To the Editor,

Gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) is the most common soft-tissue sarcoma, with reported annual incidence of 14–20 cases per million [1,2]. Approximately half of the patients will relapse within five years despite complete surgical resection [3]. Standard chemotherapy and radiotherapy are not effective, but the majority of patients with locally advanced or metastatic GIST respond to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib [4], however, are seldomly cured [5]. Approximately 15% of GISTs are primarily imatinib-resistant and most responders develop secondary resistance to imatinib [5]. Adverse effects of imatinib are dose-dependent and especially patients with large tumour burden and poor general condition are exposed. Early treatment assessment may contribute to a more individualised treatment regime, avoiding ineffective treatment and unnecessary toxicity.

Traditionally, computed tomography (CT) and the response evaluation criteria in solid tumours (RECIST) [6] have been used for the assessment of treatment response in GIST patients. Based solely on measurements of tumour size, functional and metabolic responses are not included. When imaged by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET) most GISTs show high metabolic activity (high uptake of 18F-FDG) [7], and treatment response can be observed as reduced uptake as early as 24 hours after onset of TKI treatment [8]. About 20% of untreated GISTs may, however, be without visibly increased 18F-FDG uptake and still be overtly malignant [9]. Furthermore, 18F-FDG PET is a costly examination with limited availability. Recently, diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DW MRI) has been applied for monitoring tumour response following therapeutic interventions [10]. Malignant tumours usually show high signal intensity on DW MRI because of high cellular density and limiting the freedom of water molecules to move [11]. The diffusion in tissue can be quantified by calculation of the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), inversely related to the DW MRI signal intensity. During TKI treatment the cellular density is anticipated to decrease. The decrease is reflected by an increasing tumour ADC [11]. The magnitude of ADC increase will depend on tumour cell death, remodelling of tissues, vascular normalisation, development of fibrosis, and phagocytosis of dead cells. We recently published a case where DW MRI was used for both the initial diagnosis and for the assessment of treatment response in a rectal GIST patient receiving imatinib [12]. Tang et al. have investigated the use of the diffusion coefficient separately as an early response indicator in these patients, without comparison to other functional modalities [13].

The aim of this study was to explore the feasibility of DW MRI, 18F-FDG PET/CT and CT to detect early response in GIST patients treated with imatinib.

Material and methods

Ten consecutive patients (mean age; 69 years, range 41–91 years) referred to our institution for imatinib treatment were included between February 2011 and April 2012. The 10 GISTs were either locally advanced (considered surgically unresectable, n = 3) or had given rise to distant metastasis (n = 7). The study (ClinicalTrials identifier NCT01276483) was approved by the regional medical ethics committee and written informed consent was obtained. Patient and tumour characteristics are summarised in Table I.

Table I.

Patient and tumour characteristics.

| Age | |

| Median | 69 years |

| Range | 41–91 years |

| Gender | |

| Male | 8 |

| Female | 2 |

| Primary | |

| Stomach | 6 |

| Small intestine | 4 |

| Tumour size | |

| Median (mm) | 39 |

| Range (mm) | 20–222 |

| Metastases | |

| Liver | 4 |

| Intra-abdominal | 2 |

| Liver and intra-abdominal | 1 |

| No metastases | 3 |

| Mitotic index | |

| < 5/50 HPF | 7 |

| ≥ 5/50 HPF | 3 |

| Mutation analysis | |

| KIT exon 11 | 9 |

| KIT exon 9 | 1 |

| Imatinib dosage | |

| 200 mg | 2 |

| 400 mg | 7 |

| 800 mg | 1 |

DW MRI, 18F-FDG PET/CT and CT were performed 2–4 days prior to (Tp0) and early after onset of imatinib treatment (range 8–18 days, Tp1). All imaging procedures at Tp0 and Tp1 were performed on the same day. Late treatment outcome was defined as change in longest tumour diameter at CT between Tp0 and after three months of imatinib treatment (Tp2), categorised according to RECIST [6].

Early changes in imaging parameters according to RECIST, the Choi criteria and the positron emission tomography response criteria in solid tumours PERCIST between Tp0 and Tp1 were compared to late treatment outcome.

