Abstract

A mild and efficient isomerization/protonation sequence involving an appropriately functionalized indole precursor to generate a wide variety of pyran-fused indoles utilizing cooperative catalysis between cationic iridium (III) and bismuth triflate has been developed. Three distinct cyclization manifolds lead to bioactive scaffolds that can be obtained in good yields. In addition, N-substituted indoles can be synthesized enantioselectively via an oxocarbenium• chiral phosphate counterion strategy.

Keywords: catalysis, pyran, methodology, cooperative catalysis, indole

Tetrahydropyrans (THPs) are important heterocycles found in biologically active natural products and small molecules.[1] There are several established methods to construct THPs including hetero-Diels-Alder cycloadditions,[2] intramolecular conjugate additions,[3] or ring-closing metathesis.[4] A major approach for pyran synthesis involves the condensation of an aldehyde with a homoallylic partner with subsequent C–C bond formation (Prins cyclization, Figure 1).[5] This general Prins strategy has been proven to be efficient for the synthesis of biologically active small molecules[6] as well as a key tactic in the construction of complex natural products.[7] Yet while the Prins reaction is convergent in nature, recognized drawbacks to the typical conditions for this transformation include: a) the use of strong Lewis or Brønsted acids to generate the requisite oxocarbenium ion 1, b) the need for reactive carbonyl compounds (e.g., aldehydes) and elevated temperatures to drive the reaction to completion, and c) the control of the stereochemical outcome and exchange of reaction substituents from potentially competing oxonia-Cope pathways.[8]

Figure 1.

Tandem isomerization cyclization

An alternative approach to the Prins manifold that potentially circumvents these issues associated with promoting dehydration and subsequent oxocarbenium formation is a transition metal-catalyzed isomerization/protonation sequence involving an appropriately functionalized precursor (Figure 1). Efficient single flask operations involving alkene isomerization steps have been utilized in Friedel-Crafts reactions[9], as well as asymmetric Claisen rearrangements.[10] Our strategy to access Prins-type oxocarbenium intermediates without the need for strong dehydrating conditions involves the isomerization of allyl ether 2 to enol ether 3. The enol ether can then be protonated under mild acidic conditions to provide oxocarbenium 1 in the presence of a suitable alkene nucleophile with subsequent C–C bond formation. Protonations of enol ethers have also been used independently by Rychnovsky and Dobbs to promote Prins cyclizations with vinyl and allyl silanes.[11] Notably, the construction of pyran 4 would be possible at ambient temperatures and without the use of carbonyl functional groups.

As a proof of concept for this Prins process, we crafted our approach around the indole core as the requisite nucleophilic alkene component (Figure 1, Nuc). Utilizing indoles in this process would intersect intermediates in the oxa-Pictet-Spengler reaction,[12] which has been used to generate many biologically relevant oxacycles,[13] but can often suffer from the same limitations as the Prins cyclization. To leverage our substrate design and maximize potential compound library synthesis, the appendage of an allyl group on the N-, C2- and C3- position of the indole enables the synthesis of three different types of pyran-fused indole scaffolds (Figure 1).[14]

Substituted indoles are abundant in biologically active compounds and promising pharmaceuticals[15] For example, the core structure from the type 1 process is found in the anti-inflammatory drug etodolac.[16] The lead compound HCV-371, a potent hepatitis C NS5A polymerase inhibitor discovered by high through put screening and chemical optimization, also contains this substitution.[17] Indoles from type 2 have also been studied for their inhibition of NS5A polymerase.[18] Finally, the heterocycles from a type 3 variant of the proposed cyclization have been studied for their potential anti-depressant and anti-tumor properties.[19] Despite the significant interest in these compounds for biological applications, an efficient and unified approach to obtain these products is lacking.[20] Herein, we describe the development of a tandem catalytic isomerization Prins-type cyclization for the efficient construction of three types of pyran-fused indoles geared toward bioactive compound library development.[21, 6a]

