Abstract

Objective

To assess for the presence of gastric dysmotility in familial and sporadic Parkinson disease (PD).

Methods

10 subjects with familial Parkinson disease (fPD), 35 subjects with sporadic Parkinson disease (sPD), and 15 controls, all from academic tertiary care movement disorders centers, were studied. fPD was defined as the presence of at least 2 affected individuals within 2–3 consecutive generations in a family. Molecular genetic analysis has not revealed, thus far, any known genomic abnormality in these families. Gastric emptying was assessed by dynamic abdominal scintigraphy over 92 min following ingestion of a solid meal containing 99mTc-labeled colloid of 40 MBq activity. The main outcome measures were gastric emptying half-time and radiotracer activity over the gastric area at 46 and at 92 min.

Results

Gastric emptying time was delayed in 60% of subjects with PD. In comparison to mean t1/2 of 38 ± 7 min in controls, mean t1/2 was 58 ± 25 min in fPD (p = 0.02) and 46 ± 25 min in sPD (p = 0.10). Both fPD and sPD groups included subjects with delayed gastric emptying at an early stage of disease.

Conclusions

Patients with fPD showed significantly delayed gastric emptying in comparison to normal age-matched individuals. Further studies of gastrointestinal dysfunction in PD, particularly fPD, are warranted.

Keywords: Gastric emptying, Familial, Parkinson disease, Radionuclide imaging

1. Introduction

Gastrointestinal dysfunction is an important nonmotor manifestation of Parkinson disease (PD) [1–4]. Pooling saliva, pharyngeal or esophageal dysphagia, delayed gastric emptying, constipation and difficulty defecating are common in PD [5–7]. The commonest gastrointestinal disturbance is constipation, which may precede motor signs [8–10].

Several studies have reported reduced gastric motility in PD, up to 100% of individuals with PD may show some gastric emptying abnormality during the course of the disease [7,11–14]. The clinical presentation of delayed gastric emptying is complex and includes erratic absorption of antiparkinsonian drugs with its pharmacokinetic implications.

It is not clear whether impaired gastric emptying only develops in PD patients with advanced disease. Some studies have suggested that gastroparesis increases with PD progression [11,13,14], but others have failed to demonstrate any relationship between gastroparesis and PD duration or severity [12].

It has been shown that familial (fPD) due to mutations in the α-synuclein (SNCA) and Parkin (PRKN) genes have different patterns of autonomic involvement [15–17]. To our knowledge, no previous studies have specifically examined, whether or to what degree gastric emptying is impaired in patients with fPD.

Therefore, we investigated gastric emptying in patients with fPD and sporadic PD (sPD) of varying disease duration using abdominal scintigraphy and compared the results to those from a control group.

2. Methods

The study group comprised 45 subjects, which included 10 subjects with fPD (3 females and 7 males) aged 59.0 ± 8.2 years (range: 49–77 years) and 35 subjects with sPD (13 females and 22 males) aged 60.5 ± 9.9 years (range: 38–78 years). Separation of cases into fPD and sPD group was done retrospectively. The control group included 15 healthy volunteers (6 females and 9 males) aged 59.5 ± 9.7 years (range: 48–76 years) matched by age, sex and body weight. The study population was Caucasian and of Polish extraction. All individuals gave written informed consent, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Collegium Medicum Jagiellonian University.

The diagnosis of PD was established according to the UK Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank criteria (family history was not used as an exclusion criterion). Severity of parkinsonism was assessed using the Hoehn&Yahr scale (H&Y) and Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS). Cognitive dysfunction was evaluated by the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE). fPD was defined as the presence of at least two affected individuals within 2–3 consecutive generations in a family. In 7 out of 9 families there were 3 or more affected individuals, including 1 family with 10 and 1 family with 7 affected individuals. Families presented with a dominant pattern of disease inheritance, however known genetic causes of PD were excluded. The phenotype of fPD was consistent with typical levodopa-responsive parkinsonism.

Age at onset of symptoms was 37–70 years in fPD and 30–70 years in sPD. Duration of PD was 4–18 years in fPD (mean 8.4 ± 5.2 years) and 2–17 years in sPD (mean 7.1 ±4.3 years). Duration of PD was defined as the time from the onset of first motor symptom to the time of entry into the study. The clinical features of both groups are presented in Tables 1a and 1b.

