Ethanol abuse and chronic ethanol consumption are major causes of liver disease and represent a significant health problem in the United States and worldwide. An early manifestation of alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is the presence of fatty liver (hepatic steatosis) that, with continued insult, can progress to alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis1. A hepatocellular organelle central to the progression of these disease states is the lipid droplet (LD), a sphere of triglycerides encased in a phospholipid monolayer (for reviews see2,3). The excessive formation and accumulation of LDs within the hepatocyte is a defining feature of steatosis. Despite the fact that LDs are central to hepatic steatosis, the mechanisms that support the formation and metabolism of these organelles are only partially understood. As most patients that abuse alcohol display some degree of hepatic steatosis, it seems essential that we define how LD metabolism is altered by both acute or chronic alcohol exposure and how this leads to hepatocellular damage.

As fat accumulation can influence the liver’s sensitivity to important triggers such as oxidative and ER stress, as well as the production and accumulation of endotoxins4,5, the aberrant accumulation of lipids in hepatocytes could easily act as the “first hit” in the progression of ALD1 and might therefore provide a prime target for therapeutic intervention. In this short essay we discuss the concept that LDs in hepatocytes are complex and dynamic organelles that appear to reside in a state of flux between formation and fusion or, conversely, metabolism and vesiculation. This equilibrium is mediated by a variety of different membrane-associated proteins, some of which may be unique to LDs while others appear to be components of the secretory and endocytic membrane trafficking machinery. We propose that these proteins act to vesiculate LDs in a regulated fashion to facilitate lipid metabolism, and that alcohol exposure appears to attenuate this process, leading to the accumulation of LDs that potentiates hepatic steatosis.

