Abstract

Objectives

Our aim is to describe the growth and staffing structure of a palliative care program at a comprehensive cancer center.

Methods

During fiscal years (FYs) ending in 2000 through 2010, we recorded all billed palliative care consultations and follow-ups. In order to determine the yearly clinical burden per physician, advanced practice nurse (APN) and physician assistant (PA), we calculated the mean number of patient encounters per clinical full time equivalents. Increase in absolute number of patient encounters and relative (%) growth from year to year were calculated.

Results

Over the 10 year history of the program, the number of outpatient consultations tripled while inpatient consults increased from 73 to 1880. In all cases, with the exception of the 1st year of operation, the vast majority of clinical activity was in the inpatient hospital setting. Growth in the ratio of inpatient consultations per operational hospital beds was noted during the first 5 years of the program, followed by a more modest increase in the succeeding 5 years. In FY 2010, palliative care physicians had 6.2 patient encounters per working day, and APN/PAs, independently evaluated and treated 4.0 additional patients.

Conclusion

Over the 10 year history, there has been an increase in the number of patient consultations seen by our palliative care program. The clinical burden was manageable during the first 3 years but quickly became too burdensome. Active recruitment of new faculty was required to sustain the increased clinical activity.

Keywords: Palliative care, program development, workforce staffing, supportive care

Introduction

The World Health Organization defines palliative care as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual.” Clinicians trained in palliative medicine provide coordinated, interdisciplinary care for patients with life-threatening illnesses. Factors that include an aging population, an increase in complex chronic illnesses, and advances in medicine allowing for a longer life expectancy have culminated in greater recognition of the value of palliative care.

In response to the increased need, cancer centers as well as other health care organizations have developed palliative care programs in academic and community settings, resulting in dramatic growth of the specialty [1]. The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, has been cited [2] as an example of an institution that has integrated palliative care into both the inpatient and outpatient settings. However, the scope of services and the extent of integration of palliative care vary widely among cancer centers [3]. We have previously published articles on the clinical characteristics of the patients referred to our palliative care consultation service [4–6], the impact on patient mortality [7], and outcomes in adult [8, 9] and pediatric [10] cancer patients, as well as the predictors of access [11] and referral patterns [12] of our program. In addition, survival and discharge outcomes [13], predictors of inpatient mortality [14], and financial outcomes [15] of our acute Palliative Care Unit (PCU) also have been published.

Information regarding the challenges of clinical growth [16–18] and staffing allocation [19–21] of palliative care programs is limited. Here we describe the growth and staffing structure of an integrated palliative care program comprising an inpatient PCU, a mobile consult service, and an outpatient supportive care clinic at a comprehensive cancer center over a 10-year period.

Methods

Setting

At the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, the palliative care program includes an interdisciplinary team consisting of full-time palliative care physicians, nurses, advanced practice nurses (APNs), physician assistants (PAs), a social worker, psychiatric nurse counselors, physical and occupations therapists, a case manager, and a chaplain. Care is provided in an acute inpatient PCU, mobile consultation services available throughout the hospital, and an outpatient supportive care clinic.

The M. D. Anderson Cancer Center is a National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center with, on average, 569 operational beds as of the year 2010. In 2003, a dedicated 12-bed acute PCU was opened. The PCU is staffed by an interdisciplinary team consisting of a full-time palliative care physician, palliative care fellow in training, a rotating oncology fellow, an APN or PA, a dedicated palliative care pharmacist, a chaplain, a social worker, a case manager, occupational and physical therapists, four dedicated registered nurses and two nursing aides. A total of 18 nurses, trained and evaluated over a period of six weeks for their ability to manage psychosocial distress in patients and families, are available to provide care in the PCU.

The mobile palliative care consultation service has grown from one team, established in 1999, to three independent teams, each consisting of a palliative care physician, a palliative care fellow, and an APN or PA. A child life counselor, psychiatric nurse, and a chaplain also are available for consultation on a case-by-case basis to assist with patient care. Urgent consultations are provided within four hours, whereas routine consultations are completed within a maximum of 24 hours, with the majority completed the same day.

In 1999, the supportive care clinic included five patient exam rooms; in the year 2000, it was relocated to a larger facility, expanding to eight patient exam rooms and two consultation rooms. Patients are seen by an interdisciplinary team including a palliative care physician, a palliative care-trained registered nurse, a pharmacist, and a nutritionist. If needed, a psychiatric counselor, chaplain, and wound care nurse are available to assess patients and provide recommendations.

In addition to clinical care, the palliative care program conducts a number of scholarly activities including research and education of health care providers within the institution and in the community. An ACGME-accredited hospice and palliative medicine fellowship program trains five physicians per year. In addition, all faculty and staff in palliative care participate in weekly grand rounds, weekly morning lectures for fellows, and half-hour journal club sessions three days a week; faculty members also rotate through monthly half-day bus rounds [22]. The department hosts an annual board review and educational conference lasting one week. Currently, all faculty members participate in research and the department is actively conducting approximately 18 clinical trials per year and completing 50 major peer-reviewed publications per year.

