Abstract

Unlike DNA, in addition to the 2′-OH group, uracil nucleobase and its modifications play essential roles in structure and function diversities of non-coding RNAs. Non-canonical U•U base pair is ubiquitous in non-coding RNAs, which are highly diversified. However, it is not completely clear how uracil plays the diversifing roles. To investigate and compare the uracil in U-A and U•U base pairs, we have decided to probe them with a selenium atom by synthesizing the novel 4-Se-uridine (SeU) phosphoramidite and Se-nucleobase-modified RNAs (SeU-RNAs), where the exo-4-oxygen of uracil is replaced by selenium. Our crystal structure studies of U-A and U•U pairs reveal that the native and Se-derivatized structures are virtually identical, and both U-A and U•U pairs can accommodate large Se atoms. Our thermostability and crystal structure studies indicate that the weakened H-bonding in U-A pair may be compensated by the base stacking, and that the stacking of the trans-Hoogsteen U•U pairs may stabilize RNA duplex and its junction. Our result confirms that the hydrogen bond (O4…H-C5) of the Hoogsteen pair is weak. Using the Se atom probe, our Se-functionalization studies reveal more insights into the U•U interaction and U-participation in structure and function diversification of nucleic acids.

INTRODUCTION

Unlike natural DNA, which merely stores genetic information in cells (1), natural RNA is highly diversified in structure and function. Because of the RNA diversity, RNA plays essential functions in cells and expands complexity of living systems by serving as genetic information carrier, catalyst and regulator (2–10). Recently, tremendous functional RNAs have been discovered as non-coding RNAs (ncRNA), such as ribozymes, riboswitches, small interfering RNA (siRNA), microRNA (miRNA), small nuclear RNA (snRNA) and RNAs regulating biological pathways. ncRNAs can control gene expressions selectively through transcription and translation regulations (11,12), participate in chromatin silencing and remodeling (13), regulate the retroviruses activity (14), catalyze biochemical reactions (15,16), recognize metabolites (17), as well as facilitate gene function study and drug discovery (18,19). ncRNAs play highly specific roles by folding into various 3D structures and binding specifically with other molecules or ligands (such as proteins and metabolites), which may trigger cascades of biological events.

However, considering the similar chemical structures of nuclei acid building blocks (such as almost the same nucleobases in RNA and DNA), it is striking that RNA with the extra 2′-OH is able to establish much more diversified structures and functions than DNA (20,21). In addition to the 2′-OH group, it appears that the RNA modifications and non-canonical base pairings are the two major strategies to overcome the structural homogeneity limit caused by the four similar nucleobases and to achieve huge diversities in both structure and function (22–24). Especially, uracil nucleobase can form multiple non-canonical base pairings and play essential roles in diversifying RNA structure and function. Non-canonical U•U base pair is ubiquitous in ncRNA, and Watson–Crick U-A pair can often be replaced with U-G wobble pair without significant duplex destablization, which increases structure and function diversity of ncRNAs. U•U pairs are often observed in RNA duplex joinction and loops (25–27), whereas U-A pair is normally not formed at these places. Replacing U-A pair in duplex with U•U pair significantly destablizes the duplex structure. It is not completely clear how uracil plays the diversifying roles in these base pairs to achieve the structure and function diversity. To investigate and compare the uracil roles played in these non-canonical and canonical pairs, we have decided to probe the U•U and U-A pairs with a Se atom, where the exo-4-oxygen of uracil is replaced by selenium.

Though 4-Se-uridine was synthesized over three decades ago (28,29), it has not been incorporated into RNAs because of the synthetic challenges. Recently, our successes on the synthesis and biophysical studies of the Se-nucleobase modifications (30–35) have encouraged us to overcome the SeU-RNA synthesis challenge, meet the urgent needs in ncRNA investigation and probe U-A and U•U pairs by a Se atom. Herein, we report the first synthesis of the 4-Se-uridine phosphoramidite (SeU) and the corresponding SeU-RNAs by replacing 4-oxygen with selenium. We have found that this Se-modification does not cause significant perturbation and that the native and modified structures are virtually identical. We also found that via the stacking and hydrogen bonding, the uracil nucleobase interacts differently in RNA duplex and duplex junction. Moreover, the accommodation of the larger selenium atom by both U-A and U•U pairs implies the RNA flexibility. Our studies suggest that by presenting their different faces and edges, uracil and uridine are capable of diversifing structure and function of ncRNAs. Furthermore, this Se-modified uridine offers the Se-RNAs with additional UV absorption (λmax: 370 nm; ε: 1.30 × 104 M−1cm−1). Excitingly, after a single-oxygen atom replacement with selenium, we have observed for the first time the color RNAs (light yellow) as well as color RNA crystals (dark yellow). The color property of the SeU-RNAs is unique and has great potentials in RNA visualization, detection, spectroscopic study and crystallography of RNAs and protein-RNA complexes and interactions, demonstrating the usefulness of selenium-derivatized nucleic acids (SeNA) (36,37) in structural biology. In addition, both the anomalous phasing and molecular replacement approaches result in the identical crystal structures. Our new method provides a unique atomic tool for probing structure and function of ncRNAs and their protein complexes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis of the 4-Se-uridine phosphoramidite

3-(1-((2R,3S,4S,5R)-5-((bis(4-methoxyphenyl)(phenyl)methoxy)methyl)-3-(tert-butyldimethyl-silyloxy)-4-hydroxy-tetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyrimidin-4-ylselanyl)propanenitrile

To a dry THF solution (10 ml) of the starting material compound (1, 1.34 g, 2 mmol), 4,4′-dimethylamino-pyridine (24.5 mg, 0.2 mmol) and triethylamine (0.56 ml, 4 mmol) under argon, the dry tetrahydrofuran (THF) solution (10 ml) of 2,4,6-trisopropylbenzenessulfonyl chloride (906 mg, 3.0 mmol) was added dropwisely. The reaction was stirred for 1 h before it is finished (monitor by thin layer chromatography (TLC), 5% methanol in dichloromethane). At the same time, the NaBH4 suspension (250 mg of NaBH4 in 3 ml of EtOH) was injected into a flask containing di(2-cyanoethyl) diselenide [(NCCH2CH2Se)2, 0.3 ml, d = 1.8 g/ml, 2.0 mmol] and THF (10 ml) in an ice bath with argon. The yellow color of the diselenide disappeared in ∼15 min, giving an almost colorless suspension of sodium selenide (NCCH2CH2SeNa). Then, the reacted solution of compound 1 was slowly injected into this selenide solution. After the selenium incorporation was completed in 45 min (monitored on TLC, 5% MeOH in CH2Cl2, product Rf = 0.60), water (100 ml) was added to the reaction flask. The solution was adjusted to pH 7–8 using CH3COOH (10%) and was then extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 100 ml). The organic phases were combined, washed with NaCl (sat., 100 ml), dried over MgSO4 (s) for 30 min and evaporated to minimum volume under reduced pressure. The crude product was then dissolved in methylene chloride (5 ml) and purified on a silica gel column equilibrated with hexanes/methylene chloride (1:1). The column was eluded with a gradient of methylene chloride (CH2Cl2, 0.5%, 1% and 2% MeOH in CH2Cl2, 300 ml each). After the collected fraction evaporation and dry under high vacuum, pure compound 2 was obtained as a slightly yellow foam product (1.27 g, 81% yield). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 0.21 (s, 3H, CH3), 0.38 (s, 3H, CH3), 0.95 (s, 6H, 2× CH3), 2.31-2.37 (m, 1H, H-2′), 3.00 (dd, J = 6.5 and 6.7 Hz, 2H, CH2-Se), 3.37-3.41 (m, 2H, CH2-CN), 3.50-3.52 (m, 2H, 1H-5′), 3.81 (s, 6H, 2× OCH3), 4.17–4.22 (m, 1H, H-3′), 4.31 (s, 1H, 3′-OH), 4.40–4.50 (m, 1H, H-4′), 5.78 (s, 1H, H-1′), 5.90 (d, 1H, J = 6.8 Hz, H-5), 6.8–6.90 (m, 4H, aromatic), 7.20–7.46 (m, 9H, aromatic), 8.31 (d, 1H, J = 6.8 Hz, H-6). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: −4.30, −4.40 (CH3), 18.1 (CH2-CN), 19.0 (CH2-CH2-CN), 20.5 [(CH3)2C(t-Bu)], 25.9 (CH3), 55.3 (OCH3), 68.7 (C-3′), 76.4 (C-2′), 83.1 (C-4′), 91.0 (C-1′), 106.0 (C-5), 118.8 (CN), 113.3, 127.1, 128.0, 128.2, 130.1, 135.0, 135.3, 144.2, 158.7 (Ar-C), 140.4 (C-6), 153.3 (C-2), 175.0 (C-4). HRMS (ESI-TOF): molecular formula, C39H49N3O7SeSi; [M+H]+: 778.2413 (calc.778.2426).