We initially sought to achieve this reaction in a stepwise manner by first isomerizing allyl ether 5 to enol ether 6 and subsequently adding an acid source to facilitate cyclization to pyran 7. We began our studies by first exploring conditions for the isomerization of allyl ether 5 to the intermediate enol ether 6. After examining several different conditions, iridium catalyst [IrH2(THF)2(PPh2Me)2)]PF6, used previously by Miyaura to convert allyl ethers to E-vinyl ethers, was determined to be the most effective catalyst for the isomerization.[22] With the isomerization conditions identified, both Brønsted acids and metal triflates were evaluated for their ability to catalyze the efficient cyclization of 5 to pyran 7 (Table 1). Metal triflates can be employed as “hidden” acid catalysts which circumvent the difficulties of using small amounts of strong Brønsted acids.[23] Acids such as TMSOTf, camphorsulfonic acid (CSA), MeSO3H and Yb(OTf)3 did not completely promote cyclization to pyran 7. Lewis acids such as InCl3 and FeCl3 were tried with FeCl3 promoting nearly full conversion to 7 (90:10, entry 5).[24] In contrast, the addition of Bi(OTf)3 to the reaction after the isomerization resulted in full conversion to pyran 7 in high yield (70%, entry 7). In particular, Bi(OTf)3 has been used as a convenient and mild source of triflic acid in the presence of water[25] and has been proven to be effective in catalyzing Prins-type cyclizations.[26] To assess whether Bi(OTf)3 is a TfOH source in this process, a control experiment with 2,6-di-tert-butyl pyridine (DTBP) as an additive was performed. With the addition of this hindered base, only low conversion to the pyran and mostly enol ether was observed (entry 10).

Table 1.

Screening of acid sources

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Acid source | 6: 7 | Yield (%)[c] |

| 1 | TMSOTf | 40:60 | n/a |

| 2 | CSA | 73:27 | n/a |

| 3 | MeSO3H | 54:46 | n/a |

| 4 | InCl3 | 94:6 | n/a |

| 5 | FeCl3 | 10:90 | n/a |

| 6 | Yb(OTf)3 | 35:65 | n/a |

| 7 | Bi(OTf)3 | 0:100 | 70 |

| 8 | Bi(OTf)3[d] | 0:100 | 70 |

| 9 | TfOH | 0:100 | 65 |

| 10 | Bi(OTf)3[e] | 90:10 | n/a |

1 mol % [IrH2(THF)2(PPh2Me)2)]PF6 in THF (0.1M) b.1 mol % acid source

Isolated yield after column chromatography

Simultaneous addition of both catalysts: reaction time decreased from 12 h to 2 h.

2,6-(t-Bu)2-pyridine (10 mol %) added.

Given our interest in the area of cooperative catalysis,[27] we were interested if the simultaneous addition of the metal triflate and the iridium complex directly to the reaction mixture containing 5 would provide a simple protocol for this transformation and possibly increase the activity of either/both catalysts. Cooperative catalysis has been successfully employed with transition metals and Brønsted acids,[28] and recent independent reports by Rueping and Xiao describe the combination of iridium complexes and Brønsted acids to facilitate reductions of imines.[29] Our cascade isomerization/protonation strategy seemed a prime candidate to apply this catalyst combination for the construction of C–C bonds. To test this hypothesis, indole 5 was simultaneously subjected to [IrH2(THF)2(PPh2Me)2]PF6 and Bi(OTf)3 at 1 mol % each (entry 6): the reaction proceeded to 100% conversion in only 2 h (vs. 12 h for initial alkene isomeration with Ir(III) alone, then Bi(OTf)3). We attribute the decrease in reaction time due to Brønsted acid acceleration of the isomerization, thereby leading a cooperative/synergistic affect for this system.

We then directed our attention toward the synthesis of various indole-fused heterocycles to investigate if the cooperative/synergistic effect observed could be applied for the three types of indoles discussed above. Beginning with the case type 1 scaffold, in which the allyl ether is appended at the C3 position, the reactions proceeded in high yields with a variety of different products formed (compounds 8–13, Table 2).

Table 2.

Substrate scope[a]

|

1 mol % [IrH2(THF)2(PPh2Me)2)]PF6 in THF (0.1M) 1 mol % Bi(OTf)3 added simultaneously

diastereomeric ratios determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy (500 MHz).

