Abstract

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) promotes cancer invasion and metastasis, but the integrative mechanisms that coordinate these processes are incompletely understood. In this study, we used a cross-species expression profiling strategy in metastatic cell lines of human and mouse origin to identify 22 up-regulated and 12 down-regulated genes that are part of an essential genetic program in metastasis. In particular, we identified a novel function in metastasis that was not previously known for the transcription factor Forkhead Box Q1 (Foxq1). Ectopic expression of Foxq1 increased cell migration and invasion in vitro, enhanced the lung metastatic capabilities of mammary epithelial cells in vivo, and triggered a marked EMT. In contrast, Foxq1 knockdown elicited converse effects on these phenotypes in vitro and in vivo. Neither ectopic expression nor knockdown of Foxq1 significantly affected cell proliferation or colony formation in vitro. Notably, Foxq1 repressed expression of the core EMT regulator E-cadherin by binding to the E-box in its promoter region. Further mechanistic investigation revealed that Foxq1 expression is regulated by TGF-β1, and that Foxq1 knockdown blocked TGF-β1-induced EMT at both morphological and molecular levels. Our findings highlight the feasibility of cross-species expression profiling as a strategy to identify metastasis-related genes, and they reveal that EMT induction is a likely mechanism underlying a novel metastasis-promoting function of Foxq1 defined here in breast cancer.

Introduction

Metastasis, by which tumor cells disseminate from the site of the primary tumor and establish secondary tumors in distant organs, is one of the 6 distinct hallmarks of cancer (1). Clinically defined, metastasis is the major cause of lethality among human cancer patients, including those with breast cancer (2, 3). Targeted therapy for metastatic disease is clinically unavailable because the molecular mechanism underlying metastasis remains unclear (4). Therefore, identifying functional metastasis genes and their molecular mechanisms underlying the metastatic process remains a top priority in the cancer research field.

With the help of DNA microarray technology, several groups of gene signatures were identified in retrospective studies. These gene signatures can be used as the strongest predictors for overall survival and metastasis-free survival. They may also be used to predict outcomes in patients of all age groups with lymph-node-negative breast cancer (5–7). By means of in vivo selection and the cDNA microarray, 2 sets of genes were identified that mark and mediate breast cancer metastasis in specific organs, including the lungs and bones (8–10). Using a similar strategy, a group of important transcription factors playing a significant role in epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and breast cancer metastasis was identified from mouse metastatic model cell lines (11, 12). Unfortunately, there are very few overlapping gene targets between those previously identified gene groups (13). This may reflect differences in experimental systems and analysis strategies employed in those studies. As a result, the lack of common targets has posed a major challenge for understanding the biological groundwork of breast cancer metastasis, and has impeded the development of targeted therapies. In this regard, a new experimental strategy is urgently needed for the identification of essential contributor genes underlying breast cancer metastasis.

In this study, we report a cross-species (mouse and human metastatic model cell lines) expression profiling strategy to identify gene targets in breast cancer metastasis. A multigenic program consisting of 22 up-regulated and 12 down-regulated genes was identified. The correlation of all gene expression levels and metastasis potential were confirmed in human and mouse cancer cell lines. We then focused on Foxq1, a forkhead-box-containing transcription factor, and further investigated its role in cell proliferation, colony formation, cell migration, and invasion in vitro and in long-distance metastasis using a xenograft experimental mouse model. Moreover, we showed that altered expression of Foxq1 led to EMT or mesenchylmal–epithelial transition (MET). We further showed that Foxq1 transcriptionally repressed E-cadherin by directly binding to the E-box in its promoter region. Finally, we observed that TGFβ1 treatment led to the upregulation of Foxq1. Knockdown of Foxq1 blocked EMT induced by TGFβ1 treatment at morphological and molecular levels.

Materials and Methods

Cell cultures

Mouse breast cancer cell lines 4T1, 168FARN, and 67 NR were originally generated by one of the authors (FRM) and have been characterized for their metastasis capability in vivo (14). These cells were cultured in high glucose DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS, 5% NCS, NEAA, and antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin). All human breast cancer cell lines and MDCK cell were obtained from and characterized by cytogenetic analysis by American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). All these cell lines were grown by ATCC recommendations. The mouse mammary epithelial cell line EpRas and the human mammary epithelial cell line HMLE were obtained from Robert A. Weinberg's laboratory at MIT. EpRas was maintained in DMEM, 8% FBS and 500 µg/mL G418. The HMLE was maintained in the culture as described (15). Both cell lines were authenticated upon receiving by comparing to the original morphological and growth characteristics (11). The existences of the Ha-Ras oncogene in EpRas cell and the SV40 large T antigen and a catalytic subunit of telomerase in HMLE cell were confirmed by PCR.

Microarray analysis

The RNA from the optimized culture condition was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and purified with an RNA purification kit (Qiagen). Twenty-five nanograms of RNA was labeled with dye and applied to the microarray. Changes in gene expression were analyzed using a Sentrix human and mouse Ref-8 Expression BeadChip (Illumina, 8 array "stripes"). Data were normalized using the "average" method that simply adjusts the intensities of the 2 populations of gene expression values such that the means of the populations become equal. Fold enrichment values were used to obtain the list of candidates with greater than a 2-fold change.

RT-PCR and quantitative real time PCR

Regular RT-PCR was performed as previously described (16). Briefly, a total of 1 µg of RNA from each cell line was used to generate single-strand cDNA with random hexamer primers using the Superscript II first strand synthesis system for RT-PCR (Invitrogen). Quantitative RT-PCR was done using the iQSYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). A GAPDH primer set was used as an internal control.

Generation of expression constructor and lentivirus

A full-length Foxq1 plasmid was purchased from Open Bio-systems. The Foxq1 gene was then subcloned into a pEntry vector and recombinated into a pLenti-6 Vector. A set of 5 shRNA clones for Foxq1 was purchased from Open Biosystems. The lentivirus for the full length and shRNA of Foxq1 were then generated using the pLentivirus-expression system (Invitrogen) and the Trans-Lentiviral packaging system (Open Biosystems). It was then used to infect the targeted model cell. Stable cells were generated after being selected with Blasticidin (10 µg/mL) or puromycin (12 µg/mL) (Invivogen) for 20 days.

Cell proliferation, colony formation assay, in vitro migration, and invasion assays

These assays were performed as described previously (17).

