Abstract

There are few validated acculturation measures for Asian Indians in the U.S. We used the 2004 California Asian Indian Tobacco Survey to examine the relationship between temporal measures and eleven self-reported measures of acculturation. These items were combined to form an acculturation scale. We performed psychometric analysis of scale properties. Greater duration of residence in the U.S., greater percentage of lifetime in the U.S., and younger age at immigration were associated with more acculturated responses to the items for Asian Indians. Item-scale correlations for the 11-item acculturation scale ranged from 0.28–0.55 and internal consistency reliability was 0.73. Some support was found for a two-factor solution; one factor corresponding to cultural activities (α = 0.70) and the other to social behaviors (α = 0.59). Temporal measures only partially capture the full dimensions of acculturation. Our scale captured several domains and possibly two dimensions of acculturation.

Keywords: Asian Indian, Duration of residence, Acculturation

Introduction

Foreign-born residents, or immigrants, comprise an increasingly significant proportion of the United States (U.S.) population, but have been underserved in public health promotion [1]. Acculturation to U.S. cultural practices by immigrants is associated with greater likelihood of having chronic health conditions [2]. However, the estimated health impact of acculturation depends on how acculturation is measured [3, 4].

Acculturation was initially conceptualized as a unidirectional process where immigrants acquired the values, practices, and beliefs of their new homeland while simultaneously discarding those from their cultural heritage [5]. More recent views of acculturation acknowledge that immigrants frequently maintain features of their original culture in their personal lives and adapt to their host culture in their public lives [6–8]. Nonetheless, unidirectional measures of acculturation are still widely used [3, 4, 9].

Language preference, country of nativity, and duration of residence in the U.S. are used as proxy measures of acculturation in Latino and Asian immigrant health studies [3, 4]. However, language use may not be an adequate proxy for Asian Indians because many were exposed to English language from an early age in elementary school classes taught in India [10]. Duration of residence in the host country has also been criticized as a proxy measure because the Indian diaspora led to many Asian Indians living in other developed countries where they were exposed to Western cultural values prior to immigrating to the U.S. [11].

Measures that assess several domains of acculturation, such as social relationships, cultural activities, and linguistic preference, are thought to be more valid than proxy measures [12, 13]. However, many scales lack a conceptual framework of acculturation and are rarely used in studies evaluating health behaviors or outcomes because of respondent burden and costs [3]. Given that proxy measures are often the only available indicators of acculturation in many of the data sets routinely used to study the health of Asian Americans, it is important to know how valid they are as measures of acculturation.

The California Asian Indian Tobacco Survey (CAITS) provides an opportunity to evaluate temporal measures of acculturation, such as duration of residence in the U.S. CAITS was a multilingual, population-based assessment of Asian Indians that contains several measures of acculturation. Our objective was to examine the association of temporal measures with self-reported measures of acculturation among Asian Indians, one of the fastest growing ethnic groups in the U.S. [14]. In addition, given that no commonly accepted acculturation scale exists for Asian Indians, we created an acculturation scale using existing survey items and report the properties of the scale.

Methods

Data Source

CAITS was a 27-min multilingual (English, Gujarati, Hindi, or Punjabi) telephone tobacco use and health survey administered to 3,228 adults of Asian Indian background and resident in California in 2004 [15]. Surnames for CAITS were compiled from names from Social Security [16] and through the Vital Statistic Office for the California Department of Health Services from 1998–2002. Using a stratified random sample, CAITS had a household response rate of 67% and randomly selected interviewee response rate of 81% [15]. We received IRB exemption from the University of California, Los Angeles for these analyses (IRB#12-000582).

Measures

Three temporal measures of acculturation were examined as dependent variables: duration of residence in the U.S., percentage of lifetime in the U.S., and age at immigration. Duration of residence in years was calculated by subtracting the survey year from the year the respondent entered the U.S. Percentage of lifetime was calculated from duration of residence in the U.S. divided by respondent’s current age, and age at immigration was calculated from year entered the U.S. minus the respondent’s birth year. These measures were only answered by foreign-born respondents (90% of the sample).

Acculturation measures were 11 questions that represented six aspects of acculturation: language use, media behavior, social customs, social contacts, cultural identity, and generational status. These items have been included in existing scales of acculturation [9, 12, 13]. Table 1 provides a description of the core items and possible responses. “Language of the interview” was dichotomized into English or Asian Indian language. “How open would you be to your son marrying outside of cultural group” and “How open would you be to your daughter marrying outside of cultural group?” correlated at r = 0.95. To deal with local dependency, we generated a new variable “How open would you be to your child marrying outside of cultural group” using the average of the two responses. Of note, respondents were not given a definition or characteristics of a cultural group prior to their response. “Nativity” (born in a developed versus non-developed country) and “Generational status” correlated at r = 0.75 and responses from both questions were averaged together as a single item.

