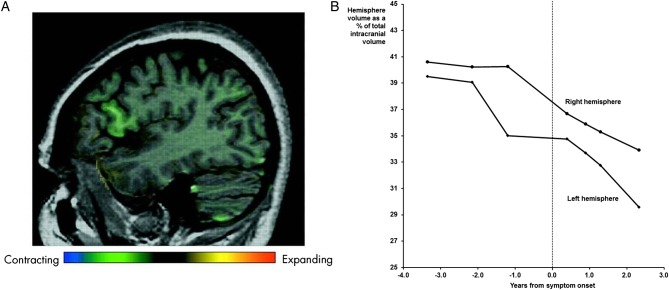

In 2005, we reported a case of familial primary progressive aphasia (PPA) in this journal.1 The individual in question had a family history of frontotemporal dementia (FTD), her brother having behavioural variant FTD shown to be due to tau-negative, ubiquitin-positive (FTLD-U) pathology at postmortem. She was followed as part of a research programme from the age of 51 years, first developing symptoms of progressive speech disturbance at the age of 55 years. We were able to demonstrate the emergence of neuropsychometric deficits and brain atrophy prior to symptom onset. Through the use of voxel compression mapping, we showed the emergence of very focal, presymptomatic regional atrophy initially almost entirely confined to the pars opercularis (figure 1A).1 Over time, the atrophy spread through the frontal and temporal lobes to affect the parietal lobe and then the right frontal lobe. Subsequent analysis has shown increase in left and right hemispheric lobar atrophy prior to symptom onset, although the left hemisphere volume loss preceded and remained more prominent than the right throughout the disease course (figure 1B).

Figure 1.

MRI changes in the proband: (A) sagittal MRI showing focal anterolateral left frontal lobe atrophy, particularly centred around the pars opercularis, using voxel compression mapping between the first and second scans (3.4 and 2.1 years prior to symptom onset) (reprinted from Janssen et al,1; (B) changes in left and right hemispheric volume over time.

At the time of publication, mutations in the microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) were the only known genetic cause of disorders within the FTD spectrum, and screening for MAPT mutations was negative. Since then, the progranulin (GRN) and C9ORF72 genes have been shown to be major causes of familial FTD.2 Her brother's pathology was subsequently reanalysed and reclassified as FTLD-transactive response DNA-binding protein (TDP) type A pathology,3 consistent with either a GRN or C9ORF72 mutation. However, conventional analyses failed to disclose mutations in either of these genes in this family.4–6

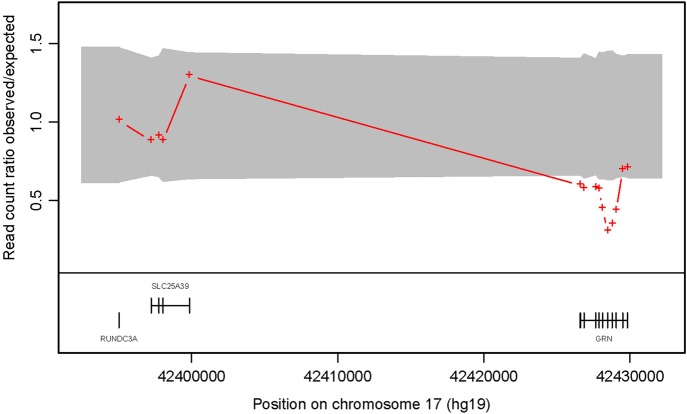

In order to investigate this further, DNA from her brother underwent exome sequencing, performed on genomic DNA using Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon v2 target enrichment kit. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq2000 and achieved an average 30-fold depth-of-coverage of target sequence.7 ExomeDepth8 compares the read depth data between a test sample and an aggregate reference set that combines multiple exomes matched to the test sample for technical variability (Software freely available at: http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ExomeDepth/index.html). Analysis demonstrated a GRN gene deletion. The red crosses (figure 2) show the ratio of observed/expected number of reads for the test sample. The grey shaded region shows the estimated 99% CI for this observed ratio in the absence of copy number variation (CNV) call. The presence of contiguous exons with read count ratio located outside of the CI is indicative of a heterozygous deletion in the GRN gene. GRN exons 0, 2, 5, 9 and 11 were subsequently probed for copy number variation using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) analysis with the Medical Research Council (MRC) Holland kit P275, which is routinely used for assessing GRN deletions.9 10 This confirmed the presence of a novel heterozygous deletion of exons 2–11. Test results show the 5′ untranslated region of the gene was present, but could not determine if exon 12 of GRN was also deleted. The same deletion was detected in the proband using MLPA analysis.

