Abstract

Adult neurogenesis represents a striking example of structural plasticity in the mature brain. Research on adult mammalian neurogenesis today focuses almost exclusively on two areas: the subgranular zone (SGZ) in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, and the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricles. Numerous studies, however, have also reported adult neurogenesis in the hypothalamus, a brain structure that serves as a central homeostatic regulator of numerous physiological and behavioral functions, such as feeding, metabolism, body temperature, thirst, fatigue, aggression, sleep, circadian rhythms, and sexual behavior. Recent studies on hypothalamic neurogenesis have identified a progenitor population within a dedicated hypothalamic neurogenic zone. Furthermore, adult born hypothalamic neurons appear to play a role in the regulation of metabolism, weight, and energy balance. It remains to be seen what other functional roles adult hypothalamic neurogenesis may play. This review summarizes studies on the identification and characterization of neural stem/progenitor cells in the mammalian hypothalamus, in what contexts these stem/progenitor cells engage in neurogenesis, and potential functions of postnatally generated hypothalamic neurons.

Keywords: Hypothalamus, Neurogenesis, Neural progenitors, Stem cells, Adult, Function, Tanycytes, Development, Metabolism, Energy balance, Ventricular zone

1. Introduction

“Once development was ended, the fonts of growth and regeneration of the axons and dendrites dried up irrevocably. In the adult centers, the nerve paths are something fixed, and immutable: everything may die, nothing may be regenerated.

-Santiago Ramón y Cajal, 1928

For more than a century, medical science clung to a fundamental dogma: the adult brain is a static structure, and human beings are born with all the brain cells they will ever have. Over the last 15 years, however, studies have shown that neurogenesis, the generation of newborn neurons, occurs in the postnatal and adult human brain (Eriksson et al., 1998; Curtis et al., 2007; Quinones-Hinojosa and Chaichana, 2007). Understanding the functional consequences of this plasticity has been of great interest to the neuroscience field, and a variety of animal model studies have informed us that many of these newborn neurons survive and functionally integrate themselves into the working brain.

Anatomical evidence for ongoing neurogenesis in the adult mammalian central nervous system (CNS) was first described by Altman and Das (1965). However, the functional relevance of these findings was not clear at the time, and several decades passed before this finding aroused wide interest. It was not until the work of Nottebohm and colleagues in the mid-1980s, which demonstrated that newborn neurons in the adult songbird CNS were auditory-responsive, that the capacity of newborn neurons to functionally integrate into local neural circuitry was broadly accepted (Paton and Nottebohm, 1984; Alvarez-Buylla et al., 1988). Methodological advancements in electron microscopy techniques revealed that adult-generated mammalian hippocampal neurons could survive for an extended period and receive synaptic inputs (Kaplan and Hinds, 1977; Kaplan and Bell, 1984), further suggesting that neurogenesis could modify neural circuits. Advances in immunohistochemistry combined with 3H-thymidine-labeling demonstrated that adult neurogenesis was a robust phenomenon (Cameron et al., 1993). Immunohistochemical detection of neuronal markers and the introduction of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU), a synthetic thymidine analog lineage tracer of DNA replication (Kuhn et al., 1996), further propelled the understanding of adult neurogenesis in the mammalian CNS by allowing for broader visualization and stereological quantification of newborn neurons (Ming and Song, 2005).

Research on adult mammalian neurogenesis today focuses almost exclusively on two areas: the subgranular zone (SGZ) in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, where new dentate granule cells are generated, and the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricles, where new neurons are generated and migrate through the rostral migratory stream to the olfactory bulb (Ming and Song, 2005, 2011; Lie et al., 2004; Gould, 2007). However, neurogenesis has been reported in multiple brain regions outside the SGZ and SVZ (Gould, 2007), such as the basal forebrain (Palmer et al., 1995), striatum (Pencea et al., 2001; Reynolds and Weiss, 1992), amygdala (Rivers et al., 2008), substantia nigra (Lie et al., 2002), subcortical white matter (Nunes et al., 2003), and more recently the hypothalamus (Kokoeva et al., 2005; Migaud et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2012).

These findings, however, have been met with relatively subdued interest from the field, as the absolute levels of neurogenesis reported in vivo are substantially lower than that observed in the SVZ and SGZ. An important qualification to this assumption is that the ability to detect ongoing neurogenesis outside the highly vascularized SVZ and SGZ may be limited by the inadequacy of traditional methods used to reveal new-born neurons. Recent methods, such as intracerebroventricular (icv) delivery of BrdU, demonstrate that new cells are born continuously and in substantial numbers in the adult murine hypothalamus and that many of these cells appear to differentiate into neurons (Kokoeva et al., 2007). Additionally, very small numbers of neurons in classically neurogenic regions such as the hippocampus have been found to be critical to the regulation of memory formation (Han et al., 2009). Thus, even if levels of neurogenesis are low, this does not mean this process is not physiologically important.

While these studies on neurogenesis outside the SVZ and SGZ represent only a small fraction of the published studies on adult neurogenesis, the prospect of hypothalamic neurogenesis has aroused substantial interest due to this region’s role as a master regulator of neuroendocrine function. Furthermore, this region also serves as a central homeostatic regulator of numerous physiological and behavioral functions, such as feeding, metabolism, body temperature, thirst, fatigue, aggression, sleep, circadian rhythms, and sexual behaviors. It is also well established that various hypothalamic neuronal subtypes display high levels of morphological plasticity, suggesting that newly generated neurons may integrate quite readily into existing hypothalamic neural circuitry (Theodosis et al., 2004, 2006; Prevot et al., 2010).

