Abstract

Objective

Altered subendothelial matrix composition regulates endothelial dysfunction and early atherosclerotic plaque formation. Hyperglycemia promotes endothelial matrix remodeling associated with multiple microvascular complications of diabetes, but a role for altered matrix composition in diabetic atherogenesis has not been described. Therefore, we sought to characterize the alterations in matrix composition during diabetic atherogenesis using both in vitro and in vivo model systems.

Methods and Results

Streptozotocin-induced diabetes in atherosclerosis-prone ApoE knockout mice promoted transitional matrix expression (fibronectin, thrombospondin-1) and deposition in intima of the aortic arch as determined by qRT-PCR array and immunohistochemistry. Early plaque formation occurs at discrete vascular sites exposed to disturbed blood flow patterns, whereas regions exposed to laminar flow are protected. Consistent with this pattern, hyperglycemia-induced transitional matrix deposition was restricted to regions of disturbed blood flow. Laminar flow significantly blunted high glucose-induced fibronectin expression (mRNA and protein) and fibronectin fibrillogenesis in endothelial cell culture models, whereas high glucose-induced fibronectin deposition was similar between disturbed flow and static conditions.

Conclusions

Taken together, these data demonstrate that flow patterns and hyperglycemia coordinately regulate subendothelial fibronectin deposition during early atherogenesis.

Keywords: shear stress, fibronectin, endothelial, hyperglycemia, atherosclerosis

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in developed countries. Patients with diabetes mellitus, a metabolic dysregulation of normal glucose homeostasis, show a 2 to 4-fold higher risk for cardiovascular events1 due to the enhanced formation of atherosclerotic plaques, a chronic inflammatory response to lipids that accumulate in the vessel wall2. Early atherogenesis is driven by local endothelial dysfunction culminating in lipoprotein deposition and monocyte recruitment2. This dysfunctional endothelium shows enhanced permeability and elevated expression of proinflammatory cell adhesion molecules (e.g. ICAM-1, VCAM-1) that mediate monocyte homing3, 4. In diabetic mouse models, chronic hyperglycemia is strongly associated with the formation of early plaques, termed fatty streaks5, and postmortem analysis of young patients and children with type 1 diabetes show enhanced fatty streak formation6, 7, suggesting that hyperglycemia promotes early plaque development. While recent clinical trials (ACCORD, ADVANCE) failed to find a significant effect of stringent glucose control on cardiovascular outcomes in diabetic patients8, 9, these data may result from the timing of glycemic control, as 10 year follow-ups of the DCCT and UKPDS trials found that tight glycemic control early following diagnosis of diabetes significantly decreases cardiovascular events10, 11.

Current data suggest that plaque formation is the product of both systemic risk factors and the local microenvironment. While most atherosclerotic risk factors are systemic throughout the circulation, atherosclerotic plaque formation is not ubiquitous but instead localizes to distinct vascular sites exposed to disturbed blood flow patterns such as vessel curvatures, branchpoints, and bifurcations12. Straight vascular segments, such as the common carotid, exposed to laminar blood flow are protected from plaque development, and cell culture models demonstrate that laminar flow reduces endothelial cell dysfunction by promoting nitric oxide production, reducing oxidant stress, and limiting proinflammatory gene expression12. Similar to hemodynamics, the composition of the subendothelial extracellular matrix provides important environmental cues that regulate endothelial cell function. During early atherogenesis, the endothelial basement membrane shows enhanced deposition of transitional matrix proteins (e.g. fibronectin) normally associated with tissue remodeling responses13. Fibronectin enhances endothelial cell dysfunction in multiple cell culture models; whereas endothelial cells on normal basement membrane proteins show reduced endothelial cell dysfunction13–16. Furthermore, blunting fibronectin deposition with a peptide inhibitor of fibronectin fibrillogenesis reduces endothelial inflammatory gene expression in mouse models of flow-induced vascular remodeling17, and deletion of plasma fibronectin reduces endothelial proinflammatory signaling, gene expression, and macrophage recruitment during early atherogenesis18.

Hyperglycemia affects matrix structure, abundance, and composition in a variety of systems19–22. Hyperglycemia-induced glycation of extracellular matrix proteins promotes matrix stiffening but reduces its adhesive capacity19, and excess production of extracellular matrix proteins drives tissue fibrosis during a number of diabetic complications20, 23. However, considerably less is known concerning altered matrix composition during diabetic complications. While transitional matrix deposition promotes microvascular dysfunction during diabetic retinopathy and nephropathy21, 22, a role for transitional matrix deposition in diabetic atherogenesis remains uninvestigated. Therefore, we sought to characterize whether hyperglycemia contributes to transitional matrix deposition during early atherogenesis.

2. Methods

2.1 Animal models and tissue collection

Animal protocols were approved by the LSU Health Sciences Center-Shreveport IACUC committee, and all animals were cared for according to the National Institute of Health guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. Male ApoE null mice on the C57Bl/6J genetic background (The Jackson Laboratory) were fed a standard chow diet. Between 6 and 8 weeks of age, mice were given either low-dose streptozotocin (Enzo Life Sciences, 50 mg·kg−1 in NaCitrate Buffer pH 4.5) or NaCitrate buffer injections for 5 consecutive days. Blood glucose levels were read using an AlphaTRAK glucometer (Abbott) until a reading of greater than 250 mg/dL was maintained for three consecutive days, at which point mice were considered diabetic. Glucose and weight were monitored weekly, and mice were euthanized after 4 or 6 weeks of diabetes by pneumothorax under isoflurane anesthesia. Multiple vascular beds were collected and analyzed, including the aortic arch, common carotid artery, innominate artery, and the carotid sinus. Tissue was fixed with formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5 µm sections. Plasma was analyzed for total cholesterol (Wako), HDL cholesterol (Wako) and triglycerides (Pointe Scientific) using commercially available ELISA kits. LDL cholesterol was calculated using the Friedewald equation (LDL = total cholesterol − HDL − (triglycerides/5)).