Table 1.

| a | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical data and results of scintigraphy examination in individuals with familial Parkinson disease. | |||||||||

| Sex | Age (years) |

H&Y (stage) |

Disease duration (years) |

Age at onset (years) |

Response to l-dopa |

S46min[%] (%) |

S92min[%] (%) |

St1/2 (min) |

|

| 1 | M | 62 | I | 4 | 58 | + | 85 | 60 | 92 |

| 2 | M | 49 | I | 6 | 43 | + | 30 | 6 | 30 |

| 3 | M | 51 | II | 14 | 37 | + | 86 | 8 | 61 |

| 4 | F | 54 | II | 6 | 48 | + | 70 | 3 | 57 |

| 5 | M | 66 | II | 18 | 48 | + | 92 | 31 | 77 |

| 6 | F | 56 | II | 9 | 47 | + | 68 | 27 | 58 |

| 7 | M | 77 | II | 7 | 70 | + | 98 | 89 | 92 |

| 8 | M | 55 | II/III | 4 | 51 | + | 79 | 0 | 59 |

| 9 | M | 58 | II | 14 | 44 | + | 10 | 5 | 35 |

| 10 | F | 62 | I | 2 | 60 | + | 25 | 0 | 23 |

| Mean | N/A | 59.0 | N/A | 8.4 | 50.6 | N/A | 64 | 23 | 58 |

| SD | N/A | 8.2 | N/A | 5.2 | 9.6 | N/A | 32 | 30 | 25 |

| b | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical data and results of scintigraphy examination in individuals with sporadic Parkinson disease. | |||||||||

| Sex | Age (years) |

H&Y (stage) |

Disease duration (years) |

Age at onset (years) |

Response to l-dopa |

S46min[%] (%) |

S92min[%] (%) |

St1/2 (min) |

|

| 1 | F | 61 | II | 4 | 57 | + | 69 | 0 | 57 |

| 2 | M | 49 | II | 12 | 37 | + | 67 | 0 | 63 |

| 3 | F | 49 | II | 3 | 46 | + | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| 4 | M | 48 | II | 4 | 44 | + | 39 | 0 | 65 |

