Abstract

Iron is essential for most living organisms. Plants transcriptionally induce genes involved in iron acquisition under conditions of low iron availability, but the nature of the deficiency signal and its sensors are unknown. Here we report the identification of new iron regulators in rice, designated Oryza sativa Haemerythrin motif-containing Really Interesting New Gene (RING)- and Zinc-finger protein 1 (OsHRZ1) and OsHRZ2. OsHRZ1, OsHRZ2 and their Arabidopsis homologue BRUTUS bind iron and zinc, and possess ubiquitination activity. OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 are susceptible to degradation in roots irrespective of iron conditions. OsHRZ-knockdown plants exhibit substantial tolerance to iron deficiency, and accumulate more iron in their shoots and grains irrespective of soil iron conditions. The expression of iron deficiency-inducible genes involved in iron utilization is enhanced in OsHRZ-knockdown plants, mostly under iron-sufficient conditions. These results suggest that OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 are iron-binding sensors that negatively regulate iron acquisition under conditions of iron sufficiency.

Plants activate a gene transcription response under low iron conditions but how they sense insufficient iron levels is unclear. In this study, Kobayashi et al. identify two iron-binding proteins that possess ubiquitin ligase activity and are negative regulators of the iron deficiency response.

Plants activate a gene transcription response under low iron conditions but how they sense insufficient iron levels is unclear. In this study, Kobayashi et al. identify two iron-binding proteins that possess ubiquitin ligase activity and are negative regulators of the iron deficiency response.

Living organisms require various metal elements as cofactors for a wide variety of proteins. In humans, micronutrient malnutrition affects more than half of the world’s population, and iron (Fe) and zinc (Zn) deficiencies are among the most prevalent nutritional disorders worldwide1. Humans rely on plants as their primary source of both energy and minerals; thus, clarification of mineral homoeostasis in plants is of particular importance. Plants take up minerals from the soil, where Fe is abundant but exists predominantly as insoluble ferric hydroxides, especially in calcareous soils covering one-third of the world’s cultivated areas. Thus, Fe deficiency is a widespread agricultural problem that reduces plant growth, crop yield and crop quality2.

Under conditions of low Fe availability, higher plants utilize two major strategies for Fe acquisition3. Non-graminaceous plants utilize a reduction strategy, whereas graminaceous plants use a chelation strategy, which is mediated by the synthesis and secretion of natural Fe(III) chelators, the mugineic acid family phytosiderophores4. Genes that participate in both strategies are highly induced by low Fe availability, mainly at the transcriptional level5. Recently, a network of transcription factors that regulate the Fe-deficiency response have begun to be clarified; these appear to be only partially conserved among non-graminaceous and graminaceous plants5.

Despite substantial progress in understanding the response to Fe availability, signal substances and the sensors regulating this response have not been identified5,6. Recently, we identified direct Fe binding to a central regulator of the Fe-deficiency response in rice, iron deficiency-responsive element-binding factor 1 (IDEF1)7, suggesting that IDEF1 itself is an Fe sensor. Another candidate Fe-binding regulator in plants is BRUTUS (BTS) in Arabidopsis thaliana5,6, as this protein contains putative Fe-binding haemerythrin (also known as HHE) domains8. In invertebrates, this domain is known to bind to ferrous Fe and dioxygen, functioning as an oxygen-transporting protein9. This domain has also been suggested to be an oxygen sensor in bacteria10. Recently, this domain was also found in the human protein FBXL5 (refs 11, 12), which acts as an Fe sensor by degrading iron regulatory protein 2 under Fe-replete conditions through the ubiquitin–proteasome system. Plants do not contain this animal Fe-deficiency response system. In Arabidopsis, knockdown of the BTS gene results in enhanced tolerance to Fe deficiency8, even though the biochemical and physiological functions of the plant haemerythrin domain have yet to be characterized.

In our efforts to identify novel Fe regulators in rice, we previously identified several putative regulators whose expression was found by microarray analysis to be induced under conditions of Fe deficiency13. Among these, AK073385 and AK068704 correspond to the subsequently characterized basic helix–loop–helix transcription factors OsIRO2 and OsIRO3, respectively, both of which regulate the expression of various genes involved in Fe acquisition13,14,15,16. These results indicate the possible utility of analysing Fe deficiency-induced genes to identify unknown Fe regulators. In this study, we report the identification of new regulators in rice, designated OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2, whose expression is also induced under Fe deficiency. OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 bind Fe and Zn, and possess ubiquitination activity. OsHRZ-knockdown plants show Fe efficiency and accumulation, with enhanced expression of Fe utilization-related genes, indicating that OsHRZs are negative regulators of Fe-deficiency responses.

Results

OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 are Fe- and Zn-binding ubiquitin ligases

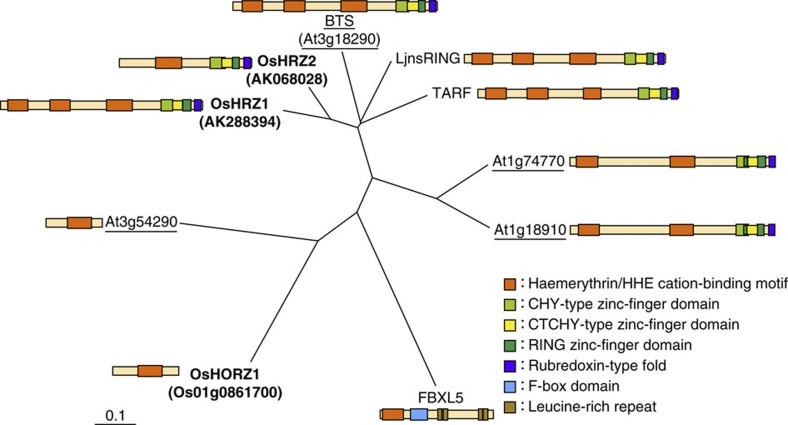

From our previously reported list of putative regulators whose expression was induced under conditions of Fe deficiency13, we identified a candidate Fe sensor, AK068028, which contains a putative Fe-binding haemerythrin domain (Fig. 1). Interestingly, AK068028 also contains a Really Interesting New Gene (RING) Zn-finger domain, present in many E3 ligases17,18, suggesting some functional similarity with human FBXL5, because the latter contains an F-box domain11,12 (Fig. 1), a part of the SCF complex of E3 ligases17,18. AK068028 also contains CHY- and CTCHY-type Zn-finger domains, which potentially interact with DNA, RNA, proteins or lipids19, and a rubredoxin-type fold, which is deduced to form an Fe–sulphur cluster for electron transport20. A database search revealed two more genes containing haemerythrin domains in rice and four genes in Arabidopsis (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. S1). Among the rice genes, AK288394 shares all domain structures with AK068028 and possesses two additional haemerythrin domains (Fig. 1). Thus, we designated AK288394 and AK068028 as OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2, respectively, for Oryza sativa Haemerythrin motif-containing RING- and Zn-finger proteins 1 and 2. Os01g0861700 contains a single haemerythrin domain but no other predicted domains; we therefore designated this protein as OsHORZ1, for Oryza sativa Haemerythrin motif-containing protein without RING- and Zn-finger 1 (Fig. 1). The closest homologue of OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 in Arabidopsis was found to be BTS (Fig. 1), which was previously identified as an Fe deficiency-induced gene expressed predominantly in the pericycle8. This gene was also identified as the embryonic lethal gene EMB2454 (ref. 21).

Figure 1. Phylogenetic tree and domain structures of HRZ and related haemerythrin domain-containing proteins.

Shown are all of the rice and Arabidopsis haemerythrin domain-containing proteins, with the names indicated by bold and underlining, respectively, and the other characterized haemerythrin domain-containing proteins in plants and humans. LjnsRING (accession number BAF38781.1) is a Lotus japonicus protein whose knockdown reduces symbiotic infection38. TARF (accession code BAJ16529.1) is a tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) protein whose silencing increases tobacco mosaic virus infection39. FBXL5 (accession code Q9UKA1) is a human (Homo sapiens) protein that senses Fe status and degrades iron regulatory protein 2 under Fe-replete conditions11,12.

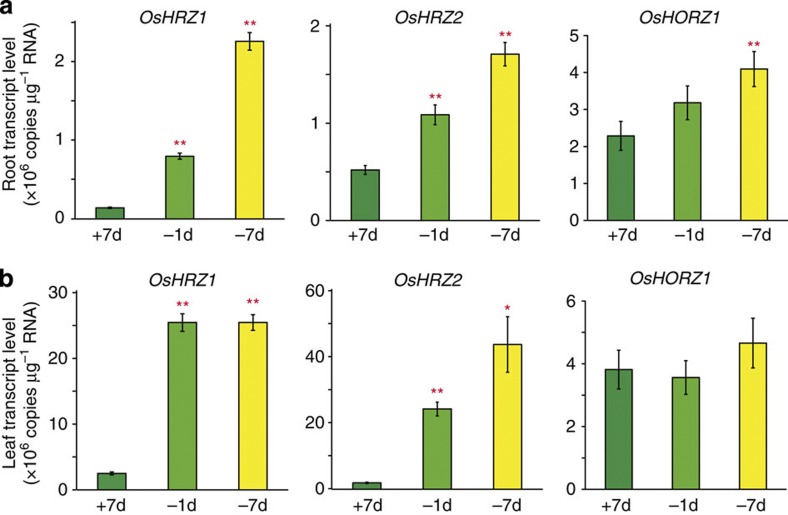

Expression analysis revealed that OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 transcripts were substantially induced under conditions of Fe deficiency in both roots and leaves, whereas OsHORZ1 expression was constitutive with slight or no induction in response to Fe deficiency (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S2). OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 expression was positively regulated by the transcription factor IDEF1, mainly at an early stage of Fe deficiency, but not by IDEF2 (Supplementary Fig. S2), another Fe-deficiency regulator in rice22. According to the RiceXPro microarray database23,24 ( http://ricexpro.dna.affrc.go.jp/index.html), OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 are widely expressed in various organs during the rice life span, and their expression in Fe-sufficient roots is highest in the stele.