In vivo metastasis assay

The EpRas-derived tumor cells (2 × 105) in 100 µL PBS were injected into the mammary gland of 5-week-old female NCR Nu/Nu mice that were purchased from Taconic. The 4T1-derived tumor cells (2 × 104) in 50 µL were injected into the mammary glands of 5-week-old female BALB/C mice that were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Post tumor cell injections, mice were sacrificed at the fourth week. The mammary tumor and lungs were removed and embedded into paraffin blocks. Standard hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of paraffin-embedded tissue was performed for histological examination of metastases.

Luciferase reporter assay

The 233 bp (−108 to +125) E-cadherin promoter sequence (wild type) and the mutant form (with 3 E-box mutations) were purchased from Addgene Company. The other 6 mutant form E-cadherin promoters were generated using the STRA-TAGENE QUIKCHANGE kit.

293F T or MCF7 cells were plated at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well in 24-well plates and were grown overnight prior to transfection. All transfections were carried out using Fugene-6 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) and were done in duplicate and repeated at least 3 times. Luciferase assays were done using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

A Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Kit (Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions) was used for chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis according to the manufacturer's protocol. The anti-V5 antibody (Invitrogen) was used for immunoprecipitation. PCR consisted of 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s using Taq polymerase (Invitrogen). The PCR primers used for ChIP were as follows: CDH1CHIP L: CTG TGG CCG GCA GGT GAA C; CDH1 CHIP R: CAA GCT CAC AGG TGC TTT GC.

Statistical analysis

A 2-sided independent Student's t-test without equal variance assumption was performed to analyze the results of cell growth, colony formation, cell migration and invasion, Luci-ferase assay, tumor burdens, and tumor metastasis results.

Results

Identification of the multigenic program involved in breast cancer cell metastasis using a comparative expression profiling strategy

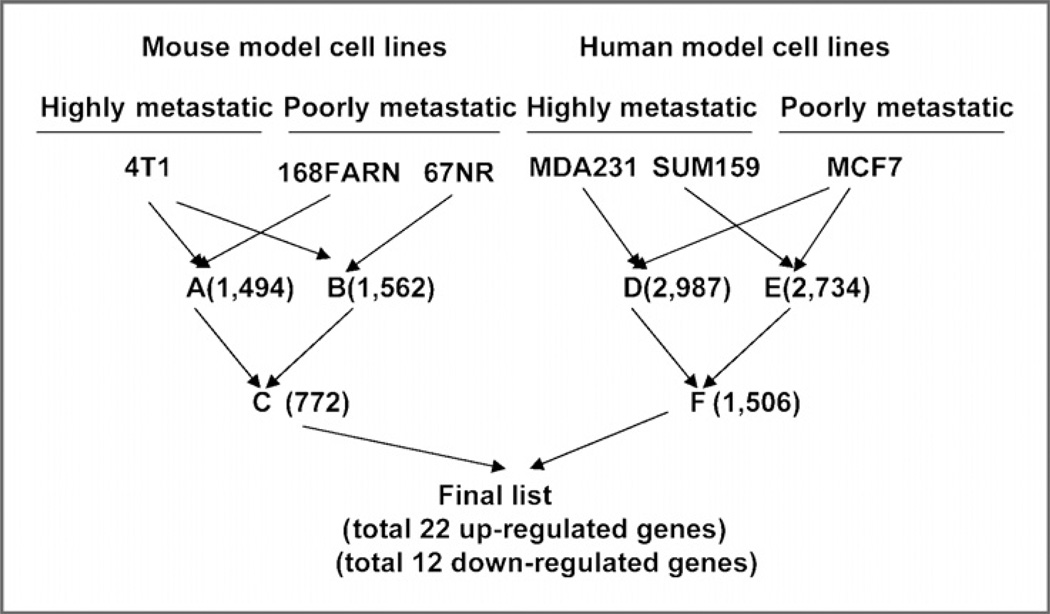

In our study, 4T1 is used as a highly metastatic mouse cell model. 168FARN and 67NR are used as poorly metastatic mouse models (14). In parallel, 2 highly metastatic human breast cancer cell lines-–MDA-MB-231 and SUM159, and the poorly metastatic MCF7-–were also used in our study (18). We then performed the algorithm indicated in the flowchart to obtain the final candidate genes for further analysis (Fig. 1). A total of 22 up-regulated and 12 down-regulated genes were obtained through comparison of the final gene lists from mouse and human genomes. These 2 gene groups were shown with an expression markedly changed (with more than 2-fold difference) in highly metastatic cell lines compared to poorly metastatic cell lines (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

Figure 1.

Identification of genes involved in breast cancer metastasis. The schematic representation of the research strategy for cross-species integrative expression profiling. The numbers indicate the differentially expressed genes after each comparison. Differential expression was calculated for the highly metastatic cell line versus the poorly metastatic cell line data sets using an algorithm provided by Bead Studio. Fold enrichment values were used to obtain the list of candidates with greater than a 2-fold change.