In a given year, full-time clinical faculty will be assigned to approximately eight months of consult service and one month in the PCU. In addition, faculty members are assigned to provide coverage in the supportive care clinic one day per week, and rotate after hours and weekend call coverage on a weekly basis. APNs and PAs are assigned nine months of consult service and three months in the PCU, and provide clinical care during working hours.

Approval to conduct the study was obtained from the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board.

Procedures

Financial data were extracted corresponding to the institution’s fiscal year (FY), starting from the 1st of September of the preceding year and ending the 31st of August of the next year. For each FY, ending in 2000 through 2010, we recorded all billed palliative care consultations, inpatient as well as outpatient, and billed follow-ups seen by our interdisciplinary team. Follow-up visits were divided into encounters either seen solely by a palliative care physician or co-managed with an APN or PA, and visits billed separately by these providers were noted.

In order to determine the yearly clinical burden per clinician or APN/PA, we calculated the mean number of patient encounters per clinical full-time equivalents (FTEs). Clinical FTEs for palliative care physicians and APN/PAs were determined by reviewing the percentage of time dedicated to patient care as opposed to research. For example, an academic palliative care physician who contributes 30% of his FTE to clinical care would be assigned a value of 0.3 FTE [23]. FTEs for other members of the interdisciplinary team also were assigned, including the chaplain and psychiatric nurse counselors.

The Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC), a national organization dedicated to improving access to palliative care services in the U.S., has provided operational training and mentoring for professionals establishing hospital-based palliative care programs and hospices. Recommendations by CAPC estimate a linear growth of new patient encounters in the hospital setting: the first year of operation equivalent to 0.5–1.0 new consultation per staffed hospital bed; third year 1.0–1.5 new consults per staffed hospital bed; and fifth year 1.5–2.0 new consults per staffed hospital bed. In order to test these predictors of growth in clinical activity, we determined the number of billed inpatient consultations and the number of operational beds per year during 2000 through 2010.

In this study, we report data for each year of operation as absolute number of patient encounters. Growth was determined as both an increase in absolute number of encounters as well as relative (%) growth – from one fiscal year relative to the previous fiscal year. Also, to determine the extent of integration of palliative care into cancer treatment at our center, the total number of cancer patients seen and the proportion of these patients referred to palliative medicine for the year 2010 were calculated. Because of the nature of the study, only descriptive statistics were used.