Figure 2. Expression levels of HRZ and HORZ.

The transcript levels of OsHRZ1, OsHRZ2 and OsHORZ1 were quantified by RT–PCR in roots (a) and leaves (b) of hydroponically grown wild-type rice. +7d, Fe sufficiency for 7 days; −1d, Fe deficiency for 1 day; −7d, Fe deficiency for 7 days. Means±s.d. of three technical replicates derived from one biological replicate are shown. Asterisks indicate significant differences from the +7-day value (two-sample Student’s t-test; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; Supplementary Table S1).

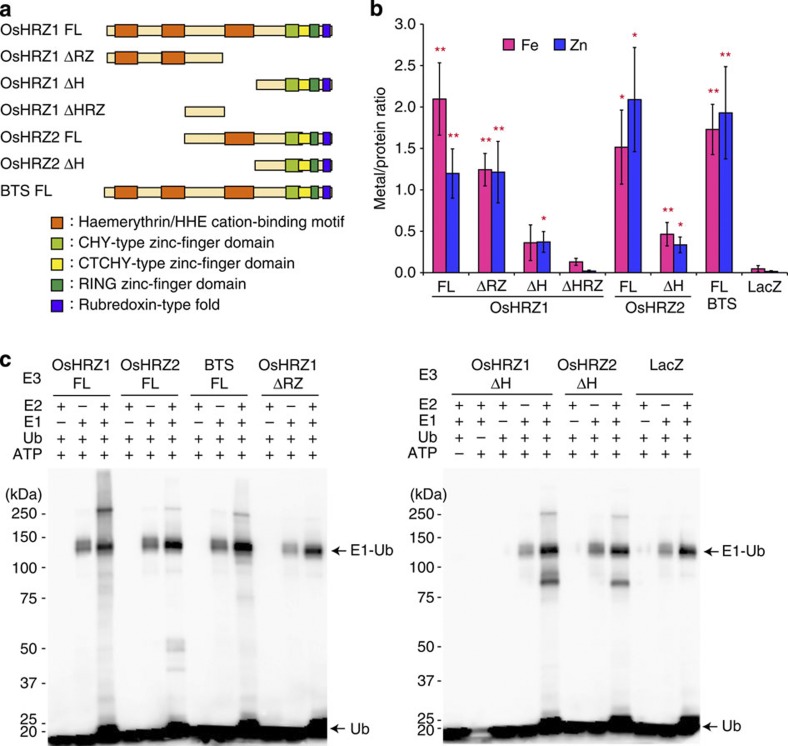

As there have been no previous reports regarding whether plant haemerythrin domains are capable of binding Fe, we examined this issue by measuring the metal concentrations of recombinant HRZ proteins fused to maltose-binding protein (MBP) expressed in Escherichia coli. Full-length OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 contained significant amounts of Fe and Zn (FL; Fig. 3a,b), and these binding capacities were markedly reduced by deletion of the haemerythrin domains (ΔH; Fig. 3a,b). Deletion of the RING and other Zn-finger domains or the rubredoxin-type fold did not markedly reduce the Fe or Zn content (ΔRZ; Fig. 3a,b), indicating that in HRZs, Fe and Zn are mainly bound to the haemerythrin domains. Arabidopsis BTS also contained Fe and Zn at similar levels as in OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 (Fig. 3b), suggesting the conservation of haemerythrin-type Fe- and Zn-binding proteins among plant species. The haemerythrin-containing HRZ proteins were a brownish-red colour (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Figure 3. Metal-binding analysis and ubiquitination assay of HRZ and BTS.

(a) Domain structures of the MBP fusions for the HRZ derivatives analysed. (b) Metal concentration analysis. MBP fusions of HRZ derivatives, or MBP-LacZ as a negative control, were expressed in E. coli, purified and subjected to metal concentration measurements by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry. Shown is the molar ratio of each metal per protein (means±s.e.m. of three to nine replicates derived from one to four biological replicates). Asterisks indicate significant differences from MBP-LacZ (two-sample Student’s t-test; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; Supplementary Table S1). (c) Ubiquitination assay. MBP fusions of HRZ derivatives, or MBP-LacZ as a negative control, were subjected to an in vitro ubiquitination assay with (+) or without (–) ATP, biotinylated ubiquitin (Ub) and human E1 and E2 (UbcH5a). Ubiquitinated proteins were detected by western blotting using a streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase conjugate detection system. The positions and sizes of the molecular mass markers are shown to the left of each blot. E1-ubiquitin (E1-Ub) conjugates and free ubiquitin (Ub) are indicated with arrows.

When E. coli cells were cultured with excess Fe, the amount of Zn bound to the haemerythrin regions of OsHRZ1 significantly decreased (Supplementary Fig. S3). Excess Zn in the E. coli cultures resulted in increased amounts of Zn bound to both haemerythrin and other regions of OsHRZ1 (Supplementary Fig. S3). These results suggest that the haemerythrin domains of HRZs bind competitively to Fe and Zn. HRZ and BTS did not contain detectable amounts of manganese (Mn) or copper (Cu) under any conditions examined.

We next examined whether plant haemerythrin-containing proteins possess E3 ligase activity with an in vitro ubiquitination assay using MBP-fused HRZ and BTS. OsHRZ1, OsHRZ2 and BTS were capable of mediating polyubiquitination in an E1-, E2- and ATP-dependent manner, as was evident by a high-molecular weight smear of ubiquitinated proteins (Fig. 3c). Deletion of the haemerythrin domains did not affect this polyubiquitination activity (ΔH; Fig. 3a,c), whereas this activity was abolished by deletion of the C-terminal domains containing the RING and other Zn-finger domains (ΔRZ; Fig. 3a,c). Thus, OsHRZ1, OsHRZ2 and BTS function as E3 ligases, and this activity does not require haemerythrin domains. Detection of MBP-HRZ fusions by anti-MBP antibody also resulted in appearance of a high-molecular weight smear of HRZ proteins in an E1-, E2- and ATP-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. S3), suggesting that OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 are self-ubiquitinated.

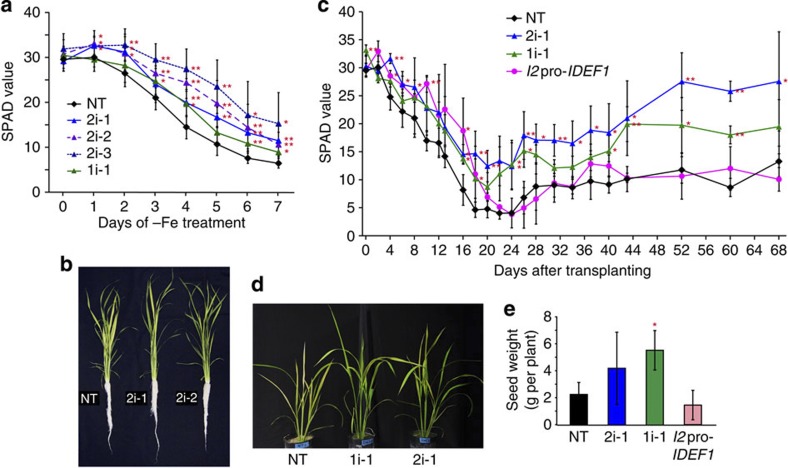

HRZ knockdown in rice confers Fe-deficiency tolerance

We generated HRZ-knockdown rice lines by RNA interference (RNAi) using partial sequences of OsHRZ1 or OsHRZ2 (HRZ1i and HRZ2i lines, respectively). The HRZ2i lines showed reduced OsHRZ2 expression in Fe-sufficient and -deficient roots and leaves compared with the non-transformants (NT), and also moderate reduction in OsHRZ1 and OsHORZ1 expression in Fe-sufficient leaves (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S4). These lines also tended to show reduced expression of OsHRZ1 in Fe-deficient roots (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S4). HRZ1i line 1 showed only a tendency of slight reduction in the expression of OsHRZ1 in roots and OsHORZ1 in leaves, but none in OsHRZ2 expression (Supplementary Fig. S4). These knockdown lines grew healthily with no visible phenotype under normal growth conditions. To analyse the Fe nutrition in these lines, Fe-deficiency treatment was imposed hydroponically. A gradual decrease in leaf chlorophyll levels occurred (Fig. 4a), an indicator of Fe deficiency in plants2. The knockdown lines, especially HRZ2i, retained significantly higher levels of leaf chlorophyll than NT under conditions of Fe deficiency (Fig. 4a,b).

