and nausea/vomiting were not included as DLTs unless they were grades 3 or 4 uncontrolled with maximal medicinal therapy (atorvastatin and gemfibrozil for hyperlipidemia and up to 3 oral hypoglycemics for hyperglycemia). All subjects not evaluable for toxicity were replaced. The MTD was defined as the highest dose at which <33 % of subjects experienced DLT at least possibly attributable to nelfinavir, when at least six subjects were treated at that dose level. Intrasubject dose escalation by one dose level was permissible if no grade 2 or higher toxicity was observed after at least one cycle.

Results

Subject characteristics

From August 10, 2006, to June 18, 2009, 20 subjects were enrolled. The characteristics of the subjects are listed in Table 1. All subjects were eligible; however, 1 subject at dose Level 1 developed grade 3 pancreatitis after 2 weeks of treatment requiring hospitalization, which reversed within 3 days. Acute pancreatitis is a rare, known toxicity described for nelfinavir [19]. This subject was replaced because one cycle of treatment was not completed, and the prespecified DLT was not reached (grade 3 toxicity not reversible to ≤ grade 2 within 1 week).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics for subjects receiving Nelfinavir for liposarcoma

| Characteristic | No. of subjects (N = 20) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 62 | |

| Range | 45–81 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 13 | 65 |

| Female | 7 | 35 |

| Histology | ||

| Well-differentiated liposarcoma/atypical lipomatous tumor | 7 | 35 |

| Dedifferentiated liposarcoma | 10 | 50 |

| Myxoid | 2 | 10 |

| Pleomorphic | 1 | 5 |

Toxicity

No other dose-limiting toxicities, grade 3 or 4, were observed at any of the dose levels tested. Hematologic toxicities were predominantly grade 1, with only one subject experiencing grade 2 anemia and lymphopenia during the first cycle. In subsequent courses, there were 2 subjects with grade 2 anemia and 1 with grade 2 decrease in neutrophils. 11 subjects experienced grade 1 or 2 diarrhea during the first course, and 7 subjects encountered grade 1 diarrhea in subsequent courses. Observed liver toxicities were grade 1 for all dose levels, except for one subject with grade 2 alkaline phosphatase elevation and one grade 2 AST increase (Table 2).

Table 2.

Acute toxicity

| System | Course 1 |

Subsequent courses |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | |

| Blood/bone marrow | ||||||||

| Hemoglobin | 3 | 1 | – | – | 2 | 2 | – | – |

| Leukocytes (total WBC) | 2 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – |

| Lymphopenia | – | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – | – |

| Neutrophils | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – |

| Platelets | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – |

| Other | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cardiac arrhythmia ventricular arrhythmia | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Constitutional | ||||||||

| Fatigue | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | – |

| Weight loss | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – |

| Dermatology/skin | ||||||||

| Rash/desquamation | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – |

| Other | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||||||

| Anorexia | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – |

| Diarrhea | 9 | 2 | – | – | 7 | – | – | – |

| Nausea | 2 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – |

| Vomiting | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – |

| Hemorrhage/bleeding | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hepatobiliary/pancreatitis | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lymphatics/limb edema | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Laboratory | ||||||||

| ALT, SGPT | 3 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – |

| AST, SGOT | 3 | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | – | – |

| Album, serum-low | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 2 | 1 | – | – | 2 | – | – | – |

| Bicarbonate, serum-low | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cholesterol, serum-high | 2 | – | – | – | 3 | 1 | – | – |

| Glucose, serum-high | 1 | 1 | – | – | 3 | – | – | – |

| Lipase | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Potassium, serum-low | 2 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – |

| Triglyceride, serum-high | 2 | – | – | – | 2 | – | – | – |

| Neurology dizziness | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pain | – | 2 | – | – | 2 | – | – | – |

| Pulmonary dyspnea | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – |

| Hypoxia | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – |

| Other | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – |

MTD was not reached at dose Level 5, because at this dose level, PK data demonstrated auto-induction of nelfinavir clearance. Subjects at higher dose levels did not experience more severe hematologic or gastrointestinal toxicities (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Pharmacokinetic data for nelfinavir and active metabolite M8. Pharmacokinetic results of dosing nelfinavir 3000 and 4250 mg BID demonstrate higher mean peak nelfinavir and M8 concentrations and corresponding AUC values. BID, twice daily (Elsevier, license# 2982560891165)