Results

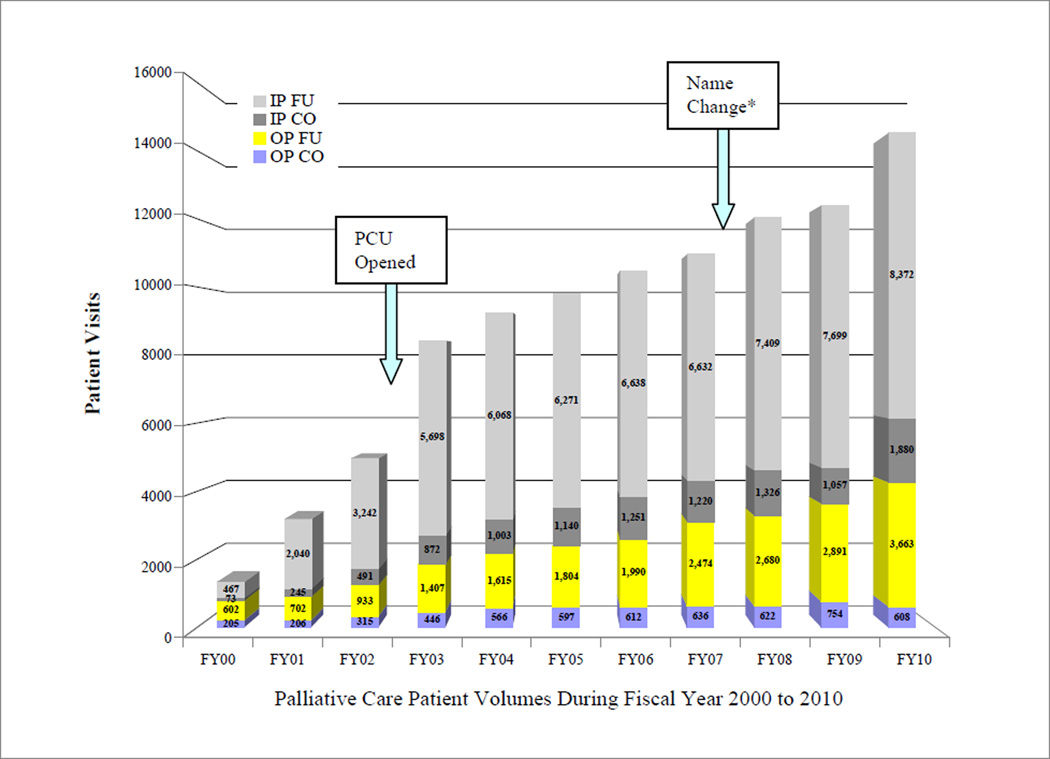

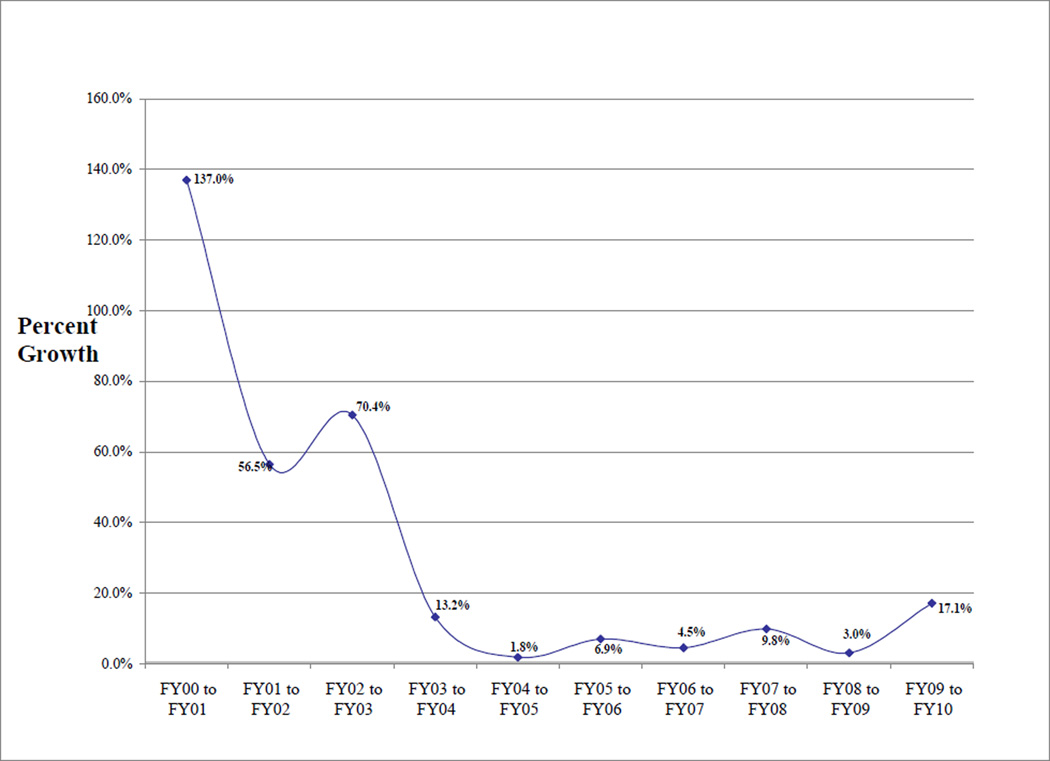

In FY 2010, our institution evaluated 17,878 cancer patients, of which 799 (4.5%) were referred to the palliative medicine service. In the first FY of the program, there were a total of 205 consultations in our outpatient supportive care clinic, and only 73 inpatient consultations occurred (Fig. 1). Of note, the FY of 2000 was the only year there were more outpatient than inpatient consultations. Figure 1 shows a consistent growth of clinical encounters from FY 2000 to 2010; however, both Figs. 1 and 2 reveal a steeper increase in number of patient visits during the initial four-year history of the palliative care program and a subsequent stable plateau during the fourth and eighth FYs. FY 2009 saw the least growth as a whole and was followed by a rebound in clinical growth in FY 2010.

Figure 1.

Growth of Palliative Care Clinical Encounters from Fiscal Year 2000 to 2010.

IP – Inpatient; OP – Outpatient; CO – Palliative Care Consultation; FU- Follow-up clinical visit; PCU – Palliative Care Unit; *Name change (Supportive Care from Palliative Care)

Figure 2.

Year to Year Growth in Patient Encounters in a Palliative Care Program from Fiscal Year (FY) 2000 to 2010.

In FY 2010, 608 new outpatient consultations and 3663 follow-up appointments took place in our supportive care clinic, and 1880 consultations and 8372 follow-up visits took place in the inpatient hospital setting (Fig. 1). Over the 10-year history of the program, the number of outpatient consultations tripled, and the inpatient setting saw an increase from 73 to 1880 palliative care consults. In all cases, with the exception of the first year of operation, the vast majority of clinical activity was in the inpatient hospital setting. Over the past five years, in the inpatient setting the ratio of consults to follow-up visits has been consistent, averaging 1:5.6, whereas the ratio in the outpatient clinic has increased from 1:3.2 for FY 2006 to 1:6.0 for FY 2010.

