SUMMARY

Priapism is a persistent penile erection that is unrelated to sexual stimulation. The condition may be divided into ischemic and non-ischemic subtypes. Ischemic priapism, the most common variant of the disorder, is typically accompanied with pain and the potential for penile end-organ damage. An erection duration of 4 hours or more is oftentimes quoted as diagnostic of priapism.

The initial management of non-ischemic priapism should be conservative. Prompt attention is indicated in cases of ischemic priapism; the initial management of choice is corporal aspiration with injection of sympathomimetic agents. If medical management fails, a cavernosal shunt procedure is indicated. At our institution, we favor the T-shunt with or without tunneling for the management of refractory ischemic priapism. Stuttering (recurrent) ischemic priapism challenges the clinician to develop a management strategy to prevent future episodes of priapism. Daily treatment with low dose Phosphodiesterase Type 5 Inhibitors is a promising but investigational means of preventing stuttering priapism. This review will focus on new directions and our own experience in the treatment of priapism.

Keywords: Priapism, ischemic priapism, nonischemic priapism, penis, erection

INTRODUCTION

The term “priapism” is derived from Priapus, an ancient Grecian deity of fertility and gardens who was famed for his massive phallus.1 The first report of priapism in the medical literature was by Petraens in 1616.2

Priapism is defined as a penile erection that persists four or more hours and is unrelated to sexual stimulation.3 Priapism may affect males at any age. The condition may be subdivided into a non-ischemic variant (almost universally associated with trauma, typically not painful, and not a medical emergency) and a much more common ischemic variant (typically painful and in need of emergent clinical management). Stuttering (or recurrent) priapism is a variant of ischemic priapism which is distinguished by its’ recurrent nature.

ISCHEMIC PRIAPISM

Definition

Ischemic priapism (formerly known as “low-flow” or “veno-occlusive” priapism) is defined as a prolonged, painful penile erection which prohibits fresh blood from entering the corporal bodies and thus leads to ischemia. Ischemic priapism typically involves the paired corporal bodies but not the corpus spongiosum or glans penis. Because of this, the glans penis is typically not engorged in ischemic priapism.

Ischemic priapism is a compartment syndrome of the penis and may lead to end-organ damage and ED. It may occur due to 1) obstruction of blood flow out of the penis through penile veins and/or 2) failure of the smooth muscle within the spongy erectile tissue of the penis to contract normally. Stuttering priapism is a term utilized to describe ischemic priapism that is recurrent.

Epidemiology

An overall incidence of 1.5 cases of ischemic priapism per 100,000 person-years was reported in the general population of the Netherlands during the years from 1995 to 1999.4 Interestingly, the incidence was higher (2.9 per 100,000 person-years) in men 40 years of age and older.4 A likely rationale for this finding is increased use of intra-cavernosal pharmacotherapy (ICP) for erectile dysfunction (ED) in the older population.5 Indeed, when ICP was excluded as a cause of ischemic priapism the rate was 0.9 cases per 100,000 person-years.4 Sickle cell disease (SCD) is another major risk factor for ischemic priapism; the lifetime probability for development of priapism in men with sickle cell disease is between 29% and 42%.6, 7 Unfortunately, there is evidence to suggest that awareness of priapism is relatively low in men with sickle cell disease; in one study just 5 % of men with sickle cell disease recalled learning that priapism was a potential complication.8 It may be hypothesized that if a group at high risk of priapism is frequently not familiar with the condition that the general public also has a poor understanding of the disorder, although the advent of direct to consumer advertising for erectogenic medications may be changing this in some nations.

Delay in presentation is a serious consequence of public misunderstanding regarding the potential seriousness of a prolonged penile erection. Lack of prompt treatment may have serious repercussions with respect to long-term maintenance of erectile capacity. Prolonged ischemia and acidosis can lead to trabecular interstitial edema, cellular death, corporeal fibrosis, erectile dysfunction and, in extreme cases, penile necrosis.6,9 Therefore, increased patient education and public awareness regarding this condition are mandated.

Pathophysiology

Box 1 summarizes reported etiologies for ischemic priapism; while some of these are well-established risk factors, others have been reported only as single case reports. Unfortunately, it is estimated that around half of ischemic priapism cases are idiopathic.9

Box 1 Etiology of priapism.

| Idiopathic |

Hematologic dyscrasia

|

| Drug |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nonhematologic malignant neoplasms (primary or metastatic)

|

Neurologic conditions

|

Trauma

|

A). Hematological Hyperviscosity

Trapping of deformed, hyperviscous red blood cells in the erectile bodies and veins that drain them was thought to be the leading cause of ischemic priapism for many years. This proposed mechanism has come under closer scrutiny in recent years but there is no disagreement that blood dyscrasias (such as SCD, thalassemia, leukemia, hemoglobin Hb Olmsted, thrombophilia, and multiple myeloma) increase the risk of ischemic priapism.10–13 SCD is the leading hematologic cause of ischemic priapism, accounting for approximately 23% of adult cases and 63% of pediatric cases.14 Because the sickle cell trait is more common in people of African descent, Africans and African-Americans may have higher rates of priapism than other racial groups. Increased blood viscosity has also been associated with some forms of parenteral hyperalimentation, hemodialysis and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency; it is by this mechanism that these conditions are thought to precipitate priapism on rare occations.15–17

B). Nonhematologic malignant neoplasms

Men with advanced cancers of the pelvic organs may develop priapism due to tumor infiltration of the veins draining the penis. Cancers of the penis, urethra, bladder, prostate, kidney and rectum have been linked to priapism.18–23

C). Drugs

The smooth musculature of the cavernous arteries and corporal bodies are designed to relax and dilate during sexual stimulation to permit enhanced blood flow to the penis. With engorgement, veins that drain the penis are compressed and blood becomes trapped in the corporal bodies. When sexual arousal has passed the cavernosal smooth muscle contracts. This leads to opening of venous outflow channels and the restoration of blood flow out of the penis. A number of drugs may impair the ability of cavernosal smooth muscles to contract, potentially leading to ischemic priapism (see box 1).

