Abstract

Influenza and pertussis prevention in young infants requires immunizing pregnant women and all caregivers (cocooning). We evaluated the knowledge and attitude of postpartum women about these two recommendations. A survey of predominantly Hispanic, underinsured, medically underserved postpartum women in Houston, Texas was performed during June 2010 through July 2012. Five hundred eleven postpartum women [mean age 28.8 y (18–45); 94% Hispanic] with a mean of 3 children (1–12) participated. Ninety-one (17.8%) were first-time mothers. Four hundred ninety-six (97.1%) received prenatal care; care was delayed in 24.3%. Only 313 (61.3%) received vaccine education while pregnant, and 291 (57%) were immunized. Four hundred seventy-four women (93%) were willing to be immunized during pregnancy if recommended by their healthcare provider, (the most trusted information source for 62%). Immunization of infants or infant caregivers had been discussed with 41% and 10% of mothers, respectively. Two hundred thirty women (45%) had received influenza vaccine; most intended to (79%) or had already received (15%) tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine. Preferred locations for cocooning were hospital or community clinics (97%). Insufficient knowledge (46.6%), cost (31.4%), lack of transportation (26%), work commitments (13.3%), and fear of needles (13.3%) were perceived barriers to cocooning. Level of formal education received by mothers had no effect on the quantity or quality of immunization education received during PNC or their attitude toward immunization. Immunization during pregnancy and cocooning, if recommended by providers, are acceptable in this high-risk population. Healthcare providers, as reported in infant studies, have the greatest influence on vaccine acceptance by pregnant and postpartum women.

Keywords: maternal immunization, cocooning, pregnancy, influenza, pertussis, attitudes, provider

Introduction

The unacceptably high incidence of some vaccine-preventable diseases in mothers and young infants in the United States, despite achieving record infant and childhood vaccination coverage, has focused attention on developing effective prevention strategies. Influenza was established as a significant mortality risk for pregnant women during the 1918 and 1957 pandemics.1 During the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, pregnant women had a 7-fold higher hospitalization rate than their non-pregnant counterparts and accounted for 6% of all influenza-related deaths while representing only 1% of the population.2 However, young infants also are particularly susceptible to morbidity and mortality from vaccine-preventable diseases such as influenza and pertussis. Vaccines are either not available for infants less than six months of age (i.e., influenza) or multiple doses are required to achieve protection (i.e., pertussis).3-7 These young infants have more influenza-related hospitalizations and deaths than other children,3,4 and those who have not completed their primary vaccination series have 20-fold higher incidence rates of pertussis than the general population. Two-thirds of pertussis infected babies are hospitalized and mortality occurs almost exclusively in this age group.5-9

Immunization strategies selected to reduce vaccine-preventable diseases in mothers and young infants include immunization during pregnancy and immunizing all infant caregivers or “cocooning.” The benefits to the infant of maternal immunization are both direct through passive transfer of maternal antibody and indirect by preventing transmission of disease via an infected mother.1,10,11 Both strategies are recommended to prevent infant influenza and pertussis.12-15 Healthcare providers (HCP) have achieved excellent vaccination coverage among children. Unfortunately, vaccination coverage among adults has lagged far behind.16 Pregnant women are a particular immunization challenge, at least in part due to reticence of both healthcare providers and pregnant women.17,18 Although recommended since 1997 in the United States (US), many HCPs do not routinely offer influenza vaccine during pregnancy or counsel women on its use.19,20 Despite the over-representation of pregnant women in morbidity and mortality rates during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, vaccination coverage with influenza vaccine was only 50% in pregnant women during the 2010–2011 influenza season.21 Routine administration of pertussis vaccine during pregnancy was first recommended in the US in 2011,22 but it is estimated that less than 5% of pregnant women have received combined tetanus, diphtheria and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine. In addition, although cocooning has been recommended to prevent pertussis since 2006, logistical and financial barriers have limited widespread implementation apart from a few individual programs.23-27 Immunization during pregnancy and cocooning are targeted strategies that will form the foundation for perinatal prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases during the next decade. However, there are few data on knowledge and acceptability of either strategy among new mothers.