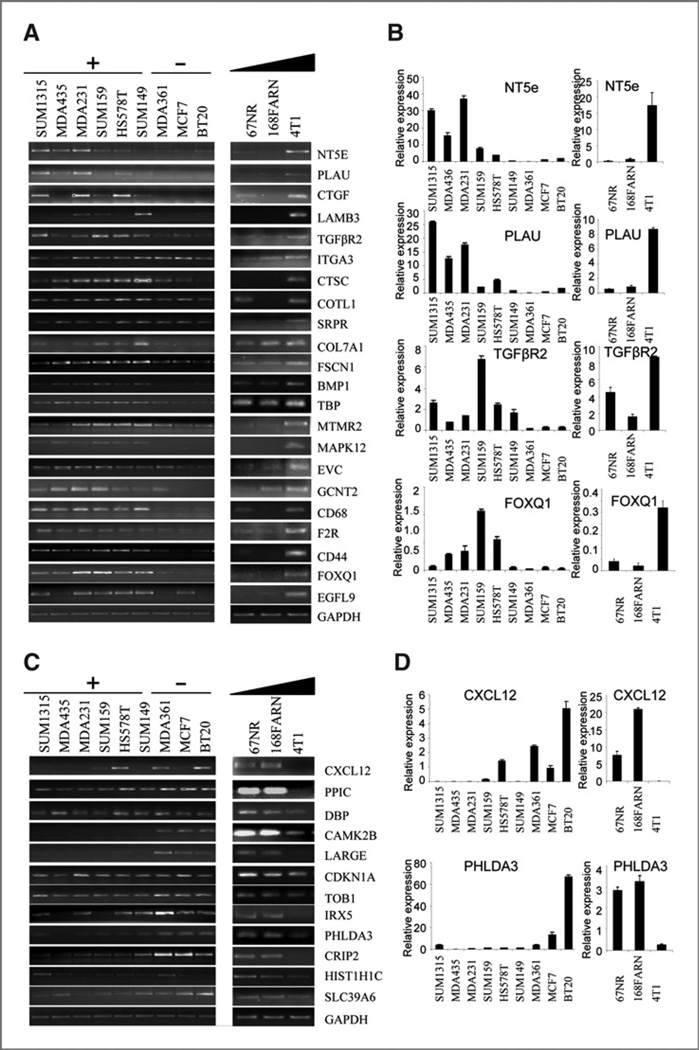

Among the identified genes with various biological functions, many were recognized as well-known genes that played critical roles in cancer metastasis. These genes include ECM and adhesion-related proteins such as PLAU (19, 20), COL7A1, ITGA3, and LAMB3 (21–23). They also include several growth factors, chemokines, and receptors, including Tgfbr2 (24, 25), CTGF (26, 27), CXCL12 (28, 29), and BMP1 (30), as well as the stem cell marker CD44 (31, 32). About half of the gene candidates are novel and their roles in metastasis have not been reported (Supplementary Table S3). The expression pattern of the candidate genes in the human and mouse model cell lines are confirmed by regular RT-PCR and quantitative real time RT-PCR (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. S1–S3). We specifically checked the expression pattern of all gene candidates in a broader set of human breast cancer cell lines with different metastatic capabilities. We found that 18 out of 22 up-regulated genes were undetectable or had low expression in all 3 poorly metastatic cell lines. Almost all the genes showed high expression in more than 4 out of the 6 highly metastatic cancer cell lines. In addition, 9 out of 12 down-regulated genes were expressed in poorly metastatic cells and 8 out of 12 genes showed no or low expression in at least 4 out of 6 highly metastatic breast cancer cell lines.

Figure 2.

Confirmation of the microarray results. RT-PCR and quantitative real-time RT-PCR results show the expression pattern of up-regulated genes (A and B) and down-regulated genes (C and D) in a panel of human breast cancer cells (A and C left panels) and mouse model cell lines (A and C right panels). Gene names are shown to the right of the panels. GAPDH is used as an RNA loading control. +, highly metastatic; −, poorly metastatic. The triangular bar indicates the increase of metastasis. Panels B and D show quantitative real-time RT-PCR results for selected genes.

In this study, we specifically chose the transcription factor Foxq1 as a candidate gene for further biological and functional analysis, because a few transcription factors, including a Forkhead-Box gene family member Foxc2, have been found involved in breast cancer metastasis. Overexpression of Foxq1 was initially found in 4T1 cells, as well as MDA-MB231 and SUM159 cells (Supplementary Table S1). The expression pattern was also confirmed by RT-PCR, quantitative real-time RT-PCR, and a western blotting assay in both human and mouse cell lines (Fig. 2A and B and Supplementary Fig. S4A and B). Nucleus localization of Foxq1 was also confirmed by an immunofluorescence assay (Supplementary Fig. S4C).

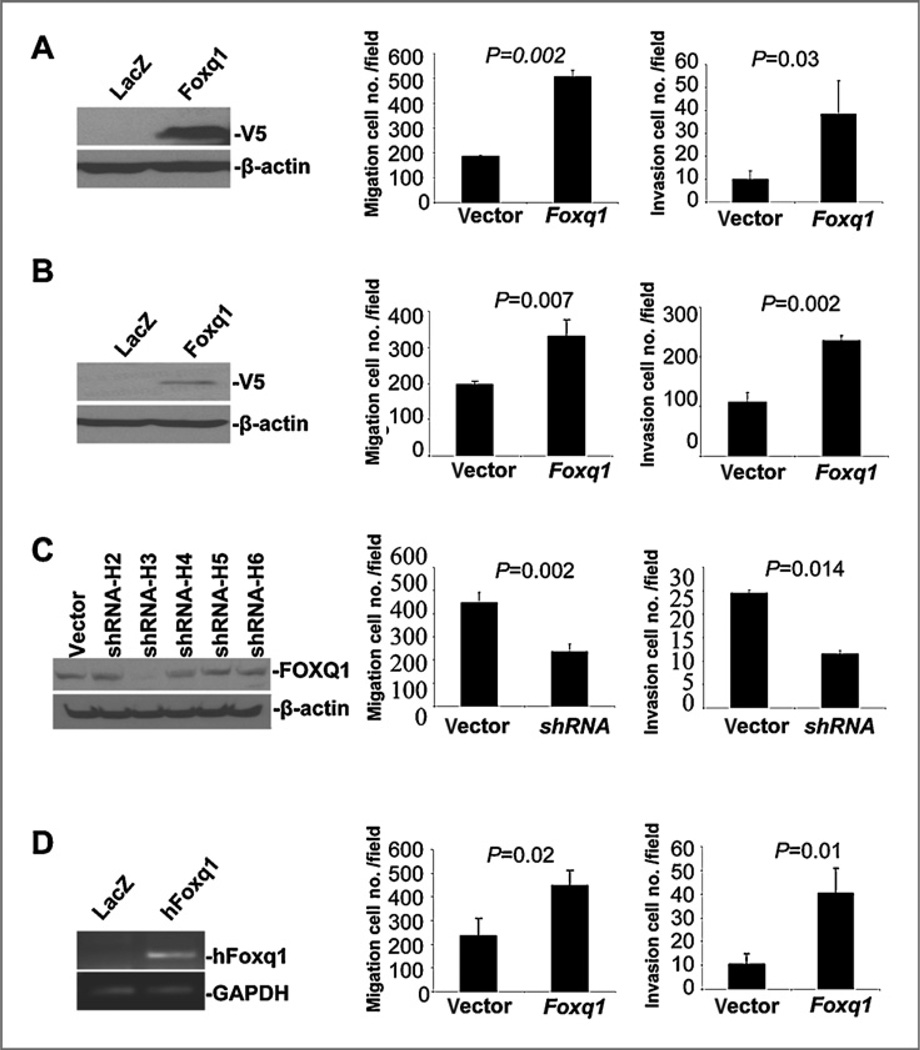

Foxq1 contributes to cell invasion and cell migration in vitro

To investigate the function of Foxq1 in metastasis, we first tried to establish model cell lines with ectopic expression of Foxq1. Unfortunately, ectopic expression of Foxq1 resulted in significant cell death in a variety of epithelial cell lines, including MCF7, BT20 cells (unpublished data). We then chose the human mammary epithelial cell HMLE, and mouse mammary epithelial cell EpRas to establish the stable cell lines (Fig. 3A and B). These 2 cell lines were popularly used in breast tumorigenesis and metastasis studies (11, 12). We also established a model cell line with Foxq1 knockdown based on the highly metastatic mouse 4T1 cell line using a shRNA technique (Fig. 3C). Cell proliferation and colony formation were first studied using these cell models. We found that no significant difference was observed between these model cell lines and their vector control counterparts for all model cell lines (Supplementary Figs. S5–S7).