Table 1. Microarray analysis of the HRZ-knockdown roots.

| RAP Locus | Gene | +Fe 7d Root | −Fe 1d Root | −Fe 7d Root | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|

2i-1/NT |

2i-2/NT |

2i-3/NT |

2i-1/NT |

2i-2/NT |

2i-3/NT |

2i-1/NT |

2i-2/NT |

2i-3/NT |

| Haemerythrin domain-containing genes | ||||||||||

| Os01g0689300 | OsHRZ1 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.72 |

| Os05g0551000 | OsHRZ2 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.55 | 0.68 | 0.72 | 0.56 | 0.51 | 0.65 | 0.42 |

| Os01g0861700 | OsHORZ1 | 0.83 | 0.98 | 0.85 | 1.15 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 1.05 |

| Transcriptional regulation of Fe-deficiency responses | ||||||||||

| Os08g0101000 | IDEF1 | 0.93 | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.81 | 1.15 | 1.05 | 0.94 | 1.05 | 1.17 |

| Os05g0426200 | IDEF2 | 1.10 | 1.04 | 1.06 | 1.35 | 0.90 | 1.09 | 1.15 | 1.20 | 1.01 |

| Os01g0952800 | OsIRO2 | 4.52 | 2.42 | 6.45 | 2.58 | 1.22 | 2.65 | 0.74 | 0.59 | 1.20 |

| Os03g0379300 | OsIRO3 | 3.03 | 1.74 | 4.88 | 1.32 | 1.38 | 2.21 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 1.52 |

| Biosynthesis of mugineic acid family phytosiderophores | ||||||||||

| Os03g0307300 | OsNAS1 | 27.49 | 55.61 | 70.76 | 16.03 | 3.36 | 5.99 | 1.03 | 0.85 | 0.98 |

| Os03g0307200 | OsNAS2 | 27.36 | 50.97 | 63.34 | 16.99 | 3.93 | 7.26 | 1.04 | 0.96 | 1.16 |

| Os07g0689600 | OsNAS3 | 3.29 | 3.63 | 4.54 | 1.22 | 4.10 | 3.02 | 3.91 | 7.00 | 8.39 |

| Os02g0306400 | OsNAAT1 | 4.59 | 7.32 | 9.33 | 2.59 | 1.64 | 2.80 | 1.08 | 0.71 | 1.16 |

| Os03g0237100 | OsDMAS1 | 8.10 | 8.92 | 8.31 | 1.88 | 1.02 | 1.37 | 1.11 | 0.64 | 1.14 |

| Fe uptake and/or translocation | ||||||||||

| Os11g0134900 | TOM1 | 4.77 | 11.84 | 22.56 | 1.98 | 3.56 | 4.48 | 0.99 | 0.82 | 1.26 |

| Os02g0650300 | OsYSL15 | 10.53 | 15.49 | 18.58 | 39.10 | 4.21 | 4.66 | 0.90 | 1.06 | 1.11 |

| Os11g0151500 | ENA1 | 6.40 | 7.13 | 5.88 | 4.25 | 1.33 | 2.04 | 1.21 | 0.88 | 1.58 |

| Os02g0649900 | OsYSL2 | 51.42 | 0.96 | 74.36 | 14.85 | 1.09 | 60.00 | 160.29 | 1.26 | 194.37 |

| Os03g0667500 | OsIRT1 | 1.82 | 3.28 | 3.32 | 2.39 | 1.41 | 1.61 | 0.72 | 0.81 | 1.13 |

| Os03g0667300 | OsIRT2 | 4.71 | 6.10 | 7.29 | 1.19 | 1.84 | 1.93 | 0.74 | 0.60 | 1.04 |

| Os07g0258400 | OsNRAMP1 | 5.51 | 3.72 | 6.63 | 1.79 | 1.60 | 2.19 | 0.90 | 0.75 | 1.21 |

Listed are haemerythrin domain-containing genes, transcriptional regulators of Fe-deficiency responses and Fe deficiency-inducible genes involved in Fe uptake and utilization5. With the exception of OsHORZ1, IDEF1 and IDEF2, all of the indicated genes are transcriptionally induced under conditions of Fe deficiency (Fig. 2)5. The non-transformants (NT) and HRZ2i lines 1, 2 and 3 (2i-1, 2i-2 and 2i-3, respectively) were treated under conditions of Fe sufficiency for 7 days (+Fe 7d) or under conditions of Fe deficiency for 1 day (–Fe 1d) or 7 days (–Fe 7d) in hydroponic culture. Shown are the expression ratios calculated as (signal values of the HRZ2i line)/(signal values of the corresponding NT). The signal values of those genes with multiple spots on the array for a single RAP locus are shown as geometric averages. Ratios with Agilent’s P-value<0.05 (two-sample Student’s t-test) are indicated in bold. Ratios with low expression (signal value <20) are indicated in italics. For OsHRZ2 expression, only the ratio obtained by the probe that did not detect the transgene of the HRZ2i construct is shown.

Figure 4. Fe-deficiency tolerance of the HRZ-knockdown plants.

(a) Fe-deficiency tolerance in hydroponic culture. Relative chlorophyll contents (SPAD values) of the newest leaves were measured after the onset of Fe-deficiency treatment. (b) Representative plants on day 7 of Fe-deficiency treatment. (c) Fe-deficiency tolerance in calcareous soil. The SPAD value of the newest leaves was measured after transplanting into pots containing calcareous soil. (d) Representative plants on day 28 in calcareous soil. (e) Yields in the calcareous pot experiment. NT, non-transformant; 2i-1, 2i-2 and 2i-3, HRZ2i lines 1, 2 and 3, respectively; 1i-1, HRZ1i line 1; I2pro-IDEF1, IDEF1 induction line 13 (refs 7, 25, 26). For (a), (c) and (e), means±s.d. of six to nine biological replicates for (a) and three to four biological replicates for (c) and (e) are shown. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with NT (two-sample Student’s t-test; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; Supplementary Table S1).

To further characterize the growth features of these lines in problem soils with low Fe availability, we performed a long-term experiment in calcareous soil. For comparison, we also tested a previously generated line by inducing expression of the transcription factor IDEF1 (I2pro-IDEF1), which confers Fe-deficiency tolerance7,25,26. Within 20 days after transplantation, the chlorophyll content had gradually decreased in all lines, but this decrease was less severe in the HRZ-knockdown lines than in NT (Fig. 4c). Furthermore, the chlorophyll levels gradually recovered after day 22 in these lines, especially the HRZ2i line (Fig. 4c,d). The I2pro-IDEF1 line also showed a higher chlorophyll content within 20 days, but this line failed to retain any tolerance after day 22 (Fig. 4c). At harvest, the HRZ-knockdown lines tended to show a higher grain yield than NT, but the I2pro-IDEF1 line did not (Fig. 4e).

HRZ-knockdown rice accumulates Fe in shoots and grains

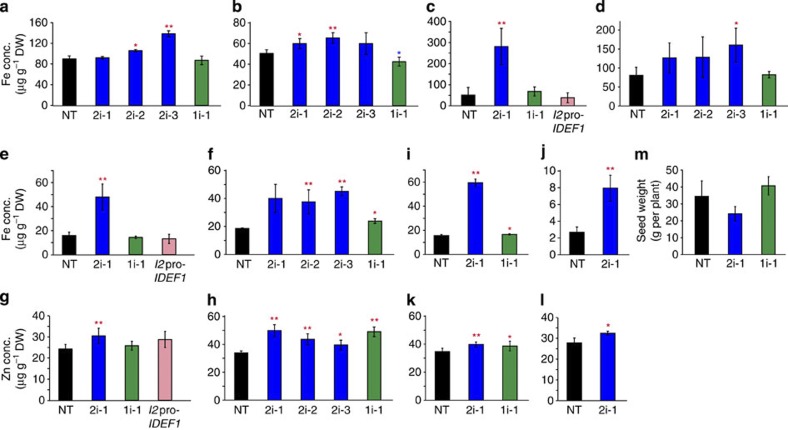

To investigate the mechanisms underlying the Fe-deficiency tolerance of the HRZ-knockdown lines, we measured the metal concentrations in these lines. The HRZ2i lines, but not the HRZ1i line, accumulated higher concentrations of Fe in their leaves and straws than NT, under both Fe-sufficient and -deficient conditions (Fig. 5a–d). There were no marked differences in Zn, Mn and Cu concentrations (Supplementary Fig. S5). Notably, brown seeds of the HRZ2i lines showed much higher concentrations of Fe and moderately higher concentrations of Zn than NT following cultivation in both calcareous and normal soils (Fig. 5e–h). The HRZ1i line showed moderately higher levels of Fe and Zn in brown seeds from normal soil, but not in those from calcareous soil (Fig. 5e–h).

Figure 5. Fe and Zn accumulation in shoots and seeds of the HRZ-knockdown plants.

