To the Editors:

Renewed emphasis on the design of personalized treatment regimens for patients with bipolar disorder raises the importance of identifying baseline factors that can predict response in each patient. Such factors, termed moderators, identify patient subgroups with different treatment effect sizes.1 Given the lack of validated moderators in psychiatry, the National Institute of Mental Health has released a call for future clinical trials in psychiatry to evaluate moderators of treatment response.2 Predictors, on the other hand, are pretreatment variables that are associated with final outcome regardless of treatment assignment but are not uniformly controlled for possible placebo effects or spontaneous improvement. Established predictors of poor outcome in bipolar disorder include early age of onset, mixed states, psychosis, substance abuse, medication nonadherence, and the presence of comorbid anxiety disorders.

Metabolic syndrome, as defined by the Adult Treatment Panel III of the National Cholesterol Education Program, is the combined presence of at least 3 of the following routinely measured variables linked to insulin resistance: abnormal waist circumference, hypertriglyceridemia, low levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, glucose intolerance, and hypertension. More than one third of patients with bipolar disorder meet the criteria for metabolic syndrome and develop these risk factors at an earlier age than individuals without psychiatric illness.3,4 However, screening for metabolic syndrome, even among those receiving atypical antipsychotic agents, has been estimated to occur in less than one third of all patients.5 Metabolic syndrome can be evaluated as a moderator or a predictor of treatment outcome or stabilization status to determine the impact of this pretreatment characteristic on psychiatric treatment outcomes. Interest in medical comorbidity and its influence on treatment outcomes in patients with psychiatric conditions such as bipolar disorder has recently received increasing attention, perhaps owing to differing effects of second-generation antipsychotic drugs on cardiometabolic health, metabolic syndrome, and its components. Although some studies that have explored the relationship between general medical comorbidity and response to treatment have shown inconsistent findings, a detailed investigation of specific medical risk factors found that greater depression severity was associated with higher levels of triglycerides but only among patients who met the criteria for metabolic syndrome.6 The finding raises the question of whether cardiometabolic illnesses can uniquely influence psychiatric outcomes through common pathophysiological mechanisms.

Data collected during a previously reported 26-week study in patients with Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition bipolar I disorder7 were recently used to estimate the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in participants who were initially stabilized with open-label aripiprazole for up to 18 weeks and then randomized to aripiprazole versus placebo for a maintenance phase of 26 weeks.8 The analysis showed that 36% of patients with bipolar disorder entered the maintenance phase of this study with metabolic syndrome. The prospective nature of this maintenance trial presented the opportunity to determine the prevalence of metabolic syndrome at baseline and up to 18 weeks after treatment. It also allowed for testing whether metabolic syndrome status is associated with the likelihood of achieving clinical psychopathological stabilization. Before performing this post hoc analysis, we hypothesized that (1) patients meeting the metabolic syndrome criteria at base-line would be less likely to achieve stabilization and that (2) open-label treatment with aripiprazole would be associated with a decreased rate of metabolic syndrome in patients switching from other bipolar treatment options to aripiprazole. This current post hoc analysis focuses on data collected during the stabilization phase of 18 weeks or less for this maintenance trial, in which subjects met the stabilization criteria while on open-label aripiprazole (15 or 30 mg/d).

Details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria have been previously published.7 Participants were eligible for entry into the stabilization phase of the study from a number of sources,7 although the analyses presented herein used only the de novo patient population; those who were rolled over from a prior study of aripiprazole were excluded from these analyses. All psychotropic medications, except lorazepam and anticholinergic agents, were discontinued before enrolment.

