Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the potential harms and ovarian cancer outcomes associated with symptom-triggered diagnostic evaluation of all women with symptoms of ovarian cancer.

Methods

Five thousand-twelve women over age 40 were prospectively enrolled in a cohort study of proactive symptom-triggered diagnostic evaluation. Women who tested positive on a Symptom Index were offered testing with CA125 and transvaginal ultrasound. Results of these tests and any subsequent procedures were recorded. Assessment of ovarian cancer outcomes for all participants through Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) was performed a year after enrollment was complete.

Results

A positive Symptom Index was found in 241 (4.8%) of participating patients and 211 (88%) participated in CA125, transvaginal ultrasound, or both CA125 and transvaginal ultrasound. Twenty surgical procedures (laparoscopy, laparotomy, vaginal) were performed in the study population (0.4% of participating women). However, only six (0.12%) were performed for a suspicious ovarian mass and only 4 (0.08%) were performed solely due to study participation. A total of eight ovarian cancers were diagnosed, 31–843days after symptom assessment (50% distant, 50% local or regional). Of the two cancers diagnosed within 6 months, one was Symptom Index-positive.

Conclusions

Proactive symptom-triggered diagnostic evaluation for ovarian cancer results in minimal unindicated surgery. A small number of ovarian cancers were identified solely on the basis of symptom-triggered diagnostic testing.

Introduction

Currently both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (the College) and the Society for Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) state that the best method to diagnose ovarian cancer is for clinicians to have a high index of suspicion in a symptomatic patient.1,2 At this time no organization endorses screening for ovarian cancer using currently available tests as screening has not been shown to reduce morbidity or mortality.1,2,3 Many mainstream media organizations encourage women to keep symptom diaries and to report symptoms to physicians; some physicians may solicit symptom reports from patients however, the safety of this practice has not been evaluated. Concerns have been raised that a focus on symptoms may result in high rates of unnecessary surgery with secondary complications. This study sought to examine the extent to which this is likely to be a problem.

Previous case control studies by our group have identified a Symptom Index algorithm which is associated with ovarian cancer (sensitivity 87.0%, specificity 87.9%).4,5,6,7,8 The Symptom Index is positive when a patient has any one of six symptoms (bloating, increased abdominal size, abdominal pain, pelvic pain, difficulty eating, feeling full quickly) occurring more than 12 times a month and present for less than a year.

Our group previously reported a pilot study of symptom-triggered screening to assess feasibility as well as patient and provider acceptability.9 The goal of our current study was to evaluate the potential harms (unnecessary surgery and testing) and ovarian cancer outcomes associated with proactively assessing symptoms with a Symptom Index followed up with routine referral for diagnostic testing.

Methods

This prospective cohort study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at the University of Washington and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. Between April 2008 and July of 2011, women attending one of the three primary care clinics at the University of Washington were approached by a research nurse to determine eligibility and interest in participating in a research trial to evaluate symptom-triggered diagnostic evaluation for ovarian cancer. The participating clinics are the three main primary care clinics for the University of Washington, serving the local community and are located in the same building as radiology, ultrasound and phlebotomy services. An initial 1,001 women were enrolled as an unscreened pilot group.10 In our initial pilot study, 80% of eligible women agreed to participate in the study.10 From September 2008 to July 2011, 5,012 women participated in Symptom Index assessment with referral for CA125 and transvaginal ultrasound when the Symptom Index was positive.