Figure 3.

Foxq1 promotes cell invasion and migration in vitro. A and B, the ectopic expression of Foxq1 (left), migration (middle), and invasion (right) assay shows that the ectopic expression of Foxq1 leads to an increase in cel migration and an increase in cell invasion in HMLE cells (A) and in EpRas cells (B). C, the shRNA knockdown of Foxq1 (left), migration (middle), and invasion (right) assay shows that the knockdown of Foxq1expression leads to a decrease in migration (P= 0.002) and invasion ability (P= 0.014) in 4T1 cells. D, the expression of human Foxq1 (left), migration (middle), and invasion (right) assay shows that the expression of hFoxq1 leads to an increase in migration (P= 0.002) and invasion ability (P= 0.014) in 4T1 cells with mFoxq1 knockdown. All experiments were performed in triplicate. The data number was the mean value from 5 randomly selected field views. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean).

We then investigated the effect of Foxq1 on cell migration and invasion using the chamber assay. We observed that HMLE cells with ectopic expression of Foxq1 had a significant increase in cell migration (2.5-folds, P = 0.002) and invasion (4-folds, P = 0.03) (Fig. 3A, middle and right panel and Supplementary Fig. S5). Similarly, ectopic expression of Foxq1 in EpRas led to increased cell migration (1.5-folds, P = 0.007) and cell invasion (2.2-folds, P = 0.002) (Fig. 3B, middle and right panels and Supplementary Fig. S6). Knockdown of Foxq1 expression in 4T1 cells led to a marked decrease in cell migration (48%, P = 0.002) and invasion (53%, P = 0.014) (Fig. 3C, middle and right panels and Supplementary Fig. S7). Moreover, we performed a rescue experiment by introducing hFoxq1 into 4T1 cells with mFoxq1 knockdown (Fig. 3D). We found that introduction of hFoxq1 did not change cell proliferation (Supplementary Fig. S7E), but led to an increase in cell migration (2-folds, P = 0.02) and invasion (4-folds, P = 0.01) (Fig. 3D, middle and right panels).

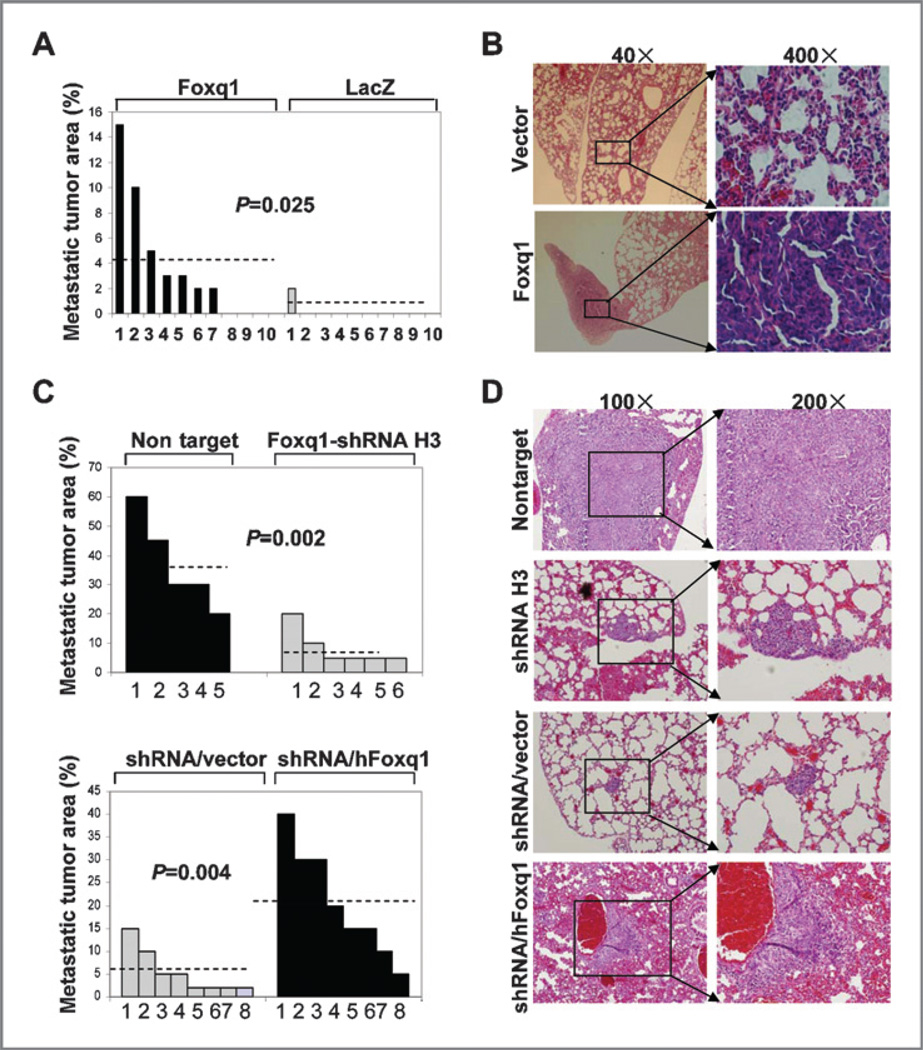

The effect of overexpression and knockdown of Foxq1 on long-distance metastasis in vivo

We next examined the effects of the Foxq1 gene on longdistance metastasis in vivo. EpRas cells expressing either control vector or Foxq1 were injected into the mammary gland of nude mice and their lungs were examined for metastasis 4 weeks after injection. Detailed quantification was conducted with H&E staining on the lung sections. In 7 out of 10 lung sections from mice injected with EpRas cells overexpressing Foxq1, tumor areas made up about 2% to 15% of the sections. On the other hand, in lung sections from 10 mice injected with the EpRas cell expressing control vector, only one case showed a 2% tumor area in the entire sections (Fig. 4A and B). It is worth mentioning that the tumor burden in the control vector group and the Foxq1 overexpression group had no significant difference during the 4 weeks (Supplementary Fig. S8).