Table 1.

Acculturation Scale core items, lower-level domains, and responses

| Items | Responses |

|---|---|

| Language use | |

| 1. English as primary language | 1 = No |

| 2 = Yes | |

| 2. How often native language spoken at home? | 1 = Very often |

| 2 = Somewhat often | |

| 3 = Neither often nor rarely | |

| 4 = Somewhat rarely | |

| 5 = Very rarely | |

| 3. Language of interview | 1 = Hindi, Punjabi, Gujarati |

| 2 = English | |

| Media behavior | |

| 4. How often do you read Indian newspapers, magazines, books? | 1 = Very often |

| 2 = Somewhat often | |

| 3 = Neither often nor rarely | |

| 4 = Somewhat rarely | |

| 5 = Very rarely | |

| Social customs | |

| 5. How often do you eat Indian food? | 1 = Very often |

| 2 = Somewhat often | |

| 3 = Neither often nor rarely | |

| 4 = Somewhat rarely | |

| 5 = Very rarely | |

| 6. How open are you to your child marrying outside of cultural group? | 1 = Strongly against |

| 2 = Moderately against | |

| 3 = Neither open or against | |

| 4 = Moderately open | |

| 5 = Very open | |

| 7. Do you observe the traditional holidays in your culture/religion? | 1 = Yes, almost always |

| 2 = Yes, much of the time | |

| 3 = Yes, some of the time | |

| 4 = No, rarely or never | |

| Social contacts | |

| 8. How often do you keep in contact with family/friends in India? | 1 = Very often |

| 2 = Somewhat often | |

| 3 = Neither often nor rarely | |

| 4 = Somewhat rarely | |

| 5 = Very rarely | |

| Ethnic identity | |

| 9. What is your cultural identity? | 1 = Full-Indian |

| 2 = Indian first-American second | |

| 3 = Equal blend of Indian-American | |

| 4 = American first-Indian second | |

| 5 = Full American | |

| Generational status | |

| 10. What is your generational status? | 1 = 1st generation |

| 2 = 2nd+generation | |

| 11. Were you born in a developed country? | 1 = No |

| 2 = Yes |

Analysis Plan

First, we examined the mean number of years lived in the U.S., mean percentage of lifetime in the U.S., and mean age at immigration by responses to the acculturation items. Responses to the acculturation items were analyzed both in their original categories and after dichotomization, but we only report the former because the results were similar. We also conducted standard contingency table analysis to identify meaningful temporal measure cut-off points that differed between more American acculturated responses and less acculturated responses [17]. The reference category was a dichotomized acculturation item and the classification category was the temporal measure [17]. Acculturation items were dichotomized as 0 for less acculturated or 1 for more acculturated to American culture. For example, responses for “how often do you keep in contact with family and friends in India?” were dichotomized into those who responded “very often,” “somewhat often,” or “neither often or rarely” versus those who responded “somewhat rarely” or “very rarely”. We used a specificity cut point ≥0.70.

Second, we conducted exploratory factor analyses to evaluate the dimensionality of the items in the overall acculturation scale [18]. Several factor criteria (Guttman’s weakest lower bound, scree plot, eigenvalue >1, and parallel analysis) were examined to help determine the number of factors. Oblique factor rotations were then run for the plausible number of underlying factors. Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to evaluate the fit of alternative models for the data. The goodness-of-fit of the confirmatory factor analysis models was evaluated using the Chi square statistic, the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA). Models with a CFI of 0.90 and RMSEA ≤0.06 may be considered acceptable [18, 19].

Third, we transformed linearly the recoded 11 acculturation scale items to a 0–100 possible range. For example, the item “how often do you speak your native language at home?” had five response categories labeled 1 through 5 that were recoded to 0, 25, 50, 75, 100 (Table 1). The 11 items were then averaged together to produce the scale score. Item descriptives, item-scale correlations, internal consistency reliability (coefficient alpha), and Pearson product-moment correlations of the scale with the temporal measures were estimated.

Post-stratification weights were used in the analyses to correct for non-coverage (surname omitted from sampling frame) and differential non-response. The post-stratification adjustments were stratified by gender and age grouping, and counties were grouped by 12 California regions used in previous tobacco control research [15]. The analyses were conducted using STATA 11.2.