(a and b) Fe concentration in leaves subjected to Fe-sufficient (a) or Fe-deficient (b) hydroponic treatment for 7 days. (c and d) Fe concentrations in straws at harvest from pot culture in calcareous (c) or normal (d) soil. (e and f) Fe concentrations in brown seeds from pot culture in calcareous (e) or normal (f) soil. (g and h) Zn concentrations in brown seeds from pot culture in calcareous (g) or normal (h) soil. (i and j) Fe concentrations in brown (i) or polished (j) seeds from field cultivation in normal soil. (k and l) Zn concentrations in brown (k) or polished (l) seeds from field cultivation in normal soil. The Fe and Zn concentrations are shown as means±s.d. of μg g−1 dry weight (DW) of three to eight replicates derived from three to four biological replicates. (m) Yields from field cultivation in normal soil, shown as seed weight per plant (means±s.d. of three biological replicates). NT, non-transformant; 2i-1, 2i-2 and 2i-3, HRZ2i lines 1, 2 and 3, respectively; 1i-1, HRZ1i line 1; I2pro-IDEF1, IDEF1 induction line 13. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with NT (two-sample Student’s t-test; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; Supplementary Table S1).

With the aim of future applications to Fe and Zn fortification, these lines were then cultured until harvest in a field of normal soil. The HRZ2i line concentrated about 3.8- and 2.9-fold more Fe in its brown and polished seeds, respectively, compared with the NT (Fig. 5i,j). Moderate increases were also observed for Zn in the brown and polished seeds of the HRZ2i line, as well as Fe and Zn in the brown seeds of the HRZ1i line (Fig. 5i–l). The HRZ2i line also tended to accumulate moderately more Mn in its brown seeds in both pot and field experiments (Supplementary Fig. S5). These lines showed yields similar to those of NT (Fig. 5m).

Fe utilization genes are upregulated in HRZ-knockdown rice

We performed a 44 K microarray analysis to investigate the gene expression profiles of the HRZ2i lines grown hydroponically. In Fe-sufficient roots, the HRZ2i lines exhibited strikingly enhanced expression of various Fe uptake- and utilization-related genes, whose expression is normally induced by Fe deficiency but repressed at low levels under conditions of Fe sufficiency in NT (Table 1). This tendency was somewhat weakened or reversed with the progression of Fe-deficiency treatment (Table 1), which may have been partially due to the stronger induction of these genes in NT because of the more severe Fe deficiency. Nevertheless, the expression levels of some genes, including OsNAS3 and OsYSL2, remained much higher in the knockdown lines even under prolonged conditions of Fe deficiency. Expression of constitutive regulators IDEF1 and IDEF2 was not affected by HRZ knockdown (Table 1). These microarray results were validated by quantitative RT–PCR analysis for several representative genes (Supplementary Figs S4 and S6). The HRZ1i line 1 also showed a similar, but much weaker, expression enhancement (Supplementary Fig. S6). These results indicate that OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 negatively regulate the Fe-deficiency response, especially under conditions of Fe sufficiency.

Quantitative RT–PCR was also performed to analyse gene expression in leaves (Supplementary Fig. S6). Enhanced expression of some Fe utilization-related genes in the HRZ-knockdown lines was also observed in leaves, but this enhancement was less pronounced than in roots.

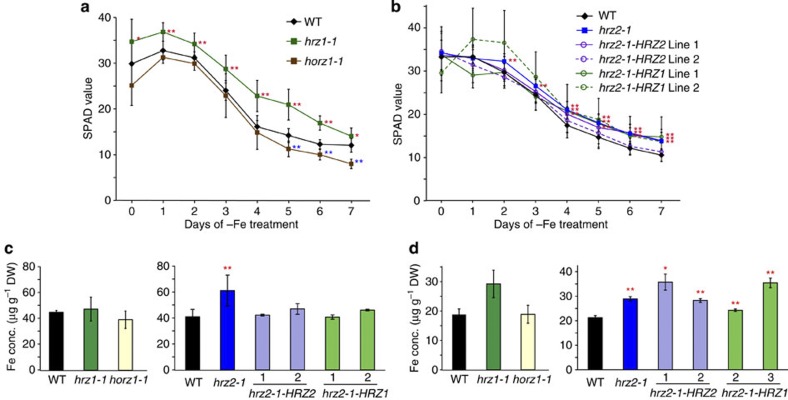

OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 have similar but not identical functions

To further characterize the specific functions of the three haemerythrin motif-containing genes in rice, we obtained transfer-DNA (T-DNA) insertion lines of OsHRZ1 (hrz1-1) and OsHORZ1 (horz1-1) as well as a Tos17-insertion line of OsHRZ2 (hrz2-1) (Supplementary Fig. S7). The hrz2-1 and horz1-1 lines grew well, but the hrz1-1 line showed severely repressed growth in the late-adult and maturing stages in normal soil, resulting in extremely low grain yield compared with wild-type (WT) plants (Supplementary Fig. S7). The hrz1-1 and hrz2-1 lines exhibited specific and substantial repression of OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2, respectively, with little change in the expression of other haemerythrin-containing genes (Supplementary Fig. S7). The horz1-1 line showed strong repression of OsHORZ1, and moderate repression of OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 under Fe deficiency (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Fe-deficiency treatment in hydroponic culture revealed that the hrz1-1 and hrz2-1 lines were moderately more tolerant to Fe deficiency than WT (Fig. 6a,b). In contrast, the horz1-1 line showed hypersensitivity to Fe deficiency from day 5 of treatment (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6. Fe-deficiency tolerance and Fe accumulation in the HRZ insertion and complementation lines.

(a and b) Fe-deficiency tolerance in hydroponic culture. The SPAD value of the newest leaves was measured after the onset of Fe-deficiency treatment. Means±s.d. of four to 15 biological replicates. (c) Fe concentrations in leaves subjected to Fe-deficient hydroponic treatment for 7 days. (d) Fe concentrations in brown seeds from pot culture in normal soil. Fe concentrations are shown as means±s.d. of μg g−1 DW of two to eight replicates derived from two to four biological replicates. WT, wild-type cultivar DongJing for hrz1-1 and horz1-1, and cultivar Nipponbare for hrz2-1 and the complementation lines. The line numbers of the hrz2-1-HRZ2 and hrz2-1-HRZ1 complementation lines are shown as numerals. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with WT (two-sample Student’s t-test; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; Supplementary Table S1).

Metal concentration measurements in leaves revealed that the hrz2-1 line contained higher Fe concentrations under Fe deficiency, but the hrz1-1 and horz1-1 lines did not (Fig. 6c). Under Fe-sufficient conditions, the hrz1-1 and hrz2-1 lines contained similar levels of Fe as WT, whereas the horz1-1 line showed slightly decreased Fe and Zn concentrations (Supplementary Fig. S8). The hrz2-1 line also showed slightly decreased Zn and Cu concentrations in Fe-sufficient leaves (Supplementary Fig. S8). In brown seeds from pots containing normal soil, the hrz1-1 and hrz2-1 lines showed 1.4- to 1.5-fold increases in the Fe concentration, but the horz1-1 line contained similar Fe concentrations as WT (Fig. 6d). There was no marked difference in Zn, Mn or Cu concentration in seeds, except for some increases in Zn concentration in the hrz1-1 and horz1-1 lines (Supplementary Fig. S8).

The hrz1-1 and hrz2-1 lines also showed enhanced expression of Fe utilization-related genes in roots, and this effect was especially pronounced under Fe-sufficient conditions in the hrz1-1 line (Supplementary Fig. S9). In contrast, the horz1-1 line showed decreased expression of these Fe utilization-related genes under conditions of both Fe sufficiency and deficiency (Supplementary Fig. S9). These results indicate that both OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 negatively regulate Fe efficiency and accumulation, whereas OsHORZ1 may have the opposite effect.

To gain further insight into the individual functions of OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2, we carried out a complementation test by transforming the hrz2-1 line with either OsHRZ1 or OsHRZ2 fused to the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene under the control of the barley Fe deficiency-inducible IDS2 promoter (hrz2-1-HRZ1 and hrz2-1-HRZ2 lines). These complementation lines expressed the GFP-OsHRZ1 or GFP-OsHRZ2 transgene moderately in Fe-sufficient roots and strongly in Fe-deficient roots (Supplementary Figs S7 and S9), in accordance with the activity of the IDS2 promoter27. In hydroponics, these lines partially lost the Fe-deficiency tolerance of the hrz2-1 line (Fig. 6b); hrz2-1-HRZ2 line 2 and hrz2-1-HRZ1 line 1 did not show any significant differences in leaf chlorophyll level compared with WT, and hrz2-1-HRZ2 line 1 and hrz2-1-HRZ1 line 2 showed significant tolerance compared with NT only during days 4–7 of treatment, in contrast to the hrz2-1 background, which showed significant tolerance during days 2–7. These complementation lines also negated the Fe accumulation of the hrz2-1 line in leaves (Fig. 6c), but not in brown seeds (Fig. 6d). The enhanced gene expression in the hrz2-1 line was reduced in the complementation lines for OsNAS2, but tended to be stronger for OsIRO2 and OsYSL2 (Supplementary Fig. S9). Thus, the OsHRZ2 knockdown phenotype was complemented partly, but not entirely, by either OsHRZ1 or OsHRZ2 expression.

