Abstract

Defects in endosomal sorting have been implicated in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Endosomal traffic is largely controlled by phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PI3P), a phosphoinositide synthesized primarily by lipid kinase Vps34. Here we show that PI3P is selectively deficient in brain tissue from humans with AD and AD mouse models. Silencing Vps34 causes an enlargement of neuronal endosomes, enhances the amyloidogenic processing of amyloid precursor protein (APP) in these organelles and reduces APP sorting to intraluminal vesicles. This trafficking phenotype is recapitulated by silencing components of the ESCRT pathway, including the PI3P effector Hrs and Tsg101. APP is ubiquitinated, and interfering with this process by targeted mutagenesis alters sorting of APP to the intraluminal vesicles of endosomes and enhances amyloid-beta peptide generation. In addition to establishing PI3P deficiency as a contributing factor in AD, these results clarify the mechanisms of APP trafficking through the endosomal system in normal and pathological states.

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative disorder and is characterized by a progressive decline in cognitive function1–3. Brain regions affected by AD display neuronal loss as well as amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Amyloid plaques largely consist of the amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide, which is released by cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP) by the β-secretase Beta-site APP cleavage enzyme 1 (BACE1) and γ-secretase. Autosomal dominant mutations in the genes encoding APP and presenilins 1 and 2, the proteases of the γ-secretase complex, lead to rare early-onset familial cases of AD (FAD). In contrast, the majority of AD cases occur later in life (i.e., late onset AD or LOAD) with no precise cause, although an allelic variant of the gene encoding apolipoprotein E, ApoE4, has been identified as a major risk factor3. Overall the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying LOAD are poorly understood.

APP traffics through organelles of the biosynthetic, secretory and endolysosomal pathways, and undergoes differential and compartment-specific processing by α-, β-, and γ-secretases1,4. Several converging lines of evidence indicate that the amyloidogenic cleavage of APP occurs predominantly in endosomes4,5. First, the proteolytic activity of BACE1 is optimal at a mildly acidic pH, making the endosomal environment ideal for β-secretase-mediated cleavage of APP6. Second, APP appears to interact with BACE1 primarily in the endocytic pathway4,7–9. Third, reducing the access of APP or BACE1 to endosomes by blocking their internalization via clathrin or the small GTPase Arf6, respectively, decreases the amyloidogenic processing of APP4,9–14. Fourth, β-cleaved COOH-terminal fragments (CTFs) of APP have been shown to be produced in endosomes15, where they can be further processed by γ-secretase16. Consistent with all these observations, various studies have documented abnormal endosomal morphology and increased endosomal Aβ burden in the brain of individuals with AD, suggesting that endosomal dysfunction may be key to AD pathogenesis5,17–19. Importantly, expression studies have identified LOAD-associated deficiencies in a range of molecules related to the retromer pathway, which regulates the sorting of transmembrane proteins from endosomes to the trans-Golgi network (TGN) or the cell surface20–22. These include retromer components (Vps26, Vps29, Vps35) and retromer receptors (SorL1 and SorCS1), which have been implicated in APP sorting and processing1,21–23. Finally, neurons derived from the fibroblasts of patients with presenilin mutations24, APP duplications or LOAD25 show an enlargement of early endosomes. Thus, endosomal dysfunction is increasingly viewed as a key cellular phenotype of AD.

A master organizer of endosomal sorting is the signaling phosphoinositide phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PI3P)26,27, which acts by recruiting to endosomal membranes a variety of effectors containing PI3P-binding modules, such as PX (Phox homology) and FYVE (Fab1, YOTB, Vac1, EEA1) domains27. These effectors control trafficking aspects as diverse as the budding of retromer-coated tubules (e.g., SNX1,2,6,27), the fusion of endosomes (e.g., EEA1) and the ESCRT-dependent intraluminal sorting of ubiquitinated cargos in multivesicular endosomes (e.g., Hrs). A major pathway for the synthesis of PI3P involves class III PI 3-kinase Vps34, which phosphorylates PI on the 3' position of the inositol ring27. Disrupting the function of Vps34 through various approaches causes pleiotropic defects in endosomal function27. Finally, PI3P controls macroautophagy, and regulators of this degradative pathway such as beclin1 act in part through a modulation of Vps34 and show decreased levels in brain from LOAD patients28,29.

As AD pathogenesis is linked to endosomal anomalies, we hypothesized that a perturbation of PI3P metabolism may occur in brain regions most affected by the disease and that this disruption could contribute to pathogenic processes. Our study shows a selective PI3P deficiency in the prefrontal cortex and entorhinal cortex of LOAD-affected individuals as well as in FAD mouse models. We further show that silencing Vps34, and thus reducing PI3P levels, recapitulates several features of AD, including endosomal anomalies and enhanced amyloidogenic processing of APP. Additionally, we establish that APP is both ubiquitinated and sorted into endosomal intraluminal vesicles via the PI3P-dependent ESCRT pathway with major implications for its metabolism. Together, our results identify the PI3P-ESCRT pathway as a novel contributing factor in APP biology and potentially, AD pathogenesis.

RESULTS

PI3P levels are decreased in AD-affected brains

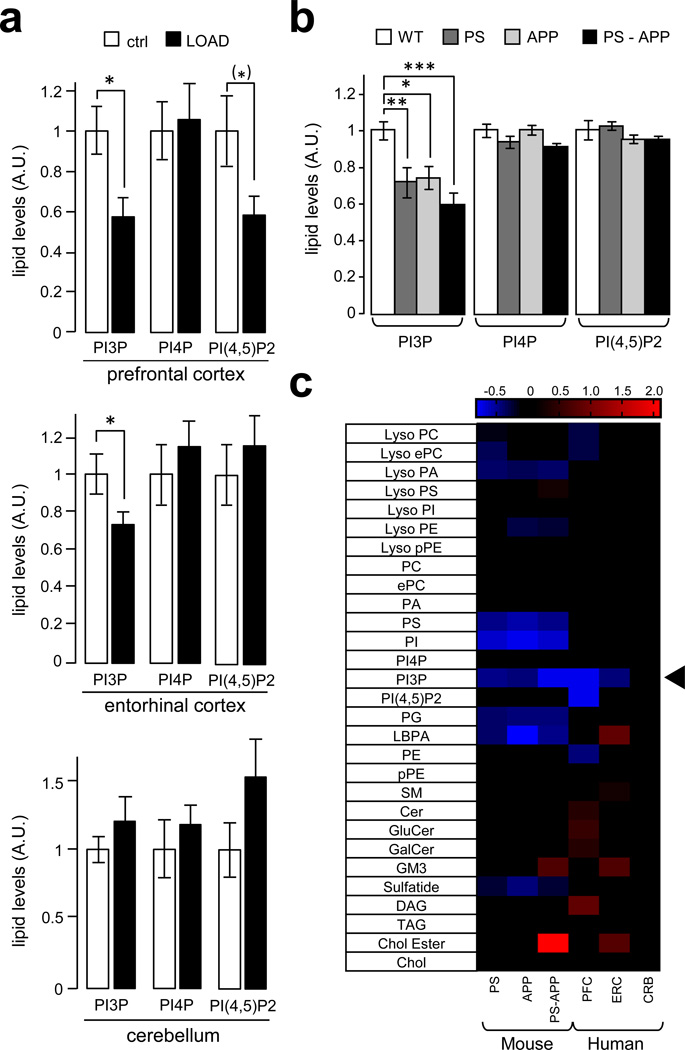

To test if PI3P levels are aberrant in brain regions affected with LOAD, we optimized the HPLC-mediated separation of PI3P and PI4P and were able to detect and quantify these two lipids using suppressed conductivity30,31 (Supplementary Fig. S1). Brain regions affected in AD [prefontal cortex (PFC) and entorhinal cortex (ERC)] or relatively spared (cerebellum, CRB) were analyzed. While PI4P levels were unchanged, a deficiency of PI(4,5)P2 was observed in the PFC of AD patients, consistent with our studies showing that the metabolism of this lipid is disrupted by Aβ, particularly at synapses31,32. Importantly, a significant decrease in PI3P was found in PFC (~40%) and, to a lower extent, ERC (~25%), but not in the CRB from AD patients (Fig. 1a). PI3P levels were also measured in the forebrain of three commonly used transgenic mouse models of familial AD (FAD), namely (i) PSEN1M146V (PS), (ii) the Swedish mutant of APPK670N,M671L (APP) and (iii) PS-APP double transgenic lines33. We found a selective decrease in PI3P levels in each of the mouse model of FAD (i.e., a ~25% decrease in the APP and PS1 models and a ~40% decrease in the PS1-APP model) (Fig. 1b). Importantly, when the phosphoinositide data was combined with a recent mass spectrometry-based lipidomic analysis of the same samples33 and expressed as a heat map, the PI3P deficiency was the only lipid alteration common to both human and mouse brain affected with AD out of ~330 lipid species and 29 lipid classes (Fig. 1c). These data indicate that the deficiency of PI3P observed in both LOAD- and FAD-affected brains is highly selective.

Figure 1. PI3P levels are decreased in human and mouse brain affected by AD.

a) Bar diagram showing relative phosphoinositide levels in prefrontal cortex, entorhinal cortex and cerebellum from post-mortem brains of either non-Alzheimer disease human subjects (ctrl) or late-onset Alzheimer disease human subjects (LOAD). Measurements were made by anionic exchange HPLC with suppressed conductivity detection and expressed in arbitrary units, relative to control levels. Values are shown as means ± SEM (prefrontal cortex, ctrl n=10 and LOAD n=10; entorhinal cortex and cerebellum, ctrl n=12 and LOAD n=15). The PI(4,5)P2 deficiency in the PFC was significant (P < 0.05) with a one-tailed Student's t-test and is indicated by (*) (see Methods). Otherwise single asteriks denote P values < 0.05 from a One-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey test.

b) Bar diagram showing relative phosphoinositide levels in the forebrain of FAD mouse models. These include the PSEN1M146V (PS), the Swedish mutant of APPK670N,M671L (APP) and the PS-APP double transgenic lines. Measurements were made by anionic exchange HPLC with suppressed conductivity detection and expressed in arbitrary units, relative to control levels. Values are shown as means ± SEM (n=6). *, **, and *** denote P values < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001 from a One-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey test.

c) Heat map showing all lipid classes measured and organized according to phospholipids, sphingolipids and neutral lipids classification. The PS, APP, PS-APP columns represent the normalized values of the individual lipid species of mutant mice compared to wild type mice while the PFC, ERC and CRB columns represent the normalized values of the individual lipid species of LOAD patients compared to control patients for each tissue type. The color bars represents the log2 value of the ratio of each lipid species and only statistically significant changes are shown (P < 0.05). Prefrontal cortex, ctrl n=10 and LOAD n=10; entorhinal cortex and cerebellum, ctrl n=12 and LOAD n=15. The arrowhead indicates the PI3P change.