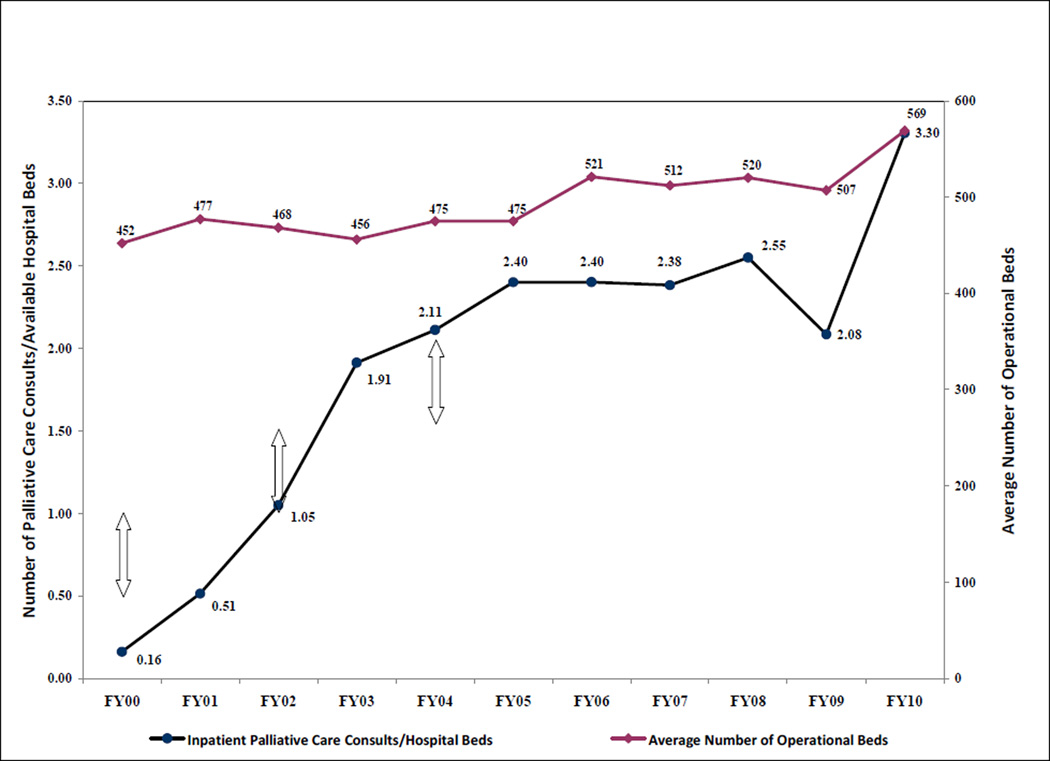

Figure 3 shows the ratio of inpatient consultations seen in relation to the available hospital beds. Sustained growth in the ratio of number of inpatient consultations per operational hospital beds was noted during the first five years of the program, followed by a modest increase in the number of consultations the succeeding five years.

Figure 3.

Palliative Care Inpatient Consultations Per Average Number of Operating Beds from Fiscal Year 2000 to 2010.

Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) estimated growth indicated by arrows.

