Abstract

We examined the hypothesis that family, peer and neighborhood violence would moderate relations between heavy alcohol use and adolescent dating violence perpetration such that relations would be stronger for teens in violent contexts. Random coefficients growth models were used to examine the main and interaction effects of heavy alcohol use and four measures of violence (family violence, friend dating violence, friend peer violence and neighborhood violence) on levels of physical dating violence perpetration across grades 8 through 12. The effects of heavy alcohol use on dating violence tended to diminish over time and were stronger in the spring than in the fall semesters. Consistent with hypotheses, across all grades, relations between heavy alcohol use and dating violence were stronger for teens exposed to higher levels of family violence and friend dating violence. However, neither friend peer violence nor neighborhood violence moderated relations between alcohol use and dating violence. Taken together, findings suggest that as adolescents grow older, individual and contextual moderators may play an increasingly important role in explaining individual differences in relations between alcohol use and dating violence. Implications for the design and evaluation of dating abuse prevention programs are discussed.

Keywords: Alcohol use, Dating violence, Adolescents, Developmental trajectory

Numerous studies have documented a consistent and robust link between alcohol use and adult intimate partner violence (for a review, see Foran and O’Leary 2008). The predominant theoretical explanation for this association, often called the proximal effects model (Klosterman and Fals-Stewart 2006), suggests that alcohol intoxication plays a causal role in increasing risk of partner aggression through its psychopharmacological effects on cognitive function. Specifically, alcohol intoxication can impair information-processing capacity, lead a person to overreact to perceived provocation and decrease the saliency of inhibitory cues, thereby increasing risk of violence (Phil and Hoaken 2002).

Although accumulating evidence from different lines of research provides strong support for the proximal effects model (Murphy et al. 2005), studies also indicate that, for many individuals, heavy drinking does not culminate in partner aggression (Schumacher et al. 2003), and that aggression may occur in the absence of alcohol use (Fals-Stewart 2003). Taken together, these findings suggest that other factors may moderate the relation between alcohol use and intimate partner violence. Indeed, several investigators have posited that the relation between the two behaviors likely varies considerably as a function of both individual (e.g., temperament) and contextual or situational (e.g., setting, relationship type) characteristics (Chermack and Giancola 1997; Foran and O’leary 2008; Klosterman and Fals-Stewart 2006; Leonard and Senchak 1993, 1996).

Despite a compelling empirical rationale for examining factors that may moderate relations between alcohol use and partner violence, few studies to date have done so (Fals-Stewart 2003; Fals-Stewart et al. 2005; Foran and O’Leary 2008; Schumacher et al. 2008). Moreover, to our knowledge, no studies have examined moderators of relations between alcohol use and dating violence during adolescence. Adolescence is an important developmental period for studying relations between alcohol use and partner violence given that both behaviors tend to initiate and then become increasingly prevalent during this period and both can have serious negative consequences for health and well-being (Ackard et al. 2007; Chassin et al. 2004). Furthermore, patterns of relationship conflict that are established during adolescence may carry over into young adulthood (Bouchey and Furman 2003). As such, a better understanding of how alcohol use and other risk factors act together to contribute to dating violence may inform primary prevention efforts that reduce levels of partner violence perpetration across the life-span.

Moderators of Relations Between Alcohol Use and Partner Violence

In their review of the role of drinking in partner violence, Klosterman and Fals-Stewart (2006) suggest that the most consistent moderator of relations between alcohol use and partner violence appears to be the presence of other factors that are causally related to aggression. This conclusion is consistent with theoretical models of relations between alcohol use and partner violence that explicitly account for the role of moderating factors including the selective disinhibition model (Parker 1995), the biopsychosocial model (Chermack and Giancola 1997), and the multiple threshold model (Fals-Stewart et al. 2005). While these models differ in scope and focus, they all espouse the basic hypothesis that alcohol will have a more pronounced effect on individuals who have aggressive propensities (e.g., for individuals with low aggressive inhibitions, trait anger or hostility, or an impaired capacity for behavioral regulation) and/or in contexts or situations that facilitate or encourage aggressive behavior (e.g., contexts where there are permissive norms regarding the use of aggression). In essence, the reasoning underlying this hypothesis suggests that: (i) everyone has a different threshold at which they are likely to engage in violence (holding level of provocation constant), (ii) alcohol intoxication increases risk of violence by weakening the cognitive controls that would otherwise constrain aggressive behavior (i.e., intoxication lowers the threshold at which aggression will occur), and (iii) accordingly, alcohol use will be even more likely to lead to aggression among individuals who have aggressive behavioral propensities (and/or in situations or contexts that facilitate aggressive behavior) because their aggression threshold will already be relatively low (but see Fals-Stewart et al. 2005, for a more nuanced discussion of how multiple thresholds may be set depending on violence severity and level of provocation).

One factor that may moderate the relation between alcohol use and dating violence is the level of violence in adolescents’ social environment. Social cognitive models (Bandura 1973) and empirical research suggest that adolescents who live and interact in social contexts (e.g., family, peer groups, and/or neighborhoods) where violence is prevalent may, through processes of modeling and reinforcement, internalize norms that are generally more accepting of violence, be less likely to expect negative sanctions to be imposed on their use of violence by institutions and others, and have diminished opportunities for learning constructive conflict resolution skills (Allwood and Bell 2008; Foshee et al. 1999; Kinsfogel and Grych 2004). Higher levels of contextual violence may thus contribute to the development of lower inhibitions against the use of aggression and a greater propensity to resort to aggressive response options when provoked (due to a lack of constructive conflict resolution skills). Accordingly, the relation between alcohol use and dating violence may be stronger for teens who are embedded in violent social contexts because these teens are more likely to have aggressive behavioral and perceptual propensities (i.e., their threshold for using aggression is relatively low).