| 5 | F | 68 | II | 8 | 60 | + | 30 | 0 | 31 |

| 6 | F | 66 | III | 5 | 61 | + | 39 | 0 | 36 |

| 7 | F | 71 | II | 10 | 61 | + | 20 | 0 | 8 |

| 8 | F | 58 | III | 6 | 52 | + | 67 | 0 | 59 |

| 9 | M | 63 | III | 12 | 51 | + | 62 | 50 | 68 |

| 10 | M | 56 | III | 11 | 45 | + | 83 | 81 | 92 |

| 11 | M | 77 | III | 12 | 65 | + | 84 | 58 | 92 |

| 12 | M | 58 | IV | 10 | 48 | + | 40 | 20 | 30 |

| 13 | M | 58 | II | 7 | 51 | + | 37 | 0 | 23 |

| 14 | M | 54 | II | 2 | 52 | + | 36 | 14 | 17 |

| 15 | F | 38 | II | 3 | 35 | + | 50 | 5 | 48 |

| 16 | M | 58 | II | 4 | 54 | + | 35 | 33 | 10 |

| 17 | M | 64 | II | 2 | 62 | + | 53 | 49 | 45 |

| 18 | M | 46 | II | 2 | 44 | + | 83 | 40 | 68 |

| 19 | F | 56 | II | 7 | 48 | + | 75 | 28 | 64 |

| 20 | F | 59 | II | 2 | 57 | + | 35 | 17 | 24 |

| 21 | F | 70 | II | 2 | 68 | + | 48 | 19 | 43 |

| 22 | F | 70 | III | 7 | 63 | + | 86 | 41 | 83 |

| 23 | M | 58 | III | 5 | 53 | + | 72 | 13 | 76 |

| 24 | F | 73 | II | 4 | 69 | + | 56 | 48 | 64 |

| 25 | M | 75 | III | 13 | 62 | + | 58 | 27 | 41 |

| 26 | F | 63 | IV | 15 | 48 | + | 31 | 10 | 37 |

| 27 | M | 62 | III | 8 | 54 | + | 34 | 24 | 11 |

| 28 | M | 49 | II | 5 | 44 | + | 10 | 5 | 8 |

| 29 | M | 78 | III | 8 | 70 | + | 66 | 13 | 49 |

| 30 | M | 61 | III | 12 | 49 | + | 57 | 45 | 26 |

| 31 | M | 43 | III | 13 | 30 | + | 51 | 35 | 51 |

| 32 | M | 61 | II | 3 | 58 | + | 76 | 49 | 49 |

| 33 | M | 60 | III | 8 | 52 | + | 62 | 60 | 60 |

| 34 | M | 62 | II | 2 | 60 | + | 24 | 18 | 40 |

| 35 | M | 77 | IV | 17 | 60 | + | 54 | 23 | 81 |

| Mean | 60.5 | N/A | 7.1 | 53.4 | N/A | 51 | 24 | 46 | |

| SD | 9.9 | N/A | 4.3 | 9.6 | N/A | 23 | 22 | 25 | |

S46min[%], radiotracer activity over the gastric area at 46 min; S92min[%], radiotracer activity over the gastric area at 92 min; St1/2, gastric emptying half-time; H&Y, Hoehn&Yahr scale; M, male; F, female; SD, standard deviation; N/A, nonapplicable.

All subjects were on levodopa/benserazide therapy and 17 subjects were also treated with amantadine. No subjects were taking dopamine agonists, MAO-B inhibitors, COMT inhibitors, metoclopramide or domperidone. Patients on any concurrent drug treatment that could potentially impair autonomic nervous system function or gastrointestinal motility were excluded from the study. No subject in the study had a history of major gastrointestinal disease, gastrointestinal surgery (except appendectomy), or concomitant gastrointestinal symptoms and diabetes mellitus.