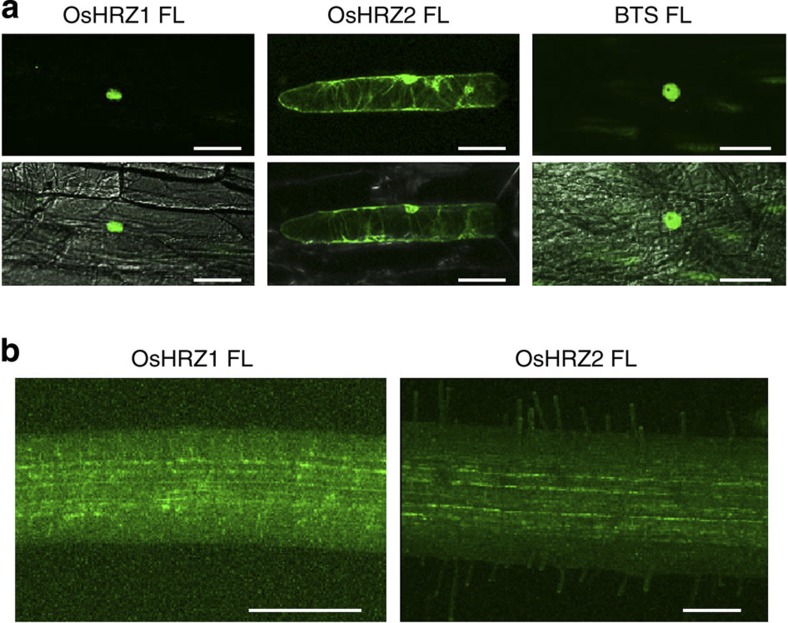

OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 are susceptible to degradation in roots

Subcellular localization and stability of HRZs was investigated using GFP fusions. When transiently expressed in onion bulb epidermal cells, OsHRZ1 and BTS mostly localized to the nucleus, while OsHRZ2 localized to the nucleus and cytosol (Fig. 7a). However, GFP fluorescence was barely detectable in stable rice transformants of the GFP-OsHRZ1 or GFP-OsHRZ2 in the hrz2-1 background (Fig. 7b), even though these lines highly expressed GFP transcripts in accordance with HRZ transgene expression (Supplementary Figs S7 and S9). We could detect no GFP signal in Fe-sufficient roots, and only a faint signal was occasionally observed at the cell periphery in restricted parts of the Fe-deficient roots (Fig. 7b). These results suggest that OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 are susceptible to protein degradation in rice roots.

Figure 7. HRZ-GFP observation in transient and stable transformants.

(a) Subcellular localization in onion cells. Full-length (FL) OsHRZ1, OsHRZ2 or BTS fused to GFP was transiently expressed in onion bulb epidermal cells and observed by confocal microscopy. Upper panels, GFP fluorescence images; lower panels, overlay with the transmission images. (b) Cellular and subcellular localization in Fe-deficient rice roots. The hrz2-1-HRZ1 and hrz2-1-HRZ2 complementation lines, fused to GFP driven by the barley IDS2 promoter, were subjected to Fe-deficient hydroponic treatment for 3 days, and their roots were observed by confocal microscopy. Scale bars, 100 μm.

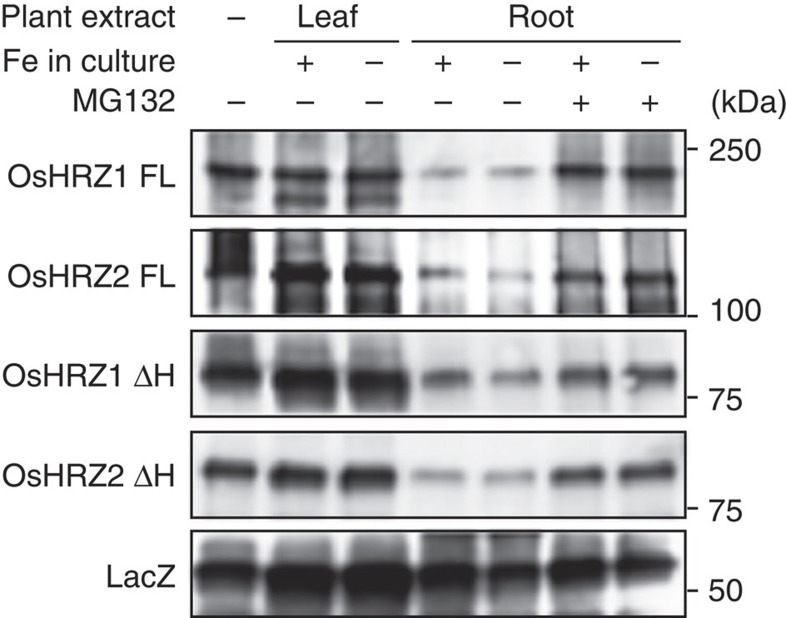

To further analyse the stability of the HRZ proteins, we performed a cell-free degradation assay, which can recapitulate the 26S proteasome-dependent pathway in vitro28, using recombinant MBP-HRZ proteins and rice protein extracts. Root extracts rapidly degraded both OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2, but leaf extracts had much less effect, even with 20-times more total protein than the root extracts (Fig. 8, Supplementary Fig. S10). Addition of MG132, a specific inhibitor of the 26S proteasome, effectively inhibited degradation by the root extracts. The degradation activity was not greatly affected by Fe nutritional conditions in the plant culture or by deletion of the haemerythrin domains (ΔH; Fig. 8, Supplementary Fig. S10). MBP-LacZ protein was much less susceptible to degradation. These results suggest that OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 are specifically degraded in rice roots via the 26S proteasome pathway irrespective of Fe status.

Figure 8. Cell-free degradation assay of HRZ.

MBP fusions of HRZ derivatives, or MBP-LacZ as a negative control, were expressed in E. coli and purified; 0.25 μg of each was incubated for 20 min at 28 °C with or without (–) protein extracts from leaves (20 μg total protein) or roots (1 μg total protein) of wild-type rice cultured hydroponically under Fe sufficiency (+) or deficiency (−) for 7 days. The reaction was carried out with (+) or without (−) 160 μM of MG132. MBP-HRZ proteins were detected by western blotting using anti-MBP antibody. The positions and sizes of the molecular mass markers are shown to the right of the blots. The full gel images are shown in Supplementary Fig. S10.

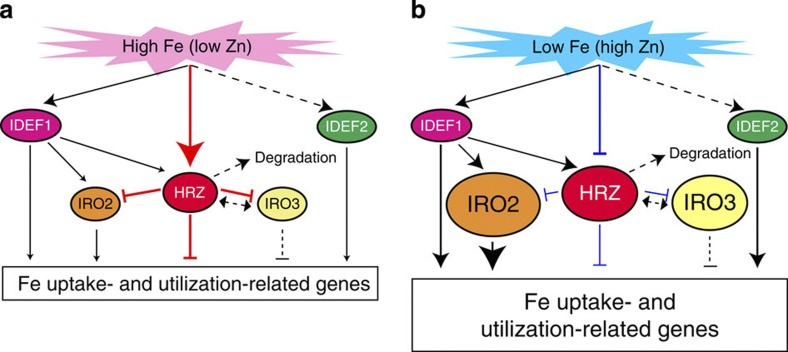

Taken together, our results indicate that OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 are negative regulators of Fe-deficiency response and Fe accumulation. Expression of HRZs is transcriptionally induced under Fe deficiency, and HRZ proteins are susceptible to degradation. A hypothetical model for the signal transmission and regulation of Fe deficiency-inducible genes by HRZs is shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 9. Hypothetical model of the signal transmission and regulation of Fe deficiency-inducible genes.

(a) Fe-sufficient conditions. (b) Fe-deficient conditions. In rice, the transcription factors IDEF1, IDEF2, OsIRO2 and OsIRO3 are known regulators of various Fe deficiency-inducible genes involved in Fe uptake and utilization5. IDEF1 binds to Fe and other metals (mainly Zn), and is thus proposed to be an Fe sensor that detects the cellular concentration ratio between Fe and other metals7. In the present study, we demonstrated that OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 also bind to Fe and Zn, presumably also serving as Fe sensors. HRZ proteins are likely to be rapidly degraded in roots irrespective of Fe status. HRZs negatively regulate the expression of various Fe deficiency-inducible genes involved in Fe uptake and utilization, mainly under conditions of Fe sufficiency (a). HRZs might function as modulators of the possible overexpression of Fe deficiency-inducible genes. On the other hand, HRZs may reduce or change their repression activity under Fe-deficient conditions as a consequence of the changes in Fe and Zn binding to haemerythrin domains (b). HRZs may indirectly interact with OsIRO3 because Arabidopsis BTS indirectly interacts with the basic helix–loop–helix transcription factor POPEYE8, which is a homologue of OsIRO3 (ref. 16), through the other basic helix–loop–helix transcription factors ILR3 and AtbHLH115. With the exception of IDEF1 and IDEF2, all of the indicated genes are transcriptionally induced under conditions of Fe deficiency (Fig. 2)5. The expression of HRZ genes is also positively regulated by IDEF1 (Supplementary Fig. S2). Thus, HRZs appear to form a negative feedback loop of Fe-deficiency signalling transmitted via IDEF1. However, gene expression analysis in HRZ-knockdown lines indicated that HRZs regulate both IDEF1-dependent and -independent genes (Table 1)26. Therefore, HRZs may also be involved in Fe sensing bypassing the IDEF1 pathway. The thickness of the lines and size of the arrowheads indicate the relative strength of the regulation. Putative or unverified pathways are indicated by broken lines.

