This is the first study to investigate IBC in terms of hormone receptor and HER2 subtypes and to determine associated treatment efficacy in a large dataset. Classifying IBC patients into two distinct subtypes, TNBC and non-TNBC, predicts long-term prognosis. HR-positive disease, irrespective of HER2 status, had poorer prognosis that did not differ from that of the HR-negative/HER2-positive subtype.

Keywords: inflammatory breast cancer, HER2, hormonal receptor, breast neoplasm, prognosis factor, subtype

Abstract

Background

Subtypes defined by hormonal receptor (HR) and HER2 status have not been well studied in inflammatory breast cancer (IBC). We characterized clinical parameters and long-term outcomes, and compared pathological complete response (pCR) rates by HR/HER2 subtype in a large IBC patient population. We also compared disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) between IBC patients who received targeted therapies (anti-hormonal, anti-HER2) and those who did not.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively reviewed the records of patients diagnosed with IBC and treated at MD Anderson Cancer Center from January 1989 to January 2011. Of those, 527 patients had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and had available information on estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2 status. HR status was considered positive if either ER or PR status was positive. Using the Kaplan–Meier method, we estimated median DFS and OS durations from the time of definitive surgery. Using the Cox proportional hazards regression model, we determined the effect of prognostic factors on DFS and OS. Results were compared by subtype.

Results

The overall pCR rate in stage III IBC was 15.2%, with the HR-positive/HER2-negative subtype showing the lowest rate (7.5%) and the HR-negative/HER2-positive subtype, the highest (30.6%). The HR-negative, HER2-negative subtype (triple-negative breast cancer, TNBC) had the worst survival rate. HR-positive disease, irrespective of HER2 status, had poor prognosis that did not differ from that of the HR-negative/HER2-positive subtype with regard to OS or DFS. Achieving pCR, no evidence of vascular invasion, non-TNBC, adjuvant hormonal therapy, and radiotherapy were associated with longer DFS and OS.

Conclusions

Hormone receptor and HER2 molecular subtypes had limited predictive and prognostic power in our IBC population. All molecular subtypes of IBC had a poor prognosis. HR-positive status did not necessarily confer a good prognosis. For all IBC subtypes, novel, specific treatment strategies are needed in the neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings.

introduction

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC), with its clinical and biological characteristics of rapid proliferation, is the most aggressive form of breast cancer [1]. The incidence of IBC in the USA has been reported to range from 1% to 5% of breast cancer [2]. However, the recurrence and mortality rates for IBC are quite high compared with those of noninflammatory locally advanced breast cancer; IBC causes 8%–10% of all breast cancer-related deaths [2].

Hormonal receptor (HR) and HER2 status are the most important prognostic factors for breast cancer, as well as the strongest predictors of treatment response. These markers predict biological behaviors of the tumor and allow classification of breast cancer into clinically relevant subtypes. HER2 is the best-established target in breast cancer, and HER2-targeted therapies have been indispensable for breast cancer treatment and improving clinical outcomes. However, these markers have only been studied in small populations of IBC patients. Although several studies have addressed the natural history and outcomes of IBC [2–4], all of the studies lack information about HER2 status or tumor subtypes based on both HR status and HER2 status. The largest population-based studies to date used multi-institutional databases or SEER data, which may explain why it was difficult to collect information such as HER2 status in a consistent manner. Only two studies [5, 6], carried out at our institution, have examined both HR and HER2 status in patients with IBC. However, an analysis by subtype could not be carried out in one study because of its small sample size (n = 398), and the other study focused specifically on triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and locoregional relapse in stage III IBC (n = 316). We, therefore, decided to conduct a wider investigation of both HR and HER2 status, using the world's largest clinical dataset of IBC patients, to determine the impact of HR/HER2 subtypes on the clinical course of disease.