Given the critical role that hypothalamic neural circuitry plays in maintaining physiological homeostasis, functional integration of newborn neurons and/or their release of hormones/peptides may result in disproportionately larger effects in physiology and behavior relative to other brain regions. This review summarizes studies on the identification and characterization of neural stem/progenitor cells in the mammalian hypothalamus, in what contexts these stem/progenitor cells engage in neurogenesis, and potential functions of postnatally generated hypothalamic neurons.

2. Postnatal and adult hypothalamic neurogenesis

Among the first studies describing observations of hypothalamic neurogenesis, were a series of experiments in which co-intraventricular infusion of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and the proliferative lineage tracer BrdU led to increased levels of BrdU labeling, not only in the SGZ and SVZ, but also in the hypothalamus, striatum, and other forebrain regions (Pencea et al., 2001). Within the hypothalamic parenchyma, these BrdU labeled cells were found in a widely scattered pattern with the density of labeled cells declining as a function of distance from the ventricular wall (Pencea et al., 2001). Notably, the fraction of BrdU+ cells co-labeled with βIII-tubulin, a neuron-specific marker, was substantially higher in the hypothalamus (~42%) than near the SVZ (~27%). Subsequent studies used BrdU incorporation to provide evidence for FGF and CNTF-induced neurogenesis in the adult hypothalamus (Xu et al., 2005; Kokoeva et al., 2005; Perez-Martin et al., 2010). While these studies suggested that adult neurogenesis, as measured by BrdU incorporation, can occur in the mammalian hypothalamus, the non-physiological levels of growth factors used in these experiments made it unclear to what degree adult neurogenesis occurs in basal conditions.

Studies into physiological levels of hypothalamic neurogenesis have been hampered by the lackluster observation of newborn neurons with a single peripheral pulse of BrdU, as generally carried out in studies of neurogenesis in the SVZ and SGZ. This may be due to a number of reasons including, but not limited to, permeability of blood–brain barrier, the existence of relatively slow dividing progenitors in the hypothalamus, and a more limited temporal neurogenic window in the hypothalamus versus other neurogenic niches in the brain. Firstly, parenchymal exposure to circulating levels of BrdU following a single peripheral pulse is most likely to be exceeding low compared to ventricular-associated brain regions. The observations of higher levels of BrdU incorporation near circumventricular organs (Bennett et al., 2009) and the SVZ/SGZ suggest these regions of be much more proliferative, or alternatively, more accessible to permeability by BrdU. Central administration or multiple peripheral BrdU injections, as opposed to a single peripheral dose administration are likely to be required in order for robust detection of hypothalamic neurogenesis (Kokoeva et al., 2007). Secondly, BrdU is incorporated during DNA synthesis. Single peripheral BrdU injections have a short half-life, and if hypothalamic neural progenitors have longer cell cycles compared to SVZ/SGZ derived progenitors, this may give the incorrect appearance of no/low levels of hypothalamic neurogenesis. Lastly, the temporal window in which hypothalamic neurogenesis occurs may be much more narrowly limited than in other neurogenic regions, which may be why hypothalamic neurogenesis is not a widely reported observation. The ability to develop robust tools to detect all types of proliferating (slow vs. fast dividing) neural progenitors will expand the realm of observation of adult neurogenesis in regions beyond the SVZ and SGZ. Indeed, hippocampal neurogenesis was ignored for decades because the technology to validate this phenomenon was not up to par until years after its initial observation. New tools for studying proliferating neural progenitors will open up many new studies into previously under-characterized candidate progenitor populations.

Subsequent studies, however, which deliver BrdU using a series of peripheral injections or intracerebral cannulation, suggested that neurogenesis does occur within the adult hypothalamus under baseline conditions (Lee et al., 2012; Kokoeva et al., 2007; Ahmed et al., 2008). The distribution of hypothalamic neurogenesis differs substantially between hypothalamic regions, with the hypothalamic median eminence (ME) showing 5-fold greater levels of relative neurogenesis than any other area (Lee et al., 2012). As with postnatal neurogenesis in the SGZ, the rate of ME neurogenesis decreases sharply with age (Lee et al., 2012). Interestingly, diet alters neurogenesis in different hypothalamic sub-regions. High-fat diet (HFD) substantially enhances adult neurogenesis in the hypothalamic ME (Lee et al., 2012), while inhibiting neurogenesis in the adjacent arcuate nucleus (McNay et al., 2012), suggesting that diet can play a role in altering energy balance circuits well into adulthood. This may be accomplished by selective generation of specific neuronal subtypes that promote or inhibit feeding (Lee et al., 2012), combined with elimination of neurons with opposing functions by selective apoptosis (McNay et al., 2011). The ability to sustain opposing regulatory mechanisms to maintain energy balance is essential for survival, and regulating these opposing processes of neurogenesis and apoptosis may serve as an important mechanism to alter the set points of homeostatic regulatory circuitry in the hypothalamus in response to physiological and environmental insults (Pierce and Xu, 2010).

3. Hypothalamic stem/progenitor cells

The identity and location of adult hypothalamic stem/progenitor cells still requires further clarification. The presence of a hypothalamic “germinal matrix” was first described by Altman and Das (1965) in the postnatal rat, in which an active proliferative state, similar to that observed in the SVZ and SGZ, existed in the ependymal layer of the third ventricle wall past one month of age. Micrographs of these observations were not published, however, and subsequent studies using 3H-thymidine to label dividing cells did not report significant levels of proliferation in the ependymal layer of the third ventricle (Alvarez-Buylla et al., 1990). Another study suggested adult born neurons could be derived from a hypothalamic subependymal layer cell population (Perez-Martin et al., 2010). Conversely, in many of the recent studies claiming to report adult hypothalamic neurogenesis, it appears that most BrdU+ cells are dispersed in the parenchyma rather than concentrated along the third ventricular wall (Migaud et al., 2010; Pencea et al., 2001; Kokoeva et al., 2005).