2.2 Quantitative Real Time-PCR (qRT-PCR)

qRT-PCR was performed as previously described24. For analysis of gene expression in vivo, aortas were harvested, cleaned of connective tissue, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then sonicated briefly at low power in TRIzol reagent. mRNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) per manufacturer’s instructions, and cDNA was synthesized using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Biorad). qRT-PCR was performed in a Biorad iCycler or BioRad CFX using Sybr Green Master mix (Biorad). Primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 1. Results were normalized to housekeeping genes (PPIA, Rpl13A, or GAPDH) using the 2ddCt method.

2.3 Immunohistochemistry

The avidin-biotin complex method was applied to deparaffinized sections. Antibodies used to visualize inflammation and matrix deposition included rabbit anti-fibronectin (Sigma, 1:500), mouse anti-TSP1 (Santa Cruz, 1:250) and rabbit anti-VCAM-1 (Santa Cruz, 1:400). Biotinylated goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse IgG (Vector Laboratories) were used as secondary antibodies, and detection was enhanced using the Vectastain Elite ABC kit (Vector Laboratories). Stains were developed using 3-3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Dako). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and visualized using an Olympus BX51 microscope and quantified using the Nikon Elements imaging software.

2.4 Endothelial Cell Culture and Shear Stress

Human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) were purchased from Lonza or Invitrogen at passage 3. Endothelial cells were cultured in either M199 or MCDB131 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, HyClone), ~0.08–0.17 mg/ml bovine hypothalamus extract (Pel-Freeze), 60 µg/ml heparin (Acros Organics), 100 U/ml penicillin (Hyclone), 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Hyclone), and 2 mM Glutamax (Gibco) and used between passages 6–10. Endothelial cells were plated at confluency in low serum media (1%) onto glass slides coated with basement membrane extract (BD Biosciences, 1:50 dilution). Slides were loaded onto a parallel plate flow chamber and subjected to either laminar (12 dynes/cm2) or oscillatory flow (±5 dynes/cm2, 1 Hz with 1 dyne/cm2 forward flow superimposed by a peristaltic pump to facilitate nutrient/waste exchange) for 18 hours as previously described13, 25. Cells plated onto slides and not subjected to flow were used as static controls. To test whether glucose levels affect the endothelial cell response to shear stress, cells were exposed to shear stress using media containing either low glucose levels (5 mM glucose, 20 mM mannose osmotic control) or high glucose levels (25 mM glucose) for the entire 18 hours of shear stress exposure. Static cells were switched to either low glucose or high glucose media for 18 hours to mimic the conditions in the flow chambers.

2.5 Fibronectin Fibrillogenesis

Fibronectin fibrillogenesis was analyzed as previously described26. Briefly, cells were extracted by sequential washes with 3% Triton X-100 and 2% sodium deoxycholate (DOC) buffers. The remaining DOC-insoluble matrix was then fixed in 4% formaldehyde and stained overnight with rabbit anti-fibronectin (1:500, Sigma) followed by 1 hour with Alexa488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen). Fibronectin staining was visualized on a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted fluorescent microscope, and images were captured at 60× oil objective using the Photometrics Coolsnap120 ES2 camera and the NIS Elements BR 3.00, SP5 imaging software. Fibronectin fibrils were quantified as percent area. For immunoblotting, cells were lysed in 1mL DOC buffer (2% sodium deoxycholate, 20 mM Tris-HCL, 2 mM PMSF, 2 mM iodoacetic acid (IAA), 2 mM EDTA, and 2 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM). DOC-insoluble material was isolated by centrifugation at 21K·g for 15 minutes. Supernatant was kept as the soluble fraction, and pelleted material was resuspended in solubilization buffer (2% SDS, 25 mM Tris-HCL, 2 mM PMSF, 2 mM IAA, 2 mM NEM, and 2 mM EDTA) and kept as the DOC-insoluble fraction. 2× Laemmli buffer was added and protein content was analyzed by Western blotting.

2.6 Statistical Analysis

Results shown are means +/− standard error. Statistical significance was determined by student’s T tests or Two-Way ANOVA using the GraphPad Prism software, and results were deemed statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1 Early changes in extracellular matrix gene expression in the diabetic aorta

To determine whether diabetes affects matrix composition during early atherogenesis, atherosclerosis-prone ApoE knockout mice were given multiple low dose injections of streptozotocin (50 mg/kg in citrate buffer) daily for 5 days to induce pancreatic β cell death. Mice injected with citrate buffer alone served as controls for these experiments. After confirmation of hyperglycemia, mice were maintained on standard chow diet for 4 to 6 weeks to allow for induction of early atherogenic changes in the vessel wall. Consistent with previous reports, diabetic ApoE knockout mice showed weight loss with significantly enhanced plasma glucose, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol levels compared to citrate buffer controls (Table 1). Plasma levels of HDL and triglycerides were not significantly different between diabetic and control animals.

Table 1. Streptozotocin-induced diabetes enhances blood glucose and plasma cholesterol levels.

Mouse weight and blood glucose levels were measured weekly and averaged for each mouse over the course of the 4 or 6 week study. Terminal blood draws were separated into plasma and analyzed for total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, or triglycerides using commercially available kits. LDL cholesterol was calculated using the Friedwalde equation. n = 4 mice per group.

| 4 week Citrate Buffer |

4 week Streptozotocin |

6 week Citrate Buffer |

6 week Streptozotocin |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | 26.0 ± 1.0 | 22.1 ± 0.8** | 26.7 ± 0.3 | 23.6 ± 0.9* |

| Blood Glucose | 169.4 ± 7.3 | 488.5 ± 26.8*** | 185.4 ± 6.8 | 528.9 ± 52.2*** |

| Total Cholesterol | 407.3 ± 114.3 | 1093.0 ± 38.4* | 390.1 ± 25.5 | 990.5 ± 177.8* |

| HDL | 58.2 ± 9.9 | 105.6 ± 55.2 | 40.9 ± 6.8 | 71.1 ± 40.9 |

| LDL | 336.0 ± 124.6 | 944.0 ± 22.9* | 339.0 ± 24.5 | 900.6 ± 159.4* |

| Triglycerides | 65.8 ± 18.5 | 217.5 ± 135.3 | 51.2 ± 4.5 | 94.2 ± 15.3 |

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001 compared to citrate buffer controls.

