In 1999, former U.S. Surgeon General Dr. David Satcher stated, “Through partnership with faith organizations and the use of health promotion and disease prevention sciences, we can form a mighty alliance to build strong, healthy, and productive communities.”1 This sentiment was recently seconded by Dr. Howard Koh, Assistant Secretary for Health.2 Despite the contentiousness surrounding establishment of the White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives (OFBCI) under President Bush, repurposed as the Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships (OFBNP) under President Obama, the subsequent creation of a Center for Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships (the Partnership Center) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) signifies that faith-health partnerships are no longer hypothetical; rather, they are an ongoing part of the national conversation on public health.

This brief overview summarizes the scope of existing efforts among faith-based and public health institutions and organizations to work in partnership to further the health of the population. These intersections between the faith-based and public health sectors are more diverse than many public health professionals may realize, and of greater longstanding than the past two presidential administrations.3,4

CHALLENGES

Many may recall the controversy surrounding the OFBCI, established under Executive Orders by President Bush.5,6 Less recalled is that legislation authorizing the OFBCI, known as “charitable choice,” originated during the Clinton Administration.7 While the intention of the legislation and the OFBCI was simply to enable religious organizations to provide services “on the same basis as any other nongovernmental provider”7—no provision authorized federal funding for any program—and while supported by both Democrats and Republicans, these details got lost in the uproar. Concern was voiced, early on, that the OFBCI was an effort by the religious right to create a mechanism to access federal funds. In truth, much of the religious right was opposed to the OFBCI and lobbied to eliminate it.8

Over time, with a new director, lower profile, and track record of success, public glare faded and the OFBCI became an accepted part of the White House infrastructure. It was retained by President Obama,9 with an advisory board containing national leaders known for progressive viewpoints. While at one time there were concerns about how the federal faith-based concept would play out, when it comes to public health initiatives, at least, the track record appears clean. Early concerns were overstated, but, to be fair, not all were due to fear mongering; the history of organized religion's forays into the public square are not entirely innocent. However, with legal and constitutional boundaries surrounding what is and is not permissible well vetted,10 the Obama Administration and HHS recognize this model as a means to strengthen the nation's public health efforts.

More importantly, no matter how the OFBNP has evolved, two things are apparent: (1) faith-health partnerships are not new, and (2) they cover considerable ground. Collaboration between the faith-based and public health sectors in the U.S. is as old as organized efforts in public health, dating to the 19th century.11 The challenge of meeting national and global population health priorities should not be overwhelmed by the challenge to forge creative partnerships between these sectors, no matter how daunting.12 Religious institutions, organizations, and professionals can be, and long have been, our allies in public health, as Dr. Satcher noted.1

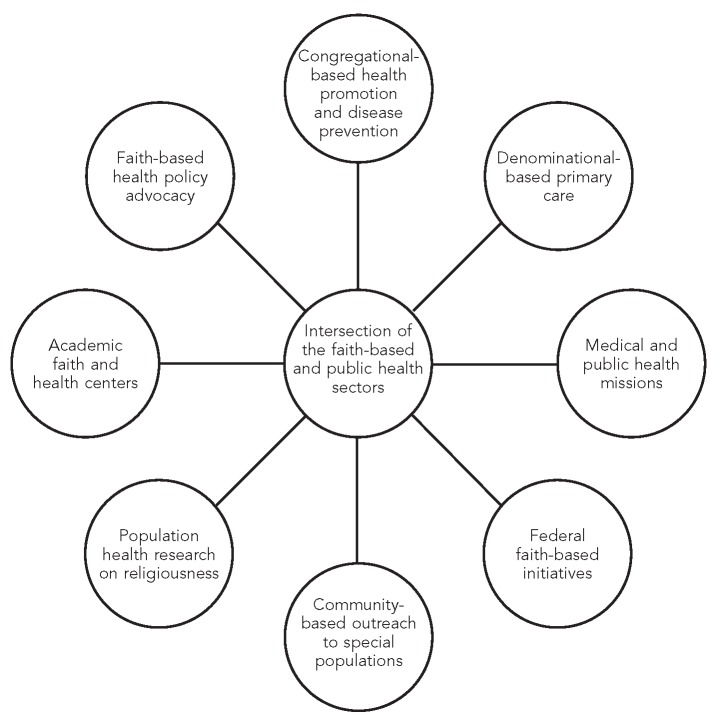

Before summarizing what is included in the Figure, what is not included is also notable; for example, groups or individuals who exploit the religious beliefs of the suffering for profit, those who espouse violence toward providers, and other unfortunate images that may come to mind at the intersection of the words “faith” and “health.” This commentary is not the place to discuss the sometimes troubled history of conflicts between people and institutions of faith and those of medicine and science. There is a different narrative to unpack that merits a wider airing: the ways that the faith-based and public health sectors continue to ally in efforts to prevent disease and promote health,13 both in the U.S. and around the world.

Figure.

