Abstract

Objective

To examine the relation of physical activity practices covering physical education (PE), recess, and classroom time in elementary schools to children’s objectively measured physical activity during school.

Methods

Participants were 172 children from 97 elementary schools in the San Diego, CA and Seattle, WA USA regions recruited in 2009–2010. Children’s moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) during school was assessed via accelerometry, and school practices were assessed via survey of school informants. Multivariate linear mixed models were adjusted for participant demographics and unstandardized regression coefficients are reported. The 5 practices with the strongest associations with physical activity were combined into an index to investigate additive effects of these practices on children’s MVPA.

Results

Providing ≥100 minutes/week of PE (B = 6.7 more minutes/day; p = .049), having ≤ 75 students/supervisor in recess (B = 6.4 fewer minutes/day; p = .031), and having a PE teacher (B = 5.8 more minutes/day; p = .089) were related to children’s MVPA during school. Children at schools with 4 of the 5 practices in the index had 20 more minutes/day of MVPA than children at schools with 0 or 1 of the 5 practices (p < .001).

Conclusions

The presence of multiple school physical activity practices doubled children’s physical activity during school.

Keywords: accelerometry, physical education, policy, recess

Schools are recommended to provide physical activity opportunities to contribute to children meeting the 60 minutes/day moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) guideline (CDC 2011, Koplan, Liverman and Kraak 2005, Pate et al. 2006, USDHHS 2008). Recommendations for elementary schools are to provide children with ≥ 30 minutes/day of MVPA through Physical Education (PE), recess and other opportunities. Recommendations are ≥ 20 minutes of recess/day, ≥ 150 minutes of PE/week, and ≥ 50% of PE time be spent in MVPA (CDC 2011, Koplan et al. 2005, Pate et al. 2006). However, few U.S. public schools report meeting the PE recommendations, and approximately two thirds report meeting recess recommendations (Turner et al. 2010).

Previous studies have found that children’s physical activity during school is related to characteristics of the physical environment, such as availability and condition of gymnasium facilities (Sallis et al. 2001). School physical activity practices, which represent a direct measure of the opportunities that schools provide for physical activity, regardless of formal and informal policies, have been less studied. Evidence supports school practices such as active PE (e.g., SPARK) (McKenzie et al. 1996, Sallis et al. 1997) and classroom physical activity breaks (Donnelly et al. 2009, Mahar et al. 2006), but studies have typically examined single interventions (e.g., PE), rather than multiple practices. Survey studies have described school practices such as minutes allocated for PE and recess (Lee et al. 2007, Turner et al. 2010), but seldom have these practices been investigated relative to children’s physical activity.

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the relation of existing school physical activity practices covering PE, recess and classroom activities, to children’s objectively measured physical activity during school. It was hypothesized that children who attended schools with more practices supportive of physical activity, particularly those related to PE and recess, would accumulate more minutes/day of MVPA.

METHODS

Study design and participants

Participants were children enrolled in the Neighborhood Impact on Kids (NIK) and MOVE studies. NIK was a longitudinal observational study that investigated the relation of neighborhood built environment attributes to physical activity, nutrition, and obesity and included 723 children. The children were aged 8–13 years at 2-year follow-up, which was the assessment period used in the present study. Participants were recruited by telephone from selected neighborhoods in the Seattle/King County, WA and San Diego County, CA USA metropolitan areas (Saelens et al. 2012).

MOVE was a recreation center-based obesity prevention program that included 541 children from San Diego County, CA USA (Elder et al. under review). Children were aged 8–11 years at the 2-year follow-up, the assessment period used in the present study. Recruitment occurred around 30 public recreation centers using phone calls, flyers, presentations, and staffed information booths. The MOVE obesity prevention program included educational sessions at recreation centers and did not target schools or physical activity during school. The MOVE obesity prevention program did not significantly increase children’s MVPA (Elder et al. under review).

Exclusion criteria for the NIK and MOVE studies were similar: having a medical and/or psychological condition that affected diet, physical activity, growth or weight; and not being able to read and speak English or Spanish. There were no BMI criteria for enrollment. Child physical activity data for the present study were from NIK and MOVE assessments conducted during the 2009–2010 school year. Consent was obtained from parents and assent from children, and both studies were approved by the sponsoring universities’ Institutional Review Boards. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Some children completed the accelerometer assessment (main study outcome) when school was not in session (e.g., summer, holiday), so accelerometer data from days when school was not in session were excluded from the present analyses.