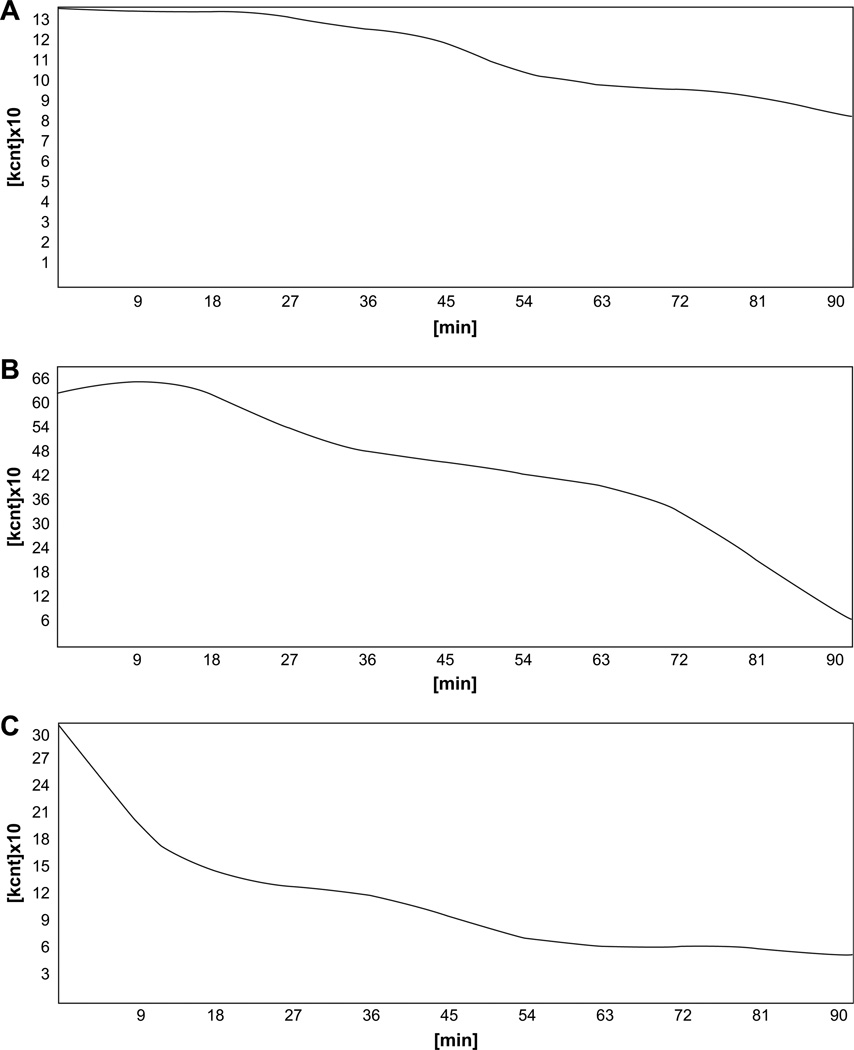

Gastric emptying was estimated by dynamic abdominal scintigraphy started immediately after the complete ingestion of a standardized 200 kcal solid meal containing 99m Tc-labeled colloid of 40 MBq activity. All subjects fasted for at least 8 h prior to the examination, and the time taken to ingest the meal was less than 10 min. Scintigraphy was performed at a rate of 23 images at 4-min intervals for a total of 92 min. Gastric emptying curves were analyzed with the computer program of the gamma-camera ZLC Digitrac 7500 (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) connected to acquisition station Mirage and processed by ICON computer programming. Mean gastric emptying half-time and mean radiotracer activity over the gastric area at 46 min and at 92 min of the procedure were analyzed for both fPD and sPD group. The same parameters of gastric emptying function were assessed in healthy control subjects and the results were compared to those of the fPD and sPD groups. The results of dynamic gastric scintigraphy performed in an individual with fPD, one with sPD, and in a healthy control subject are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The results of dynamic gastric scintigraphy with the use of 99mTc-colloid standard solid meal over 92 min. A, 62-year-old man with familial Parkinson disease; B, 58-year-old man with sporadic Parkinson disease; C, Healthy control subject.

Molecular genetic analysis was performed in all PD subjects. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood and prepared according to standard methods. Genetic studies included screening of the leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) p.G2019S mutation using Taqman chemistry, following the manufacturer’s protocol (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA), screening of the Lrrk2 p.R1441C/G/H substitutions using a restriction enzyme digest (BstU1 enzyme, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), sequencing of 12 exons and intron–exon boundaries of PRKN using Big Dye chemistry (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA), and quantitative analysis of SNCA, PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1), PRKN, DJ1 with SALSA® MLPA® kit P051, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, Netherlands). Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (SCA2) and spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3) genes were also screened for trinucleotide repeat expansions.

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using Statistica 5.1 software (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA). All variables were distributed normally and so are presented as mean ± SD. The normal distribution permitted the use of Student’s t-test for comparisons between groups and Pearson’s test to determine possible correlations between tested variables. Gastric emptying in the PD groups was considered abnormal when prolonged more than two standard deviations above the mean value for controls. Calculated p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Gastric emptying time was delayed in 60% of subjects with PD and was manifested by prolonged gastric emptying half-time or increased gastric retention at 46 or 92 min as compared to data obtained in normal subjects.

When fPD and sPD were examined separately, gastric emptying was found to be delayed in 70% of subjects with fPD and in 55% of subjects with sPD. A statistically significant difference was shown for fPD as compared to controls (p = 0.02). In contrast, the differences in gastric emptying time for the sPD group as compared to controls did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.10).

In the PD study groups, mean gastric emptying half-time was 58 (range 23–92) min in the individuals with fPD (fPDt½) and 46 (range 7–92) min in those with sPD (sPDt½), while the normal value established in healthy individuals was only 38 (range 29–46) min. The mean values of radiotracer activity over the gastric area after 46 min of the test were found to be 64% in fPD (range 10–98, fPD%46min), 51% in sPD (range 1–86, sPD%46min) and 43% in controls (range 31–58). The mean values of radiotracer activity over the gastric area after 92 min were 23% in fPD (range 0–89, fPD%92min), 24% in sPD (range 0–81, sPD%92min) and below 10% in controls. Tables 1a, 1b and 2 show the gastric emptying rates for subjects with fDP and sPD as well as for control subjects.

