Abstract

Objective

Multiple interventions have been shown to reduce the risk of HIV acquisition, including preexposure prophylaxis with antiretroviral medications, but high costs require targeting interventions to people at the highest risk. We identified the risk of HIV following a syphilis diagnosis for men in Florida.

Methods

We analyzed surveillance records of 13- to 59-year-old men in Florida who were reported as having syphilis from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2009. We excluded men who had HIV infection reported before their syphilis diagnosis (and within 60 days after), then searched the database to see if the remaining men were reported as having HIV infection by December 31, 2011.

Results

Of the 9,512 men with syphilis we followed, 1,323 were subsequently diagnosed as having HIV infection 60–3,753 days after their syphilis diagnosis. The risk of a subsequent diagnosis of HIV infection was 3.6% in the first year after syphilis was diagnosed and reached 17.5% 10 years after a syphilis diagnosis. The risk of HIV was higher for non-Hispanic white men (3.4% per year) than for non-Hispanic black men (1.8% per year). The likelihood of developing HIV was slightly lower for men diagnosed with syphilis in 2000 and 2001 compared with subsequent years. Of men diagnosed with syphilis in 2003, 21.5% were reported as having a new HIV diagnosis by December 31, 2011.

Conclusion

Men who acquire syphilis are at very high risk of HIV infection.

Antiretroviral medications have reduced acquired immunodeficiency syndrome mortality in the United States from 50,260 adults in 1995 to 17,770 adults in 2009.1,2 However, the risk of acquiring human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection remains high, particularly for men who have sex with men (MSM). An estimated 30,000 MSM have acquired HIV in each of the past several years.3,4 The White House's National HIV/AIDS Strategy states that to reduce HIV incidence, we must (1) intensify HIV prevention efforts in communities where HIV is most heavily concentrated and (2) expand targeted efforts to prevent HIV infection using a combination of effective, evidence-based approaches.5 By estimating the percentage of men in the population who are MSM, researchers have estimated the HIV incidence for all MSM as 0.66% per year in Florida (in 2006)6 and 0.67% per year in 37 states (in 2008).7 This risk might be reduced by a variety of interventions, including antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which reduced the incidence of HIV by 44% among MSM in a blinded randomized controlled trial.8 If PrEP could be widely implemented with high-use effectiveness, it could have an impact on HIV incidence; however, the high cost of PrEP will require targeting MSM at highest risk.9 Some groups of high-risk MSM have been identified. For example, MSM recruited into HIV vaccine efficacy studies have had incidence rates as high as 2.7% per year.10

People diagnosed with other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) have long been known to be at increased risk for having HIV coinfection.11 Among 212 men with early syphilis in Los Angeles, California, in 2002–2004, 35% had HIV coinfection, and HIV incidence was estimated to be 17% in the preceding year.12 Among 363 MSM with early syphilis in Atlanta, Georgia; San Francisco, California; or Los Angeles in 2004–2005, 47% had HIV coinfection, and 10 of these coinfections were recently diagnosed, suggesting an incidence of 12%.13 However, preventing infection requires identifying high-risk people before they acquire HIV. A recent study in San Francisco's City Clinic retrospectively followed MSM for two years after they were diagnosed with rectal gonorrhea or chlamydia and found that 27 acquired HIV, for an incidence of 2.3% per year.14

In Florida, all syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia infections are reportable to the state health department, and the reports are maintained in a common database. This database is routinely cross-matched with the HIV surveillance database to determine if any of the people with other STIs have been reported as having HIV. Gender of sex partners is not available for all reported cases of STI, but since the early 2000s, syphilis cases have been increasingly concentrated among MSM.15 We used this database to study all men in Florida who were reported as having early syphilis and to determine their risk of subsequent diagnosis and report of HIV infection.