This distribution of BrdU+ cells is unlike any other previously reported pattern of embryonic or adult neurogenesis in vertebrates, where neurogenesis occurs in a clearly defined zone that usually borders the cerebral ventricles. This proliferating parenchymal cell population may represent additional progenitor populations. Future studies employing genetic fate mapping to prospectively lineage trace these hypothalamic parenchymal cells will reveal whether these cell populations may exist as a type of quiescence or slowly dividing neural progenitor population. Potential genetic tools to study this population may include using a hGFAPCreERT2 (Ganat et al., 2006), PDGFRα-CreERT2 (Rivers et al., 2008), GLAST-CreERT2 (de Melo et al., 2012), or alternative inducible Cre lines to label putative parenchymal progenitor cell candidates. This wide and fairly even distribution resembles that seen for oligodendrocyte precursor cells (Belachew et al., 2003), suggesting that newborn neurons in the hypothalamus could be derived from these cell types, although subsequent cell-fate lineage analysis revealed that this was not the case (Kang et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2012). Details describing the distribution of BrdU+ cells in the hypothalamus following various BrdU administration protocols are tabulated in a review by Migaud et al. (2010).

In addition to a hypothalamic parenchymal progenitor population, in vitro neurospheres derived from the hypothalamic juxta-ventricular zone (mixed ependymal, subependymal, and parenchymal cell populations), suggested that cells with neural stem/progenitor potential resided in the vicinity of the third ventricle (Markakis et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2005; Bennett et al., 2009). Unfortunately, the failure to use prospective in vivo cell fate-mapping approaches in these studies, such as retroviral labeling or Cre/lox based genetic labeling, makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions about the identity or location of any putative hypothalamic stem/progenitor cell population. The use of fate mapping techniques to supplement BrdU incorporation studies to firmly establish the existence of ongoing neurogenesis is particularly important given the fact that BrdU can in some circumstances be incorporated into postmitotic neurons (Yang et al., 2001; Kuan et al., 2004; Breunig et al., 2007).

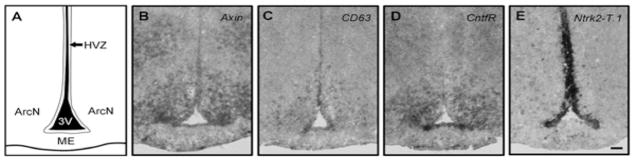

A recent large scale in situ hybridization screen revealed that the adult hypothalamic ventricular zone (HVZ) is enriched for neural stem and progenitor specific-genes (Fig. 1; Table 1; Lee et al., 2012; Shimogori et al., 2010), suggesting that the adult HVZ may serve as a reservoir of multipotent neural progenitors. In postnatal and adult rodent, this region is primarily composed of terminally differentiated multi-ciliated ependymal cells and specialized radial glia-like cells known as tanycytes (Horstmann, 1954), with the ventral HVZ composed exclusively of tanycytes (Mathew, 2008; Rodriguez et al., 2005).

Fig. 1.

The adult hypothalamic ventricular zone expresses stem and neural progenitor-specific markers. In situ hybridization of the adult murine hypothalamus reveals that the hypothalamic ventricular zone (HVZ) of the third ventricle (3V) expresses numerous neural stem and progenitor specific markers. (a) Coronal diagram of the mediobasal hypothalamus. Expression of the neural progenitor markers (b) Axin, (c) CD63, and (d) Ntrk2-T.1 are enriched in the hypothalamic ventricular zone. ME = median eminence. ArcN = arcuate nucleus. 8–12 week old female mice. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Table 1.

The adult hypothalamic ventricular zone expresses stem and neural progenitor-specific markers. A large-scale in situ hybridization screen of the hypothalamus reveals that the adult hypothalamic ventricular zone (HVZ) of the third ventricle (3V) expresses numerous neural stem and progenitor specific markers. Below are genes that enriched in tanycytes, tanycytes and a neuronal subset, tanycytes and glial subset, as well as tanycytes and ependymal cells. Data collated from in situ hybridization performed on coronal brain sections from 6 to 12 week old female mice.

| Tanycyte enriched | Tanycytes and neuronal subset | Tanycytes and glial subset | Tanycytes and ependymal cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rx, Nestin, Hes1, Hes5, Notch1, Notch 2, Fzd5, Dirc, CD63, Sox9, Ntrk2-T.1, Thrsp | Gpr50, Lhx2, Six3, Nfia, Cited1, Trps1, Nfix, Igfbp4, Gpr98 | GFAP, μ-crystallin, Ttyh1, Cspg2, Sox2 | Vimentin, Nnat, Ddr1, Mak |

Tanycytes are divided into four distinct subclasses, based on the position of their cell bodies along the ependymal wall, the projection of their basal processes, and their gene expression pattern (Rodriguez et al., 2005). α1 and α2 tanycytes are found along the ependymal surface of the ventromedial and arcuate nuclei, respectively. Their basal processes extend into the hypothalamic ependyma and form direct contacts with blood vessels and also, possibly, neurons. The β1 tanycytes, on the other hand, line the lateral portion of the infundibular recess, extend basal processes as far as the lateral edge of the ME, and form direct contacts with endothelial cells and close associations with the terminals of GnRH-expressing neurons. Finally, β2 tanycytes are found along the ventral surface of the infundibular recess and extend to the ventral surface of the ME, terminating on blood vessels of the portal circulation.