The imaging protocols and detailed information about image review and response assessment can be found in Appendix 1 ‘Imaging and review protocols’ (Appendix 1 available online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2013.798428).

Results

Ten GIST patients with a total of 15 lesions were included in this study. All individual image findings can be found in Appendix 2 ‘Imaging findings’ (Appendix 2 available online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2013.798428). At Tp0, median longest tumour diameter was 39 mm (range 20–222 mm). Mean reduction in the longest tumour diameter at Tp1 and Tp2 was 13% (range 19–42%) and 32% (range 216–45%), respectively.

Classification of treatment response according to the different sets of response criteria are summarised in Table II. At Tp1, only three patients (patients 3, 6 and 10) were classified as responders according to RECIST [6], whereas at Tp2, all except two patients with stable disease (patients 1 and 2), were classified as responders.

Table II.

Treatment response according to different sets of response criteria.

| Patient | Tp1 |

Tp2 mRECIST |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADC | PERCIST | Choi | mRECIST | ||

| 1 | NR | R | NA | SD | SD |

| 2 | NR | R | NR | SD | SD |

| 3 | R | R | R | PR | PR |

| 4 | R | NA | NA | PD | PR |

| 5 | R | R | R | SD | PR |

| 6 | R | R | R | PR | PR |

| 7 | NR | R | R | SD | PR |

| 8 | R | NA | R | SD | PR |

| 9 | R | NA | NR | SD | PR |

| 10 | R | R | R | PR | PR |

NA, not applicable; NR, non-responders; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; R, responders; SD, stable disease.

The difference between SUVmean in the right liver lobe (circular ROI of 3 cm diameter) at Tp0 (mean; 1.63, range 1.1–2.0) and Tp1 (mean; 1.59, range 1.2–2.1) was less than 0.2 units for all 10 patients. Thus, treatment-induced changes detected at 18F-FDG PET can be assessed with high reliability.

In three patients with a total of four lesions (patients 4, 8 and 9) the 18F-FDG uptake in the lesions was lower than the surrounding background activity. These patients (longest baseline diameters of 20–44 mm) were therefore excluded from further 18F-FDG PET analyses. For the remaining seven patients, median SUVmax at baseline was 9.5 (range 4–13.8). At Tp1, mean SUVmax was reduced by 78% (range 48–96%). Five of the seven patients showing metabolic response at Tp1 were classified as responders according to RECIST at Tp2. For patients 1 and 2 the decrease of 72% and 96% in SUVmax at Tp1 was not followed by tumour shrinkage at Tp2. Thus, late response was correctly predicted by 18F-FDG PET at Tp1 in five of 10 patients.

At Tp0, median attenuation was 69.5 HU (range 29–80 HU). At Tp1 the mean attenuation coefficient was reduced by 20% (range −21–70%). The two patients without contrast-enhanced CT were excluded since the Choi criteria require measurements in the portal-venous phase. Of the remaining eight patients four showed a decrease in CT density value above the cut-off (> 15%) for response according to the Choi criteria (patients 3, 5, 6 and 7). By including a size reduction of > 10% as defined in the Choi criteria two more patients were classified as responders (patients 8 and 10).

Median ADC at Tp0 was 0.8 × 10−3 mm2/s (range 0.5–1.7 mm2/s). At Tp1, mean ADC was increased by 64% (range 13–140%). For three patients the ADC at Tp1 indicated no treatment response (ADC increase < 30%): For patient 2 the 13% decrease at Tp1 was followed by a slight increase in longest tumour diameter at Tp2 (6.5%). Patient 7 showed unchanged ADC at Tp1, but had a reduction of MRI tumour volume and the longest tumour diameter at CT of 45% and 42% at Tp2, respectively. Patient 1 showed insufficient ADC increase (25%) and a minor reduction in MRI volume (20%), longest tumour diameter and histological assessment at Tp2 indicated stable disease. The three patients with four non-18F-FDG avid lesions all showed ADC increase > 30% (130%, 29/50% and 86%, respectively) at Tp1. Thus, ADC correctly predicted treatment response in nine of 10 patients.