METHODS

We analyzed all records of 13- to 59-year-old men in Florida reported as having syphilis from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2009. Syphilis diagnoses were included if they were classified as primary, secondary, early latent, or late latent if the individual had nontreponemal antibody detectable at dilutions ≥1:32, which suggests recent infection. We took the first episode of syphilis, excluded men with known HIV infection at the time of their first diagnosis (or within 60 days of their first diagnosis), then searched the database to see if the remaining men had been newly reported as having HIV infection at least 60 days following their syphilis diagnosis. Follow-up for HIV included all diagnoses before December 31, 2011, that were reported by March 19, 2012. We compared estimates of risk for a new diagnosis of HIV for various subgroups by race/ethnicity, age group, location, and year of syphilis diagnosis. Age was recorded as the age at the time of syphilis diagnosis, and location was classified as the residence at the time of the syphilis diagnosis, even if the HIV infection was reported from another location in Florida. High-risk areas were defined (using all reported HIV infections) as ZIP Codes where at least 200 men aged 13–59 years were reported with newly diagnosed HIV infection from 2000 to 2011, and where the average annual rate of HIV diagnoses per 100,000 men was at least 200. Survival analyses were performed using the LIFETEST procedure in SAS® version 9.316 to calculate the time between syphilis and HIV diagnoses, with censoring at the end of 2011. We assessed changes in HIV risk over time by plotting cumulative percentages with newly reported HIV following the diagnosis of syphilis for cohorts of men based on the year of their syphilis diagnosis (2000–2009).

Trends in syphilis rates among MSM in Florida were estimated using primary, secondary, and early latent cases reported for men and women of all ages and population estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau. We estimated the number of men with syphilis who were MSM using the assumption that the male-to-female rate ratio of primary and secondary syphilis would be 1.26 if there were no MSM.17 For each year, we calculated the proportion of men with primary and secondary syphilis who were MSM—([male rate/female rate]−1.26)/(male rate/female rate)—and multiplied that proportion by the number of early syphilis cases for all males.

RESULTS

From January 2000 to December 2009, a first episode of early or high-titer syphilis was reported for 13,580 men aged 13–59 years. Of those men, 4,068 (30.0%) were already known to be infected with HIV or were reported as having HIV within 60 days of their syphilis diagnosis. After omitting these men, 9,512 men were left who could be followed for a new diagnosis of HIV infection. Their median age was 35 years (mean: 35.1 years) (data not shown) with a broad age distribution (Table). Most of the men were non-Hispanic black (39.2%), followed by non-Hispanic white (29.7%), Hispanic (20.4%), and unknown/other (10.7%).

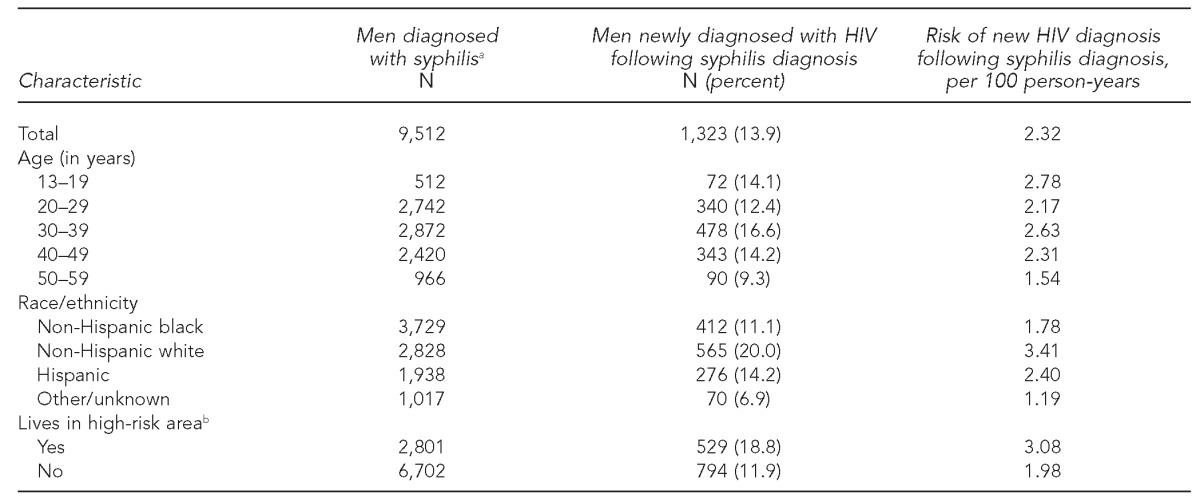

Table.