APP is found on PI3P- and Vps34-positive endosomes

We next investigated the relationship between APP, Vps34, and its product PI3P using confocal microscopy. Attempts to localize endogenous Vps34 were unsuccessful due to the lack of specific antibodies, so HeLa cells were transfected with tagged constructs of Vps34 (Vps34RFP), APP (APPmyc), and a genetically-encoded probe for PI3P, i.e. the tandem FYVE domain of EEA1 (FYVE-FYVEGFP)34. We found that the majority of APP immunoreactivity localizes to Vps34RFP- and PI3P-positive structures (Supplementary Fig. S2a), consistent with their predominant localization in endosomes. Both Vps34RFP and APPmyc colocalized with endogenous markers of early (EEA1) and, to a lesser extent, late (LAMP1) endosomal compartments (Supplementary Fig. S2b and S3a,b). Of note, while ~65% of APP colocalizes with EEA1, a smaller pool (~ 35%) is found in the late Golgi, as revealed by an anti-giantin staining (Supplementary Fig. S2b), consistent with previous literature (see for instance ref.35). Not only full length APP, but also its CTFs were found to be enriched in endosomes obtained by subcellular fractionation of HeLa cell extracts (Supplementary Fig. S3c), suggesting extensive processing of APP in these organelles. Finally, because Vps34 has been implicated in autophagosome formation and maturation29 and that APP processing can also occur in these structures36, we examined the localization of APPRFP and the autophagosomal marker LC3 upon starvation and found no colocalization (Supplementary Fig. S3d), suggesting that APPRFP does not traffic through autophagosomes, at least under these conditions. Together, these data show a tight association between APP and the Vps34- and PI3P-positive endosomes.

Silencing Vps34 enhances amyloidogenic processing of APP

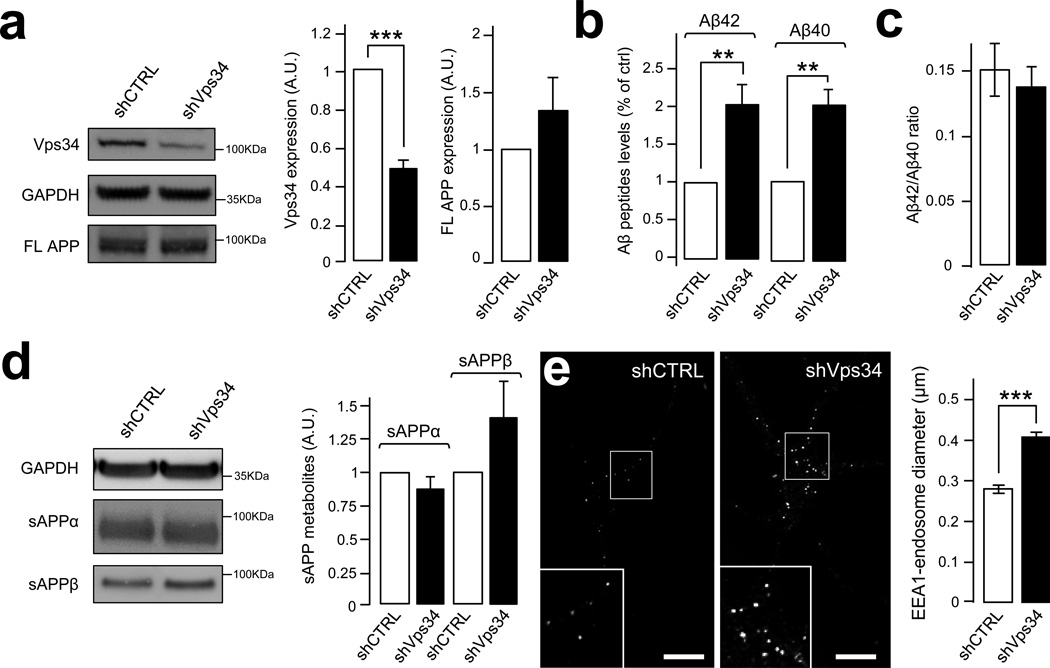

We next investigated the impact of PI3P deficiency on the processing of endogenous APP. Lentiviruses expressing short hairpin RNAs against murine Vps34 (shVps34) or control shRNAs (shCTRL) were used to infect mature primary cortical neurons for 7 days. Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels were subsequently analyzed in media. In the shVps34 conditions (Fig. 2a), levels of Aβ42 and Aβ40 peptides were each increased by ~2-fold (Fig. 2b), with no change in the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio (Fig. 2c). Full length APP showed a trend for an increase (Fig. 2a), although the APP mRNA was not upregulated (1.007 ± 0.002 for the shVps34 condition compared to 1.000 ± 0.318 for the shMock condition, in normalized units, P > 0.05). Levels of the secreted fragment of APP produced by α-secretase (sAPPα) were not affected by shVps34 although a trend for an increase in the levels of sAPPβ was observed (Fig. 2d). Unfortunately, endogenous APP CTFs were not detectable. Importantly, silencing Vps34 produced a ~45% increase in the size of EEA1-positive endosomal puncta (Fig. 2e), consistent with previous studies37. Together, these data demonstrate that a deficiency of Vps34 causes endosomal abnormalities and enhances the amyloidogenic processing of APP in neurons, establishing a link between PI3P deficiency, endosomal dysfunction and AD pathogenesis.

Figure 2. Silencing of Vps34 leads to increased amyloidogenic processing of neuronal APP.

a) Western blot analysis (left panel) of endogenous Vps34 and full-length APP (FL-APP) levels in cultured mouse cortical neurons infected with Vps34 shRNA lentivirus (shVps34) or a control lentivirus (shCTRL). GAPDH was used as an equal loading marker. The graphs show the quantification of Vps34 levels (middle panel) and FL-APP levels (right panel) in arbitrary units. Values denote means ± SEM (n=17). *, denotes P values < 0.05 from a Student's t-test.

b) Bar diagram showing murine Aβ42 and Aβ40 levels measured by ELISA from cultured cortical neuron media, after infection with shCTRL or shVps34 lentiviruses. Aβ levels were normalized to the cell lysate total protein. Values are shown as means ± SEM (n=13). **, denotes P values < 0.01 from a Student's t-test.

c) Bar diagram showing the Aβ42/ Aβ40 ratio measured from experiments described in (b) and shown as means ± SEM (n=13).

d) Quantification of secreted APP metabolites derived from the cleavage of murine APP by α-secretase (sAPPα) or β-secretase (sAPPβ) after infection of cultured cortical neurons with shCTRL or shVps34 lentiviruses. Left panel, Western blot analysis of secreted fragments in the media alongside the loading control GAPDH. Right panel, Bar diagram showing the quantification of sAPPα (left bars) and sAPPβ levels (right bars) after normalization of their levels to the cell lysate total protein. Values denote means ± SEM (sAPPα n=7, sAPPβ n=5).

e) Confocal analysis of cultured mouse cortical neurons infected with shCTRL or shVps34 lentiviruses and stained with an EEA1-specific antibody. Left panel, representative immunostainings. Scale bar= 10µm. Right panel, Bar diagram showing the average diameter of EEA1-positive endosomal fluorescent puncta. Values denote means ± SEM (n=82). ***, denotes P values < 0.001 from a Student's t-test.

Silencing Vps34 perturbs APP trafficking

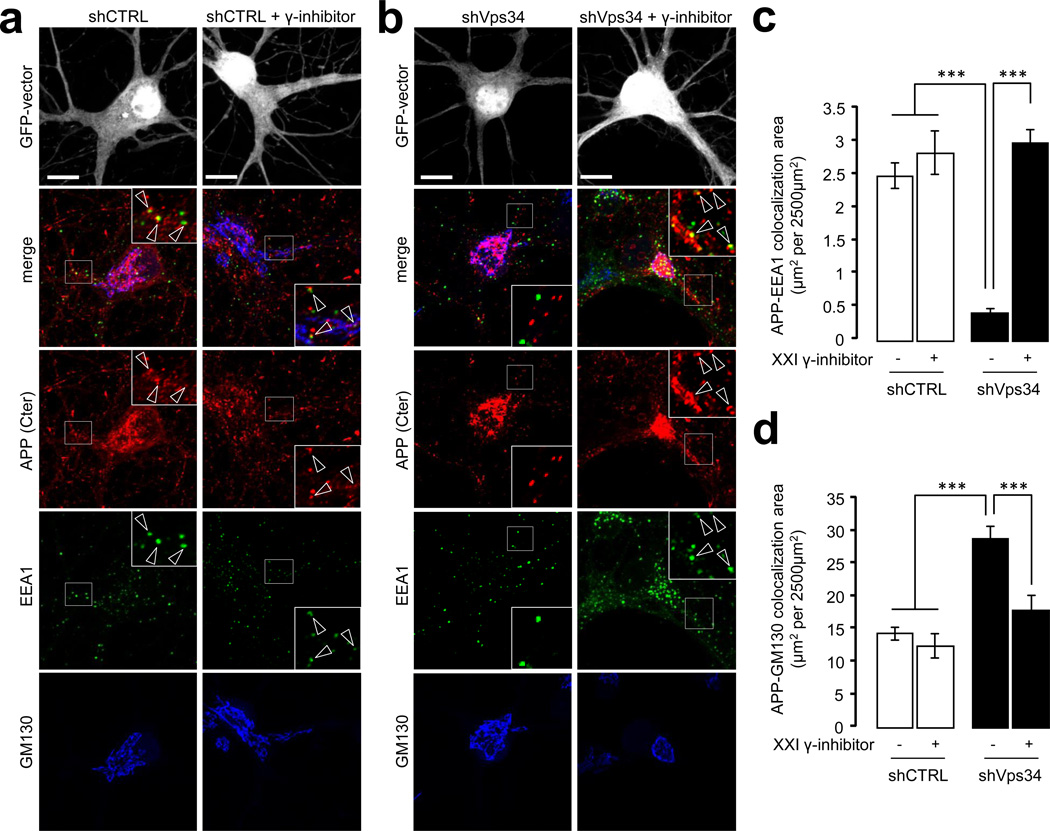

To test whether silencing Vps34 perturbs the endosomal localization of APP, we conducted confocal analyses of primary neurons immunostained with antibodies to the cytodomain of endogenous APP as well as to EEA1 and GM130, in order to label the endosomal and Golgi compartments, respectively (Fig. 3a,b). Silencing Vps34 produced a major loss of APP fluorescence from EEA1-positive endosomes (Fig. 3c) and an apparent and relative increase in the Golgi compartment, which primarily reflects the loss of endosomal fluorescence (Fig. 3d). Because γ-secretase releases the cytodomain of APP in the cytosol, loss of the APP cytodomain immunoreactivity from endosomes may reflect increased processing of APP CTFs by γ-secretase due to Vps34 silencing. To test this, neurons infected with the shCTRL or shVps34 lentiviruses were treated with vehicle or a γ-secretase inhibitor, compound XXI. While the γ-secretase inhibitor did not affect the localization of APP in shCTRL-treated neurons, it fully restored the normal distribution of APP in shVps34-treated neurons (Fig. 3c,d). These data suggest that the increased processing of APP occurring upon silencing of Vps34 primarily takes place in endosomes (although minor contributions from the Golgi cannot be excluded) and prompted us to investigate the precise role of this enzyme and its product PI3P in the endosomal sorting of APP.