Women were eligible to participate if they were 40 years of age or older, had at least one ovary, were not pregnant, and were able to give informed consent. Those interested in participating signed an informed consent form, filled out a baseline health questionnaire and a Symptom Index assessment form. The consent form allowed for review of medical records for 12 months following participation to identify any studies or procedures performed as a result of study participation. Women then had their regularly scheduled appointment with their provider. Physicians were informed of participation in the study but were instructed not to alter their clinical management and to order any tests that the patient’s symptoms or examination warranted. At the time of the clinic visit the research nurse scored the Symptom Index as positive or negative. Those with a positive Symptom Index were offered CA125 and transvaginal ultrasound as diagnostic tests ordered as part of the study and any subsequent tests or procedures ordered by their physicians were recorded and coded as related to the study. Patients and providers were informed of the results of the study-ordered transvaginal ultrasound and CA125. Women with abnormal results on these tests were managed according to standard of care by their physicians consistent with earlier studies.9 CA125 was considered normal if less than 35 U/ml. All transvaginal ultrasounds were performed in the radiology department at the clinic by a trained sonographer and radiologist as they would be for routine clinical care. Radiologists knew patients had a positive Symptom Index and so there was special focus on the ovaries, but no specific protocol was used for scans nor was Doppler, as we wanted the intervention to mimic standard of care. Transvaginal ultrasound was considered normal if uterus, adnexa and ovaries were normal with no ascites or other abnormalities. This conservative definition of normal meant that transvaginal ultrasounds were considered abnormal even if problems were identified on scan that were clearly not ovarian, and these ultrasound findings led to appropriate treatment for non-ovarian conditions that were causing symptoms.

Approximately a year (June 2012) after study completion, all participant names (positive and negative SI) were linked to the Western Washington Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database to assess if any of the participants developed ovarian cancer, as had been done in our pilot study9. Sufficient time was allowed to be certain that all ovarian cancer cases were captured. Use of the SEER database assured us access to a comprehensive listing of cancer patients, thus providing data on women who were diagnosed with cancer after completing a Symptom Index, including women who received a negative result and did not have further interactions with study staff.

STATA statistical software package (version 10.0. State Corporation, College State, TX) was used for analyses. Descriptive statistics characterizing the study population included calculation of the median and range for continuous variables and the frequency and percentiles for categorical variables. Associations between patient characteristics and the results of the SI were assessed using the chi square and Fisher’s exact test. All statistical tests were two-sided and considered to be statistically significant at p < 0·05.

Results

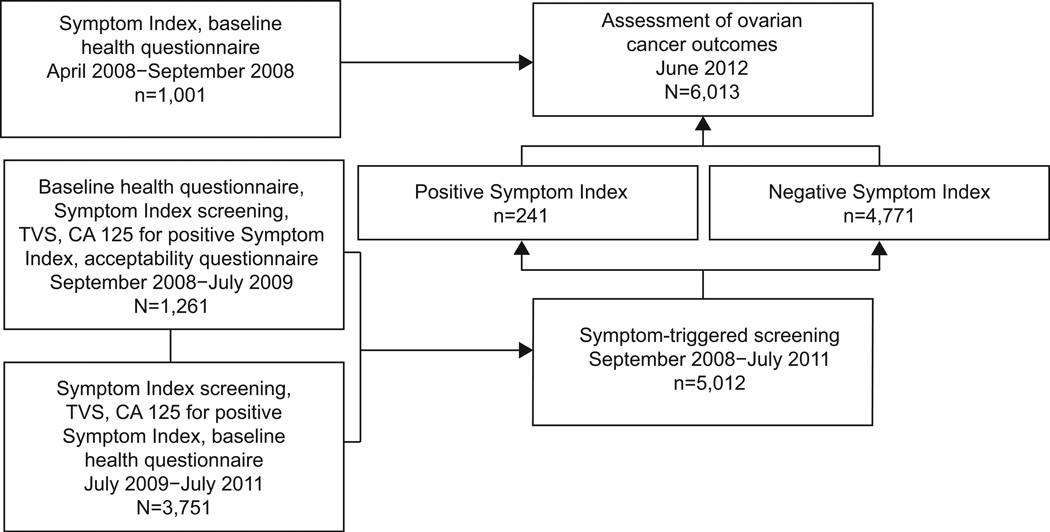

A total of 6,013 women were prospectively enrolled in the study (Figure 1) The first 1,001 were part of a feasibility pilot and used to refine the Symptom Index instrument.10 These women participated in the earliest pilot activities and filled out the Symptom Index and baseline health questionnaires, but were not offered transvaginal ultrasound or CA125. From 9/08–7/09, 1,261 women participated in symptom-triggered diagnostic evaluation with those being Symptom Index positive being offered transvaginal ultrasound and CA125.7The focus of this portion of the study was to establish patient and provider acceptability as well as rates of positive Symptom Index and subsequent testing. From 7/09–7/11 an additional 3,751 women were enrolled in the protocol to assess the consequences of proactive assessment of symptoms. All 6,013 women who filled out a Symptom Index had their cancer outcomes assessed in SEER are reported here.