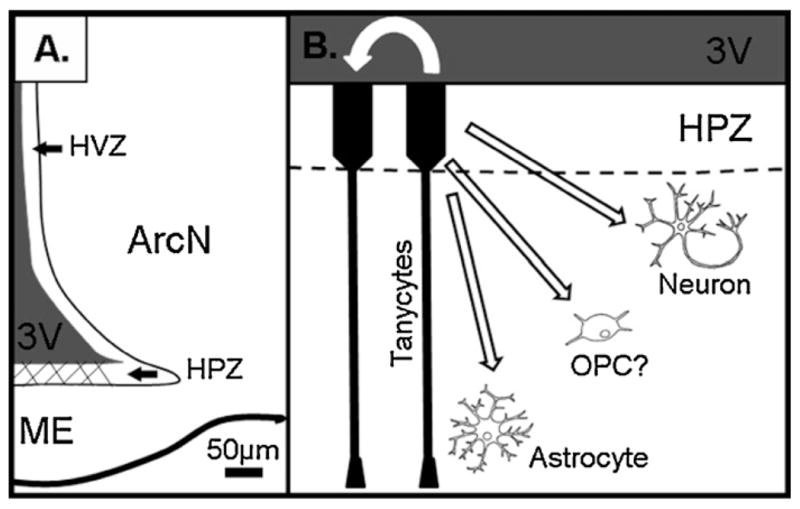

Tanycytes express a variety of markers characteristic of neural stem and progenitor cells (Table 1; Rodriguez et al., 2005), with β2 tanycytes expressing higher levels of some of these markers, such as Hes1 and Hes5 (Lee et al., 2012). β2 tanycytes have been directly shown to proliferate substantially at the floor of the third ventricle within the ME in a region termed the hypothalamic proliferative zone (HPZ) (Fig. 2; Lee et al., 2012). The rate of proliferation in the HPZ remains relatively high well into the fourth week of life, but declines substantially into adulthood (Lee et al., 2012). This is consistent with temporal changes in ME neurogenesis, which is substantially higher in the first few postnatal weeks than in adult animals (Lee et al., 2012). Lineage analysis using genetic fate mapping revealed that HPZ β2 tanycytes are the cell of origin of newborn neurons in the ME, and that β2 tanycytes are substantially more neurogenic than other tanycyte subtypes (Lee et al., 2012). Furthermore, these data demonstrate that tanycytes function as neural progenitors at significant levels in the ME, but not in other regions of the hypothalamus in vivo (Lee et al., 2012). In contrast, BrdU-labeled neurons found in the hypothalamic parenchyma, many at considerable distance from the ventricles (Migaud et al., 2010), may be generated from an as yet uncharacterized neural progenitor population.

Fig. 2.

Tanycytes of the hypothalamic median eminence are neural progenitors. (a) β2 tanycytes have been directly shown to proliferate substantially at the floor of the third ventricle within the ME in a region termed the hypothalamic proliferative zone (HPZ) (cross-hatching). The HPZ serves as a dedicated neurogenic niche within the ventral hypothalamic ventricular zone (HPZ). (b) HPZ tanycytes have been observed to generate astrocytes, neurons, and may generate oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs).

The ME, like other canonical neurogenic niches, is heavily vascularized. Endothelial cells play an essential role in regulating neural progenitor proliferation in the adult SVZ (Shen et al., 2008; Tavazoie et al., 2008), and raises the possibility that the unique vascular environment of the ME with fenestrated capillaries and fractones that often contact tanycytes (Mercier et al., 2003; Wittkowski, 1998), may play an active role in the neurogenic potential of β2 tanycytes. These structural similarities to the “neurogenic niche” environment found in the SVZ and SGZ suggest that the hypothalamic ME (HPZ) also serves as a neurogenic niche and warrants further attention towards obtaining a more detailed understanding of the contribution of HPZ-derived neurons to physiology and behavior.

While providing substantial insight into the identity of one population of hypothalamic neural progenitors, the study by Lee et al. (2012), raises several questions. What environmental conditions and/or molecular mechanisms regulate hypothalamic neurogenesis? Is ME neurogenesis limited to postnatal and young adult timepoints? Moreover, what is the turnover of the newborn neurons in the postnatal and adult ages? Do adult born ME neurons migrate? Finally, what is the cellular identity of other neural progenitor populations in the hypothalamus, and does a dedicated progenitor subtype exist in the hypothalamic parenchyma? Answering these questions will lead to a better understanding to the temporal window that these tanycytic neural progenitors can exert their plasticity onto existing hypothalamic circuitry.

4. Functional significance of adult hypothalamic neurogenesis

Another central unresolved question is the functional significance of postnatal hypothalamic neurogenesis. As expected from its relatively recent discovery, functional studies of neurogenesis in the adult hypothalamus are still in early exploratory stages. Given the role of the hypothalamus in feeding and metabolism, there has also been extensive interest in possible roles for hypothalamic neurogenesis in weight homeostasis. The first such studies involved the use of CNTF as a potential therapeutic treatment to induce weight loss (Kokoeva et al., 2005). Co-administration of CNTF and the anti-mitotic drug cytosine-b-d-arabinofuranoside (AraC) into the lateral ventricles blocked cell proliferation in the hypothalamus and reversed CNTF-induced weight loss. While these results suggest a possible role for hypothalamic neurogenesis in weight regulation, the fact that AraC blocks all cell proliferation throughout the brain leaves open the question of whether these effects are actually mediated by inhibition of hypothalamic neurogenesis.