D). Neurologic conditions

Neurologic infections such as syphilis, cerebrovascular accidents, brain tumors, epilepsy, intoxication, brain or spinal cord injuries, lumbar disk herniation or stenosis, cauda equine syndrome, and regional or general anesthesia have been linked with priapism.43–49 This type of neurologically driven priapism is thought to be secondary to nervous dysregulation.50

NON-ISCHEMIC PRIAPISM

Also known as “high flow” or “arterial” priapism, this is a rare condition in which there is unregulated arterial inflow of blood into the corpora cavernosa due to rupture of a branch of the cavernosal artery. This rupture is almost universally the result of penile, perineal or pelvic trauma; it has also been associated with iatrogenic trauma.

In non-ischemic priapism, the penis is enlarged and firm compared to its’ baseline flaccid state, but it is usually not as rigid as it would be with normal sexual arousal. Non-ischemic priapism is typically not painful; therefore, these patients tend to seek medical attention much later than those with ischemic priapism (upwards of 3 years after onset has been reported).51

Epidemiology

To our knowledge the first report of non-ischemic priapism in the medical literature was in 1960.52, 53 There are few data on the epidemiology of this disorder but it is much rarer than ischemic priapism.

Pathophysiology

Non-ischemic priapism occurs secondary to unregulated inflow of blood from an arterial source into the corporal bodies. It is differentiated from ischemic priapism in that the increased inflow does not lead to complete engorgement and obstruction of the venous outflow channels; for this reason pain and ischemia do not develop. The most common cause of this condition is thought to be injury to a penile artery with subsequent delayed fistula formation into the corpus cavernosum.54–55 It is our hypothesis that arterial weakening associated with trauma may not produce a fistula immediately but subsequent penile erection (during sexual or nocturnal erections) may increase cavernous artery pressure to a point that rupture occurs.

Traumatic injury to the penis, scrotum, or perineum is by far the most common etiology for non-ischemic priapism. Non-ischemic priapism has been reported as a complication of medical and surgical management of ischemic priapism.56–58 Other surgical procedures associated with non-ischemic priapism include cold-knife internal urethrotomy for urethral stenosis,59 hydraulic erection during Nesbit corporoplasty,60 deep dorsal vein arterialization for vasculogenic impotence,61 and self-administered ICP for ED.62

Although trauma accounts for the vast majority of cases of non-ischemic priapism, several other mechanisms have been reported including testosterone supplementation in boys,63 SCD,64,65 Acute Lymphatic Leukemia,66 Fabry’s disease (a condition of abnormal lipid deposition in blood vessels),67 corporal metastases,68 and paraneoplastic syndromes.44 The pathogenesis of blood dyscrasia associated non-ischemic priapism may theoretically be a variant of ischemic priapism in which venous outflow is not completely compromised. Fabry’s associated non-ischemic priapism is thought to be secondary to endothelial and/or autonomic ganglia dysfunction. Metastatic deposits may alter corporal blood flow such that a fistulous connection develops.

EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT OF PROLONGED PENILE ERECTION

The evaluation of the patient with a prolonged penile erection has four components: history, physical examination, laboratory testing and imaging studies.

Patient history and physical examination

The first and most important step is to determine whether the condition is ischemic or non-ischemic priapism. Ischemic priapism is suspected when the patient has penile pain, has used a medicine known to be associated with ischemic priapism, has SCD or another blood abnormality, and/or when physical exam reveals a fully rigid penile shaft.3

Non-ischemic priapism is suspected when there is no or minimal pain, a history of trauma or surgery, and physical exam reveals a penis that is merely engorged or partially erect.3

Laboratory Tests

A complete blood count and sickle cell prep should be obtained to rule out abnormalities of red and white cells as well as platelets. Urine toxicology may be performed if use of illicit drugs is suspected. A corporal blood specimen may be aspirated to assess corporal oxygen tension and acidity. Blood aspirated from a patient with ischemic priapism is has been described as “crankcase oil-like,” due to its’ darkness and viscosity, whereas specimens from patients with non-ischemic priapism are typically similar to arterial blood.3 Table 1 summarizes the typical blood gas value. It is important to remember that all cases of priapism begin with influx of arterial blood and as such cavernous blood gases analysis, if done early, may be misleading.

Table 1.

Typical cavernosal blood gases values.

| Source | pH | Po2 (mm-Hg) | Pco2 (mm-Hg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemic priapism | < 7.25 | < 30 | > 60 |

| Non-ischemic priapism | > 7.30 | > 50 | < 40 |

| Normal arterial blood | 7.40 | > 90 | < 40 |

Imaging studies

Color duplex ultrasound examination of the penis and perineum is the imaging test of choice to assess corporal blood flow throughout the length of the corporal bodies. Patients with ischemic priapism have no blood flow in the cavernosal arteries. Patients with non-ischemic priapism have normal to high blood flow in the cavernosal arteries; arterial fistulae or pseudoaneurysms may also be noted (Figure 1). The use of Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA),69 contrast enhanced computed tomography,70 and nuclear medicine scans71 for the evaluation of priapism has been reported but these tests should not be considered standard of care.

Figure 1.

