Abstract

Hepatitis B vaccine has been available worldwide since the mid-1980s. This vaccine was evaluated in a clinical trial in Thailand, conducted on subjects born to hepatitis B surface antigen positive and hepatitis B e-antigen positive mothers and vaccinated according to a 4-dose schedule at 0, 1, 2 and 12 mo of age and a single dose of hepatitis B immunoglobulin concomitantly at birth. All enrolled subjects seroconverted and were followed for 20 y to assess the persistence of antibody to the hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs) (NCT00240539). At year 20, 64% of subjects had anti-HBs antibody concentrations ≥ 10 milli-international units per milli liter (mIU/ml) and 92% of subjects had detectable levels (≥ 3.3 mIU/ml) of anti-HBs antibodies. At year 20, subjects with anti-HBs antibody titer < 100 mIU/ml were offered an additional dose of hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccine to assess immune memory (NCT00657657). Anamnestic response to the challenge dose was observed in 96.6% of subjects with an 82-fold (13.2 to 1082.4 mIU/ml) increase in anti-HBs antibody geometric mean concentrations. This study confirms the long-term immunogenicity of the 4-dose regimen of the HBV vaccine eliciting long-term persistence of antibodies and immune memory against hepatitis B for up to at least 20 y after vaccination.

Keywords: hepatitis B, vaccine, challenge dose, persistence, hepatitis B virus

Introduction

Vaccination is a well-established, safe and effective method of conferring long-term protection against hepatitis B viral infections, liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) worldwide.1 Vaccination has resulted in a substantial decline in the hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related disease burden, prevalence of chronic HBV infections and HBV-related HCC among children and adolescents worldwide.2-5 Thailand adopted the policy of hepatitis B immunization in 1988, and universal hepatitis B vaccination of newborns has been integrated into the national expanded program of immunization since 1992.6 Available vaccines against hepatitis B have been shown to be safe and immunogenic.7

Mothers positive to hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and/or hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg) have a risk (70–90%) of chronically infecting their children.8-10 Three prospective studies were initiated in Thailand in 1986 to investigate the immunogenicity, reactogenicity and efficacy of a recombinant hepatitis B vaccine in children born to mothers that had different seropositivity status of HBsAg and HBeAg. The results of these trials have been published for several time-points up to year 20 after the first hepatitis B dose.8,9,11 This paper reports the persistence of antibodies against hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs) (NCT00240539) and anamnestic response to a hepatitis B vaccine challenge dose at the 20-y time-point (NCT00657657) in a cohort of subjects who had received a birth dose of hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIg) concomitantly with one dose of hepatitis B vaccine, followed by three additional doses at 1, 2 and 12 mo with no booster dose in the primary study.

Results

Demography

Of the 76 subjects in the primary study, 36 subjects returned for blood sampling at year 20. Among these, two subjects were boosted at year 5. Of the remaining 34 subjects, 25 subjects (unboosted group) were included in the long-term according-to-protocol (LT-ATP) cohort of immunogenicity and nine subjects were excluded at year 20 for the following reasons: not randomized to correct groups, due to which the study procedures might be different (n = 3); abnormal serology evolution, indicative of natural exposure to HBV (n = 4); and non-compliant with vaccination schedule (n = 2).

For the challenge phase, 29 subjects (from both boosted and unboosted groups) were included in the according-to-protocol (ATP) cohort for immunogenicity (3 subjects from year 18 and 26 subjects from year 19). Seven subjects had anti-HBs antibody concentrations ≥100 mIU/ml prior to challenge dose.

At year 20, the mean age of subjects in the LT-ATP cohort for immunogenicity was 19.6 y (standard deviation: 0.49 y); 16 (59.3%) were female and all subjects were of East/South East Asian origin.