LD Dynamics in Hepatocytes

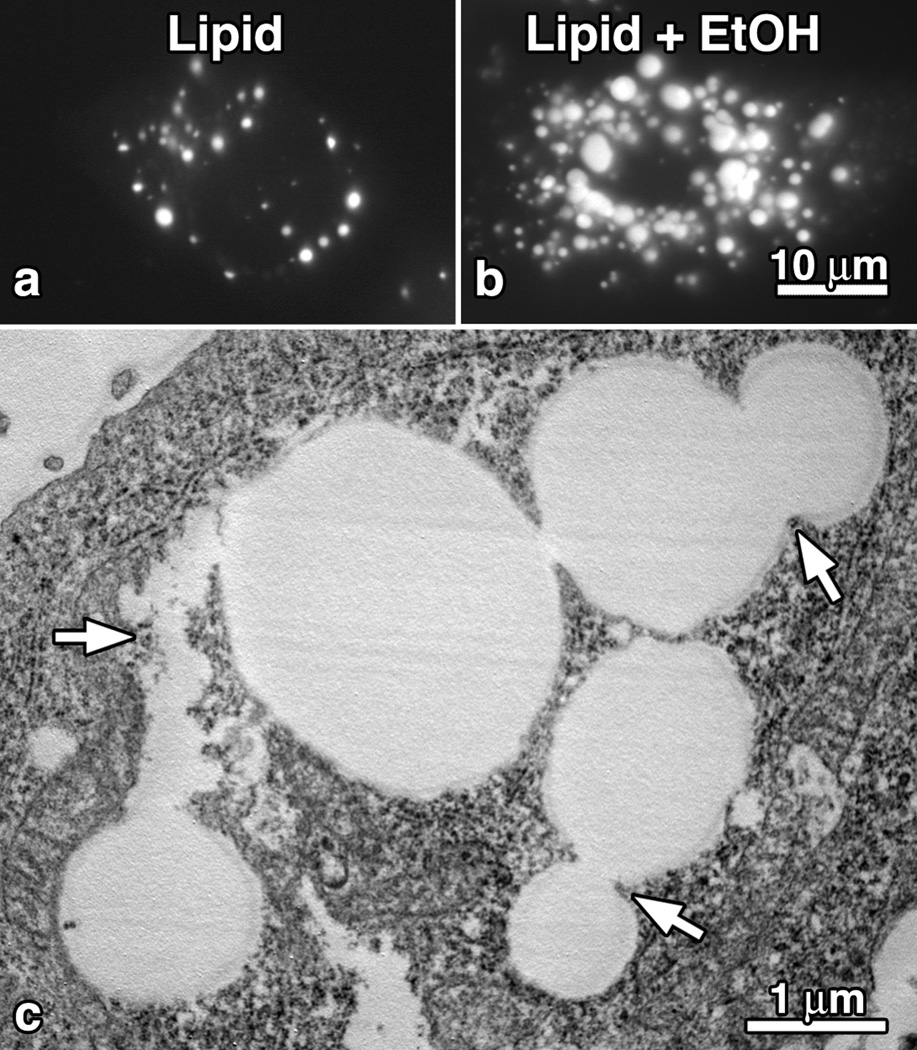

In hepatocytes, there can be an expansive increase in LD number and size by the continued synthesis and accumulation of esterified lipids from lipid-modifying enzymes associated with the surrounding monolayer and/ or the trafficking and subsequent fusion of smaller lipid droplets. In general, the expansion of lipid droplet growth is relatively modest in cultured hepatocytes under normal serum conditions. However, cells exposed to 200 µM oleic acid alone or in combination with 100 mM ethanol show a dramatic increase in lipid droplet size and number, particularly in the perinuclear regions (Fig. 1). This dramatic response occurs in isolated rat hepatocytes exposed to alcohol in culture, hepatocytes isolated from alcohol-pair fed rats, the WIF-B hepatocyte model that maintains polarized characteristics and can metabolize alcohol, as well as VA-13 cells, a stable HepG2 cell line transfected to express alcohol dehydrogenase. Importantly, all of these cell models display a 2-fold to 4-fold increase in LD size in response to alcohol. This may represent either an aberrant increased lipid synthesis and storage or an attenuation in LD vesiculation and breakdown. The fact that LD number and size are maintained in alcohol-treated hepatocytes for prolonged periods of time even when “starved” in serum-free medium suggests that LD vesiculation and lipolysis are indeed compromised upon alcohol exposure (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Lipid Droplets are Dynamic Organelles that Maintain a Fission and Fusion Equilibrium. (a,b) Fluorescence microscopy of VA-13 cells that were incubated in 200 µM oleic acid (OA) for 15 hours in the absence (A) or presence (B) of 100 mM ethanol and stained with Oil Red O. Note the marked increase in LD size and number induced by the ethanol exposure. (C) Electron microscopy of ethanol treated, OA fed, VA-13 cells showing large LDs undergoing multiple fission and/or fusion events (arrows).

Membrane Dynamics Contributing to Lipid Droplet Vesiculation and Lipolysis

The mechanisms by which lipid bilayers are deformed and vesiculated to support the endocytic and secretory pathways in the hepatocyte are well studied (for reviews see6,7). Although LDs are encased in a lipid monolayer, it is reasonable to predict that many components utilized to tubulate the plasma membrane, endosomes, and the Golgi apparatus could also be recruited to LDs to mediate LD breakdown. This vesiculation process could facilitate lipolysis by greatly increasing the surface to volume ratio of LDs and thereby allow greater access of the lipases, lysosomes and autophagosomes required for lipid metabolism. Such a vesiculation machinery appears to be conserved and widely used throughout epithelial cells. It consists of the large GTPase Dynamin that functions as a membrane pinchase and acts in concert with the actin cytoskeleton, membrane coat proteins and associated structural adaptors, small GTPases such as Rabs and Arfs that act as molecular switches, and a variety of BAR-domain containing proteins that are capable of bending membranes. It is attractive to postulate that these components could be recruited to the LD surface to deform and break the LD monolayer not unlike what occurs during the endocytosis or secretion. Importantly, this process could be compromised by alcohol, leading to the observed accumulation of LDs.