(2R,3S,4S,5R)-2-((bis(4-methoxyphenyl)(phenyl)methoxy)methyl)-4-(tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy)-5-(4-(2-cyanoethylselanyl)-2-oxopyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)-tetrahydrofuran-3-yl-2-cyanoethyl diisopropylphosphoramidite

To the flask (25 ml) containing 2 (453 mg, 0.68 mmol) under argon, dry methylene chloride (2.5 ml), N,N-diisopropylethylamine (0.17 ml, 1.03 mmol, 1.5 eq.), and 2-cyanoethyl N,N-diisopropyl-chlorophosphoramidite (195 mg, 0.83 mmol, 1.2 eq.) were added sequentially (3). The reaction mixture was stirred at −10°C in an ice-salt bath under argon for 10 min, followed by removal of the bath. The reaction was completed in 2 h at room temperature, generating a mixture of two diastereomers (indicated by TLC, 5% MeOH in CH2Cl2, product Rf = 0.63 and 0.68). The reaction was then quenched with NaHCO3 (5 ml, sat.) and stirred for 5 min, followed by the extraction with CH2Cl2 (3 × 8 ml). The combined organic layer was washed with NaCl (10 ml, sat.) and dried over MgSO4 (s) for 30 min, followed by filtration. The solvent was then evaporated under reduced pressure, and the crude product was re-dissolved in CH2Cl2 (2 ml). This solution was added drop-wise to cold petroleum ether (or hexane) (200 ml) under vigorous stirring, generating a white precipitate. The petroleum ether layer was decanted. The crude product was re-dissolved again in CH2Cl2 (2 ml) and then loaded on Al2O3 column (neutral) that was equilibrated with CH2Cl2/Hexanes (1:1). The column was eluded with a gradient of methylene chloride and ethyl acetate [CH2Cl2 to CH2Cl2/EtOAc (7:3)]. After solvent evaporation and dry over high vacuum, the compound 3 (612 mg) was obtained as a white foamy product (92% yield). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, two sets of signals from a mixture of two diastereomers) δ: 0.2–0.4 (m,12H, 4 × CH3), 0.85–1.20 [m, 36H, 8 × CH3-ipr and 4× Si(CH3)], 2.30–2.38 and 2.70–2.82 (2× m, 4H, 2× H-2′), 2.34 and 2.64 (2× t, J = 6.4 Hz, 4H, 2× O-CH2-CH2-CN), 3.00–3.04 (m, 4H, 2× Se-CH2-CH2-CN), 3.32–3.44 (m, 6H, 2× H-5′, 2× Se-CH2), 3.52–3.64 (m, 8H, 4× CH-ipr, 2× O-CH2-CH2-CN), 3.73–3.84 (m, 2H, 2× H-5′), 3.82 and 3.83 (2× s, 12H, 4× OCH3), 4.12–4.35 (m, 2H, 2× H-3′), 4.43–4.48 (m, 2H, 2× H-4′), 5.70–5.90 (m, 4H, 2× H-5 and 2× H-1′), 6.83–6.88 (m, 8H, aromatic), 7.27–7.43 (m, 18H, aromatic), 8.30 and 8.39 (2× s, 2H, 2× H-6). HRMS (ESI-TOF): molecular formula, C48H64N5O8PSeSi; [M + H]+: 978.3479 (calc. 978.3505).

Synthesis of the SeU-RNAs

All the RNA oligonucleotides were chemically synthesized in 1.0 μmol scale on solid phase. The ultra-mild RNA phosphoramidites protected with 2′-TBDMS were used (Glen Research). The concentration of the SeU-phosphoramidite was 0.08 M in acetonitrile, compared with the regular ones (0.1 M). Coupling was carried out using 5-(benzylmercapto)-1H-tetrazole solution (0.25 M) in acetonitrile with 12 min coupling time for both native and Se-modified phosphoramidites. Three percent trichloroacetic acid in methylene chloride was used for the 5′-detritylation. Synthesis was performed on control-pore glass (CPG-500) immobilized with the appropriate nucleoside through a succinate linker. All oligonucleotides were prepared in dimethoxy trityl (DMTr)-on form. After synthesis, the RNAs were cleaved from the solid support and fully deprotected by 0.05 M K2CO3 (methanol solution) for 8 h at room temperature, followed by neutralization, evaporation and the treatment of tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF) solution (1 M in THF) for overnight. After desalting and HPLC purification, the 5′-DMTr group was removed by 3% aqueous solution of trichloroacetic acid, and the solution was neutralized to pH 7.0 with a freshly made triethylammonium acetate (TEAAc) buffer and precipitated with NaCl (final concentration: 0.3 M before ethanol addition) and ethanol (3 volumes). The ethanol suspension was placed at −80°C for 1 h, followed by centrifugation to collect the RNAs.

HPLC analysis and purification

The RNA oligonucleotides were analyzed and purified by reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) in DMTr-on form. After the TBAF desilylation and desalting with sephadex G-25, HPLC purification was carried out using a 21.2 × 250 mm Zorbax, RX-C8 column at a flow rate of 6 ml/min. Buffer A consisted of 10 mM TEAAc (pH 7.1), whereas buffer B contained 50% acetonitrile and 10 mM TEAAc (pH 7.1). Similarly, the HPLC analysis was performed on a Zorbax SB-C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm) at a flow of 1.0 ml/min using the same buffer system. The DMTr-on oligonucleotides were eluded in a 20-min linear gradient of 100% buffer A to 100% buffer B. The HPLC analysis for both DMTr-on and DMTr-off oligonucleotides were carried out with up to 60% of buffer B in a linear gradient in the same period of time. The collected fractions were lyophilized, and the purified RNAs were re-dissolved in water for the detritylation and precipitation steps.

Thermodenaturation of the SeU-RNAs

Solutions of the duplex RNAs (1 or 2 μM) were prepared by dissolving the purified RNAs in sodium phosphate [10 mM (pH 6.5)] buffer containing 100 mM NaCl. The solutions were heated to 75°C for 3 min, then cooled down slowly to room temperature and stored at 4°C overnight before Tm measurement. Before thermal denaturation, the Se-RNA samples were bubbled with argon for 5 min. Each denaturizing curves were acquired at 260 nm by heating and cooling from 5 to 70°C for four times in a rate of 0.5°C/min, using Cary-300 UV-Visible spectrometer equipped with temperature controller system.