All patients with 18F-FDG avid lesions (n = 7) at Tp0 were responders at Tp1 according to PERCIST. Using the Choi criteria at Tp1, two patients were non-responders whereas the others met the criteria of response. The RECIST, the Choi criteria and the PERCIST were concordant in only two patients at Tp1 (patients 6 and 10) (Table II).

Discussion

This study indicates that DW MRI at an early stage can predict treatment outcome in GIST patients receiving imatinib. Established response criteria for CT and 18F-FDG PET/CT did not provide the same correctness.

The usefulness of size-based criteria alone for assessment of initial response is limited as early change in tumour size has proven not predictive of ultimate response [14]. Additional CT parameters such as attenuation measurements may provide useful information, and the combination of decrease in tumour size and decrease in density has been found to be valuable parameters for the evaluation of response to imatinib treatment for GIST patients (the Choi criteria) [9]. In the present study, only three of 10 patients had partial response at Tp1 according to RECIST, but by including the Choi criteria five more patients were correctly categorised as responders.

18F-FDG PET/CT is claimed to be the modality of choice for the evaluation of treatment response to imatinib [15]. Even though most GISTs show increased 18F-FDG-uptake, some GISTs do not show sufficient 18F-FDG uptake to be detected by PET [9]. In general, PETs ability to detect small lesions may be limited by the spatial resolution and physiologic background activity. Choi et al. reported that 36 of 173 (21%) lesions did not have detectable 18F-FDG uptake on pre-treatment PET and that 17 of these were more than 20 mm in diameter [9]. In the present study, lesions in three of 10 patients were not detected by 18F-FDG PET (Figure 1; patient 9). None of these lesions were less than 20 mm; median diameter was 39 mm. A dynamic acquisition might improve the performance of 18F-FDG PET as an early biomarker for response. Clinically relevant information, such as blood flow, exchange rates, phosphorylation and dephosphorylation rates can be extracted from a dynamic acquisition. In the current study, the early changes in SUVmax for the 18F-FDG avid lesions were of great magnitude and easily detected. However, in two patients (patients 1 and 2) the marked decrease in SUVmax was not followed by a reduction in tumour diameter after three months and both were therefore classified as having stable disease according to RECIST. For one of these patients, stable disease was conformed at six months follow-up imaging (patient 2). The other patient underwent liver resection of a solitaire metastasis after 11 weeks of imatinib treatment (patient 1). Microscopic evaluation showed decreased cellularity and increased amounts of collagenous fibres compared to the primary tumour, but minimal necrosis. The histological response was graded as low, > 10% and ≤ 50% response supportive of stable disease. The pronounced reduction in 18F-FDG uptake observed in these two patients clearly qualifies as responders at PET. Previous studies have shown that both imatinib responders and patients attaining disease stabilisation have similar survival outcome [16,17] and thus the importance of distinguishing between responders and those with stable disease may be artificial.

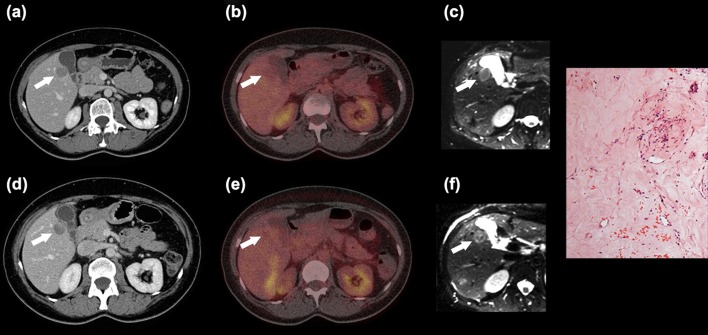

Figure 1.