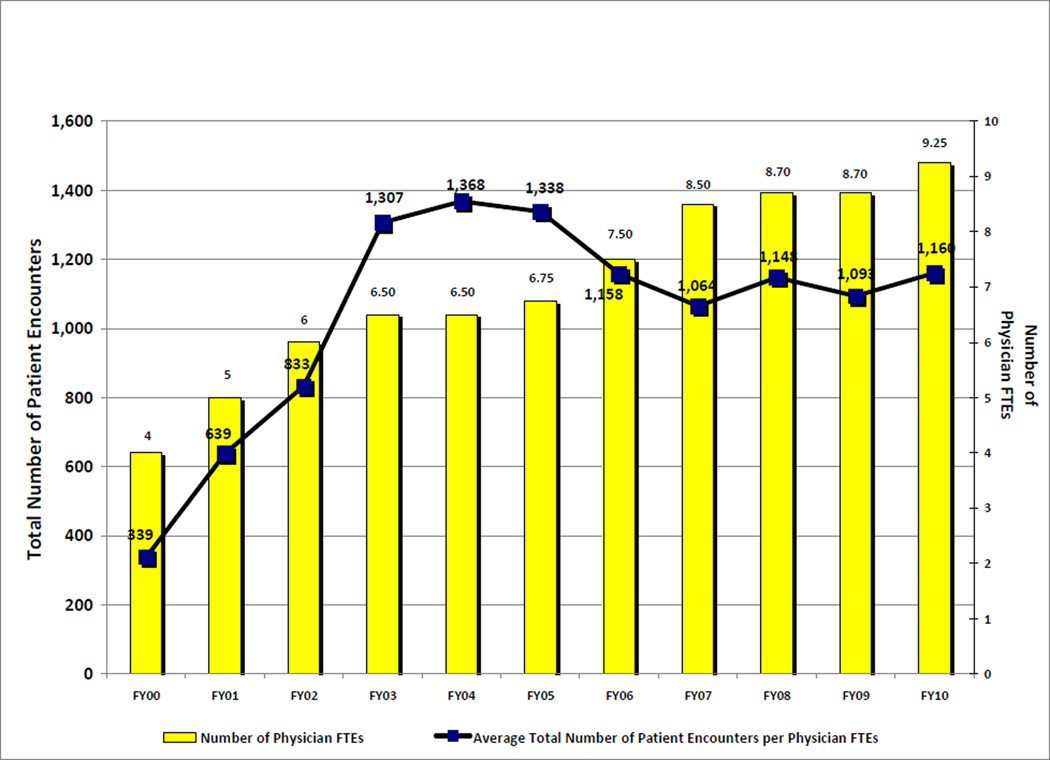

Patient encounters billed per physician clinical FTE are noted in Fig. 4. There was an increase in encounters per FTE the first five fiscal years, consisting of an initial gradual increase in workload the first three FY, followed by three years of high clinical burden in FYs 2003 to 2005, and subsequently a drop in workload resulting in a steady ratio of encounters per FTE ranging from 1064 to 1160 during the last five years. In FY 2010, based on 187 standard working days, on average, palliative care faculty made 6.2 patient encounters either independently or co-managed with an APN/PA per working day.

Figure 4.

Average Inpatient and Outpatient Activity per Full Time Physician Equivalents (FTE) from the Fiscal Year 2000 to 2010.

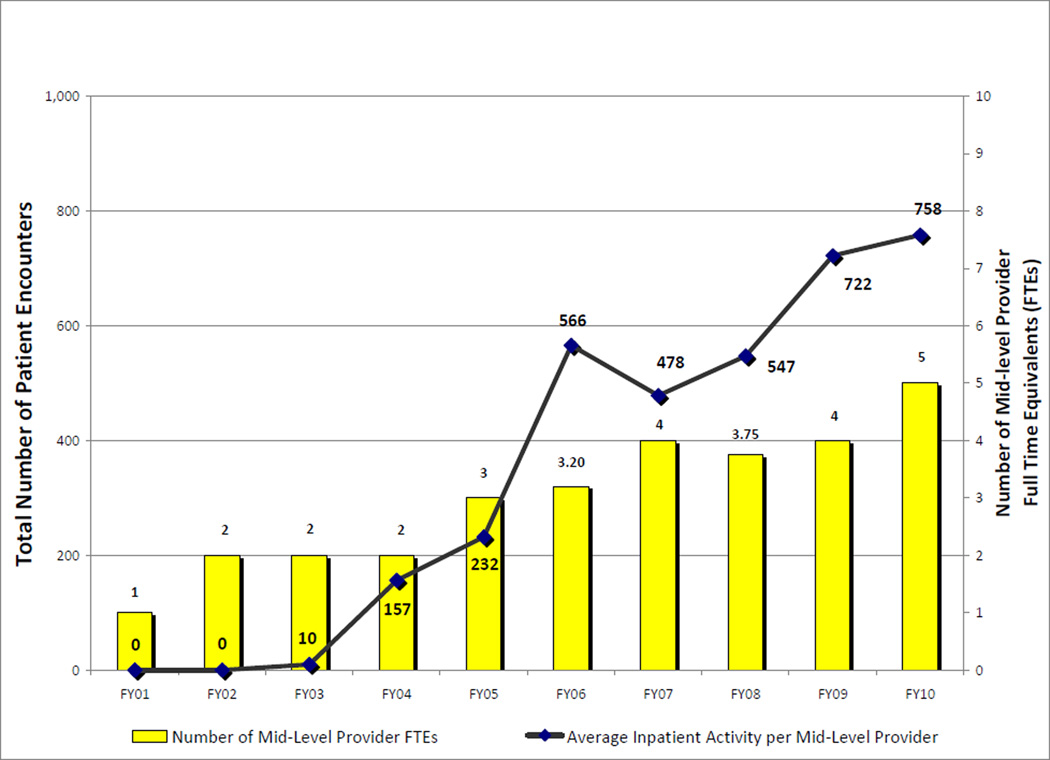

Figure 5 reports patient encounters seen independently by APNs/PAs in addition to the ones they co-managed with physicians. In the first three FYs, APNs/PAs infrequently saw patients independently. Starting in FY 2004, independent patient encounters by APNs/PAs show a steady increase through FY 2010. In FY 2010, APNs/PAs, working, on average, 190 days, independently evaluated and treated 4.0 patients.

Figure 5.

Average Inpatient Activity per Full Time Mid-level Provider Equivalents from Fiscal Year 2000 to 2010.

Table 1 describes the distribution of disciplines of the interdisciplinary palliative care team during the inception, midway, and year 2010 of the program. For the chaplain, pharmacist, and psychiatric nurse/child life counselors, a value of 0 means that the discipline is available as a part of the hospital staff upon request. A value of ≥ 1 reflects FTE participation as a member of the interdisciplinary team.

Table 1.

Description of the Interdisciplinary Team at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center’s Palliative Care Program

| Description of Palliative Care Provider (FTE) |

2001 | 2005 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palliative Care Physicians | 4 | 6.75 | 9.25 |

| Mid-Level Providers | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| Social Workers | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Chaplain | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Pharmacist | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Psychiatric Nurse Counselors/Child Life | 0 | 1 | 2 |

FTE = full-time equivalent; mid-level providers = advanced practice nurse or physician assistant

Table 2 reports the duration of key components in an initial palliative care consultation in our supportive care clinic, based on the observation of 100 consultations. In recent years, roughly 80% of scheduled patients are seen, whereas 20% of patients are unable to attend and are often replaced by same-day or walk-in visits, resulting in faculty averaging two to three consults and eight to nine follow-up visits per day.

