Abstract

In response, pediatric practices have adopted vaccine policies that require parents who refuse to vaccinate according to the ACIP schedule to find another health care provider. Such policies may inadvertently cluster unvaccinated patients into practices that tolerate non vaccination or alternative schedules, turning them into risky pockets of low herd immunity. The objective of this study was to assess the effect of provider zero-tolerance vaccination policies on the clustering of intentionally unvaccinated children. We developed an agent-based model of parental vaccine hesitancy, provider non-vaccination tolerance, and selection of patients into pediatric practices. We ran 84 experiments across a range of parental hesitancy and provider tolerance scenarios. When the model is initialized, all providers accommodate refusals and intentionally unvaccinated children are evenly distributed across providers. As provider tolerance decreases, hesitant children become more clustered in a smaller number of practices and eventually are not able to find a practice that will accept them. Each of these effects becomes more pronounced as the level of hesitancy in the population rises. Heterogeneity in practice tolerance to vaccine-hesitant parents has the unintended result of concentrating susceptible individuals within a small number of tolerant practices, while providing little if any compensatory protection to adherent individuals. These externalities suggest an agenda for stricter policy regulation of individual practice decisions.

Keywords: vaccination, immunization, immunization schedule, decision-making, parents

Introduction

Many parents are reluctant to allow their children to be vaccinated according to the ACIP vaccination schedule and such vaccine hesitancy has been increasing over time.1-4 Pediatric providers report frequent requests for alternative schedules and significant time required to counsel vaccine-hesitant parents during well-child visits.5-7 Many pediatric practices have adopted vaccine policies that require parents who refuse to vaccinate according to the ACIP schedule to find another health care provider.7,8 While such patient dismissals run counter to AAP guidelines and policy statements,9 clinicians have justified such policies by claiming a responsibility to protect other patients in the practice from the risk of unvaccinated children seated in a waiting room. Nationally-representative surveys of pediatric providers indicate that 29% would dismiss a family who refused some vaccines and 40% would dismiss a family who refused all vaccines.10

There is vigorous debate within the pediatrics community about the ethics of dismissal policies.9,11-13 On the one hand, pediatric providers want to take a firm stance against alternative schedules and outright refusal in order to protect their patients and prevent what is seen as a creep toward more vaccine hesitancy. Some argue that vaccine refusal may constitute medical neglect,9,11 and that accommodating refusal may leave the provider liable for outbreaks caused by intentional unvaccination.13 Others argue that dismissal policies are unnecessarily harsh, and may leave the children of hesitant parents without a regular source of care.13 This debate has neglected a critical aspect of these dismissal policies: the decisions one practice makes may affect the concentration of at-risk patients seen in nearby practices. Given recent evidence that the pediatric outpatient office can be an important site of exposure to vaccine-preventable diseases,14 the heterogeneity and distribution of practice vaccination policies within a community may contribute to the risk of disease outbreaks.

We use agent-based simulation to highlight the effects of patient dismissal policies on three outcomes: (1) the extent of clustering of vaccine-hesitant patients within practices, (2) the exposure of vaccinated patients to unvaccinated patients, and (3) the proportion of patients who are unable to find a pediatrician. Practices with a higher proportion of unvaccinated patients may become “hotspots” at higher risk of causing or sustaining an outbreak compared with practices where more patients are up-to-date on vaccines.