The Current Study

The current study drew on the theoretical framework described above to examine whether and how contextual violence moderates relations between heavy alcohol use and physical dating violence perpetration during adolescence. Our central hypothesis was that relations between heavy alcohol use and dating violence perpetration would be stronger for adolescents who reported higher levels as compared to lower levels of contextual violence. To test our hypothesis, we examined the main and interaction effects of heavy alcohol use and four measures of contextual violence (family violence, friend dating violence, friend peer violence and neighborhood violence) on levels of dating violence perpetration across grades 8 through 12.

Measures were drawn from the family, peer, and neighborhood contexts because empirical studies have linked violence in each of these settings with dating aggression (Arriaga and Foshee 2004; Capaldi et al. 2001; Foshee et al. 1999; Kinsfogel and Grych 2004; Malik et al. 1997). In addition, because both theory and empirical evidence suggests that exposure to violence in one setting or context increases risk of exposure in another context (Mrug et al. 2008), the current study simultaneously evaluated all four measures of contextual violence within the same modeling framework, allowing us to examine the independent (or net) effects of violence within each context. Within the peer context, we examined both friend dating violence and friend peer violence as potential moderators because modeling and reinforcement of either of these behaviors may contribute to increase one’s propensity to aggress against a dating partner. While little research has examined sex differences in the relations that we consider in the current study, some studies suggest that the etiological processes leading to dating aggression may differ for boys and girls (e.g., Foshee et al. 2001). As such we examined the potential for sex differences in the main and interaction effects of heavy alcohol use and each contextual violence measure on dating violence perpetration by examining two- and three-way interactions. Similarly, we considered whether and how effects changed (i.e., increased or decreased) across the grade levels that were assessed.

Methods

The sample for this research was drawn from a multi-wave cohort sequential study of adolescent health risk behaviors that spanned middle and high school (Ennett et al. 2006). The current study uses four waves of data collected over a 2-year period starting when participants were in the fall semester of the 8th, 9th and 10th grades (wave one) and ending when participants were in the fall semester of the 10th, 11th, and 12th grades (wave four). Six-month time intervals separated the first three waves of data collection and a 1-year interval separated waves three and four. Participants were enrolled in two public school systems located in two predominantly rural counties with higher proportions of African Americans, higher high school dropout rates, and lower socioeconomic status than in the general United States (U.S. Census Bureau 2001).

At each assessment, all enrolled students in the targeted grades who were able to complete the survey in English and who were not in special education programs or out of school due to long-term suspension were eligible for the study. Parents had the opportunity to refuse consent for their child’s participation by returning a written form or by calling a toll-free telephone number. Adolescent assent was obtained from teens whose parents had consented immediately prior to the survey administration. Trained data collectors administered the questionnaires in student classrooms. To maintain confidentiality, teachers remained at their desks while students completed questionnaires and the students placed questionnaires in envelopes before returning them to the data collectors. No incentives were provided for student participation. The Institutional Review Board for the School of Public Health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill approved the data collection protocols.

At wave one, 6% of parents refused consent, 6% of adolescents declined to participate and 8% were absent on the days when data were collected for a total of 2636 (79% response rate) students completing a survey at wave one. For this study, analyses excluded students who; (1) reported being out of the typical age range of 12–19 for the grades studied (n=33, 1%), (2) did not report their dating status (n=83, 3%), (3) reported never dating across all of the assessments (n=171, 6%) or (4) were missing data on the dating violence measures across all waves of the study (n=38, 1%), yielding a sample size of 2311. Nearly all students participated in at least two waves of data collection (n=2157, 93%), with 75% participating in 3 or more waves (n=1741).

Approximately half of the sample was male (47%) and the self-reported race/ethnicity distribution was 45% White, 47% Black, and 8% other race/ethnicity. At wave 1, 40% of participants reported that the highest education obtained by either parent was high school or less. Baseline prevalence of any heavy alcohol use in the past 3 months was 19% and prevalence of any physical dating violence perpetration in the past 3 months was 18%.

Measures

Measures included physical dating violence perpetration, heavy alcohol use, four measures of contextual violence (family violence, friend peer violence, friend dating violence, and neighborhood violence) and three demographic controls (race, sex and parent education). Measures of heavy alcohol use and violence exposure were collected at each wave and were modeled as time-varying predictors. The values of the demographic controls were determined based on available data across all four waves of the survey and were modeled as time-invariant. All measures were based on adolescent self-report except for measures indexing friends use of peer and dating violence, which were constructed using sociometric methods described below.

Physical Dating Violence Perpetration was measured each wave using a short version of the Safe Dates Physical Perpetration Scale (Foshee et al. 1996). Adolescents were asked, “During the past 3 months, how many times did you do each of the following things to someone you were dating or on a date with? Don’t count it if you did it in self-defense or play.” Six behavioral items were listed: “pushed, grabbed, shoved, or kicked,” “slapped or scratched,” “physically twisted their arm,” “hit them with a fist or something else hard,” “beat them up,” and “assaulted them with a knife or gun.” Response categories ranged from zero (0) to ten times or more (5) in the past 3 months. Scores were summed to create a physical dating violence perpetration scale measure at each wave (average Cronbach’s α=.93).