6 mol% of iridium catalyst was needed for full conversion,

5-Substituted indoles (e.g. 9–10) are compatible with the cooperative catalysis conditions, including products such as 10 containing an aryl bromide functionality which can serve as a handle for additional functionalization through metal-catalyzed coupling reactions. Tertiary ethers can be formed in good yield (e.g., 11, 65%) yielding the framework found in pharmaceutically relevant compounds such as HCV-371.[18]Geminally di-substituted pyran 12 can be obtained in high yields, which presents the opportunity for functional group manipulation of the di-ester.[30] When a secondary allylic ether is employed as a substrate, the corresponding 2,6-substituted pyran (13) is isolated in 71% yield with excellent diastereoselectivity (> 20:1 cis:trans).

The modulation of allylic ether attachment from C3 (type 1) on the indole core to C2 (type 2) accesses the isosteric tricylic pyrans (Table 2). The C-2 substituted allyl ether substrates were efficiently generated through a palladium catalyzed C–H activation utilizing primary alkyl halides.[31] With each of these substrates, the cyclization reaction provides the pyran products in moderate yields for the overall two-step tandem process. The 5-substituted indoles (e.g. 15–16) bearing electron withdrawing and electron donating groups are amenable to the reaction conditions but proceed in moderate yields. Allyl groups such as cinnamyl and 3,3-dimethyl allyl (e.g. 17–18) were also explored and found to be compatible, but required slightly higher iridium catalyst loading to fully isomerize the alkene. The core structure of spirocyclic indole-fused pyran 19 has been utilized as a antagonist for the 3-opiate receptor.[32]

The placement of the ether group on the nitrogen atom of the indole (type 3) provides increase substrate diversity compared type 1 & 2 cases due to the ease of synthesizing different allyl ether precursors from readily available aldehydes.[33]As with type 1 and 2, 5-substituted indoles were tolerant to the conditions generating pyrans 21 and 22 in excellent yield (77%, 90%, respectively). In addition to aromatic substituents, products such as 24 that have alkyl substitution at the C3 position can be obtained in high yields. Interestingly, in addition to six membered pyrans, cyclization to afford seven-membered oxepane 25 could also be achieved in this type 3 approach, which was not possible for type 1 and 2 analogs.

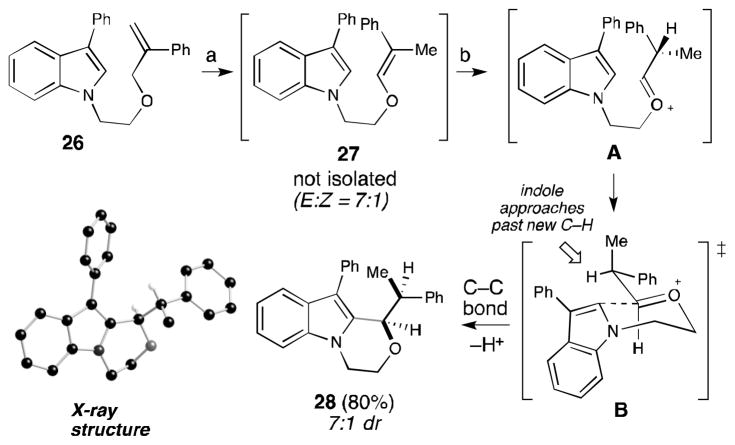

Internal substitution of the allyl ether substituent provides the opportunity to introduce stereochemical complexity to the overall isomerization/cyclization process. Hence, a 1,1-disubstituted-styrene ether substrate (26) was subjected to the Ir(III)/Bi(OTf)3 conditions (Scheme 1) generating 28 as a 7:1 mixture of diastereomers via intermediate oxocarbenium A. The major product is attributed to a chair-like transition state (B) with the indole approaching past the newly added C–H bond. A crystal structure of the major diastereomer proved the syn relative stereochemistry of 28. In contrast to simpler substrates, simultaneous addition of Ir(III)/Bi(OTf)3 did not fully facilitate the cyclization of substrate 26, which is presumably due to the known attenuated activity of the iridium catalyst towards internally substituted olefins.[9a] Consequently, a single flask, sequential approach was employed in which Bi(OTf)3 was added after isomerization to the enol ether with increased catalyst loadings of Ir(III).[34] Overall, this type 3 process offers the highest yields with the ability to easily access different pyrans and oxepane products and the opportunity to incorporate additional stereocenters with high levels of diastereoselectivity.