Figure 4.

Foxq1 promotes longdistance metastasis in vivo. A and C, quantification of metastasis in vivo. A, two populations of EpRas cells with the vector (LacZ) or the Foxq1 gene were injected in 10 mice, respectively. C, 4T1 cells with nontarget control and Foxq1 shRNA H3 were injected in 5 and 6 mice, respectively (top panel). 4T1/shRNA cells with vector and hFoxq1 expression were used in 8 mice, respectively (bottom panel). B and D, representative H&E staining pictures of lung sections from mice injected with genetically modified EpRas (magnification, 40× and 400×) or 4T1-derived cells (magnification, 100× and 200×). For both panels, the origins of the lung sections are indicated on the left side of the panels.

To further validate the role of Foxq1 in long-distance metastasis, 4T1 derivative cells with Foxq1 knockdown and a nontarget control were injected into the fat pads of BALB/C mice. We observed that 4T1 cells with a nontarget control have a similar metastatic propensity as the parental 4T1 cells (30–40%), which showed an average of 37% metastasis loci in the lung section. In contrast, the 4T1 cells with Foxq1 knockdown showed an average of 8.3% metastatic loci in the lung section [Fig. 4C (top panel) and D, P = 0.002). In addition, we did not observe a significant difference in tumor burdens between 4T1 cells with Foxq1 knockdown and nontarget control (data not shown). Moreover, expression of hFoxq1 in 4T1 cells with mFoxq1 knockdown showed an average of 20.5% metastatic loci in the lung section [Fig. 4C (bottom panel) and D, P = 0.004], indicating the reconstitution of the metastatic ability of 4T1 cells.

Foxq1 is actively involved in EMT in epithelial cell lines

We next used established model cell lines to investigate the effect of Foxq1 on the EMT process. Ectopic expression of Foxq1 in HMLE cells led to marked EMT, which is demonstrated by a more spindle-like, scattered distribution in HMLE/Foxq1 cells, and a more cobblestone-like appearance in HMLE/LacZ control cells (Fig. 5A). This morphological alteration is accompanied by the downregulation of epithelial cell markers E-cadherin, β-catenin, and γ-catenin and upre-gulation of mesenchymal markers Fibronectin, Vimentin, and N-cadherin (Fig. 5B). This data were confirmed with an immunofluorescence assay using the same cell lines (Fig. 5C). In addition, overexpression of Foxq1 caused a reduced level of E-cadherin, and no alterations in other epithelial and mesenchymal markers and morphological change was observed in the MDCK cell line (Supplementary Fig. S9). Meanwhile, an increase in cell migration—but not cell proliferation and colony formation—was observed due to the ectopic expression of Foxq1 in MDCK cells (Supplementary Fig. S10).

Figure 5.

The effect of Foxq1 on the EMT program in human mammary epithelial cells. A, representative pictures show the morphological change after ecotopic expression of Foxq1 in HMLE cell. B, Western blotting results show the effect of ectopic expression of Foxq1 on EMT markers. C, an immunofluorescence assay confirmed the results of the Western blot in HMLE cells. The green signal represents the staining of the corresponding protein, and the blue signal represents the HOECHST 33342-stained nuclei.

We further observed that downregulation of Foxq1 led to a significant cellular morphological change from mesenchymal to epithelial transition (MET) in 4T1 cells (Supplementary Fig. S11A). We also found that the downregulation of Foxq1 caused an increase in expression of epithelial marker E-cadherin and β-catenin and a decrease in expression of mesenchymal marker Vimentin (Supplementary Fig. S11B and C).