Discussion

Here, we identified two rice Fe-binding regulators, OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2. Unexpectedly, the haemerythrin domains of these HRZ proteins bound large amounts of Zn in addition to Fe (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. S3). Some haemerythrin-like proteins have been reported to be capable of binding Zn, Mn, cobalt or cadmium in place of Fe29,30,31. However, Fe is generally thought to be the favoured metal for known haemerythrin proteins, as these metal substitutions were mostly derived from artificial treatments during structural analysis or exposure of an organism to the metal prior to extraction. Thus, comparable Fe and Zn binding by plant haemerythrin-containing proteins might reflect their unique roles in plants. Plants might sense Fe availability based on the ratios of free Fe to other metals such as Zn. This notion has also been proposed from the properties of IDEF1, which also binds to Fe and other divalent metals, including Zn, Cu and nickel7. In addition to metal binding, most known haemerythrin proteins are also implicated in oxygen binding9,10,11,12. In graminaceous plants, the responses to Fe deficiency and hypoxia are intimately related: Fe deficiency causes physiological hypoxia32, whereas submergence and hypoxia induce enzymes involved in phytosiderophore and ethylene biosynthesis33,34,35. Ethylene positively regulates the Fe-deficiency response36. Thus, plant haemerythrin-containing regulators might also bind to oxygen and link the responses to Fe deficiency and hypoxia.

We also demonstrated that HRZ proteins possess ubiquitination activity in vitro (Fig. 3c), suggesting a possible role in ubiquitin-mediated degradation or modification of proteins involved in Fe homoeostasis. The domain structure of HRZ proteins is reminiscent of receptors of plant hormones such as auxin and jasmonic acid, which also contain ligand-binding domains and constituents of E3 ligases17,18. It is conceivable that plants have developed various molecular sensors by combining E3 ligase constituents, as has also been suggested for human FBXL5 (ref. 37). However, differences are evident in expressional regulation of haemerythrin-containing proteins between plant and animal systems; FBXL5 maintains a constitutive transcript level irrespective of Fe status12, and FBXL5 degradation is enhanced under conditions of Fe deficiency and hypoxia11,12. In contrast, OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 are transcriptionally induced under Fe deficiency (Fig. 2), but the proteins are suggested both by in vivo and in vitro studies to be rapidly degraded in roots under both Fe sufficiency and deficiency (Figs 7b and 8). Further investigation will be needed to clarify how the HRZ protein level is regulated in plant organs.

Arabidopsis BTS indirectly interacts with the transcription factor POPEYE, disruption mutants of which are hypersensitive to Fe deficiency8. In contrast, knockdown mutants of BTS exhibit Fe-deficiency tolerance8. However, no previous reports have characterized BTS mutants with respect to Fe content and gene regulation. We identified various interesting and favourable traits in HRZ-knockdown rice plants with repressed expression of OsHRZ1 or OsHRZ2 or both (Figs 4, 5, 6, Table 1, Supplementary Figs S4–S9). These traits include tolerance to low Fe availability and accumulation of Fe in seeds and shoots. Derepression of the expression of various Fe uptake- and utilization-related genes was evident in these plants, which could be responsible for these traits. An analysis of insertion and complementation lines showed that both OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2 are involved in the above-mentioned phenotypes in similar but not identical fashion. For example, the hrz1-1 line set very few seeds, whereas the hrz2-1 line was fully fertile (Supplementary Fig. S7). It has been reported that a knockout embryo of Arabidopsis BTS is lethal8,21, suggesting some functional similarity between OsHRZ1 and BTS in embryogenesis. The expression of Fe utilization-related genes was generally more affected in the hrz1-1 line than in the hrz2-1 line, and the effect of complementation on the expression of these genes appeared to be slightly different between the OsHRZ1- and OsHRZ2-introduced lines (Supplementary Fig. S9). The HRZ-introduced lines did not completely complement the phenotypes of the hrz2-1 line (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. S9). The IDS2 promoter used for complementation might not completely fit the expression for the proper functioning of HRZs. Also, we cannot exclude the possibility that the hrz2-1 line might express carboxy-terminal-truncated proteins, because the Tos17-insertion was situated in the rubredoxin-type fold (Supplementary Fig. S7), leading to a possible influence on the phenotype. Interestingly, the horz1-1 line exhibited an Fe-inefficient phenotype and reduced expression of Fe utilization-related genes (Fig. 6a, Supplementary Fig. S9). The structure of OsHORZ1, with a haemerythrin domain but without other functional domains (Fig. 1), might antagonize HRZ function.

A calcareous soil test revealed that the HRZ-knockdown lines maintained tolerance until harvest, whereas the IDEF1 induction line showed tolerance only during the early stages (Fig. 4c–e). IDEF1 induction under prolonged Fe deficiency has a negative effect on some Fe uptake-related genes26, which may account for the failure of this line to show sustainable tolerance. Notably, seeds of the HRZ2i lines accumulated much more Fe than NT seeds without an apparent yield penalty, irrespective of the growth conditions (Figs 4e and 5e–m). These properties would be especially favourable with respect to Fe availability in culturing Fe-fortified crops in fluctuating environments, including calcareous and semi-arid regions. Knockdown of a Lotus japonicus HRZ homologue, LjnsRING, reduces symbiotic infection38, whereas silencing of another HRZ homologue in tobacco, TARF, enhances tobacco mosaic virus infection39. For future application of HRZ-knockdown plants, precise investigation of the resistance to various infections is needed.

Fe and Zn fortification in transgenic rice grains has been accomplished by various approaches5, including endosperm-specific expression of the Fe storage protein ferritin40, overexpression of nicotianamine synthase (NAS) genes41,42, introduction of mugineic acid synthase (IDS3) gene43,44 and introduction of the Fe(II)-nicotianamine transporter OsYSL2 driven by a sucrose transporter promoter45. Combined introduction of these genes is more effective46,47. In our HRZ-knockdown lines, OsNAS1, OsNAS2, OsNAS3 and OsYSL2 expression showed marked enhancement in roots and leaves (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S6). In particular, the hyper-induction of OsYSL2 expression was dominant and sustained even under Fe deficiency, showing a distinct pattern of expression compared with other known Fe homoeostasis-related genes (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S6). These expression patterns of OsNAS1-3 and OsYSL2 may be advantageous both for sustainable Fe efficiency and consequent Fe accumulation in grains, even in calcareous soils. However, the HRZ-knockdown lines showed less tolerance in calcareous soils compared with previously reported highly tolerant lines, such as those with induction of ferric-chelate reductase48 or overexpression of the transcription factor OsIRO2 (ref. 15). Further introduction of HRZ-independent mechanisms, including ferritin and ferric-chelate reductase, into HRZ-knockdown lines may serve as a powerful means of developing more Fe-efficient and -fortified plants for improved food and biomass production.

Our results indicate that HRZs are potent negative regulators of Fe-deficiency response and Fe accumulation, possibly situating at the core of signal transmission and regulation of Fe deficiency-inducible genes, because HRZs also regulate the expression of other Fe deficiency-inducible regulators OsIRO2 and OsIRO3 (Fig. 9). HRZs may repress Fe utilization-related genes via protein degradation or modification, transcriptional regulation, interactions with other regulators and/or protein stability or localization of HRZs themselves. In addition, HRZs might sense Fe status by binding Fe and Zn, and reduce or change their repression activity under Fe-deficient conditions. Future studies of HRZ function will elucidate plant Fe-sensing mechanisms and their physiological relevance.

Methods

Primers

The primers used are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Bioinformatics

A domain search was carried out using the InterPro Beta Programme provided by the European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI; http://wwwdev.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/)49. Phylogenetic analysis and sequence alignments were carried out using ClustalW provided by the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ; http://clustalw.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/index.php?lang=ja)50.

Plant materials and growth conditions

For the expression analysis of WT rice plants, Oryza sativa L. cultivar Nipponbare was germinated and cultured hydroponically as described previously7,51. IDEF1 dependence was analysed as described7,26. T-DNA insertion lines of hrz1-1 (3A-06066) and horz1-1 (1B-18902) (background cultivar: DongJing) were obtained from the Rice T-DNA Insertion Sequence Database52 (POSTECH; Pohang University of Science and Technology, Pohang, Korea). The Tos17-insertion line of hrz2-1 (ND6059; background cultivar: Nipponbare) was obtained from the Rice Genome Resource Center53 ( http://tos.nias.affrc.go.jp/). Homozygous progeny of hrz2-1 were used for further analysis. HRZ-knockdown and complementation plants were obtained as described below.

