Abstract

Background

Noroviruses (NoVs) are the most common cause of epidemic gastroenteritis, responsible for at least 50% of all gastroenteritis outbreaks worldwide and were recently identified as a leading cause of travelers’ diarrhea (TD) in U.S. and European travelers to Mexico, Guatemala and India.

Methods

Serum and diarrheic stool samples were collected from 75 US student travelers to Cuernavaca, Mexico, who developed TD. NoV RNA was detected in acute diarrheic stool samples using RT-PCR. Serology assays were performed using GI.1 Norwalk virus (NV) and GII.4 Houston virus (HOV) virus-like particles (VLP) to measure serum levels of IgA and IgG by Dissociation-Enhanced Lanthanide Fluorescent Immunoassay (DELFIA); serum IgM was measured by capture ELISA, and the 50% antibody blocking titer (BT50) was determined by a carbohydrate-blocking assay.

Results

NoV infection was identified in 12 (16%; 9 GI-NoV and 3 GII-NoV) of 75 travelers by either RT-PCR or ≥4-fold rise in antibody titer. Significantly more individuals had detectable pre-existing IgA antibodies against HOV (62/75, 83%) than against NV (49/75, 65%) (p=0.025) VLPs. A significant difference was observed between NV- and HOV-specific preexisting IgA antibody levels (p=0.0037), IgG (p=0.003) and BT50 (p=<0.0001). None of the NoV-infected TD travelers had BT50 >200, a level that has been described previously as a possible correlate of protection.

Conclusions

We found that GI-NoVs are commonly associated with TD cases identified in U.S. adults traveling to Mexico, and seroprevalence rates and geometric mean antibody levels to a GI-NoV were lower than to a GII-NoV strain.

Noroviruses (NoVs) are the most common cause of epidemic gastroenteritis, responsible for at least 50% of all gastroenteritis outbreaks worldwide, and a major cause of foodborne illness 1 NoVs are a diverse group of viruses in the family Caliciviridae, and they are currently classified into 5 genogroups (GI-GV) and further subdivided into multiple genotypes 2. Strains that infect humans are found in GI, GII and GIV, with GII.4 strains notably causing over 80% of NoV infections worldwide 3. NoVs are highly infectious, very stable and remarkably transmissible 4, 5. Besides being a leading cause of epidemic acute gastroenteritis and an important cause of hospital acquired and sporadic infection, NoVs have also been described as a common etiology of travelers’ diarrhea (TD)6, 7. Interestingly, TD studies over time and in different locations have reported a marked diversity of GI- and GII-NoVs among cases 6, 8–10. However, an almost equivalent number of NoV-associated traveler’s diarrhea (NoV-TD) cases are associated with strains from both genogroups 6, which contrasts with the predominance of GII.4 viruses being associated with outbreak settings and sporadic cases worldwide 11, 12.

The role of the antibodies elicited after a NoV infection, particularly those of specific antibody classes, has been difficult to discern since in some studies individuals with high pre-challenge ELISA titers were more likely to become infected than individuals with low pre-existing titers13, 14. More recently, the presence of antibodies that block the binding of NoV virus-like particles (VLPs) to histo-blood group antigens (HBGAs) prior to challenge or inhibit VLP binding to red blood cells have correlated with protection against clinical NoV gastroenteritis 15–17.

The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of NoV genogroup-specific antibodies in a group of U.S. travelers to Mexico and the occurrence of natural NoV infection during travel. Recombinant GI (Norwalk virus [NV]) and GII (Houston virus [HOV]) VLPs were used to determine the role of pre-existing serum antibodies (IgA, IgG, IgM and HBGA blocking antibodies) in protection from NoV-TD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

U.S. student travelers (≥18 years of age) to schools in Cuernavaca, Mexico during the summer of 2004, were invited participate in a prospective study for the assessment of the etiology of TD and correlates of protection against the disease. Due to the initial design of the study, only those travelers presenting TD symptoms provided stool specimens when ill. TD was defined as the passage of ≥3 unformed stools within a 24-hour period associated with ≥1 of the following symptoms: abdominal pain or cramps, flatulence, nausea, vomiting, fever (temperature, ≥100°F [≥37.8°C]), blood and/or mucus in the stool, or tenesmus. Exclusion criteria involved having other clinically important underlying illness, diarrhea for ≥72 hours, on current treatment against diarrheal pathogens, being pregnant and breast-feeding.