Results

Sample Demographics

The average age of the sample was 37 years (Table 2). Most respondents were male and well-educated. Foreign-born respondents had a mean duration of residence in the U.S. of 13 years, or one-third of their lifetime spent in the U.S. The median age at immigration to the U.S. was 25 years old.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Asian Indian adults in the CAITS dataset, n = 3,228

| n | % or median, mean |

Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median, mean +/− SD (range) | 3,199 | 35 years, 37 years +/− 13 | (18–88) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1,782 | 52% | |

| Female | 1,446 | 48% | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 2,502 | 73% | |

| Not married | 711 | 27% | |

| Education level | |||

| ≤ High school graduate | 350 | 12% | |

| > High school graduate | 2,872 | 88% | |

| Temporal measuresa | |||

| Duration of residence in U.S., median, mean +/− SD (range) | 2,951 | 9 years, 13 years +/− 10 | (0–56) |

| Proportion of lifetime in U.S., median, mean +/− SD (range) | 2,951 | 26%, 32% +/− 22 | (0–100) |

| Age at immigration, median, mean +/− SD (range) | 2,951 | 25 years old, 26 years old +/− 11 | (0–75) |

Categories may not sum to total N or 100% due to missing observations or rounding

Survey sampling weights applied to percentage of sample

Temporal measures answered only by foreign-born respondents or 90% of parent sample

Construct Validity of Temporal Measures

In general, greater duration of residence in the U.S., greater percentage of lifetime in the U.S., and younger age at immigration were associated with endorsing items indicative of increased acculturation (Table 3). Specifically, with increasing duration of residence in the U.S., Asian Indian immigrants were more likely to prefer English as their primary language (mean duration 10.7 years for non-English as primary language versus mean duration 14.4 years for English as primary language, p < 0.001) and as their preferred language used in the interview (9.9 years for non-English interview vs. 12.8 years for English interview, p < 0.001). Asian Indian immigrants who had lived for a greater duration in the U.S. were less likely to speak their native language at home (very often for 11 years vs. very rarely for 18 years, p < 0.001), read Indian media (very often for 10 years vs. very rarely for 15 years, p < 0.001), observe traditional cultural or religious holidays (almost always for 12 years vs. rarely or never for 14 years, p < 0.001), and stay in contact with family and friends in India (very often for 10 years vs. very rarely for 18 years, p < 0.001). Living more years in the U.S. was significantly associated with second or greater generational status and with respondent birth in a developed country.

Table 3.

Relationship of temporal measures with acculturation domains for Asian Indians (95 % CI)

| % sample |

Mean duration in U.S. (years) |

Correlation with duration |

Mean % lifetime in U.S. |

Correlation with % lifetime |

Mean age at immigration (years) |

Correlation with age at immigration |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language use | |||||||

| English as primary language | |||||||

| Yes | 48 | 14.4 (13.8,15.0) | 0.21 | 37.8 (36.3, 39.4) | 0.26 | 22.6 (22.0, 23.2) | −0.23 |

| No | 52 | 10.7 (10.2,11.2) | 26.9 (25.8, 28.0) | 27.8 (27.2, 28.5) | |||

| How often native language spoken at home? | |||||||

| Very often | 66 | 10.7 (10.2, 11.1) | 0.28 | 27.7 (26.7, 28.7) | 0.27 | 26.9 (26.3, 27.4) | −0.17 |

| Somewhat often | 18 | 14.4 (13.3, 15.4) | 37.4 (34.7, 40.0) | 23.4 (22.3, 24.5) | |||

| Neither often nor rarely | 3 | 14.7 (12.6, 16.8) | 39.9 (34.4, 45.5) | 21.9 (19.4, 24.4) | |||

| Somewhat rarely | 6 | 18.8 (16.6, 20.9) | 47.2 (42.0, 52.4) | 20.3 (18.3, 22.2) | |||

| Very rarely | 6 | 18.3 (16.2, 20.5) | 41.7 (37.6, 45.8) | 22.7 (21.1, 24.2) | |||

| Language of interview | |||||||

| English | 89 | 12.8 (12.4,13.3) | 0.11 | 33.7 (32.6, 34.7) | 0.18 | 23.7 (23.3, 24.1) | −0.36 |

| Hindi, Punjabi, Gujarati | 11 | 9.9 (9.0, 10.7) | 22.0 (20.2, 23.7) | 36.5 (34.8, 38.2) | |||

| Media behavior | |||||||

| How often do you read Indian media? | |||||||

| Very often | 28 | 10.1 (9.5, 10.8) | 0.21 | 25.7 (24.5, 27.0) | 0.24 | 27.2 (26.4, 28.0) | −0.13 |

| Somewhat often | 25 | 11.5 (10.7, 12.2) | 29.6 (27.8, 31.4) | 25.9 (25.1, 26.8) | |||

| Neither often nor rarely | 6 | 13.3 (11.8, 14.9) | 35.0 (31.1, 39.0) | 25.1 (22.8, 27.3) | |||