In this study, we specifically focused on patients for whom information on estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2 status was available and who received multidisciplinary treatment at MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDA). The objectives of this study were to determine the long-term outcome of IBC by HR/HER2 subtype; to determine whether sensitivity to neoadjuvant systemic therapy differed among patients by subtype; to determine the correlation between clinical parameters and clinical outcomes, such as disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS), in IBC; and to compare DFS and OS between IBC patients who received targeted therapies (anti-hormonal, anti-HER2) and those who did not.

patients and methods

patients

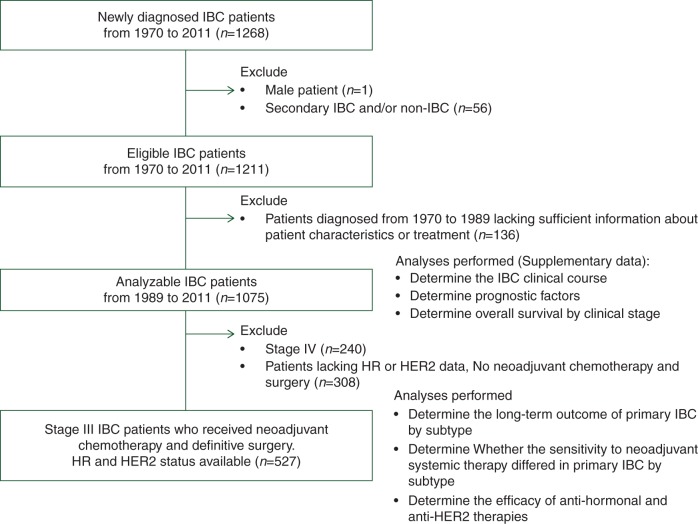

Figure 1 shows the patient population analyzed in this study. We reviewed the institutional tumor registry, the breast cancer electronic medical record management system, and nonelectronic clinical trial records at MDA for patients diagnosed with IBC between 24 February 1970, and 27 January 2011 (n = 1268). A clinical diagnosis of IBC required the presence of diffuse erythema, heat ridging, or peau d'orange [corresponding to classification T4d in the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) system]. All the cases were evaluated at the time of diagnosis and confirmed as IBC by a multidisciplinary team. We excluded from the current analysis male patients (n = 1) and patients with secondary IBC and/or suspected non-IBC (n = 56); we defined secondary IBC as any IBC that occurred after non-IBC presentation or IBC noted as ‘secondary IBC’ in the medical record. We also excluded patients with incomplete records on clinical characteristics and treatment (n = 136). For the remaining 1075 patients, we analyzed the IBC clinical course, prognostic factors, and overall survival by clinical stage; these data are presented as supplementary information, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient population.

For the HR/HER2 subtype analysis, we excluded patients who did not have ER, PR, and HER2 status available. Therefore, the final analytic cohort consisted of 527 women diagnosed with primary stage III IBC after 1 January 1989, who had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and underwent definitive surgery and who had sufficient data for analysis of HR/HER2 subtype.

Age, menopausal status, body mass index (BMI), ethnicity, clinical stage, nuclear grade, and estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) status were extracted from the medical records. ER and PR status had been determined with immunohistochemistry with a cutoff of 10% of cells staining positively considered a positive result. We identified the HR status as positive (HR+) if ER, PR, or both ER and PR were positive and as negative (HR−) if both ER and PR were negative. The HER2 status was considered negative (HER2−) if (i) IHC results were 0 to +1 or (ii) IHC results were +2 and FISH results were negative. The HER2 status was considered positive (HER2+) if (i) IHC results were +3 and FISH results were not available, or (ii) the FISH result was positive (amplification ratio ≥2.0) regardless of the IHC result. We defined definitive surgery as surgery carried out within 1 year of diagnosis. Lymphatic invasion and vascular invasion were determined to be present if documented in the pathology report after surgery. Pathological complete response (pCR) was defined as no evidence of invasive carcinoma in the breast and the axillary lymph nodes at the time of surgery [7]. The MDA Institutional Review Board approved the protocol for this study (PA11-1129) and granted a waiver of informed consent based on the study's retrospective nature.