A blood sample was drawn from all study participants ≤48 hours of arrival in Mexico (referred to as pre-existing) and at another time point ≤48 hours prior to departure (referred to as pre-departure). During the course of stay in Mexico, a stool sample was obtained within 48 hours of onset of diarrhea. All samples were submitted to the laboratory at the Center of Infectious Diseases, University of Texas School of Public Health in Houston, Texas for analysis. Stool samples were screened for common enteric bacterial and parasitic pathogens using previously published methods 18. Where sufficient stool was available, the samples were tested for NoV using methods previously reported 6.

Definition of NoV-TD

A case was considered to be NoV-TD if the clinical description matched the definition of TD and NoV was detected in the stool sample by PCR and/or there was a ≥4-fold increase in antibody titer (HBGA blocking antibodies) or concentration (IgA and IgG) between pre-existing and pre-departure serum samples using any of the serological assays described below.

Detection and characterization of NoVs

Detection of NoVs was performed as described previously 6. Briefly, viral RNA was extracted from 200 μL of a 10% stool suspension (in 0.01 mol/L phosphate-buffered saline) with a QIAamp viral RNA kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the RNA was stored at −80°C until used. The reverse transcription (RT) reaction was carried out in 50 μL of a reaction mixture containing 75 pmol of random hexamers (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 5 U of AMV-RT (Life Sciences), 1X AMV-RT buffer (Life Sciences), 10 mmol/L of dNTP mix, 10 U of Protector RNase Inhibitor (Promega), and 10 μL of RNA extract. The reaction was performed for 2 h at 43°C, and the enzyme was inactivated at 75°C for 5 min. The resulting cDNA was stored at −20°C until used in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays. A set of degenerate primers 19 was used for initial detection of NoVs and a genogrouping PCR assay was performed on positive samples using primers G1SKF, G1SKR, G2SKF, and G2SKR 20. All PCR products were separated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized under UV lamp after ethidium bromide staining. Pathogens other than NoVs were previously sought in this population and reported elsewhere 21.

Serology assays

Anti-norovirus IgA and IgG were determined by DELFIA (Dissociation-Enhanced Lanthanide Fluorescent Immunoassay) and IgM by a capture ELISA as described elsewhere 22, with an adaptation to include detection of specific antibodies against HOV-VLPs as well as against NV-VLPs. For serum IgA and IgG detection, immunoglobulin concentrations (μg/ml) were calculated by interpolation from standard curves generated using purified IgG or IgA. For the serum IgM assay, a test sample was considered positive if the optical density (OD) value was above the average of blanks plus three-times the standard deviation of all the blanks. The blocking assay was carried out as described previously 17, and was also adapted for testing HOV-VLPs using H type 1 synthetic carbohydrate. The 50% blocking titer (BT50) was, defined as the titer at which the OD reading (after subtraction of the blank) was 50% of the OD of the positive control. A value of 12.5 was assigned to samples with BT50 below the limit of detection of the assay (<25).

Statistical Analyses

Wilcoxon signed rank test was used for the comparison of paired nonparametric data. McNemar’s test was used to compare the proportion of NV and HOV-IgA and IgG positive travelers.

RESULTS

Study population and sample collection

The study population consisted of 75 U.S. students (age: 18–76 years, mean: 26 years; median: 22 years), of whom 86% were Caucasian, 84% of non-Hispanic ethnicity and 54% were female. The average length of stay in Cuernavaca was 32 days (median: 37 days, range: 12–53 days). Paired (pre-existing and pre-departure) serum samples were collected from 75 travelers who experienced TD. Of these, diarrheal stool samples were collected from 56 travelers for enteropathogen studies. After initial testing for bacteria and parasites, sufficient stool was available from 37 subjects for screening for NoV. Of the travelers who provided both blood samples along with a stool sample, the average time between the onset of symptoms and the pre-departure blood draw was 16 days (median: 13 days; range: 1–45 days).