Figure 3. Silencing of Vps34 alters the subcellular localization and processing of endogenous APP.

a) Mouse hippocampal neurons were transfected with shCTRLGFP plasmid at DIV8 and cultured for 3 days before a 24 h treatment with vehicle (left panel) or γ-secretase inhibitor compound XXI at 10µM (right panel). Neurons were then fixed, stained for the indicated antibodies (anti-GM130, blue channel, anti-EEA1, green channel and anti-APP COOH-terminus (C-term) antibody, red channel) and imaged using confocal microscopy. Scale bar = 10 µm. Arrowheads indicate structures showing colocalization between APP and EEA1.

b) Mouse hippocampal neurons were transfected with shVps34GFP and processed as described in (a).

c) Bar diagram showing the amount of colocalization between APP and EEA1 per 2500 µm2 of image cell surface area following expression of shCTRLGFP (see a) or shVps34GFP (see b) in cultured neurons, in the presence or absence of γ-secretase inhibitor XXI. Results are shown as means ± SEM (n=30 cells). The asterisks denote P values < 0.001 from a Student's t-test.

d) Bar diagram showing the amount of colocalization between APP and GM130 per 2500 µm2 of image cell surface area following expression of shCTRLGFP (see a) or shVps34GFP (see b) in cultured neurons, in the presence or absence of γ-secretase inhibitor XXI. Results are shown as means ± SEM (n=28 cells). The asterisks denote P values < 0.001 from a Student's t-test.

APP is sorted into the ILVs of multivesicular endosomes

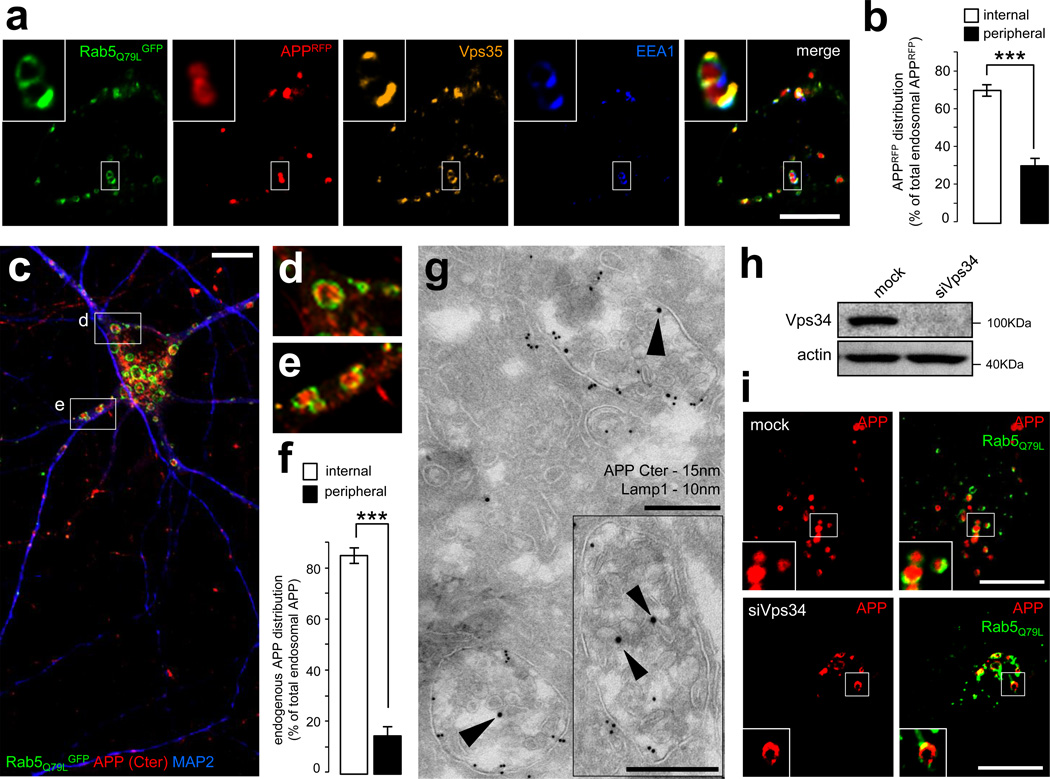

A key function of Vps34 and PI3P is to control the sorting of cargos into intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) of multivesicular endosomes via the ESCRT pathway, which typically ensures their degradation in lysosomes 38,39. We thus tested whether aberrant processing of APP caused by Vps34 deficiency reflects a contribution of this pathway. To begin to address this issue, we attempted to visualize intraluminal APP in HeLa cells using confocal microscopy following expression of APPRFP and the constitutively active form of Rab5, Rab5Q79LGFP, which is locked in its GTP-bound form15,40. This mutant is known to produce an enlargement of endosomes, allowing for the discrimination between the limiting membrane of these organelles and their lumen, which contains the ILVs. Under these conditions, APPRFP, and likely CTFs thereof, were mostly observed within the endosomal lumen, in contrast to endosomal markers known to be associated with the limiting membrane, including Rab5 itself, EEA1, or the retromer component Vps35 (Fig. 4a). Analysis of APPRFP- and Rab5Q79LGFP-positive endosomes showed that ~70% of these structures display luminal fluorescence, likely reflecting an association of APPRFP with ILVs (Fig. 4b). Comparable results were obtained with the CTFβ (data not shown; see also ref.15). Immuno-electron microscopic (EM) analysis of APPGFP using anti-GFP antibodies showed gold particles inside multivesicular structures, confirming the light microscopic observations (Supplementary Fig. S4a). Importantly, endogenous APP was also predominantly found (~80%) in the lumen of enlarged endosomes in cultured neurons expressing Rab5Q79LGFP, as shown by the immunostaining of its cytodomain (Fig. 4c–f). The luminal localization of the APP cytodomain was also found in naturally-occurring enlarged endolysosomal structures as shown by costainings with anti-EEA1, -Vps35 and -LAMP1 antibodies (Supplementary Fig. S4b). Importantly, immuno-EM labeling of neurons with antibodies to APP cytodomain showed gold particles associated with ILVs of multivesicular endosomes, which were also LAMP1-positive (Fig. 4g).

Figure 4. APP is sorted into the intraluminal vesicles of multivesicular endosomes.

a) Confocal analysis of HeLa cells transfected with APPRFP (red) and the dominant-positive Rab5Q79LGFP mutant (green), which was used for its ability to generate giant endosomes. The cells were fixed and labeled with anti-EEA1 (blue) and anti-Vps35 (orange) antibodies. Scale bar = 10µm.

b) Bar diagram showing a quantification of the localization of APPRFP inside the endosomal lumen (internal) vs. on the endosomal limiting membrane (peripheral), expressed as % of the total endosomal APPRFP. Values denote means ± SEM (n = 20 cells from 3 experiments with an average quantification of 15 endosomes per cell). ***, denotes P values < 0.001 from a Student's t-test.

c) Confocal analysis of mouse hippocampal neurons transfected with Rab5Q79LGFP (green) at DIV9 and stained for endogenous APP (using the Cter antibody, red) and MAP2, a marker of the somatodendritic compartment (blue). Two insets are selected and presented in panels (d) and (e). Scale bar = 10 µm.

d) First inset showing a magnification of the area containing enlarged endosomes presented in panel (c).

e) Second inset showing a magnification of the area containing enlarged endosomes presented in panel (c).

f) Bar diagram showing the quantification of the endosomal localization of endogenous APP in neurons, as in panel (b).

g) Immunogold EM analysis of mouse hippocampal neurons at DIV15 in ultrathin cryosections double-labeled with antibodies to endogenous APP COOH-terminal domain (APP C-ter; PAG 15nm, arrowheads), located primarily on the intraluminal vesicles, and LAMP-1 (PAG 10nm). Scale bars = 250 nm.

h) Western blot analysis of endogenous Vps34 and the loading marker actin in HeLa cells transfected with mock siRNA (mock) or siRNA against human Vps34 (siVps34) followed by transfection with APPRFP and Rab5Q79LGFP.

i) Confocal analysis of HeLa cells transfected with mock siRNA (mock, top panel) or siVps34 (bottom panel) for 72h and then split, prior to transfection with APPRFP and Rab5Q79LGFP. Scale bar = 10µm.

To determine if the pool of APP found on ILVs originates from the plasma membrane, we performed an anti-APP ectodomain antibody (22C11) uptake experiment in HeLa cells co-expressing APPRFP and Rab5Q79LGFP (Supplementary Fig. S4c). After antibody binding at 4°C and 3h of treatment with protein synthesis inhibitor (cycloheximide, CHX), the 22C11 immunoreactivity was mostly found at the plasma membrane, as shown by the punctate staining at the basal plane of the cells (Supplementary Fig. S4c). After a 15min chase period, the 22C11 immunoreactivity was detected primarily on the limiting membrane of endosomes (Supplementary Fig. S4d). After 30min, the APPRFP fluorescence (labeling the COOH-terminus) and the 22C11 fluorescence (labeling the NH2-terminus) converged in part in the lumen of endosomes (Supplementary Fig. S4d). Thus, the pool of APP that is sorted into the ILVs originates from the plasma membrane and is endocytic in nature (although a pool of cell surface-derived APP also traffics to the TGN via endosomes) (see for instance ref.41).