School informants

During the spring of 2012, PE teachers, or principals when there was no PE teacher, from the elementary schools attended by NIK and MOVE participants were contacted to complete a questionnaire assessing their school practices about physical activity. The focus of the present study was elementary school-aged youth, so middle schools were excluded. Prior to contacting school informants, school district officials were contacted to request permission to contact individual schools. Approval was obtained from 25 of the 28 districts contacted; the 3 districts that declined to participate were large districts in San Diego County.

Final study sample

Overall, NIK and MOVE included 1264 participants. After excluding middle schools, participants who completed assessments when school was not in session, and schools within the 3 San Diego districts that declined to participate, the potential sample size for the present study was 297 child participants from 154 schools. Complete survey responses were received from 63% of the informants contacted, resulting in a final sample size of 172 child participants from 97 schools.

Measures

Children’s physical activity

Participants wore waist-worn Actigraph accelerometers, which have good validity for assessing physical activity in children (Welk, Corbin & Dale 2000). Instructions were to wear the device for 7 days during all waking hours. NIK used Actigraph model GT1M and Move used Actigraph models 7164 and GT1M, all set to record acceleration at 30-second epochs. Minutes of physical activity were calculated using the 4-MET Freedson age-based thresholds (Freedson, Pober & Janz 2005) which have been used for national prevalence estimates (Troiano et al. 2008). Weekend days were excluded, and school start and end times unique to each individual school were used to calculate minutes/day of MVPA during school, thus eliminating non-school time from the analysis. Days with any nonwear time during school were removed from the analysis, with nonwear time defined as ≥ 20 minutes of consecutive 0 counts.

Children’s demographic characteristics

Parents reported their highest education level attained and their child’s school name, grade level, gender, and race/ethnicity.

School demographic characteristics

State Department of Education data were used to identify each school’s percent of students that were white non-Hispanic and percent eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, as well as the total number of teachers and students (California Department of Education 2012, State of Washington 2012).

School physical activity practices

The school physical activity practice items were selected from the School Physical Activity Policy Assessment (S-PAPA) tool (Lounsbery et al. 2012), and some adaptations were made. The survey was kept brief to limit burden and increase participation; items relevant to PE, recess, and classroom physical activity that were expected to have the largest reach and associations with physical activity were retained. The practices assessed included whether 1) the school had a PE teacher (could include a PE aide), 2) training was provided to increase MVPA in PE, 3) recess was supervised by a classroom teacher, 4) organized activities (e.g., walking programs, games) were provided during recess, 5) classroom teachers were provided training on classroom physical activity breaks, and 6) classroom teachers implemented classroom physical activity breaks. Informants also reported the 7) number of minutes/PE lesson and 8) number of lessons/week of PE, 9) number of students/PE lesson, 10) average length of recess periods, and 11) average number of students/supervisor during recess. In schools without a PE teacher, classroom teachers were responsible for holding PE. The minutes/PE lesson item was multiplied by the number of PE lessons/week item to determine number of PE minutes/week. Because state laws (California State Board of Education 1999, National Cancer Institute 2011) and formal guidelines (CDC 2011, National Association for Sport and Physical Education 2012, Pate et al. 2006) exist for PE minutes/week and recess minutes/day, these variables were dichotomized as ≥ 100 minutes/week for PE (the mandated amount in California and Washington) and ≥ 20 minutes/period for recess. The PE class size and recess students/teacher items were explored as continuous and dichotomous variables (different cut points were tested), and the stronger correlates of during-school MVPA were retained in the analysis.

School informants were instructed to consider 5th grade classes when responding to the survey questions, because this was the average grade of the children in the study sample. Informants were also instructed to consider the 2009–2010 school year when completing the survey and were asked if they were working for their current school during 2009–2010.