| Somewhat rarely | 15 | 13.9 (12.8, 15.0) | 36.6 (33.9, 39.4) | 23.7 (22.4, 25.0) | |||

| Very rarely | 26 | 15.4 (14.5, 16.3) | 39.9 (37.8, 42.1) | 23.0 (21.9, 24.0) | |||

| Social customs | |||||||

| How often do you eat Indian food? | |||||||

| Very often | 81 | 11.8 (11.4, 12.2) | 0.15 | 30.4 (29.4, 31.3) | 0.17 | 26.1 (25.6, 26.6) | −0.14 |

| Somewhat often | 14 | 16.0 (14.6, 17.3) | 41.4 (38.1, 44.7) | 21.2 (19.9, 22.5) | |||

| Neither often nor rarely | 2 | 16.4 (13.4, 19.5) | 44.4 (36.8, 52.0) | 20.2 (17.1, 23.3) | |||

| Somewhat rarely | 2 | 16.2 (12.4, 19.9) | 46.5 (35.3, 57.6) | 18.0 (14.5, 21.4) | |||

| Very rarely | 1 | 13.8 (9.2, 18.5) | 35.2 (26.7, 43.8) | 22.8 (18.5, 27.1) | |||

| Openness to child marrying outside group? | |||||||

| Very open | 36 | 14.3 (13.6, 15.1) | 0.10 | 36.7 (34.9, 38.6) | 0.10 | 23.5 (22.7, 24.3) | −0.14 |

| Moderately open | 28 | 11.4 (10.7, 12.2) | 29.3 (27.7, 31.0) | 25.1 (24.5, 25.8) | |||

| Neither open or against | 17 | 11.9 (11.0, 12.8) | 31.5 (29.2, 33.8) | 25.9 (24.7, 27.2) | |||

| Moderately against | 9 | 12.0 (10.7, 13.3) | 30.9 (27.8, 34.1) | 27.2 (25.4, 29.1) | |||

| Strongly against | 9 | 11.6 (10.5, 12.8) | 30.4 (27.4, 33.5) | 27.9 (26.0, 29.8) | |||

| Observance of traditional holidays? | |||||||

| Yes, almost always | 33 | 11.9 (11.2, 12.6) | 0.10 | 30.8 (29.1, 32.5) | 0.11 | 26.7 (25.8, 27.6) | −0.12 |

| Yes, much of the time | 23 | 12.0 (11.2, 12.8) | 31.3 (29.4, 33.2) | 25.5 (24.5, 26.5) | |||

| Yes, some of the time | 32 | 12.8 (11.2, 12.8) | 32.9 (31.2, 34.6) | 24.4 (23.7, 25.1) | |||

| No, rarely or never | 12 | 14.4 (13.1, 15,7) | 36.8 (33.9, 40.0) | 22.9 (21.7, 24.2) | |||

| Social contacts | |||||||

| How often in contact with family/friends in India? | |||||||

| Very often | 57 | 10.2 (9.7, 10.6) | 0.26 | 26.7 (25.8, 27.7) | 0.28 | 25.9 (25.4, 26.4) | −0.04 |

| Somewhat often | 23 | 14.9 (14.0, 15.8) | 37.0 (34.9, 39.1) | 25.1 (24.1, 26.1) | |||

| Neither often nor rarely | 4 | 15.7 (13.5, 18.0) | 43.2 (36.6, 49.7) | 22.8 (19.3, 26.3) | |||

| Somewhat rarely | 7 | 17.2 (15.4, 19.0) | 43.5 (39.0, 48.0) | 24.9 (22.2, 27.7) | |||

| Very rarely | 9 | 17.5 (15.9, 19.0) | 46.2 (42.1, 50.3) | 22.5 (20.4, 24.7) | |||

| Ethnic identity | |||||||

| Self-assessed cultural identity | |||||||

| Full Indian | 24 | 7.6 (7.1, 8.1) | 0.32 | 21.5 (20.2, 22.8) | 0.30 | 26.6 (25.8, 27.4) | −0.05 |

| Indian first-American second | 16 | 12.3 (11.3, 13.2) | 32.7 (30.3, 35.2) | 24.9 (23.8, 26.1) | |||

| Equal blend Indian-American | 50 | 14.4 (13.8, 15.0) | 36.4 (35.0, 37.8) | 24.9 (24.1, 25.6) | |||

| American first-Indian second | 6 | 17.1 (15.0, 19.2) | 42.2 (37.1, 47.3) | 23.9 (21.4, 26.5) | |||

| Full American | 4 | 18.7 (16.3, 21.2) | 44.1 (38.2, 50.1) | 23.7 (20.8, 26.6) | |||