Se-RNA crystallization and diffraction data collection

The purified RNA oligonucleotides (1 mM) were heated to 70°C for 2 min and cooled down slowly to room temperature. Both native buffer and Nucleic Acid Mini Screen Kit (Hampton Research) were applied to screen the crystallization conditions at different temperatures using the hanging drop method by vapor diffusion (1 µl of RNA and 1 µl of buffer). Thirty percent glycerol, PEG 400 or the perfluoropolyether was used as a cryoprotectant during the crystal smounting, and data collection was taken under the liquid nitrogen stream at 99°K. The Se-RNA crystal data were collected at beam line X12B and X12C in NSLS, Brookhaven National Laboratory. A number of crystals were screened to find the ones with strong anomalous scattering at the K-edge absorption of selenium. The distance of the detector to the crystals was set to 150 mm. The radiation wavelength at 0.9795 Å was chosen for diffraction data collection and selenium single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) phasing. The crystals were exposed for 10 s per image with 1° oscillation, and a total of 180 images were taken for each data set. All data were processed using HKL2000 and DENZO/SCALEPACK (38).

Structure determination and refinement

The structures of Se-RNAs were solved by both SAD with HKL2MAP and molecular replacement with Phaser (39), followed by the refinement with Refmac. Both SAD phasing and molecular replacement led to the same crystal structure. The refinement protocol includes simulated annealing, positional refinement, restrained B-factor refinement and bulk solvent correction. The stereo-chemical topology and geometrical restrain parameters of DNA/RNA (40) have been applied. The topologies and parameters for the uridine modified with selenium (US) were constructed and applied. After several cycles of refinement, a number of highly ordered waters were added. Finally, the occupancies of selenium were adjusted. Cross-validation (41) with a 5–10% test set was monitored during the refinement. The σA-weighted maps (42) of the (2 m|Fo| - D|Fc|) and the difference (m|Fo| - D|Fc|) density maps were computed and used throughout the model building.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

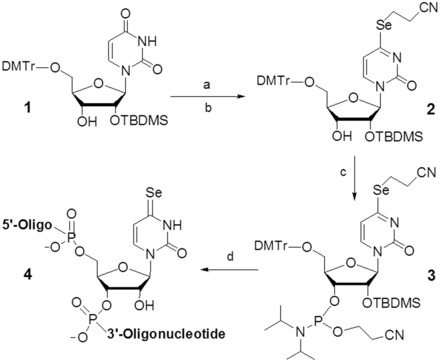

Synthesis of the 4-Se-uridine (SeU) phosphoramidite

We have developed a facile strategy to synthesize the Se-phosphoramidite. As showed in Scheme 1, our synthesis started from the partially protected 2′-TBDMS-5′-trityl-uridine (1). To simplify the synthesis, we used a bulky reagent (2,4,6-triisopropylbenzenesulfonyl chloride, TIBS-Cl) to selectively activate position 4, thus avoiding the protection and deprotection steps of the 3′-hydroxyl group. Without purifying the activated intermediate, the selenium functionality was introduced by substituting TIBS group at position 4 with 2-cyanoethylselenide in the yield of 81%. Sodium 2-cyanoethylselenide was generated by the reduction of di-(2-cyanoethyl) diselenide with NaBH4 in ethanol solution (30). This protected Se-functionality is compatible with the solid-phase synthesis and can be removed by weak base treatment (K2CO3 in methanol). Finally, the 4-Se-uridine derivative (2) was converted to the corresponding phosphoramidite (3) in 92% yield. The analysis data are shown in the supporting information (Supplementary Figures S1–S7).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of SeU-phosphoramidite (3) and SeU-RNAs (4). Reagents and conditions: (a) TIBS-Cl, 4,4′-dimethylamino-pyridine, CH2Cl2, room temperature; (b) (NCCH2CH2Se)2/NaBH4, EtOH; (c) 2-cyanoethyl N,N-diisopropylchloro-phosphoramidite and N,N-diisopropylethylamine in CH2Cl2; (d) the solid-phase synthesis. TIBS-Cl: 2,4,6-(triisopropylbenzene)sulfonyl chloride.

Synthesis of the SeU-RNAs

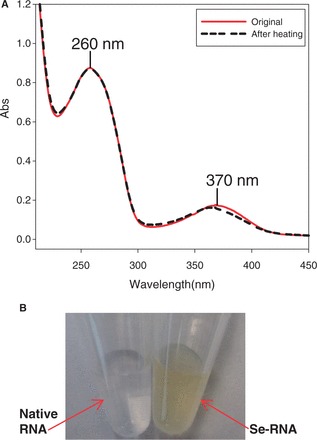

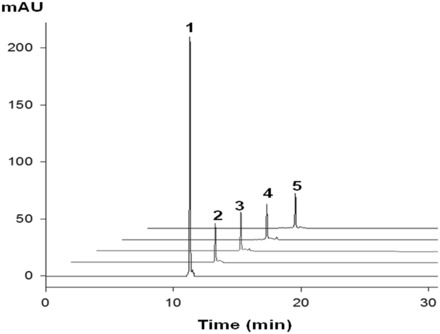

The ultramild phosphoramidites, where the base-labile protecting groups can be deprotected with a weak base (K2CO3 in methanol) (30,32,33,35,43), were used because the 4-Se-functionality is sensitive to strong base cleavage (such as ammonia, causing deselenization). We found that this Se-modified phosphoramidite is compatible with the longer coupling time (12 min), I2 oxidation and trichloroacetic acid treatment without deselenization. In the case of RNAs containing multiple guanosine residues, phenoxyacetic anhydride (Pac2O) instead of acetic anhydride was used in the capping step to avoid the acetylation of guanosine, which is difficult to remove under the mild deprotecting conditions (K2CO3 in methanol). All Se-RNAs were synthesized in DMTr-on form, followed by cleavage and deprotection with 0.05 M methanol solution of K2CO3. After the deprotection, the solution was carefully neutralized with 1 M HCl and evaporated to dryness. Then the 2′-TBDMS groups were removed by treating with 1 M TBAF solution in THF at room temperature overnight. After desilylation and desalting, a typical HPLC profile of the crude Se-RNAs is shown in Supplementary Figure S8, which indicates a high coupling yield of the Se-uridine phosphoramidite (96%), compared with incorporation of the non-modified phosphoramidites. After desalting with Sephadex-G25 matrix, the pure Se-RNAs were obtained by RP-HPLC purification, followed by the mild detritylation (44). Several SeU-RNAs containing Watson–Crick U-A and Hoogsteen U•U pairs were synthesized, purified and characterized (Table 1 and Supplementary Figures S8 and S9). Excitingly, we observed for the first time that the RNA with the single Se-atom substitution is visible and has yellow color. UV-vis spectroscopic study indicated the Se-RNA with λmax at 260 and 370 nm (Figure 1) resulted from the native nucleobases and SeU, respectively. The color RNAs can be used as potential probes for many biochemical and biomedical applications. We also found that the Se-RNA crystals are yellow color, indicating this Se-derivatization is especially useful for the crystallization screening of RNAs and protein-RNA complexes. The color is due to the ease of the electron delocalization on the nucleobase after the selenium derivatization, thereby red-shifting the spectrum significantly by over 100 nm. Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that this Se-functionality is relatively stable. After heating the Se-RNA at 70°C for 8 h, no significant decomposition was observed, indicated by UV and HPLC analyses (Figures 1A and 2).

Table 1.