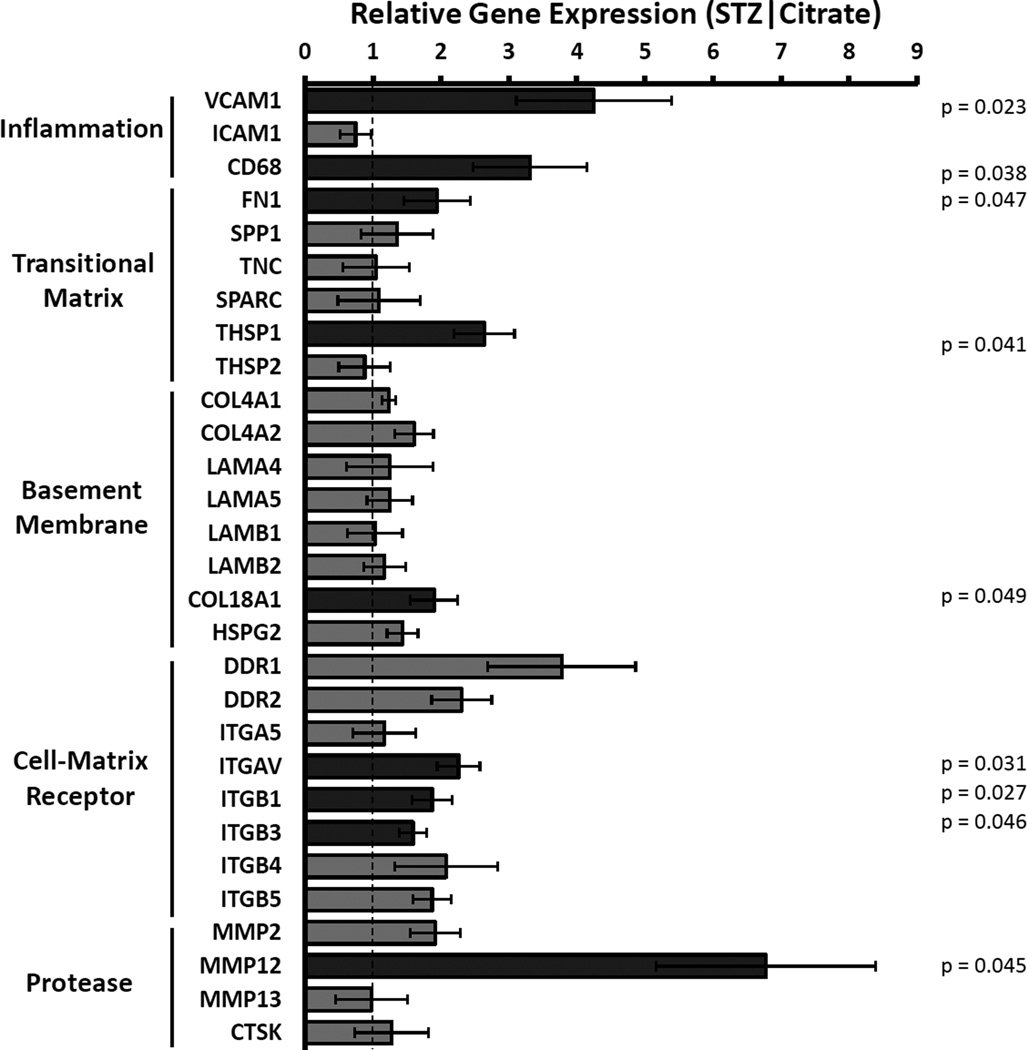

Aortic arches from 6 week control or diabetic mice were first analyzed by qRT-PCR for altered mRNA expression of multiple extracellular matrix-associated genes using a custom array. Consistent with early diabetic atherogenesis, both VCAM-1 and the monocyte/macrophage marker CD68 showed significantly enhanced expression in the diabetic vessels (Figure 1). While the subendothelial basement membrane proteins collagen IV (COL4A1, COL4A2), laminin-411 (LAMA4), and laminin-511 (LAMA5, LAMB1, LAMB2) did not show significantly altered expression in diabetic mice27, expression of the transitional matrix proteins fibronectin (FN1) and thrombospondin-1 (THSP1) was markedly increased (Figure 1). Interestingly, diabetic vessels also showed enhanced expression of pro-atherogenic elastase MMP-12 (Figure 1)28, as well as several transitional extracellular matrix receptors, including αv and β3 integrins.

Figure 1. Altered expression of extracellular matrix genes in early diabetic atherogenesis.

ApoE null mice at 6 to 8 weeks of age received either low-dose streptozotocin (50 mg·kg−1) or Na-Citrate buffer injections. After 6 weeks of diabetes, the aorta was harvested and analyzed by qRT-PCR for gene expression of inflammatory and matrix-related genes. Gene expression was normalized to housekeeping genes and to nondiabetic controls. n = 4 mice per condition. * p < 0.05.