Scheme 1.

Diastereoselective example

a. 8 mol % [IrH2(THF)2(PPh2Me)2)]PF6 in THF (0.1M). b. 10 mol % Bi(OTf)3 added directly to flask.

Our current understanding of the cascade sequence is shown in Figure 3. The catalytic cycle begins with in situ generation of an active cationic iridium complex II by sparging hydrogen gas (via balloon) into a suspension of I in THF. After association with the substrate (5) to form complex III, a migratory insertion takes place and adds Ir–H across the olefin generating iridium complex IV. A β -hydride elimination of the iridium complex subsequently furnishes vinyl ether V that is equipped to be protonated. The triflic acid produced from Bi(OTf)3 effectively protonates the enol ether V, thereby generating the key oxocarbenium ion (VI) which then can undergo an oxa-Pictet Spengler reaction generating cyclized iminium ion VII. The aromatization of VII regenerates the Brønsted acid (TfOH) and ultimately furnishes pyran-fused indole 7.

Based on this reaction pathway, the tandem isomerization-cyclization provides a test platform for an enantioselective variant with chiral Brønsted acids. Chiral phosphoric acid (CPA) catalysis has emerged as a powerful strategy to promote various asymmetric transformations.[35] While the addition of nucleophiles to imines activated by CPAs is well developed, the generation of oxocarbenium ions and subsequent additions are far less advanced with only recent highly enantioselective ketalizations, and aldol-type reactions being described.[36] Outside of these examples however, there are few cases of oxocarbenium/chiral counterion catalysis utilizing CPAs limited instances of carbon nucleophile addition.[36a] Given the process described in Figure 3, a chiral phosphoric acid (H-CPA) could protonate the enol ether and the subsequent conjugate base CPA− would form a contact ion-pair to generate enantioenriched heterocyclic-fused indoles (Scheme 2). While the use of known chiral phosphoric acids instead of bismuth triflate in the one-pot isomerization/cyclization procedure from Table 2 afforded the pyran products with minimal levels of enantioselectivity (not shown), the purification of the intermediate enol ether (29) prior to addition of the phosphoric acid resulted in promising measurable levels of enantioselectivity. For example, in the presence of 10 mol % chiral phosphoric acid 30, N-substituted enol ether 29 provided oxazinoindole 20 with encouraging levels of enantioselectivity (Scheme 2). Through an extensive screening of various phosphoric acids (not shown) it was found that the 3,5-CF3-C6H3 substituted acid (30) at room temperature gave the highest enantioselectivity (80:20 er). Lowering the temperature did not improve enantioselectivity regardless of catalyst structure. This positive result marks the first example of an enantioselective method to generate oxazinoindoles and is only the second example of an enantioselective oxa-Pictet- Spengler reaction.[11]

Scheme 2.

Enantioselective oxa-Pictet Spengler

In summary, a mild and efficient process to generate a wide variety of heterocycle-fused indoles has been developed utilizing cooperative catalysis between an iridium(III) catalyst and bismuth triflate. Three distinct cyclization manifolds (type 1–3) lead to bioactive scaffolds that can be obtained in good yields through a one-pot reaction with low catalyst loadings while avoiding the traditional harsh conditions of Prins-type reactions. In addition, N-substituted indoles can be synthesized enantioselectively via an oxocarbenium•chiral phosphate counterion approach which provides a clear roadmap for further study of this asymmetric variant. The creation of focused pyran indole libraries through this method and subsequent biological evaluation are currently underway.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Catalytic Cycle

Footnotes

Financial support has been generously provided by the NIH P50 GM086145 and American Cancer Society (RSG-09-016-01-CDD). We thank Dr. Paul Siu (NU) for assistance with X-ray crystallography and Dr. Chris Check (NU) for mechanistic discussions.