Results

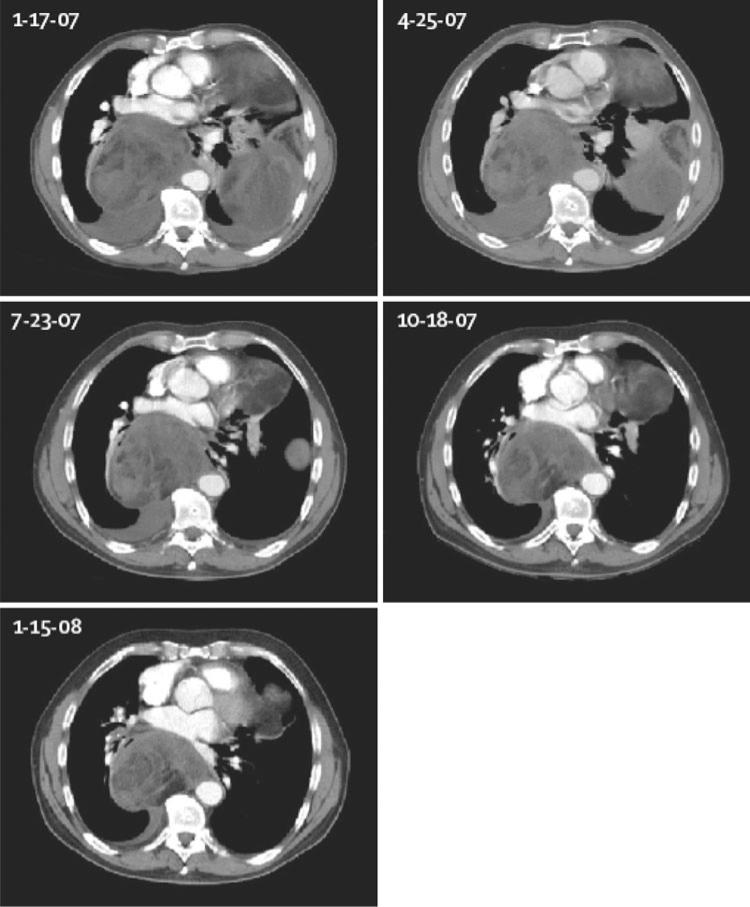

Table 3 lists the responses in the 20 patients who completed therapy. Using RECIST criteria, CT partial response (PR) was observed in 1 subject, 1 subject demonstrated reduction in tumor size, but less than a PR, and stable disease (SD) was observed in 4 other subjects. A total of 13 subjects developed progressive disease at initial evaluation, and 1 was not evaluable secondary to grade 3 pancreatitis during cycle 1. Average length of treatment ranged from 0.6 to 13.5 months (median 3 months). Notably, the subject who achieved a PR, a 63-year-old male with dedifferentiated liposarcoma, received treatment for a total of 13.5 months (Fig. 3). He was taken off study due to development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with 11q23 (MLL), which was consistent with development of secondary AML related to his prior significant exposure to anthracycline and alkylator chemotherapies for therapy of his liposarcoma.

Table 3.