Metabolic syndrome was defined according to the modified National Cholesterol Education Program III criteria9 thresholds for abnormal metabolic measures, although a body mass index of 30 or greater was substituted in lieu of missing waist circumference data in some patients. Data on treatment for abnormal metabolic values were not available. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome was calculated at entry into the stabilization phase and at stabilization phase end point. The association of metabolic syndrome with clinical psychopathological stabilization during aripiprazole treatment was evaluated using Fisher exact test on 2 × 2 frequency tables of stabilization status (stabilized/not stabilized) versus metabolic syndrome status (present/ absent) using last observation carried forward (LOCF) data. Stabilization was defined as a Young Mania Rating Scale total score of 10 or lower and a Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale total score of 13 or lower maintained for the previous consecutive visits during the stabilization phase, evaluated on an LOCF basis. Differences in rates of metabolic syndrome and its 5 individual components at stabilization phase baseline and end point were evaluated using McNemar test on 2 × 2 frequency tables of baseline status (present/ absent) versus end point status (present/ absent) using LOCF data. For the determination of metabolic syndrome status, the last available observation for each of the 4 components was selected. Therefore, the 5 components used for evaluation may not necessarily have been measured at the same time point. To test the effects of prior use of treatment with mood stabilizers, atypical antipsychotic agents, antidepressants, or typical antipsychotic agents on rates of metabolic syndrome, analyses stratified by psychotropic medication were also performed.

The flow of participants throughout each phase of the study and baseline demographics and clinical features have been presented in prior articles.7,10 At stabilization phase baseline, de novo patients (n = 139) had a mean T SD age of 39.5 T 11.9 years; most were women (66.2%) and white (69.8%), a high proportion were Hispanic patients (20.9%), 16.5% had a diagnosis of rapid cycling, and 60.9% were experiencing a current manic episode. The mean T SD weight was 84.6 (21.1) kg. These baseline demographic characteristics were similar to those of the total population.7 The mean stabilization phase time was 12.7 weeks; the mean dosage of aripiprazole was 25.2 mg/d. At stabilization phase baseline, 45% (62/139) of patients met the criteria for metabolic syndrome, whereas 55% (77/139) did not meet the criteria. For each of the different components of metabolic syndrome, most patients had no changes in their metabolic status during treatment, although waist circumference in women, HDL cholesterol level in men, and blood pressure in all patients showed significant differences in rates at stabilization phase baseline and end point (all P G 0.05). Notable switches from abnormal baseline to normal end point values were 17.4% of patients with abnormal blood pressure, 19.6% of women with abnormal waist circumference, and 21.7% of men with an abnormal HDL cholesterol level. Of the 62 patients with metabolic syndrome at stabilization phase baseline,31 (50%) met the clinical psychopathological stabilization criteria by end point (week 18 or earlier), and 31 (50%) did not. Among patients with metabolic syndrome at end point (week 18 or earlier), 52% (24/46) met the stabilization criteria, and 48% (22/46) did not.