| Generational status | |||||||

| Nativity | |||||||

| Born in developed country | 10 | 15.6 (13.3, 18.0) | 0.05 | 51.1 (43.5, 58.6) | 0.14 | 15.0 (12.5, 17.5) | −0.16 |

| Not born in a developed country | 90 | 12.3 (11.9, 12.7) | 31.4 (30.4, 32.3) | 25.7 (25.2, 26.2) | |||

| Generational Status | |||||||

| 1st generation | 88 | 11.8 (11.5, 12.2) | 0.26 | 29.2 (28.4, 29.9) | 0.54 | 26.5 (26.0, 26.9) | −0.42 |

| 2+ generationa | 12 | 24.6 (23.2, 26.0) | 91.1 (89.6, 92.7) | 2.3 (1.9, 2.6) | |||

F test p value <0.0001 for all items except: Duration of residence in U.S.—country of birth with F(1, 2876) = 8.59, p value = 0.0034; Age at immigration—contact with family/friends with F(4, 2917) = 1.84, p value = 0.12 and ethnic identity with F(4, 2847) = 2.12, p = 0.08

Respondents who were born abroad but immigrated to the U.S. before age 6 were categorized as 2nd generation, culturally

There was a non-linear relationship between frequency of Indian food consumption or openness to respondent’s child marrying outside the cultural group and duration of residence in the U.S. Small sample sizes in some response categories may explain the lack of a linear relationship; inappropriate measures of acculturation for Asian Indians may be another explanation. For example, marriage outside of a cultural group may have been interpreted as marriage to someone of Indian descent but of a different Indian language/culture/religion, as opposed to marriage to someone of a different race/ethnicity.

Contingency table analysis suggested a meaningful cutoff at 12–16 years duration of residence in the U.S. and 34–40% for percentage of lifetime in the U.S. between respondents who were more versus less acculturated to American culture. Product-moment correlations between self-reported acculturation items and duration of residence in the U.S. ranged from r = 0.05 for generational status to r = 0.32 for ethnic identity. Correlations of percentage of lifetime in the U.S. with acculturation items ranged from r = 0.10 for marriage of child outside cultural group to r = 0.54 for generational status. Age at immigration had a negative linear relationship with most acculturation items except native language spoken at home, frequency of Indian food consumption, and contacts with family and friends in India. Correlations between acculturation items and age at immigration ranged from r = −0.04 for contact with family and friends in India to r = −0.42 for generational status. Age at immigration had a meaningful cut-off at 29–31 years of age between the more versus less acculturated respondents. We would expect measures that assess acculturation domains to be negatively correlated with age at immigration because acculturation varies depending on whether the immigrant arrived as an adult or as a child, with the latter group more closely resembling the native-born population reportedly due to less exposure and ties to their country of origin [20].

Acculturation Scale

Various factor criteria suggested that between 2 and 4 factors were sufficient to explain most of the shared variance. Simple structure was optimized for the two-factor Promax obliquely rotated solution (Table 4). The estimated correlation between the two factors was 0.23: Factor 1 appears to represent frequency of engaging in Indian cultural behaviors (home language preference, preference for Indian media, preference for Indian food, Indian social contacts, ethnic identity, and generational status) and Factor 2 corresponds to the influence of Indian culture on social behaviors in the U.S. (English preference and use in interview, and two social customs of observance of traditional holidays and openness to child marrying outside of cultural group). To improve model fit, we estimated five correlated errors suggested by Lagrange multiple indices. Factor loadings were statistically significant and moderate to large in size (Table 5). The CFI for the two-factor model was 0.89 and the RMSEA was 0.07, suggestive of an acceptable fit [16, 17].

Table 4.

Promax obliquely rotated two-factor solution (standardized regression coefficients)

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Social contacts | ||

| 8. How often keep in contact with family and friends in India | 0.7880 | −0.2501 |

| Media Behavior | ||

| 4. How often read Indian newspapers, magazines, books | 0.6329 | −0.0152 |

| Generational status | ||

| 10. Generational status/Born in developed country | 0.5939 | −0.0114 |

| Language use | ||

| 2. How often native language spoken at home | 0.5278 | 0.3916 |

| Social customs | ||

| 5. How often eat Indian food | 0.5016 | 0.2014 |

| Ethnic identity | ||

| 9. Self-assessed cultural identity | 0.4821 | 0.0725 |

| Language use | ||

| 3. Language of interview | −0.1503 | 0.7570 |

| Social customs | ||

| 6. How open to child marrying outside cultural group | −0.0703 | 0.7177 |

| Language use | ||

| 1. English as primary language | 0.2464 | 0.5688 |

| Social customs | ||

| 7. Do you observe the traditional holidays important in your culture | 0.0958 | 0.5216 |

Bold values represents substantial factor loading, or loading higher than 0.40

Factor 1: Items 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 10; Factor 2: Items 1, 3, 6, 7. Factor 1 and 2 correlation is 0.23

Table 5.