Vps34 controls the intraluminal sorting of APP in endosomes

To test whether targeting of APP to ILVs is PI3P-dependent, we analyzed the acute effect of wortmannin, a chemical inhibitor of class I and class III PI 3-kinases. To monitor PI3P levels, HeLa cells were transfected with FYVE-FYVEGFP together with APPRFP and subjected to a 30 min treatment with 100nM wortmannin. As expected, the drug dramatically decreased the association of FYVE-FYVEGFP with endosomes, labeled with EEA1 and Vps35 (Supplementary Fig. S5a). While the localization of retromer was perturbed by this treatment, no marked phenotype was observed for APPRFP (Supplementary Fig. S5a). However, when this experiment was repeated after Rab5Q79LGFP expression to visualize the endosomal lumen (Supplementary Fig. S5b), APPRFP was relocalized from the lumen of giant endosomes to their limiting membrane. The ratio of internal/peripheral APPRFP fluorescence in giant endosomes was quantified following wortmannin treatment in a time course-dependent fashion. APPRFP relocalization occurred very rapidly, as early as 10 min after the beginning of the treatment (Supplementary Fig. S5b). HeLa cells were also transfected with siRNAs targeting Vps34 (siVps34) or control siRNAs (MOCK), grown for 72h, and then transfected with APPRFP and Rab5Q79LGFP. The potent inhibition of Vps34 protein expression was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 4h) and the reduction in the levels of PI3P was confirmed with a microscopic analysis of the fluorescent pattern of the FYVE-FYVE probe, either used as a GST fusion for the staining of fixed cells34 (Supplementary Fig. S6a and S6b) or as a genetically-encoded GFP fusion (Supplementary Fig. S6c). Additionally, the silencing of Vps34 produced a significant loss of membrane association of retromer component Vps35, consistent with reduced levels of PI3P (Supplementary Fig. S6d). As observed with wortmannin, APPRFP was mostly localized to the limiting membrane of endosomes upon siVps34 treatment (Fig. 4i; quantification shown in Supplementary Fig. S7c), thus confirming the essential role of Vps34-mediated PI3P synthesis in the ILV sorting of APP.

The targeting of APP to ILVs is ESCRT-dependent

A key player initiating the ESCRT cascade is Hrs, also known as an ESCRT0 component, which binds PI3P via a FYVE domain and ubiquitinated cargoes via a ubiquitin interacting motif (UIM)38,39. To investigate if Hrs, like Vps34, plays a role in the intraluminal sorting of APP, HeLa cells were transfected with siRNAs targeting Hrs (siHrs). Silencing Hrs (Supplementary Fig. S7a) produced an accumulation of APPRFP fluorescence on the limiting membrane of endosomes similar to siVps34 (Supplementary Fig. S7b,c). Comparable results were obtained upon silencing of ESCRT-I subunit Tsg101 and, to a lesser extent, SNX3, which has been shown to mediate the formation of ILVs in multivesicular endosomes42 (Supplementary Fig. S7). In contrast, silencing of beclin1, a major regulator of Vps34 in autophagy, did not affect the intraendosomal localization of APP (Supplementary Fig. S7). Together, our data demonstrate that the Vps34/PI3P/ESCRT pathway controls the intraluminal sorting of APP.

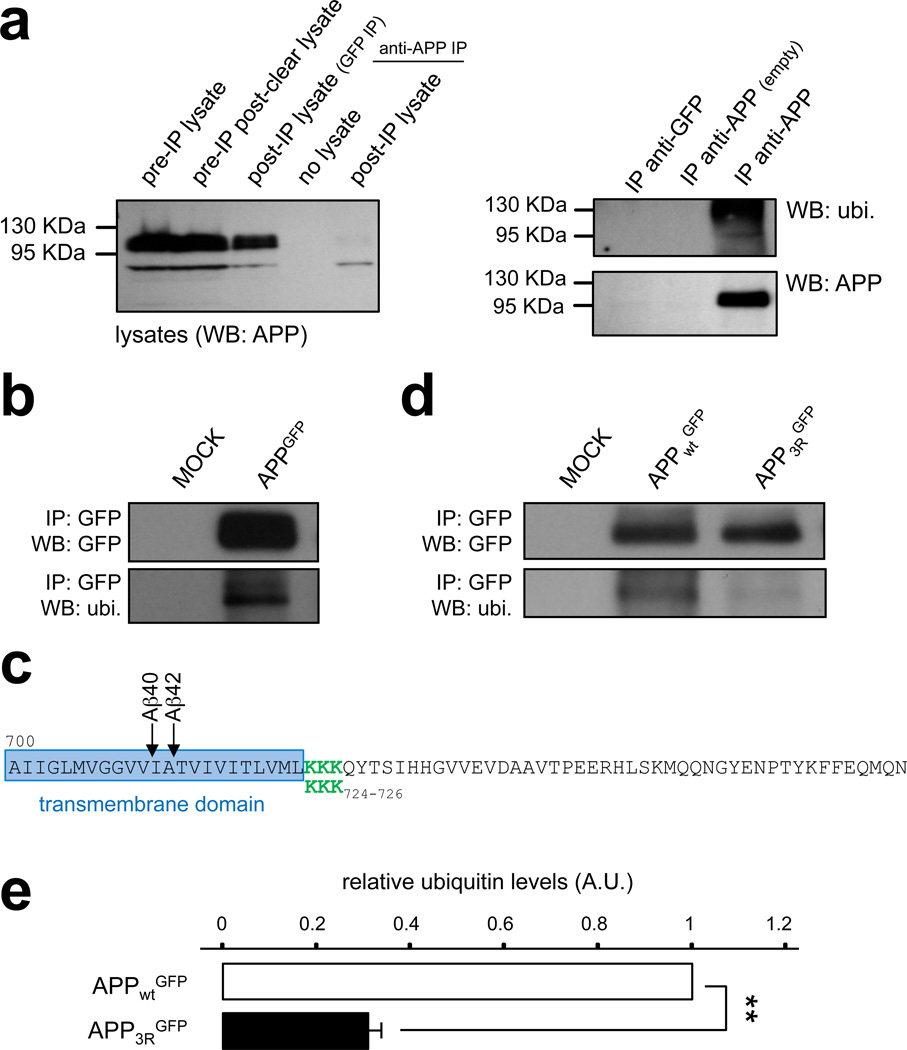

The targeting of APP to ILVs depends on its ubiquitination

The signal triggering ESCRT-mediated internalization of cargoes from the limiting membrane of endosomes to ILV is ubiquitination of their cytodomain on lysine residues39,43. We therefore tested whether endogenous APP is ubiquitinated in the brain. APP was immunoprecipitated from mouse brain extracts using anti-APP cytodomain antibodies and bound material was analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-APP and -ubiquitin antibodies (Fig. 5a). Ubiquitin immunoreactivity was found to co-migrate with APP, but not control eluate, indicating that endogenous APP is indeed ubiquitinated.

Figure 5. The sorting of APP into intraluminal vesicles depends on ubiquitination.

a) Mouse brain extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with an anti-APP-Cter antibody, or a control antibody (anti-GFP). Left panel: Western blot analysis of the starting lysates, the post-preclearing lysate (pre-IP), the lysate post-IP with anti-GFP, the control buffer post-IP with anti-APP-Cter, and the lysate post-IP with anti-APP-Cter. The immunoblot was performed with an anti-APP-Cter antibody. Right panel: Western blot analysis of the immunoprecipitated material shown in (a) using the anti-GFP antibody (IP anti-GFP), the control immunoprecipitation with anti-APP-Cter without brain lysate (IP anti-APP empty), and the anti APPCter antibody (IP anti-APP). The immunoblot was performed with an anti-ubiquitin antibody (top panel, ubi.), followed by stripping, and incubation with an anti-GFP antibody (bottom panel). IP: immunoprecipitated material; WB: Western blot.

b) HeLa cells were transfected with APPGFP or a mock construct. Total lysates were subjected to an immunoprecipitation with an anti-GFP antibody. Samples were analyzed by SDS-page and Western blotting with an anti-ubiquitin antibody (bottom panel, ubi.), followed by stripping, and incubation with an anti-GFP antibody (top panel). IP: immunoprecipitated material; WB: Western blot.

c) COOH-terminal sequence of human APP. The transmembrane domain is framed in blue, and Aβ peptide-cleavage sites are indicated with arrows. The juxtamembrane lysine residues at position 724–726 are depicted in green, and were substituted with 3 arginines in the APP3R mutant.

d) HeLa cells were transfected with human APPGFP (APPWTGFP), the APP mutant (APP3RGFP), or not transfected (mock) and total lysates were prepared. After immunoprecipitation with an anti-GFP antibody, protein samples were analyzed by SDS-page and Western blotting with an anti-ubiquitin antibody (bottom panel) followed by stripping and incubation with an anti-GFP antibody (top panel). IP: immunoprecipitated material; WB: Western blot.

e) Bar diagram showing the quantification of relative ubiquitin levels in APPWT and the APP3R mutant. (A.U.: arbitrary units). Values denote means ± SEM (n=3). **, denotes P values < 0.01 from a Student's t-test.

To determine the main ubiquitination sites relevant for ILV sorting, HeLa cells were transfected with APPGFP and lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-GFP antibodies. Immunoblotting of the immunoprecipitated material with an anti-ubiquitin antibody revealed that APPGFP is also ubiquitinated (Fig. 5b), similar to endogenous APP. A stretch of three lysines located in the cytoplasmic juxtamembrane region on positions 724–726 of human APP were good candidate ubiquitination sites (green residues in Fig. 5c), based on evidence from others indicating that lysines in the juxtamembrane region of proteins can be ubiquitinated44 and the recent finding that lysine 726 ubiquitination is relevant for proteasomal degradation of APP under conditions of overexpression of F box factor FBL245. To determine the role of these lysines, an APP mutant in which lysines 724–726 were substituted with arginines (referred to as APP3RGFP) was expressed in HeLa cells and showed a dramatic reduction in the ubiquitin signal relative to the control (Fig. 5d,e).