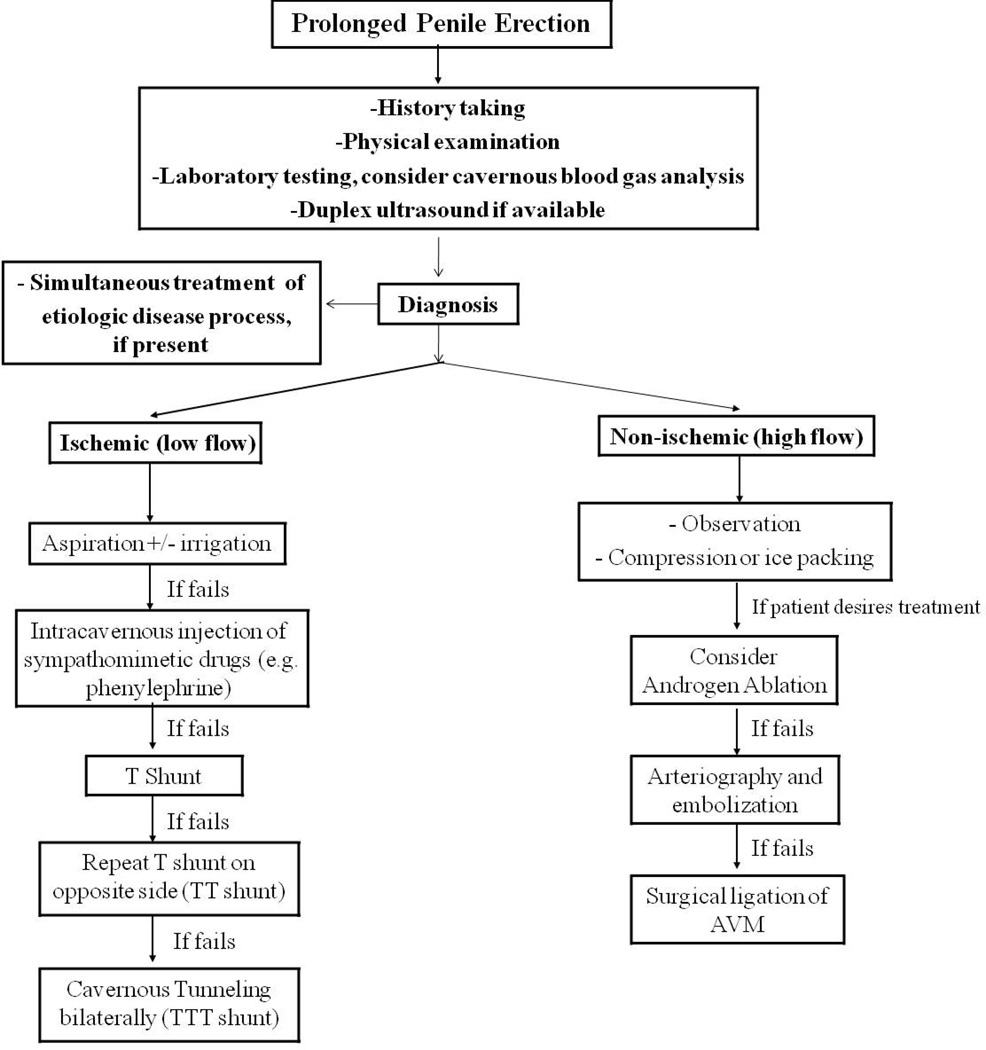

Management algorithm for priapism

Arteriography may be utilized to precisely localized arterial fistulae in non-ischemic priapism; typically this is only undertaken in the context of attempted treatment with super-selective embolization of affected vessel.72

TREATMENT

A management algorithm for prolonged penile erection is presented in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Color duplex ultrasound image of non-ischemic priapism following a straddle injury; shown is a ruptured branch of the cavernous artery pumping blood to a cystic cavity within the corpus cavernosum. Note the jet of arterial blood (yellow).

Treatment of Ischemic priapism

Ischemic priapism is a medical emergency. Time is of the essence and better results can be expected when treatment is started quickly. Restoration of cavernous blood flow and prevention of end-organ damage is the primary goal in the management of ischemic priapism; even after successful treatment some degree of penile edema and enlargement may persist for several hours or days.3

If available, prompt therapy for the root cause of ischemic priapism is indicated. Intravenous fluids, pain medications, alkalization and supplemental oxygen have been the traditional treatments of choice for men with priapism associated with sickle cell disease. Exchange blood transfusion has also been commonly used to treat sickle cell associated ischemic priapism, although recent research has cast some doubt on whether this is an effective treatment.73 In the case of priapism from advanced pelvic cancer, treatment with radiation or chemotherapy may be helpful.18 Treatment of underlying conditions should not delay treatment that is intended specifically to reverse penile erection.

Medical treatments for ischemic priapism

Oral systemic therapy (such as terbutaline or pseudoephedrine) has been reported to be superior to placebo in the management of ICP induced ischemic priapism but clinical efficacy for these treatments is just 28–36%.74 This type of treatment should not be seen as standard of care but may be considered as an adjunct treatment prior to more advanced urological intervention.

Corporal aspiration is a simple intervention that often produces softening of the erect penis and relief of pain, with a success rate around 30%.3 During aspiration, a butterfly needle (19 or 21 gauge) is inserted into either the head or shaft of the penis and blood is aspirated. Typically a “penile block” of local anesthetic is administered before this treatment to minimize patient discomfort. While corporal aspiration is an important intervention, in most cases this procedure is insufficient by itself to completely reverse the process of ischemic priapism.36

Intra-cavernous injection of sympathomimetic drugs (such as ephedrine, epinephrine, norepinephrine, metaraminol and phenylephrine) is the standard of care in the treatment of ischemic priapism.75 Phenylephrine, an alpha-1-selective adrenergic agonist without beta-mediated inotropic and chronotropic cardiac effects, is the agent of choice due to its’ safety profile.3,76 The medication is typically administered at a dose of 0.1–0.5 mg in 1 mL of sterile saline; dose may be adjusted based on clinical concern regarding the potential hemodynamic response of the patient to sympathomimetic treatment. Treatment may be repeated over the course of 3 to 5 minutes interval until the penis is notably detumesced.

Close monitoring for dizziness, headache, acute hypertension, reflex bradycardia, tachycardia, palpitation, and cardiac arrhythmia are recommended for patients undergoing sympathomimetic treatment for ischemic priapism. Serial measurement of blood pressure and cardiac monitoring should be considered for patients with high blood pressure or heart disease.36

The success rate of intra-cavernous injection of sympathomimetic drugs with or without irrigation is reported between 43% to 81%.3 One study describes almost 100% success if the procedure is done within 12 hours of onset.77Declines in the efficacy of the treatment in ischemic priapism of long duration is likely due to impaired smooth muscle response to sympathomimetics after extended periods of hypoxia and acidosis.78

Surgical treatments for ischemic priapism

Surgical intervention for ischemic priapism is indicated when repeated sympathomimetic injections have failed (if no results are seen within 1 hour). Surgery for ischemic priapism consists exclusively of shunt procedures to alleviate corporal compartment syndrome and penile pain. While all shunts carry the risk of erectile dysfunction, it is unclear how much of incident ED after ischemic priapism that is managed with shunting is secondary to the disease process and how much is attributable to the shunt itself.