Results

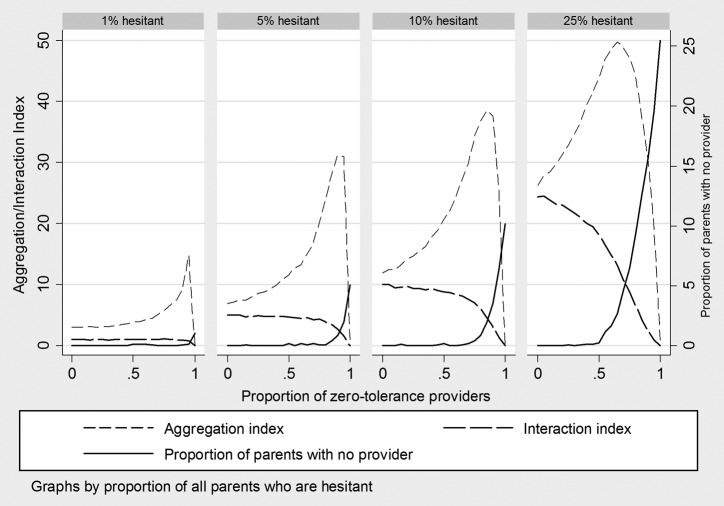

The results from 84 experiments described below are summarized in Figure 1. Each graph plots the end point of three outcome variables (interaction index, aggregation index, and proportion of parents with no provider) as the proportion of zero-tolerance providers increases, at a set level of parental hesitancy (moving from 1% in the left-most graph to 25% on the right).

Figure 1. Simulated effect of provider zero-tolerance policies on isolation of vaccine-hesitant patients within provider practices and exposure of adherent patients to hesitant patients.

Across the four hesitancy prevalence scenarios, results are qualitatively similar. Where there are no zero-tolerant providers, all parents are able to find a provider. The aggregation index (reflecting exposure of hesitants to each other) and the interaction index (reflecting exposure of adherents to hesitants) are close in value, with the aggregation index slightly above and the interaction index at or slightly below the overall proportion hesitant in the population.

As the proportion of zero-tolerant practices increases at a given level of parental hesitancy (moving from left to right within each graph in Figure 1), two phenomena can be observed. First, the aggregation index rises gradually, has a dramatic spike, and then drops to zero when the proportion of zero-tolerant providers reaches 100%. The aggregation index drops to zero when zero tolerance equals 100% because all hesitant parents have been dismissed from practices, and therefore there is no practice-level exposure of hesitants to hesitants. This dismissal can be seen in the rising proportion of parents with no provider, measured on the right-hand scale of each graph, which approaches the proportion of hesitant parents as the proportion of zero-tolerant providers approaches 100%. As provider tolerance approaches zero, hesitant parents will be increasingly clustered in the small number of remaining tolerant practices, and hesitant parents will find it increasingly difficult to get any care for their children.

The second observable result of the simulation model is the declining interaction index that accompanies the rising aggregation index. As hesitants are clustered within tolerant practices, the average adherent actually sees fewer hesitants in the remaining practices. As was the case for the aggregation index, the interaction index drops to zero when all providers are zero-tolerant because there are no hesitant parents remaining in the practices and therefore no exposure to them.

The four graphs reveal the impact of changing levels of provider tolerance under different proportions of vaccine hesitancy. At 1% hesitancy prevalence, provider tolerance has minimal impact on aggregation and isolation until it reaches about 70% zero-tolerant. Even at 90%, the aggregation index remains below 20 and all parents are able to find a provider. However, documented parental hesitancy is considerably higher than 1%.2 At 5–10% hesitancy (the middle two graphs), which more closely reflect real rates of hesitancy among parents of young children, the system can still accommodate a substantial proportion of zero-tolerant providers. However, aggregation spikes to 30–40, meaning that hesitant parents are in practices where the average percent hesitant is 30–40, and hesitant parents end up without a provider at lower levels of provider zero tolerance.

At 50% zero-tolerance, the aggregation index peaks at 50. The interaction index at this point is 20, meaning that exposure to hesitants for adherents has not dropped that far below the population-level prevalence of hesitancy. The proportion of patients with no provider also increases rapidly as zero tolerance exceeds 50%.