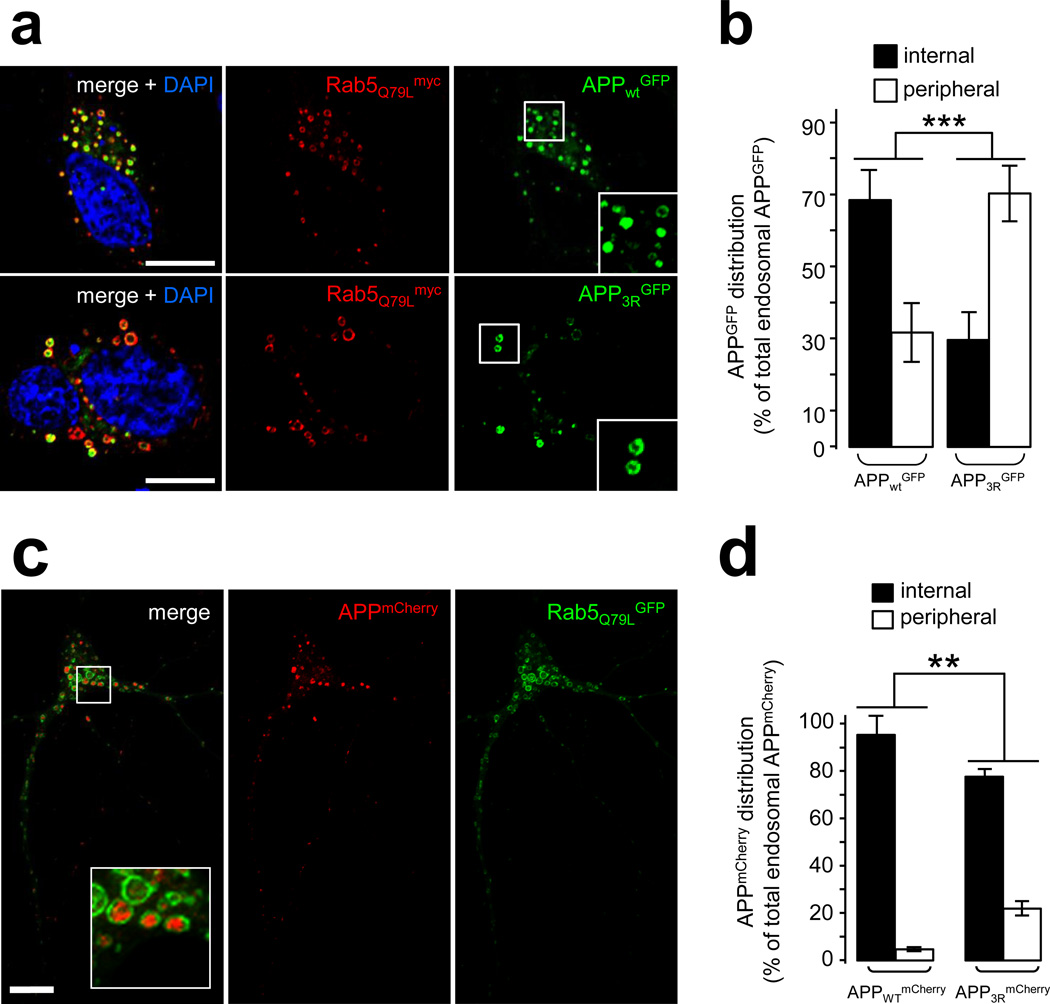

To test if ubiquitination of these lysine residues is critical for ILV sorting, we expressed APP3RGFP and Rab5Q79Lmyc and examined the targeting of mutant APP to ILVs in giant endosomes. We found that APP3RGFP displayed a predominant association with the limiting membrane of endosomes at the expense of luminal localization (Fig. 6a,b). When expressed in hippocampal neurons alongside Rab5Q79LGFP, APP3R also exhibited decreased targeting to the lumen of enlarged endosomes relative to APPWT (Fig. 6c,d), although the missorting was not as striking as that observed in HeLa cells. Importantly, treatment with γ-secretase inhibitor (compound XXI) was applied in these experiments to enhance and better visualize the endosomal pool of APP, which otherwise undergoes significant processing by the secretase (see below). Together, our results demonstrate that ubiquitination of the cytodomain of APP on one or more of lysines 724–726 is important for the intraluminal sorting of APP through the Vps34/PI3P/ESCRT pathway.

Figure 6. Blocking the intraluminal sorting of APP enhances its amyloidogenic processing.

a) Confocal analysis of HeLa cells transfected with Rab5Q79Lmyc and APPWTGFP (top panel) or APP3RGFP (middle panel). Cells were labeled with an anti-myc antibody (red) and counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 10µm.

b) Bar diagram showing the quantification of the endosomal distribution of human APPGFP expressed as % of total endosomal APPGFP: internal = inside endosomal lumen, peripheral = limiting membrane of the endosomes. Values denote means ± SEM (for each construct, n = 18 cells from 3 experiments with an average quantification of 15 endosomes per cell). ***, denotes P values < 0.001 from a Student's t-test.

c) Confocal analysis of mouse hippocampal neurons transfected at DIV9 with Rab5Q79LGFP and APPWTmCherry and fixed after a 24 h treatment with γ-secretase inhibitor XXI. Scale bar =10 µm. The inset shows APP-containing endosomes.

d) Bar diagram showing the quantification of the endosomal distribution of human APPWTmCherry and APP3RmCherry in hippocampal neurons processed as described in (c). The APPmCherry distribution is expressed as % of total endosomal APPmCherry: internal = inside endosomal lumen, peripheral = limiting membrane of the endosomes. Values denote means ± SEM (n=45 and 18 cells for APPWTmCherry and APP3RmCherry, respectively from 3 experiments with an average quantification of 20 endosomes per cell). **, denotes P values < 0.01 from a Student's t-test.

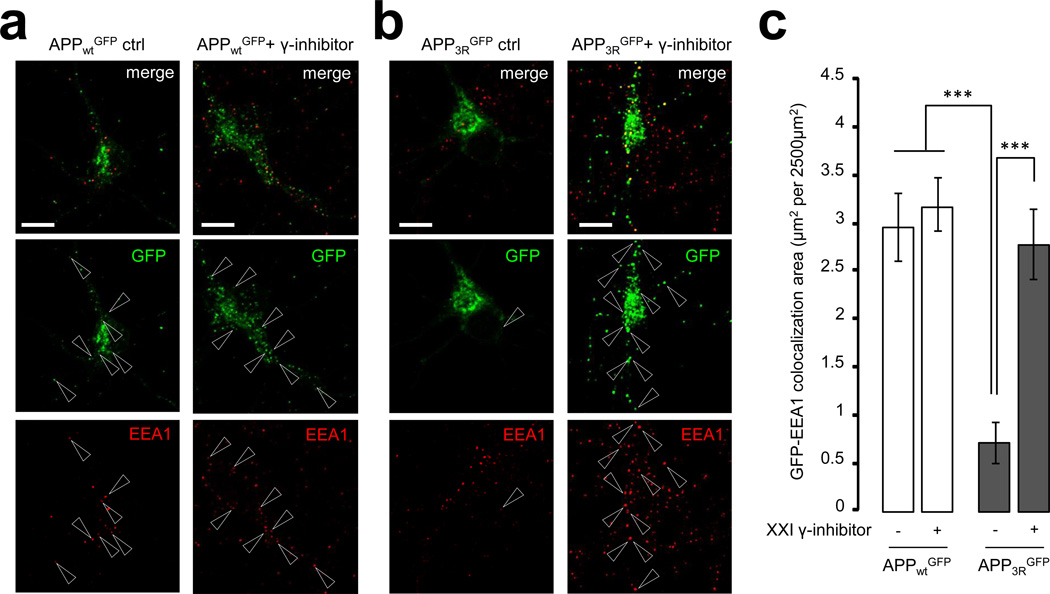

The APP-3R mutant shows altered sorting in neurons

Silencing Vps34 produced a dramatic loss of endogenous APP fluorescence in neuronal endosomes, a phenotype rescued by γ-secretase inhibitor treatment. If a key function of PI3P is to promote ILV sorting of APP into multivesicular endosomes through ESCRT, the traffic pattern of APP3R may phenocopy that of wild-type APP obtained upon Vps34 silencing. As hypothesized, the association of APP3R with neuronal endosomes positive for EEA1 (Fig. 7) or Vps35/retromer (Supplementary Fig. S8) was dramatically reduced, while that with the GM130-positive Golgi compartment was slightly enhanced (Supplementary Fig. S9) relative to APPWT. As seen with the Vps34 knockdown, treatment of neurons with the γ-secretase inhibitor restored the normal distribution of APP3R (Fig. 7, S8 and S9), although within endosomes, the APP3R mutant was preferentially localized on the limiting membrane (Fig. 6c,d).

Figure 7. Decreasing the ubiquitination of APP alters its subcellular localization in primary neurons.

a, b) Mouse neurons were transfected with human APPwtGFP (in a) and APP3RGFP (in b) plasmids at DIV9. After 24h expression in the presence (right panels) or absence (left panels) of γ-secretase inhibitor compound XXI, neurons were fixed, stained for EEA1 (red channel) and imaged with confocal microscopy. Scale bar = 10 µm. Arrowheads indicate structures where APPGFP and EEA1 colocalize

c) Bar diagram showing the amount of colocalization between GFP and EEA1 per 2500 µm2 of image cell surface area following expression of APPwtGFP and APP3RGFP in cultured neurons, in the presence or absence of γ-secretase inhibitor XXI. Results are shown as means ± SEM (APPwtGFP, n=30 and APP3RGFP, n=20). ***, denotes P values < 0.001 from a Student's t-test.