Heavy alcohol use was assessed by four items asking adolescents how many times in the past 3 months they had: 3 or 4 drinks in a row, 5 or more drinks in a row, gotten drunk or very high from drinking alcohol, or been hung over. The items for this measure were adapted from two national studies: Monitoring the Future (Johnston et al. 2009) and the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Resnick et al. 1997). Response categories ranged from zero (0) to 10 or more times (5). Item scores were averaged to create a composite scale of heavy alcohol use at each wave (average Cronbach’s α=.95).

Family violence was assessed by three items from Bloom’s (1985) self-report measure of family functioning. Adolescents were asked how strongly they agreed or disagreed with the following items: we fight a lot in our family, family members sometimes get so angry they throw things and family members sometimes hit each other. Item scores were averaged to create a measure of family violence at each wave (average Cronbach’s α=.87).

Friend Perpetration of Peer and Dating Violence Measures of each respondent’s friends’ use of violence against dates and peers were constructed using sociometric methods. At each wave, adolescents were provided with a student directory that listed all enrolled students along with an identification number for each student. Participants used the identification number in the roster to identify up to five of their closest friends. Because the respondent’s friends in school were included in the data collection, their friends’ reports of violence rather than the respondent’s perceptions of their friends’ violence, were used to create measures that indexed friends’ dating violence perpetration (based on the measure of dating violence described above) and friends’ peer violence perpetration at each wave. Peer violence was assessed using the same six behavioral items used to assess dating violence, but respondents were prompted to report violent acts perpetrated against peers they were not dating. Scores were averaged across the items to create a composite scale of peer violence at each wave (average Cronbach’s α=.91).

To create each friend perpetration measure, we dichotomized the dating violence and peer violence measures for each friend and summed the number of friends who reported any perpetration of dating violence and the number who reported any perpetration of peer violence. To adjust for differential exposure to peer models due to variability in the number of friends nominated, a time-varying variable denoting the total number of friends in the adolescent’s friendship network at each wave was included as a control variable in all models.

Neighborhood Violence Teens responded to four items assessing their agreement or disagreement with statements about fear, violence and antisocial behavior in their neighborhood (people are afraid to come to my neighborhood, people there have violent arguments, people feel safe there, people sell illegal drugs in my neighborhood). Items were summed to create a composite scale of neighborhood violence (average Cronbach’s α=.94).

Demographic Covariates Sex was coded such that the reference group was female. Race/ethnicity was based on the adolescent’s modal response across all waves of assessment and dummy coded to include White (reference group), Black, and other race/ethnicity (including Latinos). Parent education, an indicator of family socioeconomic status (Goodman 1999), ranged from less than high school (0) to graduate school or more (5), and was measured as the highest level of education attained by either parent across all waves. Grade level was used as the metric of time and ranged from grade 8 (0) to grade 12 (4). Semester was coded as fall (0) and spring (1).

Analytic Strategy

The main purpose of this study was to determine if family, peer and neighborhood violence moderate the effect of heavy alcohol use on dating violence perpetration. To address this goal, we first used random coefficients growth curves to model trajectories of dating violence across grades 8 through 12. We then assessed the main and interaction effects of time-varying measures of heavy alcohol use and contextual violence on the repeated measures of dating violence. Data analysis occurred in several phases involving the reorganization of data based on grade rather than wave, imputation of missing data, centering of variables, estimation of unconditional dating violence trajectories and hypothesis testing.

First, to take advantage of the cohort sequential design of this study, data were reorganized such that the grade level of the adolescent was used as the primary metric of time rather than wave of assessment. This allowed for trajectories of dating violence to be continuously modeled across grades 8 through 12. After combining across cohorts and reorganizing the data by grade, information was available across eight discrete data points: grade 8 fall (n= 795), grade 8 spring (n=795), grade 9 fall (n=1586), grade 9 spring (n=791), grade 10 fall (n=2311), grade 10 spring (n=725), grade 11 fall (n=1516) and grade 12 fall (n=725). In preliminary analyses using this sample, we found no evidence of cohort differences in dating violence growth trajectories, suggesting that data from each of the cohorts could be combined to estimate a single developmental curve across grades 8 through 12. Dependence induced by nesting of students within schools was negligible (average intraclass correlation < .01, average design effect < 2.00), and adjusting for nesting had no effect on the growth factor means or variances. As such, the models reported below do not account for nesting of dating violence within schools, but are likely not biased by this omission.

We addressed the issue of missing data in our time-invariant and time-varying covariates through multiple imputation (Rubin 1987) using SAS PROC MI (SAS Institute 2003). Following standard recommendations, the imputation equation included all of the independent covariates (including Alcohol Use x Violence Exposure interactions), and dependent variables assessed at each of the grade levels (Allison 2001). Ten sets of missing values were imputed using multiple chain Marcov Chain Monte Carlo methods. Models were fit to each of the ten imputed datasets and parameter estimates and standard errors were combined using SAS PROC MIANALYZE (SAS Institute 2003). In order to appropriately disaggregate within- and between-person effects, time-varying measures were person-mean centered (heavy alcohol use and the violence exposure measures) and time-invariant demographic controls were grand-mean centered (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002, p. 183).