Distal shunts

Cavernoglandular shunt is the first line surgical treatment for refractory ischemic priapism. These procedures create a connection between one or both of the corpora cavernosa and the glans. These shunts may be created by passing a large biopsy needle or 11 blade scalpel through the glans into the corpora cavernosa (the Winters and Ebbehoj shunts, respectively), or via transglanular anastomosis of the cavernosa to the glanular spongiosum (Al-Ghorab). Success rates for distal shunts are reported to range from 66–74% with a 25% incident rate of ED after treatment.3

Proximal shunts

A proximal cavernospongiosal shunt may be created via a perineal incision through which the proximal corporal bodies are anastomosed to the proximal corpus spongiosum. This is known as the Quackels procedure. Reported success rates with the Quackels procedure is 77% with an incident rate of ED of 50%.3

Venous Shunts

The cavernosaphenous shunts are made between the corpora cavernosa and the saphenous vein (Grayhack procedure), or the superficial or deep dorsal vein of the penis (Barry procedure). Reported success rates with these procedures is around 76% with incident in ED in about 50% of cases.3

Novel Procedures for Ischemic Priapism

Recently, Kilinc described a new temporary artificial cavernosal-cephalic shunt for ischemic priapism in 15 patients with ischemic priapism of 20 hours mean duration. For this procedure two 18 gauge angiocaths were placed into the corporal bodies (one for each corpus) via a translganular approach. One angiocath was infused with a heparinized sterile saline solution and the other was connected to a third 18 gauge angiocath placed in the cephalic vein of the arm. By this means a continuous corporal to systemic circulation shunt was created. Irrigation was maintained for 30 minutes and then resumed if detumescence had not occurred; this was repeated as needed until the penis became flaccid or 6 hours had past. The complete detumescence rate was 87% (13/15) with a mean treatment duration of 110 minutes (range 30 to 300 minutes); the two patients that did not respond were successfully managed with Grayhack-type shunts. Of the patients in whom detumescence was achieved, eight manifested ED (seven were screened with subjective assessment of “mild to severe ED,” and 5 were evaluated with the IIEF-EF, one of whom met criteria for ED).79 This approach is interesting although concerns about the potential for microemboli or other complications of extracorporal shunting exist. It may also be argued that the procedure is not a true shunt but rather a semi-automated means of corporal irrigation.

At our institution, we favor the T-shunt for ischemic priapism refractory to intra-cavernous alpha-adrenergic agent injection. The T-shunt is created by passing a 10 blade scalpel through the head of the penis into the ipsilateral corpora cavernosa after a local anesthetic is administered. The blade is inserted until the hub contacts the glans and then rotated 90 degrees to ensure creation of a large fistula (Figure 3). The scalpel is then withdrawn and the penis “milked” to express venous blood. If it is not possible to “indent” the corporal bodies with gentle pressure after 10–15 minutes priapism may be persistent and the procedure may be repeated on the contralateral side (the TT shunt). If the corporal bodies remain rigid even after TT shunt corporal (as may occur in priapism of more than 3 days duration) tunneling may be performed by passage of a 20–24 F urethral sound or dilator through the glanular incisions to restore proximal to distal circulation (the TTT shunt, Figure 4). TTT shunt may be required in cases of prolonged ischemic priapism where tissue edema prohibits proximal to distal circulation.80 These procedures are routinely performed in our clinic or the emergency room with high success rates with respect to pain resolution. The theoretical advantage of this approach is that the shunt may be enlarged so as to include both distal and proximal portions of the corpora, thus permitting better drainage of the entire cavernous body (figure 5). Publication of our long term results with respect to erectile function is in process.

Figure 3.

Unilateral T shunt. The scalpel is inserted into the cavernous body using a transglanular approach subsequently rotated 90 degrees away from the urethra.

Figure 4.

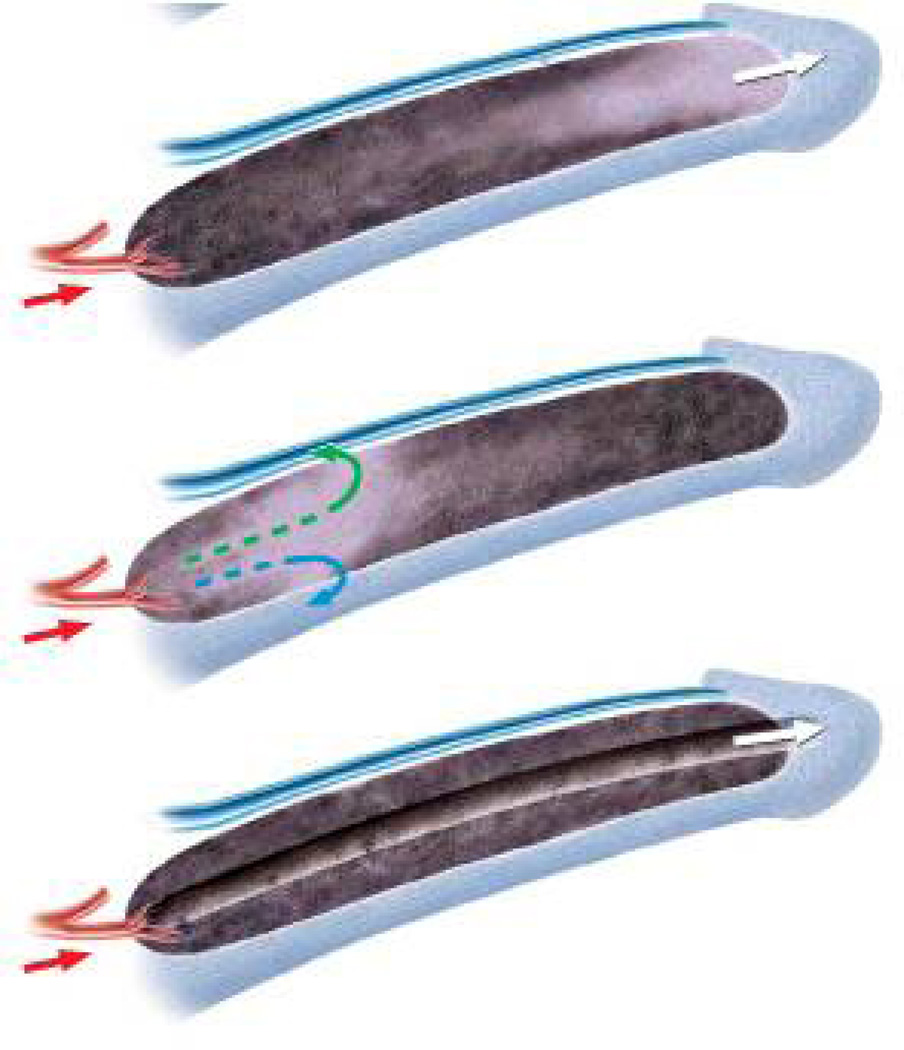

TTT shunt. If bilateral T shunt fails to relieve ischemic priapism, bilateral cavernosal tunneling may be utilized to enable passage of blood from the proximal to the distal penis and eventually through the shunt.