Forty-seven-year-old woman with metastatic GIST. Patient 9: Liver metastasis (white arrow) at CT (a,d), 18F-FDG PET/CT (b,e) and ADC map (c,f) before (a–c) and after 12 days of imatinib treatment (d–f). The attenuation was almost unchanged at CT. 18F-FDG uptake was indistinguishable from liver parenchyma (already before treatment). At MRI the mean value and the range of ADCs increased substantially, indicating good response. Microscopic examination of the resected metastatic liver lesion showed scattered tumour cells within fibrous tissue. There were two mitotic figures/50 high power fields. The tumour cells were positive for CD117 and DOG1. The histological response was > 10% and ≤ 50%.

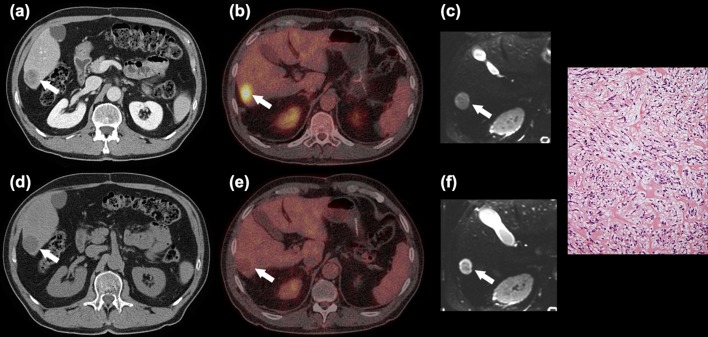

Complete metabolic response at 18F-FDG PET has frequently been reported in GIST patients, however, curative treatment with imatinib is rare [5]. A negative 18F-FDG PET after treatment often suggests good treatment response but does not indicate absence of cancer cells [18] (Figure 2; patient 1). A 30% decrease in SUV, as proposed as threshold for response in the PERCIST does not necessarily predict favourable outcomes in GIST patients treated with imatinib [14,15]. In the present study all patients received imatinib, and the mean decrease in 18F-FDG-avid lesions was 78% supporting previous reports which suggested that a higher threshold than proposed in PERCIST may be appropriate [14].

Figure 2.

Sixty-seven-year-old man with metastatic GIST. Patient 1: Liver metastasis (white arrow) at CT (a,d), 18F-FDG PET/CT (b,e) and ADC map (c,f) before (a-c) and after 12 days of imatinib treatment (d-f). 18F-FDG PET/CT showed a decrease in SUVmax indicating good response, whereas ADC increase indicated only minor response (ADC increased from 1.2 to 1.5 × 10−3 mm2/s). Microscopic examination of the resected liver lesion showed moderate cellularity, minimal necrosis and large amounts of collagenous fibres without visible mitotic figures. The tumour cells were positive for CD117 and DOG1. The histological response was low > 10 and ≤ 50%.