Several different models (e.g., flat, linear, quadratic) were estimated and compared to identify the functional form and error structure of the trajectory model that best fit the repeated measures of dating violence (for more detail on the process of determining the best-fitting trajectory model, see Reyes 2010). To adjust for non-normality in the distribution of the outcome, the repeated measures for dating violence were logged. The Bayesian Information Criterion, multivariate Wald tests, and component fit were used to determine the best-fitting model. The best-fitting model was quadratic in the fixed effects with time-varying (heteroscedastic) residual errors and a random intercept component. The slope and quadratic factor variances were negligible and non-significant and were therefore constrained to zero.

To test our hypotheses, we estimated a series of conditional multilevel models. We first estimated a baseline model that included the main effects of heavy alcohol use, each of the contextual violence measures and the demographic controls. Because previous research using this sample found significant interactions between alcohol use and grade level and between alcohol use and semester (spring vs. fall; Reyes et al. 2010), these interactions were also included in the baseline model. We next added various sets of interaction terms to the baseline model and determined the joint significance of their contribution to the model using multivariate Wald tests. The first set of interactions tested were those between heavy alcohol use and each of the contextual violence measures (four interaction terms). Next, to examine potential sex differences, we added two- and three-way interaction terms between sex, heavy alcohol use and each contextual violence measure (Sex x Alcohol Use, Sex x Contextual Violence, Sex x Alcohol Use x Contextual Violence). Finally, to examine whether the strength of the moderated effect varied across grade-levels and/or semesters, we added two- and three-way interactions between heavy alcohol use, each contextual violence measure and grade (Grade x Contextual Violence, Alcohol Use x Grade x Contextual Violence) and between heavy alcohol use, each contextual violence measure and semester (Semester x Contextual Violence, Alcohol Use x Semester x Contextual Violence). To produce a final reduced model, we dropped all sets of two- and three-way interactions that did not significantly contribute to the model according to the multivariate Wald test (α=.05). In addition, within each set of interactions that did contribute significantly to the model, we examined the individual t-tests of the parameter estimates for each interaction term and dropped all interactions that were not significant from the model.

Results

Replicating previous analyses using this sample (Reyes et al. 2010), findings from the unconditional growth model indicate that the average developmental trajectory for physical dating violence perpetration first increased over time (positive linear growth component, b=0.07, p=.002), peaked at the end of grade 10, and then desisted during late adolescence (negative quadratic growth component, b=–0.02, p=.01). There was significant variability in initial levels of dating violence perpetration (intercept variance, b=0.09, p<.001) and, estimates of residual variance in the repeated measures of perpetration were significant across all grade levels (p<.001 across all grades), indicating there was substantial variability in the repeated measures of perpetration that was not explained by the underlying trajectory process.

The results of the model assessing the main effects of heavy alcohol use and each of the violence exposure measures are presented in the first column of Table 1 (Baseline Model). Heavy alcohol use, family violence and friend dating violence were each significantly positively related to levels of dating violence perpetration, whereas neighborhood violence and friend peer violence were not. Consistent with previous research (Reyes et al. 2010), results also indicate that the strength of the main effect of heavy alcohol use on dating violence diminished across the grade levels assessed (Alcohol Use x Grade; b=–0.03, p<.01) and was stronger in the spring than in the fall semesters (Alcohol Use x Semester; b=0.14, p<.001).

Table 1.

Results for models examining measures of violence exposure as moderators of the effects of heavy alcohol use on dating violence across grades 8 through 12

| Independent variables | Baseline model b (SE) | Full model b (SE) | Reduced model b (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main effects | |||

| Semester | 0.03 (.02) | 0.02 (.02) | 0.02 (.02) |

| Grade | 0.03 (.03) | 0.03 (.03) | 0.03 (.03) |

| Grade*grade | −0.01 (.01) | −0.01 (.01) | −0.01 (.01) |

| Heavy alcohol use | 0.19 (.03)*** | 0.10 (.03)** | 0.11 (.03)** |

| Family violence | 0.04 (.01)*** | 0.03 (.01)*** | 0.03 (.01)** |

| Friend dating violence | 0.05 (.02)** | 0.02 (.02) | 0.02 (.02) |

| Friend peer violence | −0.01 (.01) | −0.01 (.01) | −0.01 (.01) |

| Neighborhood violence | 0.004 (.01) | 0.004 (.01) | 0.003 (.01) |

| Interactions | |||

| Heavy alcohol use*grade | −0.03 (.01)** | −0.03 (.01)* | −0.03 (.01)* |

| Heavy alcohol use*semester | 0.14 (.03)*** | 0.13 (.03)*** | 0.12 (.03)*** |

| Family violence* alcohol use | – | 0.03 (.01)*** | 0.03 (.01)*** |

| Friend dating violence* alcohol use | – | 0.09 (.02)*** | 0.09 (.02)*** |

| Friend peer violence* alcohol use | – | 0.01 (.01) | – |

| Neighborhood violence* alcohol use | – | −0.001 (.01) | – |

All models specified a random intercept quadratic trajectory for dating violence perpetration with heteroscedastic residual error over time and controlled for the effects of race, sex, parent education and number of friends. Independent predictor variables were all time-varying (level one).

p<.10;