Anti-HBs antibody persistence at year 20

At the post-primary time-point (month 13) all subjects had responded to the hepatitis B vaccine (i.e., 100% subjects had antibody titers above 10 mIU/ml). At year 20, 92.0% [95% confidence interval (CI): 74.0–99.0] of the subjects (23/25) had anti-HBs antibody concentration ≥3.3 mIU/ml. In addition, 64.0% (95% CI: 42.5–82.0) of subjects had anti-HBs antibodies ≥10 mIU/ml (Table 1).

Table 1. Anti-HBs antibody seroprotection rates and geometric mean concentrations post-primary vaccination (unboosted at year 5) at infancy until year 20 (LT-ATP cohort for immunogenicity).

| Time-Point (year) | N | S+ | ≥ 10 mIU/ml | GMC mIU/ml | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI [LL-UL] |

% | 95% CI [LL-UL] |

Value | 95% CI [LL-UL] |

||

| Post-primary | 54 | 100 | [93.4–100] | 100 | [93.4–100] | 4436.3 | [3084.7–6380.0] |

| 2 | 48 | 100 | [92.6–100] | 100 | [92.6–100] | 489.1 | [301.9–792.3] |

| 3 | 43 | 100 | [91.8–100] | 97.7 | [87.7–99.9] | 248.5 | [158.9–388.8] |

| 4 | 40 | 100 | [91.2–100] | 100 | [91.2–100] | 235.8 | [158.0–352.0] |

| 5 | 32 | 100 | [89.1–100] | 100 | [89.1–100] | 185.5 | [113.9–302.1] |

| 6 | 36 | 97.2 | [85.5–99.9] | 94.4 | [81.3–99.3] | 120.1 | [75.5–191.0] |

| 7 | 34 | 100 | [89.7–100] | 100 | [89.7–100] | 127.2 | [83.5–193.9] |

| 8 | 34 | 100 | [89.7–100] | 94.1 | [80.3–99.3] | 104.8 | [60.1–182.9] |

| 9 | 32 | 100 | [89.1–100] | 93.8 | [79.2–99.2] | 90.9 | [52.2–158.4] |

| 10 | 13 | 100 | [75.3–100] | 92.3 | [64.0–99.8] | 68.2 | [30.3–153.2] |

| 11 | 20 | 100 | [83.2–100] | 95.0 | [75.1–99.9] | 64.4 | [27.9–148.8] |

| 12 | 31 | 100 | [88.8–100] | 83.9 | [66.3–94.5] | 54.7 | [30.7–97.5] |

| 13 | 30 | 96.7 | [82.8–99.9] | 86.7 | [69.3–96.2] | 74.1 | [41.0–134.1] |

| 14 | 24 | 87.5 | [67.6–97.3] | 70.8 | [48.9–87.4] | 51.4 | [23.9–110.5] |

| 15 | 21 | 71.4 | [47.8–88.7] | 66.7 | [43.0–85.4] | 46.9 | [23.5–93.5] |

| 16 | 25 | 88.0 | [68.8–97.5] | 68.0 | [46.5–85.1] | 44.4 | [22.7–86.7] |

| 17 | 24 | 87.5 | [67.6–97.3] | 66.7 | [44.7–84.4] | 37.8 | [18.8–76.0] |

| 18 | 22 | 90.9 | [70.8–98.9] | 68.2 | [45.1–86.1] | 35.2 | [18.9–65.7] |

| 19 | 22 | 86.4 | [65.1–97.1] | 63.6 | [40.7–82.8] | 29.7 | [14.8–59.5] |

| 20 | 25 | 92.0 | [74.0–99.0] | 64.0 | [42.5–82.0] | 20.4 | [12.1–34.2] |

N, number of subjects with available results; S+, seropositivity defined as anti-HBs antibody concentrations ≥1.0 mIU/ml up to year 12 and ≥3.3 mIU/ml from year 13 onwards; GMC, geometric mean concentrations calculated on seropositive subjects; %, number/percentage of seropositive subjects or subjects with anti-HBs antibody concentrations ≥10 mIU/ml; 95% CI, exact 95% confidence interval; LL, lower limit of 95% confidence interval; UL, upper limit of 95% confidence interval; post-primary, anti-HBs antibody seroprotection rates and GMCs at Month 13, following primary vaccination at months 0, 1, 2 and 12.