Prevalence of NoV among TD patients

Ten of the 37 stool samples (27%) tested positive for NoV by RT-PCR. Of these, 7 samples (70%) were identified as GI-NoVs, and 3 (30%) were identified as GII-NoVs. Additionally, 2 travelers, from whom stools samples were not available for NoV detection, were diagnosed as cases of GI-NoV-TD based on a ≥4-fold increase in serum antibody titers (>15-fold increase NV-IgA, and >4-fold increase in NV-IgG for both travelers). Overall, 12 (16%) of the 75 travelers were determined as having NoV-TD. Only one individual for which a stool sample was available and NoV was detected (GI-NoV) had a ≥4-fold increase in serum antibody titers. Among NoV-positive travelers, the average duration between onset of symptoms and the pre-departure blood sample draw was 22 days (median: 23 days, range: 10–36 days).

Pre-existing IgA

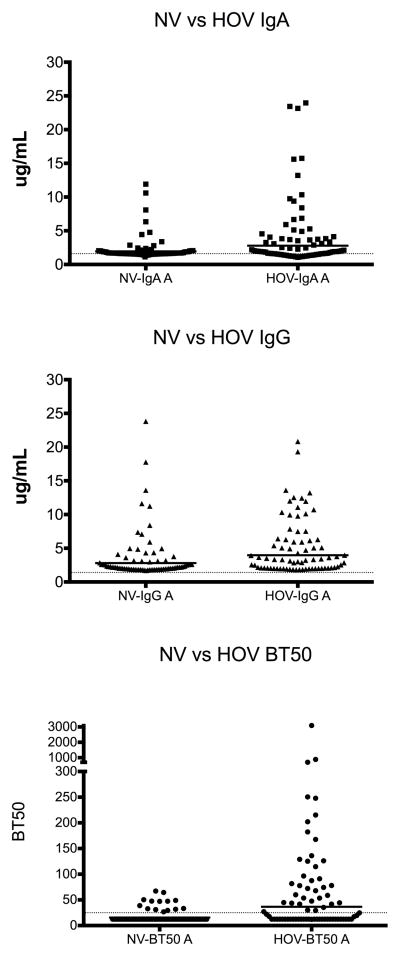

Among pre-existing serum samples, 49/75 (65%) of samples were found to have measurable levels of NV-IgA (≥ 1.6 μg/mL), whereas significantly more individuals (62/75, 83%) had HOV specific IgA (p=0.025) (Figure 1). The median concentration of pre-existing serum IgA against NV-VLPs for was of 1.67 μg/mL (range: 1.13–11.91 μg/mL), and was also significantly lower than the median concentration against HOV, which was 2.04 μg/mL (range: 1.06–23.97) (p=0.0037).

Figure 1.

Comparison between pre-existing serum antibody levels against Norwalk virus (NV) virus like particle (VLP) and Houston virus (HOV) VLP. A. Anti-NV and –HOV IgA levels, p=0.0037; Wilcoxon signed rank test, cutoff: 1.4μg/mL. B. Anti-NV and –HOV IgG levels p=0.003; Wilcoxon signed rank test, cutoff: 1.6μg/mL. C; BT50 values of NV- and HOV-blocking antibodies, p=<0.0001; Wilcoxon signed rank test). Bars represent geometric means and dotted lines the cutoff value.

However, the level of pre-existing IgA antibodies against NV or HOV did not correlate with protection against GI- or GII-NoV infection (Table 1). The frequency of development of GI-NoV diarrhea was similar among NV-IgA seropositive (12.2%) and seronegative (11.5%) individuals. Similar results were observed for HOV specific IgA where all the 3 individuals infected with GII-NoVs had detectable levels of HOV specific IgA.

Table 1.

