Abstract

Catha edulis (khat) is a plant grown commonly in the horn of Africa. The leaves of khat are chewed by the people for its stimulant action. Its young buds and tender leaves are chewed to attain a state of euphoria and stimulation. Khat is an evergreen shrub, which is cultivated as a bush or small tree. The leaves have an aromatic odor. The taste is astringent and slightly sweet. The plant is seedless and hardy, growing in a variety of climates and soils.

Many different compounds are found in khat including alkaloids, terpenoids, flavonoids, sterols, glycosides, tannins, amino acids, vitamins and minerals. The phenylalkylamines and the cathedulins are the major alkaloids which are structurally related to amphetamine.

The major effects of khat include those on the gastro-intestinal system and on the nervous system. Constipation, urine retention and acute cardiovascular effects may be regarded as autonomic (peripheral) nervous system effects; increased alertness, dependence, tolerance and psychiatric symptoms as effects on the central nervous system. The main toxic effects include increased blood pressure, tachycardia, insomnia, anorexia, constipation, general malaise, irritability, migraine and impaired sexual potency in men.

Databases such as Pubmed, Medline, Hinary, Google search, Cochrane and Embase were systematically searched for literature on the different aspects of khat to summarize chemistry, pharmacology, toxicology of khat (Catha edulis Forsk).

Keywords: Chemistry, Pharmacology, Toxicology, Khat, Effect, Cathinone

Introduction

Khat is a natural stimulant from the Catha edulis plant that is cultivated in the Republic of Yemen and most of the countries of East Africa. Its young buds and tender leaves are chewed to attain a state of euphoria and stimulation.1 Khat is an evergreen shrub, which is cultivated as a bush or small tree. The leaves have an aromatic odor. The taste is astringent and slightly sweet. The plant is seedless and hardy, growing in a variety of climates and soils. Khat can be grown in droughts where other crops have failed and also at high altitudes. Khat is harvested throughout the year. Planting is staggered to obtain a continuous supply.2 There is fairly extensive literature on the potential adverse effects of habitual use of khat on mental, physical and social well-being.

Reasons for chewing khat and behaviors associated with the ritual of khat chewing

The vast majority of those ingesting khat do so by chewing. Only a small number ingest it by making a drink from dried leaves, or even more rarely, by smoking dried leaves. The chewer fills his or her mouth with leaves and stalks, and then chews slowly and intermittently to release the active components in the juice, which is then swallowed with saliva. The plant material is chewed into a ball, which is kept for a while in the cheek, causing a characteristic bulge.3 Khat chewing usually takes place in groups in a social setting. Only a minority frequently chew alone. A session may last for several hours. During this time chewers drink copious amounts of non-alcoholic fluids such as cola, tea and cold water. In a khat chewing session, initially there is an atmosphere of cheerfulness, optimism and a general sense of well-being. After about 2 hours, tension, emotional instability and irritability begin to appear, later leading to feelings of low mood and sluggishness. Chewers tend to leave the session feeling depleted.

Chewing khat is both a social and a culture-based activity. It is said to enhance social interaction, playing a role in ceremonies such as weddings. In Yemen, Muslims are the most avid chewers. Some believe that chewing facilitates contact with Allah when praying. However, many Christians and Yemenite Jews in Israel also chew khat. Khat is a stimulant and it is used to improve performance, stay alert and to increase work capacity.1,4 Workers on night shifts use it to stay awake and postpone fatigue. Students have chewed khat in an attempt to improve mental performance before exams. Yemeni khat chewers believe that khat is beneficial for minor ailments such as headaches, colds, body pains, fevers, arthritis and also depression.5

Chemistry

Khat contains more than forty alkaloids, glycosides, tannins, amino acids, vitamins and minerals.6 The environmental and climate conditions determine the chemical profile of khat leaves. In the Yemen Arab Republic, about 44 different types of khat exist originating from different geographic areas of the country.7,8