statistical analysis

survival analysis

The primary end points of this study were OS time from two different time intervals, the intervals from the date of diagnosis and from the date of definitive surgery to the date of death due to any cause or the last follow-up date, and DFS time from the date of definitive surgery to the date of recurrence from the original cancer. Patients who died before disease recurrence were censored at the time of death. Stages III and IV were analyzed separately for OS. (supplementary Figure S3, available at Annals of Oncology online.) Data were first summarized using standard and descriptive statistics and frequency tabulation. OS was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the comparisons between or among patient characteristic groups were assessed using the log-rank test. Both univariate and multicovariate Cox proportional hazard models were applied to assess the effect of covariates of interest on OS and DFS. We estimated the hazard ratio for each potential prognostic factor with a 95% confidence interval (CI). All computations were carried out in SAS 9.3 and S-PLUS 8.2 software.

subtype analysis

Patients were divided into four groups by their HR and HER2 status: HR+/HER2−, HR+/HER2+, HR−/HER2+, and HR−/HER2− (i.e. TNBC). Patient characteristics were tabulated and compared among these subtypes. We investigated the relationship between these subtypes and pCR rate as well as clinical outcomes obtained with the standard multidisciplinary treatment of each subtype.

results

analyses for all 1075 IBC patients

The clinical characteristics and prognostic factors for all 1075 patients are shown in supplementary Table S2, S3A–C, available at Annals of Oncology online.

analyses for patients with known receptor status

patient characteristics

A total of 527 patients with primary IBC received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, underwent definitive surgery, and had evaluable status for ER, PR, and HER2. Table 1 shows the patient characteristics for each receptor subtype. Among this group, 78 patients (14.8%) had HR-positive/HER2-positive disease; 188 (35.7%), HR-positive/HER2-negative; 122 (23.1%), HR-negative/HER2-positive; and 139 (26.4%), TNBC. The four subgroups did not differ significantly in age, BMI, ethnicity, or menopausal status. There were no differences by subtype in clinical node status or lymphatic invasion. However, increased vascular invasion was evident in both the HR-positive/HER2-negative (38.9%) and TNBC subtypes (28%). Further, among patients with nuclear grade I/II disease, 60.6% were in the HR-positive/HER2-negative subtype, and among those with nuclear grade III disease, 31.6% were in the TNBC subtype. For chemotherapy, 17% of patients received an anthracycline regimen; 72% an anthracycline + taxane regimen, 3% a taxane regimen, and 9% a taxane + trastuzumab regimen. Statistically, we found no differences in distribution of the anthracycline and anthracycline + taxane regimens among the four groups. Among patients with HR-positive disease, 72% received adjuvant hormonal therapy, and those who did not had disease progression before completing the therapy. In HER2-positive disease, 55% of patients received trastuzumab as part of their neoadjuvant chemotherapy in clinical trials; the remainder of patients did not because the treatment was unavailable at the time of their treatment. About 86% of patients received neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant radiotherapy.

Table 1.

Patient clinicopathological characteristics by subtype (N = 527)

| Covariate | Levels | HR/HER2 status |

P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNBC | HR−/HER2+ | HR+/HER2− | HR+/HER2+ | |||

| 139 (26.4%) | 122 (23.1%) | 188 (35.7%) | 78 (14.8%) | |||

| Patient factors | ||||||

| Age (median), year | 51.26 | 50.39 | 49.97 | 48.71 | 0.482 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | <25 | 46 | 23 | 41 | 16 | 0.133 |