Subject response to Nelfinavir

| Subject | Age | Dx | Dose level | Best response | Duration of therapy (mos.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 81 | ALT | 1250 mg BID | SD | 5.5 |

| 2 | 61 | ALT | SD | 6.0 | |

| 3 | 72 | Dediff | Not evaluable | ||

| 4 | 37 | ALT | SD | 2.8 | |

| 5 | 63 | Dediff | 1500 mg BID | PR | 13.5 |

| 6 | 45 | Myxoid | PD | 2.4 | |

| 7 | 70 | Dediff | PD | 2.1 | |

| 8 | 66 | Dediff | 2125 mg BID | PD | 0.6 |

| 9 | 54 | Dediff | PD | 1.9 | |

| 10 | 67 | Myxoid | PD | 1.7 | |

| 11 | 42 | Pleomorphic | 3000 mg BID | PD | 1.0 |

| 12 | 62 | ALT | SD | 5.9 | |

| 13 | 69 | ALT | MR | 5.8 | |

| 14 | 66 | Dediff | 4250 mg BID | PD | 2.9 |

| 15 | 81 | ALT | PD | 3.1 | |

| 16 | 64 | ALT | PD | 4.0 | |

| 17 | 62 | Dediff | PD | 3.1 | |

| 18 | 62 | Dediff | 3000 mg BID | PD | 3.0 |

| 19 | 45 | Dediff | PD | 2.0 | |

| 20 | 64 | Dediff | PD | 1.5 |

ALT atypical lipomatous tumor, dediff dedifferentiated lip osarcoma, BID twice daily, SD stable disease, PR partial response, MR minor response, PD progressive disease

Fig. 3.

Serial chest CT scans of a patient in a clinical trial of nelfinavir for liposarcoma: Partial remission was documented in a 64-year-old male with a dedifferentiated liposarcoma unresponsive to combination chemotherapy treated with nelfinavir 1500 mg orally twice daily beginning February 8, 2007 (Adapted from Chow et al. [32])

Pharmacokinetics

The starting dose of nelfinavir was 1,250 mg twice daily (Level 1). The maximal dose evaluated was 4,250 mg twice daily (Level 5). Steady-state pharmacokinetics for nelfinavir and its primary active metabolite, M8, were determined at Levels 4 (3,000 mg twice daily) and 5. PK data are available from six subjects at dose Level 4 and three at dose Level 5 (Fig. 2). Interestingly, mean peak plasma levels and AUCs for nelfinavir were higher at the 3,000 vs. 4,250 mg BID dose levels. Because the PK data demonstrated auto-induction of nelfinavir clearance, further dose escalation past Level 5 was considered futile despite the absence of MTD toxicities observed at this dose, and further dose escalation was halted. Furthermore, time to peak plasma concentration of nelfinavir and M8 occurred later (4–6 h) with 3,000 mg vs. 2 h for the 4,250 mg dose. The mean ratio of M8:nelfinavir AUCs for both dose levels was ~1:3. Peak plasma concentrations were within the range where anticancer activity was demonstrated in vitro (5–10 μM) [15].

Nelfinavir is extensively metabolized by CYP isoenzymes CYP3A4, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP2D6. The CYP2C19 pathway generates M8, which is as pharmacologically active as the parent drug in suppressing HIV replication. Further, M8 possesses anticancer activity comparable to its parent molecule [15]. HIV (PIs) are not only substrates of CYP enzymes, but are also known to induce or inhibit some isoforms, in particular CYP3A4. The effect of nelfinavir on CYP3A4 metabolism is believed to be the result of competitive inhibition by its metabolites on CYP3A4 [20, 21]. Although the mechanism of auto-induction of nelfinavir clearance at higher dose levels is unclear, it may be due to this CYP induction, as has been observed in other protease inhibitors, such as ritonavir [22].

Discussion

The clinical syndrome of HIV protease inhibitor–induced lipodystrophy syndrome is associated with use of HIV protease inhibitors. Affected individuals develop peripheral fat wasting and central fat accumulation in association with insulin resistance and hyperlipidemia. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that HIV proteases promote apoptosis of terminally differentiated adipocytes. Nelfinavir is thought to inhibit site-2 protease (S2P), which blocks RIP processing of precursor SREBP-1 to its transcriptionally active form. Mature SREBP-1 is unable to translocate to the nucleus to transactivate lipogenic gene transcription, and liposarcoma cellular proliferation is reduced. Further, the accumulation of precursor SREBP-1 in the ER leads to significant ER stress and results in apoptosis [15]. In vivo evaluation of nelfinavir in a murine liposarcoma xenograft model led to inhibition of tumor growth without significant toxicity [15]. These clinical and preclinical observations led us to conduct a phase I trial of the HIV protease inhibitor, nelfinavir, for liposarcomas.