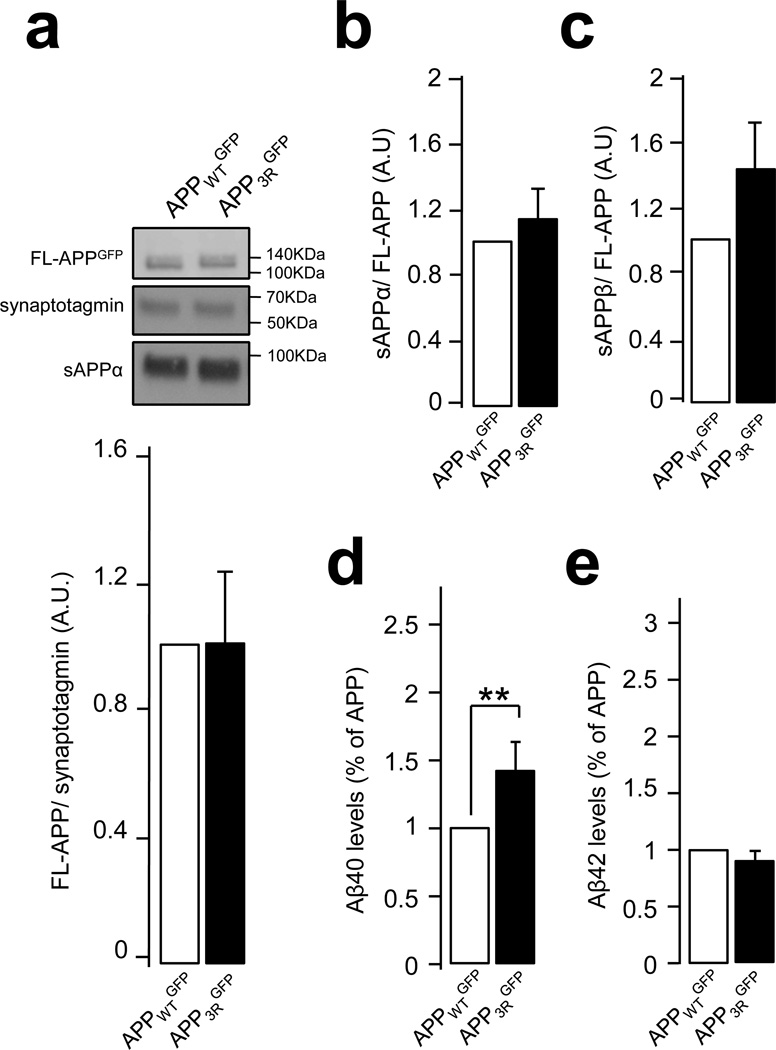

Inhibiting ILV sorting of APP enhances Aβ levels

Our data suggest that APP3R is more extensively processed through the amyloidogenic pathway in endosomes, similar to endogenous APP in the Vps34 knockdown. We thus examined the impact of the 3R mutation on the metabolism of APP expressed exogenously with lentivirus in primary neurons (in the absence of Rab5Q79L expression). Constructs were comparably expressed, based on the lack of differences found for FL-APPWT and APP3R (Fig. 8a). Similar to the Vps34 knockdown, sAPPα levels were unchanged (Fig. 8b), while a trend for an increase in sAPPβ was found for the APP3R mutant (Fig. 8c). Consistent with this trend, expression of APP3R caused a ~50% increase in Aβ40, although surprisingly Aβ42 levels were unchanged (Fig. 8d). Together, these data indicate that mutations that decrease the intraluminal sorting of APP in endosomes promote the generation of Aβ.

Figure 8. Expression of the APP-3R mutant leads to an increase in secreted Aβ.

a and b) Mouse neurons were infected with lentiviruses expressing human APPWTGFP and APP3RGFP at DIV 7. At DIV 14, secreted APP metabolite sAPPα was analyzed by SDS-page and Western blot (in a and b), while secreted APP metabolite sAPPβ was measured by ELISA of culture media (in c). Synaptotagmin was used as an equal loading marker. The graphs show the quantification of full length APP normalized to synaptotagmin (in a) and the quantification of metabolites sAPPα (in b) and sAPPβ levels (in c) as a ratio of metabolite/full length APPGFP. Values denote means ± SEM (n=8).

d and e) Bar diagram showing the quantification of human Aβ40 (in d) and Aβ42 (in e) peptide levels measured by ELISA in neuronal media after infection of neurons with lentiviruses expressing human APPWTGFP or APP3RGFP. Aβ levels were normalized to the cell lysate total protein and results are expressed as % of APPWTGFP. Values denote means ± SEM (n=13). **, denotes P values < 0.01 from a Student's t-test.

DISCUSSION

Cell biological observations combined with results from expression and genetic profiling have suggested that defects in endosomal sorting and trafficking play a pathogenic role in AD1,4,5. Together with studies suggesting that amyloidogenic processing of APP predominantly occurs in endosomes, these reports indicate that these organelles are critical players in AD pathogenesis. Our study strongly supports this hypothesis by identifying a molecular defect, namely a selective deficiency in PI3P, in affected brain regions from patients with LOAD as well as in the forebrain of mouse models of FAD. Remarkably, the deficiency of PI3P is the only lipid change common to both human and mouse brains affected by AD out of ~330 lipid species examined. Because the PI3P deficiency does not correlate with the extent of neuronal death or AD pathology in AD-affected regions, it is unlikely to merely stem from neurodegeneration, although it may also reflect changes occurring in glial cells.

PI3P controls fundamental aspects of endosomal membrane dynamics26,27,39. Additionally, PI3P regulates macroautophagy, which mediates via an interplay with endolysosomal compartments the clearance of defective organelles and intracellular aggregates, and has also been implicated in AD29,36. While a deficiency of PI3P in AD may theoretically cause any of the abovementioned PI3P-dependent processes to function suboptimally, our study provides strong evidence that it affects endosome dynamics as well as the sorting and processing of APP, all of which are believed to play a role in AD pathogenesis. Indeed, modeling the PI3P deficiency by silencing Vps34, the main source of PI3P, produces endosomal enlargement, a perturbation of APP trafficking as well as increased production of Aβ. Interestingly, these phenotypes are partially shared in common by instances in which Rab5 is overexpressed5,12. However, the link between PI3P deficiency and Rab5 hyperactivation identified in LOAD is unclear, as Rab5 is known to activate Vps3446. We speculate that Rab5 hyperactivation may be compensating for the PI3P deficiency, although these phenomena may not be directly related.

Our cell culture studies indicate that APP is sorted and trafficked via ESCRT, and together with previous studies implicating the retromer pathway, suggest a general mechanism for how PI3P deficiency observed in the disease can lead to APP missorting. In common with recent studies 45,47, we found that APP is ubiquitinated on cytoplasmic lysine residues. However, extending on these observations, we found that ubiquitination, which we document also for the endogenous protein in the brain, mediates targeting of an endocytic pool of APP to ILVs via ESCRT, rather than to proteasomal degradation. Indeed, silencing key ESCRT components, such as Hrs and Tsg101, leads to an accumulation of APP on the limiting membrane of endosomes in HeLa cells. Furthermore, substituting the lysine residues with arginines dramatically impairs ubiquitination of APP and also causes a shift of its localization to the limiting membrane of endosomes. Remarkably, ILV missorting correlates with elevation of Aβ secretion in neurons, although the pattern of secreted Aβ species varies depending on the specific manipulation: while Vps34 silencing causes an increase in both Aβ40 and 42, the APP3R mutant causes a differential elevation in Aβ40. This is consistent with the idea that the PI3P deficiency may also cause defects in APP trafficking and processing independently of those produced by reduced ESCRT-dependent sorting into ILV. In this respect, a key effect of PI3P deficiency may be to cause a dysfunction of retromer, whose knockdown phenocopies the increase in Aβ40 and 42 levels in neurons23. Interestingly, the selective increase in Aβ40 observed with the APP3R mutant may paradoxically confer protection against amyloidogenesis in vivo, based on the ability of this shorter peptide to counteract the aggregate-inducing property of Aβ4248. Regardless, our data suggest that Aβ generation predominantly occurs on the limiting membrane of endosomes, perhaps reflecting the presence there of highly active pools of BACE1 and/or presenilin. This is supported by our experiments showing that γ-secretase inhibitors restore an endosomal pool of APP that is otherwise drastically diminished by the silencing of Vps34 or the 3R mutation of APP. We note that some studies in non-neuronal cell lines have reported experimental manipulations that enhance the Golgi association of APP (at the expense of endosomes) as well as its amyloidogenic processing (see for instance ref.35). The use of γ-secretase inhibitors in those instances should help to resolve whether the loss of endosomal pool reflects enhanced processing in those organelles rather than a bona fide accumulation of APP in the Golgi compartment. We also note that a recent APP overexpression study conducted in non-neuronal cells reported that silencing various "early" ESCRT components (e.g., Hrs, Tsg101) causes a retention of APP in endosomes and a decrease of Aβ40 release. Conversely, silencing "late" ESCRT components (e.g., CHMP6, Vps4) causes enhanced targeting of APP to the TGN and an increase in Aβ40 release41. Future work should address whether these experimental manipulations produce similar results in neurons.

Overall, our study and work from others suggest that the pathogenesis of AD, and LOAD in particular, is linked to the dysfunction of a number of genes involved in trafficking pathways identified in yeast as "vacuolar protein sorting" [e.g., Vps34 and beclin1/Vps30 (PI3K), Hrs/Vps27 and Tsg101/Vps23 (ESCRT), Vps26/29/35 (retromer), SorLa/SorCs1 (Vps10-like proteins)]22,28,49. The identification of PI3P deficiency in affected brain regions of individuals with LOAD not only provides a potential mechanism explaining AD-associated endosomal anomalies and aberrant APP metabolism, but also defects in autophagy28,36, which may reduce clearance of tau aggregates50. The precise genetic and/or environmental factors responsible for PI3P deficiency in FAD and LOAD are unknown, although we speculate they may affect the function of Vps34 complexes, perhaps in combination with that of alternate pathways controlling PI3P levels.

Finally, besides clarifying basic mechanisms of APP biology, our results may have clinical implications. In particular, our data suggest that as an enzyme that regulates PI3P levels, Vps34, as well as other lipid enzymes controlling PI3P levels through dephosphorylation mechanisms (e.g., myotubularins) may be novel targets for drug discovery in attempting to improve APP missorting characteristic of LOAD. In this respect, targeting the metabolism of phosphoinositides and more generally, phospholipids, is emerging as a promising new avenue for AD therapy31,32,51–53. As recent studies have implicated defects either in lipid metabolism or in endosomal sorting in AD, our work establishes an important link between these two intracellular processes, and this converging view also provides a focus for developing novel therapeutic targets and agents.

METHODS

Human and mouse brain tissue

Frozen post mortem brain tissue samples were described previously 33. Three different brain regions were sampled: prefrontal cortex, entorhinal cortex and cerebellum. The diagnostic criteria for AD were based on the presence of neurofibrillary tangles, senile plaques and dementia. Wild-type, PS1, APP and PS1-APP mice, which were aged between 9 to 11.5 months, were described previously 33. All mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, forebrain dissected immediately and frozen in liquid nitrogen before storage at −80°C.