The concept of similarities between the LD and endocytic machineries gains support from several interesting observations generated by a variety of different laboratories. For example, Caveolin-1 (Cav1), is an essential component of caveolae and has been identified in the LD proteome8. A functional interaction of Cav-1 with LDs has been reported in hepatocytes and, interestingly, hepatocytes from Cav1−/− mice show reduced LD accumulation after partial hepatectomy9. The related family member Cav2 has also been shown to associate with LDs but no functional insights have been provided so far10. Whether assembled caveolae, or the Cav1 protein, act in the formation or the vesiculation of LDs in the hepatocyte needs to be established.

In addition to caveolae, several small Rab GTPases have been implicated in LD function. Rabs also bind membrane lipids and act as molecular switches to support the targeted transport, docking, and fusion of a donor vesicle to a receptor compartment11. Rab5 supports the fusion of early endosomes12, while Rab7 performs a similar function between the late endosome and lysosome13. Both of these Rabs have been observed to associate with LDs14, while proteomic studies of LD-associated proteins have identified more than a dozen other Rab proteins. Currently, the contributions these enzymes make to LD dynamics are almost totally undefined.

Most recently, LD metabolism has been linked to the autophagic process in hepatocytes as LD content is delivered to lysosomes and autophagosomes while inhibition of this pathway results in the accumulation of triglycerides15. The autophagic pathway is well known to utilize many components of secretory and endocytic machinery16 and could be a target for ethanol-induced damage.

Alcohol-Induced Perturbations of LD Metabolism

Could ethanol exposure alter the vesiculation, trafficking, and degradation of LDs in hepatocytes? Several studies have identified multiple ethanol-induced impairments of vesicle-based transport in the hepatocyte such as clathrin- mediated endocytosis17,18, including traffic of the hepatocyte-specific asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGP-R) resulting in altered receptor-ligand binding, internalization, uncoupling of receptor-ligand complexes in endosomes, and degradation by lysosomes19. Alcohol exposure also results in a marked retention of nascent proteins in the Golgi apparatus of the hepatocyte along with a displacement of Rab2 from this compartment20. These inhibitory effects are likely potentiated by the toxic metabolites of ethanol such as acetaldehyde that has been shown to form inhibitory adducts with cellular proteins and enzymes essential to these pathways, such as the microtubule cytoskeleton21,22. Therefore, it is likely that adduct formation perturbs the enzymatic activity of other GTPases in addition to tubulin, such as the dynamins and Rab proteins, to lead to an impairment of LD degradation. Indeed, it is well documented that alcohol can disrupt lysosomal and proteosomal protein degradation23, as well as autophagic activity24. In contrast, a recent study has shown that acute ethanol exposure actually stimulates autophagic degradation of both mitochondria and LDs in treated hepatocytes and could provide a protective benefit to the effects of oxidative stress as experimental disruption of this autophagic response leads to apoptosis 25. It will be important to define how acute alcohol exposure might lead to these differential responses and whether they are further potentiated by a high lipid environment.

Important Directions for Future Study

In this essay we have provided a very brief overview of how membrane traffic might regulate to LD dynamics in the hepatocyte. Novel concepts that we believe are worthy of experimental pursuit suggest that, first, LDs are dynamic organelles that are reduced in size by vesiculation to facilitate lipolysis. Second, this process is mediated by many of the same membrane trafficking components used at other secretory and endocytic organelles in the hepatocyte. Finally, this vesiculation-supported lipolysis is compromised by both acute and chronic ethanol exposure leading to LD accumulation and steatosis. Superimposed on these predictions is the central issue of how LD dynamics contribute to hepatocellular stress, injury and cirrhosis. The encapsulation of triglycerides into large droplets could be viewed as a protective mechanism by the hepatocyte to remove reactive lipid species that can potentiate oxidative stress, ER stress, and the release of inflammatory cytokines. Thus, LD accumulation per se, either by alcohol or in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, may not necessarily induce hepatocellular damage directly but rather it may be the subsequent metabolism of these LDs that proves injurious. How the excessive accumulation of LDs in the steatotic liver eventually overwhelms the protective mechanisms of hepatocyte is a seminal question in need of attention.