| 25–29 | 35 | 38 | 58 | 29 | ||

| ≥30 | 54 | 53 | 83 | 32 | ||

| Ethnicity | White | 105 | 87 | 156 | 64 | 0.085 |

| Spanish/Hispanic | 15 | 15 | 15 | 9 | ||

| African American | 14 | 10 | 14 | 4 | ||

| Other | 5 | 10 | 3 | 1 | ||

| Menopausal status | Post | 83 | 64 | 100 | 41 | 0.604 |

| Pre | 55 | 56 | 85 | 37 | ||

| Tumor factors | ||||||

| Clinical N classification | N0 | 24 | 16 | 31 | 12 | 0.196 |

| N1 | 56 | 57 | 103 | 36 | ||

| N2 | 14 | 10 | 20 | 7 | ||

| N3 | 40 | 39 | 33 | 22 | ||

| Nuclear grade | I/II | 11 | 14 | 63 | 16 | <0.0001 |

| III | 124 | 98 | 115 | 56 | ||

| Lymphatic invasion | Negative | 46 | 55 | 64 | 25 | 0.131 |

| Positive | 90 | 64 | 121 | 48 | ||

| Vascular invasion | Negative | 58 | 70 | 77 | 30 | 0.012 |

| Positive | 77 | 48 | 107 | 43 | ||

| Treatment factors | ||||||

| Neoadjuvant regimen | A | 30 | 11 | 34 | 16 | |

| A+T | 102 | 32 | 144 | 26 | ||

| A + T + H | NA | 50 | 2 | 23 | ||

| H | NA | 1 | NA | 0 | ||

| T | 6 | 1 | 6 | 2 | ||

| T + H | NA | 26 | NA | 10 | ||

| Other | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Neoadjuvant trastuzumab | No | NA | 45 | NA | 44 | |

| Yes | NA | 77 | NA | 33 | ||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | No | 84 | 58 | 112 | 24 | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 54 | 64 | 76 | 54 | ||

| Neoadjuvant radiotherapy | No | 132 | 122 | 182 | 78 | 0.025 |

| Yes | 7 | 0 | 6 | 0 | ||

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | No | 36 | 14 | 25 | 13 | 0.005 |

| Yes | 102 | 108 | 163 | 65 | ||

| Adjuvant hormonal therapy | No | 135 | 115 | 47 | 26 | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 3 | 6 | 140 | 52 | ||

| Treatment response | ||||||

| Neoadjuvant therapy clinical response | CR | 12 | 25 | 9 | 9 | 0.003 |

| PD | 8 | 2 | 5 | 2 | ||

| PR | 66 | 54 | 102 | 37 | ||

| SD | 48 | 37 | 67 | 25 | ||

| Neoadjuvant therapy pathological response | pCR | 17 | 37 | 14 | 11 | <0.0001 |

| Non-pCR | 120 | 84 | 173 | 62 | ||

pCR rate among different IBC subgroups

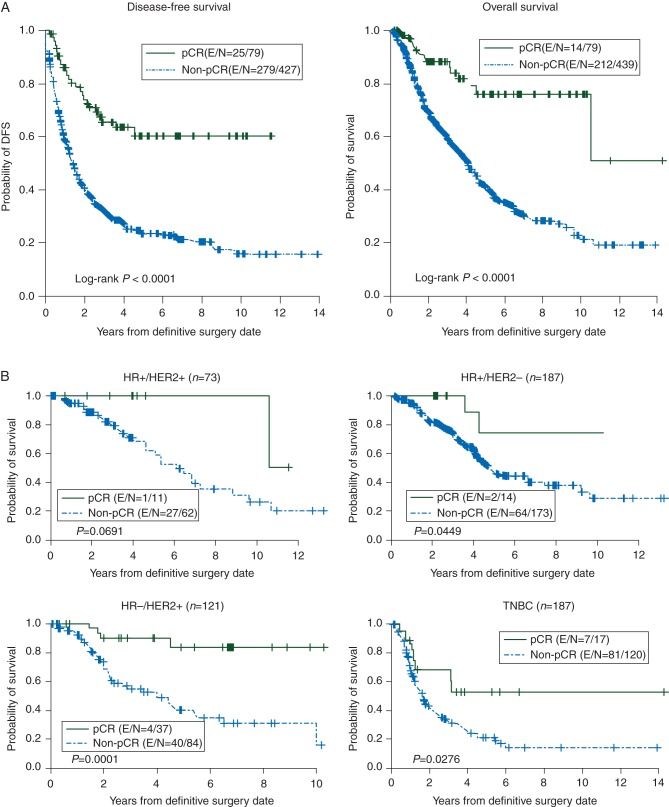

The pCR rate was 15.2% for all 527 patients combined. The rates significantly differed by subtype. The HR-negative/HER2-positive subtype had the highest pCR rate of 30.5% (33.0% for patients who had trastuzumab-based therapy and 14.6% for patients who had non-trastuzumab therapy). The pCR rates were 15.0%, 7.4%, and 12.4% for the HR-positive/HER2-positive, HR-positive/HER2-negative, and TNBC subtypes, respectively. Achieving pCR was a highly favorable prognostic factor in our cohort (Figure 2); we also determined the relationship between pCR and clinical outcome by subtype (Figure 3); except the HR-positive/HER2-positive subtype, achieving pCR was a favorable prognostic factor. It also suggested that the value of pCR might be different in each subtype.