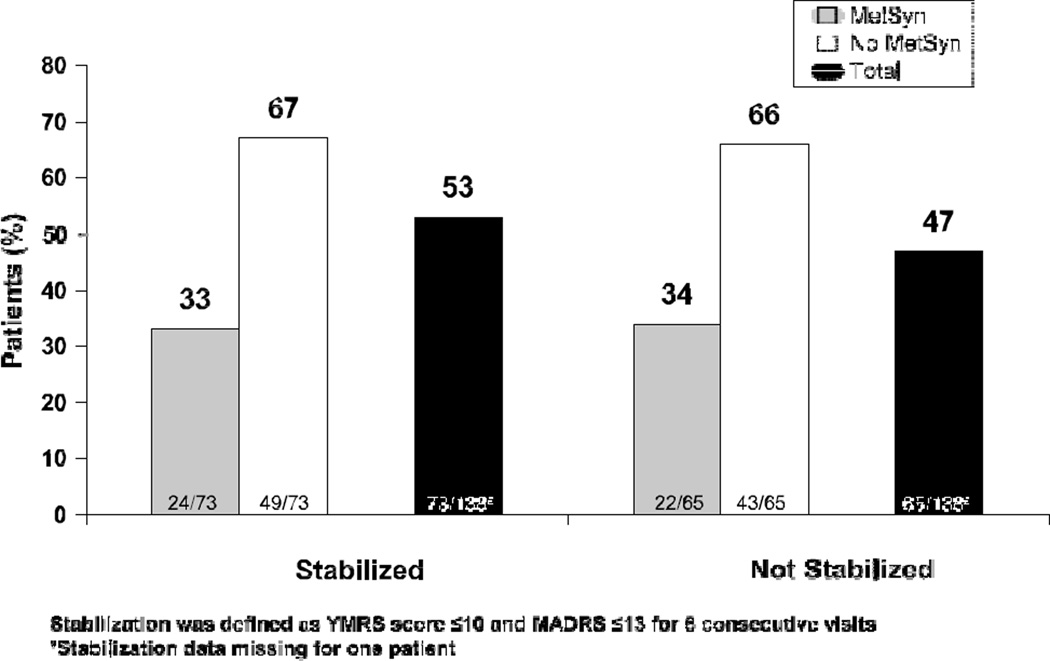

The prevalence of metabolic syndrome at stabilization phase end point (week 18 or earlier) did not differ between patients who were and were not stabilized at end point (P 9 0.999; Fig. 1). After aripiprazole treatment for up to 18 weeks, there was a significant decrease in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome at the end of the stabilization phase compared with baseline (45% vs 33%, P = 0.01). Of those patients who were stabilized at end point, 47.6% were obese. Of those not stabilized, 44.7% were obese. More patients treated with prior atypicals retained metabolic syndrome when switched to aripiprazole during stabilization in this study than patients treated with a prior mood stabilizer atypical combination or mood stabilizer alone (66.7% vs 47.6% and 38.5%, respectively). For the stratified analysis of prior medications, the metabolic syndrome rate was significantly reduced for subjects discontinuing mood stabilizers (P = 0.004), defined as lithium, valproate, lamotrigine, or carbamazepine. The remaining drug categories, which included patients discontinuing atypical antipsychotic monotherapy, showed no significant changes.

FIGURE 1.

Proportion of patients by clinical stabilization at end point with and without metabolic syndrome

This is believed to be the first study to specifically examine the effect of metabolic syndrome status on treatment out-come among patients with bipolar I disorder experiencing a recent manic or mixed episode. The presence of metabolic syndrome at baseline was not identified as a predictor of clinical psychopathological stabilization during open-label treatment with aripiprazole. In contrast to some previous studies, the findings from this analysis do not support an association between metabolic syndrome and higher or lower rates of immediate stabilization with aripiprazole. Although this analysis does not allow the conclusion that metabolic syndrome can be applied as a predictor of stabilization, it did reveal a significant decrease in the rate of metabolic syndrome for patients discontinuing other psychotropic medications, particularly mood stabilizers. This is not surprising, as a recent trial in schizophrenia showed that switching patients from an antipsychotic agent with high liability for weight gain and dyslipidemia to aripiprazole resulted in significant reductions in body weight and fasting triglyceride levels.11

Several components of metabolic syndrome, namely, waist circumference in women, HDL cholesterol in men, and Blood pressure in all patients, showed significant differences in rates at stabilization phase baseline and end point, suggesting a shift toward normal values. Indeed, for patients remaining on aripiprazole for up to 26 weeks during the subsequent blinded maintenance phase of this trial, the proportion meeting the criteria for metabolic syndrome, or any of its individual components, did not differ from placebo.8 Undoubtedly, preventing and decreasing metabolic risk factors lessens the morbidity and the mortality associated with general medical illnesses and may enhance the psychological well-being of patients and possibly improve the long-term course of bipolar disorder. The findings of the current analysis lend support to some potential beneficial effects of aripiprazole on metabolic health status for patients with bipolar disorder. Few clinical trials in bipolar disorder have examined the impact of medical comorbidity on stabilization outcomes, and even fewer have focused on the specific effect of metabolic syndrome. The exploratory methods of this investigation are consistent with hypothesis-generating efforts to identify patients for whom a specific treatment is most likely to be effective. The identification of predictors or moderators of treatment can aid in refining the inclusion/exclusion criteria of future studies and validate stratification variables for random allocation. Although the first part of our hypothesis was not proven and findings suggest that metabolic syndrome or obesity is not associated with worsened clinical outcome with aripiprazole, the results should not discourage investigators from examining whether other conditions can predict or moderate bipolar outcomes. There are several reasons why our analysis may not have generated statistically significant findings regarding metabolic syndrome or obesity as predictors of treatment outcome one of which being that metabolic syndrome, as a cluster of cardio-metabolic risk factors, may function as an imprecise predictor of treatment response. Nonetheless, it is notable that patients treated with open-label aripiprazole showed an improvement in metabolic status and individual metabolic syndrome components.