3.2 Altered matrix expression in the diabetic aorta localizes to sites of disturbed blood flow

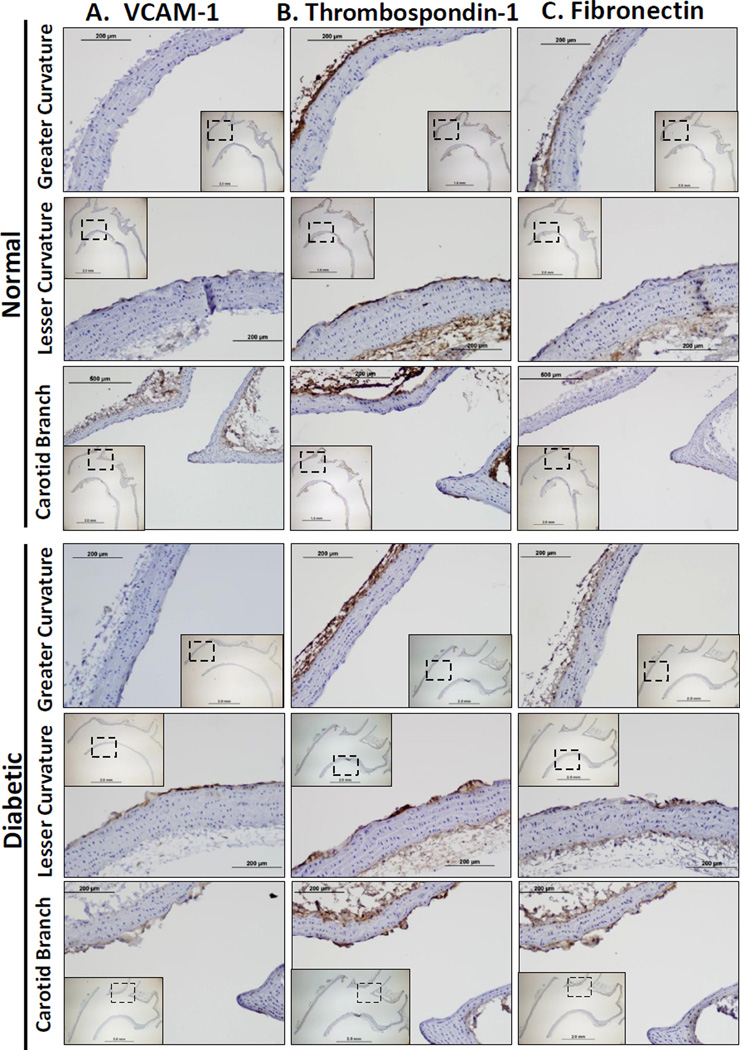

Hyperglycemia may affect extracellular matrix production by multiple cell types, including the endothelium, macrophages, smooth muscle cells, and adventitial fibroblasts. To determine which cells in the diabetic vessels show altered fibronectin and thrombospondin-1 expression, transverse sections of the aortic arch were stained for VCAM-1 (Figure 2A), thrombospondin-1 (Figure 2B), and fibronectin (Figure 2C) by immunohistochemistry. VCAM-1 expression and fibronectin deposition localized specifically to the intima in known atherosclerosis prone regions, including the lesser curvature of the aortic arch as well as the carotid branchpoints (Figure 2A/C). In contrast, the greater curvature of the aortic arch did not stain positive for fibronectin, suggesting that the distinctive flow patterns in these regions regulate fibronectin deposition. The medial and adventitial layers showed minimal fibronectin expression and no observable difference between control and diabetic tissue. Thrombospondin-1 deposition was apparent in the adventitia and in the atherosclerosis-prone intima; however thrombospondin-1 levels did not appear to differ between normal and diabetic animals (Figure 2B). The presence of intimal thrombospondin-1 in control mice suggests that the altered flow profiles are sufficient to drive thrombospondin-1 expression, whereas fibronectin expression requires a second atherogenic stimulus (ex. hyperglycemia).

Figure 2. Hyperglycemia stimulates fibronectin deposition at sites of disturbed flow in the aortic arch.

The aortic arch was collected from diabetic (6 weeks) and nondiabetic ApoE knockout mice and stained for A) VCAM-1, B) thrombospondin-1, or C) fibronectin deposition. Regions exposed to either laminar flow (greater curvature) or disturbed flow (lesser curvature, carotid branch point) are shown at 20× magnification with 4× magnification inserts of the entire artery. n = 4 – 7 mice per group.