Table 2.

Gastric emptying rates for patients with familial Parkinson disease (fPD), sporadic Parkinson disease (sPD) and healthy control subjects (controls).

| fPD mean ± SD | sPD mean ± SD | Controls mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| t½ (min) | 58± 25* | 46± 25 | 38.4± 7.3 |

| %46min (%) | 64± 32** | 51± 23 | 43.6± 7.5 |

| %92min (%) | 23± 30 | 24± 22 | 9.5± 6.2 |

%46min, radiotracer activity over the gastric area at 46 min; %92min, radiotracer activity over the gastric area at 92 min; t1/2, gastric emptying half-time;

statistically significant difference in fPD versus controls with p = 0.02;

statistically significant difference in fPD versus controls with p = 0.02;

SD, standard deviation.

Both fPD and sPD groups included cases of impaired gastric emptying at an early stage of disease as defined by H&Yand UPDRS. Demographics and clinical characteristics are presented in Tables 1a and 1b.

Mutation screening, gene sequencing and dosage analysis did not reveal any known genomic abnormality in fPD or sPD subjects.

4. Disscusion

Using dynamic abdominal scintigraphy we have demonstrated that gastric emptying in fPD is significantly delayed when compared to normal gender- and age-matched individuals. These results are in accord with previous studies reporting delayed gastric emptying in PD patients [7,11]. The frequency of delayed gastric emptying in sPD in comparison to controls, although increased, did not reach statistical significance.

Our study is the first to assess gastric emptying specifically in fPD, in which we found impairment tended to be more severe than in sPD, although without reaching statistical significance. This might be because the number of subjects in fPD group was too small to demonstrate significance given the range of gastric emptying variability. It is also possible that fPD represents a more progressive neurodegenerative process in the area of nonmotor impairment. However, it is noteworthy that our fPD group contained three cases in H&Y stage II with disease duration of 14 (2 cases) and 18 (1 case) years.

This study showed that gastric emptying was more delayed in advanced stages of PD, but also that delayed gastric emptying was present in the early stage of PD. The early presence of gastrointestinal dysfunction is in agreement with the study by Djaldetti et al., which found no correlation between disease severity or duration and the presence of impaired gastric motility in PD [11].

The finding that delayed gastric emptying can occur early in PD challenges the traditional understanding that this is a late feature of the disease, as suggested by other studies that found reduced gastric motility correlating with PD duration or severity of motor impairment [13,14,18]. One possible explanation for such correlation is pharmacokinetic, in that delayed gastric emptying may interfere with levodopa absorption and contribute to motor response fluctuations typical of advanced stages of the disease [11,19,20]. However, we did not observe a relationship between any of the gastric empting parameters and the presence of motor fluctuations.

This study assumed that genetic differences might be important. Given that, the conflicting findings of previous studies correlating PD disease duration and severity with gastric emptying might be explained by differences in subject selection that did not discriminate among familial versus sporadic forms of PD.

The early appearance of gastrointestinal dysfunction, even prior to pharmacologic intervention for PD, its persistence during longitudinal follow-up, and correlation in some studies with disease severity indicate a direct relationship between PD pathology and gastrointestinal dysfunction. The underlying basis of gastrointestinal dysfunction in PD appears to involve both central and peripheral mechanisms. Recent neuropathological studies have found that the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus is one of the brain areas affected earliest by α-synuclein pathology [21,22]. Since the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus innervates the myenteric plexus, which in turn governs gastrointestinal motility, these observations point to an anatomic substrate by which autonomic enteric dysfunction may begin at very early stage of PD. Furthermore, virtually all vagal preganglionic projections to the myenteric plexus express α-synuclein, both in their axons and in terminal varicosities reaching myenteric neurons [23]. Postmortem immunohistochemical studies of PD have also detected early pathologic involvement with Lewy bodies in the paravertebral and celiac sympathetic ganglia and in the myenteric and submucosal plexus of the alimentary tract [24–26].

In parallel with our findings, functional cardiac imaging studies have shown that amine uptake is already impaired in postganglionic sympathetic neurons innervating the heart quite early in PD [27–29]. These observations together with a retrospective study that found lower body mass indices years prior to the development of symptomatic parkinsonism [30] strengthen the conclusion that autonomic dysfunction may be an early phenomenon in PD.