Figure 2.

(A) Survival by whether pCR was achieved. Kaplan–Meier estimates for patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, underwent definitive surgery, and had evaluable status for ER, PR, and HER2. (B) Overall survival for each HR/HER2 subtype by whether pCR was achieved. Kaplan–Meier estimates for patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, underwent definitive surgery, and had evaluable status for ER, PR, and HER2.

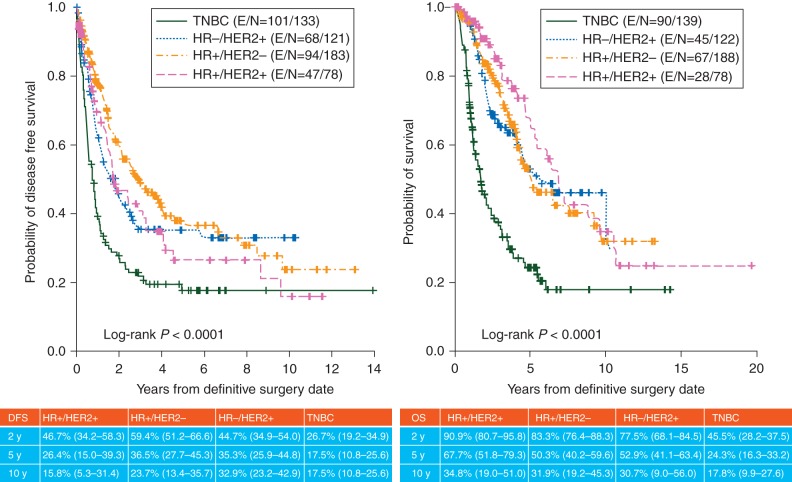

Figure 3.

DFS (left) and OS (right) for each HR/HER2 subtype Kaplan–Meier estimates for patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, underwent definitive surgery, and had evaluable status for ER, PR, and HER2 with respect to OS and DFS in each subtype.

survival analysis by subtype

Figure 4 shows Kaplan–Meier curves for DFS and OS for each subtype. Among the 527 patients, the median follow-up was 38.4 months. The median time to death from diagnosis was 61.2 months (95% CI, 54–69.6 months). The TNBC subtype showed significantly worse prognosis compared with the other subtypes (P < 0.0001). Interestingly, the four subtypes could be separated into two groups with regard to outcome: TNBC and the other three subtypes. In IBC, there was no significant difference in clinical outcomes between HR-positive/HER2-positive, HR-positive/HER2-negative, and HR-negative/HER2-positive subtypes. In other words, unlike in non-IBCs, in IBC HR-positive status was not associated with favorable prognosis.

We applied both univariate and multicovariate (supplementary Table S1A, available at Annals of Oncology online) Cox proportional hazard models to assess the effect of covariates of interest on OS and DFS; the results showed that pCR, adjuvant hormonal therapy, adjuvant radiotherapy, a lack of vascular invasion, and non-TNBC were associated with longer OS and DFS.

effect of anti-hormonal and anti-HER2-targeted therapy

We analyzed the effect of hormonal therapy in HR-positive disease and of HER2-targeting therapy in HER2-positive disease. For HR-positive disease, 72% of patients received adjuvant hormonal therapy, and having received hormonal therapy was associated with longer DFS and OS (supplementary Figure S1A, available at Annals of Oncology online). In the HR-positive/HER2-positive subtype, however, having had hormonal therapy was not associated with longer OS (supplementary Figure S1B, available at Annals of Oncology online). For HER2-positive disease, 55% of the 200 patients received trastuzumab in clinical trials as part of their neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and 64.5% received trastuzumab in the neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant settings. Having had trastuzumab was not associated with longer OS or DFS in HER2-positive disease overall (supplementary Figure S2A, available at Annals of Oncology online) or when patients with HER2-positive disease were divided by HR status (supplementary Figure S2B, available at Annals of Oncology online).

discussion

Our dataset, the largest to date from a single institution, revealed that primary IBC has a poor prognosis regardless of the HR/HER2 subtype, with the worst outcome in patients with triple-negative IBC. Interestingly, we found that HR-positive disease, irrespective of HER2 status, had poor prognosis that did not differ in terms of OS and DFS from that of the HR-negative/HER2-positive subtype. The overall pCR rate for the 527-patient population was 15.2%.