Points of intersection between the faith-based and public health sectors

INITIATIVES

As shown in the Figure, the intersection of the faith-based and public health sectors contains multiple partnerships, encompassing recent initiatives and longstanding inter-sector relationships. These activities, as a whole, are representative of the fullness of what defines public health: (1) they entail public health research and education, delivery of primary care, and policy-making; (2) they target processes, impacts, and outcomes across primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of prevention; (3) they involve health educators, epidemiologists, biostatisticians, health administrators, public health nurses and preventive medicine physicians, environmental scientists, and others; and (4) they address the needs of diverse, underserved populations, especially racial/ethnic minority communities and older adults. Examples include:

Congregational-based health promotion and disease prevention: The Health and Human Services Project of the General Baptist State Convention of North Carolina, dating to the 1970s, pioneered church-based health education to underserved communities.14

Denominational-based primary care: The earliest hospitals were founded by the major faith traditions,15 seen today in the myriad Catholic, Lutheran, Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian, Adventist, Jewish, and other religiously branded medical centers.

Medical and public health missions: Christian missions providing medical and surgical care and environmental health development are most familiar, but other religions have traditions of global outreach (e.g., the Tobin Health Center serving Abayudaya Jews and their Christian and Muslim neighbors in Uganda).16

Federal faith-based initiatives: One of the highest-profile initiatives of both the OFBCI and OFBNP has been the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR),17 a centerpiece of the nation's Global Health Initiative under the Obama Administration.

Community-based outreach to special populations: Outreach encompasses many types of initiatives, from faith community (or parish) nurses18 to groups such as the Shepherd's Centers of America,19 a national network of interfaith community-based organizations serving older adults.

Population health research on religion: Thousands of studies have identified religious correlates of morbidity, mortality, and disability, including social, epidemiologic, and community-based research on physical and mental health across all major faith traditions.20

Academic faith and health centers: These centers include the Duke University Center for Spirituality, Theology, and Health;21 the University of Florida Center for Spirituality and Health;22 the George Washington Institute for Spirituality and Health;23 and the Emory University Interfaith Health Program24 and its Institute for Public Health and Faith Collaborations,25 all of which are involved in research and education.

Faith-based health policy advocacy: The recent health-care reform debate, for example, was informed by policy statements from the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops26 and from Jewish organizations across the denominational spectrum.27

This summary is, by necessity, a skeleton overview. The public health literature is replete with accounts of faith-based partnerships, especially involving health promotion and disease prevention in conjunction with local health departments.28

PROSPECTS

Can we identify ways to broaden this intersection between the faith-based and public health sectors? Two possibilities come to mind. First, the Office of the Surgeon General could use its bully pulpit to raise awareness of social-structural determinants of population health and disease, such as poverty and inaccessible preventive care.29 These issues have proven intractable for decades; solutions may require a broader effort than is possible drawing only on federal and state government resources. In a time of fiscal challenge, especially, religious organizations and institutions could serve as partners in meeting needs that are presently unmet. This promise is at the heart of the Bush and Obama Administrations' efforts to promote charitable choice through offices in the White House and cabinet-level agencies, including HHS.

Second, to advance such efforts, the U.S. Public Health Service could consider developing a companion document for Healthy People 2020 that comprehensively summarizes evidence from research and intervention studies involving collaboration with faith-based communities, organizations, or institutions for each of its 42 designated topic areas.30 Besides being a practical supplement, this document would provide, for the first time, “a complete catalog of historical and ongoing public health programs and initiatives with significant faith-based content,” as well as “a useful baseline for the development of detailed goals, objectives, and implementation plans for federal faith-based efforts” related to Healthy People.29

The faith-based sector has much to offer public health, yet it remains underused. The potential for good is considerable, but for good to come of it, the public health establishment must set aside any intrinsic misgivings (or misunderstandings) about faith-based organizations and professionals. Stereotyped portrayals of the faith-based concept and of the motives behind partnerships involving the public health sector do not map onto the longstanding history of collaborative work between religious and public health agencies and institutions. Moreover, without the involvement of the faith-based sector and other institutions of civil society, our nation will not muster the personal and tangible resources required to fully meet national31 and global32 population health goals and objectives.

But the burden is not just on those of us working in public health. The faith-based sector, too, must confront its own failings that impede such partnerships. Above all, the faith traditions must reclaim their prophetic voice regarding the health of populations. They must refocus themselves away from devotion to maintaining the status quo and toward being a force that, as Dunne said, “comforts th' afflicted [and] afflicts th' comfortable.”33 They must live up to their sacred charge to act prophetically—to call citizenry and secular governments out of their complacency and neglect, in the name of justice and mercy—to address the needs of the underserved and to promote an ethic of prevention and communitarian concern for the health and well-being of all people.

REFERENCES

- 1.Satcher D CDC/ATSDR Forum. Engaging faith communities as partners in improving community health. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), Public Health Practice Program Office; 1999. Opening address; pp. 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Transcript of the Healthy People 2020 launch. 2010. [cited 2013 Aug 8]. Available from: URL: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/connect/Transcript_Full_HP2020.pdf.