Supporting information for this article is available on the Web under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

References

- 1.For reviews on THP synthesis and their prevalence in natural products, see: Boivin TLB. Tetrahedron. 1987;43:3309–3362.Clarke PA, Santos S. Eur J Org Chem. 2006:2045–2053.Smith AB, Fox RJ, Razler TM. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:675–687. doi: 10.1021/ar700234r.Olier C, Kaafarani M, Gastaldi S, Bertrand MP. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:413–445.

- 2.Ooi T, Maruoka K. In: Comprehensive Asymmetric Catalysis I–III. 3. Jacobsen EN, Pfaltz A, Yamamoto H, editors. Springer-Verlag; Berlin, Germany: 1999. pp. 1237–1254. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hilli F, White JM, Rizzacasa MA. Org Lett. 2004;6:1289–1292. doi: 10.1021/ol0497943.Fuwa H, Noto K, Sasaki M. Org Lett. 2011;13:1820–1823. doi: 10.1021/ol200333p.. For a recent review, see: Fuwa H. Heterocycles. 2012;85:1255–1298.

- 4.Fu GC, Grubbs RH. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:5426–5427.Wildemann H, Dunkelmann P, Muller M, Schmidt B. J Org Chem. 2003;68:799–804. doi: 10.1021/jo0264729.Crimmins MT, Jacobs DL. Org Lett. 2009;11:2695–2698. doi: 10.1021/ol900814w.. For a review, see: Deiters A, Martin SF. Chem Rev. 2004;104:2199–2238. doi: 10.1021/cr0200872.

- 5.a) Jaber JJ, Mitsui K, Rychnovsky SD. J Org Chem. 2001;66:4679–4686. doi: 10.1021/jo010232w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Keck GE, Covel JA, Schiff T, Yu T. Org Lett. 2002;4:1189–1192. doi: 10.1021/ol025645d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Morris WJ, Custar DW, Scheidt KA. Org Lett. 2005;7:1113–1116. doi: 10.1021/ol050093v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Clarke PA, Santos S, Mistry N, Burroughs L, Humphries AC. Org Lett. 2011;13:624–627. doi: 10.1021/ol102860r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Cui JY, Chai DI, Miller C, Hao JS, Thomas C, Wang JQ, Scheidt KA, Kozmin SA. J Org Chem. 2012;77:7435–7470. doi: 10.1021/jo301061r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Voigt T, Gerding-Reimers C, Tuyen TNT, Bergmann S, Lachance H, Scholermann B, Brockmeyer A, Janning P, Ziegler S, Waldmann H. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:410–414. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Aubele DL, Wan SY, Floreancig PE. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:3485–3488. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wender PA, DeChristopher BA, Schrier AJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6658–6659. doi: 10.1021/ja8015632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Custar DW, Zabawa TP, Hines J, Crews CM, Scheidt KA. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:12406–12414. doi: 10.1021/ja904604x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Crane EA, Scheidt KA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:8316–8326. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Yadav JS, Thrimurtulu N, Lakshmi KA, Prasad AR, Reddy BVS. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:661–663. [Google Scholar]; f) Crane EA, Zabawa TP, Farmer RL, Scheidt KA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:9112–9115. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Gesinski MR, Rychnovsky SD. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:9727–9729. doi: 10.1021/ja204228q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Wender PA, Schrier AJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:9228–9231. doi: 10.1021/ja203034k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lolkema LDM, Hiemstra H, Semeyn C, Speckamp WN. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:7115–7128.Roush WR, Dilley GJ. Synlett. 2001:955–959.Rychnovsky SD, Marumoto S, Jaber JJ. Org Lett. 2001;3:3815–3818. doi: 10.1021/ol0168465.Crosby SR, Harding JR, King CD, Parker GD, Willis CL. Org Lett. 2002;4:3407–3410. doi: 10.1021/ol020127o.Crosby SR, Harding JR, King CD, Parker GD, Willis CL. Org Lett. 2002;4:577–580. doi: 10.1021/ol0102850.Jasti R, Rychnovsky SD. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:13640–13648. doi: 10.1021/ja064783l. and references cited therein.