Hormonal therapy was associated with longer DFS for patients with HR-positive disease, regardless of HER2 status; however, OS was improved by hormonal therapy only if HER2 was negative. Thus, we can argue that hormonal therapy alone may not be a sufficient treatment in the HR-positive/HER2-positive subtype. The HER2-targeting agent trastuzumab improved the pCR rate; however, in our study, the efficacy of anti-HER2 therapy in terms of prolonging OS and DFS did not reach statistical significance. Panades et al. [8] and Gonzalez-Angulo et al. [6] have studied the outcome of IBC management over a period of 40 years; however, so far, the results have failed to show any improvement in survival. In one prospective study, a secondary analysis of the GeparTrio trial, which focused on locally advanced breast cancer and IBC, Costa et al. [9] reported that the pCR rate in IBC was 8.3% even though this trial used the intensified TAC regimen (docetaxel [Taxotere; sanofi-aventis, Berlin, Germany] 75 mg/m2, doxorubicin [50 mg/m2], and cyclophosphamide [500 mg/m2]). These results suggest that advances in chemotherapy and multidisciplinary treatments are still lacking for IBC patients. We must improve preoperative chemotherapy to achieve pCR and thereby enable surgery for IBC patients.

Triple-negative IBC was strongly associated with poor prognosis, which is consistent with other reports from both IBC and non-IBC populations [6, 10, 11]. In triple-negative IBC, most recurrences occurred within the first 2 years, and 5- and 10-year DFS rates were the same, suggesting that delayed recurrences are rare in triple-negative IBC. This finding highlights the need for more effective neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment of this group of patients.

In early breast cancer, ER positivity is clearly an independent prognostic factor for good clinical outcome [12]. A few studies have determined a survival difference among molecular subtypes in locally advanced breast cancer [13, 14]. Sorlie et al. [14] reported on prognosis by intrinsic subtype. The basal-like and HER2-enriched subtypes showed the poorest prognosis, with both shorter time to progression and shorter OS. Patients with the luminal A subtype had a considerably better prognosis compared with those of all other groups. Patients with the luminal B subtype had an intermediate outcome. Thus, results in locally advanced breast cancer are so far similar to those of early breast cancer. Many parameters have been explored in relation to breast cancer biology and outcome, with the general consensus that patients with tumors expressing ER have a relatively favorable prognosis. Interestingly, however, our study showed that HR-positive groups, irrespective of HER2 status, had poor prognosis that did not differ from that of the HR-negative/HER2-positive subgroup.

Locally advanced breast cancer is a heterogeneous category composed of patients with diverse biological processes as well as prognoses. Slowly progressing disease in an elderly woman whose cancer has become inoperable after years without detection is usually more biologically responsive than a rapidly growing, aggressive tumor in a younger woman. Biologically indolent tumors are usually characterized by high ER and PR expression levels, low tumor grade, and a low proliferative index and would more likely show favorable response to hormonal treatment. Unfortunately, in IBC, biologically indolent tumors are not common even among the HR-positive group. In fact, the luminal subtypes are the most heterogeneous with regard to biology and outcome [13, 14]. We believe that this heterogeneity could also be related to the unfavorable prognosis we observed in IBC patients with HR-positive tumors.

The pCR rate also differed for each subtype in our study. Although the sample size was small, results showed that pCR was associated with longer OS in the HR-positive/HER2-negative, HR-negative/HER2-positive, and TNBC subgroups, but not the HR-positive/HER2-positive subtype. When we analyzed ER and HER2 status, pCR was associated with longer OS only in the ER-negative/HER2-positive and TNBC subtypes (data not shown). This was consistent with the report by von Minckwitz et al. [15] that suggested that pCR can be a suitable surrogate end point for patients with luminal B/HER2-negative, HER2-positive, and TNBC disease, but not for those with luminal A and luminal B/HER2-positive tumors. However, a recent meta-analysis of neoadjuvant trials conducted by the FDA was unable to confirm this.