Ben Taub General Hospital (BTGH) is a part of the tax-supported Harris Health System, and is one of two major public hospitals for greater metropolitan Houston, Texas. Approximately 4000 live-born infants, predominantly of Hispanic ethnicity (>90%), are delivered annually. BTGH serves a largely underinsured, medically underserved, predominantly Spanish-speaking population. Since 2008, a pertussis cocooning program at BTGH has offered Tdap vaccine to postpartum women and more recently to contacts of newborn infants who have not previously been immunized.23 We surveyed postpartum women in BTGH to determine their knowledge of current immunization recommendations and their perceived barriers to implementation

Results

Study population

Five hundred and 11 postpartum women (mean age 28.8 y; range 18 to 45 y) completed the survey between June 2010 and July 2012. Participant characteristics are described in Table 1. The majority of women (94%) were Hispanic and were uninsured (63%) or covered only by county-provided fee-for-service safety net plans (18.6%). Four hundred and 20 (82.3%) had more than one child.

Table 1. Characteristics of Postpartum Women.

| Age group | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| < 20 y | 33 | 6.4 |

| 20–29 y | 240 | 47.0 |

| 30–39 y | 215 | 42.1 |

| 40 + years | 23 | 4.5 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 481 | 94.1 |

| Black | 23 | 4.5 |

| White | 5 | 1 |

| Other | 1 | 0.2 |

| Number of living children | ||

| 1 | 91 | 17.8 |

| 2–3 | 284 | 55.5 |

| ≥ 4 | 136 | 26.6 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 99 | 19.5 |

| Married or partner | 411 | 80.5 |

| Years of formal education | ||

| 1–6 | 151 | 29.5 |

| 7–9 | 149 | 29.4 |

| 10–13 | 184 | 36 |

| ≥14 | 27 | 5.4 |

| Medical benefits | ||

| None | 324 | 63.4% |

| Medicaid | 30 | 5.9% |

| Gold Card * | 95 | 18.6% |

| Private | 1 | 0.2% |

| Other | 61 | 11.9% |

| Prenatal care provider | ||

| Family practitioner | 28 | 5.6% |

| Midwife | 170 | 34.3% |

| Obstetrician | 213 | 42.9% |

| Unknown or none | 100 | 17.1% |

*Texas public health benefit that provides subsidized medical costs.

Four hundred and 96 women (97.1%) received prenatal care (PNC), although PNC was delayed (began after the first trimester) in 124 (24.3%). PNC was most often provided by physicians (obstetricians or family practitioners); more than one-third of women received care from a midwife.

Information Sources

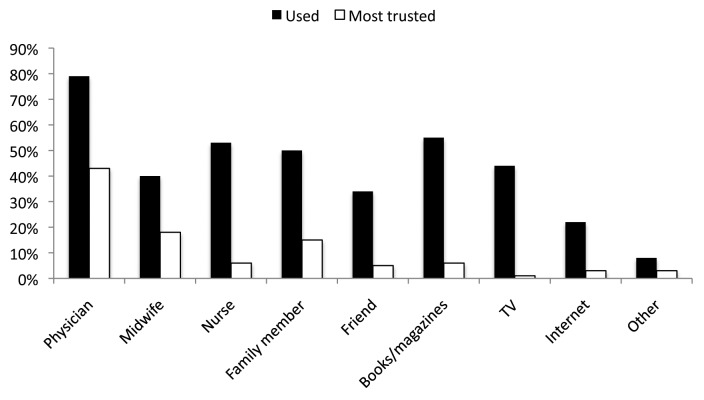

Women utilized a wide variety of sources to obtain health information during their pregnancy (Fig. 1). Three hundred 36 women (65.7%) considered a healthcare provider—physician, midwife, or nurse—their single most important and trusted source of information during their pregnancy.

Figure 1. Sources of information about pregnancy used and most trusted by women.