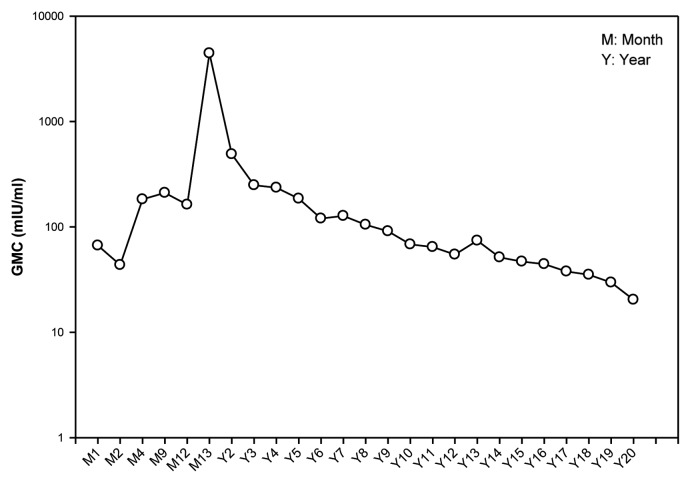

Anti-HBs antibody geometric mean concentration (GMC) (calculated on seropositive subjects) was 20.4 mIU/ml (95% CI: 12.1–34.2) (Table 1). The evolution of the anti-HBs antibody GMCs is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. GMC evolution of anti-HBs antibodies from Month 1 to year 20 post-dose-1 in the unboosted group (LT-ATP cohort for immunogenicity).

Immune response to the HBV vaccine challenge dose at year 20

Of the 29 subjects included in the ATP cohort of immunogenicity, three subjects had no detectable antibodies (<3.3 mIU/ml) before the administration of challenge dose. However, one month post-challenge dose, all subjects were found to be seropositive for anti-HBs antibodies. Among these subjects, an anamnestic response was observed in almost all subjects (n = 28/29; 96.6% (95% CI: 82.2–99.9) and 93.1% (95% CI: 77.2–99.2) had anti-HBs concentration ≥100 mIU/ml.

Overall, the anti-HBs antibody GMCs increased by 82-fold (13.2 to 1082.4 mIU/ml) in subjects from the pre- to post-challenge time-point.

Assessment of hepatitis markers

One subject, who acquired HBV infection at birth, did not respond to the primary vaccination course and maintained a chronic state throughout the long-term follow-up period. None of the other subjects reported clinical symptoms of HBV infection during the 20-y follow-up. Over the 20-y follow-up period, ten subjects were identified with probable sub-clinical HBV breakthrough infection, and false-positive results were observed in eight subjects.

Safety

No unsolicited adverse events were reported within the 31-d follow-up period post-challenge dose at year 20. No serious adverse events (SAEs) and pregnancies were reported during the challenge-phase of the study (NCT00657657).

Discussion

The present study consisted of a homogeneous cohort of infants born to mothers who were positive for HBsAg and HBeAg antigens. Although, results of vaccinating infants born to HBsAg/HBeAg positive mothers with hepatitis B vaccine have been published previously,9 the present study also focused on subjects who received a birth dose of hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIg) concomitantly with four doses of hepatitis B vaccine, with no booster dose. This study on high-risk infants demonstrated that anti-HBs antibodies persisted for at least up to 20 y following primary vaccination. Although a previously conducted study in Thailand demonstrated that a 3-dose schedule of HBV vaccine is sufficient to elicit immune memory for long-term protection, a fourth dose will increase the magnitude of immune response, with higher GMCs at year 20. At year 20, 92% of subjects had anti-HBs antibody concentration ≥3.3 mIU/ml and 64% of subjects had antibody ≥10 mIU/ml with a GMC of 20.4 mIU/ml.