Figure 5.

In priapism of more than 3 days duration tissue death may lead to severe edema in the corpora cavernosa: Distal shunts (first figure) may not drain the proximal corpora. Similarly, proximal shunts (second figure) may not drain the distal corpora. The T shunt (third figure) may be modified with corporal tunneling (TTT shunt) so as to produce a tunnel for the blood to flow from proximal to distal penis.

Postoperative care

Pressure should be exerted intermittently on the body of the penis to promote fistula patency. Tight compressive dressings may compromise drainage and should be avoided.

Even after successful shunts the penis may appear partially erect due to persistent edema. If any doubt exists, a duplex ultrasound examination should be used to determine whether normal blood flow has resumed or not. Repeat sampling of blood to assess the oxygen content within the penis can be used to assess response to treatment although it should be borne in mind that changes in corporal oxygen tension and pH may not be immediate. Intracavernous pressure measurement may also be utilized to assess response to shunt treatment; an intracavernous pressure of less than 40 mm-Hg indicates a successful procedure. If the pressure is over 40 mm-Hg, additional treatment may be needed.81

Some authors have advocated for immediate placement of penile prostheses in patients with ischemic priapism of long duration due to the difficulty with penile prosthetic placement after corporal fibrosis has occurred.82,83 This option may be discussed with patients but should not be seen as standard of care. If it is undertaken a biopsy of corporal tissue should be obtained to confirm end stage corporal tissue damage.

Management of stuttering priapism

Reliable patients with stuttering priapism may be instructed on the procedure for intracavernous injection with sympathomimetics and provided the medication for home use.36

Antiandrogens or gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues have been utilized to prevent nocturnal penile tumescence and ischemic priapism in men with stuttering priapism. This has been effective in some cases with preservation of erectile function but there are significant risks to prolonged hypogonadism.84, 85 Other medical therapies, such as hydroxyurea, gabapentin, methylene blue, oral baclofen, digoxin, etilephrine, procyclidine and estradiol, have been reported, but the evidence for their clinical use is not robust.86–93

Non-ischemic priapism

Non-ischemic priapism typically does not lead to significant end organ damage and may be managed conservatively. In some cases rest, time, and ice packs have been shown to resolve the condition spontaneously.94 Some men choose to defer therapy and have been reported to live with non-ischemic priapism while maintaining adequate erectile function for years.71,95 Nevertheless, some men are bothered by the condition and desire more immediate treatment.96 Treatment of non-ischemic priapism is geared towards elimination of the cavernous artery fistula.97

Angiography with superselective embolization is the treatment of choice if prompt definitive management of non-ischemic priapism is desired. The first report of successful selective arterial embolization for non-ischemic priapism was by Wear and co-workers.72 Embolization has been performed using gel-foam, coils, autologous blood clot, polyvinyl alcohol, and N-butylcyanoacrylate (NBCA).98–101 Microcoils carry are advantageous with respect to ease of placement and do not carry the risk of dissolution and recurrence of non-ischemic priapism; however, the risk of ED may be greater when these permanent embolic devices are used as opposed to gelfoam or autologous blood. Autologous blood clot is cheap, carries low risk of foreign body reaction and antigenicity, and is a temporary occlusive agent allowing recanalization of the cavernosal artery and restoration of penile blood flow in the fistula segment after healing.102 Success rates of 100% with complete preservation of erectile function have been reported in cases of non-ischemic priapism treated by superselective angioembolization with autologous blood clot, although second embolization sessions may be required.103,104 Some authors have suggested that immediate repeat embolization may not be required in all cases as cavernosal-spongiosal communications may be supplying the fistula after embolization and these communications may spontaneously close.105

Young children have penile arteries of smaller diameter; for this reason, superselective embolization may be more disruptive and should be undertaken with extreme caution in children.106, 107 Embolization also carries the risks of radiation and contrast medium exposure. Color duplex ultrasound can be used for directing the angiographic catheter within the penile arteries, hence minimizing radiation exposure.108, 109

Initial success rates for embolization are approximately 73–89% although repeat procedures may be required. A 20–25% incidence of ED has been reported.98,110–112 This rate is likely to vary dependent on the type of embolus used. Rare reported complications of pudendal artery embolization include penile gangrene, gluteal ischemia, purulent cavernositis, perineal abscess, and migration of embolization material.113

Alternatives for patients who decline superselective embolization include intracavernous methylene blue,114 temporary blockage and thrombus formation created using an ultrasound probe to compress the arteriosinusoidal fistula,115, 116 or ultrasound-guided thrombin injection.117

Cavernosal artery ligation is another option reserved in case of failures of embolization. It can be performed in two ways: by ligating the cavernous artery at the outlet from Alcock’s canal, or by performing an exploratory corporotomy followed by ligation of the arterial fistula.118 Ligation of the cavernous artery carries a substantial risk of worsening erectile function. Selective ligation of the fistula decreases the risk of ED but the presence of a pseudocapsule must be documented prior to surgery using duplex ultrasound; typically it takes 6 months for a capsule to form so fistula ligation should not be contemplated until 6 months after presentation.

In our practice, we have successfully used antiandrogens for the treatment of non-ischemic priapism in four patients with good results. These results will be published in the near future.

New directions in the treatment of priapism

Several recent studies have suggested that daily treatment with low dose inhibitors of the enzyme phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) may be a novel means to treat stuttering priapism. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) knockout mice, which phenotypically display priapism-like activity, have lower levels of PDE5 compared to controls. PDE5 is responsible for breaking down cGMP, the intracellular messenger that promotes vasodilation and penile erection. This may lead to prolonged presence of cGMP and erections of greater duration.119 Inhibitors of PDE5 (PDE5I) have been shown to upregulate expression of PDE5 in myocytes in vitro.120 If PDE5 were upregulated in cavernosal smooth muscle in vivo, it may antagonize priapism.

A pilot study by Burnett et al. reported that chronic administration of a PDE5I to seven patients with stuttering priapism led to marked clinical improvements in six patients while maintaining the capacity for sexual erections.121 Although PDE5I may represent an exciting new means of therapy for priapism, more studies are needed before this treatment should be considered outside of a research setting.