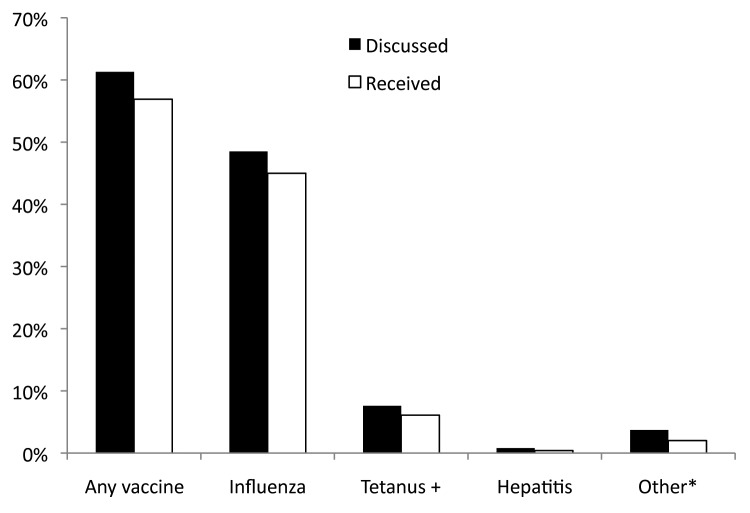

Education about Immunizations

Three hundred and 13 women (61.3%) acknowledged receiving education about immunizations while pregnant. The majority of this group (291 [93%]) who were advised that specific immunizations were recommended for them during pregnancy were subsequently immunized (Fig. 2). All surveyed women were pregnant at some time during influenza season, but only 49% had discussed influenza vaccine with their HCP and only 46% were immunized. Seven of 137 women (5%) who completed the survey after the 2011 recommendation to give Tdap during pregnancy was made, had this option discussed with them; six of these received the vaccine. Maternal knowledge of pregnancy immunization recommendations was not related to parity, years of formal education, ethnicity or insurance status, but women whose PNC was delivered by a midwife rather than a physician were more likely to have discussed immunization during pregnancy with their provider (72% vs. 58%; p = 0.015). This association remained significant after controlling for other demographic factors by logistic regression analysis (p = 0.002).

Figure 2. Percentage of women with whom vaccines were discussed and who received vaccines during prenatal care. + Tetanus toxoid (TT) or Tetanus, diphtheria toxoids (Td). *Includes Tdap. The recommendation to administer Tdap in pregnancy was made later in the study period.

Two hundred and eight women (41%) reported a PNC conversation with a HCP about the importance of immunizing their infant and 51 (10%) about the value of immunizing family members who would be in contact with the infant.

Attitudes to peripartum immunization

Most women (474 [93%]) expressed willingness to be immunized during pregnancy if discussed with them and recommended by their HCP; the remaining seven percent were evenly split between those who would refuse or who would require further reassurance and education. The overwhelming majority of women (97%) also considered cocooning to be a good or great idea. Most planned to receive the Tdap vaccine prior to discharge from hospital (79.4%), and 15% had either already received the vaccine during pregnancy, or had received it subsequent to a previous delivery at the hospital. Most also were supportive of the infant immunization schedule and 99% of the women planned that their baby would receive his/her scheduled vaccinations; data on whether they planned to use delayed or alternate infant immunization schedules were not collected.

When asked about the preferred locations for family members to receive vaccinations as part of infant cocooning, the overwhelming majority of women (97.2%) opted for clinic-based locations rather than pharmacies or supermarkets. The most accessible and convenient places were public clinics (32.3%), the hospital during postpartum stay (25.5%), pediatric clinics during well-child visits (24.3%), and prenatal clinics (15.1%). Specific barriers to successful cocooning stated by respondents included lack of education about the risks, benefits, and availability of vaccines (46.6%), financial constraints such as cost of vaccine, insurance co-payments or loss of earnings while attending clinic visits during the workday (31.4%), lack of transportation to locations where vaccines are offered (26.1%), and time constraints due to employment (13.3%). Fear of vaccination, or of needles were a likely concern for household contacts in the opinion of 70 women (13.7%).