Discussion

This study uses a simple agent-based simulation model to examine the effects of provider dismissal policies on the clustering of unvaccinated children within pediatric practices under different conditions of parental vaccine hesitancy. Our results build on other agent-based and game theoretic models of infectious disease dynamics that incorporate social and behavioral aspects of vaccine preferences and behaviors.15-22 The model highlights three implications of provider tolerance policies: First, when all providers accommodate refusals and do not dismiss hesitant parents, intentionally unvaccinated children are more evenly distributed across providers such that the exposure of hesitant and adherent parents to hesitant parents in the pediatric outpatient setting is close to the population-level hesitancy prevalence. As the number of providers tolerant of hesitant parents decreases, however, hesitant children become increasingly clustered in a smaller number of practices and, at the upper limit of zero-tolerance, the hesitant parents are unable to find a practice that will accept their children. Second, adherent patients are less likely to encounter hesitant patients as provider tolerance decreases. From the provider perspective, this may be considered a desirable outcome, particularly because it reduces the exposure of infants of adherent parents who are too young to be vaccinated to unvaccinated children. However, the positive effects for adherent patients are modest, as evidenced in our model by the minimal drop in exposure to hesitants as zero-tolerance increases. At the same time, the negative effects for hesitant patients of rapid increases in exposure to other hesitants, and potential difficulties in accessing care, are proportionately greater. This asymmetry is an important intuition from the model: while providers often claim that zero-tolerance is an important policy to limit the exposure of their patients to unvaccinated children, at the population level this effect may be dwarfed by the increased risk of exposure for unvaccinated children clustered in a smaller number of tolerant practices, at least at this level of hesitancy. Third, both of these effects become more pronounced as the level of hesitancy in the population rises.

These results reveal that the policies of individual pediatric practices produce health effects extending beyond their practice and into their local communities. They also reveal that it is the heterogeneity of practice policies that creates the greatest concentration of hesitant parents, potential hotspots for outbreaks.

These results reveal inherent compromises when recommending practice-level policies. To minimize clustering and ensure that all children have a provider, it is better to have no zero-tolerance providers. However, such permissive policies send a message that conflicts with the importance and value of vaccination. In contrast, if no provider will accept a vaccine-hesitant parent, office-based exposure of adherents is zero, a strong message is sent, some parents are forced to adhere to the recommended vaccine schedule, and some children go without care. Between these two extremes, heterogeneity in tolerance and dismissal policies will cluster unvaccinated children in a smaller number of practices, which may differentially increase the risk of exposure for some children. As professional associations and individual practices debate policies for accommodating vs. dismissing families who choose not to vaccinate, our results highlight important implications for population-level patterns of disease risk that emerge from practice-level decisions. Our results for pediatric practices are consistent with previous work demonstrating the disease risks associated with significant heterogeneity in school-level rates of intentional undervaccination.4,23 While it can be appealing to allow individual practices or schools to set their own rules for accommodating vaccine hesitancy, differences in tolerance can result in spatial and social concentration of risks. Modeling this concentration can reveal the potential public health cost of otherwise well-meaning policies related to vaccine hesitancy and accommodation.

Our study has important limitations. Our model is a vast simplification of the dynamic processes by which parents choose pediatric providers and providers implement vaccine policies based on their tolerance of vaccine hesitancy. More complex models might reflect additional agent characteristics and decision or feedback processes, including parental preferences for providers that are unrelated to vaccine hesitance (i.e., provider popularity), provider ability to persuade parents to adopt the recommended schedule; threshold responses to parental hesitancy that trigger dismissal; and exposures of hesitant and adherents to other hesitants in settings outside of provider offices. More complex models might also introduce stochastic disease outbreaks and map contagion across vaccinated and unvaccinated patients, across practices, and across a community. It is also important to note that vaccine hesitancy is a socially and spatially clustered behavior, and this clustering likely shapes exposure risk in community or school settings in addition to the outpatient setting modeled here. However, the simple structure of our model is also an advantage, as it allows us to isolate and communicate the specific effect of zero-tolerance policies on the distribution of intentionally unvaccinated children in the population. The stylized results of this model are not meant to identify an optimal policy point, but to reveal the population-level effects of individual practice decisions.

Conclusion

Results from a simple agent-based model suggest that while it can seem appealing to allow practices to set their own tolerance for vaccine hesitancy, heterogeneity in those policies has the unintended result of concentrating susceptible individuals within a small number of tolerant practices, while providing little if any compensatory protection to adherent individuals. With communicable diseases, the externalities, or risks to others, created by non-vaccinators are well-known: they increase the risk of exposure for other individuals who were not able to choose to incur that risk. Those externalities underlie efforts to promote full vaccination in support of herd immunity. The results of this model reveal that externalities are generated not just by hesitant parents, but also by practice policies that end up concentrating the children of those hesitant parents. Practices that dismiss hesitant patients increase risks at other practices, because they produce higher concentrations of unvaccinated children in those practices. Our simplified model suggests that the reduction in risk in dismissing practices is likely smaller than the increase in risk in more tolerant practices, and therefore that the net effect on population-level risk is undesirable.