This trial demonstrates the feasibility of treating subjects with unresectable liposarcomas with nelfinavir. The study design was based on dosing nelfinavir in subjects infected with HIV, using a modified Fibonacci dose escalation. Overall, nelfinavir was well tolerated even at the highest dose levels, with no observed grade 3 or 4 treatment-related toxicities, except for one subject who developed reversible grade 3 pancreatitis during the first course. Most frequently occurring toxicities were grade 1 hematologic effects and diarrhea. Additionally, MTD was not reached, as auto-induction of nelfinavir metabolism was seen at dose Level 5.

Mean peak plasma levels and AUCs for nelfinavir were higher at Level 4 (7.3 mg/L; 60.9 mg/L × h) than 5 (6.3 mg/L; 37.7 mg/L × h), and the mean ratio of M8:nelfinavir AUCs for both levels was ~1:3. Therefore, pharmacokinetics demonstrate auto-induction of nelfinavir clearance at the doses evaluated. Peak plasma concentrations were within range where anticancer activity was demonstrated in vitro. Nelfinavir auto-induction may be due to its metabolism by CYP isoenzymes. More specifically, nelfinavir metabolites induce CYP3A4 at higher doses; therefore, nelfinavir induces its own metabolism. Because auto-induction was observed, further dose escalation was discontinued.

In this study, there was evidence of clinical benefit, defined as complete response, PR, plus SD. Clinical benefit was observed in 6 of 20, or 30 % of subjects. Although liposarcomas comprise varying histologies and prognoses, with the unique exception of myxoid/round cell liposarcoma, the other histologic subtypes are considered relatively chemotherapy resistant [23]. Nelfinavir was very well tolerated, even at the highest dose levels with minimal toxicities, and therefore, it warrants further testing in the phase II setting.

Nelfinavir is a promising antineoplastic agent currently being explored in a number of other ongoing clinical trials because it has also been found to downregulate the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3 K)-Akt pathway, inhibits signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) signaling, and induces malignant cell death by inducing ER stress through accumulation of misfolded proteins [24–28]. This pathway is activated in many human malignancies, and preclinical data also suggest that nelfinavir may also have radiosensitization effects. Phase I or II studies using nelfinavir in rectal, recurrent adenoid cystic head and neck, renal cell, and relapsed progressive hematologic malignancies are underway. Additionally, nelfinavir is being evaluated as an adjunct to standard chemoradiation in pancreatic, glioblastoma, cervical, and non-small-cell lung cancer [29–31].

Based upona clinical benefit in nearly one-third of subjects, and its minimal toxicity profile, we have proceeded with the planned phase II trial of nelfinavir for liposarcomas. Auto-induction was seen at dose Level 5; thus, the phase II portion on this trial is ongoing with dose Level 4 (3,000 mg BID) to evaluate for efficacy of nelfinavir in liposarcoma. Because nelfinavir was very well tolerated with minimal toxicities, future studies using it in combination with chemotherapy or radiation may be warranted.

Acknowledgments

Grant support for this trial was provided by Pfizer Inc. and the FDA Orphan Products Development Grants Program (R01FD003006).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest None.

Contributor Information

Janet Pan, Department of Medical Oncology, City of Hope, 1500 E. Duarte Rd., Duarte, CA 91010, USA.

Michelle Mott, Department of Hematology/HCT, City of Hope, Duarte, CA, USA.

Bixin Xi, Department of Molecular Pharmacology, Beckman Research Institute of City of Hope, Duarte, CA, USA.

Ernestine Hepner, Department of Hematology/HCT, City of Hope, Duarte, CA, USA.

Min Guan, Department of Molecular Pharmacology, Beckman Research Institute of City of Hope, Duarte, CA, USA.

Kristen Fousek, Department of Molecular Pharmacology, Beckman Research Institute of City of Hope, Duarte, CA, USA.