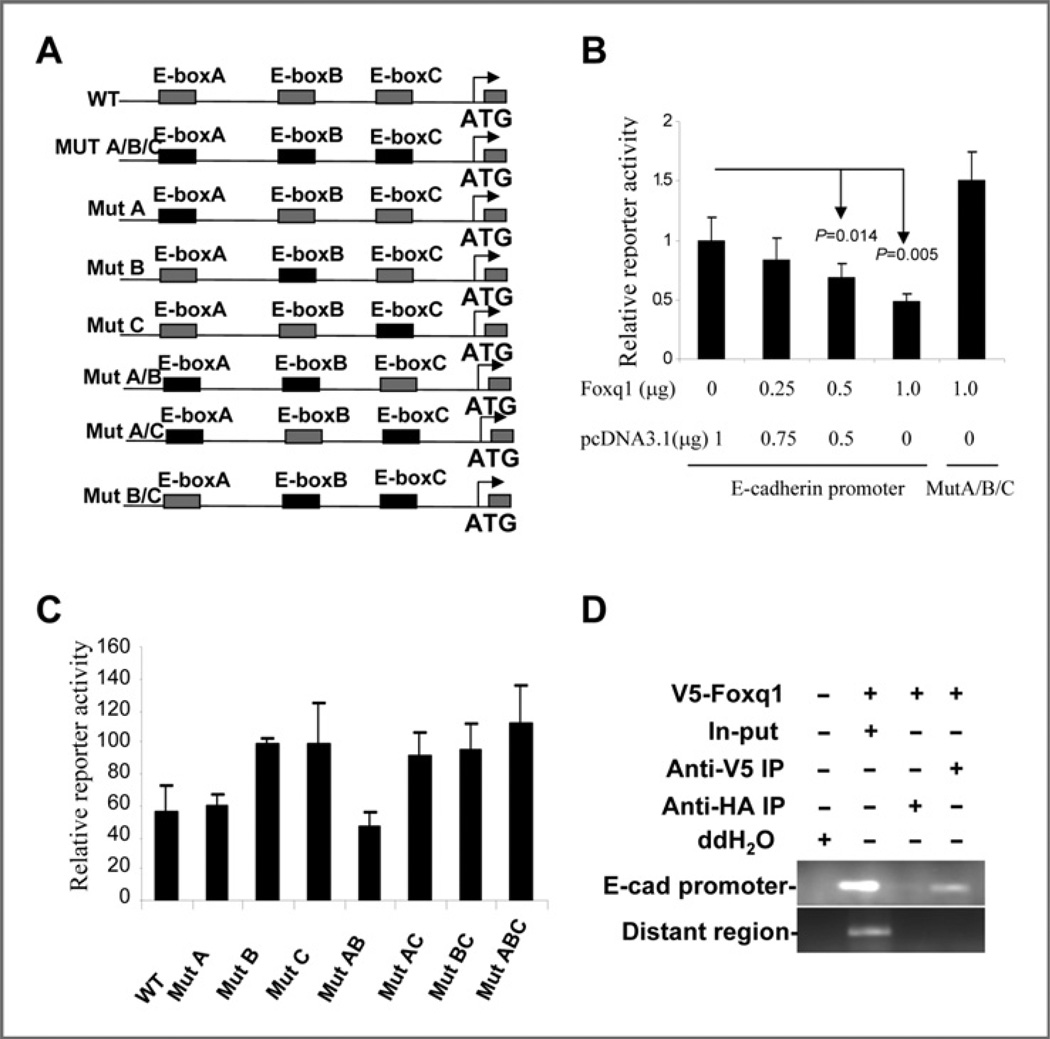

Foxq1 transcriptionally regulate E-cadherin

We next performed a Luciferase reporter assay to investigate whether Foxq1 can transcriptionally regulate the E-cad-herin gene. The relative Luciferase activity of E-cadherin was found to decrease proportionally to increasing amounts of Foxq1 in 293FT cells (Fig. 6B) and MCF7 cells (Supplementary Fig. S12). To further clarify the Foxq1-responsive elements in the E-cadherin promoter, we focused on the 3 E-boxes, which confer response to several well-known metastasis- and EMT-promoting genes. Seven different mutant reporter constructs with specific sequence change in the E-box were generated (Fig. 6A and Supplementary Fig. S13). We then compared the ability of Foxq1 to repress different reporter constructs that carried combinations of mutated E-box sites. Results from these experiments led us to conclude that the 3 E-boxes cooperate in Foxq1-mediated E-cadherin repression. The third E-box is the most important because whenever it is coupled with first and second mutants, it would yield the strongest responsive activity (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, we carried out CHIP assays to determine the direct interaction between the FOXQ1 protein and the E-box in the E-cadherin promoter. In agreement with above, we found that Foxq1-V5 directly interacted with the E-cadherin promoter region spanning the E-box (Fig. 6D). The association was specific to Foxq1, because the E-cadherin promoter was undetectable in nonspecific anti-HA antibody IP and in a PCR with a pair of primers located in a distant region away from the E-box region in the promoter. Consistent with this, a perfect reverse correlation of the expression of Foxq1 and E-cadherin was observed in a set of breast cancer cell lines (Supplementary Fig. S14).

Figure 6.

Transcriptional regulation of E-cadherin by . A, schematic representation of the Luc-reporter construction, showing location of the 3 E-boxes in the promoter region of E-cadherin gene. The black boxes show the mutant form. B, Foxq1 downregulates the E-cadherin promoter in a dose-dependent manner. Samples 1–4, which show variable amounts of the Foxq1 expression construct and pcDNA3.1 vector, were cotransfected into 293FT cells with the E-cadherin promoter plasmid. Bars, SD. C, mutation of the E-boxes impairs repression of the E-cadherin promoter by Foxq1. Data are expressed as Luc activity in the presence of Foxq1 as a percentage of the activity of the same reporter in the presence of the control vector. Bars, SD. D, direct interaction between Foxq1 and the E-cadherin promoter. Anti-V5 coprecipitated chromatin was subjected to E-cadherin promoter-specific PCR amplification. PCR amplification from the total chromatin (Input, lane 2) was used as a positive control and those lacking Foxq1 expression (lane 1) or anti-HA (lane 3) and a pair of primers located in a distant region of E-cadherin promoter (bottom panel) served as diverse negative controls.

Foxq1 is involved in TGF-β signaling-induced EMT

To investigate whether Foxq1 is involved in TGF-β signaling, a well-known signaling that activates EMT and promotes metastasis in the later stages of tumorigenesis (33–36), we treated the EpRas cell with 1 ng/mL TGF-β1 and found an increase of Foxq1 gene expression, as well as Foxc2 gene expression, occurred within 5 days (Fig. 7A). We then knocked down Foxq1 expression in EpRas cells with shRNA. The shRNA-H5 clone showed a significant decrease of Foxq1 expression and the shRNA-H4 clone showed a minor decrease of Foxq1 (Fig. 7B). These 2 clones, along with nontarget control cells, were then treated with TGF-β1. We found that TGF-β1 induced significant EMT in nontarget control cells within 4 days, but not in shRNA-H5 clone cells (Fig. 7C). In addition, treatment of the shRNA-H4 clone cells with TGF-β1 showed minor change of EMT (data not shown). Consistent with what is described earlier, E-cadherin expression was inhibited and N-cadherin expression was increased in nontarget cells with TGF-β1 treatment. However, E-cadherin expression is not changed and N-cadherin expression has only a weak induction in shRNA-H5 clone cells. All these results indicated that Foxq1 is involved in and required for TGF-β1 induced EMT.

Figure 7.

Foxq1 is involved in TGF-β1 signaling. A, induction of Foxq1 by TGF-β1. EpRas cells were treated with 1 ng/mL TGF-β1 in 5 days. Foxq1 expression is confirmed by RT-PCR (top panel) and real time RT-PCR (bottom panel). Foxc2 is a positive control. B, knockdown of Foxq1 in EpRas cells with shRNA was confirmed by RT-PCR (top panel) and real time RT-PCR (bottom panel). C, representative pictures show the morphological change after treatment of TGF-β1 in EpRas cells with nontarget vector and shRNA-H5. D, Western blotting results show the effect of Foxq1 on EMT markers after TGF-β1 treatment.

Discussion

Our study represents the first application of the cross-species expression profiling approach used to identify critical metastasis-related genes. One possible concern is that the comparison of MDA-MB 231, SUM159, and MCF7 cell lines may reflect not only the differences in metastasis capability of these cell lines, but also the different characteristics of basal versus luminal tumors. With this in mind, we specifically designed the mutual filter of the human and mouse model cell lines to maximally decrease this possibility. The identification of a list of well-known metastatic gene signatures in our study (Supplementary Table S3) demonstrates the feasibility and power of this research strategy in identifying metastasis-related genes. However, for the novel genes such as Foxq1, direct biological and functional evidences are needed to clarify their roles as metastasis-related genes.