Materials and Methods

Agent-based model of vaccine refusal and provider tolerance

The distribution of vaccine hesitancy and refusal across pediatric practices is determined by complex characteristics and preferences of both parents and providers that are difficult to capture in standard linear regression models. Agent-Based Models (ABMs) are a subset of computational modeling that takes a “bottom-up” approach to understanding complex systems dynamics. ABMs use stylized assumptions to create a population of simulated agents that interact according to a distinct set of conditions, mechanisms, and behavioral rules to reveal macro level population effects.24 These models allow us to move beyond overly-simplified linear approaches and observe how interdependent, individual behaviors can generate the complex aggregate vaccine hesitancy patterns that contribute to disease outbreak risk.

ABMs are particularly good at reflecting the reality of hetereogeneity within a population by assuming that each agent has its own behavioral attributes, and makes decisions based on these characteristics while also adapting to feedback from other agents. Models step through cycles that can reflect effects and events across discrete time. ABMs have been previously applied to infectious disease modeling22,25,26 as well as to other health issues with complex social, spatial, behavioral, and temporal elements.27-33

In the case of vaccine refusal, different combinations of individual preferences for vaccination and feedback processes between parents and their pediatric providers create a diverse and complex environment. A parent can be described by his or her willingness to vaccinate a child under the ACIP schedule, ability to identify practices with concordant policies, or willingness to travel long distances to pediatric practices—each of which determines where that parent seeks pediatric care. A pediatric practice can be described by its tolerance of alternative schedules. With limited options, some parents may choose to remain vaccine-hesitant and forgo pediatric care until they find a more flexible provider. Our simple ABM explores the implications of individual pediatric provider tolerance for parental vaccine refusal and its effects on population level parental vaccine hesitancy. This study did not involve human subjects.

Model description

Agent types and agent-level variables

Our model includes two agent types: parents and providers. Parents are characterized by their vaccine hesitancy, defined as a binary (true/false) variable. If the proportion of hesitant parents in the population is set (by the analyst) at 5%, then each parent has a 5% chance of being assigned the attribute of hesitant. Parents are also characterized by age, a value from 0 to 6 that reflects their time in the model as measured by time-steps (ticks), and proxies the age of the parent’s child. Parents therefore enter, age through, and leave provider practices.

Providers are characterized by their practice size capacities and their tolerance for hesitant parents. Practice size capacity (total number of parents assigned) for each provider is pulled at random from a triangular distribution between 25 and 100 parents, with mode at 50 parents. Provider tolerance is a binary variable, with tolerant providers willing to accept all patients, including vaccine-hesitant parents, and zero-tolerant providers accepting only non-hesitant parents. The proportion of hesitant providers in the population of providers is set by the analyst. Parents are initially randomly assigned to providers, regardless of provider tolerance and practice size capacity.

Parent decision mechanisms

At each time step of the model, parents age one additional year. Parents who have a provider remain with that provider until they reach age = 6; parents without a provider (and hesitant parents who are initially assigned to a zero-tolerant practice) search across all providers in random order each step until they find one that will accept them. It is possible for parents to age all six time steps without finding a provider. Each parent that leaves the model once age = 6 is replaced by the one new agent, initialized with age = 0, representing a newborn infant assigned with an initial hesitancy as previously described and no provider.

Provider decision mechanisms

At each time step, providers accept new parents if they have not reached their practice size capacity. The type of parent that each provider is willing to accept is determined by their tolerance (e.g., zero-tolerant providers never accept hesitant parents, and tolerant providers accept any parent).

Variable parameters and outcome measures

The model is initialized with five variable parameters: (1) number of providers, (2) number of patients, (3) proportion of parents that are hesitant, (4) proportion of providers that are zero-tolerant, and (5) distribution of provider size capacities. By changing these variables, we are able to understand how different combinations of parent and provider characteristics impact the distribution of hesitant parents within practices, and where critical values or nonlinearities may emerge.