The long-term persistence data are in agreement with previous studies conducted in Thailand8,9,11-14 and elsewhere15,16 in children less than 5 y of age. Vaccination-induced HBV immunity persists from infancy for at least 20 y following vaccination.8,9,11

It has been reported that infants vaccinated at birth and followed for approximately 20 y report lower rates of persistence.16 However, the results of the present study report higher proportion of subjects who are seropositive at year 20, as compared with these previous studies. A recent meta-analysis indicated that the protection offered by hepatitis B vaccines was influenced by the schedule of vaccine administration, vaccine dosage and the characteristics of the population.17 The main reason for the observed higher seropositivity in this study may be due to the 4-dose schedule. It has been shown previously that 4 doses of HBV vaccine have higher immunogenicity persistence compared with 3 doses of the same vaccine.8 In addition, the administration of HBIg at birth had no influence on the long-term persistence of antibodies, protecting infants in the first few months of life, when protection from vaccine is not fully established. Indeed, HBIg rapidly declines in the blood stream and does not impact later on in life, consequently does not contribute to the long-term persistence of the antibodies.9

The effectiveness of hepatitis B vaccination in preventing chronic infections, years after primary vaccination, has been demonstrated in other studies.18,19 Although the declining of circulating antibody levels might be interpreted as waning of protection conferred by the hepatitis B vaccine, an anamnestic response to HBV vaccine challenge dose, as observed in the present study, indicated the persistence of immune memory.20,21 The specific immunity to HBsAg outlasts the presence of vaccine-induced antibodies.22 In the current scenario, neither measurement of anti-HBs concentrations nor booster dose(s) are recommended for individuals who received the hepatitis B vaccine primary series during infancy.23

Primary vaccination also induced strong immune memory as evidenced by the anamnestic response to the year 20 challenge dose observed in all (96.6%) except one subject (originally a low responder). These results are in line with the previous study on similar population.8,9

As observed in previous studies in infants in Thailand, none of the subjects in this study reported clinical symptoms of HBV infection during the 20-y follow-up period.9,11 Among the ten subjects with possible sub clinical breakthrough HBV infection, five subjects seroconverted for antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) antibodies, and the remaining five subjects were HBV (HBsAg or HBV DNA or HBeAg) positive. Previous studies conducted in Alaska (3 doses and 16-y follow-up)24 and Gambia (3 doses and 15-y follow-up)25 report 1.8% and 10.1% of subjects positive for anti-HBc, respectively. In addition, 0.9% and 0.7% were positive for HBV DNA and HBsAg, respectively.24,25 The present study demonstrated that Thai children are at high risk of exposure to HBV due to the HBV endemicity. However, review of results of individual subjects indicated that none of the subjects with subclinical breakthrough HBV infection had clinical symptoms of HBV disease.

Although this study demonstrates the immune memory 20 y following vaccination with HBV vaccine, the demographics and immune response of the subjects at year 20 were not compared with the original cohort and their immune response at month 7 or 12. Consequently, bias in reporting of responders is acknowledged as a limitation of this study. Another shortcoming of this study was the low sample size (n = 25) which limited the generalizability of the results. In addition, the factors associated with the persistence of immune response and memory such as gender, body mass index, age or other underlying chronic conditions have not been studied as the sample size was not powered to produce clinically significant results and this would require further investigations.

In conclusion, this 20-y follow-up study has demonstrated the persistence of anti-HBs antibodies and immune memory for two decades following four-dose vaccination schedule. Given the high risk (70% to 90%) of chronic infection in Thai children due to the carrier state of their mothers,11 administration of hepatitis B vaccine may help in mitigating the risk of infection.