Other studies have explicitly suggested a role for hypothalamic neurogenesis in energy regulation. New postnatal and adult born hypothalamic neurons express pSTAT3, a marker for functional activity, following leptin treatment (Lee et al., 2012; Kokoeva et al., 2005; Pierce and Xu, 2010). Furthermore, markers of terminally differentiated hypothalamic neuronal subtypes, such as agouti-related peptide (AGRP), pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) and neuropeptide Y (NPY) are expressed in these newly formed cells (Lee et al., 2012; Pierce and Xu, 2010; Kokoeva et al., 2005), suggesting that they may alter the metabolic homeostat through the release of neuropeptides, or by direct integration into local neural circuitry.

Upregulation of ME neurogenesis in response to HFD continues into adulthood (Lee et al., 2012), which raised the possibility that this process might also modulate hypothalamic neural circuitry late in life. Previous studies have implied that ongoing cell proliferation plays an important role in regulating feeding and metabolism (Pierce and Xu, 2010; Kokoeva et al., 2005). Whole brain X-irradiation leads to long-lasting changes in body weight (d’Avella et al., 1994), an effect which is not mimicked by focal irradiation of the hippocampus (Tan et al., 2011). In contrast, focal irradiation targeted to the HPZ, which selectively inhibits adult neurogenesis in the ME of HFD-fed animals, results in significant attenuation in weight gain and higher levels of activity and basal metabolism relative to controls (Lee et al., 2012). Furthermore, levels of observed adult neurogenesis (Hu+BrdU+DAPI+/Hu+DAPI+ neurons) in the arcuate nucleus were 0.75 ± 0.09% in sham treated mice versus 1.07 ± 0.11% in irradiated mice (mean ± standard error mean; p = 0.052; n = 3), thus suggesting that irradiation was not inhibiting neurogenesis within the adjacent arcuate nucleus, a hypothalamic substructure known to regulate feeding (Lee et al., 2012). This suggests that ME neurogenesis induced by overfeeding acts to reduce baseline energy consumption and promote energy storage in the form of fat. Such a response is likely adaptive in wild animals for which rich food sources are rare, but may prove maladaptive in laboratory housed mice (Blakemore and Froguel, 2008; Prentice et al., 2008). These findings raise the question of whether dietary triggers other than high-fat chow can regulate ME neurogenesis, and whether this effect is observed in humans.

An important caveat to the interpretation of these results (Lee et al., 2012) is the fact that since irradiation inhibits progenitor proliferation rather than neurogenesis per se, it is also possible that disrupted glia or other cell types in the ME may partially account for observed effects of irradiation. Furthermore, indirect effects, such as low-level inflammation, may play a role following irradiation. Blood tests measuring changes in blood cell components following irradiation in irradiated versus sham control groups, however, did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference between groups, thus suggesting that irradiated mice appeared to be relatively healthy compared to their sham counterparts (Lee et al., 2012; data not shown). Finally, looking forward into the near future, the development of tanycyte-specific genetic tools to inhibit the proliferation of tanycytic neural progenitors will provide substantial clarity as to the specific role tanycytes and their progeny play in the regulation of weight and metabolism.

The potential significance of the HPZ neural progenitor pool is magnified by its unique location in the ME, which lies outside the blood-brain barrier and receives convergent projections from a range of neurosecretory cells. Neurons whose cell bodies reside in the ME may regulate neuroendocrine function of the pituitary, by serving as receptors for circulating factors that do not readily enter the brain. Changes in the number and connectivity of ME neurons may thus have a functional impact disproportionately larger to their absolute quantity as has been shown in other regions of the brain (Han et al., 2007, 2009).

Tantalizingly, other studies aimed at studying hippocampal neurogenesis have also pointed to possible functions of adult hypothalamic neurogenesis. In a landmark study of the role of hippocampal neurogenesis in mediating response to antidepressants (Santarelli et al., 2003), the authors used X-irradiation on a vertically restricted region of mouse brain containing the hippocampus, and demonstrated both an inhibition of hippocampal neurogenesis and mitigation of behavioral effects following the administration of two classes of antidepressants. While the attenuated response to antidepressants observed in this study has generally been interpreted as resulting from inhibition of hippocampal neurogenesis, the irradiated column of tissue also includes the hypothalamus, and it is plausible that disruption of hypothalamic neurogenesis may in whole or in part account for the observed effects, particularly given the critical role of disruptions of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in the pathogenesis of depression. Many studies have tried to provide a link between the upregulation of hippocampal neurogenesis following anti-depressant treatment and behavioral effects, yet the undesirable side effects of anti-depressants (i.e. changes in weight, thirst, sleep, and sexual function) all involve disruption of homeostatic behaviors that are regulated by the hypothalamus. These antidepressant and behavioral studies suggest a possible role for hypothalamic neurogenesis in mood and behavior.

Environmental, social, hormonal, and behavioral signals may also regulate adult hypothalamic neurogenesis. Hippocampal neurogenesis can be altered by various hormones (Tanapat et al., 1998; Shingo et al., 2003), social behaviors (Fowler et al., 2002), enriched environments (Kempermann et al., 1998; van Praag et al., 1999), exercise (Kempermann et al., 1998; van Praag et al., 1999), and stress (Mirescu and Gould, 2006), all of which engage hypothalamic neural circuitry. Other studies have more directly demonstrated hormonal and behavioral-induced changes in hypothalamic neurogenesis. One study showed that BrdU+ neurons are generated during puberty in mice a sexually dimorphic manner in the anterior hypothalamus and preoptic area, as well as the amygdala, and that this difference was dependent on gonad hormones (Ahmed et al., 2008). Other work has also reported social isolation to modulate hypothalamic neurogenesis in prairie voles (Lieberwirth et al., 2012). The development of improved radiological tools (Lee et al., 2012; Ford et al., 2011), opotogenetics, and Cre/lox technology should facilitate the investigation of adult hypothalamic neurogenesis. Combined with targeted behavioral, metabolic, and physiological tests, these future studies will provide the temporal and spatial resolution to draw firm conclusions about the precise functional role of hypothalamic neurogenesis.