The model tracks three outcomes of clinical and policy relevance. The first is the aggregation index, or the average practice-level hesitancy prevalence as observed by the subgroup of hesitant parents (hereafter, “hesitant”).4 The index measures the probability that a hesitant parent is in a pediatric practice with another hesitant, and is calculated as the proportion hesitant in each practice weighted by the practice’s proportion of all hesitants, summed across practices:

where xi is the number of hesitants in practice i, X is the total number hesitants, pi is the total number of patients in practice i, and N is the number of practices. The index runs from asymptotically near 0 to 100. As hesitants are less likely to vaccinate their children than are non-hesitant or adherent parents, the risk of disease exposure may be greater under conditions of high aggregation.

The second outcome is the exposure of vaccine adherent parents to hesitant parents, called the interaction index. The interaction index can be interpreted as the average practice-level proportion hesitant as observed by the subgroup of all non-hesitant or adherent parents (hereafter, “adherents”). The interaction index is calculated as the proportion hesitant in each practice weighted by the practice’s proportion of all adherents, summed across all practices:

where ai is the number of adherents in practice i, A is the total number adherents, xi is the number of hesitants in practice i, pi is the patient population in practice i, and N is the number of practices. The maximum value for the interaction index is the proportion of hesitants in the population. While adherents are for the most part vaccinated, some will be too young to be vaccinated and others may still be susceptible to disease even if vaccinated. The interaction index can therefore be considered a proxy for exposure risk in the adherent population.

The third outcome tracked by the model is the proportion of parents who are unable to find a provider. Parents may be unable to find a provider due to practice size constraints. One concern about dismissal or zero-tolerance policies is that children of vaccine hesitant-parents may not receive adequate care if parents are unable to find a practice willing to accommodate vaccine refusal or alternative vaccination schedules.

Experiments

In separate experiments, we varied the percentage of zero-tolerant providers from 0% to 100% in 21 5% increments (0%, 5%, 10%,…,100%) and for each of these we set the percent of hesitant parents in the population at 1%, 5%, 10%, and 25%. As an upper bound of hesitancy, 25% is higher than current estimates of the proportion of parents who request alternative schedules or decline vaccines altogether; however, it is in line with estimates of the number of parents who state they have concerns about vaccine safety.2 These parameters yielded 84 (21 X 4) experiments. We fixed the number of providers at 20 and the number of parents at 1000. Practice size cap distribution was held constant as described in the provider characteristics section above. We allowed each model to run for 200 ticks to reach equilibrium. We repeated each experiment 50 times, with results averaged across the 50 runs for each of the 84 experiments.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health and Society Scholars Program at the University of Pennsylvania and by the National Cancer Institute (1KM1CA156715–01).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ABM

agent-based modeling

- ACIP

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/vaccines/article/25635

References

- 1.Smith PJ, Humiston SG, Parnell T, Vannice KS, Salmon DA. The association between intentional delay of vaccine administration and timely childhood vaccination coverage. Public Health Rep. 2010;125:534–41. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomson Reuters-NPR. Health Poll September 2011: Vaccines. New York: Thomson Reuters - NPR.

- 3.Robison SG, Groom H, Young C. Frequency of alternative immunization schedule use in a metropolitan area. Pediatrics. 2012;130:32–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buttenheim A, Jones M, Baras Y. Exposure to personal belief exemptions from mandated school entry vaccinations among California kindergarteners. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:e59–e67. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Healy CM, Pickering LK. How to communicate with vaccine-hesitant parents. Pediatrics. 2011;127(Suppl 1):S127–33. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1722S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kempe A, Daley MF, McCauley MM, Crane LA, Suh CA, Kennedy AM, et al. Prevalence of parental concerns about childhood vaccines: the experience of primary care physicians. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:548–55. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leib S, Liberatos P, Edwards K. Pediatricians’ experience with and response to parental vaccine safety concerns and vaccine refusals: a survey of Connecticut pediatricians. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(Suppl 2):13–23. doi: 10.1177/00333549111260S203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.All Star Pediatrics. Immunization and Screening Schedule.