Risk of new HIV diagnosis following a syphilis diagnosis among men aged 13–59 years: Florida, 2000–2011

aIncludes men diagnosed with syphilis from 2000 to 2009 who did not have a prior HIV diagnosis

bHigh-risk areas were defined (using all reported HIV infections) as ZIP Codes where ≥200 men aged 13–59 years were reported with newly diagnosed HIV infection from 2000 to 2011, and where the average annual rate of HIV diagnoses per 100,000 men was ≥200.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

During 57,142 person-years of follow-up, we identified 1,323 men diagnosed with HIV 60–3,753 days after syphilis was diagnosed (mean follow-up was 6.0 years and mean time to HIV diagnosis was 2.7 years). The risk of a subsequent diagnosis of HIV infection was 2.3% per year for all men who were diagnosed with syphilis. The risk of developing HIV after syphilis did not change appreciably with age at the time of syphilis diagnosis, although it was slightly lower for men who were aged 50–59 years at the time of diagnosis (1.5% per year). The risk of HIV was higher for non-Hispanic white men (3.4% per year) than for non-Hispanic black men (1.8% per year). Men who lived in high-risk ZIP Codes were 1.6 times as likely as men from low-risk ZIP Codes to be reported as having HIV after a diagnosis of syphilis (Table).

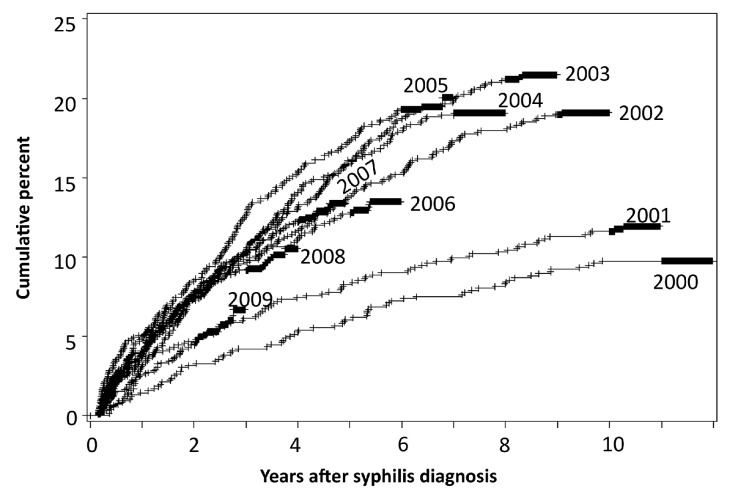

The likelihood of being diagnosed with HIV was highest in the years immediately following the diagnosis of syphilis, reaching 3.6% per year. However, the risk continued to accumulate for many years, reaching 21.5% after 8.3 years for men diagnosed with syphilis in 2003 (Figure). For all years combined, the life table risk was 17.5% after 10 years. The likelihood of being reported with HIV was slightly lower for men diagnosed with syphilis in 2000 and 2001, and perhaps 2009, but was otherwise similarly high for all diagnosis-year cohorts. When curves were plotted for HIV diagnosis among non-Hispanic white men only, they were generally the same shape, but reached as high as 26.0% eight years after syphilis diagnosis for men diagnosed with syphilis in 2002 or 2003 (data not shown).

Figure.

Cumulative percent of men aged 13–59 years with newly reported HIV infection following syphilis diagnosis,a by year of syphilis diagnosis: Florida, 2000–2011

aSyphilis diagnosed from 2000 to 2009

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

The number of men reported with primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis (i.e., early syphilis) in Florida increased from 843 in 2000 to 2,109 in 2011, while the male-to-female rate ratio for primary and secondary syphilis increased from 1.60 to 8.71, with the greatest increases occurring from 2000 to 2003. For the syphilis cohort years included in our study (2000–2009), we estimate that 73.0% of the men were MSM. The estimated number of MSM reported with early syphilis increased tenfold, from 179 in 2000 to 1,804 in 2011.