Distribution of total (N) and NoV-TD travelers by pre-existing levels of IgA, IgG and BT50, titers against NV- and HOV-VLPs.

| NV-IgA | NV-IgG | NV-BT50* | HOV-IgA | HOV-IgG | HOV-BT50*, ** | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1.6 μg/mL | >1.6 μg/mL | <1.4 μg/mL | >1.4 μg/mL | <25 | >25 | <1.6 μg/mL | >1.6 μg/mL | <1.4 μg/mL | >1.4 μg/mL | <25 | >25 | |

| N=75 | 26 (35) | 49 (65) | 0 | 75 (100) | 61 (89) | 14 (11) | 23 (31) | 52 (69) | 0 | 75 (100) | 36 (49) | 37 (51) |

| NoV-TD | 4 (33) | 8 (67) | 0 | 12 (100) | 10 (83) | 2 (17) | 1 (8) | 11 (92) | 0 | 12 | 5 (50) | 5 (50) |

| GI-NoV | 3 | 6 | 0 | 9 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 9 | 3 | 4 |

| GII-NoV | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

For BT50, travelers are classified having titers above or below 25 (<25, seronegative; >25, seropositive), and for IgA and IgG are classified by seropositivity. The number in parenthesis indicates the percentage of NV-TD travelers in the specific group

Two GI-NoV positive samples not included due to lack of sera.

Pre-existing IgG

All the samples tested had measurable levels of IgG against NV and HOV-VLPs (Table 1). The median concentration of antibodies against NV-VLPs in pre-existing serum samples was 2.19 μg/mL (range: 1.70–23.82 μg/mL), and that against HOV-VLPs was 3.33 μg/mL (range: 1.81–20.83 μg/mL). Overall, travelers had higher preexisting concentration of serum IgG against HOV-VLPs than to NV-VLPs (p=0.003) (Figure 1). However, the presence of preexisting antibodies did not correlate with protection against GI- or GII-NoV infection.

IgM

Pre-existing levels of IgM was detected in one serum sample using NV-VLPs. This individual had neither detectable NoV in stool nor an increase in IgA or IgG antibody titer. The pre-departure serum sample of this individual remained positive for IgM anti NV-VLP. None of the serum samples tested with HOV-VLPs had detectable levels of serum IgM (data not shown).

HBGA blocking antibodies

Of the 75 serum samples collected upon enrollment that were tested for H-type 1 blocking antibodies, only 14 (19%) had BT50 >25 against NV-VLP compared to 37 (51%) against HOV (p<0.0001). The median BT50 against NV was 12.5 (range: 12.5–67.2) compared to 27.1 (range: 12.5–3091.7) for HOV (p=<0.0001).

There was no difference between pre-existing BT50 of infected and non-infected travelers for NV infection (infected: median NV-BT50 12.5 [range: 12.5–32.80]; uninfected: median NV-BT50 12.5 [range: 12.5–67.20], p=0.714) (Table 1). None of the travelers with NoV-TD had BT50 >200, suggesting that the overall seroprevalence of the putatively protecting antibody levels was low among this group.

NoV single infection and NoV coinfections

Of the NoV positive travelers, the presence of co-pathogens was observed in 9 (75%) of samples. The most common co-pathogen found was enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC), which was present in 7 (58%) of NoV-positive samples.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of NoV-associated TD found in this study was 16%, similar to what has been reported previously for comparable populations traveling to Mexico (circa 15%) 6, 9, 10. However, this result is an underestimate of the prevalence of NoV-TD in international travelers since we only studied diarrhea and not gastroenteritis with vomiting, a much more common presentation of illness caused by this group of viruses, and only half of the stool samples collected were available for testing. Similar to previous reports, GI-associated NoV-TD cases were more prevalent (75%) than GII-NoVs 8, 9. This result supports previous studies confirming that NoVs are a commonly identified pathogen of TD in U.S. travelers to Mexico.