- 9.a) Yamamoto Y, Fujikawa R, Miyaura N. Synth Commun. 2000;30:2383–2391. [Google Scholar]; b) Sorimachi K, Terada M. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14452–14453. doi: 10.1021/ja807591m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ascic E, Hansen CL, Le Quement ST, Nielsen TE. Chem Commun. 2012;48:3345–3347. doi: 10.1039/c2cc17704h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson SG, Bungard CJ, Wang K. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:13000–13001. doi: 10.1021/ja037655v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Kopecky DJ, Rychnovsky SD. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:8420–8421. doi: 10.1021/ja011377n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chio FK, Warne J, Gough D, Penny M, Green S, Coles SJ, Hursthouse MB, Jones P, Hassall L, McGuire TM, Dobbs AP. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:5107–5124. [Google Scholar]

- 12.For a recent review, see: Larghi EL, Kaufman TS. Eur J Org Chem. 2011:5195–5231.

- 13.a) Larghi EL, Kaufman TS. Synthesis-Stuttgart. 2006:187–220. [Google Scholar]; b) Eid CN, Shim J, Bikker J, Lin M. J Org Chem. 2009;74:423–426. doi: 10.1021/jo801945n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Fernandes RA, Mulay SV. Synlett. 2010:2667–2671. [Google Scholar]; d) Sawant RT, Jadhav SG, Waghmode SB. Eur J Org Chem. 2010:4442–4449. [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Fernandes RA, Bruckner R. Synlett. 2005:1281–1285. [Google Scholar]; b) Saito A, Takayama M, Yamazaki A, Numaguchi J, Hanzawa Y. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:4039–4047. [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Lounasmaa M, Tolvanen A. Nat Prod Rep. 2000;17:175–191. doi: 10.1039/a809402k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Somei M, Yamada F. Nat Prod Rep. 2005;22:73–103. doi: 10.1039/b316241a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Cacchi S, Fabrizi G. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2873–2920. doi: 10.1021/cr040639b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Humphrey GR, Kuethe JT. Chem Rev. 2006;106:2875–2911. doi: 10.1021/cr0505270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Bandini M, Eichholzer A, Tragni M, Umani-Ronchi A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:3238–3241. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Akai S, Nemoto H, Egi M. Heterocycles. 2008;76:1537–1547. [Google Scholar]; b) Vyas S, Trivedi P, Chaturvedi SC. Acta Pol Pharm. 2009;66:201–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howe AYM, et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4813–4821. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.12.4813-4821.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coburn CA, Lavey BJ, Dwyer MP, Kozlowski JA, Rosenblum SB. WO2012050848-A1. 2012

- 19.Demerson CA, Santroch G, Humber LG, Charest MP. J Med Chem. 1975;18:577–580. doi: 10.1021/jm00240a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.a) An J, Chang NJ, Song LD, Jin YQ, Ma Y, Chen JR, Xiao WJ. Chem Commun. 2011;47:1869–1871. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03823g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gharpure SJ, Sathiyanarayanan AM. Chem Commun. 2011;47:3625–3627. doi: 10.1039/c0cc05558a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.For leading references regarding diversity oriented synthesis, see Schreiber SL. Science. 2000;287:1964–1969. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.1964.Burke MD, Berger EM, Schreiber SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:14095–14104. doi: 10.1021/ja0457415.; For recent examples, see: Kopp F, Stratton CF, Akella LB, Tan DS. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:358–365. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.911.Bauer RA, Wenderski TA, Tan DS. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:21–29. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1130.