Standardized parameter estimates for confirmatory factor analytic model

| Item | Null (all items) |

Factor 1 |

Factor 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1: engagement in Indian cultural behaviors | |||

| 2. How often native language spoken at home | 0.71 | 1.00 | – |

| 5. How often eat Indian food | 0.45 | 0.60 | – |

| 4. How often read Indian newspapers, magazines, books | 0.43 | 0.57 | – |

| 10. Generational status/Nativity | 0.39 | 0.52 | – |

| 9. Self-assessed cultural identity | 0.35 | 0.50 | – |

| 8. How often keep in contact with family and friends in India | 0.38 | 0.49 | – |

| Factor 2: social behaviors in U.S. | |||

| 1. English as primary language | 0.53 | – | 1.00 |

| 6. How open to child marrying outside cultural group | 0.36 | – | 0.72 |

| 7. Do you observe the traditional holidays important in your culture | 0.37 | – | 0.72 |

| 3. Language of interview | 0.34 | – | 0.55 |

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | ||

| Factor 1 | 1.00 | – | |

| Factor 2 | 0.080 | 1.00 | |

For the 2-factor model with correlated residuals, the goodness-of-fit df = 29, Chi square = 392.66, CFI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.7, indicating an acceptable fit. The correlated residuals for Factor 1 were home language preference and preference for Indian food (r = 0.41), frequency of contact with family/friends in India and generational status/nativity (r = 0.32), and preference for Indian media and frequency of contact with family/friends in India (r = 0.33); the correlated residuals for Factor 2 were English fluency and respondent choice of language in the interview (r = 0.35) and interview language and openness of one’s child marrying outside one’s cultural group (r = 0.33)

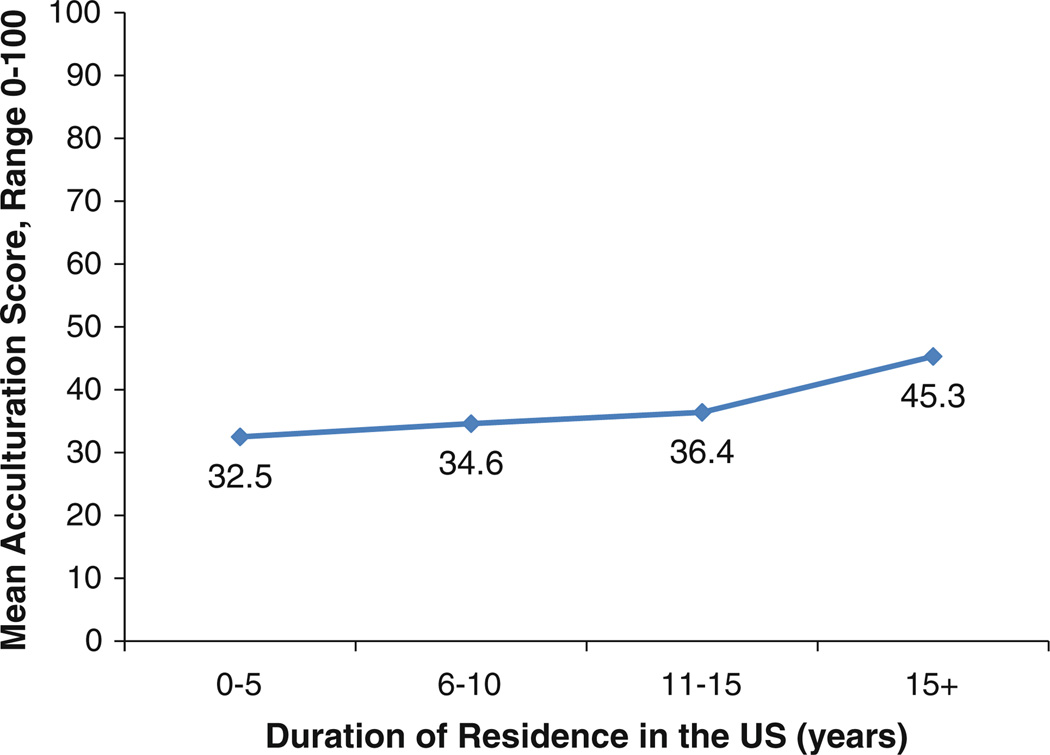

Despite some evidence of two potential domains underlying the 11 acculturation items, internal consistency reliability estimates were only 0.70 for engagement in Indian cultural behaviors and 0.59 for influence of Indian culture on social behaviors in the U.S. scales. Internal consistency reliability for the 11-item scale was 0.73 and item-scale correlations (corrected for item overlap with the total) ranged from 0.28–0.55 (Table 6). The 11-item acculturation scale had a mean of 39 and a standard deviation of 17, skewness was 0.45, and kurtosis of 3.04. The CFI for the one-factor model was 0.65 and the RMSEA was 0.10, indices suggesting suboptimal fit [16, 17]. Product-moment correlations of the scale with duration of residence in the U.S. was r = 0.37, with percentage of lifetime in the U.S. was r = 0.45, and with age at immigration was r = −0.34; p < 0.001 for correlations. There was a linear relationship between the acculturation scale score and duration of residence in the U.S. (Fig. 1).