CONCLUSIONS

Ischemic priapism is a urologic emergency requiring prompt recognition and treatment to avoid long-term complications such as ED. Non-ischemic priapism may be managed conservatively although treatment options are available for men who desire resolution of the problem. A number of reliable treatments are available for both ischemic and non-ischemic priapism. Stuttering priapism is a condition which is still not well understood and there is at this time no standardized treatment for this condition. Future work will hopefully help to illuminate the molecular mechanisms of ischemic priapism and improve our ability to care for men with this condition.

REVIEW CRITERIA.

The data for this review was obtained by using the MEDLINE and PubMed database. All searches were restricted to articles written in English and published between 1970 and December 2008. The last search was performed on December 21 2008. The search terms used were “priapism”, “prolonged erection” and “painful erection”. Relevant articles were elected from these searches and the reference lists from the identified articles were searched for further papers. Our own experience of treatments used in our institution was also incorporated.

KEY POINTS.

Non-ischemic priapism is a medical emergency; prompt diagnosis and immediate, direct treatment of priapism is required for optimal outcome

Injection of sympathomimetic agents is the first line treatment of choice in the management of ischemic priapism

If sympathomimetics fail, surgical shunt should be utilized to treat ischemic priapism; we recommend use of the T shaped shunt and its’ variants

Inhibitors of PDE5 may be a novel new means to manage recurrent, stuttering priapism

Conservative management may be adequate for non-ischemic priapism but if therapy is desired superselective embolization or surgical ligation of the fistula tract are viable options