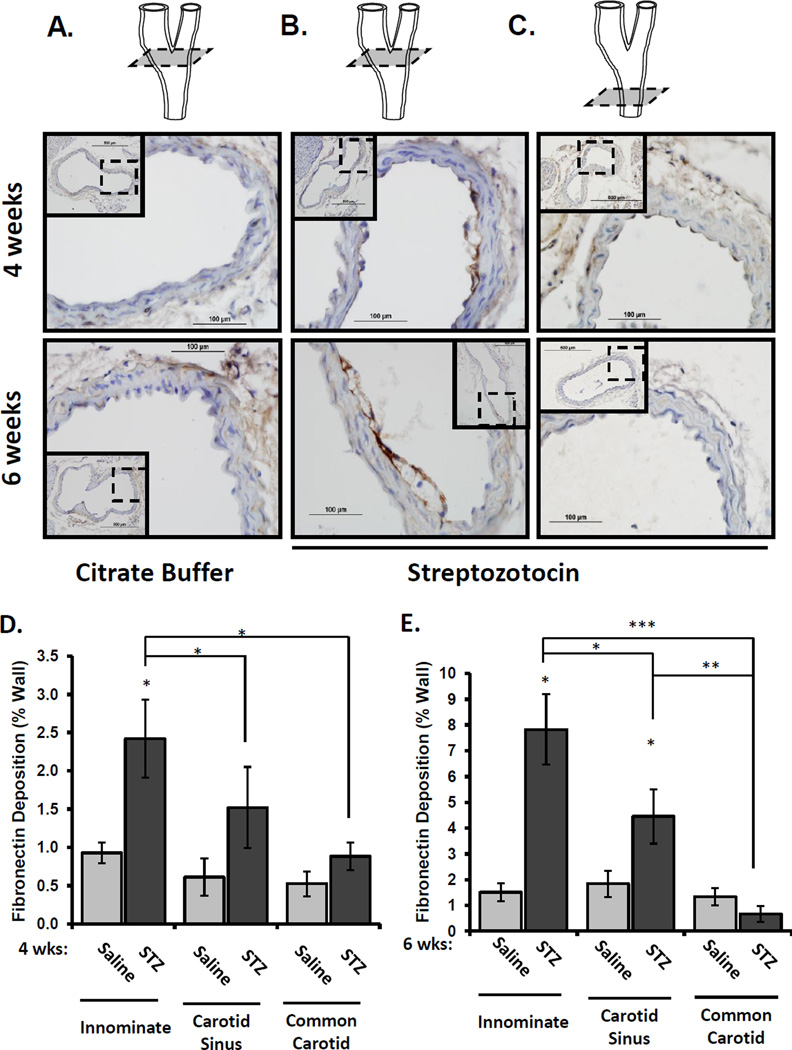

3.3 Fibronectin deposition in diabetic mice localizes to disturbed flow regions in the innominate and carotid arteries

To verify that flow patterns affect hyperglycemia-induced fibronectin deposition, we measured fibronectin staining in vascular regions with more uniform flow profiles, including the laminar flow-associated common carotid and the disturbed flow-associated innominate artery and carotid sinus. Fibronectin staining was apparent in the endothelial cell layer 4 to 6 weeks after induction of hyperglycemia (Figure 3A/B), and this staining pattern correlated with areas of early fatty streak development. The common carotid artery did not show significant fibronectin deposition in the diabetic animals despite its exposure to the same level of hyperglycemia (Figure 3C). Quantification of fibronectin deposition at these sites showed a statistically significant increase in whole vessel fibronectin staining in the innominate artery at both 4 weeks and 6 weeks (Figure 3D/E), whereas fibronectin deposition in the carotid sinus was not significantly different between control and diabetic mice until the 6 week time point. Taken together, these data suggest that flow patterns regulate the local susceptibility of the subendothelial matrix to hyperglycemia-induced fibronectin deposition.

Figure 3. Hyperglycemia stimulates fibronectin deposition at sites of disturbed flow in the carotid artery.

The carotid sinus and common carotid was collected from diabetic (4 and 6 weeks) and nondiabetic ApoE knockout mice and stained for fibronectin deposition. Representative images from A) citrate-buffer treated (nondiabetic) carotid sinus, B) STZ-treated (diabetic) carotid sinus, and C) STZ-treated common carotid are shown. Images are at 40× magnification and the insets show the 10× magnification of the entire artery. (D,E) Fibronectin staining at different vascular sites (innominate, carotid sinus, or common carotid) was quantified using Nikon Elements software. n =4–7 mice per group, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

3.4 Laminar flow prevents hyperglycemia-induced fibronectin expression and deposition in cell culture models

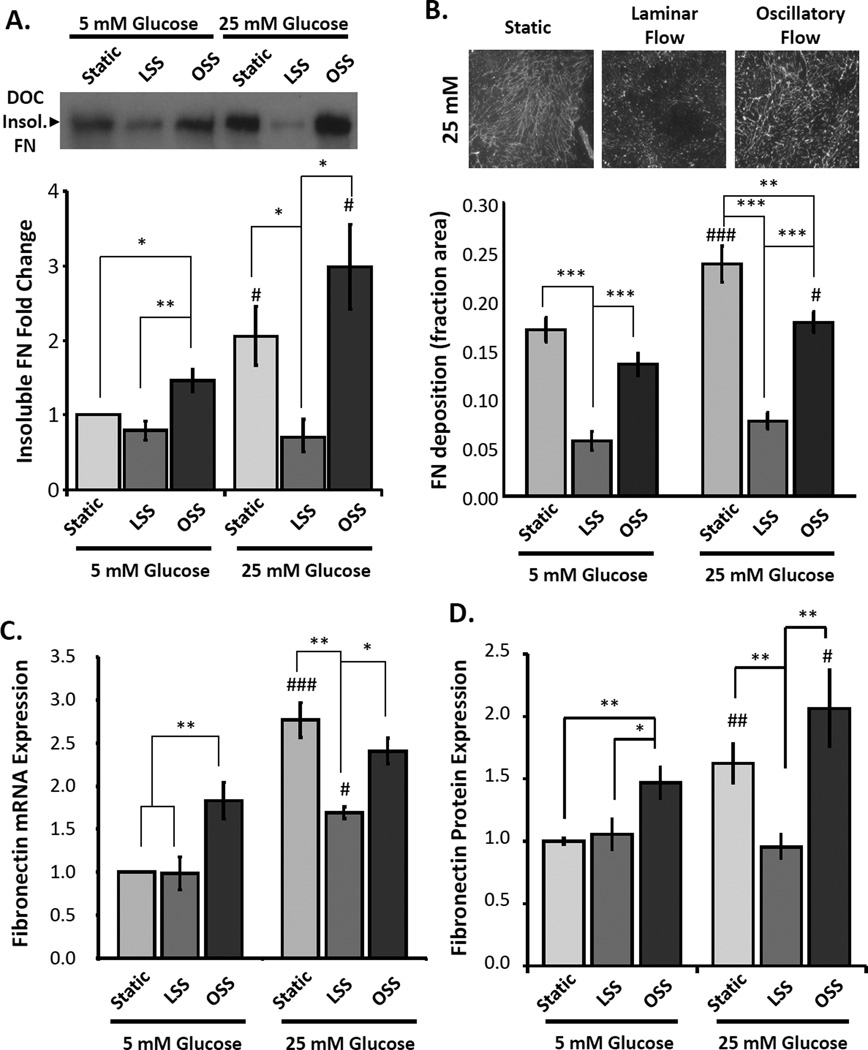

To determine how flow patterns regulate high glucose-induced fibronectin deposition, we mimicked these differing conditions using human aortic endothelial cells in an in vitro parallel plate flow chamber. Endothelial cells plated on basement membrane proteins were exposed to static conditions, laminar flow, or oscillatory flow (model of disturbed flow) for 18 hours in the presence of low glucose (5 mM) or high glucose media (25 mM). The extracellular matrix was then purified by DOC extraction and quantified by Western blotting and immunocytochemistry. Consistent with other model systems, high glucose conditions enhanced fibronectin deposition in endothelial cells under static conditions (Figure 4A). Exposure to oscillatory flow did not significantly affect glucose-induced fibronectin deposition, whereas laminar shear stress potently inhibited fibronectin matrix deposition under high glucose conditions. To confirm this result, we visualized fibronectin fibrils by immunocytochemistry and quantified the fibronectin positive area.