To detect baseline levels of antibodies against NoVs among travelers we chose to use VLPs from two different strains of NoV-VLPs (GI.1-NV and GII.4-HOV) that represents the predominant genotype within genogroups I and II, respectively. In this context, a significantly greater number of travelers had pre-existing IgA antibodies to HOV-VLPs than to NV-VLPs (p=0.025) and in higher titers (p=0.0037). The higher seroprevalence rates for GII.4 may be due to the predominance of these strains worldwide3. Although a confirmed history of previous NoV infection was not available for any of the study participants, serum samples from all study participants had IgG levels against NV- and HOV-VLPs above the assay cut-off, suggesting at least one previous exposure to the virus. The presence of pre-existing antibodies against NoVs was not associated with protection specifically from GI or GII NoVs; however, the small number of test samples and the lack of testing of travelers who did not experience TD limit this conclusion. Nonetheless, previous studies have demonstrated that a prior NoV infection does not confer long-term homologous protection against subsequent infections and disease 13, 14.

Previous results from our laboratory and others suggest that antibodies capable of inhibiting the binding of VLPs to HBGAs or red blood cells have correlated with protection against disease 15–17, 23. The frequency and the level of blocking antibodies found among travelers against HOV-VLP were higher than that against NV-VLP (p=<0.0001), in agreement with the serum IgA and IgG results. Of the 12 travelers infected with NoVs, 9 were considered seronegative for blocking antibodies (BT50 <25) and three others had titers below the suggested threshold for protection against infection and viral illness (BT50 <200) 23. Future comprehensive studies are needed to confirm cross-reactivity of protection conferred by blocking antibodies.

Only three of 12 infected individuals had a ≥4-fold rise in antibody titers following infection (data not shown). However, this difference was not attributed to the length of time between samples for both groups since individuals who showed a ≥4-fold rise in antibody titers following infection had an average of 33 days between sample collection, similarly to that of 29 days for individuals who did not have a significant sero-response. Nevertheless, these results could underestimate the antibody response in this population since the serological assays were carried out with VLPs representative of GI and GII viruses that may not have been homologous to the virus detected in stool, thus decreasing the sensitivity of the assay. For future studies, homologous VLPS for determining sero-responses to NoV infection should be used due to the high capsid sequence diversity observed in this group of viruses. Nonetheless, the DELFIA assay used in this study has previously been shown to be highly specific when compared to antigen detection in stool (Kavanagh et al CVI 2011). The small quantity of stool samples was a limiting factor in carrying out genotyping assays in this study.

A high level of co-infections was observed among travelers with NoV-TD. This observation is in line with our previous studies in travelers where rates of co-infections are found to be over 60% 7. TD is characterized as multifactorial disease caused by a wide range of enteric pathogens including bacteria, viruses and parasites 24. Furthermore, the ratio of pathogen co-infection in ill travelers is significant among the total number of cases. Other pathogens in addition to viruses must be sought for when defining the etiology of TD. However, it should be noted that the presence of co-pathogens did not appear to interfere with the stimulation of the immune response to NoVs since the travelers who showed a ≥4-fold rise in antibody had multiple enteric pathogens detected in their stools.

In conclusion, we provide more evidence that NoVs are associated with the development of TD among US travelers to Mexico. Moreover, not only fewer travelers have antibodies against a GI-VLP compared to a GII-VLP, but also the amount of specific antibodies detected was lower for a GI-VLP than a GII-VLP. These results could partially explain the continuous presence of GI-NoV infections in travelers to these locations 8, 9. Altogether, international travelers to developing regions of the world represent a unique and traceable population with relatively low prevalence of blocking antibodies and high rates of NoV endemicity, making them valuable for evaluation of NoV vaccines in the pipeline for development 25.

Acknowledgments

Research sponsorship was the following: NIH (PO1-AI057788; P30-DK56338) and USDA (2011-68003.30395)

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

R.L.A. has received research support from Takeda Vaccines (Montana), Inc. M.K.E. received support from NIH7NIAID to conduct the study. She is an inventor on patents related to cloning of the Norwark virus genome and is a consultant to Takeda Vaccines (Montana), Inc.