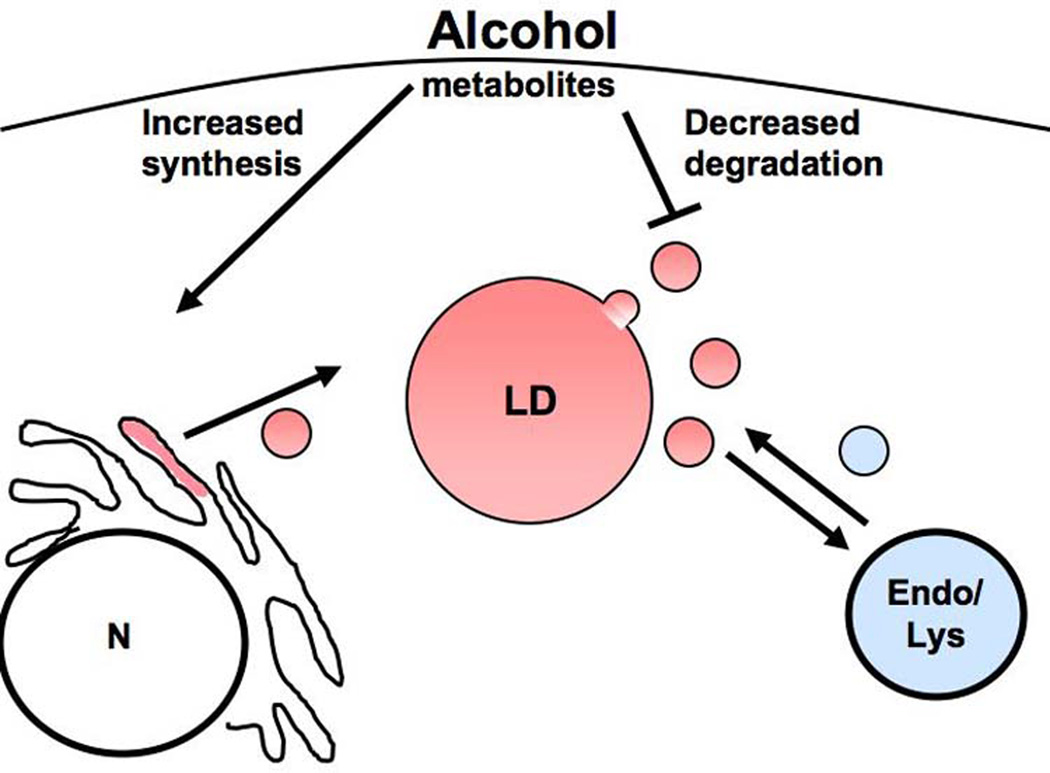

Fig. 2.

The number and size of LDs in the hepatocyte is maintained by a vesicle trafficking-based equilibrium of synthesis and lipolysis. Illustration depicting how ETOH could contribute to steatosis via increased LD formation from the endoplasmic reticulum and/or decreased metabolism, vesiculation, and interaction with degradative compartments such as the endosome/lysosome and autophagosome (not shown).

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH Challenge Grant AA19032 to MAM and CAC and the Optical Microscopy Core of the Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology (P30DK084567).