Foxq1 belongs to the human Forkhead-Box (Fox) gene family, which consists of at least 43 members. The Fox gene family encodes transcription factors containing an approximately 100 amino acid, DNA-binding domain known as the forkhead box. Deregulation of the Fox family genes, caused by various mechanisms such as mutation, amplification, and gene fusion, leads to congenital disorders, diabetes mellitus, or carcinogenesis (37). Many Fox family genes play important roles in vertebrate development. Specifically, Foxq1 has been suggested to be a downstream mediator of Hoxa1 in embryonic stem cells and shown to be regulated by Hoxc13 during hair follicle development (38, 39). Moreover, overexpression of Foxq1 has been reported in several cancers including lung carcinoma cell lines, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (40, 41), and in the transition from normal intestinal epithelium to adenoma and carcinomas in an APC min/+ mouse (42). Consistent with our report, Foxq1 was discovered as one of the TGF-β responsive genes in TβRII mammary carcinoma cells (43). Our results revealed for the first time that Foxq1, like other developmental genes such as snail, twist, and Zeb1/2, is also a critical mediator of EMT and breast cancer metastasis. Thus, Foxq1 has joined the multigenic program and has become one of the few transcription factors involved in both development and cancer metastasis.

Coincidently, a recent report showed overexpression of Foxq1 in colorectal cancer and that ectopic expression of Foxq1 could promote an antiapoptotic effect and enhance tumorigenicity and tumor growth (44). The discrepancy between the results regarding Foxq1 in colon and breast cancers may reflect the distinct functions of one gene in various human cell lines and cancers with different genetic backgrounds. Furthermore, ectopic expression of Foxq1 resulted in significant cell death in a variety of epithelial cell lines, including MCF7 and BT20 cells in our study (unpublished data). However, overexpression of Foxq1 promotes EMT and metastasis in various epithelial cell lines. A similar contradictory phenomenon is frequently reported for several other genes including Foxc2 and Dab2 (45), suggesting that Foxq1 and similar genes may act like TGF-β, which harbors dual functions in tumor progression. Further study of the mechanism underlying this phenomenon may result in an effective approach to target TGF-β signaling and metastasis in breast cancer.

Our study showed that Foxq1 repressed E-cadherin expression by targeting the E-box in its promoter region. E-cadherin plays a critical role in cell adhesion, development of epithelial organs and the establishment/maintenance of epithelial polarity (46). The progression of benign tumors to invasive metastatic cancer involves partial or complete loss of E-cadherin expression, or an impairment of its adhesive function (47). Direct transcriptional repression of E-cadherin was reported for transcription factors such as Slug/Snail (48). However, it is uncommon for a Fox family transcription factor to bind to E-box sequences directly. Whether there are other Fox family genes behave like this is worthy of further investigation. Meanwhile, our result does not exclude the possibility that Foxq1 represses E-cadherin through regulating other EMT promoting genes, because mutual regulation is very common between the EMT promoting genes (49). More important, we also revealed that Foxq1 is involved in TGF-β signaling. Knockdown of Foxq1 blocked TGF-β1 induced EMT. Thus, the TGFβ/Foxq1/E-cadherin axis could serve as a novel signaling pathway driving breast cancer progression. Further exploration of Foxq1 downstream targets as well as their function in vivo with animal models will provide new insight into the critical role of the Foxq1 gene as a therapeutic target for metastatic breast cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Robert A. Weinberg's laboratory at MIT for providing technical advice and the HMLE and EpRas cell lines. We also want to thank Elizabeth A. Katz of the Karmanos Cancer Institute's Marketing & Communications Department for editing our manuscript.

Grant Support

This work was supported in part by the Susan G. Komen grant KG080465 (G. Wu) and a pilot grant from the Karmanos Cancer Institute, Wayne State University (G. Wu). The Biostatistic Core and the Biorepository Core of Karmanos Cancer Institute are supported by grant number P30-CA022453–29.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Research Online (http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