Table 2.

Duration for Components of a Palliative Care Consultation

| Component | Duration (minutes) |

|---|---|

| Review of Electronic Records | 10 |

| Symptom Assessment and Management | 25 |

| Psychosocial support/decision making | 25 |

| Physical Examination | 5 |

| Discussion with IDT members | 20 |

| Dictation | 10 |

| Advance Care Planning Session (patient and caregiver) | 30 |

| Hospice Discussion & Referral | 30 |

| Family Conference | 45 |

| Inpatient Admission from Supportive Care Clinic | 30 |

| Research Study | 30 |

| Total Duration of Initial Consultation | 45 – 95a |

IDT = interdisciplinary team.

Depending on which components are implemented.

Discussion

Over a period of 10 years, there was consistent growth in clinical activity from year to year (Figs. 1 and 2). However, when factoring against clinical resources, the growth in workload for clinicians was non-linear (Fig. 4). In the initial FYs 2000 to 2002, the workload burden for physicians was low and quite manageable. Clinical activity continued to grow, resulting in a non-sustainable workload for faculty noted in FYs 2003 to 2005. Of note, during the FYs 2003 and 2005, a total turnover of three palliative care physicians occurred, exacerbating the clinical burden for the remaining faculty. Only after the successful recruitment of additional full-time faculty during the subsequent five years, FYs 2006 to 2010, did the clinical workload stabilize between 1000–1200 encounters/FTE. Our experience would strongly suggest that the successful implementation of a palliative care program results in manageable growth initially, followed by a non-sustainable increase in clinical activity that only stabilizes with aggressive recruitment of additional clinical faculty.

The growth of palliative care at our institution, with its unique characteristics, may differ from other academic centers or community health care organizations. At our institution, growth of inpatient consultations for palliative care per operational beds increased each year, with the exception of fiscal year 2009 (Fig. 3). The first year of operation was less than CAPC estimates, 0.16 new consultations per staffed hospital bed, whereas in the third year, inpatient consultations fell within their estimates at 1.05, and the fifth year exceeded estimates, 2.11 consults/bed ratio (Fig. 3).

Factors influencing consult volume as outlined by CAPC include the hospital size and type; degree of acceptance of palliative care and awareness of the specialty; availability and timeliness of palliative care consultation; and degree of internal support and funding from the hospital administration [24]. At M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, palliative care was initially met with stiff resistance by detractors. Adopting a strategy to engineer growth [25] by initially focusing on, and winning over, a small core of early adopters and advocates for palliative care eventually led, and continues today, to the adoption by others who were initially reluctant. Often, early adopters who were supportive were encouraged to persuade detractors to consider the utilization of palliative care providers. Referral patterns at our institution revealed that growth was consistent across all tumor types; however, access to palliative care was earlier for solid tumors than for hematological malignancies [6].

In addition, the availability of an acute PCU or an inpatient hospice facility, the breadth of services provided by a palliative care consulting group (i.e., child life experts, family therapy counselors), and the number of consultant groups providing overlapping services with the field of palliative care, i.e. psychiatry and pain medicine, can potentially influence the number of consultations.

Other factors, including the adoption of a new name, from palliative care to supportive care, for the consult service and the outpatient clinic, may have contributed to our growth. In an anonymous survey of a random sample of 100 medical oncologists and 100 APNs, the name supportive care was preferred to palliative care. The name palliative care was perceived as a barrier to referral by decreasing hope and increasing distress in patients and families [26]. The name change was associated with a 41% increase in the number of new inpatient consults and a median of 1.5 months earlier referral to the outpatient center [27].

Finally, the institutional infrastructure and resources allocated to a palliative care program, including the number of exam rooms and workspace for personnel, can limit a program’s growth. At our institution, the number of consults to our outpatient supportive care clinic has increased during the first five years and subsequently has been limited by lack of infrastructure and personnel to accommodate new patient visits, resulting in the doubling of ratio of follow-up visits to new consultations. One solution attempted to extend the interval between follow-up visits in order to allow for increased access for new patients; however, clinical care for patients who are often chronically ill requires frequent follow-up appointments and the supportive care clinic noted increased walk-in visits of distressed patients and families, which may result in burnout for the staff.