Analyses

Spearman correlations were used to investigate relationships among the physical activity practices. A three-level mixed effects linear regression model was used to investigate the relation of school practices to children’s minutes/day of MVPA during school (model 1). Days of accelerometer monitoring within participants was used as a level of analysis, in addition to participants within schools, to improve study power, rather than averaging MVPA across days within a participant. A school physical activity practice index was derived to represent the number of practices each school reported from a list of practices that had an effect size >|2.5| minutes/day of MVPA in model 1. School practices with effect sizes >|2.5| in model 1 were considered to be important to children’s physical activity, and the purpose of the index was to explore if there were additive rather than substitutive effects of having multiple school physical activity practices. A second three-level mixed effects linear regression model was used to investigate the relation of the school practices index to children’s MVPA during school (model 2). Both models adjusted for child age, gender, accelerometer model, study, and intervention condition (for MOVE participants). All independent variables and covariates were centered on zero (i.e., 0.5 vs. −0.5) with the exception of age which was grand mean centered. Unstandardized coefficients were reported and can be interpreted as minutes/day of MVPA.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents characteristics of the child participants and elementary schools in the final study sample. BMI, race/ethnicity and parent education for the subsample used in the present study were within 5% of the overall samples that were part of NIK and MOVE, with the exception that the overall MOVE sample had 7% more Latinos than the present subsample. Table 2 presents the percent of schools with each practice and the correlations among the practices. Schools reported providing an average of 81.4 (SD = 42.6) minutes/week of PE and 19.4 (SD = 4.2) minutes/period of recess. There were an average of 38.9 (SD = 63.7) students/lesson in PE and 69.1 (SD = 40.7) students/supervisor in recess.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Child characteristics | |

| Total number of children | 172 |

| Percent girls | 51.7 |

| Percent in 5th grade | 44.5 |

| Mean (SD) age | 10.2 (1.5) |

| Percent overweight or obese | 27.3 |

| Percent of children white non-Hispanic | 69.2 |

| Percent with a parent who has a college degree | 63.8 |

| Percent with ≥ 2 days of accelerometer monitoring | 91.3 |

| Mean (SD) school days of accelerometer monitoring/child | 3.7 (1.7) |

| Percent wore GT1M accelerometer | 91.3 |

| Percent from San Diego | 48.3 |

| Percent from MOVE study | 20.3 |

| Mean (SD) MVPA during school | 29.4 (16.2) |

| Percent with ≥ 30 minutes/day of MVPA during school | 45 |

| Elementary school characteristics | |

| Total number of schools | 97 |

| Percent of informants employed during accelerometer collectiona | 83.3 |

| Percent of schools with ≥ 2 child participants | 37.1 |

| Mean (SD) child participants/school | 1.8 (1.5) |

| Percent of schools in San Diego | 49.5 |

| Percent of schools private schools | 12.4 |

| Mean (SD) FRPL eligible | 30.8 (24.5) |

| Mean (SD) full time teachers/school | 26.9 (6.5) |

| Mean (SD) total students/school | 549 (166) |

| Mean (SD) percent of students white non-Hispanic | 53.7 (21.0) |

| Total number of school districts included | 25 |

| Mean (SD) length of school day (hours:minutes) | 6:24 (0:15) |

Note:

Accelerometer data were collected during the 2009–2010 school year and school informants provided information on school practices in Spring, 2012

Abbreviations: SD = standard deviation; FRPL = free or reduced price lunch; MVPA = moderate to vigorous physical activity

Data from San Diego, CA and Seattle, WA USA, 2009–2010

Table 2.

Frequencies of and Spearman correlations among elementary school physical activity practices (N = 97 schools)

| Percent of schools with practice | Spearman r

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| 1. PE teacher | 72.9 | −.44** | .40** | .51** | .24** | −.03 | −.23** | −.21** | −.16** | −.08* |

| 2. ≥ 100 minutes/week of PE | 18.8 | - | −.44** | −.27** | −.36** | .05 | .25** | .14** | .16** | .19** |

| 3. ≤ 30 students/lesson in PE | 66.7 | - | - | .22** | .23** | −.15** | −.21** | −.06 | −.24** | −.06 |

| 4. Training on MVPA in PE | 59.4 | - | - | - | .01 | −.09* | −.10* | −.04 | −.01 | −.05 |

| 5. Recess supervised by non-classroom teacher | 78.1 | - | - | - | - | .05 | −.08* | −.09* | −.11* | −.05 |

| 6. ≥ 20 minutes/period of recess | 58.3 | - | - | - | - | - | −.06 | −.05 | .04 | .09* |

| 7. ≤ 75 students/supervisor in recess | 78.1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | .25** | .09* | .14** |

| 8. Activities provided during recess | 46.9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | .14** | .12* |

| 9. Training on MVPA in classroom | 15.6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | .25** |

| 10. Implementation of MVPA in classroom | 54.2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Note: All items were yes/no items where yes = 1 and no = 0;

p <.05;

p <.001

Abbreviations: PE = physical education; MVPA = moderate to vigorous physical activity