Our study is the first to investigate IBC by subtypes based on not only hormonal status but also HER2 status in a large number of patients from one institution. However, several limitations should be noted. Although the overall sample size was large, the number of patients per subtype was not sufficient for analysis, resulting in limited statistical power. Furthermore, this study has inherent limitations due to its retrospective nature; the treatment histories were varied, and the collected information was not complete. Last, the data originated from a single institution, one that specializes in IBC; therefore, one cannot exclude the possibility of introduction of bias. Finally, interpreting trends over time is problematic, especially with the advent of targeted therapy available to the most recent generation.

In summary, our retrospective study showed that previously known breast cancer subtypes have limited predictive and prognostic power in IBC. After closely examining HR and HER2 status as well as treatment information for our IBC population, we concluded that the TNBC subtype has the worst clinical outcome compared with other subtypes, and currently available treatments are unlikely to improve clinical outcomes of IBC patients. Although the non-TNBC group had better outcomes than did triple-negative IBC, the fact remains that for IBC, targeted therapies such as hormonal therapies and anti-HER2 therapy do not appear as effective as expected in terms of improving clinical outcomes of their targeted populations. The results confirmed that we need novel IBC-specific treatment strategies for all molecular subtypes. A multicenter prospective study is warranted for each subtype of IBC with novel targeted therapies to improve these very poor outcomes.

funding

This work was supported by the Morgan Welch Inflammatory Breast Cancer Research Program and Clinic and a State of Texas Rare and Aggressive Breast Cancer Research Program Grant (to N.T.U.). This research is also supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson's Cancer Center Support Grant (grant number CA016672).

disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

We thank Sunita Patterson for editing assistance.

references

- 1.Dawood S, Merajver SD, Viens P, et al. International expert panel on inflammatory breast cancer: consensus statement for standardized diagnosis and treatment. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:515–523. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hance KW, Anderson WF, Devesa SS, et al. Trends in inflammatory breast carcinoma incidence and survival: the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program at the National Cancer Institute. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:966–975. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schlichting JA, Soliman AS, Schairer C, et al. Inflammatory and non-inflammatory breast cancer survival by socioeconomic position in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, 1990–2008. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134:1257–1268. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2133-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dawood S, Ueno NT, Valero V, et al. Differences in survival among women with stage III inflammatory and noninflammatory locally advanced breast cancer appear early: a large population-based study. Cancer. 2011;117:1819–1826. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Allen PK, et al. Triple-negative subtype predicts poor overall survival and high locoregional relapse in inflammatory breast cancer. Oncologist. 2011;16:1675–1683. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Hennessy BT, Broglio K, et al. Trends for inflammatory breast cancer: is survival improving? Oncologist. 2007;12:904–912. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-8-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bear HD, Anderson S, Brown A, et al. The effect on tumor response of adding sequential preoperative docetaxel to preoperative doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide: preliminary results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Protocol B-27. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4165–4174. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panades M, Olivotto IA, Speers CH, et al. Evolving treatment strategies for inflammatory breast cancer: a population-based survival analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1941–1950. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costa SD, Loibl S, Kaufmann M, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy shows similar response in patients with inflammatory or locally advanced breast cancer when compared with operable breast cancer: a secondary analysis of the GeparTrio trial data. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:83–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.5101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parker JS, Mullins M, Cheang MC, et al. Supervised risk predictor of breast cancer based on intrinsic subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1160–1167. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carey LA, Dees EC, Sawyer L, et al. The triple negative paradox: primary tumor chemosensitivity of breast cancer subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2329–2334. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knight WA, Livingston RB, Gregory EJ, et al. Estrogen receptor as an independent prognostic factor for early recurrence in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1977;37:4669–4671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huber KE, Carey LA, Wazer DE. Breast cancer molecular subtypes in patients with locally advanced disease: impact on prognosis, patterns of recurrence, and response to therapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2009;19:204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sorlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10869–10874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Minckwitz G, Untch M, Blohmer JU, et al. Definition and impact of pathologic complete response on prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in various intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1796–1804. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.