Rachel Magnusson, Department of Medical Oncology, City of Hope, 1500 E. Duarte Rd., Duarte, CA 91010, USA.

Raechelle Tinsley, Clinical Trials Office, City of Hope, Duarte, CA, USA.

Frances Valdes, Department of Medical Oncology, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA.

Paul Frankel, Department of Information Sciences, City of Hope, Duarte, CA, USA.

Timothy Synold, Department of Molecular Pharmacology, Beckman Research Institute of City of Hope, Duarte, CA, USA.

Warren A. Chow, Department of Medical Oncology, City of Hope, 1500 E. Duarte Rd., Duarte, CA 91010, USA Department of Molecular Pharmacology, Beckman Research Institute of City of Hope, Duarte, CA, USA.

References

- 1.Fletcher CDM, Rydholm A, Singer S, Sudaram M, Coindre JM. Soft tissue tumours: epidemiology, clinical features, histopathological typing and grading. In: Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, editors. Pathology & genetics: tumours of soft tissue and bone. IARC Press; Lyon: 2002. pp. 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flexner C. HIV-protease inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1281–1292. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804303381808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carr A, Samaras K, Thorisdottir A, Kaufmann GR, Chisholm DJ, Cooper DA. Diagnosis, prediction, and natural course of HIV-1 protease-inhibitor-associated lipodystrophy, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus. Lancet. 1999;353:2093–2099. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)08468-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallant JE, Staszewski S, Pozniak AL, DeJesus E, Suleiman JM, Miller MD, et al. Efficacy and safety of tenofovir DF vs stavudine in combination therapy in antiretroviral-naïve patients. JAMA. 2004;29(2):191–201. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brinkman K, Smeitink JA, Romjin JA, Reiss P. Mitochondrial toxicity induced by nucleoside-analogue reverse-transcriptase inhibitors is a key factor in the pathogenesis of antiretroviral-therapy-related lipodystrophy. Lancet. 1999;354:1112–1115. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caron M, Auclair M, Vigourox C, Glorian M, Forest C, Capeau J. The HIV protease inhibitor indinavir impairs sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 intranuclear localization, inhibits preadipocyte differentiation, and induces insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2001;50:1378–1388. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.6.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen AT, Gagnon AM, Angel JB, Sorisky A. Ritonavir increases the level of active ADD-1/SREBP-1 protein during adipogenesis. AIDS. 2000;14:2467–2473. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200011100-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bastard JP, Caron M, Vidal H, Jan V, Auclair M, Vigouroux C, et al. Association between altered expression of adipogenic factor SREBP1 in lipoatrophic adipose tissue from HIV-1-infected patients and abnormal adipocyte differentiation and insulin resistance. Lancet. 2002;359:1026–1031. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. The SREBP pathway: regulation of cholesterol metabolism by proteolysis of a membrane-bound transcription factor. Cell. 1997;89:331–340. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimomura I, Shimano H, Horton JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Differential expression of exons 1a and 1c in mRNAs for sterol regulatory element binding protein-1 in human and mouse organs and cultured cells. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:838–845. doi: 10.1172/JCI119247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ettinger SL, Sobel R, Whitmore TG, Akbari M, Bradley DR, Gleave ME, et al. Dysregulation of sterol response element-binding proteins and downstream effectors in prostate cancer during progression to androgen independence. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2212–2221. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-2148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakai J, Nohturfft A, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Cleavage of sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs) at stie-1 requires interaction with SREBP cleavage-activating protein. Evidence from in vivo competition studies. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5785–5793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang T, Espenshade PJ, Wright ME, Yabe D, Gong Y, Aebersold R, et al. Crucial step in cholesterol homeostasis: sterols promote binding of SCAP to INSIG-1, a membrane protein that facilitates retention of SREBPs in ER. Cell. 2002;110:489–500. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00872-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown MS, Ye J, Rawson RB, Goldstein JL. Regulated intramembrane proteolysis: a control mechanism conserved from bacteria to humans. Cell. 2000;100:391–398. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80675-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guan M, Fousek K, Jiang C, Guo S, Synold T, Xi B, et al. Nelfinavir induces liposarcoma apoptosis through inhibition of regulated intramembrane proteolysis of SREBP-1 and ATF6. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1796–1806. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chow WA, Guo S, Valdes-Albini F. Nelfinavir induces liposarcoma apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest by upregulating sterol regulatory element binding protein-1. Anticancer Drugs. 2006;17:891–903. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000224448.08706.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Von Hoff D, Kuhn J, Clark GM. Design and conduct of phase I trials. In: Buyse ME, Staquet MJ, Sylvester RJ, editors. Cancer clinical trials: methods and practice. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Therasse P, Arbuck S, Eisenhauser E, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European organization for research and treatment of cancer, national cancer institute of the United States, national cancer institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Martino V, Ezenfis J, Benahmou Y, Bernard B, Opolon P, Bricaire F, et al. Severe acute pancreatitis related to the use of nelfinavir in HIV infection: report of a case with positive rechallenge. AIDS. 1999;13:1421. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199907300-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lillibridge JH, Liang BH, Kerr BM, Webber S, Quart B, Shetty BV, et al. Characterisation of the selectivity and mechanism of human cytochrome P450 inhibition by the human immunodeficiency virus-protease inhibitor nelfinavir mesylate. Drug Metab Dispos. 1998;26:609–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merry C, Barry M, Ryan M, Gibbons S, Tijia J, Mulcahy F, Back D. A study of the pharmacokinetics of repetitive dosing with nelfinavir. 7th European Conference on Clinical Aspects and Treatment of HIV Infection. 1999 Abstract 831. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burton ME, Shaw LM, Schentag JJ, Evans WE. Applied pharmacokinetics & pharmacodynamics principles of therapeutic drug monitoring. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; USA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones RL, Fisher C, Al-Muderis O, Judson IR. Differential sensitivity of liposarcoma subtypes to chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2853–2860. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta AK, Lin G, Cerniglia GJ, Ahmed MS, Hahn SM, Maity A. The HIV protease inhibitor nelfinavir downregulates Akt phosphorylation by inhibiting proteasomal activity and inducing the unfolded protein response. Neoplasia. 2007;9:271–278. doi: 10.1593/neo.07124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang Z, Pore N, Cerniglia GJ, Mick R, Georgescu MM, Bernhard EJ, et al. Phosphatase and tensin homologue deficiency in glioblastoma confers resistance to radiation and temozolomide that is reversed by the protease inhibitor nelfinavir. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4467–4472. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Y, Ikezoe T, Takeuchi T, Adachi Y, Ohtsuki Y, Takeuchi S, et al. HIV-1 protease inhibitor induces growth arrest and apoptosis of human prostate cancer LNCaP cells in vitro and in vivo in conjunction with blockade of androgen receptor STAT3 and AKT signaling. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:425–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00063.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pyrko P, Kardosh A, Wang W, Xiong W, Schonthal AH, Chen TC. HIV-1 protease inhibitors nelfinavir and atazanavir induce malignant glioma death by triggering endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10920–10928. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gills JJ, Lopiccolo J, Tsurutani J, Shoemaker RH, Best CJ, Abu-Asab MS, et al. Nelfinavir, A lead HIV protease inhibitor, is a broad-spectrum, anticancer agent that induces endoplasmic reticulum stress, autophagy, and apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5183–5194. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Accessed February. 14:2012. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=nelfinavir?cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brunner TB, Geiger M, Grabenbauer GG, Lang-Welzenbach M, Mantoni TS, Cavallaro A, et al. A phase I-trial of the HIV protease inhibitor nelfinavir and chemoradiation for locally advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2699–2706. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De La Garza GO, Ismail AF, Anderson CM, Werner WW, Mihem MM, Hoffman HT, et al. Nelfinavir treatment of adenoid cystic carcinoma. A case report, Practical Radiation Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chow WA, Jiang C, Guan M. Anti-HIV drugs for cancer therapeutics: back to the future? Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:61–71. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70334-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]