Cell transfection and lentivirus production

HeLa and HEK-293T cells were grown at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator in MEM and DMEM respectively (Invitrogen). HeLa cells were transiently transfected using Fugene-6 (Roche Diagnostics) or Lipofectamine 2000 (invitrogen) for cDNA (from 24h to 48h) and siRNA (72h), respectively. Hippocampal cultures were obtained from P0 mice. Neurons were plated on poly-L-lysine coated coverslips or 6 well plates, and incubated with Neurobasal media (Invitrogen) with 10% FBS. After 5h, neurons were transferred into serum-free medium supplemented with B27 (Invitrogen) and cultured for 9 –12 days in vitro (DIV). In some experiments, neurons cultured for 8–9 days were transfected for 60min with 2µl of Lipofectamine 2000 combined with 1µg of DNA, washed, and incubated for 24h (APPWTGFP, APP3RGFP) or 4 days (shRNA) prior to immunofluorescence analysis. In other experiments, neurons were infected with shRNA lentivirus after 7 days in culture, and cultured up to 14 days. Lentiviruses were generated by transfecting lentiviral vectors (APPWTGFP, APP3RGFP) or a mix of equal amounts of shVPS34-1 and shVPS34-2 into HEK-293T cells using lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen). A pPACK-H1 packaging mix (System Biosciences) was added to the transfection reagents according to the manufacturer's instructions. The medium was collected 48h and 72h post transfection, passed through a 45nm filter, and applied at 1:4 ratio to media.

Antibodies and reagents

Antibodies were obtained from the following sources: rabbit polyclonal antibodies to Vps34 (Cell Signaling), APP (Calbiochem), sAPPα and giantin (Covance), APP C-terminal fragments (APP-Cter) (Invitrogen), LAMP1 and SNX3 (Abcam), RFP (Rockland), and Hrs (kind gift from G. Cesareni, University of Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy); a goat polyclonal antibody to Vps35 (Abcam); mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAb) to actin (Novus), Tsg101 (Abcam), beta amyloid 1–42 12F4 (Covance), sAPPα clone m3.2 (kind gift from P. Matthews, Nathan Kline Institute, NY, USA), APP N-terminus A4 22C11 (Millipore), Rab5, Rab7, and Synaptotagmin1 (Synaptic Systems), GAPDH (EnCor Biotech), GFP (Roche), Myc 9E10 (Invitrogen), EEA1 and GM130 (BD Transduction Laboratories), ubiquitin P4D1 (Santa Cruz), and LC3 4E12 (MBL); and a rat polyclonal antibody to LAMP1 (BD Pharmingen). Peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Biorad and fluorescent secondary antibodies (Alexa and Cyanin) were from Jackson Immunoresearch and Invitrogen..PI3-kinase activity was blocked with 100nM wortmannin (Invitrogen). To prevent autophagosome clearance, cells were treated with 50nM bafilomycin A1 (Waco) for 1h. γ-secretase was blocked for 24h with 10µM γ-secretase Inhibitor XXI, Compound E (both from Calbiochem).

Plasmids and RNA interference

Plasmids were kindly provided by the following sources: human Rab5Q79LGFP (M. Zerial, Dresden, Germany), Rab5Q79Lmyc (J. Gruenberg, Geneva, Switzerland), FYVE-FYVEGST and FYVE-FYVEGFP (H. Stenmark, Oslo, Norway), human Vps34RFP (N. Ktistakis, Cambridge, UK), and monomeric RFP (Roger Tsien, UCSD, California, USA). The APPGFP and APPMYC plasmids were constructed by excising the APP cDNA from APPRFP (derived from NM_201414.2) with SalI/ HindIII, and subcloning it into pEGFP-N3 (Clonetech) and pCMV5A (Stratagene), respectively. APP3RGFP was generated by quick mutagenesis on APPGFP with the following primer and its antisense: 5’-CACCTTGGTGATGCTGAgGAgGAgACAGTACACATCCATTC-3’. Human APPGFP and APP3RGFP lentiviruses were constructed by excising APPGFP and APP3RGFP from pEGFPN3 with NheI/ NotI and ligating the cDNAs into pCDH-CMV-MCSr (System Biosciences). Human APPmCherry and APP3RmCherry were constructed by SalI/NotI replacement of GFP in APPGFP, and APP3RGFP with a mCherry including SalI/NotI overhangs. For RNA interference in HeLa cells, we used an equal mix of the following predesigned human siRNA sequences (Qiagen): Vps34 (SI00040950/ SI00040971), Hrs (SI00288239/ SI02659650), Tsg101 (SI02655184/ SI02664522), SNX3 (S104309704/ S103150280) and Beclin1 (S100055573/ S100055580). Mouse Vps34-shRNA lentivectors were generated with the pSIH-H1 shRNA vector from System Biosciences. The control was pSIH1-H1-copGFP Luciferase shRNA, and the Vps34-shRNA targets were as follow: mVps34-1 shRNA, 5’-GTGGAGAGCAAACACCACAAGCTTGCTCG-3’; mVps34-2 shRNA, 5’- CCTGACCTGCCCAGGAATGCCCAAGTGGC-3’.

Lipid analysis

Phosphoinositide-enriched lipid fractions were extracted from frozen brain tissue samples (80–120 mg), deacylated, and analyzed by anion-exchange HPLC with suppressed conductivity detection as described 30,31 but with slight modification to the KOH gradient profile to better resolve PI4P and PI3P elution (Supplementary Fig. S1). Specifically, the elution was carried out in five stages; (1) a gradient change of 1.5 to 4mM KOH from injection time to 7 min postinjection, (2) 4 to 16mM from 7 to 12min post injection, (3) 16 to 25.75 mM from 12 to 35min postinjection, (4) 25.75 to 86mM from 35 to 60min postinjection and finally (5) 5min isoelectric elution with 86mM KOH. A portion of the same tissues used above was subjected to lipidomics analysis using LC-MS, as previously described 33.

Fluorescence microscopy

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30min and permeabilized with 0.05% saponin together with primary antibodies in PBS supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum. For the anti-APP-Cter staining, neurons were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min. For other stainings, neurons were permeabilized with 0.01% digitonin. For the labeling of PI3P with FYVE-FYVEGST, cells were fixed and incubated for 1h with purified FYVE-FYVEGST recombinant protein (20µg/mL final concentration), washed with PBS and labeled with a FITC-conjugated anti-GST antibody (Abcam). Coverslips were mounted in mowiol or DAPI-mowiol (Sigma) or ProLong Gold (Invitrogen). Images were acquired by confocal laser scanning microscopy (Zeiss LSM 700 and 510) and analyzed with Zeiss Zen and imageJ softwares.

Ultracryomicrotomy and immunogold Labeling

Hippocampal neurons at 15 DIV were fixed with a mixture of 2% (wt/vol) PFA and 0.125% (wt/vol) glutaraldehyde in 0.1M phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.4. Cell pellets were washed with PB, embedded in 10% (wt/vol) gelatin and infused in 2.3M sucrose 54. Mounted gelatin blocks were frozen in liquid nitrogen and ultrathin sections were prepared with an EM UC6 ultracryomicrotome (Leica). Ultrathin cryosections were collected with 2% (vol/vol) methylcellulose, 2.3M sucrose and single or double immunogold labeled with antibodies and protein A coupled to 5 or 10nm gold (PAG5 and PAG10; obtained from the Cell Microscopy Center of Utrecht University Hospital, Netherlands) as reported previously 54. Sections were observed under Philips CM-12 electron microscope (FEI; Eindhoven, The Netherlands) and photographed with a Gatan (4k x2.7k) digital camera (Gatan, Inc., Pleasanton, CA).

Protein biochemistry and immunoblotting

Total endosome fractions, comprising both early and late endosomal membranes, were generated as previously described 55. To detect ubiquitinated APP, HeLa cells were transiently transfected with human APPWTGFP or APP3RGFP and then lysed for 30 min at 4°C in immunoprecipitation buffer (0.5% NP-40, 500mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 20mM EDTA, 10mM NaF, 30mM sodium pyrophosphate decahydrate, 2 mM benzamidine, 1mM phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride, 1mM N-ethyl-maleimide, and a cocktail of protease inhibitors), centrifuged for 3min at 2,000 g, and supernatants were precleared with protein G-coupled beads (Invitrogen) prior to an incubation for 2h at 4°C with protein G-coupled beads and 2µg anti-GFP monoclonal antibody. For immunoprecipitation using mouse brain, tissue was collected and homogenized on ice with a Dounce homogenizer in immunoprecipitation buffer. After 30 min at 4°C, homogenates were centrifugated at 13.000 g for 5min. After pre-clearing, 500µl of lysate were incubated for 2h at 4°C with protein G-coupled beads and 10 µg anti-APP-Cter polyclonal antibody or 3µg anti-GFP monoclonal antibody (as a control). After washing the beads with immunoprecipitation buffer, proteins were eluated, separated on a Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen), and transferred by a semidry method on a nitrocellulose membrane. The latter was then probed sequentially with an anti-ubiquitin and anti-GFP antibody (after stripping). Quantification was made with Image J or the LAS4000 softwares. For all other immunoblots, cells were lysed for 30min at 4°C in RIPA buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails, centrifuged for 15min at 13.000 g, and proteins in the supernatant were processed for SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