KEY POINTS.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References

- 1.Papadopoulos I, Kelami A. Priapus and priapism from mythology to medicine. Urology. 1988;32:385–386. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(88)90252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hinman F. Priapism. Ann Surg. 1914;60:689–716. doi: 10.1097/00000658-191412000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montague DK, et al. American Urological Association guideline on the management of priapism. J Urol. 2003;70:1318–1324. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000087608.07371.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eland, et al. Incidence of priapism in the general population. Urology. 2001;57:970–972. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)00941-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Earle CM, et al. The incidence and management of priapism in Western Australia: a 16 year audit. Int J Impot Res. 2003;15:272–276. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emond AM, et al. Priapism and impotence in homozygous sickle cell disease. Arch Intern Med. 1980;140:1434–1437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mantadakis E, et al. Prevalence of priapism in children and adolescents with sickle cell anemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1999;21:518–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett N, Mulhall J. Sickle cell disease status and outcomes of African-American men presenting with priapism. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1244–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brant WO, et al. Priapism: etiology, diagnosis and management. AUA update series. 2006;25:99–107. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quigley M, Fawcett DP. Thrombophilia and priapism. BJU Int. 1999;83:155. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thuret I, et al. Priapism following splenectomy in an unstable hemoglobin: Hemoglobin Olmsted beta 141 (H19) Leu -->Arg. Am J Hematol. 1996;51:133–136. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8652(199602)51:2<133::AID-AJH6>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morano SG, et al. Treatment of long-lasting priapism in chronic myeloid leukemia at onset. Ann Hematol. 2000;79:644–645. doi: 10.1007/s002770000199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenbaum EH, et al. Priapism and multiple myeloma. Successful treatment with plasmapheresis. Urology. 1978;12:201–202. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(78)90334-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson JH, Winter CC. Priapism: Evolution of management in 48 patients in a 22-year series. J Urol. 1977;117:455–458. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)58497-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hébuterne X, et al. Priapism in a patient treated with total parenteral nutrition. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1992;16:171–174. doi: 10.1177/0148607192016002171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singhal PC, et al. Priapism and dialysis. Am J Nephrol. 1986;6:358–361. doi: 10.1159/000167190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finley DS. Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency Associated Stuttering Priapism: Report of a Case. J Sex Med. 2008;5:2963–2966. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan PT, et al. Priapism secondary to penile metastasis: A report of two cases and a review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 1998;68:51–59. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199805)68:1<51::aid-jso11>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hettiarachchi JA, et al. Malignant priapism associated with metastatic urethral carcinoma. Urol Int. 2001;66:114–116. doi: 10.1159/000056584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cherrie RJ, Brosman SA. Case profile: priapism secondary to metastatic adenocarcinoma of rectum. Urology. 1985;25:655. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(85)90308-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nezu FM, et al. Malignant priapism as the initial clinical manifestation of metastatic renal cell carcinoma with invasion of both corpora cavernosum and spongiosum. Int J Impot Res. 1998;10:101. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kvarstein B. Bladder cancer complicated with priapism. A case report. Scand J urol nephrol suppl. 1996;179:155–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schroeder-Printzen I, et al. Malignant priapism in a patient with metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. Urol int. 1994;52:52–54. doi: 10.1159/000282571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lue TF. Priapism after transurethral alprostadil. J Urol. 1999;161:725–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wills BK, et al. Sildenafil citrate ingestion and prolonged priapism and tachycardia in a pediatric patient. Clin Toxicol. 2007;45:798–800. doi: 10.1080/15563650701664483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King SH, et al. Tadalafil-associated priapism. Urology. 2005;66:432. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubin SO. Priapism as a probable sequel to medication. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1968;2:81–85. doi: 10.3109/00365596809136974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siegel S, et al. Prazosin-induced priapism. Pathogenic and therapeutic implications. 1988;61:165. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1988.tb05073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sadeghi-Nejad H, Jackson I. New-onset priapism associated with ingestion of terazosin in an otherwise healthy man. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1766–1768. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Avisrror MU, et al. Doxazosin and priapism. J Urol. 2000;163:238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pahuja A, et al. Unresolved priapism secondary to tamsulosin. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17:293–294. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qazi HA, et al. Stuttering priapism after ingestion of alfuzosin. Urology. 2006;68:890.e5–890.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Compton MT, Miller AH. Priapism associated with conventional and atypical antipsychotic medications: A review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:362–366. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kulmala, et al. Aetiology of priapism in 207 patients. Eur Urol. 1995;28:241–245. doi: 10.1159/000475058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saenz de TI, et al. Pathophysiology of prolonged penile erection associated with trazodone use. J Urol. 1991;145:60–64. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38247-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pryor J, et al. Priapism. J Sex Med. 2004;1:116–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2004.10117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DubinN N, Razack AH. Priapism: ecstasy related? Urology. 2000;56:1057. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00839-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin PH, et al. Low molecular weight heparin induced priapism. J Urol. 2004;172:263. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000132155.38285.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salerno TA, et al. Priapism after aortic valve replacement. Can J Surg. 1982;24:202–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harmon JD, et al. Stuttering priapism in a liver transplant patient with toxic levels of FK506. Urology. 1999;54:366. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zargooshi J. Priapism as a complication of high dose testosterone therapy in a man with hypogonadism. J Urol. 2000;163:907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teixeira CE, et al. Nitric oxide release from human corpus cavernosum induced by a purified scorpion toxin. Urology. 2004;63:184–189. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00785-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gallagher JP. A lesson in neurology from the hangman. JSC Med Assoc. 1995;91:38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greschner M, et al. High-flow priapism leading to the diagnosis of lung cancer. Urol Int. 1998;60:126–127. doi: 10.1159/000030227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hopkins A, et al. Erections on walking as a symptom of spinal canal stenosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987;50:1371–1374. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.50.10.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Munro D, et al. The effect of injury to the spinal cord and cauda equina on the sexual potency of men. N Engl J Med. 1948;239:903–911. doi: 10.1056/NEJM194812092392401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ravindran M. Cauda equina compression presenting as spontaneous priapism. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1979;42:280–282. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.42.3.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dittrich A, et al. Treatment of pharmacological priapism with phenylephrine. J Urol. 1991;146:323–324. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37781-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruan X, et al. Priapism--a rare complication following continuous epidural morphine and bupivacaine infusion. Pain Physician. 2007;10:707–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burnett AL. Pathophysiology of priapism: Dysregulatory erection physiology thesis. J Urol. 2003;170:26–34. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000046303.22757.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ilkay AK, et al. Conservative management of high-flow priapism. Urology. 1995;46:419–424. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)80235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burt FB, et al. A new concept in the management of priapism. J Urol. 1960;83:60–61. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)65655-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Witt MA, et al. Traumatic laceration of intracavernosal arteries: The pathophysiology of nonischemic, high flow, arterial priapism. J Urol. 1990;143:129–132. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39889-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Towbin R, et al. Priapism in children: treatment with embolotherapy. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:483–487. doi: 10.1007/s00247-007-0441-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim SH, Kim SH. Post-traumatic erectile dysfunction: Doppler US findings. Abdom Imaging. 2006;12:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00261-005-0217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McMahon CG. High flow priapism due to an arterial-lacunar fistula complicating initial veno-occlusive priapism. Int J Impot Res. 2002;14:195–196. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rodríguez J, et al. High-flow priapism as a complication of a veno-occlusive priapism: two case reports. Int J Impot Res. 2006;18:215–217. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bertolotto M, et al. High-flow priapism complicating ischemic priapism following iatrogenic laceration of the dorsal artery during a Winter procedure. J Clin Ultrasound. 2008;37:61–64. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tuygun C, et al. Post-surgical high-flow priapism treated by embolization. Int J Urol. 2007;14:1107–1108. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liguori G, et al. High-flow priapism (HFP) secondary to Nesbit operation: management by percutaneous embolization and colour Doppler-guided compression. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17:304–306. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wolf JS, Jr, Lue TF. High-flow priapism and glans hypervascularization following deep dorsal vein arterialization for vasculogenic impotence. Urol Int. 1992;49:227–229. doi: 10.1159/000282434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim KR, et al. Treatment of high-flow priapism with superselective transcatheter embolization in 27 patients: a multicenter study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18:1222–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arrigo T, et al. High-flow priapism in testosterone-treated boys with constitutional delay of growth and puberty may occur even when very low doses are used. J Endocrinol Invest. 2005;28:390–391. doi: 10.1007/BF03347210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ramos CE, et al. High flow priapism associated with sickle cell disease. J Urol. 1995;153:1619–1621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Poey C, et al. Non traumatic high flow priapism: arterial embolization treatment. J Radiol. 