Data from San Diego, CA and Seattle, WA USA, 2009–2010

The multivariate relations of practices to children’s minutes/day of MVPA are presented in Table 3. Children at schools that provided ≥ 100 minutes/week of PE had 6.7 more minutes/day of MVPA during school (p = .049). Children at schools that had ≤ 75 students/supervisor in recess had 6.4 fewer minutes/day of MVPA during school (p = .031).

Table 3.

Multivariate relations of elementary school physical activity practices to children’s objectively measured minutes/day of MVPA during school (N = 172 children)

| Association with MVPA during school (minutes/day)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% CI | p | |

| Intercept | 35.0 | 27.9, 41.3 | - |

| PE teacher | 5.8 | −0.9, 12.6 | .089 |

| ≥ 100 minutes/week of PE | 6.7 | 0.1, 13.4 | .049 |

| ≤ 30 students/class in PE | 1.7 | −4.0, 7.3 | .562 |

| Training on MVPA in PE | −2.5 | −7.2, 2.2 | .297 |

| Recess supervised by non-classroom teacher | 4.4 | −1.6, 10.4 | .146 |

| ≥ 20 minutes/period of recess | 2.8 | −1.9, 7.6 | .235 |

| ≤ 75 students/supervisor in recess | −6.4 | −12.2, −0.6 | .031 |

| Activities provided during recess | 1.4 | −3.2, 6.1 | .546 |

| Training on MVPA in classroom | 0.6 | −6.5, 7.7 | .866 |

| Implementation of MVPA in classroom | −2.5 | −6.9, 1.8 | .247 |

Note: All independent variables were yes/no items where yes = 0.5 and no = −0.5; model controlled for children’s age and gender, city, study, intervention condition, accelerometer model, and whether school informant was employed at school during the year of accelerometer data collection

Abbreviations: MVPA = moderate to vigorous physical activity; PE = physical education; B = unstandardized coefficient (interpreted as minutes/day of MVPA); CI = confidence interval

Data from San Diego, CA and Seattle, WA USA, 2009–2010

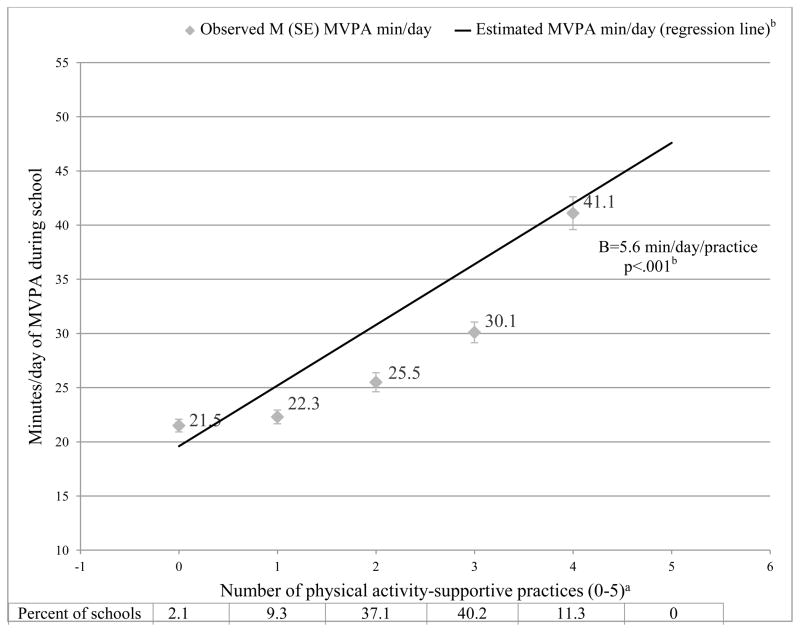

The school physical activity practices index comprised 5 practices: having a PE teacher, providing ≥ 100 minutes/week of PE, having recess supervised by a non-classroom teacher, providing ≥ 20 minutes/period of recess, and having ≥ 75 students/supervisor in recess (the last variable was reverse coded compared to model 1 because of its negative association with MVPA). The index was positively associated with children’s minutes/day of MVPA during school, with each additional practice accounting for 5.6 more minutes/day of MVPA during school (p < .001; see Figure 1). Plots of the unadjusted sample means showed that children at schools with 0 or 1 of the 5 practices (11.4% of schools) had an average of 22.2 (SD = 7.8) minutes/day of MVPA during school, while children at schools with 4 of the 5 practices (11.3% of schools) had an average of 41.1 (SD = 19.8) minutes/day of MVPA during school.