Figure 4. Laminar flow significantly inhibits hyperglycemia-induced FN deposition in vitro.

HAECs exposed to laminar shear stress (LSS), oscillatory shear stress (OSS), or static conditions for 18 hours in the presence of either 5 mM or 25 mM glucose. Mannose was added to the 5 mM glucose treatments to control for osmolarity. Cells were extracted using Triton X-100 and deoxycholic acid (DOC), and (A) the DOC-insoluble and soluble fractions were collected and the presence of fibronectin in the endothelial matrix was quantified by Western blotting. n = 4–5. (B) Alternatively, the underlying matrix was fluorescently stained for fibronectin and quantified as percent positive area. At least 10 random images were taken for each treatment. n = 3. C) Fibronectin mRNA expression was determined by qRT-PCR and normalized to β2-microglobin mRNA levels. n = 3–6. (D) Total cellular fibronectin protein expression was determined by Western blotting cell lysates. n =4–5. # p < 0.05 and ### p < 0.001 compared to low glucose controls. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 compared to static controls.

While endothelial cells produced extensive fibronectin fibrils under static and oscillatory flow conditions, exposure to laminar flow was sufficient to significantly blunt fibronectin matrix deposition (Figure 4B). We next tested whether flow patterns similarly regulate endothelial fibronectin expression. Exposure to high glucose media resulted in a significant increase in fibronectin mRNA (Figure 4C) and protein expression (Figure 4D). However, laminar flow was sufficient to completely inhibit the enhanced fibronectin expression under high glucose conditions (Figure 4C/D). While disturbed flow alone enhanced fibronectin expression in our cell culture model under low glucose conditions, high glucose-induced fibronectin expression was not differentially affected under static or disturbed flow conditions. Taken together, these data suggest that hyperglycemiainduced fibronectin deposition is restricted to regions of disturbed flow due to the inhibitory effect of laminar flow on endothelial fibronectin expression and deposition.

4. Discussion

Fibronectin deposition into the subendothelial matrix promotes endothelial cell dysfunction with reduced nitric oxide production and enhanced proinflammatory gene expression13, 16–18. In the current study, we demonstrate that experimental diabetes in ApoE knockout mice accelerates fibronectin deposition into the subendothelial cell matrix in a site-specific manner. The transitional matrix proteins fibronectin and thrombospondin-1 both show enhanced mRNA expression in the aortic arch of diabetic mice. While control mice exhibit minimal fibronectin expression, diabetic mice show significantly enhanced fibronectin expression specifically at sites of disturbed blood flow (lesser curvature of arch, carotid sinus). In contrast, thrombospondin-1 protein expression at sites of disturbed flow is apparent even in non-diabetic animals and did not appear to be greatly influenced by diabetes. Vascular regions exposed to laminar flow (greater curvature of arch, common carotid) are protected from diabetes-induced fibronectin deposition, and cell culture models demonstrate that laminar flow significantly inhibits both fibronectin expression and deposition.

Vascular matrix remodeling, both through altered composition and structure, contributes to a number of pathological complications of diabetes. Data presented herein suggest that streptozotocin-induced diabetes in ApoE knockout mice is sufficient to induce endothelial transitional matrix expression. However, the induction of diabetes in this model causes a significant increase in plasma lipid levels29 (Table 1), making it difficult to separate whether the effects seen are due to hyperglycemia or dyslipidemia. However, several lines of evidence including our cell culture studies suggest hyperglycemia drives diabetic matrix remodeling. Hyperglycemia induces thickening of the capillary basement membrane during diabetic retinopathy and nephropathy30, and these diabetic basement membranes show enhanced fibronectin deposition as well.

Tight glycemic control reduces basement membrane thickening and fibronectin expression in retinal and renal capillaries31, suggesting that hyperglycemia drives these changes in matrix composition and structure. Preventing fibronectin expression using locally applied fibronectin siRNA limits microvascular complications of diabetes by reducing basement membrane thickening, acellular capillaries, and pericyte loss21, 22. Fibronectin deposition similarly contributes to early atherogenic changes in large arteries, as mice lacking the EDA splice variant of fibronectin or showing conditional deletion of plasma fibronectin have reduced atherosclerosis with diminished proinflammatory gene expression and macrophage recruitment18, 32. Interestingly, hyperglycemia induced fibronectin expression can be sustained for weeks after restoration of normoglycemia33, 34, suggesting that this altered matrix composition may provide a form a tissue memory, allowing alterations in the tissue matrix to affect the resultant cellular function long after the inciting stimulus has been removed.