DISCUSSION

The link between syphilis and HIV infection is multidimensional and evolving. Early studies established that syphilitic ulcers could facilitate HIV transmission or acquisition, but later studies found little population-level impact of treating syphilis as an HIV prevention intervention.11 We studied syphilis as a marker for people who are at high risk for acquiring HIV after the syphilis has been treated. In the year after syphilis was diagnosed, we found an extremely high risk of a new HIV diagnosis (3.6%), and that risk continued to accumulate, reaching 21.5% after 8.3 years for men who had syphilis diagnosed in 2003. Even this risk likely underestimates the risk for MSM with syphilis because about 27% of the men we studied were heterosexual. There is no evidence that this risk is declining.

MSM with syphilis could be targeted for HIV prevention efforts. Counseling may be particularly effective if the acquisition of syphilis helps them recognize their risk for HIV. Many risk-reduction strategies have been shown to be effective,18 and counseling can help men choose which strategy is right for them. Using condoms consistently and correctly, testing partners and treating those who are HIV-infected, and taking antiretrovirals for PrEP might reduce risk if adhered to regularly and without too much compensatory behavior change that increases risk.

At the population level, the syphilis and HIV epidemics among MSM are increasingly intertwined, and both have persistently high incidence rates. The number of MSM reported with syphilis in Florida in 2011 was 10 times the number from 2000. Many of the men who acquired syphilis were already HIV-coinfected. Among men and women with early syphilis in Florida, HIV coinfection at the time of syphilis diagnosis increased from 6.7% in 2000 to 18.0% in 2005 to 42.3% in 2010.19 Our study found that men with syphilis who were not known to be HIV-infected were very likely to have HIV infection reported in subsequent years. High risks for syphilis and HIV among MSM have been documented elsewhere. From 2005 to 2008, estimated HIV diagnosis rates more than doubled (reaching 8.9% per year) and primary and secondary syphilis rates increased sixfold (reaching 2.9% per year) among 18- to 29-year-old MSM in New York City.20 These population-level trends suggest a need for public health action that addresses socioeconomic factors and helps change the context for MSM so that individuals' default decisions are healthy.21

LIMITATIONS

This study was subject to several limitations. We did not have information on gender of sex partners for many of the men. We did not actively follow men after testing them to be sure they were HIV uninfected. We measured the risk of being reported as having HIV in Florida, not true HIV incidence. This time to diagnosis and reporting is longer than the time to infection. Our estimates would overestimate HIV incidence if HIV-infected men were not tested for HIV at the time of their syphilis diagnosis and infections discovered later were considered to have occurred after the syphilis diagnosis. Although we cannot be sure that the men who were diagnosed with HIV after syphilis actually acquired HIV after syphilis, the sustained high risk for several years suggests that the men were at sustained high risk for acquiring HIV. Our estimates would underestimate incidence risk if men later acquired HIV but were not detected by our database because they were not tested or because they moved away from Florida and HIV infection was diagnosed elsewhere. Finally, men who were diagnosed with syphilis while living outside of Florida would not be considered syphilis-associated if they were later reported to have HIV in Florida.

CONCLUSION

Men in Florida who were diagnosed with syphilis were very likely to be diagnosed with HIV in the ensuing years. Targeting the individual men who get syphilis and offering interventions such as intensive counseling and PrEP would likely reduce their risk and improve their health. However, of the 3,102 MSM diagnosed with HIV in Florida in 2010,2 only 154 (5.0%) had syphilis diagnosed in Florida from 2000 to 2009, so the benefits to the individuals with syphilis are unlikely to translate into a major reduction in HIV incidence at the population level. The increasing rates of syphilis, which can be cured with one dose of medication, suggest we will have trouble controlling HIV, which requires daily medication for life. However, syphilis rates have decreased among heterosexuals in the U.S., and HIV incidence has decreased in some countries.22 Developing effective interventions for men at highest risk may help with the development of interventions for the rest of the population.