MALDI-TOF-MS Analysis of SeU-RNA

| Entry | Se-RNAs | Measured (calcd) m/z |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5′-U-SeU-CGCG-3′ (C56H71N20O41P5Se) | [M + H]+: 1915.4 (1915.2) |

| 2 | 5′-G-SeU-GUACAC-3′ (C76H95N30O53P7Se) | [M + H]+: 2573.3 (2573.3) |

| 3 | 5′-GUG-SeU-ACAC-3′ (C76H95N30O53P7Se) | [M + H]+: 2573.5 (2573.3) |

| 4 | 5′-AUGG-SeU-GCUC-3′ (C85H106N32O62P8Se) | [M + H]+: 2895.3 (2895.7) |

| 5 | 5′-CGCGAA-SeU-UCGCG-3′ (C114H144N46O81P11Se) | [M + H]+: 3873.3 (3874.5) |

| 6 | 5′-CGCGAAU-SeU-CGCG-3′ (C114H144N46O81P11Se) | [M + H]+: 3874.0 (3874.3) |

| 7 | 5′-U-SeU-AUAUAUAUAUAA-3′ (C133H162N49O95P13Se) | [M + H]+: 4449.7 (4449.6) |

| 8 | 5′-AA-SeU-A(2′-SeMe-U)AUAUAUAUU-3′ (C134H164N49O94P13Se2) | [M + H]+: 4526.4 (4526.4) |

| 9 | 5′-GG-SeU-AUUGCGGUACC-3′ (C133H165N52O97P13Se) | [M + H]+: 4526.4 (4526.7) |

| 10 | 5′-A-SeU-CACCUCCUUA-3′ (C111H141N38O82P11Se) | [M + H]+: 3740.8 (3740.2) |

| 11 | U-SeU-AGCUAGCU (C94H117N34O69P9Se) | [M + H]+: 3186.2 (3185.9) |

| 12 | U-SeU-CGCGAUCGCG (C113H142N43O83P11Se) | [M + H]+: 3851.7 (3851.3) |

| 13 | U-SeU-CAUGUGACC (C103H129N37O76P10Se) | [M + H]+: 3489.8 (3490.4) |

Figure 1.

The UV spectra and color of the SeU-RNA. (A) red line (λmax = 260 and 370 nm): UV spectrum of the SeU-RNA (5′-G-SeU-GUACAC-3′) without heating; black broken line (λmax = 260 and 367 nm): UV spectrum of the SeU-RNA after heating at 70°C for 8 h; (B) the SeU-RNA (yellow, 1.0 mM) and the corresponding native RNA (colorless, 1.0 mM).

Figure 2.

Thermal stability analysis of SeU-RNA (5′-G-SeU-GUACAC-3′). HPLC profile 1 and 2 (without heating of the Se-RNA) monitored at 260 and 370 nm, respectively. HPLC profile 3, 4 and 5 (monitored at 370 nm) were analysis of the Se-RNA heated at 70°C for 2, 5 and 8 h, respectively.

Determination of extinction coefficient of SeU ( )

)

To determine the extinction coefficient of 4-Se-uridine residue (SeU) by comparing with the native nucleotide, we synthesized and purified the SeUMP and 5′-SeUU-3′. Their HPLC profiles are presented in Figure 3. The HPLC assistance, which removes and minimizes the interference of impurities, allows accurate measurement of the extinction coefficients (43). Our experimental results indicate that SeU residue absorbs at both 260 and 370 nm (Figure 3A). The absorption ratio at these two wavelengths is 5.71, calculated on the basis of the HPLC peak areas. As the extinction coefficient is proportional to the absorption, Equation (1) is deduced. In addition, from the HPLC profile (Figure 3B) of 5′-SeUU-3′, the ratio between the absorption at 260 nm (contributed by both native U and SeU) and 370 nm (only by SeU) is determined as 0.920. Thus, Equation (2) is deduced. As the extinction coefficient of native U at 260 nm ( = 9.66 × 103 M−1cm−1) is known (45), we calculated the extinction coefficient of SeU at 370 nm (

= 9.66 × 103 M−1cm−1) is known (45), we calculated the extinction coefficient of SeU at 370 nm ( ) and 260 nm (

) and 260 nm ( ) are 13.0 and 2.28 × 103 M−1cm−1, respectively.

) are 13.0 and 2.28 × 103 M−1cm−1, respectively.

| (1) |

| (2) |

Figure 3.

Calculation of  and

and  via RP-HPLC analysis. (A) HPLC profile of 3′-SeUMP at 260 nm (solid line) and 370 nm (dash line). (B) HPLC profile of 5′-SeUU-3′ dimer at 260 nm (solid line) and 370 nm (dash line). The samples (3′-SeUMP and 5′-SeUU-3′) were analyzed on a Welchrom XB-C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μ) at a flow of 1.0 ml/min and with a linear gradient of 5–50% B in 20 min, with a retention time of 10.3 and 13.6 min, respectively. Buffer A: 10 mM TEAAc (pH 7.1); B: 50% acetonitrile in 10 mM TEAAc (pH 7.1).

via RP-HPLC analysis. (A) HPLC profile of 3′-SeUMP at 260 nm (solid line) and 370 nm (dash line). (B) HPLC profile of 5′-SeUU-3′ dimer at 260 nm (solid line) and 370 nm (dash line). The samples (3′-SeUMP and 5′-SeUU-3′) were analyzed on a Welchrom XB-C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μ) at a flow of 1.0 ml/min and with a linear gradient of 5–50% B in 20 min, with a retention time of 10.3 and 13.6 min, respectively. Buffer A: 10 mM TEAAc (pH 7.1); B: 50% acetonitrile in 10 mM TEAAc (pH 7.1).

Thermodenaturation study

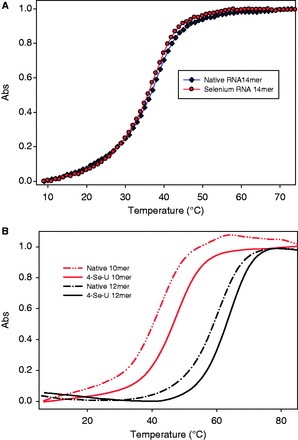

The rationales of using a Se atom to probe the U-A and U•U base pairs are that selenium, a large-size atom, can probably strengthen the stacking interaction and is a poorer hydrogen-bond acceptor (30,32,33) that can likely weaken the hydrogen-bond (H-bond) interaction. The polarizable and large Se atom with delocalizable electrons can increase the stacking interaction by narrowing the gap between the stacked nucleobases, which is observed in our crystal structure presented in this work. Furthermore, the increase of the stacking interaction by this Se atomic probe is consistent with the computational study of the Se-modified thymidine in DNA duplex (46). Thus, the Se-atom probe that alters the stacking and H-bonding interactions may provide novel insights into the base pairs. To investigate the RNA duplex recognition and stability, we carried out the UV-melting study with RNAs containing the 4-Se-uracil in duplexes or in duplex junctions (or overhang regions). Typical curves of Se-RNA melting-temperatures (Tm) are showed in Figure 4, and all the Tm data are summarized in Table 2, compared with the corresponding native RNA duplexes. When the Se-atom probe is introduced to the uracil in RNA duplexes, no significant Tm differences between the native and Se-modified duplexes were observed (entry 1–8 in Table 2), and the free energy (ΔG) differences with the corresponding natives were almost zero. This suggests that the Se-atom probe in RNA duplex regions may not cause significant perturbation in duplex stability. As selenium is a poor H-bond acceptor, it is anticipated that the Se-mediated H-bond in the U-A pair is weak. The zero (or very small) free energy difference between the native and Se-modified RNA duplexes also indicates that the stability increase via the stronger stacking compensates the stability decrease caused by the weaker H-bonding. This observation reveals that the modified U-A base-pair can maintain a fine balance between the stacking and H-bonding interactions.