Table 6.

Means, SD, and item-scale correlations for the acculturation scale core items treated as a single scale

| Item | Proportion endorsed by scale |

Item | Item-scale correlationa |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | M | SD | ||

| 1. English as primary language | 52 | 48 | – | – | – | 53 | 50 | 0.47 |

| 2. How often native language spoken at home | 66 | 18 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 17 | 30 | 0.55 |

| 3. Language of interview | 11 | 89 | – | – | – | 89 | 31 | 0.28 |

| 4. How often read Indian newspapers, magazines, books | 28 | 25 | 6 | 15 | 26 | 46 | 40 | 0.39 |

| 5. How often eat Indian food | 81 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 17 | 0.45 |

| 6. How open to child marrying outside cultural group | 9 | 9 | 17 | 28 | 36 | 68 | 32 | 0.34 |

| 7. Do you observe the traditional holidays important in your culture | 33 | 23 | 32 | 12 | – | 42 | 34 | 0.31 |

| 8. How often keep in contact with family and friends in India | 57 | 23 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 21 | 32 | 0.38 |

| 9. Self-assessed cultural identity | 24 | 16 | 50 | 6 | 4 | 38 | 26 | 0.36 |

| 10. Generational status/nativity | 86 | 14 | – | – | – | 13 | 33 | 0.40 |

| M | SD | Coefficient alpha | ||||||

| Scale | 39 | 17 | 0.73 | |||||

Item-scale correlations are corrected for overlap. The scale scores were the sum of the 10 items and were formed by linear transformations to a 0–100 distribution. For the 1-factor model, the goodness-of-fit df = 35, Chi square = 1,002.69, CFI = 0.65, RMSEA = 0.10, indicating a suboptimal fit

Fig. 1.

Mean acculturation score by duration of residence in the U.S. among Asian Indian immigrants. Higher acculturation score correlates with greater acculturation to American culture

Discussion

This study examined the associations of temporal measures with direct measures of acculturation among Asian Indians. While temporal measures may only partially capture acculturation, duration of residence or percentage of lifetime in the U.S. may be better proxies for acculturation than English preference or country of nativity for this population. Studies of Asians Indians cannot rely on language use as a proxy for acculturation because large majorities of Asian Indian immigrants are proficient English speakers [10, 21]. Additionally, Asian Indians who immigrate to the U.S. may have spent significant time in a Westernized country prior to immigration to the U.S., although we were not able to quantify that percentage in our sample except for nativity in a developed country [11].

Our study had several limitations. We developed a shorter acculturation scale than those used in the literature for Asians, with nonetheless acceptable reliability for group measurements, but not for individual level measurement [22]. Our scale was predicated on a unidirectional process of acculturation, or a linear relationship between moving from one cultural identity (e.g., ethnic identity) to the other (e.g., mainstream cultural identity) over time [5]. While the strength of this assimilation model of acculturation is its simplicity, this model has been criticized for not allowing ethnic minorities to have bicultural identities, despite the fact that many ethnic minorities describe themselves as such [7, 8, 23]. As previously mentioned, temporal measures of acculturation have also been criticized. However, proxy measurement and unidirectional scales continue to be widely used in immigrant health research because of the practical and financial challenges of using more in-depth psychometric scales and lack of a sound theoretical approach to acculturation-related health research [24, 25].

Despite these limitations, the 11-item scale captured the breadth of acculturation. The correlations of the scale were comparable to previously reported correlations of the 21-item Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation Scale (SL-ASIA) with duration of residence in the U.S. (r = 0.45 versus SL-ASIA, r = 0.56) and age at immigration (r = −0.34 vs. SL-ASIA, r = −0.49) [13].

Some have criticized the use of acculturation in health research given the conceptual and methodological difficulties with the construct, as well as its limitation as a modifiable factor in health promotion [26, 27]. Given these concerns, studies examining acculturation and healthcare should also account for modifiable access and utilization indicators, such as health insurance coverage, usual source of care, patient-provider communication, and socioeconomic status [27]. Specifically for Asian Indians who may be insular in their social activities and cultural practices, a greater understanding of these variables may be useful in explaining health outcomes in this growing minority population.