Materials and Methods

Study design and subjects

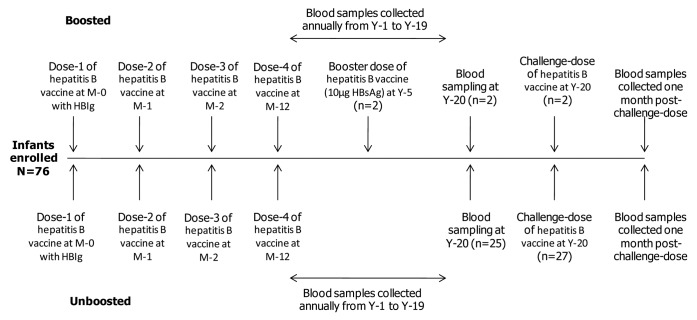

In an open primary study on hepatitis B vaccine conducted between June 1987 and May 1988 at Chulalongkorn University and Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand, healthy newborns received four doses of hepatitis B vaccine (10 μg recombinant HBsAg; Engerix-B™; GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines) intramuscularly in the deltoid or anterolateral thigh region. All infants received a single dose of HBIg concomitantly at the opposite arm or thigh at birth. The study design is illustrated in the Figure 2. The number of subjects who were boosted at year 5 and returned for blood sampling at this time point were low (n = 2). Therefore, this paper will not present the 20-y persistence data on these subjects as no comparative conclusions could be made.

Figure 2. Study design. This paper will not present the data on subjects boosted at Year-5 for long-term persistence since number of subjects in this group were low (n = 2), and these results do not provide any clinically relevant information. N, number of subjects in the LT-ATP cohort; N*, number of subjects in the ATP cohort for the challenge phase.

All subjects who participated in the primary vaccination study were invited to return for yearly blood sampling for 20 y to assess the long-term persistence of anti-HBs antibodies and other hepatitis markers (100449/NCT00240539). Subjects who had anti-HBs antibody concentrations <100 mIU/ml at the last available follow-up time-point (year 19 or before) were offered a HBV vaccine challenge dose at year 20 (110071/NCT00657657). The upper limit of 100 mIU/ml was chosen to eliminate subjects who may have received unreported additional vaccine doses or had demonstrated a natural booster response following exposure to HBV. Subjects were not offered the challenge dose if they had received investigational or non-registered medication or immunosuppressants during the conduct of the study or booster dose of hepatitis B vaccine outside the study context.

Written informed consent was obtained from each subject before conducting any study-related procedure. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University (Bangkok, Thailand), and was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice, the Declaration of Helsinki and local rules and regulations of Thailand.

Immunogenicity assessment

Blood samples were collected at yearly time-points up to year 20 to assess anti-HBs antibody concentrations and serological markers of hepatitis B infections (HBsAg, anti-HBs antibodies and anti-HBc antibodies) and at one month post-challenge time-point to assess the immune memory in the form of an anamnestic response. From the commencement of primary vaccination until year 12 follow-up, anti-HBs antibodies were measured using a radioimmunoassay (RIA) (AUSAB RIA, Abbott Laboratories) with an assay cut-off of 1.0 mIU/ml. From year 13 until year 17, antibodies were measured using Enzyme-linked Immunoassay (EIA) (AUSAB EIA, Abbott Laboratories). Samples collected from year 18 until year 20 were tested using an in-house validated EIA. The cut-off for the commercial and in-house EIA was 3.3mIU/ml.

Assessment of hepatitis markers

Anti-HBc antibody concentrations were measured using a RIA method until year 12 (Corab, Abbott Laboratories) and an EIA from year 13 onwards (AxSYM CORE/HBe, Abbott Laboratories). Anti-HBe antibody concentrations were measured using a microparticle Enzyme Immuno Assay (MEIA) from year 16 onwards (AxSYM, Abbott Laboratories). HBsAg concentration was determined using a RIA method until year 12 (AusRIA, Abbott Laboratories) and an EIA method (AxSYM/HBsAg, Abbott Laboratories) from year 13 onwards. The presence of HBV DNA was detected using in-house validated Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and Cobas® Monitor methodologies26 at Centre for Vaccinology, Ghent University and Hospital laboratories.