A possible limitation of this study was the inability to demonstrate a single genotype characterizing the fPD cohort, which might therefore have been genetically heterogeneous. Although our molecular genetic analysis including mutation screening, gene sequencing and dosage analysis for known parkinsonian genes (LRRK2, SNCA, PRKN, PINK1, DJ1, SCA2 and SCA3) did not show any known genomic abnormality, new still unidentified loci/genes could not be excluded in these families.

In conclusion, gastric emptying is delayed in PD, and especially in fPD. This study further advances the emerging understanding that gastrointestinal symptoms in PD occur early on and likely result from direct involvement of the autonomic and enteric nervous systems by the primary disease process [31]. Further research into the enteric nervous system in PD is warranted. As neuroscience clarifies the molecular pathogenesis of PD, correlation of early autonomic findings with clinical, histopathological and genetic data may provide invaluable insights into the basic mechanisms of onset and progression in fPD and sPD. Moreover, a new understanding of pathogenesis may identify novel targets for the development of models, indicate disease biomarkers, improve the diagnostic process and ultimately lead to novel therapies tailored to the patients.

Acknowledgments

A.K-W is a Consultant on the Morris K. Udall Center of Excellence for PD Research (P50-NS40256). Z.K.W. and M.J.F are supported by the Morris K. Udall Center of Excellence for PD Research (P50-NS40256) and the Pacific Alzheimer Research Foundation (PARF) grant C06-01. B.J-M is supported by the Medical University of Silesia, Poland and the Robert and Clarice Smith Fellowship Program. The authors would like to thank Magdalena Szczerbowska-Boruchowska and Wieslaw Wajs for statistical review. Many thanks to Stephanie Cobb for her technical support. We are grateful to all patients and healthy participants for their collaborations.

Footnotes

The review of this paper was entirely handled by the Co-Editor-in-Chief, Ronald Pfeiffer.