Table 1 describes the workforce that comprises the interdisciplinary team at our institution. On average, a 2:1 ratio of palliative care physicians to mid-level providers has been established in our program. Others have reported a ratio of 1:2 physicians to mid-level providers in a functional palliative care program [16], and variations in staffing, including an expanded role for counselors, has been reported [21]. The National Quality Forum recommends that palliative programs “provide access to palliative and hospice care that is responsive to the patient and family 24 hours a day, 7 days a week” [28]. Providing a fully staffed interdisciplinary team and full-time palliative care physicians available on weekends and after hours can be a daunting task and creative work schedules should be explored to maximize access for patients to palliative care without depleting scarce resources. Since the inception of our program, 24 hours a day/seven days a week coverage has been provided by faculty who have been required to cover after hours and weekends on a rotational basis. This constant coverage was taxing for faculty when their numbers were low. In order to prevent faculty burnout, the program has actively recruited palliative care physicians, resulting in double the ratio of faculty to APNs/PAs. In addition, all faculty members are expected to participate in research and the education of fellows, which can only be pursued if more than adequate numbers are maintained to provide 24/7 clinical coverage. Of note, attracting new faculty has been challenging and the majority of clinicians who have been hired also were trained as fellows within the institution.

In FY 2010, APNs/PAs allowed for roughly four additional patient encounters, which is similar to other groups [19]; however, in the preceding years, APNs/PAs treated fewer patients independently. Of note (Fig. 5), during the first three years in which APNs and PAs participated in providing clinical care, very few patients were seen independently and their role involved co-managing complex, critically ill patients with physicians, including assessment and formulating a treatment plan during initial consultation. As a consequence of increased clinical activity in the later years, APNs/PAs subsequently were employed to provide independent clinical care primarily for follow-up visits and continued to provide back-up support for the faculty for consultations. APNs and PAs provide handoffs at the start and end of the day on a daily basis with faculty.

Future studies are needed to examine the ideal composition of an interdisciplinary palliative care team, evaluating not just growth but also indicators of clinical performance including: clinical outcomes; disposition (i.e., enrollment into hospice); satisfaction of consulting health care providers, patients, and families; and the financial impact for the institution. In addition, preliminary studies [29] of the optimal setting (i.e., consultation teams versus inpatient units) in which palliative care should be delivered, the relative workload in a PCU, consult service, and outpatient palliative care clinic, and the impact of non-billable members of the interdisciplinary team (chaplains, social workers, counselors, child life experts, and others) on the capacity of the clinical team to improve access to and effectiveness of palliative care needs to be explored.

Earlier referral and integration of palliative care into the treatment of patients with life-limiting illnesses have been advocated [30–32]. The benefits of early referral including improved quality of life and prolonged survival have recently been shown in patients with lung cancer [33]. At our institution, only 799/17,878 (4.5%) of new cancer patients were referred to palliative care, indicating a potential for further dramatic growth if early referral to palliative care is adopted. Arguably, care provided prior to and during the emotional transition of patients and their families from curative treatment to palliative care can be more challenging than care provided after. In addition, the cost savings, which have been demonstrated by inpatient palliative care consultation programs [34], may be more substantial and effective when palliative care interventions are implemented earlier for patients with life-limiting illnesses. For full integration of palliative care at the time of diagnosis, additional resources are needed to establish viable outpatient palliative care centers that can accommodate these visits. In anticipation of future growth at our institution, the program has requested additional resources for palliative care including the hiring of more faculty and APNs or PAs; however, secondary to the economic climate and changes in the health care system, there remains a level of uncertainty.

Despite the growth of palliative care programs, considerable variability among programs in the U.S. exists [3]. Cancer centers may require more or less support than other programs existing in traditional medical centers. Also, palliative care interventions with a wide degree of heterogeneity [35] or which lack an interdisciplinary team [36] have been shown to have limited clinical effectiveness as compared to usual care. Institutions where there is a strong primary care physician base, who participate in certain aspects of end-of-life care including family meetings, discharge planning, and coordination of care, would place palliative care providers in a secondary, more supportive role. In these institutions, a palliative care interdisciplinary team may be consulted on a more selective basis and may require fewer resources. In addition, a high-quality palliative care program as outlined by the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine [37] would extend involvement of an interdisciplinary team into the home setting, either by providing home care or hospice care, which would require additional resources. Currently, at our institution, patients are referred to independent hospice agencies or private home care agencies.

Conclusion

Over the 10-year history of our program, there has been consistent growth in clinical activity. However, when factoring in the available workforce of palliative care physicians, the first five years reveals a manageable workload. During the subsequent years, with continued growth, the clinical burden became taxing and required recruitment of additional clinical faculty and staff for the workload to become sustainable. The CAPC repeatedly advises to “plan for growth” and palliative care programs must heed the warning by actively recruiting and expanding the clinical workforce as well as the physical infrastructure to accommodate increased patient encounters. In addition, growth in itself may not be advantageous without accompanying improvements in indicators of quality including clinical and financial outcomes. Future studies are needed to examine the operational metrics of successful academic and community palliative care programs.