- 9.Diekema DS, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics Responding to parental refusals of immunization of children. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1428–31. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flanagan-Klygis EA, Sharp LK, Frader JE. Dismissing the family who refuses vaccines: a study of pediatrician attitudes. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:929–34. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.10.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diekema DS. Choices Should Have Consequences: Failure to Vaccinate, Harm to Others, and Civil Liability. Mich Law Rev. 2009;107:90–4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nulty D. Is It Ethical for a Medical Practice to Dismiss a Family Based on Their Decision Not to Have Their Child Immunized? JONA's Healthcare Law. Ethics and Regulation. 2011;13:122–4. doi: 10.1097/NHL.0b013e31823a61e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halperin B, Melnychuk R, Downie J, Macdonald N. When is it permissible to dismiss a family who refuses vaccines? Legal, ethical and public health perspectives. Paediatr Child Health. 2007;12:843–5. doi: 10.1093/pch/12.10.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugerman DE, Barskey AE, Delea MG, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Bi D, Ralston KJ, et al. Measles outbreak in a highly vaccinated population, San Diego, 2008: role of the intentionally undervaccinated. Pediatrics. 2010;125:747–55. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Auld MC. Choices, beliefs, and infectious disease dynamics. J Health Econ. 2003;22:361–77. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(02)00103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shim E, Grefenstette JJ, Albert SM, Cakouros BE, Burke DS. A game dynamic model for vaccine skeptics and vaccine believers: measles as an example. J Theor Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2011.11.005. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coelho FC, Codeço CT. Dynamic modeling of vaccinating behavior as a function of individual beliefs. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.d’Onofrio A, Manfredi P, Salinelli E. Vaccinating behaviour, information, and the dynamics of SIR vaccine preventable diseases. Theor Popul Biol. 2007;71:301–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tpb.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salathé M, Bonhoeffer S. The effect of opinion clustering on disease outbreaks. J R Soc Interface. 2008;5:1505–8. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perisic A, Bauch CT. A simulation analysis to characterize the dynamics of vaccinating behaviour on contact networks. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perisic A, Bauch CT. Social contact networks and disease eradicability under voluntary vaccination. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrett CL, Bisset KR, Eubank SG, Feng X, Marathe MV. EpiSimdemics: an efficient algorithm for simulating the spread of infectious disease over large realistic social networks. Proceedings of the 2008 ACM/IEEE conference on Supercomputing. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE Press, 2008:37:1–:12. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith PJ, Chu SY, Barker LE. Children who have received no vaccines: who are they and where do they live? Pediatrics. 2004;114:187–95. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epstein JM, Axtell R. Growing artificial societies: social science from the bottom up. The MIT Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burke DS, Epstein JM, Cummings DAT, Parker JI, Cline KC, Singa RM, et al. Individual-based computational modeling of smallpox epidemic control strategies. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:1142–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2006.tb01638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eubank S, Guclu H, Kumar VS, Marathe MV, Srinivasan A, Toroczkai Z, et al. Modelling disease outbreaks in realistic urban social networks. Nature. 2004;429:180–4. doi: 10.1038/nature02541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Auchincloss AH, Diez Roux AV. A new tool for epidemiology: the usefulness of dynamic-agent models in understanding place effects on health. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:1–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gorman DM, Mezic J, Mezic I, Gruenewald PJ. Agent-based modeling of drinking behavior: a preliminary model and potential applications to theory and practice. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2055–60. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.063289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonabeau E. Agent-based modeling: methods and techniques for simulating human systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(Suppl 3):7280–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082080899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galea S, Hall C, Kaplan GA. Social epidemiology and complex system dynamic modelling as applied to health behaviour and drug use research. Int J Drug Policy. 2009;20:209–16. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galea S, Riddle M, Kaplan GA. Causal thinking and complex system approaches in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:97–106. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Auchincloss AH, Riolo RL, Brown DG, Cook J, Diez Roux AV. An agent-based model of income inequalities in diet in the context of residential segregation. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:303–11. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diez Roux AV, Auchincloss AH. Understanding the social determinants of behaviours: can new methods help? Int J Drug Policy. 2009;20:227–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]