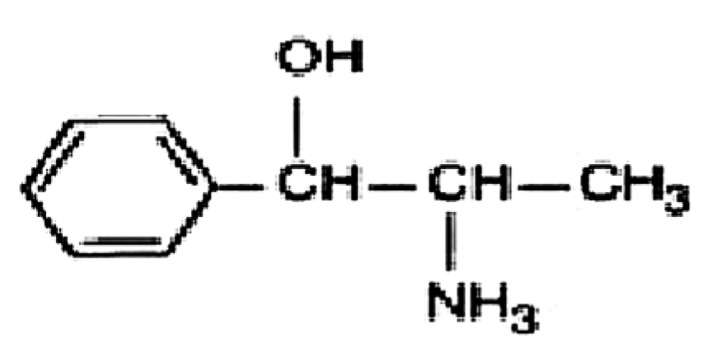

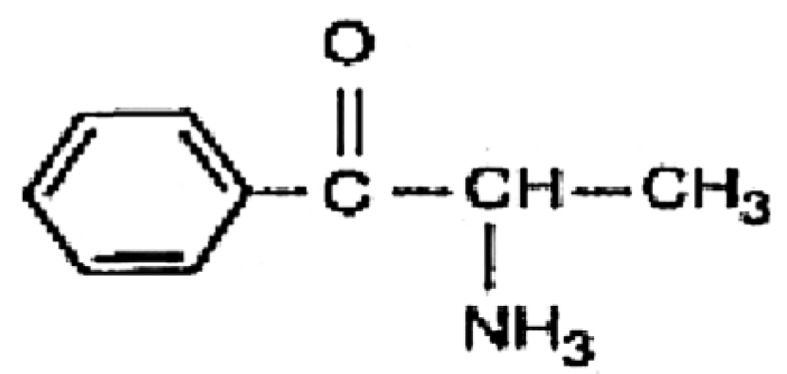

Many different compounds are found in khat including alkaloids, terpenoids, flavonoids, sterols, glycosides, tannins, amino acids, vitamins and minerals.9-11 The phenylalkylamines and the cathedulins are the major alkaloids. The cathedulins are based on a polyhydroxylated sesquiterpene skeleton and are basically polyesters of euonyminol. Recently, 62 different cathedulins from fresh khat leaves were characterized.12 The khat phenylalkylamines comprise cathinone [S-(-)-cathinone], and the two diastereoisomers cathine [1S, 2S-(+)-norpseudoephedrine or (+)-norpseudoephedrine] and norephedrine [1R,2S-(-)-norephedrine]. These compounds are structurally related to amphetamine and noradrenaline. The plant contains the (-)-enantiomer of cathinone only.11 Thus, the naturally occurring S-(-)-cathinone has the same absolute configuration as S-(+)-amphetamine (Figure 1). Cathinone is mainly found in the young leaves and shoots. During maturation, cathinone is metabolized to cathine [(+)-norpseudoephedrine] and (-)-norephedrine (Figure 2). The leaves contain [(+)-norpseudoephedrine] and (-)-norephedrine in a ratio of approximately 4:1.11 Other phenylalkylamine alkaloids found in khat leaves are the phenylpentenylamines merucathinone, pseudomerucathine and merucathine. These compounds seem to contribute less to the stimulant effects of khat.10,13,14

Figure 1.

Chemical Structures of cathinone

Figure 2.

Chemical Structures of cathine

Cathinone is unstable and undergoes decomposition reactions after harvesting and during drying or extraction of the plant material.10,11,15,16 Decomposition results a ‘dimer’ (3,6-dimethyl-2,5-diphenylpyrazine) and possibly smaller fragments. Both the dimer and phenylpropanedione have been isolated from khat extracts.15 As cathinone is presumably the main psychoactive component of khat, this explains why fresh leaves are preferred and why khat is wrapped up in banana leaves to preserve freshness.

The phenylalkylamine content of khat leaves varies within wide limits. Fresh khat from different origin contained on the average 36 mg cathinone, 120 mg cathine, and 8 mg norephedrine per 100 gram of leaves.7 Toennes et al. found 114 mg cathinone, 83 mg cathine and 44 mg norephedrine in 100 gram of khat leaves confiscated at Frankfurt airport.17 Widler et al. found 102 mg cathinone, 86 mg cathine and 47 mg norephedrine in 100 gram of fresh leaves from Kenya confiscated at Geneva Airport.18 Al-Motarreb et al. reported higher levels of cathinone in fresh leaves: 78-343 mg/100 gram.8 Khat leaves also contain considerable amounts of tannins (up to 10% in dried material) and flavonoids.8,19

Pharmacologic effects of Khat

Khat contains many different compounds and therefore khat chewing may have many different effects. The major effects include those on the gastro-intestinal system and on the nervous system. Constipation, urine retention and acute cardiovascular effects may be regarded as autonomic (peripheral) nervous system effects; increased alertness, dependence, tolerance and psychiatric symptoms as effects on the central nervous system. As cathinone, and to a lesser extent cathine, are held responsible for the effects of khat on the nervous system, the effects of the many other constituents of the khat plant are frequently overlooked. As a consequence, much research has been focused on the pharmacological effects of cathinone and cathine, and much less on the other constituents of khat. Because of the large number of different compounds in khat, it is not feasible to include all effects of all components of khat. But this report will focus on the psychoactive properties of khat and the main psychoactive compounds, cathinone and cathine, found in khat.

Animal Studies

Behavioral effects

Rats fed C. edulis material (extract or whole) show increased locomotor activity and reduced weight gain.20 Retardation of growth rate was considered to be due to decreased absorption of food and not due to decreased food consumption. In pregnant rats, khat reduces food consumption and maternal weight gain, and also lowers the food efficiency index.21

Many reports have since confirmed the enhanced locomotor activity. In addition, khat extracts and (-)-cathinone produce stereotyped behavior, self-administration and anorectic effects in animal species.15,22-26 Qualitatively, this behavior is similar to that evoked by amphetamine [S-(+)-amphetamine].27,28

Both khat extract and (-)-cathinone enhance baseline aggressive behavior of isolated rats.29 Furthermore, (-)-cathinone is capable to produce conditioned place-preference in rats at the dose of 1.6 mg/kg that results increased locomotor activity, thus showing the rewarding effect of the drug.30,31 A lower dose of cathinone (0.2 mg/kg) that did not increase locomotion, also failed to show conditioned place preference. Cathinone is also able to act as a discriminative stimulus in a food-reinforced operant task.32

(-)-Cathinone appears to have stronger effects than cathine [(+)-norpseudoephedrine] and norephedrine [(-)-norephedrine].11,27 For example, it was 7-10 times more potent than cathine on a behavioral measure of food intake.33 Compared to cathine, cathinone also has a more rapid onset of action, which agrees with its higher lipophilic character facilitating entry into the central nervous system, and a shorter duration of action, which agrees with the rapid metabolism of cathinone.11,27,33

Dopaminergic antagonists (e.g. haloperidol) and dopamine release inhibitors are able to block partially the activity-enhancing properties of (-)-cathinone.23,34 but this has not been confirmed in another study.35 Generally, cathinone is not considered a direct dopamine agonist but rather a presynaptic releaser and re-uptake inhibitor of dopamine.10 (-)-Cathinone also releases radioactivity from rat striatal tissue pre-labeled with H-serotonin, similar to (+)-amphetamine although one-third as potent.36 Apparently, (-)-cathinone shares important effects of (+)-amphetamine on neurotransmission. Further evidence for serotonergic involvement is given in a recent study in which both khat extract and cathinone produced a significant depletion of serotonin and its metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid in both the anterior and posterior striatum.29

Locomotor sensitization and deficits in prepulse inhibition (PPI) induced by psychostimulants are two paradigms that have been widely studied as animal behavioral models of amphetamine psychosis. Repeated oral administration of a standardized C. edulis extract (containing a dose of 1 mg cathinone per kg body weight) or (-)-cathinone (1.5 mg/kg) to rats induced a strong locomotor sensitization and led to a gradual deficit in prepulse inhibition.37,38 The behavioral sensitization was long-lasting and persisted after cessation of the treatments, comparable to amphetamine-induced sensitization. Clozapine, an atypical antipsychotic agent, was able to reverse this behavioral sensitization and the PPI deficits induced by C. edulis extract or cathinone.38 These results may support the reports on khat-induced psychosis in humans. Neurotransmitter level analysis showed a significant increase in the level of dopamine in the prefrontal cortex (P < 0.05). There was also a significant decrease in the level of serotonin in the nucleus accumbens (P < 0.05) and its metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid in the prefrontal cortex (P < 0.01). In the remaining regions (anterior and posterior striatum) no significant changes were found.