ELISAs

Murine Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42, were measured from the medium of hippocampal cultures infected with a mix of shVps34 lentiviruses to monitor endogenous APP processing, and human Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42 and sAPPβ were quantified from the media of neurons infected with human APP-WT-GFP or APP-3R-GFP lentiviruses. The ELISA kits were from Invitrogen (Aβ) and Covance (sAPPβ), and the experiments were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, neurons were infected 7 days after plating, and the medium was harvested 7 days post-infection and supplemented with 0.25mg/ml Pefabloc SC 4-(2-Aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride, AEBSF) (Fluka Analytical). Each sample was then measured in duplicates.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using the Student’s t-test (for the comparison of two averages), the one-sample t test (for the comparison of one average to a normalized value where variability is lost), the one-way ANOVA test with post-hoc least significant difference or Tukey test (for the comparison of three or more averages). In Figure 1a, a one-tailed Student's t test was exceptionally used for the PI(4,5)P2 data, based on predictions from previously published work showing Aβ disrupts the metabolism of this lipid 31.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Etty Cortes at the New York Brain Bank for human brain preparation, Huasong Tian for generating the APPRFP construct, Akhil Bhalla for the neuronal culture and lentivirus production protocols, Laurence Abrami and Gisou Van Der Goot for the ubiquitin identification on transmembrane proteins protocol, and Harald Stenmark for the kind gift of FYVE-FYVEGST probe. We also acknowledge the EM facilities at the New York Structural Biology Center, and we thank Kelly McGrath for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health - R01 NS056049 (G.D.P.), P50 AG008702 (Shelanski, projects from G.D.P., B.D.M, and C.D.A.), R01 AG025161 (S.A.S.) and 2T32MH015174-35 (Z.L.), the Alzheimer’s Association (S.A.S. and G.D.P.), the Broitman Foundation (S.A.S.) and a fellowship from the Swiss National Science Foundation - PA00P3_124149 (Z.C.).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.M. and Z.C. designed, coordinated and carried out the bulk of the experiments. Z.M.L. carried out immunofluorescence experiments in neurons. R.B.C. designed and carried out the lipid biochemistry. R.L.W., K.S.P., and C.V. helped with the characterization of APP metabolites in neurons. C.D.A. helped with the preliminary protein analyses on human brains and with the LC3 immunofluorescence experiments. S.S. performed the immuno-electron microscopy experiments in neurons. E.M., Z.C., R.B.C., Z.M.L., R.L.W., C.V. and B.D.M. edited the manuscript. E.M., Z.C., R.B.C., B.D.M., S.A.S. and G.D.P. designed research. E.M., Z.C., S.A.S. and G.D.P. wrote the manuscript. G.D.P. and S.A.S. conceived the project, co-supervised the study and are co-senior authors.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTEREST

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Small SA, Gandy S. Sorting through the cell biology of Alzheimer's disease: intracellular pathways to pathogenesis. Neuron. 2006;52:15–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer's amyloid beta-peptide. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:101–112. doi: 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goate A, Hardy J. Twenty years of Alzheimer's disease-causing mutations. Journal of neurochemistry. 2012;120(Suppl 1):3–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajendran L, Annaert W. Membrane trafficking pathways in Alzheimer's disease. Traffic. 2012;13:759–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nixon RA. Endosome function and dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Strooper B, Vassar R, Golde T. The secretases: enzymes with therapeutic potential in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:99–107. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinoshita A, et al. Demonstration by FRET of BACE interaction with the amyloid precursor protein at the cell surface and in early endosomes. Journal of cell science. 2003;116:3339–3346. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajendran L, et al. Efficient inhibition of the Alzheimer's disease beta-secretase by membrane targeting. Science. 2008;320:520–523. doi: 10.1126/science.1156609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sannerud R, et al. ADP ribosylation factor 6 (ARF6) controls amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing by mediating the endosomal sorting of BACE1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:E559–E568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100745108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Refolo LM, Sambamurti K, Efthimiopoulos S, Pappolla MA, Robakis NK. Evidence that secretase cleavage of cell surface Alzheimer amyloid precursor occurs after normal endocytic internalization. Journal of neuroscience research. 1995;40:694–706. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490400515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehehalt R, Keller P, Haass C, Thiele C, Simons K. Amyloidogenic processing of the Alzheimer beta-amyloid precursor protein depends on lipid rafts. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:113–123. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grbovic OM, et al. Rab5-stimulated up-regulation of the endocytic pathway increases intracellular beta-cleaved amyloid precursor protein carboxyl-terminal fragment levels and Abeta production. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:31261–31268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304122200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carey RM, Balcz BA, Lopez-Coviella I, Slack BE. Inhibition of dynamin-dependent endocytosis increases shedding of the amyloid precursor protein ectodomain and reduces generation of amyloid beta protein. BMC Cell Biol. 2005;6:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-6-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cirrito JR, et al. Endocytosis is required for synaptic activity-dependent release of amyloid-beta in vivo. Neuron. 2008;58:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rajendran L, et al. Alzheimer's disease beta-amyloid peptides are released in association with exosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11172–11177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603838103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaether C, Schmitt S, Willem M, Haass C. Amyloid precursor protein and Notch intracellular domains are generated after transport of their precursors to the cell surface. Traffic. 2006;7:408–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cataldo AM, et al. Endocytic pathway abnormalities precede amyloid beta deposition in sporadic Alzheimer's disease and Down syndrome: differential effects of APOE genotype and presenilin mutations. The American journal of pathology. 2000;157:277–286. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64538-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takahashi RH, et al. Intraneuronal Alzheimer abeta42 accumulates in multivesicular bodies and is associated with synaptic pathology. The American journal of pathology. 2002;161:1869–1879. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64463-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takahashi RH, et al. Oligomerization of Alzheimer's beta-amyloid within processes and synapses of cultured neurons and brain. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:3592–3599. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5167-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Small SA, et al. Model-guided microarray implicates the retromer complex in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:909–919. doi: 10.1002/ana.20667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muhammad A, et al. Retromer deficiency observed in Alzheimer's disease causes hippocampal dysfunction, neurodegeneration, and Abeta accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7327–7332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802545105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lane RF, et al. Vps10 family proteins and the retromer complex in aging-related neurodegeneration and diabetes. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32:14080–14086. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3359-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhalla A, et al. The location and trafficking routes of the neuronal retromer and its role in amyloid precursor protein transport. Neurobiology of disease. 2012;47:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qiang L, et al. Directed conversion of Alzheimer's disease patient skin fibroblasts into functional neurons. Cell. 2011;146:359–371. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25.Israel MA, et al. Probing sporadic and familial Alzheimer's disease using induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2012;482:216–220. doi: 10.1038/nature10821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Paolo G, De Camilli P. Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature. 2006;443:651–657. doi: 10.1038/nature05185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raiborg C, Schink KO, Stenmark H. Class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and its catalytic product PtdIns3P in regulation of endocytic membrane traffic. The FEBS journal. 2013 doi: 10.1111/febs.12116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaeger PA, Wyss-Coray T. Beclin 1 complex in autophagy and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:1181–1184. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dall'Armi C, Devereaux KA, Di Paolo G. The role of lipids in the control of autophagy. Current biology : CB. 2013;23:R33–R45. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nasuhoglu C, et al. Nonradioactive analysis of phosphatidylinositides and other anionic phospholipids by anion-exchange high-performance liquid chromatography with suppressed conductivity detection. Anal Biochem. 2002;301:243–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berman DE, et al. Oligomeric amyloid-beta peptide disrupts phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate metabolism. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:547–554. doi: 10.1038/nn.2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McIntire LB, et al. Reduction of synaptojanin 1 ameliorates synaptic and behavioral impairments in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. The Journal of neuroscience. 2012;32:15271–15276. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2034-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chan RB, et al. Comparative lipidomic analysis of mouse and human brain with Alzheimer disease. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:2678–2688. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.274142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gillooly DJ, et al. Localization of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate in yeast and mammalian cells. Embo J. 2000;19:4577–4588. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burgos PV, et al. Sorting of the Alzheimer's disease amyloid precursor protein mediated by the AP-4 complex. Dev Cell. 2010;18:425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nixon RA. Autophagy, amyloidogenesis and Alzheimer disease. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:4081–4091. doi: 10.1242/jcs.019265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou X, et al. Deletion of PIK3C3/Vps34 in sensory neurons causes rapid neurodegeneration by disrupting the endosomal but not the autophagic pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9424–9429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914725107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henne WM, Buchkovich NJ, Emr SD. The ESCRT Pathway. Dev Cell. 2011;21:77–91. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raiborg C, Stenmark H. The ESCRT machinery in endosomal sorting of ubiquitylated membrane proteins. Nature. 2009;458:445–452. doi: 10.1038/nature07961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stenmark H, et al. Inhibition of rab5 GTPase activity stimulates membrane fusion in endocytosis. The EMBO journal. 1994;13:1287–1296. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choy RW, Cheng Z, Schekman R. Amyloid precursor protein (APP) traffics from the cell surface via endosomes for amyloid beta (Abeta) production in the trans-Golgi network. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:E2077–E2082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208635109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pons V, et al. Hrs and SNX3 functions in sorting and membrane invagination within multivesicular bodies. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e214. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haglund K, Di Fiore PP, Dikic I. Distinct monoubiquitin signals in receptor endocytosis. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:598–603. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta-Rossi N, et al. Monoubiquitination and endocytosis direct gamma-secretase cleavage of activated Notch receptor. The Journal of cell biology. 2004;166:73–83. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200310098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watanabe T, Hikichi Y, Willuweit A, Shintani Y, Horiguchi T. FBL2 regulates amyloid precursor protein (APP) metabolism by promoting ubiquitination-dependent APP degradation and inhibition of APP endocytosis. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32:3352–3365. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5659-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Christoforidis S, et al. Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinases are Rab5 effectors. Nature cell biology. 1999;1:249–252. doi: 10.1038/12075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.El Ayadi A, Stieren ES, Barral JM, Boehning D. Ubiquilin-1 regulates amyloid precursor protein maturation and degradation by stimulating K63-linked polyubiquitination of lysine 688. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:13416–13421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206786109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Strooper B, Annaert W. Novel research horizons for presenilins and gamma-secretases in cell biology and disease. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2010;26:235–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Small SA. Retromer sorting: a pathogenic pathway in late-onset Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:323–328. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2007.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pritchard SM, Dolan PJ, Vitkus A, Johnson GV. The toxicity of tau in Alzheimer disease: turnover, targets and potential therapeutics. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:1621–1635. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01273.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Landman N, et al. Presenilin mutations linked to familial Alzheimer's disease cause an imbalance in phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19524–19529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604954103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oliveira TG, et al. Phospholipase d2 ablation ameliorates Alzheimer's disease-linked synaptic dysfunction and cognitive deficits. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:16419–16428. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3317-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Di Paolo G, Kim TW. Linking lipids to Alzheimer's disease: cholesterol and beyond. Nature reviews. Neuroscience. 2011;12:284–296. doi: 10.1038/nrn3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raposo G, et al. Accumulation of major histocompatibility complex class II molecules in mast cell secretory granules and their release upon degranulation. Molecular biology of the cell. 1997;8:2631–2645. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.12.2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morel E, Gruenberg J. The p11/S100A10 light chain of annexin A2 is dispensable for annexin A2 association to endosomes and functions in endosomal transport. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.