5. Conclusions

This mini-review summarizes recent research on hypothalamic neurogenesis into the following two topics: potential sources of hypothalamic neurogenesis, as well as the functional role that hypothalamic neurogenesis plays in the adult mammalian brain. Multiple studies have observed that neurospheres can be grown from adult hypothalamus and that BrdU incorporation is observed in hypothalamic neurons, consistent with the possibility that ongoing neurogenesis can occur in this brain region (Pencea et al., 2001; Markakis et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2005; Perez-Martin et al., 2010; Migaud et al., 2010; McNay et al., 2012). However, definitive evidence for ongoing postnatal hypothalamic neurogenesis requires the identification of the stem/progenitor cell population that give rise to newborn neurons, which until recently has been lacking. The identification of β2 tanycytes as neural progenitors capable of generating hypothalamic neurons in vivo, should both facilitate studies into the functional role of adult hypothalamic neurogenesis, as well as spur studies aimed at identifying other neural progenitor population in the hypothalamus (Lee et al., 2012). In addition, the observation that selective inhibition of ME neurogenesis alters weight and metabolism, illuminates the potential functional role that adult hypothalamic neurogenesis plays in the regulation of this physiological processes. Similar to previous studies involving the ablation of newborn neurons in other neurogenic niches (Arruda-Carvalho et al., 2011; Imayoshi et al., 2008), future studies involving the ablation of adult born hypothalamic neurons will hopefully reveal more insight into the role these newborn neurons play in physiology and homeostasis.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Bedont, E. Newman, and T. Pak for helpful comments on the manuscript and figures. This work was supported by a Basil O’Connor Starter Scholar Award and grants from the Klingenstein Fund and NARSAD (to S.B.). S.B. is a W.M. Keck Distinguished Young Scholar in Medical Research.