Hydroponic culture of the HRZ-knockdown, insertion and complementation lines was carried out as reported previously7 after germination on Murashige and Skoog medium with or without hygromycin B (50 mg l−1) for transformants and other rice lines, respectively. Pot cultivation on normal soil was carried out by transplanting each germinated seedling into a 1-l pot filled with a 1:1 mixture of Bonsol (Sumitomo Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) and vermiculite, supplied with 0.5 g each of EcoLongTotal 70 and LongTotal 140 controlled-release fertilizers (JCAM AGRI, Tokyo, Japan). The calcareous pot experiment was carried out by transplanting 25- to 27-day-old seedlings of similar size (germinated as described above and then grown hydroponically for 6 days) into 1-l pots filled with calcareous soil48,54 (pH 8.5; Takaoka City, Toyama, Japan) supplied with 0.5 g each of EcoLongTotal 70 and LongTotal 140. The lower parts of the pots were submerged, but the soil surface was kept aerobic. The relative chlorophyll content of the expanded youngest leaf was measured using a SPAD-502 chlorophyll meter (Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan). A field soil culture was established at the experimental paddy field of Gyeongsang National University, Gyongnam, Korea (35°02′N, 128°03′E). The soil type was SiL with an approximate pH of 6.0. Rice seeds were germinated as described above, and the seedlings were transplanted into the paddy field. The field was fertilized with nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium following the normal practice in the region.

Quantitative RT–PCR analysis

Rice RNA was extracted from hydroponically grown roots or leaves, treated with DNase I and reverse-transcribed using a NucleoSpin RNA Plant Mini Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany), ReverTra Ace reverse transcriptase (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) and priming with oligo-d(T)17, or using an RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and ReverTra Ace qRT-PCR RT Master Mix with gDNA Remover (Toyobo). Real-time PCR was performed in a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with SYBR Green I and ExTaq Real-Time PCR version (Takara, Shiga, Japan) or with TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems). The transcript abundance was normalized against the rice α-2 tubulin transcript level, except for the analysis of IDEF1 dependence, which utilized the OsActin1 gene for normalization and was expressed as either the number of transcript copies per 1 μg of total RNA or a ratio relative to the levels in the NT or WT plants.

Metal-binding analysis of recombinant proteins

Full-length or truncated derivatives of the OsHRZ1 (AK288394), OsHRZ2 (AK068028) and BTS (At3g18290) coding regions were amplified by PCR using a complementary DNA pool of the rice cultivar Tsukinohikari or A. thaliana ecotype Columbia (Col-0) and ligated into pENTR/D-TOPO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA); the sequence was verified. The fragments were excised with restriction enzymes at the primer sites (underlined areas in Supplementary Table S2) and inserted into pMAL-c2 (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), constructing the HRZ or BTS derivatives in-frame downstream of MBP. The resulting plasmids, as well as pMAL-c2 itself (which expresses a MBP-LacZ fusion) as a negative control, were introduced into the E. coli strain BL21(DE3)pLysS. Recombinant proteins were obtained and purified using the MBP fusion system (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s instructions except that E. coli was cultured at 22–25 °C, and EDTA was omitted from the column buffer. The purity of the recombinant proteins was assessed by SDS–PAGE followed by Coomassie brilliant blue staining. Protein fractions containing considerable rates of bands with shorter molecular weights than expected were further purified by anion-exchange chromatography (Q-Sepharose; GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI) after desalting using a PD-10 column (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified proteins were quantified using a Bio-Rad Protein Assay Kit (Hercules, CA) and subjected to metal concentration analysis as follows. Approximately 0.1–1 mg (up to 2.5 ml) of purified protein solution was wet-ashed with 2 ml of 13.4 M HNO3 for 20 min at 220 °C using a MarsXpress oven (CEM, Matthews, NC). The Fe, Zn, Mn and Cu concentrations were measured by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICPS-8100; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The background metal content in the protein-free buffer was subtracted.

In vitro ubiquitination assay

An ubiquitination assay was carried out using the Ubiquitinylation Kit (ENZO Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY). Reactions (25 μl) containing 1 × ubiquitinylation buffer, 1 U of inorganic pyrophosphatase (Sigma, Madison, WI), 2.5 mM dithiothreitol, 1 × Mg-ATP solution, 100 nM human E1, 2.5 μM human E2 (UbcH5a), 100 nM E3 obtained as MBP fusions (see above) and 2.5 μM biotinylated ubiquitin were incubated at 37 °C for 55 min. The reactions were stopped by the addition of 25 μl of 2 × non-reducing gel loading buffer and analysed by SDS–PAGE followed by western blotting using either a streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase conjugate detection system (Vectastain Elite ABC Kit; Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA), or an anti-MBP primary antibody (Sigma; 1:1,500 dilution in Can Get Signal solution 1 (Toyobo)) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (GE Healthcare; 1:10,000 dilution in Can Get Signal solution 2 (Toyobo)). Detection was carried out using ECL Prime (GE Healthcare) and a LAS-3000 detector (Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan).

Generation of transgenic rice lines

To suppress HRZ expression by RNAi, a 320-bp fragment corresponding to the 3′-untranslated region of OsHRZ1, or a 335-bp fragment corresponding to the 3′-untranslated region and flanking coding region of OsHRZ2, was amplified by PCR using a complementary DNA pool of rice cultivar Tsukinohikari, inserted into pENTR/D-TOPO, and the sequence was verified. Using the LR Clonase reaction (Invitrogen), the fragment was transferred into the destination vector pIG121-RNAi-DEST14 to construct the HRZ-RNAi vector. Transformation of rice (cv. Tsukinohikari) was carried out as described55,56.

For complementation of the hrz2-1 line, the –1663 to –2 region from the translation start site of the barley IDS2 gene was amplified by PCR using the construct I2 (ref. 27) and ligated into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO (Invitrogen); the sequence was verified. The IDS2 promoter fragment was then replaced with the 35S promoter from pH7WGF2 (ref. 57) using HindIII and SpeI. Using the resulting plasmid (I2p-pH7WGF2) as the destination vector and OsHRZ1-pENTR/D-TOPO or OsHRZ2-pENTR/D-TOPO as the entry vector, the LR Clonase reaction was carried out, constructing in-frame fusions of the enhanced GFP-OsHRZ1 or -OsHRZ2 downstream of the IDS2 promoter. These vectors were transformed into the hrz2-1 line.

Analysis of rice metal concentrations

Roots, leaves and straws were dried for 2–3 days at 70 °C, and portions of 50–200 mg were wet-ashed with 1.5 ml of 13.4 M HNO3 and 1.5 ml of 8.8 M H2O2 for 20 min at 220 °C using a MarsXpress oven. Brown and polished rice seeds were prepared as described44. Metal concentration measurement was carried out as described above.

Microarray analysis

Hydroponically grown roots of NT and HRZ2i lines were used to prepare total RNA with a NucleoSpin RNA Plant Mini Kit (Macherey-Nagel). The rice 44 K microarray (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) used contains 43,144 unique 60-mer oligonucleotides synthesized based on sequence data from the Rice Full-length cDNA Project ( http://cdna01.dna.affrc.go.jp/cDNA/). Microarray hybridization, scanning and data analysis were performed as described13. Whole data sets of the 44 K microarray analysis have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus58 and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE39906.

GFP observation

For subcellular localization, the LR Clonase reaction was carried out using the pH7WGF2 plasmid and OsHRZ1-pENTR/D-TOPO, OsHRZ2-pENTR/D-TOPO or BTS-pENTR/D-TOPO. Transient gene expression in onion (Allium cepa) bulb epidermal cells was carried out as described59. Fluorescence observation of the transient and stable transformants was carried out using a LSM5 Pascal laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Cell-free degradation assay

The recombinant MBP-HRZ proteins and rice plants (cultivar Nipponbare) were prepared as described above. Protein extraction, quantification and degradation reaction were carried out as described previously28,60 with modifications in the reaction conditions described in the legend to Fig. 8. For MG132 treatment, 10 mM ready-made solution (Sigma) was used. Western blotting was carried out using anti-MBP antibody as described above.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using Microsoft Excel software. For each set of comparisons, a two-sample Student’s t-test for equal or unequal variance was carried out based on an F-test for equal variance (significance level=0.05). The results are summarized in Supplementary Table S1.

Author contributions

T.K., S.N., H.N. and N.K.N. designed the research. T.K. carried out the experiments with assistance from T.S., R.N.I. and H.N. T.K. analysed the data. T.K. wrote the manuscript with contributions and discussion from all of the co-authors.

Additional information

Accession codes: Whole data sets of the 44 K microarray analysis have been deposited in the NCBI Gene. The microarray data has been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus58 under accession code GSE39906.

How to cite this article: Kobayashi, T. et al. Iron-binding haemerythrin RING ubiquitin ligases regulate plant iron responses and accumulation. Nat. Commun. 4:2792 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3792 (2013).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures S1-S10 and Supplementary Tables S1-S2

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yoshiaki Nagamura and Ms. Ritsuko Motoyama (National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences) for the rice 44 K microarray analysis; the Rice Genome Resource Centre (National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences) for providing the Tos17 line; Dr. Gynheung An (Kyung Hee University) for providing the T-DNA insertion lines; Dr. Ryuichi Takahashi, Dr. Yasuhiro Ishimaru, Ms. Lixia Zhang (The University of Tokyo), Dr. Hongchun Xiong (China Agricultural University), Dr. Hiroshi Masuda, Ms. Akane Konishi and Ms. May Linn Aung (Ishikawa Prefectural University) for assistance with the rice cultures and analysis; Dr. Satoshi Mori (NPO-WINEP) for valuable discussions; and Dr. Khurram Bashir (RIKEN) for critically reading the manuscript and valuable discussions. This research was supported by the Japan Science and Technology Agency program PRESTO (to T.K.) and in part by a Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (23248011, to N.K.N.).