As with all post hoc analyses, there are limitations, and future prospective studies to evaluate moderators of treatment response, as recommended by the National Institute of Mental Health, will be of further clinical value. Limitations include the following: body mass index as a proxy measure of abdominal obesity was used for some patients; these results may not extend to patients treated with medications other than aripiprazole; and patient numbers for analysis of data by drug category were too small to warrant conclusions. Strengths include the following: the prospective design, which enabled calculation of differences in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome over time, and the conservative criteria used to define stabilization. The sizable enrolment of Hispanic participants is a strength regarding the generalizability, as race has a significant impact on metabolic risk.12 In conclusion, baseline metabolic syndrome status was not predictive of clinical psychopathological stabilization in this population of patients with bipolar disorder experiencing a recent manic or mixed episode. Metabolic syndrome incidence after approximately 12 weeks of aripiprazole treatment was reduced significantly.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb Company (Princeton, NJ) and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd (Tokyo, Japan). Editorial support for the preparation of this article was provided by Ogilvy Health world Medical Education; funding was provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Footnotes

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE INFORMATION

David Kemp is on the speaker’s bureau of AstraZeneca, Pfizer and a consultant of BMS. James Eudicone, Jessie Chambers, and Ross Baker are employees of Bristol-Myers Squibb. Robert McQuade is an employee of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development and Commercialization, Inc.

Contributor Information

David E. Kemp, University Hospitals Case Medical Center Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH kemp.david@gmail.com.

James M. Eudicone, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Plainsboro, NJ.

Robert D. McQuade, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Development & Commercialization Inc, Princeton, NJ.

Jessie S. Chambers, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Plainsboro, NJ.

Ross A. Baker, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Plainsboro, NJ.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kraemer HC, Frank E, Kupfer DJ. Moderators of treatment outcomes: clinical, research, and policy importance. JAMA. 2006;296:1286–1289. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.10.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Insel TR. Translating scientific opportunity into public health impact: a strategic plan for research on mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:128–133. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fagiolini A, Frank E, Scott JA, et al. Metabolic syndrome in bipolar disorder: findings from the Bipolar Disorder Center for Pennsylvanians. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:424–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fagiolini A, Frank E, Turkin S, et al. Metabolic syndrome in patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:678–679. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0423c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haupt DW, Rosenblatt LC, Kim E, et al. Prevalence and predictors of lipid and glucose monitoring in commercially insured patients treated with second generation antipsychotic agents. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:345–353. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richter N, Juckel G, Assion HJ. Metabolic syndrome: a follow-up study of acute depressive inpatients. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;260:41–49. doi: 10.1007/s00406-009-0013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keck PE, Calabrese JR, McQuade RD, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 26-Week trial of aripiprazole in recently manic patients with bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:626–637. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kemp D, Calabrese J, Tran Q, et al. Metabolic syndrome in patients enrolled in a clinical trial of aripiprazole in the maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05159gre. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–2752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keck PE, Calabrese JR, McIntyre RS, et al. Aripiprazole monotherapy for maintenance therapy in bipolar I disorder: a 100-week, double-blind study versus placebo. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1480–1491. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newcomer JW, Campos JA, Marcus RN, et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind study of the effects of aripiprazole in overweight subjects with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder switched from olanzapine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1046–1056. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carroll JF, Chiapa AL, Rodriquez M, et al. Visceral fat, waist circumference, and BMI: impact of race/ethnicity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:600–607. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]