Footnotes

This study was conducted by employees of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Florida Department of Health (FDH) as part of their normal duties, without additional funding. CDC staff did not have access to personal identifiers. Secondary analyses of routinely collected surveillance data without personal identifiers do not involve human subjects; therefore, they are not subject to review by the CDC Institutional Review Board.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of CDC or FDH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. No. 2. Vol. 12. Atlanta: CDC; 2000. U.S. HIV and AIDS cases reported through December 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention Atlas. [cited 2012 Dec 14]. Available from: URL: http://gis.cdc.gov/GRASP/NCHHSTPAtlas/main.html.

- 3.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, Prejean J, An Q, Lee LM, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:520–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, Ziebell R, Green T, Walker F, et al. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White House (US) Washington: White House Office of National AIDS Policy; 2010. National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lieb S, White S, Grigg BL, Thompson DR, Liberti TM, Fallon SJ. Estimated HIV incidence, prevalence, and mortality rates among racial/ethnic populations of men who have sex with men, Florida. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54:398–405. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181d0c165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Purcell DW, Johnson CH, Lansky A, Prejean J, Stein R, Denning P, et al. Estimating the population size of men who have sex with men in the United States to obtain HIV and syphilis rates. Open AIDS J. 2012;6:98–107. doi: 10.2174/1874613601206010098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2587–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juusola JL, Brandeau ML, Owens DK, Bendavid E. The cost-effectiveness of preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in the United States in men who have sex with men. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:541–50. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-8-201204170-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ackers ML, Greenberg AE, Lin CY, Bartholow BN, Goodman AH, Longhi M, et al. High and persistent HIV seroincidence in men who have sex with men across 47 U.S. cities. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayes R, Watson-Jones D, Celum C, van de Wijgert J, Wasserheit J. Treatment of sexually transmitted infections for HIV prevention: end of the road or new beginning? AIDS. 2010;24(Suppl 4):S15–26. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000390704.35642.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor MM, Hawkins K, Gonzalez A, Buchacz K, Aynalem G, Smith LV, et al. Use of the serologic testing algorithm for recent HIV seroconversion (STARHS) to identify recently acquired HIV infections in men with early syphilis in Los Angeles County. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38:505–8. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000157390.55503.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buchacz K, Klausner JD, Kerndt PR, Shouse RL, Onorato I, McElroy PD, et al. HIV incidence among men diagnosed with early syphilis in Atlanta, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, 2004 to 2005. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:234–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernstein KT, Marcus JL, Nieri G, Philip SS, Klausner JD. Rectal gonorrhea and chlamydia reinfection is associated with increased risk of HIV seroconversion. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:537–43. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c3ef29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Atlanta: CDC; 2012. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.SAS Institute, Inc. SAS®: Version 9.3 for Windows. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heffelfinger JD, Swint EB, Berman SM, Weinstock HS. Trends in primary and secondary syphilis among men who have sex with men in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1076–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.070417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curran K, Baeten JM, Coates TJ, Kurth A, Mugo NR, Celum C. HIV-1 prevention for HIV-1 serodiscordant couples. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2012;9:160–70. doi: 10.1007/s11904-012-0114-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Florida Department of Health. STD trends and statistics. [cited 2012 Nov 30]. Available from: URL: http://www.doh.state.fl.us/disease_ctrl/std/trends/florida.html.

- 20.Pathela P, Braunstein SL, Schillinger JA, Shepard C, Sweeney M, Blank S. Men who have sex with men have a 140-fold higher risk for newly diagnosed HIV and syphilis compared with heterosexual men in New York City. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58:408–16. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318230e1ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:590–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoneburner RL, Low-Beer D. Population-level HIV declines and behavioral risk avoidance in Uganda. Science. 2004;304:714–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1093166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]