Discussion

This study is one of the first to explore the acceptability of and barriers to targeted immunization strategies in the perinatal period. Despite the fact that influenza immunization during pregnancy and cocooning have been recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for some years, implementation rates are disappointing.21,22,28 These two strategies are central not only to prevention of influenza but also pertussis, and are important future platforms for efforts to reduce other vaccine-preventable disease-related mortality and morbidity globally. Understanding the needs and attitudes of the maternal and cocoon populations they target is critical to their success. This study demonstrates that in our cohort of largely Hispanic postpartum women, both immunization during pregnancy and cocooning are acceptable if recommended by HCPs. This finding mirrors experience from immunization studies in the pediatric population where, even among vaccine-hesitant parents, the most important factor governing parental decisions regarding immunization is their HCP.29-31

There was a high rate of willingness among survey participants to be immunized during pregnancy if this was recommended by their HCP. While it is certainly possible that attitudes reported postpartum would not fully reflect behavior while pregnant, the high vaccination coverage among those provided with targeted education (93%), suggests that in this population, improved education of and advocacy by providers would optimize immunization uptake. Interventions that include education have achieved higher influenza vaccination coverage in HCPs,32 and well-informed PNC providers who are supportive of maternal immunization are more likely to administer vaccines.19,33 Physicians, in particular, play a critical role in their patients’ immunization decisions and directly influence the odds of a woman receiving vaccines antenatally.18,21 During the 2010–2011 influenza season, for example, vaccination coverage was 5-fold higher in pregnant women offered influenza vaccine by their provider compared with those who were not, despite the fact that the vaccine was widely available in pharmacies, supermarkets and other locations in the community.21 Further, Broughton et al. reported that only 31% of ancillary obstetrical care providers (nurses, medical assistants and clinical administrators) believed influenza vaccine was safe and effective.17 Although the latter study preceded the H1N1 pandemic, it seems unlikely that attitudes among this group would have changed sufficiently in the intervening years to make them strong immunization advocates. The most efficient approach to maximizing maternal vaccination coverage would appear to be two-pronged by targeting physicians and other HCPs as well as pregnant women who place a high degree of trust in HCPs. This education should not only focus on the safety and efficacy of maternal immunization but also stress the benefits of this strategy since two individuals are protected with a single intervention.

The establishment of a cocooning platform also remains a priority. It is needed to protect infants born prematurely before efficient placental transfer of antibody has occurred, infants whose mothers were not immunized during pregnancy or whose antibody response is sub-optimal, and older infants in whom maternal-derived antibodies have waned.12,13,34 In this cohort, perceived barriers to cocooning were lack of information about this recommendation to protect young infants and financial constraints. Well-developed procedures exist in most health care systems to immunize infants and children at no cost to their parents; however, it is much more difficult and costly for adults to receive preventative care, including immunizations, for themselves. Providing information on when and where vaccines are available and choosing locales for vaccination that are convenient for parents—including public, pediatric, and prenatal clinics – would eliminate many of the barriers identified by this cohort. However, as noted in the few successful cocooning programs reported in the literature, education of HCPs also is critical in enabling families become well informed and this could and should be incorporated into routine PNC.23,26,27,35

There are several limitations to our study. First, our cohort was predominantly Hispanic ethnicity and underinsured, and thus may not be representative of the attitudes of other ethnicities or socio-economic groups. Second, as pertussis incidence and mortality, one of the main targets of these immunizations strategies, is over-represented in Hispanic infants, it is possible that relatively more subjects have personal experience of the effects of this illness, resulting in bias in their responses. These limitations should not affect provider education of subjects, because, if anything this population should be more likely to be immunized given their acknowledged high-risk status. Third, we surveyed mothers postpartum and a woman’s voiced acceptance of maternal immunization after the birth of a healthy infant may be higher than if they were surveyed antenatally. Fourth, there may be inaccurate recall of provider-patient conversations during the antenatal period. Even allowing for these limitations, however, we believe this study represents a first step in understanding the acceptance and needs of a population likely to benefit most from these two targeted immunization strategies.