Cardiovascular effects

Cathinone has vasoconstrictor activity in isolated perfused hearts from guinea pigs.39 The effect was unlikely to be due to an indirect action by release of noradrenaline from sympathetic nerve endings or due to a direct action on alpha1-adrenoreceptors. (-)-Cathinone is able to potentiate noradrenaline-evoked contractions of the rat right ventricle40 and inhibit the uptake of noradrenaline into ventricular slices by a mechanism involving competitive blockade of the noradrenaline transporter.41 The vasoconstrictor activity of cathinone explains the increase in blood pressure seen in humans42 and in animals,43 and might be related to the increased incidence of myocardial infarction occurring during khat sessions, i.e. during the khat-effective period,44 and associated with heavy khat chewing.45

Effects on the adrenocortical function

In rabbits, a khat extract given orally for 30 successive days induced a decrease in adrenal cholesterol, glycogen, ascorbic acid and an increase in adrenal phosphorylase activity, serum free fatty acids and urinary 17-hydroxycorticosteroids.46 These results have been interpreted as a stimulating effect of khat on adrenocortical function. This effect was also seen after oral administration of cathinone and cathine (6.5 mg/kg).

Effects on the reproductive system

Animal data are conflicting. Treatment of male mice with a khat extract over a period of 6 weeks produced a dose-dependent reduction in fertility rate in female mice in the first week after the 6-week khat treatment.47 In cathinone-treated rats, a significant decrease in sperm count and motility, and an increase in the number of abnormal sperm cells were found.48 Histopathological examination of the testes revealed degeneration of interstitial tissue, cellular infiltration and atrophy of Sertoli and Leydig cells in cathinone-treated animals. Cathinone also produced a significant decrease in plasma testosterone levels of the rats. Although both enantiomers of cathinone produced deleterious effects on male reproductive system, (-)-cathinone was found to be more toxic.48 In contrast, rabbits fed khat for three months had an increased rate of spermatogenesis and the Leydig cells were in good condition.49 In male adult olive baboon, crude khat extract (equivalent to 250 g leaves and shoots) given orally once a week during 2 months produced an increase in plasma testosterone levels and a decrease in the plasma levels of prolactin and cortisol.50 The testosterone results are in contrast with earlier observations in humans11 and rats.48 In biopsies taken one month after the last khat administration, no histopathological changes were found in the testis, epididymis, liver, kidney and pituitary gland of the animals. This contrasts with results of cathinone on rabbit liver, which showed increasing chronic inflammation with porto-portal fibrosis in the tissue sections obtained from animals treated with both 20% and 30% C. edulis.51 The doses and administration regimens were different and this may explain the differences. Khat given to pregnant guinea pigs reduces placental blood flow52 and produces growth retardation in the offspring.53

Human Studies

The main effects of khat chewing are on the central and peripheral nervous system, and on the oro-gastro-intestinal system (Table 1).

Table 1.

Reported and suggested adverse effects of khat in human9

| System | Adverse effects |

| Cardiovascular system | tachycardia, palpitations, hypertension, arrhythmias, vasoconstriction, myocardial infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, pulmonary edema |

| Respiratory system | tachypnea, bronchitis |

| Gastro-intestinal system | dry mouth, polydipsia, dental caries, periodontal disease, chronic gastritis, constipation, hemorrhoids, paralytic ileus, weight loss, duodenal ulcer, upper gastro-intestinal malignancy |

| Hepatobiliary system | fibrosis, cirrhosis |

| Genito-urinary system | urinary retention, spermatorrhea, spermatozoa malformations, impotence, libido change |

| Obstetric effects | low birth weight, stillbirths, impaired lactation |

| Metabolic and endocrine effects | hyperthermia, perspiration, hyperglycemia |

| Ocular effects | blurred vision, mydriasis |

| Central nervous system | dizziness, impaired cognitive functioning, fine tremor, insomnia, headaches |

| Psychiatric effects | lethargy, irritability, anorexia, psychotic reactions, depressive reactions, hypnagogic hallucinations |

Subjective effects

Khat chewing induces a state of euphoria and elation with feelings of increased alertness and arousal. This is followed by a stage of vivid discussions, loquacity and an excited mood. Thinking is characterized by a flight of ideas but without the ability to concentrate. However, at the end of a khat session the user may experience depressive mood, irritability, anorexia and difficulty to sleep.8,10 Lethargy and a sleepy state follow the next morning.

In a Yemen study with adult healthy volunteers, functional mood disturbances were reported during khat sessions (Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale). The effect on anxiety and depression was temporary and disappeared the next day.54 Many Yemenite users, however, believe that khat chewing improves their sexual desire and excitement.8 Khat chewing induced anorexia and insomnia (delayed bedtime) resulting in late wake-up next morning and low work performance in the next day.19 In the study of Toennes et al.17 subjects reported subjective feelings of alertness and being ‘energetic’. They did not report any severe adverse reactions. The chewing dose was 0.6 gram of khat leaves per kg of body weight resulting in a mean absorption dose of 45 mg of cathinone. This is about one-half to one-fourth of the regular khat dose chewed in sessions.