- 3.Brooks RG, Koenig HG. Crossing the secular divide: government and faith-based organizations as partners in health. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2002;32:223–34. doi: 10.2190/7A43-F5U2-7BV0-6N4V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunderson GR, Cochrane JR. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2012. Religion and the health of the public: shifting the paradigm. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bush GW. Executive Order 13198 of January 29, 2001: agency responsibilities with respect to faith-based and community initiatives. Fed Reg. 2001;66:8497–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bush GW. Executive Order 13199 of January 29, 2001: establishment of White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives. Fed Reg. 2001;66:8499–500. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke V. Comparison of proposed Charitable Choice Act of 2001 with current Charitable Choice Law. CRS report for Congress (Order Code RL31030); Washington: Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levin J, Hein JF. A faith-based prescription for the Surgeon General: challenges and recommendations. J Relig Health. 2012;51:57–91. doi: 10.1007/s10943-012-9570-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obama BH. Executive Order 13498 of February 5, 2009: amendments to Executive Order 13199 and establishment of the President's Advisory Council for Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships. Fed Reg. 2009;74:6533–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogers M, Dionne EJ., Jr . Washington: Brookings Institution; 2008. Serving people in need, safeguarding religious freedom: recommendations for the new administration on partnerships with faith-based organizations. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunderson GR. Backing onto sacred ground. Public Health Rep. 2000;115:257–61. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.2.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kegler MC, Hall SM, Kiser M. Facilitators, challenges, and collaborative activities in faith and health partnerships to address health disparities. Health Educ Behav. 2010;37:665–79. doi: 10.1177/1090198110363882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bennett RG, Hale WD. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2009. Building healthy communities through medical-religious partnerships. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatch JW, Jackson C. North Carolina Baptist Church program. Urban Health. 1981;10:70–1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Numbers RL, Amundsen DW. New York: Macmillan; 1986. Caring and curing: health and medicine in the western religious traditions. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Be'chol Lashon: In Every Tongue. Abayudaya health & development project. Tobin Health Center. [cited 2013 Aug 8]. Available from: URL: http://bechollashon.org/projects/abayudaya/projects.php#healthcare.

- 17.State Department (US) The United States President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. [cited 2013 Aug 8]. Available from: URL: http://www.pepfar.gov.

- 18.American Nurses Association. Faith community nursing: scope and standards of practice. 2nd ed. Silver Spring (MD): American Nurses Association; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shepherd's Centers of America. Living a life that matters. [cited 2013 Aug 8]. Available from: URL: http://www.shepherdcenters.org.

- 20.Koenig HG, King DE, Carson VB. Handbook of religion and health. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duke University. Center for Spirituality, Theology and Health. [cited 2013 Aug 8]. Available from: URL: http://www.spiritualityandhealth.duke.edu.

- 22.University of Florida. Center for Spirituality and Health. [cited 2013 Aug 8]. Available from: URL: http://www.ufspiritualityandhealth.org.

- 23.The George Washington University. Institute for Spirituality & Health. [cited 2013 Aug 8]. Available from: URL: http://smhs.gwu.edu/gwish.

- 24.Emory University Rollins School of Public Health. Interfaith Health Program. [cited 2013 Aug 8]. Available from: URL: http://www.interfaithhealth.emory.edu.

- 25.Kegler MC, Kiser M, Hall SM. Evaluation findings from the Institute for Public Health and Faith Collaborations. Public Health Rep. 2007;122:793–802. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Health care reform. 2011. Feb, [cited 2013 Aug 8]. Available from: URL: http://old.usccb.org/healthcare/Health%20Care%20backgrounder%202011%20final.pdf.

- 27.Levin J. Jewish ethical themes that should inform the national healthcare discussion: a prolegomenon. J Relig Health. 2012;51:589–600. doi: 10.1007/s10943-012-9617-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barnes PA, Curtis AB. A national examination of partnerships among local health departments and faith communities in the United States. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2009;15:253–63. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000349740.19361.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levin J. Engaging the faith community for public health advocacy: an agenda for the Surgeon General. J Relig Health. 2013;52:368–85. doi: 10.1007/s10943-013-9699-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Healthy People 2020: topics and objectives. [cited 2013 Aug 8]. Available from: URL: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/default.aspx.

- 31.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Healthy People 2020: framework: the vision, mission, and goals of Healthy People 2020. [cited 2013 Aug 8]. Available from: URL: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/Consortium/HP2020Framework.pdf.

- 32.World Health Assembly. Health-for-all policy for the twenty-first century. Fifty-first World Health Assembly, agenda item 19: resolution WHA51.7 May 16, 1998. [cited 2013 Aug 8]. Available from: URL: http://www.nszm.cz/cb21/archiv/material/worldhealthdeclaration.pdf.

- 33.Dunne FP. New York: R.H. Russell; 1902. Observations by Mr. Dooley. [Google Scholar]