Shear stress and hyperglycemia play complex roles in regulation of endothelial cell dysfunction, with each stimulus affecting the endothelial cell response to the other. While laminar and oscillatory shear stress do not precisely match the flow profiles seen in atherosclerosis-protected and prone regions, respectively, they produce well characterized phenotypic changes to the endothelium that match that seen in those regions in vivo12. Atherosclerosis in diabetic patients is more diffuse than in nondiabetics and involves more vessels35, leading several groups to postulate that hyperglycemia reduces the protective properties of laminar shear stress. Laminar shear stress limits endothelial cell dysfunction in part by promoting eNOS-dependent nitric oxide production16, and high glucose conditions can blunt shear stress-induced nitric oxide production due to enhanced nitric oxide scavenging3, reduced eNOS expression36, 37, and increased O-GlcNAc modification of eNOS38. While these data suggest hyperglycemia can reduce the protective effects of laminar flow, the diffuse atherosclerosis observed in diabetic patients may result from greater plaque burden at multiple sites of disturbed flow rather than mislocalization of atherosclerosis to sites of laminar flow. Consistent with this interpretation, animal models of diabetic atherosclerosis have found that atherosclerosis arises predominantly at sites of disturbed flow29, 39. Furthermore, laminar flow can prevent hyperglycemia-induced endothelial cell dysfunction, as laminar flow reduces inflammation induced by advanced glycation end products and high glucose media40, 41. Our data support the latter model as we observed early atherogenic matrix remodeling only at sites of disturbed flow and dominant inhibition of high glucose-induced fibronectin deposition by laminar flow.

While our cell culture models suggest that site-specific fibronectin deposition occurs due to the protective effects of laminar flow, other groups have shown that disturbed flow is sufficient to drive fibronectin matrix assembly. Fibronectin expression can be driven by the proinflammatory transcription factor NF-κB, and disturbed flow can induce PECAM-1 dependent NF-κB activation to promote fibronectin expression42. In low glucose conditions, our data is in agreement with these studies, since disturbed flow promoted a slight but significant increase in fibronectin expression and deposition compared to static conditions (Figure 4). However, our data suggest that macrovascular fibronectin deposition is minimal in nondiabetic mice (Figures 2–3) and did not differ substantially between laminar flow and disturbed flow regions (Figure 3). Alternatively, our data suggest that the deposition of fibronectin in response to systemic hyperglycemia is directed to sites of disturbed flow due to a dominant inhibitory effect of laminar flow. Consistent with this model, atheroprotective flow profiles derived from the common carotid artery were shown to significantly reduce fibronectin deposition, whereas atheroprone flow profiles derived from the carotid sinus did not differ significantly from static conditions43. Taken together, these data suggest that fibronectin deposition localizes specifically to sites of disturbed flow in atherosclerosis-prone mice due to an inhibitory effect of laminar flow on fibronectin expression and deposition.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Diabetes promotes transitional matrix deposition in atherosclerosis-prone arteries