Effects on the urinary bladder

Khat induces a fall in average and maximum urine flow rate in healthy men19,55 The urinary effects are probably mediated through stimulation of alpha1-adrenergic receptors by cathinone. This is indicated by the complete blockage of this effect by indoramin, a selective antagonist of alpha1-adrenergic receptors.55

Effects on the gall bladder

Khat chewing has no clinically significant effect on gall bladder motility.56

Cardiovascular effects

Khat chewing induces small and transient rises in blood pressure and heart rate.8,57-61 Cathinone (0.5 mg base/kg of body weight) has similar effects coinciding with the presence of cathinone in blood plasma.42,62 These effects could be blocked by the beta1-adrenoreceptor blocker atenolol, but not by the alpha1-adrenorecptor blocker indoramin, indicating mediation through stimulation of beta1-adrenoreceptors.59

In a pharmacokinetic study, diastolic and systolic blood pressures were elevated for about 3 hours after chewing.17 The rise of blood pressure already started before the rise of alkaloid plasma concentrations, indicating an initial study engagement effect. The dose used was about one quarter (0.6 g/kg) of a traditional khat session dose and chewing was for 1 hour. This resulted in a mean oral dose of 45 mg cathinone. This rather low dose did not affect heart rate, pupil size and reaction to light, and it did not induce rotary nystagmus or impairment of reaction. All participants reported the personal feeling of being alert and ‘energetic’. An impairment of other psychophysical functions could not be objectified.17 In another study, diastolic and systolic blood pressure, mean arterial blood pressure, and heart rate were raised during the 3 hours of khat chewing and during the following hour.61

Effects on the adrenocortical function

Nencini et al. found that khat and cathinone increase adrenocorticotrophic hormone levels in humans.63

Toxicologic aspect of khat

Khat usage affects cardiovascular, digestive, respiratory, endocrine, and genito-urinary systems. In addition, it affects the nervous system and can induce paranoid psychosis and hypomanic illness with grandiose delusions.64 The effects on the nervous system resemble those of amphetamine with differences being quantitative rather than qualitative.9,19,65-68

The main toxic effects include increased blood pressure, tachycardia, insomnia, anorexia, constipation, general malaise, irritability, migraine and impaired sexual potency in men.10 Mild depressive reactions have been reported during khat withdrawal or at the end of a khat session.11,54,69 Frequent use of high doses may evoke psychotic reactions.

Biochemically, khat leaves decreased plasma cholesterol, glucose and triglycerides in rabbits,70 and increased plasma alkaline phosphatase and alanine aminotransferase in white rabbits.49 Histopathological signs of congestion of the central liver veins were observed with acute hepatocellular damage and regeneration. In addition, some kidney lesions were seen with the presence of fat droplets in the upper cortical tubules, acute cellular swelling, hyaline tubules, and acute tubular necrosis. Spleen was not affected and the histoarchitecture of the testes and cauda epididymis was normal showing, however, increased rate of spermatogenesis. The amount of khat consumed by the rabbits cannot be evaluated from the details given. The authors reported that, in general, the activity and the behavior of the animals were observed to be normal.49 Adverse effects of khat may be summarized according to the system involved.9

Khat-induced psychosis

Khat chewing can induce two kinds of psychotic reactions. First, a manic illness with grandiose delusions and second, a paranoid or schizophreniform psychosis with persecutory delusions associated with mainly auditory hallucinations, fear and anxiety, resembling amphetamine psychosis.69,71-76 Both reactions are exceptional and associated with chewing large amounts of khat.77,78 Symptoms rapidly abate when khat is withdrawn.72,79,80 In fact, khat withdrawal consistently appears to be an effective treatment of khat psychosis and anti-psychotics are usually not needed for full remission.69,78,79 Nevertheless, in most cases described in the literature antipsychotic medication has been used to alleviate the symptoms. Khat psychosis, however, is an infrequent phenomenon, probably due to the physical limits of the amount of khat leaves that can be chewed.65,66,81 Khat psychosis may be accompanied by depressive symptoms and sometimes by violent reactions.82 It has been argued that khat chewing might exacerbate symptoms in patients with pre-existing psychiatric disorder.54 Dhadphale and Omolo77 studied psychiatric morbidity among khat users. In moderate users there was no excess morbidity. Chewing more than two bundles per day was associated with increased psychiatric morbidity. Case reports confirm that adverse effects occur at high doses of khat.76,83,84

Hypnagogic hallucinations

Hypnagogic hallucinations have been reported in chronic khat users.85,86 These consist of continuous visual and/or auditory dreamlike experiences that accompany daily life and are not related to khat sessions. Patients may consider them as normal and do not usually report these hallucinations unless specifically asked about.

Impairment of cognitive functions

Adverse effects of khat chewing include impairment of perceptual-visual memory and decision-speed cognitive functions.87 This study was carried out in flight attendants during a standard aviation medical examination. Toennes and Kauert investigated plasma khat alkaloid concentrations in 19 cases suspected of driving under the influence of drugs. In all cases, cathinone or cathine was found in blood and urine, but an association between alkaloid concentrations and impaired driving could not be established. Nevertheless, the authors concluded that chronic khat use might lead to a marked deterioration of psychophysical functions.88

Neurological complications

One case history of severe leukoencephalopathy associated with khat misuse has been reported.89 electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings indicated progressive leukoencephalopathy but the relation with khat use was not proven (coinciding).

Cardiovascular complications

An increased incidence of acute myocardial infarction presenting between 2 pm and midnight, i.e. occurring during khat sessions, has been found.44 Recently, it has been reported that khat chewing is associated with acute myocardial infarction.45,90,91 The authors concluded that khat chewing is an independent dose-related risk factor for the development of acute myocardial infarction with heavy chewers having a 39-fold increased risk.45 Khat chewing has also been reported to be a significant risk factor for acute cerebral infarction.92,93 The prevalence of high blood pressure was significantly higher in the patient group than in the control group and this higher prevalence was associated with khat chewing. Another cardiovascular complication of khat chewing is the higher incidence of hemorrhoids and hemorrhoidectomy found in chronic khat chewers (62% and 45%) as compared to non-khat users (4% and 0.5%).94