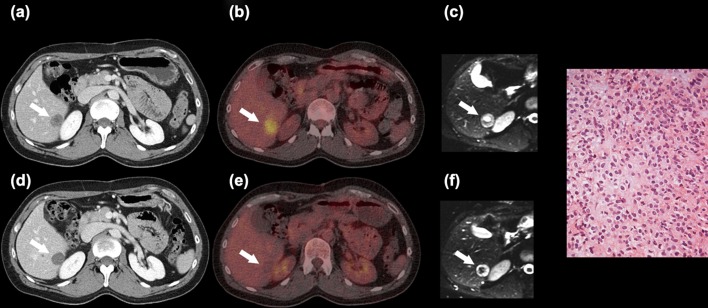

Compared to 18F-FDG PET and CT, DW MRI does not rely on the use of ionising radiation, there is no need for administration of contrast agent or radioactivity, and the examination can be carried out in a few minutes. Furthermore, MRI has the advantage of being more available, offers easier examination logistics and lower cost than does 18F-FDG PET. Both preclinical and clinical studies have shown that ADC increase as early as 3–11 days after initiating treatment are correlated to treatment outcome [19,20]. However, increases in ADC as a result of tumour cell death may not be a prolonged phenomenon and will with time fall due to vascular normalisation, phagocytosis of dead cells, remodelling of tissues and development of fibrosis [10]. Imatinib has some antiangiogenetic effects [21] and may induce reduction in blood and extracellular space, which prevent water movement in the extracellular space resulting in an initial decreased ADC [11]. Subsequent tumour necrosis following antivascular treatment causes an increased ADC. Thus, there may be a limited time window where an increase in ADC is a usable criterion for treatment response (Figure 3, patient 2). A major challenge for DW MRI is the lack of standardisation of acquisition, measurement and analysis and the fact that there are no internationally accepted definitions for response on DW MRI. Furthermore, the threshold of changes in ADC corresponding with a true treatment effect has not been established. Reproducibility studies have shown that ADC may vary with up to 29% between consecutive DW MRI examinations [22–24]. We therefore defined responders as patients with an ADC increase of > 30% at Tp1. A large early reduction in tumour volume for patient 7 (45%) may have masked an increase in ADC (patient 7) and thus lead to misclassification of ADC-response at Tp1.

Figure 3.

Forty-one-year-old man with metastatic GIST. Patient 2: Liver metastasis (white arrow) at CT (a,d), 18F-FDG PET/CT (b,e) and ADC map (c,f) before (a–c) and after 12 days of imatinib treatment (d–f). Reduction in attenuation on CT and of SUVmax on 18F-FDG PET/CT. ADC changed from values reflecting peripheral solid tumour and central necrosis into values indicating peripheral necrosis and central fibrosis. Stable disease was observed at six month follow-up imaging. Microscopic examination of a needle biopsy from the liver prior to imatinib treatment showed a moderately cellular GIST metastasis. The biopsy was positive for CD117 and DOG1 on immunohistochemistry. No post-treatment tumour tissue was available for examination.

Tang et al. recently reported that the largest difference in ADC change between responders and non-responders was observed after one week of imatinib treatment; median ADC increase of 44.8% and 1.5% for the responders and non-responders, respectively. In the current study, a median increase for responders was 75% (mean 64%) after 12 days of imatinib treatment [13].

Growth pattern and biological heterogeneity of GISTs and their variable response to imatinib treatment challenge the interpretation of images from these patients. In-depth knowledge of the physical principles underlying image information is essential for evaluation of treatment response. In cases where tumour is intermixed with benign tissue and the tumour consists of several tissue components (Figure 1; patient 9) image values obtained for the entire lesion may be of limited clinical value, as the response to treatment may be different for different components. Isolated use of mean ADC could mask tissue heterogeneity and be misleading (Figure 3; patient 2). Histogram analysis may increase the predictive outcome of ADC measurements. Furthermore, qualitatively assessment of DW MRI using high b value images may detect focal areas of residual tumour [11].

In conclusion, nine of 10 patients could be correctly identified at an early stage by altered ADC, illustrating the potential of this technique for monitoring treatment response in GISTs following imatinib therapy. Our aim is to confirm these findings in the ongoing prospective clinical trial (ClinicalTrials identifier NCT01276483) with special emphasis on the establishment of optimal time-point for imaging and treatment response criteria.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank physicist Line Ausland Refsum for advice and the bioengineers of The Department of Nuclear Medicine for their help in performing the study. This study received financial support from The Norwegian Radium Hospital Research Foundation.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Supplementary material available online

Appendix 1. Imaging and review protocols.

Appendix 2. Imaging findings.