Fibronectin deposition is limited to regions of disturbed blood flow

Diabetes does not induced matrix remodeling in regions exposed to laminar flow

Laminar flow blunts hyperglycemia-induced matrix remodeling in endothelial cells

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health [R01 HL098435 to A.W.O]; the American Diabetes Association [Junior Faculty Award 1-10-JF-39 to A.W.O]; and the Louisiana Board of Regents Superior Toxicology Fellowship [LEQSF (2008-13)-FG-20 to A.Y.J.].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fox CS, Coady S, Sorlie PD, Levy D, Meigs JB, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Wilson PW, Savage PJ. Trends in cardiovascular complications of diabetes. JAMA. 2004;292:2495–2499. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.20.2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: from pathophysiology to practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2129–2138. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Funk SD, Yurdagul A, Jr, Orr AW. Hyperglycemia and endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis: lessons from type 1 diabetes. Int J Vasc Med. 2012;2012:569654. doi: 10.1155/2012/569654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI, Nourshargh S. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:678–689. doi: 10.1038/nri2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Renard CB, Kramer F, Johansson F, Lamharzi N, Tannock LR, von Herrath MG, Chait A, Bornfeldt KE. Diabetes and diabetes-associated lipid abnormalities have distinct effects on initiation and progression of atherosclerotic lesions. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:659–668. doi: 10.1172/JCI17867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGill HC, Jr, McMahan CA, Zieske AW, Malcom GT, Tracy RE, Strong JP. Effects of nonlipid risk factors on atherosclerosis in youth with a favorable lipoprotein profile. Circulation. 2001;103:1546–1550. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.11.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jarvisalo MJ, Putto-Laurila A, Jartti L, Lehtimaki T, Solakivi T, Ronnemaa T, Raitakari OT. Carotid artery intima-media thickness in children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:493–498. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, Goff DC, Jr, Bigger JT, Buse JB, Cushman WC, Genuth S, Ismail-Beigi F, Grimm RH, Jr, Probstfield JL, Simons-Morton DG, Friedewald WT. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2545–2559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, Neal B, Billot L, Woodward M, Marre M, Cooper M, Glasziou P, Grobbee D, Hamet P, Harrap S, Heller S, Liu L, Mancia G, Mogensen CE, Pan C, Poulter N, Rodgers A, Williams B, Bompoint S, de Galan BE, Joshi R, Travert F. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2560–2572. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1577–1589. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, Genuth SM, Lachin JM, Orchard TJ, Raskin P, Zinman B. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2643–2653. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahn C, Schwartz MA. Mechanotransduction in vascular physiology and atherogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:53–62. doi: 10.1038/nrm2596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orr AW, Sanders JM, Bevard M, Coleman E, Sarembock IJ, Schwartz MA. The subendothelial extracellular matrix modulates NF-kappaB activation by flow: a potential role in atherosclerosis. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:191–202. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200410073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Funk SD, Yurdagul A, Jr, Green JM, Jhaveri KA, Schwartz MA, Orr AW. Matrix-specific protein kinase A signaling regulates p21-activated kinase activation by flow in endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2010;106:1394–1403. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.210286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orr AW, Stockton R, Simmers MB, Sanders JM, Sarembock IJ, Blackman BR, Schwartz MA. Matrix-specific p21-activated kinase activation regulates vascular permeability in atherogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:719–727. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yurdagul A, Jr, Chen J, Funk SD, Albert P, Kevil CG, Orr AW. Altered nitric oxide production mediates matrix-specific PAK2 and NF-kappaB activation by flow. Mol Biol Cell. 2012 doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-07-0513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiang HY, Korshunov VA, Serour A, Shi F, Sottile J. Fibronectin is an important regulator of flow-induced vascular remodeling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1074–1079. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.181081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rohwedder I, Montanez E, Beckmann K, Bengtsson E, Duner P, Nilsson J, Soehnlein O, Fassler R. Plasma fibronectin deficiency impedes atherosclerosis progression and fibrous cap formation. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4:564–576. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201200237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diez J. Arterial stiffness and extracellular matrix. Adv Cardiol. 2007;44:76–95. doi: 10.1159/000096722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Law B, Fowlkes V, Goldsmith JG, Carver W, Goldsmith EC. Diabetes-induced alterations in the extracellular matrix and their impact on myocardial function. Microsc Microanal. 2012;18:22–34. doi: 10.1017/S1431927611012256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roy S, Nasser S, Yee M, Graves DT. A long-term siRNA strategy regulates fibronectin overexpression and improves vascular lesions in retinas of diabetic rats. Mol Vis. 2011;17:3166–3174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roy S, Sato T, Paryani G, Kao R. Downregulation of fibronectin overexpression reduces basement membrane thickening and vascular lesions in retinas of galactose-fed rats. Diabetes. 2003;52:1229–1234. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.5.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolset SO, Reinholt FP, Jenssen T. Diabetic nephropathy and extracellular matrix. J Histochem Cytochem. 2012;60:976–986. doi: 10.1369/0022155412465073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Funk SD, Yurdagul A, Jr, Albert P, Traylor JG, Jr, Jin L, Chen J, Orr AW. EphA2 activation promotes the endothelial cell inflammatory response: a potential role in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:686–695. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.242792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orr AW, Hahn C, Blackman BR, Schwartz MA. p21-activated kinase signaling regulates oxidant-dependent NF-kappa B activation by flow. Circ Res. 2008;103:671–679. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orr AW, Ginsberg MH, Shattil SJ, Deckmyn H, Schwartz MA. Matrix-specific suppression of integrin activation in shear stress signaling. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:4686–4697. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-04-0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hallmann R, Horn N, Selg M, Wendler O, Pausch F, Sorokin LM. Expression and function of laminins in the embryonic and mature vasculature. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:979–1000. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00014.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson JL, Devel L, Czarny B, George SJ, Jackson CL, Rogakos V, Beau F, Yiotakis A, Newby AC, Dive V. A selective matrix metalloproteinase-12 inhibitor retards atherosclerotic plaque development in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:528–535. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.219147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park L, Raman KG, Lee KJ, Lu Y, Ferran LJ, Jr, Chow WS, Stern D, Schmidt AM. Suppression of accelerated diabetic atherosclerosis by the soluble receptor for advanced glycation endproducts. Nat Med. 1998;4:1025–1031. doi: 10.1038/2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roy S, Ha J, Trudeau K, Beglova E. Vascular basement membrane thickening in diabetic retinopathy. Curr Eye Res. 2010;35:1045–1056. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2010.514659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cherian S, Roy S, Pinheiro A. Tight glycemic control regulates fibronectin expression and basement membrane thickening in retinal and glomerular capillaries of diabetic rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:943–949. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan MH, Sun Z, Opitz SL, Schmidt TE, Peters JH, George EL. Deletion of the Alternatively Spliced Fibronectin EIIIA Domain in Mice Reduces Atherosclerosis. Blood. 2004 doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roy S, Sala R, Cagliero E, Lorenzi M. Overexpression of fibronectin induced by diabetes or high glucose: phenomenon with a memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:404–408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ihnat MA, Thorpe JE, Kamat CD, Szabo C, Green DE, Warnke LA, Lacza Z, Cselenyak A, Ross K, Shakir S, Piconi L, Kaltreider RC, Ceriello A. Reactive oxygen species mediate a cellular 'memory' of high glucose stress signalling. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1523–1531. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0684-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vigorita VJ, Moore GW, Hutchins GM. Absence of correlation between coronary arterial atherosclerosis and severity or duration of diabetes mellitus of adult onset. Am J Cardiol. 1980;46:535–542. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(80)90500-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woo CH, Shishido T, McClain C, Lim JH, Li JD, Yang J, Yan C, Abe J. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 SUMOylation antagonizes shear stress-induced antiinflammatory response and endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression in endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2008;102:538–545. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.156877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Connell P, Walshe T, Ferguson G, Gao W, O'Brien C, Cahill PA. Elevated glucose attenuates agonist- and flow-stimulated endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity in microvascular retinal endothelial cells. Endothelium. 2007;14:17–24. doi: 10.1080/10623320601177213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Musicki B, Kramer MF, Becker RE, Burnett AL. Inactivation of phosphorylated endothelial nitric oxide synthase (Ser-1177) by O-GlcNAc in diabetes-associated erectile dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11870–11875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502488102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jun JY, Ma Z, Segar L. Spontaneously diabetic Ins2(+/Akita):apoE-deficient mice exhibit exaggerated hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E145–E154. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00034.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeVerse JS, Bailey KA, Jackson KN, Passerini AG. Shear stress modulates RAGE-mediated inflammation in a model of diabetes-induced metabolic stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H2498–H2508. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00869.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohan S, Hamuro M, Koyoma K, Sorescu GP, Jo H, Natarajan M. High glucose induced NF-kappaB DNA-binding activity in HAEC is maintained under low shear stress but inhibited under high shear stress: role of nitric oxide. Atherosclerosis. 2003;171:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feaver RE, Gelfand BD, Wang C, Schwartz MA, Blackman BR. Atheroprone hemodynamics regulate fibronectin deposition to create positive feedback that sustains endothelial inflammation. Circ Res. 2010;106:1703–1711. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.216283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gelfand BD, Meller J, Pryor AW, Kahn M, Bortz PD, Wamhoff BR, Blackman BR. Hemodynamic activation of beta-catenin and T-cell-specific transcription factor signaling in vascular endothelium regulates fibronectin expression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1625–1633. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.227827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.