Oral and gastro-intestinal complications

As a consequence of its mode of consumption, khat affects the oral cavity and the digestive tract.66 A high frequency of periodontal disease has been suggested as well as gastritis95,96 and chronic recurrent subluxation and dislocation of the temporomandibular joint.97 Epidemiological studies, however, have yielded conflicting results. Several studies indicated no such detrimental effects of khat chewing and suggested beneficial effects on the periodontium.98,99 Another study could not show a significant role of khat chewing and suggested bad oral hygiene as a major factor in periodontal disease.100 No significant association could be found between khat chewing and oral leukoplakia in a Kenyan study.101 In a recent study, the authors concluded that khat chewing does not seem to increase the colonization of gingival plaque and instead, khat chewing might induce a microbial profile compatible with gingival health.102 Recently, oral keratotic lesions at the site of chewing103 and plasma cell gingivitis (allergic reaction to khat)104 have been reported. The tannins present in khat leaves are held responsible for the gastritis that has been observed.65,72

Cancer

In a survey that reviewed cancers for the past two years in the Asir region of Saudi Arabia, 28 patients with head and neck cancer were found.105,106 Ten of these presented with a history of khat chewing. All were non-smoking chewers and all of them had used khat over a period of 25 years or longer. Eight of these ten presented with oral cancers. In some cases the malignant lesion occurred at exactly the same site where the khat bolus was held. The authors concluded that a strong correlation between khat chewing and oral cancer existed. In another study performed in Yemen, 30 of 36 patients suffering from squamous cell carcinoma (17 cases in the oral cavity, one in oropharynx, 15 in nasopharynx and 3 cases in larynx) were habitual khat chewers from childhood.107 The authors considered khat as an important contributing factor. It was reported that 50% of khat chewers develop oral mucosal keratosis.98 Keratosis of the oral buccal mucosa is considered as a pre-cancerous lesion that may develop into oral cancer.108 Recently, Ali et al. reported that 22.4% of khat chewers had oral keratotic white lesions at the site of khat chewing, while only 0.6% of non-chewers had white lesions in the oral cavity.103 The prevalence of these lesions and their severity increased with frequency and duration of khat use. In human leukaemia cell lines and in human peripheral blood leucocytes, khat extract, cathinone and cathine produced a rapid and synchronized cell death with all the morphological and biochemical features of apoptotic cell death.109

Reproductive system

Detailed studies on the effects of khat on human reproduction are lacking. However, the available data suggest that chronic use may cause spermatorrhea and may lead to decreased sexual functioning and impotence.65,110 In chronic chewers, sperm count, volume and motility were decreased.111,112 Deformed spermatozoa (65% of total) have been found in Yemenite daily khat users, with different patterns including head and flagella malformations in complete spermatozoa, aflagellate heads, headless flagella, and multiple heads and flagella.111 In pregnant women, khat consumption may have detrimental effects on uteri-placental blood flow and as a consequence, on fetal growth and development.110 Lower mean birth weights have been reported in khat-chewing mothers compared to non-using mothers indicating an association between khat chewing and decreased birth weight.113

Genotoxicity and teratogenic effects

Orally administered khat extract induced dominant lethal mutations in mice,47 chromosomal aberrations in sperm cells in mice,114 and teratogenic effects in rats.21 With the micronucleus test to determine genetic damage, an 8-fold increase in micronucleated buccal mucosa cells was seen among khat chewing individuals living in the area of the horn of Africa.115 Khat consumption did not lead to a detectable elevation of micronucleated bladder mucosa cells. Among heavy khat chewers, 81% of the micronuclei had a centromere signal indicating that khat is aneuploidogenic. The effect of khat, tobacco and alcohol was found to be additive. These results suggest that khat consumption, especially when accompanied by alcohol and tobacco, might be a potential cause of oral malignancy.115