The other authors state they have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.NCfI Division of Viral Diseases, CfDC Respiratory Diseases, Prevention. Updated norovirus outbreak management and disease prevention guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(RR-3):1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng DP, Ando T, Fankhauser RL, et al. Norovirus classification and proposed strain nomenclature. Virology. 2006;346(2):312–23. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glass RI, Parashar UD, Estes MK. Norovirus gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(18):1776–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seitz SR, Leon JS, Schwab KJ, et al. Norovirus infectivity in humans and persistence in water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(19):6884–8. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05806-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wikswo ME, Hall AJ. Outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis transmitted by person-to-person contact - united states, 2009–2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012;61(9):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ajami N, Koo H, Darkoh C, et al. Characterization of norovirus-associated traveler’s diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(2):123–30. doi: 10.1086/653530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koo HL, Ajami NJ, Jiang ZD, et al. Noroviruses as a cause of diarrhea in travelers to guatemala, india, and mexico. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(5):1673–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02072-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapin AR, Carpenter CM, Dudley WC, et al. Prevalence of norovirus among visitors from the united states to mexico and guatemala who experience traveler’s diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(3):1112–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.3.1112-1117.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ko G, Jiang ZD, Okhuysen PC, DuPont HL. Fecal cytokines and markers of intestinal inflammation in international travelers with diarrhea due to noroviruses. J Med Virol. 2006;78(6):825–8. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koo HL, Ajami N, Atmar RL, DuPont HL. Noroviruses: The leading cause of gastroenteritis worldwide. Discov Med. 2010;10(50):61–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindesmith LC, Donaldson EF, Lobue AD, et al. Mechanisms of gii.4 norovirus persistence in human populations. PLoS Med. 2008;5(2):e31. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noel JS, Fankhauser RL, Ando T, et al. Identification of a distinct common strain of “norwalk-like viruses” having a global distribution. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(6):1334–44. doi: 10.1086/314783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson PC, Mathewson JJ, DuPont HL, Greenberg HB. Multiple-challenge study of host susceptibility to norwalk gastroenteritis in us adults. J Infect Dis. 1990;161(1):18–21. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parrino TA, Schreiber DS, Trier JS, et al. Clinical immunity in acute gastroenteritis caused by norwalk agent. N Engl J Med. 1977;297(2):86–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197707142970204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Czako R, Atmar RL, Opekun AR, et al. Serum hemagglutination inhibition activity correlates with protection from gastroenteritis in persons infected with norwalk virus. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012;19(2):284–7. doi: 10.1128/CVI.05592-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nurminen K, Blazevic V, Huhti L, et al. Prevalence of norovirus gii-4 antibodies in finnish children. J Med Virol. 2011;83(3):525–31. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reeck A, Kavanagh O, Estes MK, et al. Serological correlate of protection against norovirus-induced gastroenteritis. J Infect Dis. 2011;202(8):1212–8. doi: 10.1086/656364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang ZD, Lowe B, Verenkar MP, et al. Prevalence of enteric pathogens among international travelers with diarrhea acquired in kenya (mombasa), india (goa), or jamaica (montego bay) J Infect Dis. 2002;185(4):497–502. doi: 10.1086/338834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson AD, Garrett VD, Sobel J, et al. Multistate outbreak of norwalk-like virus gastroenteritis associated with a common caterer. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(11):1013–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.11.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kojima S, Kageyama T, Fukushi S, et al. Genogroup-specific pcr primers for detection of norwalk-like viruses. J Virol Methods. 2002;100(1–2):107–14. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(01)00404-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dupont HL, Jiang ZD, Belkind-Gerson J, et al. Treatment of travelers’ diarrhea: Randomized trial comparing rifaximin, rifaximin plus loperamide, and loperamide alone. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2007;5(4):451–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kavanagh O, Estes MK, Reeck A, et al. Serological responses to experimental norwalk virus infection measured using a quantitative duplex time-resolved fluorescence immunoassay. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18(7):1187–90. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00039-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atmar RL, Bernstein DI, Harro CD, et al. Norovirus vaccine against experimental human norwalk virus illness. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2178–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1101245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shah N, DuPont HL, Ramsey DJ. Global etiology of travelers’ diarrhea: Systematic review from 1973 to the present. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80(4):609–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atmar RL, Estes MK. Norovirus vaccine development: Next steps. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2012;11(9):1023–5. doi: 10.1586/erv.12.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]