Abbreviations

- ALD

alcoholic liver disease

- Cav

caveolin

- LD

lipid droplets

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1.Day CP, James OF. Hepatic steatosis: innocent bystander or guilty party? Hepatology. 1998;27:1463–1466. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krahmer N, Guo Y, Farese RV, Jr, Walther TC. SnapShot: lipid droplets. Cell. 2009;139:1024. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo Y, Cordes KR, Farese RV, Jr, Walther TC. Lipid droplets at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:749–752. doi: 10.1242/jcs.037630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu Y, Zhuge J, Wang X, Bai J, Cederbaum AI. Cytochrome P450 2E1 contributes to ethanol-induced fatty liver in mice. Hepatology. 2008;47:1483–1494. doi: 10.1002/hep.22222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang S, Lin H, Diehl AM. Fatty liver vulnerability to endotoxininduced damage despite NF-kappaB induction and inhibited caspase 3 activation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G382–G392. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.2.G382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schroeder B, McNiven MA. Endocytosis as an essential process in liver function and pathology. In: Arias I, editor. The Liver: Biology and Pathobiology. 5th ed. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2009. pp. 107–123. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chi S, McNiven MA. Membrane transport in hepatocellular secretion. In: Arias I, editor. The Liver: Biology and Pathobiology. 5th ed. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2009. pp. 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Lay S, Hajduch E, Lindsay MR, Le Liepvre X, Thiele C, Ferre P, et al. Cholesterol-induced caveolin targeting to lipid droplets in adipocytes: a role for caveolar endocytosis. Traffic. 2006;7:549–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernandez MA, Albor C, Ingelmo-Torres M, Nixon SJ, Ferguson C, Kurzchalia T, et al. Caveolin-1 is essential for liver regeneration. Science. 2006;313:1628–1632. doi: 10.1126/science.1130773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujimoto T, Kogo H, Ishiguro K, Tauchi K, Nomura R. Caveolin-2 is targeted to lipid droplets, a new"membrane domain" in the cell. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:1079–1085. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.5.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stenmark H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:513–525. doi: 10.1038/nrm2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorvel JP, Chavrier P, Zerial M, Gruenberg J. rab5 controls early endosome fusion in vitro. Cell. 1991;64:915–925. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90316-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vitelli R, Santillo M, Lattero D, Chiariello M, Bifulco M, Bruni CB, et al. Role of the small GTPase Rab7 in the late endocytic pathway. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4391–4397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu P, Bartz R, Zehmer JK, Ying YS, Zhu M, Serrero G, et al. Rabregulated interaction of early endosomes with lipid droplets. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:784–793. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh R, Kaushik S, Wang Y, Xiang Y, Novak I, Komatsu M, et al. Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:1131–1135. doi: 10.1038/nature07976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie Z, Klionsky DJ. Autophagosome formation: core machinery and adaptations. Nature Cell Biol. 2007;9:1102–1109. doi: 10.1038/ncb1007-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernandez DJ, McVicker BL, Tuma DJ, Tuma PL. Ethanol selectively impairs clathrin-mediated internalization in polarized hepatic cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78:648–655. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McVicker BL, Casey CA. Effects of ethanol on receptor-mediated endocytosis in the liver. Alcohol. 1999;19:255–260. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(99)00043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casey CA, Kragskow SL, Sorrell MF, Tuma DJ. Chronic ethanol administration impairs the binding and endocytosis of asialo-orosomucoid in isolated hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:2704–2710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larkin JM, Oswald B, McNiven MA. Ethanol-induced retention of nascent proteins in rat hepatocytes is accompanied by altered distribution of the small GTP-binding protein rab2. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2146–2157. doi: 10.1172/JCI119021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shepard BD, Fernandez DJ, Tuma PL. Alcohol consumption impairs hepatic protein trafficking: mechanisms and consequences. Genes Nutr. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s12263-009-0156-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shepard BD, Joseph RA, Kannarkat GT, Rutledge TM, Tuma DJ, Tuma PL. Alcohol-induced alterations in hepatic microtubule dynamics can be explained by impaired histone deacetylase 6 function. Hepatology. 2008;48:1671–1679. doi: 10.1002/hep.22481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donohue TM, Jr, Osna NA. Intracellular proteolytic systems in alcohol- induced tissue injury. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27:317–324. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donohue TM., Jr Autophagy and ethanol-induced liver injury. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1178–1185. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding WX, Li M, Chen X, Ni HM, Lin CW, Gao W, et al. Autophagy reduces acute ethanol-induced hepatotoxicity and steatosis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1740–1752. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]