- 22.a) Yamamoto Y, Miyairi T, Ohmura T, Miyaura N. J Org Chem. 1999;64:296–298. doi: 10.1021/jo9814288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yamamoto Y, Kurihara K, Yamada A, Takahashi M, Takahashi Y, Miyaura N. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:537–542. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dang TT, Boeck F, Hintermann L. J Org Chem. 2011;76:9353–9361. doi: 10.1021/jo201631x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reddy BVS, Sreelatha M, Kishore C, Borkar P, Yadav JS. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:2748–2751. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bouguerne B, Hoffmann P, Lherbet C. Synth Commun. 2010;40:915–926.Kwie FHA, Baudoin-Dehoux C, Blonski C, Lherbet C. Synth Commun. 2010;40:1082–1087.. The THF in these reactions was obtained from a GlassContours solvent purification system (alumina drying towers) with 5–10 ppm of H2O as measured by Karl Fischer titration.

- 26.a) Yadav JS, Reddy BVS, Chaya DN, Kumar G. Can J Chem. 2008;86:769–773. [Google Scholar]; b) Lherbet C, Soupaya D, Baudoin-Dehoux C, Andre C, Blonski C, Hoffmann P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:5449–5451. [Google Scholar]

- 27.For recent examples of cooperative catalysis/dual activation from our group, see Cardinal-David B, Raup DEA, Scheidt KA. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5345–5347. doi: 10.1021/ja910666n.Raup DEA, Cardinal-David B, Holte D, Scheidt KA. Nat Chem. 2010;2:766–771. doi: 10.1038/nchem.727.Cohen DT, Cardinal-David B, Scheidt KA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:1678–1682. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005908.Cohen DT, Cardinal-David B, Roberts JM, Sarjeant AA, Scheidt KA. Org Lett. 2011;13:1068–1071. doi: 10.1021/ol103112v.Dugal-Tessier J, O’Bryan EA, Schroeder TBH, Cohen DT, Scheidt KA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:4963–4967. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201643.Izquierdo J, Orue A, Scheidt KA. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:10634–10637. doi: 10.1021/ja405833m.

- 28.For a mini-review on cooperative catalysis with transition metals and Brønsted acids, see: Rueping M, Koenigs RM, Atodiresei I. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:9350–9365. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001140.. For recent examples, see: Wu H, He YP, Gong LZ. Adv Synth Catal. 2012;354:975–980.Fleischer S, Zhou SL, Werkmeister S, Junge K, Beller M. Chem Eur J. 2013;19:4997–5003. doi: 10.1002/chem.201204236.He YP, Wu H, Chen DF, Yu J, Gong LZ. Chem Eur J. 2013;19:5232–5237. doi: 10.1002/chem.201300052.

- 29.a) Li C, Villa-Marcos B, Xiao J. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:6967–6969. doi: 10.1021/ja9021683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rueping M, Koenigs RM. Chem Commun. 2011;47:304–306. doi: 10.1039/c0cc02167a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Tang W, Johnston S, Iggo JA, Berry NG, Phelan M, Lian L, Bacsa J, Xiao J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:1668–1672. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seayad J, Seayad AM, List B. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1086–1087. doi: 10.1021/ja057444l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiao L, Bach T. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:12990–12993. doi: 10.1021/ja2055066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hinez RSC, Schick H, Henkel B. US2005187281. 2005

- 33.Gore S, Baskaran S, Konig B. Org Lett. 2012;14:4568–4571. doi: 10.1021/ol302034r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.8 mol % of Ir(III) was added in 2 mol % portions over 1 hour intervals. The progress of the isomerization was monitored with 1HNMR spectroscopy.

- 35.For reviews on the transformations promoted with chiral phosphoric acids, see: Terada M. Synthesis. 2010:1929–1982.Kampen D, Reisinger CM, List B. Top Curr Chem. 2010;291:395–456. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-02815-1_1.

- 36.a) Terada M, Tanaka H, Sorimachi K. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3430–3431. doi: 10.1021/ja8090643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhang QW, Fan CA, Zhang HJ, Tu YQ, Zhao YM, Gu P, Chen ZM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:8572–8574. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Coric I, List B. Nature. 2012;483:315–319. doi: 10.1038/nature10932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Sun Z, Winschel GA, Borovika A, Nagorny P. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8074–8077. doi: 10.1021/ja302704m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Coric I, Kim JH, Vlaar T, Patil M, Thiel W, List B. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:3490–3493. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.