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

The multivariate Wald test for the model that added all Alcohol Use x Contextual Violence interactions was significant (F(4, 110)=12.66, p<.001) and the parameter estimates from this model are presented in the second column of Table 1 (Full Model). Consistent with study hypotheses, there were significant positive interactions between alcohol use and family violence (p<.001) and between alcohol use and friend dating violence (p<.001) but, contrary to hypotheses, there were not significant interactions between heavy alcohol use and neighborhood violence or friend peer violence. Multivariate tests of all other sets of two- and three-way interactions (Sex x Alcohol Use, Sex x Contextual Violence, Sex x Alcohol Use x Contextual Violence; Grade x Contextual Violence, Alcohol Use x Grade x Contextual Violence; Semester x Contextual Violence, Alcohol Use x Semester x Contextual Violence) were not significant. These findings indicate that: (i) the main and interaction effects of heavy alcohol use and each of the contextual violence variables did not vary by sex, and (ii) the main effects of the contextual violence variables and the interactions between these variables and alcohol use did not vary significantly across grade levels or semesters.

The results of the final reduced model are presented in the third column of Table 1 (Reduced Model). Removing the non-significant interactions did not change the pattern of findings and had a minimal impact on parameter estimates. The positive interactions between heavy alcohol use and family violence (b=0.03, p<.001) and between heavy alcohol use and friend dating violence (b=0.09, p<.001) indicate that the association between alcohol use and levels of dating violence perpetration was stronger at higher as compared to lower levels of family violence and friend dating violence across all grade levels.

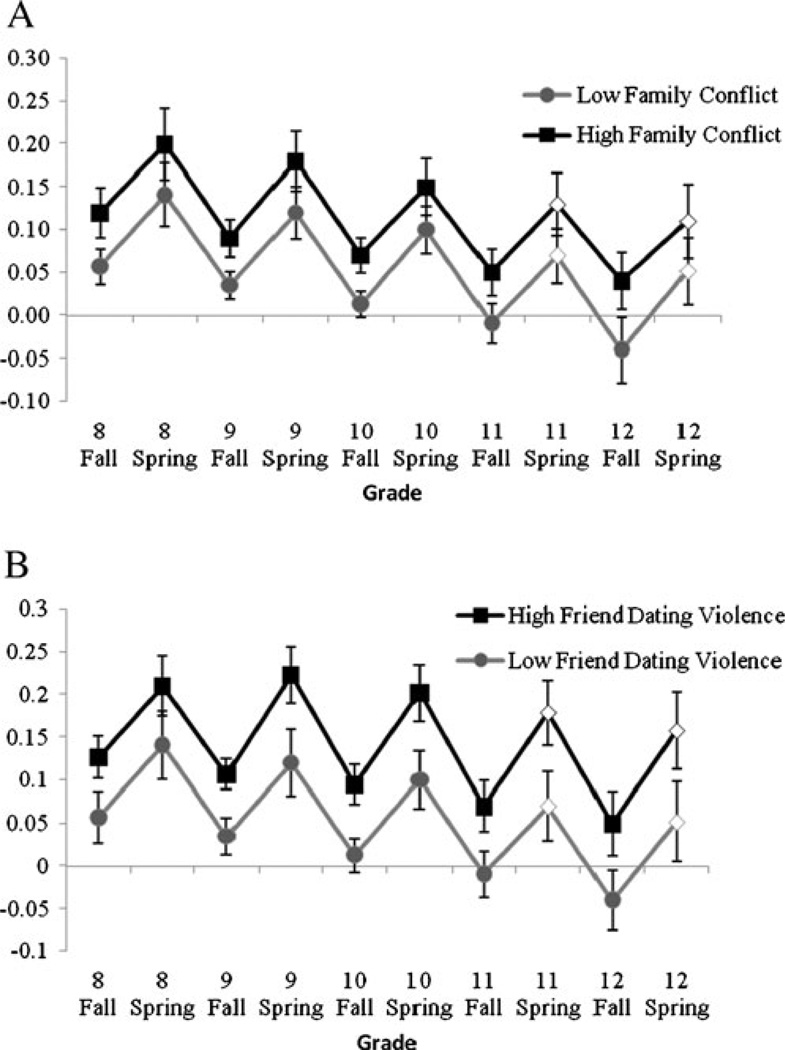

To further probe the pattern of moderated effects over time, we estimated the effect of heavy alcohol use at high (one standard deviation above the mean) and low (one standard deviation below the mean) levels of family violence and friend dating violence within each grade level assessed in the study. Results are presented in Fig. 1 (Panel A for family violence and Panel B for friend dating violence). Each panel depicts the effect of heavy alcohol use on dating violence perpetration (i.e., the regression coefficient associated with heavy alcohol use) at high and low levels of family and friend dating violence across grades 8 through 12. Although we did not assess individuals in grades 11.5 or 12.5 (the spring semesters of grade 11 and 12), we include the model-implied effects for these grade levels to show the predicted pattern from grade 8 fall semester through grade 12 spring semester.

Fig. 1.