Figure 1.

Enrollment in ovarian symptom study. TVS, transvaginal ultrasound.

In the 5,012 women who participated in the symptom-triggered diagnostic evaluation, 241 (4·8%) were Symptom Index-positive. Table 1 shows the demographics of the women who participated in the study. Of the 241 women who screened positive on the Symptom Index, 211 (88%) participated in additional testing with transvaginal ultrasound and CA125 (12% declined).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and Results of the Symptom Index

| Patient Characteristic and Health Condition |

Total* (n=5,012) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 40–50 | 1 |

| 50+ | 3 |

| Menopausal status | |

| Premenopausal | 401 (8) |

| Perimenopausal | 1,340 (27) |

| Postmenopausal | 3,054 (61) |

| Race | |

| White | 4,351 (87) |

| Black | 107 (2) |

| Asian | 168 (3) |

| Reason for visit | |

| Routine screen | 2,760 (55) |

| Routine follow-up | 645 (13) |

| I’m concerned about something | 1,248 (25) |

| Gynecologic condition | |

| Endometriosis | 287 (9.6) |

| Leiomyomas | 830 (17) |

| Ovarian cysts | 611 (12) |

| More than one of these conditions | 449 (9) |

| Medical conditions | |

| Irritable bowel disease | 418 (8) |

| Urinary tract infection | 568 (11) |

| Acid reflux | 994 (20) |

| Diabetes | 292 (6) |

| Hypertension | 989 (20) |

| Heart disease | 161 (3) |

| Thyroid disease | 828 (17) |

| More than one of these conditions | 1,438 (29) |

Data are n(%).

Percents calculated using column total and may not add up to 100% due to missing data.

Tables 2 and 3 show the results of the transvaginal ultrasound and CA125 tests performed in women with a positive Symptom Index. Of the 211 transvaginal ultrasounds ordered, 80 (38%) were also ordered as part of routine clinical care. Most (70%) were ordered because of pain with or without postmenopausal bleeding and the rest due to postmenopausal bleeding alone or suspicious examination. There were 24 indeterminate transvaginal-ultrasound scans (13 thickened endometrial stripes11 and 11 adnexal masses) and six scans that were reported as suspicious for cancer. There were 6 CA125 tests that were elevated above 35 U/ml: none were highly elevated.

Table 2.

Results for Transvaginal Ultrasound for Symptom Index-Positive Patients (n=211)

| Results | n |

|---|---|

| Not done | 14 |

| Normal | 93 |

| Abnormal | 104 |

| Likely benign | 74 |

| Indeterminate* | 24 |

| Thickened endometrial stripes | 13 |

| Adnexal Masses | 11 |

| Atypical leiomyoma | 1 |

| Benign ovarian cyst | 1 |

| Dermoid | 1 |

| Leiomyomas | 2 |

| Endometriomas | 2 |

| Resolved cysts | 4 |

| Suspicious† | 6 |

| Benign ovarian cyst | 1 |

| Endometrial cancer | 1 |

| Endometrioma | 1 |

| Ovarian fibroma | 1 |

| Renal cell cancer | 1 |

| Tuboovarian abcess | 1 |

14/24 scans done secondary to routine care.

5/6 scans done secondary to routine care.

Table 3.

Results of CA 125 for Symptom Index-Positive Patients (n=211)

| Result | n |

|---|---|

| Not Done | 2 |

| Normal (<35) | 203 |

Elevated

|

6 |

TVS, transvaginal ultrasound; TAH–BSO, total abdominal hysterectomy–bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; TVH–BSO, transvaginal hysterectomy–bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; TVH, transvaginal hysterectomy.

TVS scan done secondary to routine care.