In conclusion, mothers and their young infants remain at risk for morbidity and mortality from vaccine-preventable diseases. Maternal immunization is safe, has resulted in maternal and neonatal tetanus elimination in many resource-poor nations, and reduces maternal and infant influenza-related illness.1,3,15,20,36-40 This “two for one” strategy also contributes to community immunity and is the cornerstone of the protective cocoon, which also is necessary to protect infants through the period of highest risk of morbidity from these infections. The establishment of effective maternal immunization and cocooning platforms come with the expectation of public health benefits once high vaccination coverage is achieved. This study represents one of the first steps in achieving this aim, because it is only through understanding the views of the targeted population and identifying educational and other needs that suitable interventions can occur.

Patients and Methods

Study population

The survey was conducted among postpartum women at BTGH, Houston, Texas. The survey was developed by the study team and pilot tested among immunizations specialists and nurses and physicians caring for postpartum women and newborn infants. The survey determined participant demographics, knowledge of immunization recommendations for pregnant women and caregivers of infants, sources of information about perinatal health and the level of trust placed in each source, and perceived barriers to receiving immunizations. A random, convenience sample of postpartum women, aged 18 y and older, delivering at BTGH were invited to complete our survey. Postpartum women were given a letter explaining the survey and asked if they were interested in participating. Women who expressed an interest then completed the verbally-administered survey administered by a nurse or educator associated with the Tdap cocooning program. Surveys were administered in English or Spanish depending on participant preference. Education on immunization recommendations for each participant was provided after the survey was completed, and was also provided for women who declined participation. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of both Baylor College of Medicine and the Harris Health System.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Descriptive characteristics of participants were assessed. Data were analyzed to define whether knowledge and attitudes varied by formal educational status, number of children, insurance status and type of healthcare provider. Statistical significance for dichotomous outcomes was determined by chi square and Fisher exact tests. Normally distributed data were assessed by means and the Student’s t test; where positive or negative skewing of data occurred, statistical significance was assessed by medians and the Mann-Whitney U test. Where appropriate, multiple logistic regression analysis assessed the significance of variables.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of Ben Taub General Hospital, Houston, TX for their co-operation and assistance in performing this study, Nancy Ng, BSN, RN (Center for Vaccine Awareness and Research, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX) for assistance in data collection, and Robin Schroeder (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX) for assistance in preparing this manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- BTGH

Ben Taub General Hospital

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- HCP

healthcare providers

- PNC

prenatal care

- Tdap

Combined tetanus, diphtheria and acellular pertussis

Disclosures

CMH is the recipient of research grants from Sanofi Pasteur and Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics and serves on an Advisory Board for Novartis Vaccines. All other authors have no disclosures.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/vaccines/article/25096

References

- 1.Healy CM. Vaccines in pregnant women and research initiatives. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55:474–86. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31824f3acb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mosby LG, Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ. 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in pregnancy: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:10–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neuzil KM, Mellen BG, Wright PF, Mitchel EF, Jr., Griffin MR. The effect of influenza on hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and courses of antibiotics in children. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:225–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001273420401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhat N, Wright JG, Broder KR, Murray EL, Greenberg ME, Glover MJ, et al. Influenza Special Investigations Team Influenza-associated deaths among children in the United States, 2003-2004. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2559–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanaka M, Vitek CR, Pascual FB, Bisgard KM, Tate JE, Murphy TV. Trends in pertussis among infants in the United States, 1980-1999. JAMA. 2003;290:2968–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.22.2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vitek CR, Pascual FB, Baughman AL, Murphy TV. Increase in deaths from pertussis among young infants in the United States in the 1990s. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:628–34. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000073266.30728.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winter K, Harriman K, Zipprich J, Schechter R, Talarico J, Watt J, et al. California pertussis epidemic, 2010. J Pediatr. 2012;161:1091–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Pertussis--United States, 1997-2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:73–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Summary of notifiable diseases--United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;59:1–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Healy CM, Baker CJ. Prospects for prevention of childhood infections by maternal immunization. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2006;19:271–6. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000224822.65599.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaman K, Roy E, Arifeen SE, Rahman M, Raqib R, Wilson E, et al. Effectiveness of maternal influenza immunization in mothers and infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1555–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in pregnant women and persons who have or anticipate having close contact with an infant aged <12 months --- Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1424–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)--United States, 2012-13 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:613–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in pregnant women--Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:131–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for Vaccinating Pregnant Women. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/preg-guide.htm Accessed January 11, 2013.