Figure 1.

Relationship between number of physical activity practices from the indexa and children’s objectively measured minutes/day of MVPA during school (N = 172 children)

Note: aThe 5 physical activity practices were having a PE teacher, providing ≥ 100 minutes/week of PE, having recess supervised by non-classroom teacher, providing ≥ 20 minutes/period of recess, and having ≥ 75 students/supervisor in recess; bFrom mixed effects regression model controlling for children’s age and gender, city, study, intervention condition, accelerometer model, and whether school informant was employed at school during the year of accelerometer data collection

Abbreviations: M = mean; SE = standard error of mean; min = minutes; MVPA = moderate to vigorous physical activity

Data from San Diego, CA and Seattle, WA USA, 2009–2010

DISCUSSION

Children’s objectively measured physical activity at school varied substantially, with the top 10% of schools providing 20 more minutes/day of MVPA than the bottom 10% of schools. Only 45% of children met guidelines of ≥ 30 minutes/day of MVPA during school (CDC 2011, Koplan et al. 2005, Pate et al. 2006) and > 15% of students having < 15 minutes/day of MVPA during school. Whether the school had a PE teacher, provided ≥ 100 minutes/week of PE, and had ≥ 75 students/supervisor in recess explained a significant amount of this variation in physical activity during school. Children at schools that had 4 of the 5 top practices obtained twice as many minutes/day of physical activity during school than children at schools that had only 0 or 1 of the 5 practices, thus supporting the study hypothesis. The association between the school practices index and children’s physical activity suggests that schools need to adopt multiple physical activity-supportive practices. However, having a PE teacher and providing ≥ 100 minutes/week of PE stood out as important single practices, consistent with a recent review (Bassett et al., 2013). Although the p value for the association between having a PE teacher and children’s MVPA was 0.089 and not <0.05, the coefficient of 5.8 minutes/day has clinical significance and the lack of statistical significance may have been due to limited power.

Fewer than 20% of schools reported PE that totaled ≥ 100 minutes/week, which suggests that most were not meeting their state’s mandate of 100 minutes/week (California State Board of Education 1999, National Cancer Institute 2011), and <10% were meeting the recommended 150 minutes/week (CDC 2011, Koplan et al. 2005; Pate et al. 2006). Time allocated for PE in the present study was slightly lower than what was reported in a national study from 2007–2008 (Turner et al. 2010). Thus, the amount of PE should be a primary target for intervention, but quality of PE should not be discounted. Schools that had a PE teacher were less likely to meet the 100 minutes/week mandate than schools where PE was implemented by classroom teachers. It is possible that principals, who served as informants in schools without a PE teacher, overestimated the amount of PE provided in their school because they were unaware or more subject to response bias. Thus, direct observation may be needed to more accurately measure school practices. It is also likely that a single PE teacher does not have enough time to provide 100 minutes/week of PE to all children in a school. In these circumstances, classroom teachers could be trained to supplement PE to meet the mandate.

It was unexpected that children at schools with a larger student-to-teacher ratio in recess had more physical activity than children at schools with a smaller student-to-teacher ratio. It is possible that recess periods with more children had more options for physical activity in groups or more space for physical activity. It is also possible that supervisors suppress physical activity, particularly when trained to attend to safety. Studies of parks have found that children were less physically active when supervised closely by a parent or adult (Floyd et al. 2011). Studies on class size have found that children were typically less active in larger vs. smaller PE lessons (McKenzie et al. 2001, UCLA et al. 2007), but recess period size has been less studied. Having someone other than a classroom teacher supervise recess had a positive, albeit nonsignificant, relationship with children’s physical activity during school in the present study. These findings suggest that hiring staff or seeking volunteers and training them to support physical activity during recess could lead to increases in children’s physical activity during recess.