While some of the follow-up procedures done on study participants were not based on concern or suspicion of ovarian cancer (e.g. the thickened endometrial stripes with postmenopausal bleeding), all subsequent proceedures are shown in Table 4. In total, there were 20 laparoscopies, laparotomies, or vaginal hysterectomies performed in study participants within 6 months of a positive Symptom Index (0.4% of participating women). However, only six (0.12%) were done for a suspicous ovarian mass. Overall, among study participants with positive Symptom Index results, there was a false-positive rate resulting in a major surgical procedure of 0.4% (20/5012) or 1 in 250 women (95% CI 1/162–1/410). As 14 of these surgeries were performed for clearly non-ovarian conditions in the absence of a transvaginal ultrasound or CA125 result deemed suspicious for ovarian cancer, the rate for surgical procedures associated with a positive follow-up test result in a Symptom Index positive woman was 0.012% (6/5012) or 1 woman out of 835 ( 95% CI 1/418–1/2005).

Table 4.

Procedures and Tests Performed in Study Participants

| Secondary to Study |

Routine Care | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endometrial biopsy | 8 | 22 | 30 |

| CA125 | 2 | 3 | 50 |

| Ultrasound | 6 | 17 | 23 |

| CT scan | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| MRI | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Hysteroscopy | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| Laparoscopy | 3 | 7 | 10 |

| TAH–BSO | 1 | 6 | 7 |

| Vaginal hysterectomy–BSO | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Other | 5 | 22 | 27 |

All data are n.

CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TAH-BSO, total abdominal hysterecomy–bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

Ovarian cancer outcomes were assessed for all 6,013 women through the Western Washington SEER Cancer Registry. As studies have shown that most ovarian cancer patients do not recognize symptoms until less than one year and more reliably 6 months prior to diagnosis, we were primarily interested in women who developed ovarian cancer within 6 months from participating in a symptom index. Table 5 shows the ovarian cancer outcomes for the study. There were two women who developed ovarian cancer within 6 months of completion of the Symptom Index. One was positive and was diagnosed 31 days later with distant disease (part of the 1,001 unscreened pilot group) and one who was Symptom Index negative was diagnosed with local disease. Of note, this Symptom Index negative patient had a family history of ovarian cancer and was being worked up as part of routine care for a pelvic mass at the time of her study participation. The other six patients with ovarian cancer were diagnosed 281–843 days (median 569 days) following participation in the study. Half of these patients (3/6) were diagnosed with regional disease.

Table 5.

Ovarian Cancer Outcomes

| Symptom Index | Number of Days Post-SI for Ovarian Cancer Diagnosis |

SEER Stage |

|---|---|---|

| SI+ | 31 | Distant |

| SI− | 78 | Local ( IA) |

| SI− | 281 | Regional |

| SI− | 300 | Regional |

| SI− | 371 | Distant |

| SI− | 804 | Distant |

| SI− | 815 | Regional |

| SI− | 843 | Distant |

SI, Symptom Index; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Also of potential interest, 80 (38%) of the transvaginal ultrasound and 26 (12%) of the CA125s done in the Symptom Index positive women were also ordered by clinic physicians as part of routine clinical care, based on their personal clinical judgment separate from our study activities. While there were 20 major surgical procedures performed, only three laparoscopies and one laparotomy were performed soley due to participation in the study. Of the four procedures, one dermoid, two endometriomas and one atypical leiomyoma was diagnosed. One patient who underwent a laparoscopy developed a postoperative wound infection. Overall, this corresponds to a false-positive rate for major surgery of 0.08% (4 of 5,012), or 1 of every 1,253 women evaluated (95% CI 1/489–1/4599).

Discussion

Currently there are no organizations that recommend screening for ovarian cancer in the general population.1,2,3 The U.S. Preventive Service Task Force (USPTF) reissued their grade D recommendation in 2012 (15) based largely on the results from the Prostate Lung Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening trial which was reported in 2011.12 A second large screening trial from the UK has also shown that using a transvaginal ultrasound as part of the initial screen results in a significant false-positive rate and high rates of probable unindicated surgeries,13 reinforcing that transvaginal ultrasound should be used as a diagnostic but not a screening test.