References

- 1.Pfeiffer RF, Quigley EM. Gastrointestinal motility problems in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Epidemiology, pathophysiology and guidelines for management. CNS Drugs. 1999;11(6):435–448. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfeiffer RF. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2(2):107–116. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00307-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siddiqui MF, Rast S, Lynn MJ, Auchus RF, Pfeiffer RF. Autonomic dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: a comprehensive symptom survey. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2002;8(4):277–284. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8020(01)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Idiaquez J, Benarroch E, Roslaes H, Milla P, Rios L. Autonomic and cognitive dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Clin Auton Res. 2007;17(2):93–98. doi: 10.1007/s10286-007-0410-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards LL, Quigley EMM, Pfeiffer RF. Gastrointestinal symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Frequency and pathophysiology. Neurology. 1992;42(4):726–732. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.4.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards LL, Quigley EMM, Harned RK, Hoffman R, Pfeiffer RF. Characterization of swallowing and defecation in Parkinson’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89(1):15–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomaides T, Karapanayiotides T, Zoukos Y, Haeropoulos C, Kerezoudi E, Demacopoulos N, et al. Gastric emptying after semi-solid food in multiple system atrophy and Parkinson disease. J Neurol. 2005;252(9):1055–1059. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0815-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korczyn AD. Autonomic nervous system screening in patients with early Parkinson’s disease. In: Przuntek H, Riderer P, editors. Early diagnosis and preventive therapy in Parkinson’s disease. Vienna: Springer-Verlag; 1989. pp. 41–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashraf W, Pfeiffer RF, Park F, Lof J, Quigley EM. Constipation in Parkinson’s disease: objective assessment and response to psyllium. Mov Disord. 1997;12(6):946–951. doi: 10.1002/mds.870120617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abbott RD, Petrovitch H, White LR, Masaki KH, Tanner CM, Curb JD, et al. Frequency of bowel movements and the future risk of Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2001;57(3):456–462. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.3.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Djaldetti R, Baron J, Ziv I, Melamed E. Gastric emptying in Parkinson’s disease: patients with and without response fluctuation. Neurology. 1996;46(4):1051–1054. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.4.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards L, Quigley EM, Hofman R, Pfeiffer RF. Gastrointestinal should be symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. 18 month follow-up study. Mov Disord. 1993;8(1):83–86. doi: 10.1002/mds.870080115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krygowska-Wajs A, Lorens K, Thor P, Szczudlik A, Konturek S. Gastric electromechanical dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Funct Neurol. 2000;15(1):41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goetze O, Wieczorek J, Mueller T, Przuntek H, Schmidt WE, Woitalla D. Impaired gastric emptying of a solid test meal in patients with Parkinson’s disease using 13C-sodium octanoate breath test. Neurosci Lett. 2005;375(3):170–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein DS, Li ST, Kopin IJ. Sympathetic neurocirculatory failure in Parkinson disease: evidence for an etiologic role of alpha-synuclein. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(11):1010–1011. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-11-200112040-00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singleton A, Gwinn-Hardy K, Sharabi Y, Li ST, Holmes C, Dendi R, et al. Association between cardiac denervation and parkinsonism caused by alpha-synuclein gene triplication. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 4):768–772. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orimo S, Amino T, Yokochi M, Kojo T, Uchihara T, Takahashi A, et al. Preserved cardiac sympathetic nerve accounts for normal cardiac uptake of MIBG in PARK2. Mov Disord. 2005;20(10):1350–1353. doi: 10.1002/mds.20594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwards LL, Pfeiffer RF, Quigley EM, Hofman R, Balluf M. Gastrointestinal symptoms in Parkinson’s. Mov Disord. 1991;6(2):151–156. doi: 10.1002/mds.870060211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goetze O, Nikodem AB, Wieczorek J, Banasch M, Przuntek H, Mueller T, et al. Predictors of gastric emptying in Parkinson’s disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18(5):369–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muller T, Erdmann C, Bremen D, Schmidt WE, Muhlack S, Woitalla D, et al. Impact of gastric emptying on levodopa pharmacokinetics in Parkinson disease patients. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2006;29(2):61–67. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200603000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rub U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(2):197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braak H, Bohl JR, Muller CM, Rub U, de Vos RA, Del Tredici K. Stanley Fahn Lecture 2005: the staging procedure for the inclusion body pathology associated with sporadic Parkinson’s disease reconsidered. Mov Disord. 2006;21(12):2042–2051. doi: 10.1002/mds.21065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillips RJ, Walter GC, Wilder SL, Baronowsky EA, Powley TL. Alpha-synuclein-immunopositive myenteric neurons and vagal preganglionic terminals: autonomic pathway implicated in Parkinson’s disease? Neuroscience. 2008;153(3):733–750. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wakabayashi K, Takahashi H, Ohama E, Takeda S, Ikuta F. Lewy bodies in the visceral autonomic nervous system in Parkinson’s disease. Adv Neurol. 1993;60:609–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braak H, de Vos RA, Bohl J, Del Tredici K. Gastric alpha synuclein immunoreactive inclusions in Meissner’s and Auerbach’s plexuses in cases staged for Parkinson’s disease-related brain pathology. Neurosci Lett. 2006;396(1):67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wakabayashi K, Takahashi H, Omaha E, Ikuta F. Parkinson’s disease: an immunohistochemical study of Lewy body-containing neurons in the enteric nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 1990;79(6):581–583. doi: 10.1007/BF00294234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldstein DS, Holmes C, Li ST, Bruce S, Metman LV, Cannon RO., 3rd Cardiac sympathetic denervation in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(5):338–347. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-5-200009050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldstein DS. Cardiac sympathetic denervation preceding motor signs in Parkinson disease. Clin Auton Res. 2007;17(2):118–121. doi: 10.1007/s10286-007-0396-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshita M. Differentiation of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease from striatonigral degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy using iodine-123 meta-iodobenzylguanidine myocardial scintigraphy. J Neurol Sci. 1998;155(1):60–67. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(97)00278-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheshire WP, Wszolek ZK. Body mass index is reduced early in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2005;11(1):35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaufmann H, Nahm K, Purohit D, Wolfe D. Autonomic failure as the initial presentation of Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2004;63(6):1093–1095. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000138500.73671.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]