False positive was defined as single marker of HBV infection (HBsAg, HBeAg and anti-HBc), positive in one sample and negative for all other markers in the same sample and other HBV markers negative at consecutive time-points. Subclinical breakthrough HBV infection was defined as one or more HBV markers positive in one or more consecutive samples, excluding conditions for chronic HBV infection and false-positive result, without any reported clinical symptoms of hepatitis. New HBV infections were defined as detection of two or more positive markers in the same sample with no other positive markers at consecutive time-points. Chronic infections were defined as HBsAg positive and anti-HBc positive at more than two consecutive time-points.

Safety assessment

Safety assessment of the challenge dose at year 20 included reporting of unsolicited adverse events within 30 d following vaccination, and pregnancies and SAEs during the entire study period.

Statistical analyses

The GMC calculation for immunogenicity analyses was performed by taking the anti-log of the mean of the log antibody transformations.

The long-term follow-up phase included infants vaccinated with hepatitis B vaccine and who concomitantly received HBIg at first dose stage up to collection of blood samples at year 20. The challenge phase included collection of blood samples prior to and 1-mo post-challenge dose administration.

The LT-ATP cohort for immunogenicity included subjects who were a part of the ATP cohort for immunogenicity during the primary study at year 1, had serology results for year 20 blood-sampling time-point, had normal serology evolution and were compliant with vaccination and blood-sampling schedules and did not receive any vaccination other than study vaccine.

ATP cohort for immunogenicity for the challenge phase at year 20 included all subjects from year 1, who met all eligibility criteria, complied with the study procedures, did not dropout during the study, had data concerning immunogenicity endpoint measured at post-challenge time-point and had anti-HBs concentration <100 mIU/ml prior to the challenge dose.

For the long-term follow-up study, at year 20, the percentage of subjects with anti-HBs antibody concentrations ≥3.3 mIU/ml, ≥10 mIU/ml and anti-HBs geometric mean concentrations (GMCs) at each time-point were tabulated with 95% CI. The analysis was performed on the LT-ATP cohort for immunogenicity.

For the challenge phase, the percentage of subjects with anti-HBs antibody concentrations ≥ 3.3 mIU/ml, ≥ 10 mIU/ml, ≥ 100 mIU/ml and anti-HBs GMCs were evaluated with 95% CI. The analysis was performed on the ATP cohort for immunogenicity.

The percentage of subjects with an anamnestic response to hepatitis B vaccine challenge dose was evaluated with 95% CI. Anamnestic response was defined as anti-HBs antibody concentration ≥10 mIU/ml one month post-challenge dose as compared with pre-challenge anti-HBs concentration for seronegative subjects (subjects with anti-HBs concentration <3.3 mIU/ml), and at least a 4-fold increase in anti-HBs concentration post-challenge dose as compared with pre-challenge anti-HBs concentration for seropositive subjects (subjects with anti-HBs concentration ≥3.3 mIU/ml).

Safety analysis was performed on the total vaccinated cohort (TVC). The TVC included subjects who received hepatitis B challenge dose.

Trademark statement

Engerix-B is a registered trade mark of the GlaxoSmithKline group of companies.

Acknowledgments

We thank the infants and their families for participating in this trial. We also thank all investigators, the study nurses and other staff members of the Center of Excellence in Clinical Virology for contributing in many ways to this study. The authors thank Harshith Bhat for medical writing; Manjula K. and Lakshmi Hariharan for editorial and coordinating support in preparing this manuscript (all employees of the GlaxoSmithKline group of companies).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- Anti-HBc