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Noninfluenza vaccination coverage among adults - United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:66–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broughton DE, Beigi RH, Switzer GE, Raker CA, Anderson BL. Obstetric health care workers’ attitudes and beliefs regarding influenza vaccination in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:981–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181bd89c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esposito S, Tremolati E, Bellasio M, Chiarelli G, Marchisio P, Tiso B, et al. V.I.P. Study Group Attitudes and knowledge regarding influenza vaccination among hospital health workers caring for women and children. Vaccine. 2007;25:5283–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Englund JA. Maternal immunization with inactivated influenza vaccine: rationale and experience. Vaccine. 2003;21:3460–4. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00351-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mak TK, Mangtani P, Leese J, Watson JM, Pfeifer D. Influenza vaccination in pregnancy: current evidence and selected national policies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:44–52. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women --- United States, 2010-11 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1078–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:13–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Healy CM, Rench MA, Baker CJ. Implementation of cocooning against pertussis in a high-risk population. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:157–62. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Healy CM, Rench MA, Castagnini LA, Baker CJ. Pertussis immunization in a high-risk postpartum population. Vaccine. 2009;27:5599–602. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah SI, Caprio M, Hendricks-Munoz K. Administration of inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine to parents of high-risk infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e617–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan TQ, Gerbie MV. Pertussis and patient safety: implementing Tdap vaccine recommendations in hospitals. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36:173–8. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(10)36029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walter EB, Allred N, Rowe-West B, Chmielewski K, Kretsinger K, Dolor RJ. Cocooning infants: Tdap immunization for new parents in the pediatric office. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:344–7. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Influenza vaccination in pregnancy: practices among obstetrician-gynecologists--United States, 2003-04 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:1050–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith PJ, Kennedy AM, Wooten K, Gust DA, Pickering LK. Association between health care providers’ influence on parents who have concerns about vaccine safety and vaccination coverage. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1287–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salmon DA, Moulton LH, Omer SB, DeHart MP, Stokley S, Halsey NA. Factors associated with refusal of childhood vaccines among parents of school-aged children: a case-control study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:470–6. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.5.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freed GL, Clark SJ, Butchart AT, Singer DC, Davis MM. Sources and perceived credibility of vaccine-safety information for parents. Pediatrics. 2011;127(Suppl 1):S107–12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1722P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hofmann F, Ferracin C, Marsh G, Dumas R. Influenza vaccination of healthcare workers: a literature review of attitudes and beliefs. Infection. 2006;34:142–7. doi: 10.1007/s15010-006-5109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tong A, Biringer A, Ofner-Agostini M, Upshur R, McGeer A. A cross-sectional study of maternity care providers’ and women’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours towards influenza vaccination during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008;30:404–10. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)32825-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Healy CM, Baker CJ. Infant pertussis: what to do next? Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:328–30. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dylag AM, Shah SI. Administration of tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine to parents of high-risk infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e550–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brent RL. Risks and benefits of immunizing pregnant women: the risk of doing nothing. Reprod Toxicol. 2006;21:383–9. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Munoz FM, Greisinger AJ, Wehmanen OA, Mouzoon ME, Hoyle JC, Smith FA, et al. Safety of influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1098–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Omer SB, Goodman D, Steinhoff MC, Rochat R, Klugman KP, Stoll BJ, et al. Maternal influenza immunization and reduced likelihood of prematurity and small for gestational age births: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization. Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus (MNT) Elimination. Available at www.who.int/immunization_monitoring/diseases/MNTE_initiative/en/index.html Accessed January 11, 2013.

- 40.Poehling KA, Szilagyi PG, Staat MA, Snively BM, Payne DC, Bridges CB, et al. New Vaccine Surveillance Network Impact of maternal immunization on influenza hospitalizations in infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(Suppl 1):S141–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]