Acknowledgments

NB was supported by the National Research Service Award (T32 PE19001), and the American Heart Association— Pharmaceutical Roundtable Spina Outcomes Center (0875133N), Fellowships at the University of California, Los Angeles. RDH was supported in part by grants from the NIA (P30- AG021684) and the NIMHD (2P20MD000182). WJM was supported by the NHLBI—1P50HL105188-6094.

Contributor Information

Nazleen Bharmal, Division of General Internal Medicine and Health Services Research, Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, 911 Broxton Avenue, 2nd Floor, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1769, USA, nbharmal@mednet.ucla.edu.

Ron D. Hays, Division of General Internal Medicine and Health Services Research, Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA

William J. McCarthy, Department of Health Policy and Management, UCLA Jonathan and Karin Fielding School of Public Health, Los Angeles, CA, USA Department of Psychology, UCLA Jonathan and Karin Fielding School of Public Health, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

References

- 1.Martin P, Midgley E. Immigration: shaping and reshaping America. Population. 2003;58(2):1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Argeseanu Cunningham S, Ruben JD, Venkat Narayan KM. Health of foreign-born people in the United States: a review. Health Place. 2008;14(4):623–635. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salant T, Lauderdale DS. Measuring culture: a critical review of acculturation and health in Asian immigrant populations. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(1):71–90. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00300-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomson MD, Hoffman-Goetz L. Defining and measuring acculturation: a systematic review of public health studies with Hispanic populations in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(7):983–991. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon MM. Assimilation in American life: the role of race, religion, and national origins. New York: Oxford University Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berry J, Sam D. Acculturation and adaptation. In: Berry JW, Segal MH, Kagitcibasi C, editors. Handbook of cross-cultural psychology: social behavior and applications. Vol. 3. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 1997. pp. 291–326. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer EM. Dimensional accrual and dissociation: an introduction. In: Grace J, Kramer EM, editors. Communication, comparative cultures, and civilizations. Vol. 3. New York: Hampton; 2013. pp. 123–184. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer EM. Theoretical reflections on intercultural studies: preface. In: Croucher S, editor. Looking beyond the hijab. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abe-Kim J, Okazaki S, Goto SG. Unidimensional versus multidimensional approaches to the assessment of acculturation for Asian American populations. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2001;7(3):232–246. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.3.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mogelonsky M. Asian-Indian Americans. Am Demogr. 1995;17(8):32–39. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarthy WJ, Divan HA, Shah DB. Immigrant status and smoking. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1616. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1616. author reply 1616–1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung G, Ruth H, Kim B, Abreu J. Asian American multidimensional acculturation scale: development, factor analysis, reliability, and validity. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2004;10(1):66–80. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suinn RM, Ahuna C, Khoo G. The Suinn-Lew Asian self-identity acculturation scale: concurrent and factorial validation. Educ Psychol Meas. 1992;52(4):1041–1046. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnes PM, Adams PF, Powell-Griner E. Advance data from vital and health statistics; no 394. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2008. Health characteristics of the Asian adult population: United States, 2004–2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarthy WJ, Divan H, Shah D, et al. California Asian Indian Tobacco Survey: 2004. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Health Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lauderdale DS, Kestenbaum B. Asian American ethnic identification by surname. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2000;19(3):283–300. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hays RD, Revetto JP. Old and new MMPI-derived scales and the short-MAST as screening tools for alcohol disorder. Alcohol Alcohol. 1992;27(6):685–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hays R, Fayers P. Evaluating multi-item scales. In: Fayers PM, Hays RD, editors. Assessing quality of life in clinical trials: methods and practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams D, Mohammed S. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehta S. Relationship between acculturation and mental health for Asian Indian immigrants in the United States. Genet Soc Gen Psychol Monogr. 1998;124(1):61–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nunnally Jum C, Bernstein Ira H. Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen HH, von Eye A. The acculturation scale for Vietnamese adolescents (ASVA): a bidimensional perspective. Int J Behav Dev. 2002;26(3):202–213. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abraido-Lanza AF, Armbrister AN, Florez KR, Aguirre AN. Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(8):1342–1346. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker D. Conceptual parameters of acculturation within the Asian and pacific islander American populations: applications for nursing practice and research. Nurs Forum. 2011;46(2):83–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2011.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunt LM, Schneider S, Comer B. Should “acculturation” be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on US Hispanics. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(5):973–986. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pourat N, Kagawa-Singer M, Breen N, Sripipatana A. Access versus acculturation: identifying modifiable factors to promote cancer screening among Asian American women. Med Care. 2010;48(12):1088–1096. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f53542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]