antibody to hepatitis B core antigen

- Anti-HBe

antibody to hepatitis B e-antigen

- Anti-HBs

antibody to the hepatitis B surface antigen

- ATP

according-to-protocol

- CI

confidence interval

- EIA

enzyme immunoassay

- GMC

geometric mean concentration

- HBIg

hepatitis B immunoglobulin

- HBeAg

hepatitis B e-antigen

- HBsAg

hepatitis B surface antigen

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- LL

lower limit of 95% confidence interval

- LT-ATP

long term according-to-protocol

- MEIA

microparticle enzyme immuno assay

- mIU

milli-international units

- ml

milli liter

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RIA

radioimmunoassay

- SAE

serious adverse event

- TVC

total vaccinated cohort

- UL

upper limit of 95% confidence interval

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

Y.P. has received grants from the Thailand Research Fund (DPG5480002), the CU Centenary Academic Development Project and the National Research University Project of Thailand (HR1155A-55) for conducting research and clinical trials. Outside the scope of the submitted work, Y.P. also has received payments from the GlaxoSmithKline group of companies or other pharmaceutical companies for presenting lectures. V.C. and A.T. declare no conflicts of interest; P.C. is employed at GlaxoSmithKline group of companies; M.M. was employed by the GlaxoSmithKline group of companies as a consultant (from the CRO CHILTERN) at the time of this trial; K.H. is employed by the GlaxoSmithKline group of companies and also has stock ownership at the GlaxoSmithKline group of companies.

This study was sponsored and funded by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA. The sponsor was involved in all stages of the study, i.e,. from study design to data analysis and writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. Authors (Y.P. and A.T.) were supported by the Center of Excellence in Clinical Virology, Chulalongkorn University (CU56-HR01) the Thailand Research Fund (DPG5480002) and the National Research University Fund (HR1155A).

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/vaccines/article/24844

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Hepatitis B Vaccines. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2009; 84:405-20. Available at: http://www.who.int/wer. Last accessed 26 February 2013.