Figure 4.

(A) Normalized Tm curve of Se-RNA (5′-UUA-SeU-AUAUAUAUAA-3′)2, compared with the corresponding native RNA. The Se-RNA (circle line): Tm = 37.3 ± 0.5°C; the native (diamond line): Tm = 38.0 ± 0.3°C. (B) Normalized Tm profiles of Se-RNA 10mer (5′-rU-SeU-AGCUAGCU-3′)2 and 12mer (5′-U-SeU-CGCGAUCGCG-3′)2, compared with their corresponding natives. The native RNA-10mer (gray dash-dot line): Tm = 42.2 ± 0.2°C; the Se-RNA 10mer (gray solid line): Tm = 47.1 ± 0.3°C; the native RNA 12mer (black dash-dot line): Tm = 59.4 ± 0.3°C; the Se-RNA 12mer (black solid line): Tm = 63.2 ± 0.3°C.

Table 2.

UV-melting temperatures of SeU-RNAs

| Entry | Modified region | RNA sequences | Tm (°C) | ΔTm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (5′-rUUAUAUAUAUAUAA-3′)2 | 38.0 ± 0.3 | ||

| 2 | Duplex | (5′-rUUA-SeU-AUAUAUAUAA-3′)2 | 37.3 ± 0.5 | −0.7 |

| 3 | (5′-rGGUAUUGCGGUACC-3′)2 | 45.0 ± 0.4 | ||

| 4 | Duplex | (5′-rGG-SeU-AUUGCGGUACC-3′)2 | 44.2 ± 0.3 | −0.8 |

| 5 | (5′-rCGCGAAUUCGCG-3′)2 | 39.4 ± 0.4 | ||

| 6 | Duplex | (5′-rCGCGAAU-SeU-CGCG-3′)2 | 39.0 ± 0.3 | −0.4 |

| 7 | 5′-AUCACCUCCUUA-3′ | 43.2 ± 0.3 | ||

| 3′-UAGUGGAGGAAU-5′ | ||||

| 8 | Duplex | 5′-A-SeU-CACCUCCUUA-3′ | 42.8 ± 0.4 | −0.4 |

| 3′-U–A–GUGGAGGAAU-5′ | ||||

| 9 | (5′-UUAGCUAGCU-3′)2 | 42.2 ± 0.2 | ||

| 10 | Duplex junction | (5′-U-SeU-AGCUAGCU-3′)2 | 47.1 ± 0.3 | +4.9 |

| 11 | (5′-UUCGCGAUCGCG-3′)2 | 59.4 ± 0.3 | ||

| 12 | Duplex junction | (5′-U-SeU-CGCGAUCGCG-3′)2 | 63.2 ± 0.3 | +3.8 |

| 13 | 5′-UUCAUGUGACC-3′ | 48.2 ± 0.3 | ||

| 3′—–GUACACUGGUU-5′ | ||||

| 14 | Duplex junction | 5′-U-SeU-CAUGUGACC-3′ | 49.9 ± 0.4 | +1.7 |

| 3′——–GUACACUGGUU-5′ |

It is reported that a U•U pair is less stable comparing with a U-G or C-A mispair in a RNA duplex (33,47). In RNA duplex junctions and loops, however, the two consecutive U•U pairs are more stable than the two consecutive A-A pairs (48). Thus, the Se-atom probe is used to investigate the non-canonical U•U pair, and we chose and modified the RNAs forming RNA duplex and UU junction (Table 2). The UV-thermal denaturation study was carried out, and the melting-temperatures (Tm) of the Se-RNAs and their corresponding natives are summarized in Table 2 (entry 9–14). Excitingly, when the atomic probe is introduced to the RNA duplex junctions, the melting temperatures increased by 1.5–2.4°C per Se-modification of these RNA duplexes. Consistently, the free energy (ΔG) calculation indicates that each Se atom contributed additional stabilization (0.4–0.8 kcal/mol) to the stability of the RNA duplexes. This increased RNA duplex stability is attributed to the increased stacking interaction of SeU on the duplex ends; the support from the high-resolution structure data is presented later. Via the Se-atom probe, the UV-melting study of the duplex RNAs containing the UU junction indicates that the uracil stacking contributes significantly to RNA duplex stability.

Crystallization, diffraction data collection and crystal structure determination

To investigate the Se-nucleobase modification and its structural property, we have crystallized two Se-RNA sequences [hexamer (5′-rU-SeU-CGCG-3′)2 with overhangs and octamer (5′-rGUG-SeU-ACAC-3′)2 with a perfect duplex]. Crystals of both Se-RNA sequences were formed in 2–5 days at room temperature (25°C) with the Hampton nucleic acid mini-screen kit (total 24 buffers with broad conditions). Excitingly, all crystals of both Se-RNAs had strong yellow or dark yellow color because of the selenium modification (Figures 5 and 6). The Se-RNA hexamer formed crystals in 22 of 24 buffers using the kit, whereas the corresponding native RNA formed crystals only in 4 of 24 buffers (in 3 weeks) using the kit. Most of these Se-RNA crystals (one example shown in Figure 5) diffracted very well, up to 1.3 Å resolution (the orthorhombic space group, C2221). Similarly, the Se-RNA octamer formed crystals in 22 of 24 buffers using the same kit, and these crystals (examples shown in Figure 6) could diffract up to 2.5 Å resolution (the rhombohedral space group, R32). In contrast, the corresponding native (5′-rGUGUACAC-3′)2 did not crystallize under any conditions over several weeks, which is consistent with the literature (49). The native octamer (5′-rGUGUACAC-3′)2 is difficult to crystalize, and its structure has not been reported in literature. Finally, several high-quality crystals from these two Se-RNAs were mounted and cryo-protected for the diffraction data collection. The structures were determined using the best data sets and diffractions collected from the crystals grown in buffer No.10 [10% MPD, 40 mM Na Cacodylate (pH 6.0), 12 mM Spermine tetra-HCl, 12 mM NaCl and 80 mM KCl] for the Se-hexamer and No.12 [10% MPD, 40 mM Na Cacodylate (pH 6.0), 12 mM Spermine tetra-HCl, 80 mM KCl and 20 mM BaCl2] for the Se-octamer. The statistic data of the structural analysis are summarized in Table 3, and the determined Se-RNA structures are presented in Figures 5 and 6.

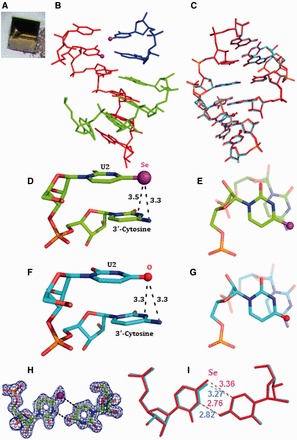

Figure 5.

The yellow crystal and structures of the 4-Se-U RNA hexamer, (5′-U-SeU-CGCG-3′)2. The purple and red balls represent Se and O atoms, respectively. (A) The picture of the yellow Se-RNA crystal (0.1 × 0.1 × 0.1 mm). (B) Structure of the Se-RNA duplex containing the Se-RNA hexamer (in red), the base-paired CGCG (in green) and the U•U-paired U-SeU (in blue). (C) Superimposition of the Se-modified structure (in red; PDB ID: 3HGA; 1.30 Å resolution) and the native structure (in cyan; PDB ID: 1OSU; 1.40 Å resolution), the rmsd value is 0.09 Å. (D) Se-modified U2 stacks on its 3′-cytosine; the distance between the Se atom and exo-N4 of 3′-cytosine is 3.3 Å; the distance between the Se atom and C4 of 3′-cytosine is 3.5 Å. (E) is the top view of (D). (F) Native U2 stacks on its 3′-cytosine; the distance between the O atom and exo-N4 of 3′-cytosine is 3.3 Å; the distance between the O atom and C4 of 3′-cytosine is 3.3 Å. (G) is the top view of (F). (H) Electron density map (2Fo-Fc) and model of the SeU•U pair at the level of 1.0 σ. (I) Superimposition of SeU•U pair (in red) with native U•U pair (in cyan); the H-bond lengths are indicated individually.