Parameter estimates and standard errors for the effects of heavy alcohol use at low and high levels of family conflict (Panel A) and friend dating violence perpetration (Panel B) across grades 8 through 12. Family conflict and friend dating violence perpetration were set at −1 std below the mean (low) and +1 std above the mean (high). Effects at grades 11.5 and 12.5 were estimated based on model parameter estimates rather than observed

As shown in both figures, the difference between the effects of heavy alcohol use at high and low levels of family and friend dating violence was the same across all grade levels. That is, in each figure, the lines depicting the effects of heavy alcohol use at high and low levels of family and friend dating violence are parallel, reflecting the finding that the strength of each of the interaction effects (b =0.03 for family violence and b=0.09 for friend dating violence) did not change over time. The jagged pattern and the downward tilt of the lines in both figures reflect the findings that the strength of the effect of heavy alcohol use on dating violence at both high and low levels of family and friend dating violence was generally higher in the spring than in the fall semesters (Alcohol Use x Semester, b= 0.12), and tended to diminish across the grade levels assessed (Alcohol Use x Grade, b=–0.02). As a final step, we conducted significance tests of the parameter estimates for heavy alcohol use at high and low levels of family conflict and friend dating violence within each grade level. Results indicate that at high levels of family and friend dating violence, the effects of heavy alcohol use on dating violence perpetration were significant across nearly all grade levels (the fall semester of grade 12 is the only exception). In contrast, at low levels of family and friend dating violence, the effects of heavy alcohol use on dating violence were significant only in the spring semesters.

Discussion

Consistent with our hypotheses, we found that the strength of the association between heavy alcohol use and dating violence perpetration increased as levels of family violence and friend involvement in dating violence increased, and that this pattern of effects persisted across grades 8 through 12. In contrast, neighborhood violence and friend involvement in peer violence were not significantly associated with levels of dating violence perpetration and, contrary to expectations, neither of these variables moderated the effect of heavy alcohol use on dating violence. Furthermore, we found no evidence of sex differences in the direct or interaction effects of heavy alcohol use and each of the contextual violence measures on dating violence perpetration.

The finding that the effects of heavy alcohol use on dating violence perpetration are more pronounced for teens embedded in family and peer contexts where higher levels of relationship violence occur is consistent with the notion that such environments contribute to the development of aggressive behavioral and perceptual propensities that work synergistically with alcohol use to increase risk of dating aggression. Specifically, social cognitive theory suggests that teens who live and interact in violent family and peer contexts may, through processes of modeling and reinforcement, internalize norms that are more accepting of the use of dating aggression, develop more positive expectancies and fewer negative expectancies regarding the consequences of using dating violence (e.g., because they observe the mature social status or privilege conferred upon friends or family members who use violence and/or do not expect to be sanctioned by their peers for using dating violence), and have fewer opportunities to learn constructive conflict resolution strategies than teens whose family and friends are not involved in violence (Foshee et al. 1999). In turn, teens who have developed aggressive perceptual or behavioral tendencies as a result of their exposure to family violence and/or friend dating violence may be more susceptible to the disinhibiting effects of intoxication on dating violence perpetration because these teens already have a relatively low threshold at which they will engage in aggression.

Contrary to predictions, friend peer violence and neighborhood violence did not moderate relations between alcohol use and dating violence. One potential explanation for this finding is that only violence exposures that work specifically to influence cognitions concerning interactions within the context of intimate or romantic relationships contribute to moderate the effect of alcohol use on dating violence perpetration. That is, because higher levels of family violence and friend dating violence may lead to greater opportunities for observational learning and reinforcement of norms and behaviors that take place in the context of intimate or romantic relationships, family and friend dating violence may be more likely to moderate the effects of alcohol use on dating violence specifically than friend peer violence or neighborhood violence, which may influence cognitions related to aggression that targets peers or strangers, but not dates. This reasoning is consistent with Bandura’s (1973) observation, based on Social Learning theory, that disinhibition of aggression tends to be selective rather than indiscriminate (Bandura 1973, p.190).

Findings also indicate that whereas the main effect of heavy alcohol use on dating violence diminished over time, the strength of the moderating influences of family and friend dating violence on the relation between heavy alcohol use and dating violence did not vary by grade level. Taken together these findings suggest that, over time, moderating factors such as family and friend dating violence may play an increasingly important role in explaining individual differences in relationship between alcohol use and dating violence. That is, because the overall effect of heavy alcohol use on dating violence is stronger in early adolescence, heavy alcohol use tends to increase risk of dating violence perpetration for all young teens (though effects are stronger for those exposed to family and peer dating violence). In contrast, because the overall effect of heavy alcohol use tends to be weaker during late adolescence, heavy alcohol use may only increase risk of dating violence among older teens who have aggressive perceptual or behavioral propensities because they are embedded in violent family or peer contexts (this general time trend is depicted in Fig. 1).

We also briefly note that the main effects of heavy alcohol use on dating violence were stronger in the spring than in the fall semesters. The semester effect has been reported elsewhere and was not hypothesized a priori (Reyes et al. 2010). As such, this finding may be spurious and should be interpreted with caution before it is replicated by other studies. However, we note that this pattern of periodicity mirrors that of adolescent suicide and homicide event rates, which tend to peak during the spring semester (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2001). We speculate that one potential explanation for this pattern is that romantic relationships that develop in the fall and persist into the spring may be characterized by greater commitment and intimacy (including, for example, sexual intimacy) that may intensify alcohol-related conflict.