Microarray data reported herein have been deposited at the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus with the accession number GSE25972(50).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eccles SA, Welch DR. Metastasis: recent discoveries and novel treatment strategies. Lancet. 2007;369:1742–1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60781-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicolini A, Giardino R, Carpi A, Ferrari P, Anselmi L, Colosimo S, et al. Metastatic breast cancer: an updating. Biomed Pharmacother. 2006;60:548–556. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2006.07.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steeg PS. Tumor metastasis: mechanistic insights and clinical challenges. Nat Med. 2006;12:895–904. doi: 10.1038/nm1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van de Vijver MJ, He YD, van't Veer LJ, Dai H, Hart AA, Voskuil DW, et al. A gene-expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1999–2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van 't Veer LJ, Dai H, van de Vijver MJ, He YD, Hart AA, Mao M, et al. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature. 2002;415:530–536. doi: 10.1038/415530a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Klijn JG, Zhang Y, Sieuwerts AM, Look MP, Yang F, et al. Gene-expression profiles to predict distant metastasis of lymph-node-negative primary breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:671–679. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17947-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang Y, Siegel PM, Shu W, Drobnjak M, Kakonen SM, Cordon-Cardo C, et al. A multigenic program mediating breast cancer metastasis to bone. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:537–549. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minn AJ, Gupta GP, Siegel PM, Bos PD, Shu W, Giri DD, et al. Genesthat mediate breast cancer metastasis to lung. Nature. 2005;436:518–524. doi: 10.1038/nature03799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minn AJ, Kang Y, Serganova I, Gupta GP, Giri DD, Doubrovin M, et al. Distinct organ-specific metastatic potential of individual breast cancer cells and primary tumors. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:44–55. doi: 10.1172/JCI22320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mani SA, Yang J, Brooks M, Schwaninger G, Zhou A, Miura N, et al. Mesenchyme Forkhead 1 (FOXC2) plays a key role in metastasis and is associated with aggressive basal-like breast cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10069–10074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703900104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, Ramaswamy S, Itzykson RA, Come C, et al. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 2004;117:927–939. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu G, Chong RA, Yang Q, Wei Y, Blanco MA, Li F, et al. MTDH activation by 8q22 genomic gain promotes chemoresistance and metastasis of poor-prognosis breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aslakson CJ, Miller FR. Selective events in the metastatic process defined by analysis of the sequential dissemination of subpopulations of a mouse mammary tumor. Cancer Res. 1992;52:1399–1405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morel AP, Lievre M, Thomas C, Hinkal G, Ansieau S, Puisieux A. Generation of breast cancer stem cells through epithelial-mesench-ymal transition. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang H, Chen D, Ringler J, Chen W, Cui QC, Ethier SP, et al. Disulfiram treatment facilitates phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibition in human breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3996–4004. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang H, Liu G, Dziubinski M, Yang Z, Ethier SP, Wu G. Comprehensive analysis of oncogenic effects of PIK3CA mutations in human mammary epithelial cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;112:217–227. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9847-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuperwasser C, Dessain S, Bierbaum BE, Garnet D, Sperandio K, Gauvin GP, et al. A mouse model of human breast cancer metastasis to human bone. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6130–6138. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duffy MJ, Maguire TM, McDermott EW, O’Higgins N. Urokinase plasminogen activator: a prognostic marker in multiple types of cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1999;71:130–135. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199906)71:2<130::aid-jso14>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stephens RW, Brunner N, Janicke F, Schmitt M. The urokinase plasminogen activator system as a target for prognostic studies in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998;52:99–111. doi: 10.1023/a:1006115218786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kita Y, Mimori K, Tanaka F, Matsumoto T, Haraguchi N, Ishikawa K, et al. Clinical significance of LAMB3 and COL7A1 mRNA in esopha-geal squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurokawa A, Nagata M, Kitamura N, Noman AA, Ohnishi M, Ohyama T, et al. Diagnostic value of integrin alpha3, beta4, and beta5 gene expression levels for the clinical outcome of tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2008;112:1272–1281. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oka T, Yamamoto H, Sasaki S, Ii M, Hizaki K, Taniguchi H, et al. Overexpression of beta3/gamma2 chains of laminin-5 and MMP7 in biliary cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3865–3873. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muraoka-Cook RS, Dumont N, Arteaga CL. Dual role of transforming growth factor beta in mammary tumorigenesis and metastatic progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:937s–943s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan AR, Alexe G, Reiss M. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling: emerging stem cell target in metastatic breast cancer? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:453–495. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0184-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chu CY, Chang CC, Prakash E, Kuo ML. Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and cancer progression. J Biomed Sci. 2008;15:675–685. doi: 10.1007/s11373-008-9264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu LY, Han YC, Wu SH, Lv ZH. Expression of connective tissue growth factor in tumor tissues is an independent predictor of poor prognosis in patients with gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2110–2114. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wendt MK, Drury LJ, Vongsa RA, Dwinell MB. Constitutive CXCL12 expression induces anoikis in colorectal carcinoma cells. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:508–517. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou W, Jiang Z, Liu N, Xu F, Wen P, Liu Y, et al. Down-regulation of CXCL12 mRNA expression by promoter hypermethylation and its association with metastatic progression in human breast carcinomas. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:91–102. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0435-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen D, Zhao M, Mundy GR. Bone morphogenetic proteins. Growth Factors. 2004;22:233–241. doi: 10.1080/08977190412331279890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dontu G, Liu S, Wicha MS. Stem cells in mammary development and carcinogenesis: implications for prevention and treatment. Stem Cell Rev. 2005;1:207–213. doi: 10.1385/SCR:1:3:207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marhaba R, Zoller M. CD44 in cancer progression: adhesion, migration and growth regulation. J Mol Histol. 2004;35:211–231. doi: 10.1023/b:hijo.0000032354.94213.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Derynck R, Jarrett JA, Chen EY, Eaton DH, Bell JR, Assoian RK, et al. Human transforming growth factor-beta complementary DNA sequence and expression in normal and transformed cells. Nature. 1985;316:701–705. doi: 10.1038/316701a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grunert S, Jechlinger M, Beug H. Diverse cellular and molecular mechanisms contribute to epithelial plasticity and metastasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:657–665. doi: 10.1038/nrm1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miettinen PJ, Ebner R, Lopez AR, Derynck R. TGF-beta induced transdifferentiation of mammary epithelial cells to mesenchymal cells: involvement of type I receptors. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:2021–2036. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rahimi RA, Leof EB. TGF-beta signaling: a tale of two responses. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102:593–608. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katoh M. Human FOX gene family (Review) Int J Oncol. 2004;25:1495–1500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinez-Ceballos E, Chambon P, Gudas LJ. Differences in gene expression between wild type and Hoxa1 knockout embryonic stem cells after retinoic acid treatment or leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) removal. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16484–16498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414397200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Potter CS, Peterson RL, Barth JL, Pruett ND, Jacobs DF, Kern MJ, et al. Evidence that the satin hair mutant gene Foxq1 is among multiple and functionally diverse regulatory targets for Hoxc13 during hair follicle differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29245–29255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bieller A, Pasche B, Frank S, Glaser B, Kunz J, Witt K, et al. Isolation and characterization of the human forkhead gene FOXQ1. DNA Cell Biol. 2001;20:555–561. doi: 10.1089/104454901317094963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cao D, Hustinx SR, Sui G, Bala P, Sato N, Martin S, et al. Identification of novel highly expressed genes in pancreatic ductal adenocarcino-mas through a bioinformatics analysis of expressed sequence tags. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:1081–1089. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.11.1175. discussion 90–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paoni NF, Feldman MW, Gutierrez LS, Ploplis VA, Castellino FJ. Transcriptional profiling of the transition from normal intestinal epithe-lia to adenomas and carcinomas in the APCMin/+ mouse. Physiol Genom. 2003;15:228–235. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00078.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bierie B, Chung CH, Parker JS, Stover DG, Cheng N, Chytil A, et al. Abrogation of TGF-beta signaling enhances chemokine production and correlates with prognosis in human breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1571–1582. doi: 10.1172/JCI37480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaneda H, Arao T, Tanaka K, Tamura D, Aomatsu K, Kudo K, et al. FOXQ1 is overexpressed in colorectal cancer and enhances tumorigenicity and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2053–2063. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prunier C, Howe PH. Disabled-2 (Dab2) is required for transforming growth factor beta-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17540–17548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500974200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gumbiner BM. Cell adhesion: the molecular basis of tissue architecture and morphogenesis. Cell. 1996;84:345–357. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Christofori G, Semb H. The role of the cell-adhesion molecule E-cadherin as a tumour-suppressor gene. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:73–76. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01343-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Batlle E, Sancho E, Franci C, Dominguez D, Monfar M, Baulida J, et al. The transcription factor snail is a repressor of E-cadherin gene expression in epithelial tumour cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:84–89. doi: 10.1038/35000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peinado H, Olmeda D, Cano A. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour pRogression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrc2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu G. [database on the Internet] Bethesda MD: National Library of Medicine US; c2010. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE25972. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.