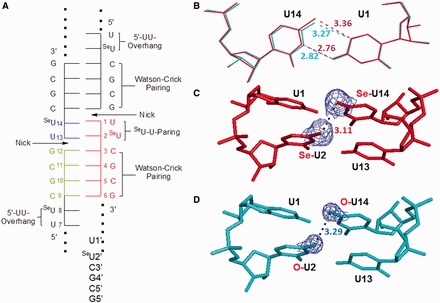

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram and local structures of the native and modified U•U pairs in overhang regions (or duplex junctions). (A) Schematic diagram of the RNA duplex with five strands, the nicks, SeU•U pairs and normal Watson–Crick C-G pairs. (B) Superimposition comparison of SeU14•U1 (in red) with native U14•U1 pair (in cyan); the numbers represent the H-bond lengths (Å). (C) The stacking of two SeU•U pairs with the distance (3.11 Å) between the two neighbor Se atoms in the modified U14 and U2. (D) The stacking of two native U•U pairs with the distance (3.29 Å) between the two neighbor O atoms in native U14 and U2. The 2Fo-Fc maps of Se-4 and O-4 are showed.

Table 3.

Diffraction data collection and refinement statistics of the Se-RNA structures

| Structure (PDB ID) | U-SeU-CGCG (3HGA) | GUG-SeU-ACAC (4IQS) |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | Se-Hexamer | Se-Octamer |

| Space group | C2221 | R32 |

| Cell dimensions: a,b,c (Å) | 30.255, 34.079, 28.931 | 47.006, 47.006, 354.105 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 120 |

| Resolution range, Å (last shell) | 50.00–1.30 (1.32–1.30) | 50.0–2.60 (2.69–2.60) |

| Unique reflections | 3773 (162) | 8915 (846) |

| Completeness% | 95.9 (90.0) | 99.2 (95.8) |

| Rmerge% | 4.5 (26.1) | 5.3 (35.8) |

| I/σ(I) | 40.5 (1.2) | 35.9 (1.0) |

| Redundancy | 11.7 (4.2) | 10.0 (6.1) |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution range, Å | 22.62–1.30 | 31.73.0–2.60 |

| Rwork% | 18.9 | 19.4 |

| Rfree% | 22.5 | 25.8 |

| Number of reflections | 3586 | 4776 |

| Number of atoms | ||

| Nucleic acid (single) | 157 | 1002 |

| Heavy atoms and ion | 1 Se | 6 Se |

| Water | 42 | 0 |

| R.m.s. deviations | ||

| Bond length, Å | 0.005 | 0.008 |

| Bond angle, ° | 0.931 | 1.846 |

Rmerge =

Structures of 4-Se-derivatized RNAs

The structure of the Se-RNA hexamer (Figure 5) revealed formation of the right-handed Watson–Crick duplex (Supplementary Table S1) and Hoogsteen base pairs. The structures determined via SAD and molecular replacement approaches are identical. The Se-modified structure (PDB ID: 3HGA; 1.30 Å resolution) and the corresponding native structure (PDB ID: 1OSU; 1.40 Å resolution) (50) are virtually identical as well. They can superimpose on each other perfectly well (Figure 5C) with the RMSD as 0.09 Å, indicating the fine structure isomorphism. Moreover, the electron delocalization of the large Se atom on the uracil may facilitate the nucleobase stacking interaction, also supported by the computational study of the Se-modified nucleobase (46). Furthermore, Se atom is 0.43 Å larger than O, and the distances between U2 4-exo-Se and the 3′-cytosine atoms (N3, exo-N4, C4 and C5) are similar to the corresponding native distances between U2 4-exo-O and the 3′-cytosine atoms (Figure 5D and E); the distances between the 4-Se or 4-O atom and the 3′-C atoms are also displayed. Thus, the comparison of the Se-modified and native structures (Figure 5D-I) suggests that the Se-nucleobase may better stack on the 3′-cytosine than the native nucleobase. The stronger stacking interaction can rigidify the local conformation and strengthen the RNA duplexes, which are consistent with the stronger duplex stability in the presence of the UU overhang (or duplex junction; Table 2). These results are also consistent with the faster crystal growth after the selenium modification. Similar to the corresponding native structure (50), two SeU•U pairs (Hoogsteen pair) have been observed in the Se-RNA (Figure 5F and G). In the Se-modified and native structures, both SeU•U and U•U pairs participate in formation of a pseudo-fiber and long duplex through the overhang Hoogsteen-base pairs. The 5′-UU sequence allows the RNAs (both the Se-modified and native ones) infinitely stacking and elongating along the 21 screw axis in the crystals with nicks on the 5′-end of each 5′-U(SeU). This 5′-U-SeU sequence forms the two symmetrical SeU•U base pairs, which is virtually identical to the native U•U pair (Figure 5G). Namely, this junction sequence forms the two symmetrical SeU•U base pairs, which glue the RNA duplexes together in a head-to-tail linear fashion.

The results of our crystal structure study are consistent with the UV-melting study. The 5′-UU of one RNA molecule (e.g. the red one in Figure 6A) forms two U•U pairs with the second RNA molecule (the blue one), whereas its consecutive CGCG sequence forms regular Watson–Crick base pairs with the third RNA molecule (the green one). As showed in Figure 5F, the SeU•U pair displays a conventional hydrogen bond between O4 of the native uracil (U1) and N3 of the Se-uracil (U14) and an unusual C-H…Se hydrogen bond between C5 of native U and Se4 of Se-U, through the Hoogsteen edge of native U and the Watson–Crick edge of Se-U. These interactions result in a trans-Hoogsteen U•U pair (Figure 5F). Compared with the native structure, the substitution of the uridine 4-oxygen with a selenium atom does not change the structure significantly (Figure 5C), suggesting that the Hoogsteen U•U pair has space available at 4-position of the Watson–Crick edge. A slight shift (0.09 Å) on the Se-modified nucleobase is observed (Figure 6B). The Hoogsteen C-H…Se (or O) hydrogen bond (bond length: 3.36 Å in the Se case), between C5 of native U and Se4 of Se-U (the corresponding native H-bond: 3.27 Å; Figure 6B), is still retained. Because selenium atom (1.16 Å in atomic radius) is 0.43 Å larger than oxygen (0.73 Å in atomic radius), it is surprising to find the nucleobase shift only by 0.09 Å to accommodate the big selenium atom, confirming that the native hydrogen bond (O4…H-C5) of the Hoogsteen pair is weak. Thus, the large Se atom probe indicates that the Hoogsteen H-bond is less important in the U•U pairing. This also suggests that the trans-Hoogsteen pair can tolerate a larger substitution and that the Hoogsteen pair is not rigid, which gives the duplex junction sufficient flexibility. Moreover, it is counterintuitive that the distance (3.11 Å) between these two big neighboring 4-Se atoms (Figure 6C) is even smaller (by 0.18 Å) than the native distance (3.29 Å) between these two small O atoms (Figure 6D), implying the enhanced stacking interactions between these two U•U pairs. Using electron-rich selenium as the atomic probe, our structural result suggests the strong electron delocalization and stacking interaction between these two U•U pairs. The structure study provides new insights into the Hoogsteen U•U pair and the uracil-mediated interactions in ncRNAs.