In our study population symptom-triggered diagnostic evaluation resulted in 0.4% (20/5012) of women undergoing surgery, 80% (16/20) of these were done for clinical indications, and only 4/20 (20%) were performed solely due to participation in the study. This rate of false-positive surgery 0.08% (1 of every 1,253 women evaluated), is important as concerns have been raised that monitoring for symptoms associated with ovarian cancer could lead to high rates of unindicated procedures. Although there is a low rate of potentially unindicated surgery the possibility that symptom screening could lead to a 20% (4/20) increase in surgery must be considered a potentially negative consequence. However, although these were false postives for ovarian cancer, each of these patients did have pelvic pathology and the surgery may have prevented future problems.

The efficacy of a symptom-triggered approach cannot be adequately assessed in this study because of the low number of ovarian cancers. There were only two cases of ovarian cancer diagnosed within 6 months of Symptom Index completion. This is the time window when most non-recall biased studies show that patients begin to experience and report symptoms.14,15,16,17 Only one of the patients diagnosed within 6 months had a positive Symptom Index and she had advanced stage disease, therefore no patients were diagnosed with early stage disease within 6 months. The other 6 patients were diagnosed beyond 6 months. If we had used 12 months as a cut off, then only 1 of 4 (25%) would have been identified through symptoms. Fortunately, only 4.8% of participants were Symptom Index positive and therefore, if universal symptoms screening was found to be an effective method to identify women who should receive diagnostic evaluations for ovarian cancer, then more than 95% of women would not require any testing. However, if symptoms were to be used as a the only means of screening for ovarian cancer the sensitivity of a symptom based screening program would be low and would need to be improved, possibly though more frequent screening or the addition of biomarkers to a multi-modal strategy.

Long-term follow-up of study participants identified six women who developed ovarian cancer more than 6 months after their participation in the study. Of these six women, three had their ovarian cancers identified at regional stage. While it is impossible to determine the details leading to this better than would be expected stage distribution in women who had previously participated in our study, and it is possible that with such a small sample this result is coincidental, it may be possible that study participation provided these women with valuable education about ovarian cancer symptoms spurring them to seek evaluation of subsequent symptoms that were associated with the cancers they eventually developed. Such a result would be consistent with the findings of Gilbert et al,14 who found that prompt aggressive evaluation of approximately 1,500 women with symptoms resulted in an ovarian cancer prevalence ten times greater than the general population and an improved prognosis in a majority of cases.

In the Diagnosing Ovarian Cancer Early (DOvE) study, women were recruited through radio, newsprint and flyers.18 Women who met symptom entry inclusion criteria were offered a CA125 and transvaginal ultrasound within two weeks. If the CA125 was inderminant it was repeated in four weeks. If it was normal and women persisted in having symptoms the CA125 was repeated in four months. Of the 1,455 women enrolled, 11 or 1/132 women had ovarian cancer. Of the 11 cases diagnosed, four (36%) had early stage disease; four (36%) had small volume Stage III disease that was optimally cytoreduced; and three (27%) had advanced suboptimally cytoreduced disease. Comparison to the general clinic population in Montreal found that 56% of the ovarian cancer population was advanced suboptimally cytoreduced at the time of diagnosis. Also, in the study population 11 endometrial cancers were diagnosed as a result of thickened endometrial stripe11 and postmenopausal bleeding; therefore, one out of every 66 symptomatic women in this study was diagnosed with a gynecologic malignancy. Both the Gilbert, et al and our study emphasize need to further study prompt response to symptoms as a low cost method to triage women for diagnostic tests.

Limitations to our study include the low number of cancers which limits the ability to evaluate sensitivity, specificity and the potential for early diagnosis. However, with 5,000 screens we only expected 2–3 cancers to be diagnosed within 6 months of a positive Symptom Index. Other limitations include the fact that ultrasonographers knew patients were in a study and may have done a more thorough evaluation of adnexa. Providers were also aware of patient participation, which may reduce the external validity of the study. In a different setting, physician and patient concerns could drive the rate of surgical intervention higher. In addition, we did not have a control group who did not participate in a symptom-triggered evaluation so that surgical interventions could be compared.