Finally, this study did not find evidence of sex differences in the main or interactive effects of heavy alcohol use and contextual violence on dating violence. In some ways these findings are consistent with previous research. For example, findings are consistent with research that has generally found alcohol use to be related to both male-to-female and female-to-male partner violence (Foran and O’Leary 2008). Similarly, exposure to violence has been associated with both male and female externalizing behaviors (e.g., Mrug et al. 2008). However, the literature on sex differences in the effects of violence exposure on aggression is very mixed, and researchers suggest sex differences may play out differently depending on the setting (e.g., family, community) and type of exposure (e.g., direct vs. indirect exposure; exposure to father-to-mother vs. mother-to-father violence) being considered (Allwood and Bell 2008; Malik 2008; Mrug et al. 2008; Olsen et al. 2010). Future research should therefore continue to examine the potential for sex differences in relations between heavy alcohol use, contextual violence and dating aggression using more detailed and comprehensive measures of contextual violence.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are several important limitations to this study. First, although our hypotheses suggest a direction of influence from alcohol use to dating violence, our study was not designed to distinguish amongst the various causal mechanisms that may explain covariation between alcohol use and dating violence. Specifically, because our models assessed contemporaneous relations between heavy alcohol use and dating violence at each grade level, we cannot infer causality or temporal ordering between the two behaviors, nor can we determine whether adolescents were drinking at the time of their involvement in dating violence. Second, the current study focused exclusively on one type of dating violence perpetration (physical) and on one type of substance use (heavy alcohol use). Future research should build on the current study by examining whether findings hold across different indicators of substance use (e.g., marijuana use, hard drug use) and/or different types of dating violence (e.g., psychological aggression, victimization experiences). Third, it is possible that neighborhood violence was not associated with dating aggression in this study because our sample was drawn from predominantly rural areas, limiting variability in participants’ exposure to “neighborhood” violence. More broadly, it is unclear whether the results of our study would generalize to suburban or urban populations

Finally, there are several measurement-related issues that are limitations of our study. Our measure of neighborhood violence only included one item that directly assessed exposure to violent behavior in the neighborhood. The other items assessed perceptions of neighborhood safety, fear, and exposure to the sale of illegal drugs in the neighborhood. While these types of items are often included in measures of neighborhood violence (Brandt et al. 2005), they do not directly assess violence and may not have adequately measured the theoretical construct of interest. Lastly, data were self-report and social desirability bias may have influenced survey responses.

Implications for Prevention

Findings from the current study have several implications for the design and evaluation of prevention programs. The significant main and interaction effects of heavy alcohol use and exposure to family violence on dating violence indicate that prevention programs that successfully reduce or prevent family violence and/or heavy alcohol use during adolescence may also prevent dating violence. These programs may include early childhood intervention efforts (family-based or school-based) that target the developmental antecedents of heavy alcohol use and/or promote family well-being, as well as alcohol use and family violence prevention programs for teens and their caregivers.

Results also suggest that dating violence prevention efforts should explicitly seek to reduce heavy alcohol use by teens on dates. Programs that target middle school-aged teens may be most effective in terms of achieving primary prevention, as findings indicate that involvement in dating violence perpetration tends to increase significantly across grades 8 through 10. Throughout adolescence, programs that successfully redress the negative cognitive and emotional effects of exposure to violence may increase inhibitions against the use of dating violence, thereby reducing alcohol-related dating violence perpetration. Findings further indicate that these prevention strategies may be equally effective in preventing alcohol-related dating violence perpetration by both boys and girls.

We consider the finding that friend involvement in dating violence had a strong and persistent exacerbating effect on the relation between heavy alcohol use and dating violence to be of particular importance. This finding suggests that abusive dating behaviors may be modeled and socially reinforced by close friends and suggests that prevention programs should directly address peer influences on dating behavior. For example, Kinsfogel and Grych (2004) posit that prevention strategies that are able to influence social norms (e.g., at the school or peer group level) may provide a form of social control that increases inhibitions against the use of dating aggression. In turn, stronger peer norms against dating abuse may weaken the disinhibiting effect of alcohol intoxication on dating violence.

Finally, while we highlight cognitive factors such as norms as possible mechanisms through which contextual violence may contribute to moderate relations between heavy alcohol use and dating violence, research also suggests that violence exposure may lead to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and emotional dysregulation (Allwood and Bell 2008; Kinsfogel and Grych 2004). In turn, emotional dysregulation may explain why heavy alcohol use has a stronger effect on dating violence for teens living in violent contexts. That is, because teens who are emotionally reactive are less able to control their behavior in response to provocation (and thus have a lower threshold for use of aggression), they may be more susceptible to the disinhibiting effects of intoxication on aggression. If this perspective is correct, it suggests that prevention efforts should target skills related to anger regulation among youth exposed to violence. Future studies should therefore examine both cognitive and emotional factors as potential explanations for why relations between heavy alcohol use and dating violence are stronger among teens who live and interact in violent family and peer contexts (i.e., through the testing of mediated moderation models). This information could inform prevention efforts targeted at reducing alcohol-related dating violence perpetration.

Contributor Information

Heathe Luz McNaughton Reyes, Department of Health Behavior and Health Education CB# 7440, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill NC 27599-7440 USA, mcnaught@email.unc.edu.