Abbreviations

- Ara-C

cytosine-b-d-arabinofuranoside

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- BrdU

bromodeoxyuridine

- CNTF

ciliary neurotrophic factor

- CNS

central nervous system

- HFD

high-fat diet

- HPZ

hypothalamic proliferative zone

- HVZ

hypothalamic ventricular zone

- ME

median eminence

- SGZ

subgranular zone

- SVZ

subventricular zone

References

- Ahmed EI, Zehr JL, Schulz KM, Lorenz BH, DonCarlos LL, Sisk CL. Pubertal hormones modulate the addition of new cells to sexually dimorphic brain regions. Nature Neuroscience. 2008;11 (9):995–997. doi: 10.1038/nn.2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Das GD. Autoradiographic and histological evidence of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1965;124 (3):319–335. doi: 10.1002/cne.901240303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Buylla A, Theelen M, Nottebohm F. Birth of projection neurons in the higher vocal center of the canary forebrain before, during, and after song learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:8722–8726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.22.8722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Buylla A, Theelen M, Nottebohm F. Proliferation hot spots in adult avian ventricular zone reveal radial cell division. Neuron. 1990;5 (1):101–109. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90038-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arruda-Carvalho M, Sakaguchi M, Akers KG, Josselyn SA, Frankland PW. Posttraining ablation of adult-generated neurons degrades previously acquired memories. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2011;31 (42):15113–15127. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3432-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belachew S, Chittajallu R, Aguirre AA, Yuan X, Kirby M, Anderson S, et al. Postnatal NG2 proteoglycan-expressing progenitor cells are intrinsically multipotent and generate functional neurons. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2003;161 (1):169–186. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett L, Yang M, Enikolopov G, Iacovitti L. Circumventricular organs: a novel site of neural stem cells in the adult brain. Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences. 2009;41 (3):337–347. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore AI, Froguel P. Is obesity our genetic legacy? The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;93 (11 Suppl 1):S51–S56. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breunig JJ, Arellano JI, Macklis JD, Rakic P. Everything that glitters isn’t gold: a critical review of postnatal neural precursor analyses. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1 (6):612–627. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron HA, Woolley CS, McEwen BS, Gould E. Differentiation of newly born neurons and glia in the dentate gyrus of the adult rat. Neuroscience. 1993;56 (2):337–344. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90335-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MA, Kam M, Nannmark U, Anderson MF, Axell MZ, Wikkelso C, et al. Human neuroblasts migrate to the olfactory bulb via a lateral ventricular extension. Science (New York, NY) 2007;315 (5816):1243–1249. doi: 10.1126/science.1136281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Avella D, Cicciarello R, Gagliardi ME, Albiero F, Mesiti M, Russi E, et al. Progressive perturbations in cerebral energy metabolism after experimental whole-brain radiation in the therapeutic range. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1994;81 (5):774–779. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.81.5.0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Melo J, Miki K, Rattner A, Smallwood P, Zibetti C, Hirokawa K, et al. Injury-independent induction of reactive gliosis in retina by loss of function of the LIM homeodomain transcription factor Lhx2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109 (12):4657–4662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107488109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Bjork-Eriksson T, Alborn AM, Nordborg C, Peterson DA, et al. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nature Medicine. 1998;4 (11):1313–1317. doi: 10.1038/3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford EC, Achanta P, Purger D, Armour M, Reyes J, Fong J, et al. Localized CT-guided irradiation inhibits neurogenesis in specific regions of the adult mouse brain. Radiation Research. 2011;175 (6):774–783. doi: 10.1667/RR2214.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler CD, Liu Y, Ouimet C, Wang Z. The effects of social environment on adult neurogenesis in the female prairie vole. Journal of Neurobiology. 2002;51 (2):115–128. doi: 10.1002/neu.10042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganat YM, Silbereis J, Cave C, Ngu H, Anderson GM, Ohkubo Y, et al. Early postnatal astroglial cells produce multilineage precursors and neural stem cells in vivo. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2006;26 (33):8609–8621. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2532-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E. How widespread is adult neurogenesis in mammals? Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 2007;8 (6):481–488. doi: 10.1038/nrn2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JH, Kushner SA, Yiu AP, Cole CJ, Matynia A, Brown RA, et al. Neuronal competition and selection during memory formation. Science (New York, NY) 2007;316 (5823):457–460. doi: 10.1126/science.1139438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JH, Kushner SA, Yiu AP, Hsiang HL, Buch T, Waisman A, et al. Selective erasure of a fear memory. Science (New York, NY) 2009;323 (5920):1492–1496. doi: 10.1126/science.1164139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horstmann E. Die Faserglia des Selachiergehirns (The fiber glia of selacean brain) Zeitschrift fur Zellforschung und mikroskopische Anatomie (Vienna, Austria: 1948) 1954;39 (6):588–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imayoshi I, Sakamoto M, Ohtsuka T, Takao K, Miyakawa T, Yamaguchi M, et al. Roles of continuous neurogenesis in the structural and functional integrity of the adult forebrain. Nature Neuroscience. 2008;11 (10):1153–1161. doi: 10.1038/nn.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SH, Fukaya M, Yang JK, Rothstein JD, Bergles DE. NG2+ CNS glial progenitors remain committed to the oligodendrocyte lineage in postnatal life and following neurodegeneration. Neuron. 2010;68 (4):668–681. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan MS, Bell DH. Mitotic neuroblasts in the 9-day-old and 11-monthold rodent hippocampus. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1984;4 (6):1429–1441. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-06-01429.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan MS, Hinds JW. Neurogenesis in the adult rat: electron microscopic analysis of light radioautographs. Science (New York, NY) 1977;197 (4308):1092–1094. doi: 10.1126/science.887941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempermann G, Kuhn HG, Gage FH. Experience-induced neurogenesis in the senescent dentate gyrus. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1998;18 (9):3206–3212. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03206.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokoeva MV, Yin H, Flier JS. Neurogenesis in the hypothalamus of adult mice: potential role in energy balance. Science (New York, NY) 2005;310 (5748):679–683. doi: 10.1126/science.1115360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokoeva MV, Yin H, Flier JS. Evidence for constitutive neural cell proliferation in the adult murine hypothalamus. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2007;505 (2):209–220. doi: 10.1002/cne.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuan CY, Schloemer AJ, Lu A, Burns KA, Weng WL, Williams MT, et al. Hypoxia-ischemia induces DNA synthesis without cell proliferation in dying neurons in adult rodent brain. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2004;24 (47):10763–10772. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3883-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn HG, Dickinson-Anson H, Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the adult rat: age-related decrease of neuronal progenitor proliferation. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1996;16 (6):2027–2033. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-06-02027.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DA, Bedont JL, Pak T, Wang H, Song J, Miranda-Angulo A, et al. Tanycytes of the hypothalamic median eminence form a diet-responsive neurogenic niche. Nature Neuroscience. 2012;15 (5):700–702. doi: 10.1038/nn.3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lie DC, Dziewczapolski G, Willhoite AR, Kaspar BK, Shults CW, Gage FH. The adult substantia nigra contains progenitor cells with neurogenic potential. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2002;22 (15):6639–6649. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06639.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lie DC, Song H, Colamarino SA, Ming GL, Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the adult brain: new strategies for central nervous system diseases. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2004;44:399–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberwirth C, Liu Y, Jia X, Wang Z. Social isolation impairs adult neurogenesis in the limbic system and alters behaviors in female prairie voles. Hormones and Behavior. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.03.005. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markakis EA, Palmer TD, Randolph-Moore L, Rakic P, Gage FH. Novel neuronal phenotypes from neural progenitor cells. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2004;24 (12):2886–2897. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4161-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew TC. Regional analysis of the ependyma of the third ventricle of rat by light and electron microscopy. Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia. 2008;37 (1):9–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0264.2007.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNay DE, Briancon N, Kokoeva MV, Maratos-Flier E, Flier JS. Remodeling of the arcuate nucleus energy-balance circuit is inhibited in obese mice. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2012;122 (1):142–152. doi: 10.1172/JCI43134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercier F, Kitasako JT, Hatton GI. Fractones and other basal laminae in the hypothalamus. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2003;455 (3):324–340. doi: 10.1002/cne.10496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migaud M, Batailler M, Segura S, Duittoz A, Franceschini I, Pillon D. Emerging new sites for adult neurogenesis in the mammalian brain: a comparative study between the hypothalamus and the classical neurogenic zones. The European Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;32 (12):2042–2052. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming GL, Song H. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian central nervous system. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2005;28:223–250. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.051804.101459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming GL, Song H. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian brain: significant answers and significant questions. Neuron. 2011;70 (4):687–702. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirescu C, Gould E. Stress and adult neurogenesis. Hippocampus. 2006;16 (3):233–238. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes MC, Roy NS, Keyoung HM, Goodman RR, McKhann G, 2nd, Jiang L, et al. Identification and isolation of multipotential neural progenitor cells from the subcortical white matter of the adult human brain. Nature Medicine. 2003;9 (4):439–447. doi: 10.1038/nm837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer TD, Ray J, Gage FH. FGF-2-responsive neuronal progenitors reside in proliferative and quiescent regions of the adult rodent brain. Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences. 1995;6 (5):474–486. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1995.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton JA, Nottebohm FN. Neurons generated in the adult brain are recruited into functional circuits. Science (New York, NY) 1984;225 (4666):1046–1048. doi: 10.1126/science.6474166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pencea V, Bingaman KD, Wiegand SJ, Luskin MB. Infusion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor into the lateral ventricle of the adult rat leads to new neurons in the parenchyma of the striatum, septum, thalamus, and hypothalamus. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2001;21 (17):6706–6717. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06706.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Martin M, Cifuentes M, Grondona JM, Lopez-Avalos MD, Gomez-Pinedo U, Garcia-Verdugo JM, et al. IGF-I stimulates neurogenesis in the hypothalamus of adult rats. The European Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;31 (9):1533–1548. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce AA, Xu AW. De novo neurogenesis in adult hypothalamus as a compensatory mechanism to regulate energy balance. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30 (2):723–730. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2479-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice AM, Hennig BJ, Fulford AJ. Evolutionary origins of the obesity epidemic: natural selection of thrifty genes or genetic drift following predation release? International Journal of Obesity. 2008;32 (11):1607–1610. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevot V, Bellefontaine N, Baroncini M, Sharif A, Hanchate NK, Parkash J, et al. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone nerve terminals, tanycytes and neurohaemal junction remodelling in the adult median eminence: functional consequences for reproduction and dynamic role of vascular endothelial cells. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2010;22 (7):639–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.02033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinones-Hinojosa A, Chaichana K. The human subventricular zone: a source of new cells and a potential source of brain tumors. Experimental Neurology. 2007;205 (2):313–324. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds BA, Weiss S. Generation of neurons and astrocytes from isolated cells of the adult mammalian central nervous system. Science (New York, NY) 1992;255 (5052):1707–1710. doi: 10.1126/science.1553558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivers LE, Young KM, Rizzi M, Jamen F, Psachoulia K, Wade A, et al. PDGFRA/NG2 glia generate myelinating oligodendrocytes and piriform projection neurons in adult mice. Nature Neuroscience. 2008;11 (12):1392–1401. doi: 10.1038/nn.2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez EM, Blazquez JL, Pastor FE, Pelaez B, Pena P, Peruzzo B, et al. Hypothalamic tanycytes: a key component of brain–endocrine interaction. International Review of Cytology. 2005;247:89–164. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(05)47003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarelli L, Saxe M, Gross C, Surget A, Battaglia F, Dulawa S, et al. Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science (New York, NY) 2003;301 (5634):805–809. doi: 10.1126/science.1083328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Q, Wang Y, Kokovay E, Lin G, Chuang SM, Goderie SK, et al. Adult SVZ stem cells lie in a vascular niche: a quantitative analysis of niche cell-cell interactions. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3 (3):289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimogori T, Lee DA, Miranda-Angulo A, Yang Y, Wang H, Jiang L, et al. A genomic atlas of mouse hypothalamic development. Nature Neuroscience. 2010;13 (6):767–775. doi: 10.1038/nn.2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shingo T, Gregg C, Enwere E, Fujikawa H, Hassam R, Geary C, et al. Pregnancy-stimulated neurogenesis in the adult female forebrain mediated by prolactin. Science (New York, NY) 2003;299 (5603):117–120. doi: 10.1126/science.1076647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan YF, Rosenzweig S, Jaffray D, Wojtowicz JM. Depletion of new neurons by image guided irradiation. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2011;5:59. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2011.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanapat P, Galea LA, Gould E. Stress inhibits the proliferation of granule cell precursors in the developing dentate gyrus. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the International Society for Developmental Neuroscience. 1998;16 (3–4):235–239. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(98)00029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavazoie M, Van der Veken L, Silva-Vargas V, Louissaint M, Colonna L, Zaidi B, et al. A specialized vascular niche for adult neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3 (3):279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodosis DT, Koksma JJ, Trailin A, Langle SL, Piet R, Lodder JC, et al. Oxytocin and estrogen promote rapid formation of functional GABA synapses in the adult supraoptic nucleus. Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences. 2006;31 (4):785–794. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodosis DT, Schachner M, Neumann ID. Oxytocin neuron activation in NCAM-deficient mice: anatomical and functional consequences. The European Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;20 (12):3270–3280. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Praag H, Christie BR, Sejnowski TJ, Gage FH. Running enhances neurogenesis, learning, and long-term potentiation in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96 (23):13427–13431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittkowski W. Tanycytes and pituicytes: morphological and functional aspects of neuroglial interaction. Microscopy Research and Technique. 1998;41 (1):29–42. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19980401)41:1<29::AID-JEMT4>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Tamamaki N, Noda T, Kimura K, Itokazu Y, Matsumoto N, et al. Neurogenesis in the ependymal layer of the adult rat 3rd ventricle. Experimental Neurology. 2005;192 (2):251–264. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Geldmacher DS, Herrup K. DNA replication precedes neuronal cell death in Alzheimer’s disease. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2001;21 (8):2661–2668. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02661.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]