Overall, we found that proactive symptom-triggered diagnostic evaluation would increase rates of potentially unindicated surgery by one patient in 1,253 evaluated. We found that 50% of the ovarian cancers detected in our study population were diagnosed in local or regional stages. While our numbers are small, based on SEER statistics only 20–30% are expected to be found in this more favorable stage category. While the actual symptom-triggered evaluation process may not have led to earlier diagnosis, it is speculated that some of these cancers may have been diagnosed early because women had increased awareness of symptoms which may have prompted them to seek care earlier resulting in identification of ovarian cancer at an earlier stage. The real value of a Symptom Index may lie in its ability to act indirectly as an educational tool.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a Gynecologic Cancer Foundation/Ovarian Cancer Research Foundation Grant for Early Detection of Ovarian Cancer (PI: Goff) and by grant number R21NR011571 from the National Institute of Nursing Research (PI: Andersen). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Nursing Research or the Gynecologic Cancer Foundation.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

M. Robyn Andersen, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and School of Public Health and Community Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle WA.

Kimberly A. Lowe, Exponent Health Sciences Seattle WA.

Barbara A. Goff, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA.

References

- 1.Committee Opino No. 477. The role of the obstetrician-gynecologist in the early detection of epithelial ovarian cancer. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on gynecologic Practice. March 2011. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(3):742–746. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821477db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schorge JO, Modesitt SWC, Coleman RL, et al. SGO White Paper on ovarian cancer: etiology, screening and surveillance. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119(1):7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Screening for Ovarian Cancer, Topic Page. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. US Preventive Services Task Force Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goff BA, Mandel L, Muntz HG, Melancon CH. Ovarian carcioma diagnosis. Cancer. 2000;89(10):2068–2075. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001115)89:10<2068::aid-cncr6>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goff BA, Mandel LS, Melancon CH, Muntz HG. Frequency of symptoms of ovarian cancer in women presenting to primary care clinics. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2705–2712. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goff BA, Mandel LS, Drescher SW, et al. Development of an ovarian cancer symptom index: possibilities for earlier detection. Cancer. 2007;109(2):221–227. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersen MR, Goff BA, Lowe KA, et al. Combining a symptoms index with CA125 to improve detection of ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2008;113(3):484–489. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersen MR, Goff BA, Lowe KA, et al. Use of a symptom index, CA1215, and HE4 to predict ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116(3):378–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.10.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goff A, Lowe KA, Kane JC, Robertson MD, Gaul MA, Andersen MR. Symptom triggered screening for ovarian cancer: a pilot study of feasibility and acceptability. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124(2):230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersen RM, Goff B, Lowe K. Development of an instrument to identify symptoms potentially indicative of ovarian cancer in a primary care clinic setting. OJOG. 2012;2:183–191. [Google Scholar]

- 11.The role of transvaginal ultrasonogrpahy in the evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding. ACOG Committee Opinon No. 440. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obset Gynecol. 2009;114:409–411. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b48feb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buys SS, Partridge E, Black A, et al. Effect of screening on ovarian cancer mortality: the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2011;305(22):2295–2303. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menon U, Gentry-Maharaj A, Hallett R, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of multimodal and ultrasound screening for ovarian cancer, and stage distribution of detected cancers: results of the prevalence screen of the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS) Lancet Ooncol. 2009;10(4):327–340. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamilton W, Peters TJ, Bankhead C, Sharp D. Risk of ovarian cancer in women with symptoms in primary care: population based case-control study. BMJ. 2009;339:b2998. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith LH, Morris CR, Yasmeen S, Parikh-Patrl A, Cress RD, Romano PS. Ovarian cancer: can we make the clinical diagnosis earlier? Cancer. 2005;104(7):1398–1407. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freidman GD, Skilling JS, Udalstove NV, Smith LH. Early symptoms of ovarian cancer: a case-control study without recall bias. Fam Pract. 2005;22(5):548–553. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossing MA, Wicklund KG, Cushing-Haugen KL, Weiss NS. Predictive value of symptoms for early detection of ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(4):222–229. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilbert L, Basso O, Sampalis J, et al. Assessment of symptomatic women for early diagnosis of ovarian cancer: results from the prospective DOvE pilot project. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):285–291. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70333-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]