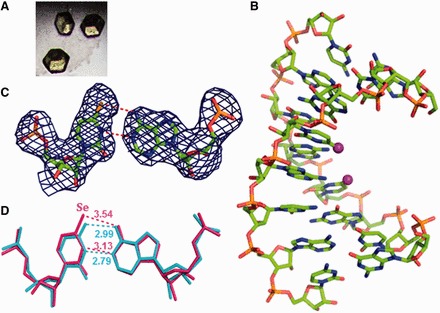

The Se-octamer structure (Figure 7), where the two Se atoms point to the major groove, reveals formation of the SeU-A pair and the typical right-handed A-form duplex by the Se-RNA (Supplementary Table S2). Moreover, we have superimposed the structures of SeU-A (or SeU4-A13 pair) and U2-A15 pair (Figure 7D), as the corresponding native structure is not available (from literature or us) for direct comparison. This comparison of the base pair structures has demonstrated that the Se-modified and native U-A pairs are similar. The major difference is the slight shift of the SeU nucleobase to accommodate the large selenium atom, revealing the flexibility of RNA duplex structure. The distance between SeU4 exo-Se4 and A13 exo-N6 is 3.54 Å, which was increased from the original 2.99 Å. Considering that the atomic size of Se is 0.43 Å larger than that of O and that a typical H-bond length is 2.8–3.2 Å, this distance (3.54 Å) suggests a weak hydrogen bond after the Se-modification. On the other hand, the polarizable and large Se atom with delocalizable electrons may facilitate the base stacking interaction, supported by the narrower base-pair gap and the computational study of the Se-nucleobase-modified DNA (46). Using the Se atom probe, we found that the increased stacking interaction can compensate the loss of the H-bond interaction, which is consistent with the virtually identical duplex stability after the Se-modification (Table 2). Moreover, most of the 2′-hydroxyl groups are involved in the H-bonding interactions with its 3′-sugar ring oxygen (O4′) or 3′-phosphate oxygen, which restrains the conformations of the sugar-phosphate backbone, thereby facilitating the intramolecular interaction and reducing molecular dynamics. The Se-RNA crystallization is consistent with the Se-enhanced base stacking and conformation rigidification. In the crystal lattice, the duplexes are stacked on the top of each other in a head-to-tail fashion and three Se-RNA duplexes present in an asymmetric unit, where the three duplexes are virtually identical (r.m.s < 0.1 Å). Chain A and B are showed in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The yellow crystals and structures of the 4-Se-U RNA octamer, (5′-GUG-SeU-ACAC-3′)2. The Se atoms are labeled as purple balls. (A) Crystal image. (B) The Se-RNA duplex structure (PDB ID: 4IQS; 2.75 Å resolution). (C) Electron density map (2Fo-Fc) and model of the SeU-A pair at the level of 1.0 σ. (D) Superimposition of SeU-A pair (in pink) with native U2-A15 pair (in cyan); the H-bond lengths are indicated individually.

Furthermore, X-ray crystallography is one of the most powerful methodologies for structure and function studies of RNAs and their complexes with ligands, including protein-RNA complexes and RNA-small molecule complexes, at the atomic resolution. However, owing to the difficulties in crystallization and phasing (phase determination or phase problem), progress in RNA crystallography is limited, especially in the ncRNA structure study. Inspired by the protein Se-derivatization, multi-wavelength anomalous dispersion phasing and SAD phasing (51–55), our laboratory has pioneered SeNA (36,37), which has great potential as a general strategy for RNA X-ray crystallography (37). This research work on the synthesis and structure studies of the 4-Se-uridine RNAs has further demonstrated that the selenium modification is a useful approach for structural biology, as the Se-functionalization can facilitate phase determination, crystallization, RNA color and atomic probing.

CONCLUSION

To probe uracil-mediated interactions and base-pairs with a single selenium atom, we have synthesized the 4-Se-uridine phosphoramidite and Se-RNAs. Our thermostability and structure studies indicate that the modified and native structures are virtually identical, that the H-bonding decrease in U-A pair can be compensated by the base-stacking increase, and that the uracil stacking in duplex junction may increase duplex thermostability. We also found that the stacking interaction of the two trans-Hoogsteen U•U pairs is the main contributor to the duplex junction stability, whereas the Hoogsteen H-bond is weak. Moreover, the accommodation of larger Se atoms in uracil by both U-A and U•U pairs implies the RNA flexibility. Using the Se atom probe, our studies confirm that uracil is capable of interacting in multiple modes, thereby diversifying U•U and U-A pairs in structure and function. Our thermodynamic and structural studies have also demonstrated that this Se-modification can facilitate the nucleobase stacking interaction and potential crystal growth without significant perturbation. Furthermore, this Se-modification generates color RNA for the first time by single atom replacement, and it shifts the uridine UV spectrum over 100 nm (SeU λmax: 370 nm; ε: 1.30 × 104 M−1cm−1). This color property is useful for RNA-protein co-crystallization, RNA visualization, detection and spectroscopic study. This work provides a new strategy for crystallization, phasing, structure and function studies of ncRNAs and protein-RNA complexes.

ACCESSION NUMBERS

3HGA, 4IQS

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the mail-in program and PXrr in Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL). The National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS) at BNL is funded by NIH’s National Center for Research Resources and DOE’s Office of Biological and Environmental Research.