2006;87:115–119. doi: 10.1016/s0221-0363(06)73981-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mentzel HJ, et al. High-flow priapism in acute lymphatic leukaemia. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:560–563. doi: 10.1007/s00247-003-1124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Foda MM, et al. High-flow priapism associated with Fabry's disease in a child: a case report and review of the literature. Urology. 1996;48:949–952. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(96)00320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dubocq FM, et al. High flow malignant priapism with isolated metastasis to the corpora cavernosa. Urology. 1998;51:324–326. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00607-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.El-Assmy A, et al. Use of magnetic resonance angiography in diagnosis and decision making of post-traumatic, high-flow priapism. Scientific World Journal. 2008;19:176–181. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2008.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Suzuki K, et al. Post-traumatic high flow priapism: demonstrable findings of penile enhanced computed tomography. Int J Urol. 2001;8:648–651. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2001.00391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hakim LS, et al. Evolvong concepts in the diagnosis and treatment of arterial high flow priapism. J Urol. 1996;155:541–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wear JB. A new approach to the treatment of priapism. J Urol. 1977;117:252–254. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)58419-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Merritt AL, et al. Myth: blood transfusion is effective for sickle cell anemia-associated priapism. CJEM. 2006;8:119–122. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500013609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lowe FC, Jarow JP. Placebo-controlled study of oral terbutaline and pseudoephedrine in management of prostaglandin E1-induced prolonged erections. Urology. 1993;42:51–53. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(93)90338-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maan Z, et al. Priapism--a review of the medical management. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2003;4:2271–2277. doi: 10.1517/14656566.4.12.2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Muruve N, Hosking DH. Intracorporeal phenylephrine in the treatment of priapism. J Urol. 1996;155:141–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kulmala RV, et al. Effects of priapism lasting 24 hours or longer caused by intracavernosal injection of vasoactive drugs. Int J Impot Res. 1995;7:131–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Broderick GA, Harkaway R. Pharmacologic erection: time-dependent changes in the corporal environment. Int J Impot Res. 1994;6:9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kilinc M. Temporary cavernosal-cephalic vein shunt in low-flow priapism treatment. Eur Urol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.10.009. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Garcia MM, et al. T-shunt with or without tunnelling for prolonged ischaemic priapism. BJU Int. 2008;102:1754–1764. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bochinski DJ, et al. The treatment of priapism: when and how? Int J Impot Res. 2003;15:S86–S90. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ralph DJ, et al. The Immediate Insertion of a Penile Prosthesis for Acute Ischaemic Priapism. Eur Urol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.09.044. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ree RW, et al. The management of low-flow priapism with immediate insertion of a penile prosthesis. BJU int. 2002;90:893–897. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.03058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Steinberg J, Eyre RC. Management of recurrent priapism with epinephrine self-injection and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue. J Urol. 1995;153:152–153. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199501000-00054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dahm P, et al. Antiandrogens in the treatment of priapism. Urology. 2002;59:138. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01492-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Saad ST, et al. Follow-up of sickle cell disease patients with priapism treated by hydroxyurea. Am J Hematol. 2004;77:45–49. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Perimenis P, et al. Gabapentin in the management of the recurrent, refractory, idiopathic priapism. Int J Impot Res. 2004;16:84–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hübler J, et al. Methylene blue as a means of treatment for priapism caused by intracavernous injection to combat erectile dysfunction. Int Urol Nephrol. 2003;35:519–521. doi: 10.1023/b:urol.0000025617.97048.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rourke KF, et al. Treatment of recurrent idiopathic priapism with oral baclofen. J Urol. 2002;168:2552–2553. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gupta S, et al. A possible mechanism for alteration of human erectile function by digoxin: inhibition of corpus cavernosum sodium/potassium adenoine triphosphatase activity. J Urol. 1998;159:1529–1536. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199805000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Perimenis P, et al. The incidence of pharmacologically induced priapism in the diagnostic and therapeutic management of 685 men with erectile dysfunction. Urol In. 2001;66:27–29. doi: 10.1159/000056558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Muneer A, et al. Stuttering priapism--a review of the therapeutic options. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:1265–1270. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shamloul R, el Nashaar A Idiopathic stuttering priapism treated successfully with low-dose ethinyl estradiol: a single case report. J Sex Med. 2005;2:732–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kumar R, et al. Spontaneous resolution of delayed onset, posttraumatic high-flow priapism. J Postgrad Med. 2006;52:298–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ciampalini S, et al. High-flow priapism: treatment and long-term follow-up. Urology. 2002;59:110–113. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01464-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hatzichristou D, et al. Management strategy for the arterial priapism: therapeutic dilemmas. J Urol. 2002;168:2074–2077. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64299-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cakan M, et al. Is the combination of superselective transcatheter autologous clot embolization and duplex sonography-guided compression therapy useful treatment option for the patients with high-flow priapism? Int J Impot Res. 2006;18:141–145. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liu BX, et al. High-flow priapism: superselective cavernous artery embolization with microcoils. Urology. 2008;72:571–573. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.01.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lloret F, et al. Arterial microcoil embolization in high flow priapism. Radiologia. 2008;50:163–167. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8338(08)71951-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chung E, et al. Post traumatic prepubertal high-flow priapism: a rare occurrence. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24:379–381. doi: 10.1007/s00383-007-1936-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Numan F, et al. Posttraumatic high-flow priapism treated by N-butyl-cyanoacrylate embolisation. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1996;19:278–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hanada E, et al. A case report of posttraumatic arterial high-flow priapism. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2008;54:633–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Numan F, et al. Posttraumatic nonischemic priapism treated with autologous blood clot embolization. J Sex Med. 2008;5:173–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hellstrom WJ, et al. The use of transcatheter superselective embolization to treat high flow priapism (arteriocavernosal fistula) caused by straddle injury. J Urol. 2007;178:1059. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bertolotto M, et al. Color Doppler appearance of penile cavernosal-spongiosal communications in patients with high-flow priapism. Acta Radiol. 2008;49:710–714. doi: 10.1080/02841850802027026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Volgger H, et al. Posttraumatic high-flow priapism in children: noninvasive treatment by color Doppler ultrasound-guided perineal compression. Urology. 2007;70:590.e3–590.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.06.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Resim S, et al. High-flow priapism of unknown etiology in a prepubertal boy. Pediatr Int. 2004;46:492–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.2004.01910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Volkmer BG, et al. High-flow priapism: a combined interventional approach with angiography and colour Doppler. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2002;28:165–169. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(01)00502-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bartsch G, Jr, et al. High-flow priapism: colour-Doppler ultrasound-guided supraselective embolization therapy. World J Urol. 2004;22:368–370. doi: 10.1007/s00345-004-0426-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.O'Sullivan P, et al. Treatment of "high-flow" priapism with superselective transcatheter embolization: a useful alternative to surgery. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2006;29:198–201. doi: 10.1007/s00270-005-0089-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kim KR, et al. Treatment of high-flow priapism with superselective transcatheter embolization in 27 patients: a multicenter study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18:1222–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Savoca G, et al. Sexual function after highly selective emobilization of cavernous artery in patients with high flow priapism: long-term follow up. J Urol. 2004;172:644–647. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000132494.44596.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sandock DS, et al. Perineal abscess after embolization for high-flow priapism. Urology. 1996;48:308–311. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(96)00176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Martínez Portillo FJ, et al. Methylene blue: an effective therapeutic alternative for priapism induced by intracavernous injection of vasoactive agents. Arch Esp Urol. 2002;55:303–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Imamoglu A, et al. An alternative noninvasive approach for the treatment of high-flow priapism in a child: duplex ultrasound-guided compression. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:446–448. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sancak T, Conkbayir I. Post-traumatic high-flow priapism: management by superselective transcatheter autologous clot embolization and duplex sonography-guided compression. J Clin Ultrasound. 2001;29:349–353. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kiss A, et al. Treatment of posttraumatic high-flow priapism in 8-year-old boy with percutaneous ultrasound-guided thrombin injection. Urology. 2007;69:779.e7–779.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Shapiro RH, Berger RE. Post-traumatic priapism treated with selective cavernosal artery ligation. Urology. 1997;49:638–643. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Champion HC, et al. Phosphodiesterase-5A dysregulation in penile erectile tissue is a mechanism of priapism. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:1661–1666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407183102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lin G, et al. Up and down-regulation of phosphodiesterase-5 as related to tachyphylaxis and priapism. J Urol. 2003;2:S15–S18. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000075500.11519.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Burnett AL, et al. Feasibility of the use of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors in a pharmacologic prevention program for recurrent priapism. J Sex Med. 2006;3:1077–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]