Vangie A. Foshee, Department of Health Behavior and Health Education CB# 7440, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill NC 27599-7440 USA

Daniel J. Bauer, L. L. Thurstone Psychometric Laboratory, Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3270, USA

Susan T. Ennett, Department of Health Behavior and Health Education CB# 7440, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill NC 27599-7440 USA

References

- Ackard DM, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Long-term impact of adolescent dating violence on the behavioral and psychological health of male and female youth. Journal of Pediatrics. 2007;151:476–481. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Allwood MA, Bell DJ. A preliminary examination of emotional and cognitive mediators in the relation between violence exposure and violent behaviors in youth. Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;36:989–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Arriaga XB, Foshee VA. Adolescent dating violence: Do adolescents follow in their friends’ or their parents’ footsteps? Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19:162–184. doi: 10.1177/0886260503260247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Aggression: A social learning analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom BL. A factor analysis of self-report measures of family functioning. Family Process. 1985;24:225–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1985.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchey HA, Furman W. Dating and romantic relationships in adolescence. In: Adams GR, Berzonsky M, editors. The Blackwell handbook of adolescence. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers; 2003. pp. 313–329. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt R, Ward CL, Dawes A, Flisher AJ. Epidemiological measurement of children’s and adolescent’s exposure to community violence: Working with the current state of the science. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2005;8:327–341. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-8811-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Dishion TJ, Stoolmiller M, Yoerger K. Aggression toward female partners by at-risk young men: The contribution of male adolescent friendships. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:61–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Temporal variations in school-associated student homicide and suicide events—United States, 1992–1999. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2001;50:657–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Hussong AM, Barrera M, Brooke SG, Molina RT, Ritter J. Adolescent substance use. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons; 2004. pp. 665–696. [Google Scholar]

- Chermack ST, Giancola PR. The relation between alcohol and aggression: An integrated biopsychosocial conceptualization. Clinical Psychology Review. 1997;17:621–649. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(97)00038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Hussong A, Faris R, Foshee VA, Cai L, et al. The peer context of adolescent substanceuse: Findings from social network analysis. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16:159–186. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W. The occurrence of partner physical aggression on days of alcohol consumption: A longitudinal diary study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:41–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Leonard KE, Birchler GR. The occurrence of male-to-female intimate partner violence on days of men’s drinking: The moderating effects of antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:239–248. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, O’Leary KD. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Linder GF, Bauman KE, Langwick SA, Arriaga XB, Heath JL, et al. The Safe Dates project: Theoretical basis, evaluation design, and selected baseline findings. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1996;12:39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Linder GF. Family violence and the perpetration of adolescent dating violence: Examining social learning and social control processes. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:331–342. [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Linder F, MacDougall J, Bangdiwala S. Gender differences in the longitudinal predictors of dating violence. Preventive Medicine. 2001;32:128–141. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman E. The role of socioeconomic status gradients in explaining differences in US adolescents’ health. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:1522–1528. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.10.1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Silverman JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use. 1975–2008. Volume 1: Secondary school students (NIH Publication No. 09-7402) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsfogel KM, Grych JH. Interparental conflict and adolescent dating relationships: Integrating cognitive, emotional and peer influences. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:505–515. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klosterman KC, Fals-Stewart W. Intimate partner violence and alcohol use: Exploring the role of drinking in partner violence and its implications for intervention. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2006;11:587–597. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Senchak M. Alcohol and premarital aggression among newlywed couples. Journal of Studies on Alcohol Supplement. 1993;11:96–108. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1993.s11.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Senchak M. Prospective prediction of husband marital aggression within newlywed couples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:369–380. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik NM. Exposure to domestic and community violence in a non risk sample: Associations with child functioning. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:490–504. doi: 10.1177/0886260507312945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik S, Sorenson SB, Aneshensel CS. Community and dating violence among adolescents: Perpetration and victimization. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1997;21:291–302. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S, Loosier PS, Windle M. Violence exposure across multiple contexts: Individual and joint effects on adjustment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78:70–84. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.78.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, Winters J, O’Farrell TJ, Fals-Stewart W, Murphy M. Alcohol consumption and intimate partner violence by alcoholic mean: Comparing violent and nonviolent conflicts. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:35–42. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JP, Parra GR, Bennett SA. Predicting violence in romantic relationships during adolescence and emerging adulthood: A critical review of the mechanisms by which familial and peer influences operate. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:411–422. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker RN, Rebhun LA. Alcohol and homicide: A deadly combination of two American traditions. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Phil RO, Hoaken PNS. Biological bases of addiction and aggression in close relationships. In: Wekerle C, Wall AM, editors. The violence and addition equation: Theoretical and clinical issues in substance abuse and relationship violence. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 2002. pp. 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278:823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes HLM. Developmental associations between adolescent alcohol use and dating violence perpetration. 2010 (Doctoral dissertation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2009). Dissertation Abstracts International, 71B (01). (Publication No. AAT 3387971) [Google Scholar]

- Reyes HLM, Foshee VA, Bauer DJ, Ennett SE. The role of heavy alcohol use in the developmental process of desistance in dating aggression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;39:239–250. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9456-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. Statistical analysis software (SAS), Version 9.1. Cary, NC: SAS; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Fals-Stewart W, Leonard KE. Domestic violence treatment referrals for men seeking alcohol treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;24:279–283. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Homish GG, Leonard KE, Quigley BM, Kearns-Bodkin JN. Longitudinal moderators of the relationship between excessive drinking and intimate partner violence in the early years of marriage. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:894–904. doi: 10.1037/a0013250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Profiles of general demographic characteristics 2000. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2001. [Google Scholar]