Figure 2.

The read count ratio of observed to expected is shown plotted against position in basepairs along chromosome 17. A reduction in read count ratio to 0.5 and below at the GRN locus can be seen, and indicate a heterozygous gene deletion.

While progranulin mutations were not known to cause frontotemporal lobar degeneration at the time of our original report, the clinical features that emerged during the course of her illness would now be recognised as being fairly characteristic. Progranulin mutations are usually associated with behavioural variant FTD or PPA,2 3 with combinations of these presentations recognised within the same family. Neuropsychologically, patients often have executive dysfunction and early parietal lobe deficits, with PPA patients having a non-fluent aphasia with a prominent anomia. Imaging studies in patients with established disease typically show prominent asymmetrical atrophy affecting frontal, temporal and parietal lobes consistent with neuropsychological findings.11 Finally, the pathology, type A TDP-43, would be consistent with that seen in progranulin mutations (and also C9ORF72 expansions).2 3

This case serves to illustrate a number of important points. First, progranulin mutations should always be considered as a cause of PPA where there is a positive family history either of PPA or behavioural variant FTD. Second, prominent asymmetric lobar atrophy on MRI is an important clue to the presence of a progranulin rather than a MAPT or C9ORF72 mutation in the context of an autosomal-dominant family history. Third, as with other neurodegenerative diseases, this case shows that focal brain atrophy precedes symptom onset in genetically determined forms of FTD; rates of atrophy may therefore be useful outcome measures for presymptomatic therapeutic trials in these disorders. Finally, the fact that conventional progranulin testing was negative in this case demonstrates the power of exome sequencing as a tool to discover large-scale mutations, such as the partial deletion seen here, that may not be found with usual screening methods for small-scale changes.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Medical Research Council UK. The Dementia Research Centre is an Alzheimer's Research UK Co-ordinating Centre and has also received equipment funded by Alzheimer's Research UK and Brain Research Trust. JR is an NIHR clinical lecturer, MR and NF are NIHR senior investigators, JDW is supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Clinical Fellowship, and are researchers at the NIHR Queen Square Dementia BRU. JS is an NIHR Clinical Senior Lecturer. This work was supported by the NIHR Queen Square Dementia BRU.

Footnotes

Contributors: JDR wrote the draft of the manuscript and analysed the imaging data. JB, VP and SM performed the genetic analyses. TL and TR performed the pathological analyses. EG performed imaging analyses. JCJ, JMS, MNR, JDW and NCF performed patient evaluation. All authors reviewed and contributed to the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery Local Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Janssen JC, Schott JM, Cipolotti L, et al. Mapping the onset and progression of atrophy in familial frontotemporal lobar degeneration. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005;76:162–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rohrer JD, Warren JD. Phenotypic signatures of genetic frontotemporal dementia. Curr Opin Neurol 2011;24:542–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rohrer JD, Lashley T, Schott JM, et al. Clinical and neuroanatomical signatures of tissue pathology in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Brain 2011;134 (Pt 9):2565–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beck J, Rohrer JD, Campbell T, et al. A distinct clinical, neuropsychological and radiological phenotype is associated with progranulin gene mutations in a large UK series. Brain 2008; 131 (Pt 3):706–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rohrer JD, Guerreiro R, Vandrovcova J, et al. The heritability and genetics of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology 2009;73:1451–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mahoney CJ, Beck J, Rohrer JD, et al. Frontotemporal dementia with the C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion: clinical, neuroanatomical and neuropathological features. Brain 2012;135 (Pt 3):736–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sergouniotis PI, Davidson AE, Mackay DS, et al. Biallelic mutations in PLA2G5, encoding group V phospholipase A2, cause benign fleck retina. Am J Hum Genet 2011;89:782–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Plagnol V, Curtis J, Epstein M, et al. A robust model for read count data in exome sequencing experiments and implications for copy number variant calling. Bioinformatics 2012;28:2747–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gijselinck I, van der Zee J, Engelborghs S, et al. Progranulin locus deletion in frontotemporal dementia. Hum Mutat 2008;29:53–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Skoglund L, Ingvast S, Matsui T, et al. No evidence of PGRN or MAPT gene dosage alterations in a collection of patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2009;28:471–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rohrer JD, Ridgway GR, Modat M, et al. Distinct profiles of brain atrophy in frontotemporal lobar degeneration caused by progranulin and tau mutations. Neuroimage 2010;53:1070–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]