It was unexpected that training on MVPA in PE was not associated with children’s MVPA during school or with training on MVPA in the classroom. The latter finding suggests that when teachers are trained to support MVPA, the training is focused on either PE or classroom time, not both. Efficiency and reach would likely be improved if teachers were trained to support MVPA in multiple settings. The finding that almost 55% of schools had classroom teachers who were implementing physical activity in the classroom seems promising. However, this practice was not related to children’s physical activity during school, suggesting that schools may need to improve training and reporting of classroom physical activity (Donnelly et al. 2009, Mahar et al. 2006). It is likely that the survey respondent was not aware of the frequency of implementing physical activity in any given classroom.

Strengths/Limitations

The time discrepancy between the accelerometer data collection and the school practices survey may have contributed to measurement error due to recall difficulty. However, 83% of respondents were employed at the same school during both assessment periods. There could have been differences in school practices between grades, and since the survey referenced 5th grade, this could have also led to measurement error. The refusal of 3 large districts in San Diego limits generalizability because of potential participation bias. The school practice index based on the present sample may not be generalizable, and the small number of children per school assessed means that the physical activity data collected may not be representative of other children in the school. However, 97 schools is a substantial number compared to other studies (Donnelly et al. 2009, Mahar et al. 2006, McKenzie et al. 1996, Sallis et al. 1997). It is possible the 30-second accelerometer epoch length underestimated children’s MVPA as compared to a shorter epoch length (Baquet et al 2007). A strength of this study is that it is among the few that have compared objective physical activity data to indicators of school practice and policy. It is important to note that physical activity-supportive school practices may co-occur with physically active children (e.g., in active communities), rather than cause children to be more physically active. Future studies should aim to recruit ≥ 10 randomly selected children per school from a large number of schools (e.g., 100) and employ objective measures of school practices to avoid response bias. Intervention studies are needed to identify effects of implementing new physical activity practices in schools.

Conclusions

Elementary schools vary widely in the number of physical activity practices implemented. A key implication is that schools should implement multiple evidence-based strategies for providing physical activity opportunities, and more than 10% of schools were implementing most of the effective practices. Practices related to having a PE teacher, providing ≥ 100 minutes/week of PE, and training staff or volunteers to supervise recess stood out as being most important. Implementing these physical activity practices could reach large numbers of children every day. More support, monitoring, and accountability of school physical activity opportunities may be needed to improve children’s physical activity.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Children’s physical activity during school varied drastically across schools.

School practices were positively related to children’s objectively measured physical activity.

Multiple physical activity practices were more important than any single practice.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was from NIH ES014240, NIH DK072994, and The California Endowment

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jordan A. Carlson, Email: jacarlson@ucsd.edu.

James F. Sallis, Email: jsallis@ucsd.edu.

Gregory J. Norman, Email: gnorman@ucsd.edu.

Thomas L. McKenzie, Email: tmckenzi@mail.sdsu.edu.

Jacqueline Kerr, Email: jkerr@ucsd.edu.

Elva M. Arredondo, Email: earredondo@projects.sdsu.edu.

Hala Madanat, Email: hmadanat@mail.sdsu.edu.

Alexandra M. Mignano, Email: amignano@ucsd.edu.

Kelli L. Cain, Email: kcain@ucsd.edu.

John P. Elder, Email: jelder@mail.sdsu.edu.

Brian E. Saelens, Email: brian.saelens@seattlechildrens.org.

References

- Baquet G, Stratton G, Van Praagh E, Berthoin S. Improving physical activity assessment in prepubertal children with high-frequency accelerometer monitoring: a methodological issue. Prev Med. 2007;44:143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett DR, Fitzhugh EC, Heath GW, Erwin PC, Frederick GM, Wolff DL, Welch WA, Stout AB. Estimated energy expenditures for school-based policies and active living. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Education. Data & statistics. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.cde.ca.gov/ds/