FUNDING

NIH [R01GM095881] and Georgia Cancer Coalition (GCC) Distinguished Cancer Clinicians and Scientists. Funding for open access charge: NIH [R01GM095881] and Georgia Cancer Coalition (GCC) Distinguished Cancer Clinicians and Scientists.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Watson JD, Crick FH. Genetical implications of the structure of deoxyribonucleic acid. Nature. 1953;171:964–967. doi: 10.1038/171964b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Imai M, Richardson MA, Ikegami N, Shatkin AJ, Furuichi Y. Molecular cloning of double-stranded RNA virus genomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1983;80:373–377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.2.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bass BL, Cech TR. Specific interaction between the self-splicing RNA of Tetrahymena and its guanosine substrate: implications for biological catalysis by RNA. Nature. 1984;308:820–826. doi: 10.1038/308820a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cate JH, Gooding AR, Podell E, Zhou K, Golden BL, Kundrot CE, Cech TR, Doudna JA. Crystal structure of a group I ribozyme domain: principles of RNA packing. Science. 1996;273:1678–1685. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5282.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lohse PA, Szostak JW. Ribozyme-catalysed amino-acid transfer reactions. Nature. 1996;381:442–444. doi: 10.1038/381442a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheah MT, Wachter A, Sudarsan N, Breaker RR. Control of alternative RNA splicing and gene expression by eukaryotic riboswitches. Nature. 2007;447:497–500. doi: 10.1038/nature05769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradshaw N, Neher SB, Booth DS, Walter P. Signal sequences activate the catalytic switch of SRP RNA. Science. 2009;323:127–130. doi: 10.1126/science.1165971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lincoln TA, Joyce GF. Self-sustained replication of an RNA enzyme. Science. 2009;323:1229–1232. doi: 10.1126/science.1167856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai MC, Manor O, Wan Y, Mosammaparast N, Wang JK, Lan F, Shi Y, Segal E, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNA as modular scaffold of histone modification complexes. Science. 2010;329:689–693. doi: 10.1126/science.1192002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weill L, James L, Ulryck N, Chamond N, Herbreteau CH, Ohlmann T, Sargueil B. A new type of IRES within gag coding region recruits three initiation complexes on HIV-2 genomic RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:1367–1381. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JT. Epigenetic regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Science. 2012;338:1435–1439. doi: 10.1126/science.1231776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rinn JL, Chang HY. Genome regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012;81:145–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051410-092902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rinn JL, Kertesz M, Wang JK, Squazzo SL, Xu X, Brugmann SA, Goodnough LH, Helms JA, Farnham PJ, Segal E, et al. Functional demarcation of active and silent chromatin domains in human HOX loci by noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2007;129:1311–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coley W, Kehn-Hall K, Van Duyne R, Kashanchi F. Novel HIV-1 therapeutics through targeting altered host cell pathways. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2009;9:1369–1382. doi: 10.1517/14712590903257781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein DJ, Ferre-D'Amare AR. Structural basis of glmS ribozyme activation by glucosamine-6-phosphate. Science. 2006;313:1752–1756. doi: 10.1126/science.1129666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ke A, Zhou K, Ding F, Cate JH, Doudna JA. A conformational switch controls hepatitis delta virus ribozyme catalysis. Nature. 2004;429:201–205. doi: 10.1038/nature02522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rottiers V, Naar AM. MicroRNAs in metabolism and metabolic disorders. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:239–250. doi: 10.1038/nrm3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qureshi IA, Mehler MF. Emerging roles of non-coding RNAs in brain evolution, development, plasticity and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012;13:528–541. doi: 10.1038/nrn3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esteller M. Non-coding RNAs in human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:861–874. doi: 10.1038/nrg3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilbert W. The RNA World. Nature. 1986;319:618. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gesteland RF, Cech TR, Atkins JF. The RNA World: The Nature of Modern RNA Suggests a Prebiotic RNA. 3rd edn. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Czerwoniec A, Dunin-Horkawicz S, Purta E, Kaminska KH, Kasprzak JM, Bujnicki JM, Grosjean H, Rother K. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D118–D121. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ. Origins and Mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell. 2009;136:642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phizicky EM, Alfonzo JD. Do all modifications benefit all tRNAs? FEBS Lett. 2010;584:265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michel F, Jacquier A, Dujon B. Comparison of fungal mitochondrial introns reveals extensive homologies in RNA secondary structure. Biochimie. 1982;64:867–881. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(82)80349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davies RW, Waring RB, Ray JA, Brown TA, Scazzocchio C. Making ends meet: a model for RNA splicing in fungal mitochondria. Nature. 1982;300:719–724. doi: 10.1038/300719a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michel F, Netter P, Xu MQ, Shub DA. Mechanism of 3′ splice site selection by the catalytic core of the sunY intron of bacteriophage T4: the role of a novel base-pairing interaction in group I introns. Genes Dev. 1990;4:777–788. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.5.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wise DS, Townsend LB. Synthesis of the selenopyrimidine nucleosides 2-seleno- and 4-selenouridine J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1972;9:1461–1465. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shiue CY, Chu SH. A facile synthesis of 1-beta-D-arabinofuranosyl-2-seleno- and -4-selenouracil and related compounds. J. Org. Chem. 1975;40:2971–2974. doi: 10.1021/jo00908a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salon J, Sheng J, Jiang J, Chen G, Caton-Williams J, Huang Z. Oxygen replacement with selenium at the thymidine 4-position for the Se base pairing and crystal structure studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:4862–4863. doi: 10.1021/ja0680919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caton-Williams J, Huang Z. Synthesis and DNA-polymerase incorporation of colored 4-selenothymidine triphosphate for polymerase recognition and DNA visualization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2008;47:1723–1725. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hassan AE, Sheng J, Zhang W, Huang Z. High fidelity of base pairing by 2-selenothymidine in DNA.J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:2120–2121. doi: 10.1021/ja909330m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun H, Sheng J, Hassan AE, Jiang S, Gan J, Huang Z. Novel RNA base pair with higher specificity using single selenium atom. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:5171–5179. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheng J, Zhang W, Hassan AE, Gan J, Soares AS, Geng S, Ren Y, Huang Z. Hydrogen bond formation between the naturally modified nucleobase and phosphate backbone. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:8111–8118. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang W, Hassan AE, Huang Z. Synthesis of novel Di-Se-containing thymidine and Se-DNAs for structure and function studies. Sci. China Chem. 2013;56:273–278. doi: 10.1007/s11426-012-4800-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carrasco N, Ginsburg D, Du Q, Huang Z. Synthesis of selenium-derivatized nucleosides and oligonucleotides for X-ray crystallography. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2001;20:1723–1734. doi: 10.1081/NCN-100105907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin L, Sheng J, Huang Z. Nucleic acid X-ray crystallography via direct selenium derivatization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:4591–4602. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15020k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Meth. Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parkinson G, Vojtechovsky J, Clowney L, Brunger AT, Berman HM. New parameters for the refinement of nucleic acid-containing structures. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1996;52:57–64. doi: 10.1107/S0907444995011115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brunger AT. Free R value: a novel statistical quantity for assessing the accuracy of crystal structures. Nature. 1992;355:472–475. doi: 10.1038/355472a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Read RJ. Improved Fourier coefficients for maps using phases from partial structures with errors. Acta. Cryst. A. 1986;42:140–149. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salon J, Jiang J, Sheng J, Gerlits OO, Huang Z. Derivatization of DNAs with selenium at 6-position of guanine for function and crystal structure studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:7009–7018. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salon J, Zhang B, Huang Z. Mild detritylation of nucleic acid hydroxyl groups by warming-up. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2011;30:271–279. doi: 10.1080/15257770.2011.580640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cavaluzzi MJ, Borer PN. Revised UV extinction coefficients for nucleoside-5′-monophosphates and unpaired DNA and RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Christofferson A, Zhao L, Sun H, Huang Z, Huang N. Theoretical studies of the base pair fidelity of selenium-modified DNA.J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:10041–10048. doi: 10.1021/jp204204x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kierzek R, Burkard ME, Turner DH. Thermodynamics of single mismatches in RNA duplexes. Biochemistry. 1999;38:14214–14223. doi: 10.1021/bi991186l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.SantaLucia J, Jr, Kierzek R, Turner DH. Stabilities of consecutive A.C, C.C, G.G, U.C, and U.U mismatches in RNA internal loops: evidence for stable hydrogen-bonded U.U and C.C.+ pairs. Biochemistry. 1991;30:8242–8251. doi: 10.1021/bi00247a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wahl MC, Ramakrishnan B, Ban C, Chen X, Sundaralingam M. RNA - synthesis, purification and crystallization. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1996;52:668–675. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996002788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wahl MC, Rao ST, Sundaralingam M. The structure of r(UUCGCG) has a 5′-UU-overhang exhibiting Hoogsteen-like trans U.U base pairs. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1996;3:24–31. doi: 10.1038/nsb0196-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hendrickson WA. Determination of macromolecular structures from anomalous diffraction of synchrotron radiation. Science. 1991;254:51–58. doi: 10.1126/science.1925561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hendrickson WA. Synchrotron crystallography. Trends. Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:637–643. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01721-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang W, Hendrickson WA, Crouch RJ, Satow Y. Structure of ribonuclease H phased at 2 A resolution by MAD analysis of the selenomethionyl protein. Science. 1990;249:1398–1405. doi: 10.1126/science.2169648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deacon AM, Ealick SE. Selenium-based MAD phasing: setting the sites on larger structures. Structure. 1999;7:R161–R166. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Girard E, Chantalat L, Vicat J, Kahn R. Gd-HPDO3A, a complex to obtain high-phasing-power heavy-atom derivatives for SAD and MAD experiments: results with tetragonal hen egg-white lysozyme. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2002;58:1–9. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901016444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.