- 2.Heron L, Selnikova O, Moiseieva A, Van Damme P, van der Wielen M, Levie K, et al. Immunogenicity, reactogenicity and safety of two-dose versus three-dose (standard care) hepatitis B immunisation of healthy adolescents aged 11-15 years: a randomised controlled trial. Vaccine. 2007;25:2817–22. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Global progress toward universal childhood hepatitis B vaccination, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:868–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ni YH, Chang MH, Huang LM, Chen HL, Hsu HY, Chiu TY, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection in children and adolescents in a hyperendemic area: 15 years after mass hepatitis B vaccination. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:796–800. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang MH, Chen CJ, Lai MS, Hsu HM, Wu TC, Kong MS, et al. Taiwan Childhood Hepatoma Study Group Universal hepatitis B vaccination in Taiwan and the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in children. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1855–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706263362602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chongsrisawat V, Yoocharoen P, Theamboonlers A, Tharmaphornpilas P, Warinsathien P, Sinlaparatsamee S, et al. Hepatitis B seroprevalence in Thailand: 12 years after hepatitis B vaccine integration into the national expanded programme on immunization. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:1496–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.FitzSimons D, François G, Emiroğlu N, Van Damme P. Combined hepatitis B vaccines. Vaccine. 2003;21:1310–6. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00636-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poovorawan Y, Chongsrisawat V, Theamboonlers A, Bock HL, Leyssen M, Jacquet JM. Persistence of antibodies and immune memory to hepatitis B vaccine 20 years after infant vaccination in Thailand. Vaccine. 2010;28:730–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poovorawan Y, Chongsrisawat V, Theamboonlers A, Leroux-Roels G, Crasta PD, Hardt K. Persistence and immune memory to hepatitis B vaccine 20 years after primary vaccination of Thai infants, born to HBsAg and HBeAg positive mothers. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012;8:896–904. doi: 10.4161/hv.19989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sa-Nguanmoo P, Tangkijvanich P, Tharmaphornpilas P, Rasdjarmrearnsook AO, Plianpanich S, Thawornsuk N, et al. Molecular analysis of hepatitis B virus associated with vaccine failure in infants and mothers: a case-control study in Thailand. J Med Virol. 2012;84:1177–85. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poovorawan Y, Chongsrisawat V, Theamboonlers A, Leroux-Roels G, Kuriyakose S, Leyssen M, et al. Evidence of protection against clinical and chronic hepatitis B infection 20 years after infant vaccination in a high endemicity region. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:369–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01312.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poovorawan Y, Sanpavat S, Pongpunglert W, Chumdermpadetsuk S, Sentrakul P, Vandepapelière P, et al. Long term efficacy of hepatitis B vaccine in infants born to hepatitis B e antigen-positive mothers. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:816–21. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199210000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poovorawan Y, Sanpavat S, Chumdermpadetsuk S, Safary A. Long-term hepatitis B vaccine in infants born to hepatitis B e antigen positive mothers. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1997;77:F47–51. doi: 10.1136/fn.77.1.F47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chinchai T, Chirathaworn C, Praianantathavorn K, Theamboonlers A, Hutagalung Y, Bock PH, et al. Long-term humoral and cellular immune response to hepatitis B vaccine in high-risk children 18-20 years after neonatal immunization. Viral Immunol. 2009;22:125–30. doi: 10.1089/vim.2008.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bialek SR, Bower WA, Novak R, Helgenberger L, Auerbach SB, Williams IT, et al. Persistence of protection against hepatitis B virus infection among adolescents vaccinated with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine beginning at birth: a 15-year follow-up study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:881–5. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31817702ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammitt LL, Hennessy TW, Fiore AE, Zanis C, Hummel KB, Dunaway E, et al. Hepatitis B immunity in children vaccinated with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine beginning at birth: a follow-up study at 15 years. Vaccine. 2007;25:6958–64. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schönberger K, Riedel C, Rückinger S, Mansmann U, Jilg W, Kries RV. Determinants of Long Term Protection after Hepatitis B Vaccination in Infancy: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:307–13. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31827bd1b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu CY, Chiang BL, Chi WK, Chang MH, Ni YH, Hsu HM, et al. Waning immunity to plasma-derived hepatitis B vaccine and the need for boosters 15 years after neonatal vaccination. Hepatology. 2004;40:1415–20. doi: 10.1002/hep.20490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mele A, Tancredi F, Romanò L, Giuseppone A, Colucci M, Sangiuolo A, et al. Effectiveness of hepatitis B vaccination in babies born to hepatitis B surface antigen-positive mothers in Italy. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:905–8. doi: 10.1086/323396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banatvala JE, Van Damme P. Hepatitis B vaccine-do we need boosters? J Hepatol. 2003;10:1–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fitzsimons D, François G, Hall A, McMahon B, Meheus A, Zanetti A, et al. Long-term efficacy of hepatitis B vaccine, booster policy, and impact of hepatitis B virus mutants. Vaccine. 2005;23:4158–66. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Damme P, Ward J, Shouval D, Wiersma S, Zanetti A. Hepatitis B vaccines. In: Plotkin SA, ed. Vaccines. 6th ed. Doylestown, PA: Elsevier Saunders, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Academy of Pediatrics. Hepatitis B. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Long SS, McMillan JA, editors. Red Book: 2006 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 27th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2006:343-4. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dentinger CM, McMahon BJ, Butler JC, Dunaway CE, Zanis CL, Bulkow LR, et al. Persistence of antibody to hepatitis B and protection from disease among Alaska natives immunized at birth. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:786–92. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000176617.63457.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Sande MA, Waight P, Mendy M, Rayco-Solon P, Hutt P, Fulford T, et al. Long-term protection against carriage of hepatitis B virus after infant vaccination. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1528–35. doi: 10.1086/503433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noborg U, Gusdal A, Pisa EK, Hedrum A, Lindh M. Automated quantitative analysis of hepatitis B virus DNA by using the Cobas Amplicor HBV monitor test. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2793–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.9.2793-2797.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]