- California State Board of Education. Policy #99-03. 1999 Retrieved from http://www.cde.ca.gov/be/ms/po/policy99-03-June1999.asp.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. School health guidelines to promote healthy eating and physical activity. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly JE, Greene JL, Gibson CA, Smith BK, Washburn RA, Sullivan DK, DuBose K, Mayo MS, Schmelzle KH, Ryan JJ, Jacobsen DJ, Williams SL. Physical Activity Across the Curriculum (PAAC): a randomized controlled trial to promote physical activity and diminish overweight and obesity in elementary school children. Prev Med. 2009;49:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder JP, Crespo NC, Corder K, Ayala GX, Slymen DJ, Lopez NV, Moody JS, McKenzie TL. Childhood obesity prevention and control in city recreation centers and family homes: the MOVE/me Muevo Project. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd MF, Bocarro JN, Smith WR, Baran PK, Moore RC, Cosco NG, Edwards MB, Suau LJ, Fang K. Park-based physical activity among children and adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedson P, Pober D, Janz K. Calibration of accelerometer output for children. Med Sci Sports Exercise. 2005;37:S523–S530. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185658.28284.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz KF. Validation of the CSA accelerometer for assessing children’s physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exercise. 1994;26:369–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koplan J, Liverman CT, Kraak VI. Preventing childhood obesity: health in the balance. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SM, Burgeson CR, Fulton JE, Spain CG. Physical education and physical activity results from the School Health Policies and Programs Study 2006. J Sch Health. 2007;77:435–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lounsbery MAF, McKenzie TL, Morrow JR, Holt KA, Budnar RG. School Physical Activity Policy Assessment. J Phys Act Health. 2012 doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.4.496. online first. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahar MT, Murphy SK, Rowe DA, Golden J, Shields AT, Raedeke TD. Effects of a classroom-based program on physical activity and on-task behavior. Med Sci Sports Exercise. 2006;38:2086–2094. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000235359.16685.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie TL, Nader PR, Strikmiller PK, Yang M, Stone EJ, Perry CL, Taylor WC, Epping JN, Feldman HA, Luepker RV, Kelder SH. School physical education: effect of the Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health. Prev Med. 1996;25:426–431. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie TL, Stone EJ, Feldman HA, Epping JN, Yang M, Strikmiller PK, Lytle LA, Parcel GS. Effects of the CATCH physical education intervention: teacher type and lesson location. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:101–109. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00335-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association for Sport and Physical Education. Physical education guidelines. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.aahperd.org/naspe/standards/nationalGuidelines/PEguidelines.cfm.

- National Cancer Institute. Classification of laws associated with school students. 2011 Retrieved from http://class.cancer.gov/

- Pate RR, Davis MG, Robinson TN, Stone EJ, McKenzie TL, Young JC. Promoting physical activity in children and youth: a leadership role for schools: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism (Physical Activity Committee) in collaboration with the Councils on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young and Cardiovascular Nursing. Circulation. 2006;114:1214–1224. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.177052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Frank LD, Couch SC, Zhou C, Colburn T, Cain KL, Chapman J, Glanz K. Obesogenic neighborhood environments, child and parent obesity: the Neighborhood Impact on Kids Study. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Conway TL, Prochaska JJ, McKenzie TL, Marshall SJ, Brown M. The association of school environments with youth physical activity. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:618–620. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.4.618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, McKenzie TL, Alcaraz JE, Kolody B, Faucette N, Hovell MF. The effects of a 2-year physical education program (SPARK) on physical activity and fitness in elementary school students. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1328–1334. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.8.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Uijtdewilligen L, Twisk JWR, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJM. Physical activity and performance at school: a systematic review of the literature including a methodological quality assessment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:49–55. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- State of Washington, Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.k12.wa.us/DataAdmin/default.aspx#download.

- Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exercise. 2008;40:181–188. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner L, Chaloupka FJ, Chriqui JF, Sandoval A. School policies and practices to improve health and prevent obesity: national elementary school survey results: school years 2006–07 and 2007–08. Vol. 1. Chicago, IL: Bridging the Gap Program, Health Policy Center, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago; 2010. Retrieved from http://www.bridgingthegapresearch.org. [Google Scholar]

- UCLA Center to Eliminate Health Disparities, Samuels & Associates, the Active Living Research Program. Failing fitness: physical activity and physical education in schools. Los Angeles, CA: The California Endowment; 2007. Retrieved from: http://www.calendow.org/uploadedFiles/failing_fitness.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical activity guidelines for Americans. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/pdf/paguide.pdf.

- Welk GJ, Corbin CB, Dale D. Measurement issues in the assessment of physical activity in children. Res Q Exercise Sport. 2007;71:S59–S73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]