References

- Mayer J. E., Pfeiffer W. H. & Beyer P. Biofortified crops to alleviate micronutrient malnutrition. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 166–170 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschner H. Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants 2nd edn. Academic press: London, UK, (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Römheld V. & Marschner H. Evidence for a specific uptake system for iron phytosiderophore in roots of grasses. Plant Physiol. 80, 175–180 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi S. Naturally occuring iron-chelating compounds in oat- and rice-root washing. I. Activity measurement and preliminary characterization. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 22, 423–433 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T. & Nishizawa N. K. Iron uptake, translocation, and regulation in higher plants. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 63, 131–152 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindt M. N. & Guerinot M. L. Getting a sense for signals: regulation of the plant iron deficiency response. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1823, 1521–1530 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T. et al. The rice transcription factor IDEF1 directly binds to iron and other divalent metals for sensing cellular iron status. Plant J. 69, 81–91 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long T. A. et al. The bHLH transcription factor POPEYE regulates response to iron deficiency in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell 22, 2219–2236 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenkamp R. E. Dioxygen and Hemerytherin. Chem. Rev. 94, 715–726 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- French C. E., Bell J. M. & Ward F. B. Diversity and distribution of hemerythrin-like proteins in prokaryotes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 279, 131–145 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vashisht A. et al. Control of iron homeostasis by an iron-regulated ubiquitin ligase. Science 326, 718–721 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salahudeen A. A. et al. An E3 ligase possessing an iron-responsive hemerythrin domain is a regulator of iron homeostasis. Science 326, 722–726 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogo Y. et al. Isolation and characterization of IRO2, a novel iron-regulated bHLH transcription factor in graminaceous plants. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 2867–2878 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogo Y. et al. The rice bHLH protein OsIRO2 is an essential regulator of the genes involved in Fe uptake under Fe-deficient conditions. Plant J. 51, 366–377 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogo Y. et al. OsIRO2 is responsible for iron utilization in rice and improves growth and yield in calcareous soil. Plant Mol. Biol. 75, 593–605 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L. et al. Identification of a novel iron regulated basic helix-loop-helix protein involved in Fe homeostasis in Oryza sativa. BMC Plant Biol. 10, 166 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vierstra R. D. The ubiquitin-26S proteasome system at the nexus of plant biology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 385–397 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua Z. & Vierstra R. D. The Cullin-RING ubiquitin-protein ligases. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 62, 299–334 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamsjaeger R., Liew C. K., Loughlin F. E., Crossley M. & Mackay J. P. Sticky fingers: zinc-fingers as protein-recognition motifs. Trends Biochem. Sci. 32, 63–70 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieker L. C., Stenkamp R. E., Jensen L. H., Prickril B. & LeGall J. Structure of rubredoxin from the bacterium Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. FEBS Lett. 208, 73–76 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElver J. et al. Insertional mutagenesis of genes required for seed development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 159, 1751–1763 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogo Y. et al. A novel NAC transcription factor IDEF2 that recognizes the iron deficiency-responsive element 2 regulates the genes involved in iron homeostasis in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 13407–13417 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y. et al. RiceXPro: a platform for monitoring gene expression in japonica rice grown under natural field conditions. Nuc. Acids Res. 39, D1141–D1148 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y. et al. Field transcriptome revealed critical developmental and physiological transitions involved in the expression of growth potential in japonica rice. BMC Plant Biol. 11, 10 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T. et al. The transcription factor IDEF1 regulates the response to and tolerance of iron deficiency in plants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 19150–19155 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T. et al. The rice transcription factor IDEF1 is essential for the early response to iron deficiency, and induces vegetative expression of late embryogenesis abundant genes. Plant J. 60, 948–961 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T. et al. Construction of artificial promoters highly responsive to iron deficiency. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 50, 1167–1175 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Wang F. et al. Biochemical insights on degradation of Arabidopsis DELLA protein gained from a cell-free assay system. Plant Cell 21, 2378–2390 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S., Kurtz D. M. Jr, Liu Z. J., Rose J. & Wang B. C. Displacement of iron by zinc at the diiron site of Desulfovibrio vulgaris rubrerythrin: x-ray crystal structure and anomalous scattering analysis. J. Inorg. Biochem. 98, 786–796 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.-H. & Kurtz D. M. Jr Metal substitutions at the diiron sites of hemerythrin and myohemerythrin: contributions of divalent metals to stability of a four-helix bundle protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 89, 7065–7069 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demuynck S., Li K. W., Schors R. V. & Dhainaut-Courtois N. Amino acid sequence of the small cadmium-binding protein (MP II) from Nereis diversicolor (annelida, polychaeta). Evidence for a myohemerythrin structure. Eur. J. Biochem. 217, 151–156 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori S. et al. Why are young rice plants highly susceptible to iron deficiency? Plant Soil. 130, 143–156 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K. et al. Formate dehydrogenase, an enzyme of anaerobic metabolism, is induced by Fe-deficiency in barley roots. Plant Physiol. 116, 725–732 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H., Nakanishi H., Nishizawa N. K. & Mori S. Induction of the IDI1 gene in Fe-deficient barley roots: a gene encoding putative enzyme that catalyses the methionine salvage pathway for phytosiderophore production. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 46, 1–9 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Sauter M., Lorbiecke R., OuYang B., Pochapsky T. C. & Rzewuski G. The immediate-early ethylene response gene OsARD1 encodes an acireductone dioxygenase involved in recycling of the ethylene precursor S-adenosylmethionine. Plant J. 44, 718–729 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. et al. Ethylene is involved in the regulation of iron homeostasis by regulating the expression of iron-acquisition-related genes in Oryza sativa. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 667–674 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouault T. A. An ancient gauge for iron. Science 326, 676–677 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura K., Nomura M., Tajima S. & Kouchi H. LjnsRING, a novel RING finger protein, is required for symbiotic interactions between Mesorhizobium loti and Lotus japonicus. Plant Cell Physiol. 47, 1572–1581 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji Y. et al. Inhibitory effect on the tobacco mosaic virus infection by a plant RING finger protein. Virus Res. 153, 50–57 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto F., Yoshihara T., Shigemoto N., Toki S. & Takaiwa F. Iron fortificaton of rice seed by the soybean ferritin gene. Nat. Biotech. 17, 282–286 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. et al. Iron fortification of rice seeds through activation of the nicotianamine synthase gene. Proc. Natl Acad Sci. USA 106, 22014–22019 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda H. et al. Overexpression of the barley nicotianamine synthase gene HvNAS1 increases iron and zinc concentrations in rice grains. Rice 2, 155–166 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M. et al. Transgenic rice lines that include barley genes have increased tolerance to low iron availability in a calcareous paddy soil. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 54, 77–85 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Masuda H. et al. Increase in iron and zinc concentrations in rice grains via the introduction of barley genes involved in phytosiderophore synthesis. Rice 1, 100–108 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru Y. et al. Rice metal-nicotianamine transporter, OsYSL2, is required for the long-distance transport of iron and manganese. Plant J. 62, 379–390 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda H. et al. Iron biofortification in rice by the introduction of multiple genes involved in iron nutrition. Sci. Rep. 2, 543 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda H. et al. Iron-biofortification in rice by the introduction of three barley genes participated in mugineic acid biosynthesis with soybean ferritin gene. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 132 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru Y. et al. Mutational reconstructed ferric chelate reductase confers enhanced tolerance in rice to iron deficiency in calcareous soil. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 7373–7378 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter S. et al. InterPro in 2011: new developments in the family and domain prediction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D306–D312 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G. & Gibson T. J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T. et al. Expression of iron-acquisition-related genes in iron-deficient rice is co-ordinately induced by partially conserved iron-deficiency-responsive elements. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 1305–1316 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong D. H. et al. T-DNA insertional mutagenesis for activation tagging in rice. Plant Physiol. 130, 1636–1644 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyao A. et al. Target site specificity of the Tos17 retrotransposon shows a preference for insertion within genes and against insertion in retrotransposon-rich regions of the genome. Plant Cell 15, 1771–1780 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M., Nakanishi H., Kawasaki S., Nishizawa N. K. & Mori S. Enhanced tolerance of rice to low iron availability in alkaline soils using barley nicotianamine aminotransferase genes. Nat. Biotech. 19, 466–469 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiei Y., Ohta S., Komari T. & Kumashiro T. Efficient transformation of rice (Oryza sativa L.) mediated by Agrobacterium and sequence analysis of the boundaries of the T-DNA. Plant J. 6, 271–282 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T. et al. In vivo evidence that Ids3 from Hordeum vulgare encodes a dioxygenase that converts 2’-deoxymugineic acid to mugineic acid in transgenic rice. Planta 212, 864–871 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M., Inze D. & Depicker A. Gateway vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Trends Plant Sci. 7, 193–195 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R., Domrachev M. & Lash A. E. Gene expression omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acid Res. 30, 207–210 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno D. et al. Three nicotianamine synthase genes isolated from maize are differentially regulated by iron nutritional status. Plant Physiol. 132, 1989–1997 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q. et al. Rice APC/CTE controls tillering by mediating the degradation of MONOCULM 1. Nat. Commun. 3, 752 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1-S10 and Supplementary Tables S1-S2