Acknowledgments

Eduardo Bruera is supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants RO1NR010162-01A1, RO1CA1222292.01, and RO1CA124481-01. Egidio Del Fabbro is supported in part by an American Cancer Society grant PEP-08-299-01-PC1.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Center to Advance Palliative Care. Hospital palliative care programs continue rapid growth. [Accessed August 29, 2011]; Available from http://www.capc.org/news-and-events/releases/items/december-2006-release. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferris F, Bruera E, Cherny N, et al. Palliative cancer care a decade later: accomplishments, the need, next steps - from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3052–3058. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M, et al. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA. 2010;303:1054–1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yennurajalingam S, Zhang T, Bruera E. The impact of the palliative care mobile team on symptom assessment and medication profiles in patients admitted to a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2007;14(5):471–475. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhillon N, Kopetz S, Pei BL, et al. Clinical findings of a palliative care consultation team at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):191–197. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fadul NA, El Osta B, Dalal S, Poulter VA, Bruera E. Comparison of symptom burden among patients referred to palliative care with hematologic malignancies versus those with solid tumors. J Pall Med. 2008;11(3):422–426. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elsayem A, Smith M, Parmley L, et al. Impact of a palliative care service on in-hospital mortality in a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(4):894–902. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braiteh F, El Osta B, Palmer JL, Reddy SK, Bruera E. Characteristics, findings, and outcomes of palliative care inpatient consultations at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(4):948–955. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delgado-Guay MO, Parsons HA, Li Z, Palmer LJ, Bruera E. Symptom distress, interventions, and outcomes of intensive care unit cancer patients referred to a palliative care consult team. Cancer. 2009;115(2):437–435. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhukovsky DS, Herzog CE, Kaur, Palmer JL, Bruera E. The impact of palliative care consultation on symptom assessment, communication needs, and palliative interventions in pediatric patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(4):343–349. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, et al. Predictors of access to palliative care services among patients who died at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(5):1146–1152. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osta BE, Palmer JL, Paraskevopoulos T, et al. Interval between first palliative care consult and death in patients diagnosed with advanced cancer at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(1):51–57. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hui D, Elsayem A, Palla S, De La Cruz M, et al. Discharge outcomes and survival of patients with advanced cancer admitted to an acute palliative care unit at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(1):49–57. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elsayem A, Mori M, Parsons HA, et al. Predictors of inpatient mortality in an acute palliative care unit at a comprehensive center. Support Care Cancer. 2009 Apr 7; doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0631-5. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elsayem A, Calderon BB, Camarines EM, et al. A month in an acute palliative care unit: clinical interventions and financial outcomes. Am J of Hosp Palliat Care. 2011;28(8):550–555. doi: 10.1177/1049909111404024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radwany S, Mason H, Clarke JS, et al. Optimizing the success of a palliative care consult service: how to average over 110 consults per month. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(5):873–883. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ritchie CS, Ceronsky L, Cote TR, et al. Palliative care programs: the challenges of growth. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(9):1065–1070. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.9768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norton SA, Powers BA, Schmitt MH, et al. Navigating tensions: integrating palliative care consultation services into an academic medical center setting. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(5):680–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Billings JA. Physician-nurse staffing on palliative care consultation services. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(6):819–820. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogle K. Staffing of palliative care consultation services in community Hospitals. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:509–510. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Babcock CW, Robinson LE. A novel approach to hospital palliative care: an expanded role for counselors. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(4):491–499. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruera E, Selmser P, Pereira J, Brenneis C. Bus rounds for palliative care education in the community. CMAJ. 1997;157(6):729–732. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zimmermann PG. Nursing management secrets. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, Inc.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Center to Advance Palliative Care. Tools for palliative care programs. Estimating consult volume. [Accessed July 14, 2011]; Available from www/capc.org/tools-for-palliative-care-programs. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holland WE. The adoption of palliative care. The engineering of organizational change. In: Breura E, Higginson IJ, Ripamonti C, Gunten CV, editors. Textbook of palliative medicine. London: Hodder Arnold; 2006. pp. 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, et al. Supportive versus palliative care: what’s in a name? Cancer. 2009;115:2013–2021. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dalal S, Palla S, Hui D, et al. Association between a name change from palliative to supportive care and the timing of patient referrals at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist. 2011;16:105–111. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Quality Forum. A national framework and preferred practices for palliative and hospice care quality. [Accessed August 29, 2011]; Available from http://www.qualityforum.org/Projects/n-r/Palliative_and_Hospice_Care_Framework/Palliative___Hospice_Care__Framework_and_Pract ices.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casarett D, Johnson M, Smith D, Richardson D. The optimal delivery of palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(7):649–655. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levy MH, Back A, Benedetti C, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Palliative care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:436–473. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferris FD, Bruera E, Cherny N, et al. Palliative cancer care a decade later: accomplishments, the need, next steps – from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3052–3058. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. Vol. 76. Pittsburgh, PA: National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, et al. Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(16):1783–1790. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.16.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zimmermann C, Riechelmann R, Krzysanowska M, Rodin G, Tannock I. Effectiveness of specialized palliative care. A systematic review. JAMA. 2008;299(14):1698–1708. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.14.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pantilat SZ, O’Riordan, Dibble S, Landefeld CS. Hospital-based palliative medicine consultation: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(22):2038–2039. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bruera E, Billings JA, Lupu D, Ritchie CS. AAHPM Position Paper: Requirements for the successful development of academic palliative care programs. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39(4):743–755. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]