Conclusion

Several studies across the globe have reported khat-chewing as a harmful activity on health. Many different compounds are found in khat including alkaloids, terpenoids, flavonoids, sterols, glycosides, tannins, amino acids, vitamins and minerals the major pharmacologic and toxic effect come from the phenylalkylamines and the cathedulins. The major effects of khat include those on the gastro-intestinal system and central nervous system but also affect on cardiovascular, respiratory, endocrine, and genito-urinary systems. The effects on the central nervous system resemble those of amphetamine with differences being quantitative. The main toxic effects include increased blood pressure, tachycardia, insomnia, anorexia, constipation, general malaise, irritability, migraine and impaired sexual potency in men. Since this is a major social issue particularly in the East Africa, raising awareness with the general public in terms of the harmful effects of khat-chewing. This can be accomplished via appropriate communication strategies by using printed materials and electronic media.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ageely HM. Prevalence of Khat chewing in college and secondary (high) school students of Jazan region, Saudi Arabia. Harm Reduct J. 2009;6:11. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luqman W, Danowski TS. The use of khat (Catha edulis) in Yemen. Social and medical observations. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85(2):246–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-85-2-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nencini P, Ahmed AM, Amiconi G, Elmi AS. Tolerance develops to sympathetic effects of khat in humans. Pharmacology. 1984;28(3):150–4. doi: 10.1159/000137956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalix P. Khat: a plant with amphetamine effects. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1988;5(3):163–9. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(88)90005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kennedy JG, Teague J, Rokaw W, Cooney E. A medical evaluation of the use of qat in North Yemen. Soc Sci Med. 1983;17(12):783–93. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halbach H. Medical aspects of the chewing of khat leaves. Bull World Health Organ. 1972;47(1):21–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geisshusler S, Brenneisen R. The content of psychoactive phenylpropyl and phenylpentenyl khatamines in Catha edulis Forsk. of different origin. J Ethnopharmacol. 1987;19(3):269–77. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(87)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Motarreb A, Baker K, Broadley KJ. Khat: pharmacological and medical aspects and its social use in Yemen. Phytother Res. 2002;16(5):403–13. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox G, Rampes H. Adverse effects of khat: a review. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2003;9:456–63. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nencini P, Ahmed AM. Khat consumption: a pharmacological review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1989;23(1):19–29. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(89)90029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalix P, Braenden O. Pharmacological aspects of the chewing of khat leaves. Pharmacol Rev. 1985;37(2):149–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kite GC, Ismail M, Simmonds MS, Houghton PJ. Use of doubly protonated molecules in the analysis of cathedulins in crude extracts of khat (Catha edulis) by liquid chromatography/serial mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2003;17(14):1553–64. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalix P, Geisshusler S, Brenneisen R. The effect of phenylpentenyl-khatamines on the release of radioactivity from rat striatal tissue prelabelled with [3H]dopamine. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1987;39(2):135–7. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1987.tb06961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalix P, Geisshusler S, Brenneisen R. Differential effect of phenylpropyl- and phenylpentenyl-khatamines on the release of radioactivity from rabbit atria prelabelled with 3H-noradrenaline. Pharm Acta Helv. 1987;62(12):332–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Review of the pharmacology of khat Review of the pharmacology of khat. Bull Narc. 1980;32:83–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brenneisen R, Geisshusler S. Psychotropic drugs. III. Analytical and chemical aspects of Catha edulis Forsk. Pharm Acta Helv. 1985;60(11):290–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toennes SW, Harder S, Schramm M, Niess C, Kauert GF. Pharmacokinetics of cathinone, cathine and norephedrine after the chewing of khat leaves. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;56(1):125–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01834.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Widler P, Mathys K, Brenneisen R, Kalix P, Fisch HU. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of khat: a controlled study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;55(5):556–62. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1994.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hassan NA, Gunaid AA, EI Khally FM, Murray-Lyon IM. The subjective effects of chewing Qat leaves in human volunteers. Ann Saudi Med. 2002;22(1-2):34–7. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2002.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maitai CK. The toxicity of the plant Catha edulis in rats. Toxicon. 1977;15(4):363–6. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(77)90020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Islam MW, al-Shabanah OA, al-Harbi MM, al-Gharably NM. Evaluation of teratogenic potential of khat (Catha edulis Forsk.) in rats. Drug Chem Toxicol. 1994;17(1):51–68. doi: 10.3109/01480549409064046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yanagita T. Studies on cathinones: cardiovascular and behavioral effects in rats and self-administration experiment in rhesus monkeys. NIDA Res Monogr. 1979;27:326–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schechter MD. Dopaminergic mediation of a behavioral effect of l-cathinone. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1986;25(2):337–40. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon TL, Meehan SM, Schechter MD. Differential effects of nicotine but not cathinone on motor activity of P and NP rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1993;44(3):657–9. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90182-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calcagnetti DJ, Schechter MD. Increases in the locomotor activity of rats after intracerebral administration of cathinone. Brain Res Bull. 1992;29(6):843–6. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(92)90153-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalix P. Hypermotility of the amphetamine type induced by a constituent of khat leaves. Br J Pharmacol. 1980;68(1):11–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1980.tb10690.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zelger JL, Schorno HX, Carlini EA. Behavioural effects of cathinone, an amine obtained from Catha edulis Forsk: comparisons with amphetamine, norpseudoephedrine, apomorphine and nomifensine. Bull Narc. 1980;32(3):67–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goudie AJ. Comparative effects of cathinone and amphetamine on fixed-interval operant responding: a rate-dependency analysis. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1985;23(3):355–65. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Banjaw MY, Miczek K, Schmidt WJ. Repeated Catha edulis oral administration enhances the baseline aggressive behavior in isolated rats. J Neural Transm. 2006;113(5):543–56. doi: 10.1007/s00702-005-0356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calcagnetti DJ, Schechter MD. Reducing the time needed to conduct conditioned place preference testing. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1992;16(6):969–76. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(92)90114-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schechter MD, Meehan SM. Conditioned place preference produced by the psychostimulant cathinone. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;232(1):135–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90739-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schechter MD, Glennon RA. Cathinone, cocaine and methamphetamine: similarity of behavioral effects. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1985;22(6):913–6. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90295-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterson DW, Maitai CK, Sparber SB. Relative potencies of two phenylalkylamines found in the abused plant Catha edulis, khat. Life Sci. 1980;27(22):2143–7. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(80)90496-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Calcagnetti DJ, Schechter MD. Psychostimulant-induced activity is attenuated by two putative dopamine release inhibitors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1992;43(4):1023–31. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(92)90476-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang D, Wilson MC. Comparative discriminative stimulus properties of dl-cathinone, d-amphetamine, and cocaine in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1986;24(2):205–10. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90339-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalix P. Effect of the alkaloid (-)-cathinone on the release of radioactivity from rat striatal tissue prelabelled with 3H-serotonin. Neuropsychobiology. 1984;12(2-3):127–9. doi: 10.1159/000118124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Banjaw MY, Schmidt WJ. Behavioural sensitisation following repeated intermittent oral administration of Catha edulis in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2005;156(2):181–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Banjaw MY, Fendt M, Schmidt WJ. Clozapine attenuates the locomotor sensitisation and the prepulse inhibition deficit induced by a repeated oral administration of Catha edulis extract and cathinone in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2005;160(2):365–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Motarreb AL, Broadley KJ. Coronary and aortic vasoconstriction by cathinone, the active constituent of khat. Auton Autacoid Pharmacol. 2003;23(5-6):319–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-8673.2004.00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cleary L, Buber R, Docherty JR. Effects of amphetamine derivatives and cathinone on noradrenaline-evoked contractions of rat right ventricle. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;451(3):303–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cleary L, Docherty JR. Actions of amphetamine derivatives and cathinone at the noradrenaline transporter. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;476(1-2):31–4. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)02173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brenneisen R, Fisch HU, Koelbing U, Geisshusler S, Kalix P. Amphetamine-like effects in humans of the khat alkaloid cathinone. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;30(6):825–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1990.tb05447.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kohli JD, Goldberg LI. Cardiovascular effects of (--)-cathinone in the anaesthetized dog: comparison with (+)-amphetamine. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1982;34(5):338–40. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1982.tb04722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Motarreb A, Al-Kebsi M, Al-Adhi B, Broadley KJ. Khat chewing and acute myocardial infarction. Heart. 2002;87(3):279–80. doi: 10.1136/heart.87.3.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Motarreb A, Briancon S, Al-Jaber N, Al-Adhi B, Al-Jailani F, Salek MS, et al. Khat chewing is a risk factor for acute myocardial infarction: a case-control study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;59(5):574–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02358.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahmed MB, el-Qirbi AB. Biochemical effects of Catha edulis, cathine and cathinone on adrenocortical functions. J Ethnopharmacol. 1993;39(3):213–6. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(93)90039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tariq M, Qureshi S, Ageel AM, al-Meshal IA. The induction of dominant lethal mutations upon chronic administration of khat (Catha edulis) in albino mice. Toxicol Lett. 1990;50(2-3):349–53. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(90)90028-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Islam MW, Tariq M, Ageel AM, el-Feraly FS, al-Meshal IA, Ashraf I. An evaluation of the male reproductive toxicity of cathinone. Toxicology. 1990;60(3):223–34. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(90)90145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-Mamary M, Al-Habori M, Al-Aghbari AM, Baker MM. Investigation into the toxicological effects of Catha edulis leaves: a short term study in animals. Phytother Res. 2002;16(2):127–32. doi: 10.1002/ptr.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mwenda JM, Owuor RA, Kyama CM, Wango EO, M'Arimi M, Langat DK. Khat (Catha edulis) up-regulates testosterone and decreases prolactin and cortisol levels in the baboon. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;103(3):379–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Al-Habori M, Al-Aghbari A, Al-Mamary M, Baker M. Toxicological evaluation of Catha edulis leaves: a long term feeding experiment in animals. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;83(3):209–17. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jansson T, Kristiansson B, Qirbi A. Effect of khat on uteroplacental blood flow in awake, chronically catheterized, late-pregnant guinea pigs. J Ethnopharmacol. 1988;23(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(88)90111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jansson T, Kristiansson B, Qirbi A. Effect of khat on maternal food intake, maternal weight gain and fetal growth in the late-pregnant guinea pig. J Ethnopharmacol. 1988;23(1):11–7. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(88)90110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hassan NA, Gunaid AA, El-Khally FM, Murray-Lyon IM. The effect of chewing Khat leaves on human mood. Saudi Med J. 2002;23(7):850–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nasher AA, Qirbi AA, Ghafoor MA, Catterall A, Thompson A, Ramsay JW, et al. Khat chewing and bladder neck dysfunction. A randomized controlled trial of alpha 1-adrenergic blockade. Br J Urol. 1995;75(5):597–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1995.tb07415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murugan N, Burkhill G, Williams SG, Padley SP, Murray-Lyon IM. The effect of khat chewing on gallbladder motility in a group of volunteers. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;86(2-3):225–7. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(03)00079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kalix P, Brenneisen R, Koelbing U, Fisch HU, Mathys K. Khat, a herbal drug with amphetamine properties. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1991;121(43):1561–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kalix P. Cathinone, a natural amphetamine. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1992;70(2):77–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1992.tb00434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hassan NA, Gunaid AA, El-Khally FM, Al-Noami MY, Murray-Lyon IM. Khat chewing and arterial blood pressure. A randomized controlled clinical trial of alpha-1 and selective beta-1 adrenoceptor blockade. Saudi Med J. 2005;26(4):537–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nencini P, Ahmed AM, Elmi AS. Subjective effects of khat chewing in humans. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1986;18(1):97–105. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(86)90118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hassan NA, Gunaid AA, Abdo-Rabbo AA, Abdel-Kader ZY, al-Mansoob MA, Awad AY, et al. The effect of Qat chewing on blood pressure and heart rate in healthy volunteers. Trop Doct. 2000;30(2):107–8. doi: 10.1177/004947550003000219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kalix P, Geisshusler S, Brenneisen R, Koelbing U, Fisch HU. Cathinone, a phenylpropylamine alkaolid from khat leaves that has amphetamine effects in humans. NIDA Res Monogr. 1990;105:289–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nencini P, Ahmed AM, Amiconi G, Elmi AS. Tolerance develops to sympathetic effects of khat in humans. Pharmacology. 1984;28(3):150–4. doi: 10.1159/000137956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kalix P. Khat: a plant with amphetamine effects. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1988;5(3):163–9. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(88)90005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Halbach H. Medical aspects of the chewing of khat leaves. Bull World Health Organ. 1972;47(1):21–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kalix P. Pharmacological properties of the stimulant khat. Pharmacol Ther. 1990;48(3):397–416. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(90)90057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tariq M, Al-Meshal I, Al-Saleh A. Toxicity studies on Catha edulis. Dev Toxicol Environ Sci. 1983;11:337–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dhaifalah I, Santavy J. Khat habit and its health effect. A natural amphetamine. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2004;148(1):11–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pantelis C, Hindler CG, Taylor JC. Khat, toxic reactions to this substance, its similarities to amphetamine, and the implications of treatment for such patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1989;6(3):205–6. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(89)90008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Al-Habori M, Al-Mamary M. Long-term feeding effects of Catha edulis leaves on blood constituents in animals. Phytomedicine. 2004;11(7-8):639–44. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2003.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dhadphale M, Mengech A, Chege SW. Miraa (catha edulis) as a cause of psychosis. East Afr Med J. 1981;58(2):130–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pantelis C, Hindler CG, Taylor JC. Use and abuse of khat (Catha edulis): a review of the distribution, pharmacology, side effects and a description of psychosis attributed to khat chewing. Psychol Med. 1989;19(3):657–68. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700024259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gough SP, Cookson IB. Khat-induced schizophreniform psychosis in UK. Lancet. 1984;1(8374):455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McLaren P. Khat psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:712–3. doi: 10.1192/s0007125000123438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yousef G, Huq Z, Lambert T. Khat chewing as a cause of psychosis. Br J Hosp Med. 1995;54(7):322–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Critchlow S, Seifert R. Khat-induced paranoid psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:219–22. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dhadphale M, Omolo OE. Psychiatric morbidity among khat chewers. East Afr Med J. 1988;65(6):355–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jager AD, Sireling L. Natural history of Khat psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1994;28(2):331–2. doi: 10.3109/00048679409075648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nielen RJ, van der Heijden FM, Tuinier S, Verhoeven WM. Khat and mushrooms associated with psychosis. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2004;5(1):49–53. doi: 10.1080/15622970410029908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Giannini AJ, Castellani S. A manic-like psychosis due to khat (Catha edulis Forsk.). J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1982;19(5):455–9. doi: 10.3109/15563658208992500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kalix P. Khat: scientific knowledge and policy issues. Br J Addict. 1987;82(1):47–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Odenwald M, Neuner F, Schauer M, Elbert T, Catani C, Lingenfelder B, et al. Khat use as risk factor for psychotic disorders: a cross-sectional and case-control study in Somalia. BMC Med. 2005;3:5. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Alem A, Shibre T. Khat induced psychosis and its medico-legal implication: a case report. Ethiop Med J. 1997;35(2):137–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stefan J, Mathew B. Khat chewing: an emerging drug concern in Australia? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39(9):842–3. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01688_4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Numan N. Exploration of adverse psychological symptoms in Yemeni khat users by the Symptoms Checklist-90 (SCL-90). Addiction. 2004;99(1):61–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Granek M, Shalev A, Weingarten AM. Khat-induced hypnagogic hallucinations. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1988;78(4):458–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1988.tb06367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Khattab NY, Amer G. Undetected neuropsychophysiological sequelae of khat chewing in standard aviation medical examination. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1995;66(8):739–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Toennes SW, Kauert GF. Driving under the influence of khat--alkaloid concentrations and observations in forensic cases. Forensic Sci Int. 2004;140(1):85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2003.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Morrish PK, Nicolaou N, Brakkenberg P, Smith PE. Leukoencephalopathy associated with khat misuse. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67(4):556. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.4.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Alkadi HO, Noman MA, Al-Thobhani AK, Al-Mekhlafi FS, Raja'a YA. Clinical and experimental evaluation of the effect of Khat-induced myocardial infarction. Saudi Med J. 2002;23(10):1195–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kuczkowski KM. Re: cathinone: a new differential in the diagnosis of pregnancy induced hypertension. East Afr Med J. 2004;81(8):436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kuczkowski KM. Herbal ecstasy: cardiovascular complications of khat chewing in pregnancy. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 2005;56(1):19–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mujlli HM, Bo X, Zhang L. The effect of Khat (Catha edulis) on acute cerebral infarction. Neurosciences. 2005;10:219–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Al-Hadrani AM. Khat induced hemorrhoidal disease in Yemen. Saudi Med J. 2000;21(5):475–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kalix P. Hyperthermic response to (-)-cathinone, an alkaloid of Catha edulis (khat). J Pharm Pharmacol. 1980;32(9):662–3. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1980.tb13031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kennedy JG, Teague J, Rokaw W, Cooney E. A medical evaluation of the use of qat in North Yemen. Soc Sci Med. 1983;17(12):783–93. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kummoona R. Surgical reconstruction of the temporomandibular joint for chronic subluxation and dislocation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;30(4):344–8. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2000.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hill CM, Gibson A. The oral and dental effects of q'at chewing. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;63(4):433–6. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(87)90255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jorgensen E, Kaimenyi JT. The status of periodontal health and oral hygiene of Miraa (catha edulis) chewers. East Afr Med J. 1990;67(8):585–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mengel R, Eigenbrodt M, Schunemann T, Flores-de-Jacoby L. Periodontal status of a subject sample of Yemen. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23(5):437–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Macigo FG, Mwaniki DL, Guthua SW. The association between oral leukoplakia and use of tobacco, alcohol and khat based on relative risks assessment in Kenya. Eur J Oral Sci. 1995;103(5):268–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1995.tb00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Al-Hebshi NN, Skaug N. Effect of khat chewing on 14 selected periodontal bacteria in sub- and supragingival plaque of a young male population. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2005;20(3):141–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2004.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ali AA, Al-Sharabi AK, Aguirre JM, Nahas R. A study of 342 oral keratotic white lesions induced by qat chewing among 2500 Yemeni. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004;33(6):368–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2004.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Marker P, Krogdahl A. Plasma cell gingivitis apparently related to the use of khat: report of a case. Br Dent J. 2002;192(6):311–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Makki L. Oral carcinomas and their relationship to khat and shamma abuses. Heidelberg, Germany: University of Heidelberg; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Soufi HE, Kameswaran M, Malatani T. Khat and oral cancer. J Laryngol Otol. 1991;105(8):643–5. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100116913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nasr AH, Khatri ML. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in Hajjah, Yemen. Saudi Med J. 2000;21(6):565–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Goldenberg D, Lee J, Koch WM, Kim MM, Trink B, Sidransky D, et al. Habitual risk factors for head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131(6):986–93. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dimba EA, Gjertsen BT, Bredholt T, Fossan KO, Costea DE, Francis GW, et al. Khat (Catha edulis)-induced apoptosis is inhibited by antagonists of caspase-1 and -8 in human leukaemia cells. Br J Cancer. 2004;91(9):1726–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mwenda JM, Arimi MM, Kyama MC, Langat DK. Effects of khat (Catha edulis) consumption on reproductive functions: a review. East Afr Med J. 2003;80(6):318–23. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v80i6.8709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.El-Shoura SM, Abdel Aziz M, Ali ME, El-Said MM, Ali KZM, Kemeir MA, et al. Andrology: Deleterious effects of khat addiction on semen parameters and sperm ultrastructure. Human Reproduction. 1995;10(9):2295–300. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hakim LY. Influence of khat on seminal fluid among presumed infertile couples. East Afr Med J. 2002;79(1):22–8. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v79i1.8920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Abdul GN, Eriksson M, Kristiansson B, Qirbi A. The influence of khat-chewing on birth-weight in full-term infants. Soc Sci Med. 1987;24(7):625–7. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Qureshi S, Tariq M, Parmar NS, al-Meshal IA. Cytological effects of khat (Catha edulis) in somatic and male germ cells of mice. Drug Chem Toxicol. 1988;11(2):151–65. doi: 10.3109/01480548808998219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kassie F, Darroudi F, Kundi M, Schulte-Hermann R, Knasmuller S. Khat (Catha edulis) consumption causes genotoxic effects in humans. Int J Cancer. 2001;92(3):329–32. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]