References

- 1.Nilsson B, Bumming P, Meis-Kindblom JM, Oden A, Dortok A, Gustavsson B, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: The incidence, prevalence, clinical course, and prognostication in the preimatinib mesylate era – a population-based study in western Sweden. Cancer. 2005;103:821–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steigen SE, Eide TJ. Trends in incidence and survival of mesenchymal neoplasm of the digestive tract within a defined population of northern Norway. APMIS. 2006;114:192–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2006.apm_261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samiian L, Weaver M, Velanovich V. Evaluation of gastrointestinal stromal tumors for recurrence rates and patterns of long-term follow-up. Am Surg. 2004;70:187–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casali PG, Blay JY. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21((Suppl 5)):98–102. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanke CD, Rankin C, Demetri GD, Ryan CW, von MM, Benjamin RS, et al. Phase III randomized, intergroup trial assessing imatinib mesylate at two dose levels in patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing the kit receptor tyrosine kinase: S0033. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:626–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.4452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Treglia G, Mirk P, Stefanelli A, Rufini V, Giordano A, Bonomo L. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in evaluating treatment response to imatinib or other drugs in gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A systematic review. Clin Imaging. 2012;36:167–75. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shinto A, Nair N, Dutt A, Baghel NS. Early response assessment in gastrointestinal stromal tumors with FDG PET scan 24 hours after a single dose of imatinib. Clin Nucl Med. 2008;33:486–7. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e31817792a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi H. Response evaluation of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Oncologist. 2008;13((Suppl 2)):4–7. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.13-S2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Padhani AR, Koh DM. Diffusion MR imaging for monitoring of treatment response. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2011;19:181–209. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charles-Edwards EM, de Souza NM. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and its application to cancer. Cancer Imaging. 2006;6:135–43. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2006.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Revheim ME, Hole KH, Bruland OS, Haugland HK, Hall KS, Seierstad T. DW MRI for evaluation of treatment response to imatinib in a rectal gastrointestinal stromal tumour. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:148–50. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.516273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang L, Zhang XP, Sun YS, Shen L, Li J, Qi LP, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors treated with imatinib mesylate: Apparent diffusion coefficient in the evaluation of therapy response in patients. Radiology. 2011;258:729–38. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stroobants S, Goeminne J, Seegers M, Dimitrijevic S, Dupont P, Nuyts J, et al. 18FDG-Positron emission tomography for the early prediction of response in advanced soft tissue sarcoma treated with imatinib mesylate (Glivec) Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:2012–20. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van den Abbeele AD, Gatsonis C, de Vries DJ, Melenevsky Y, Szot-Barnes A, Yap JT, et al. ACRIN 6665/RTOG 0132 phase II trial of neoadjuvant imatinib mesylate for operable malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor: Monitoring with 18F-FDG PET and correlation with genotype and GLUT4 expression. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:567–74. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.094425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blanke CD, Demetri GD, von MM, Heinrich MC, Eisenberg B, Fletcher JA, et al. Long-term results from a randomized phase II trial of standard- versus higher-dose imatinib mesylate for patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing KIT. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:620–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.4403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demetri GD, von MM, Blanke CD, Van den Abbeele AD, Eisenberg B, Roberts PJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of imatinib mesylate in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:472–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corless CL, Barnett CM, Heinrich MC. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: Origin and molecular oncology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:865–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc3143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui Y, Zhang XP, Sun YS, Tang L, Shen L. Apparent diffusion coefficient: Potential imaging biomarker for prediction and early detection of response to chemotherapy in hepatic metastases. Radiology. 2008;248:894–900. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2483071407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seierstad T, Folkvord S, Roe K, Flatmark K, Skretting A, Olsen DR. Early changes in apparent diffusion coefficient predict the quantitative antitumoral activity of capecitabine, oxaliplatin, and irradiation in HT29 xenografts in athymic nude mice. Neoplasia. 2007;9:392–400. doi: 10.1593/neo.07154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin T, Nakatani H, Taguchi T, Nakano T, Okabayashi T, Sugimoto T, et al. STI571 (Glivec) suppresses the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in the gastrointestinal stromal tumor cell line, GIST-T1. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:703–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braithwaite AC, Dale BM, Boll DT, Merkle EM. Short- and midterm reproducibility of apparent diffusion coefficient measurements at 3.0-T diffusion-weighted imaging of the abdomen. Radiology. 2009;250:459–65. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2502080849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SY, Soo LS, Bumwoo P, Kim N, Kim JK, Park SH, et al. Reproducibility of measurement of apparent diffusion coefficients of malignant hepatic tumors: Effect of DWI techniques and calculation methods. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;36:1131–8. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miquel ME, Scott AD, Macdougall ND, Boubertakh R, Bharwani N, Rockall AG. In vitro and in vivo repeatability of abdominal diffusion-weighted MRI. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:1507–12. doi: 10.1259/bjr/32269440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.