Abstract

Bacteria and plant derived volatile organic compounds have been reported as the chemical triggers that elicit induced resistance in plants. Previously, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), including acetoin and 2,3-butanediol, were found to be emitted from plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) Bacillus subtilis GB03, which had been shown to elicit ISR and plant growth promotion. More recently, we reported data that stronger induced resistance could be elicited against Pseudomonas syringae pv maculicola ES4326 in plants exposed to C13 VOC from another PGPR Paenibacillus polymyxa E681 compared with that of strain GB03. Here, we assessed whether another long hydrocarbon C16 hexadecane (HD) conferred protection to Arabidopsis from infection of a biotrophic pathogen, P. syringae pv maculicola and a necrotrophic pathogen, Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp carotovorum. Collectively, long-chain VOCs can be linked to a plant resistance activator for protecting plants against both biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens at the same time.

Keywords: PGPR, Paenibacillus polymyxa, Pseudomonas syringae, induced systemic resistance, volatile organic compound

The group of root-colonizing bacteria that is called as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) confers beneficial effects to plants, including induction of systemic resistance (ISR) against phytopathogens and herbivores.1-3 Many bacterial determinants for such mechanism from PGPR have been discovered.4,5 Previous research suggested that components of the bacterial cell membrane and some secondary metabolites contributed to ISR.1-3,6 In 2003, bacterial volatiles produced from Bacillus subtilis strain GB03 were found to act as a determinant for ISR.7-9 Out of > 30 volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from strain GB03, a C4 hydrocarbon 2,3-butanediol played a critical role in ISR against Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp carotovorum. A later study revealed that ethylene signaling was essential for elicitation of ISR using PDF1.2 and Jin14 indicator genes for ethylene/jasmonate and jasmonate signaling, respectively.7 Application of volatiles from strain GB03 upto Arabidopsis seedlings also caused decrease of disease severity caused by P. carotovorum subsp carotovorum. In addition to promoting ISR, strain GB03 volatiles elicited an environmental stress resistance against salt by modulating sodium homeostasis in the Arabidopsis root.10 Similarly, 2,3-butanediol, emitted from the Gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas chlororaphis O6, caused stomatal closure resulting in drought resistance.11 Moreover, the same authors indicated 2,3-butanediol did not effectively induce ISR against Pseudomonas syringae pv tabaci but found it did successfully suppress soft-rot development caused by P. carotovorum in tobacco.12 Taken together, 2,3-butanediol did not triggers strong ISR against biotropic bacteria but did against necrotrophic bacteria.

In a search for novel PGPR strains, Paenibacillus polymyxa E681 was selected for a promising PGPR that can be utilized as a biocontrol agent and a yield increasing bacterium in different crop species such as cucumber, sesame and pepper plants.2,13,14 One of the possible explanations for strain E681-mediated enhancement of plant growth and inhibition of plant diseases is the production of the plant hormones auxin and cytokinin and secondary metabolites polymyxin and 2,3-butanediol.15-17

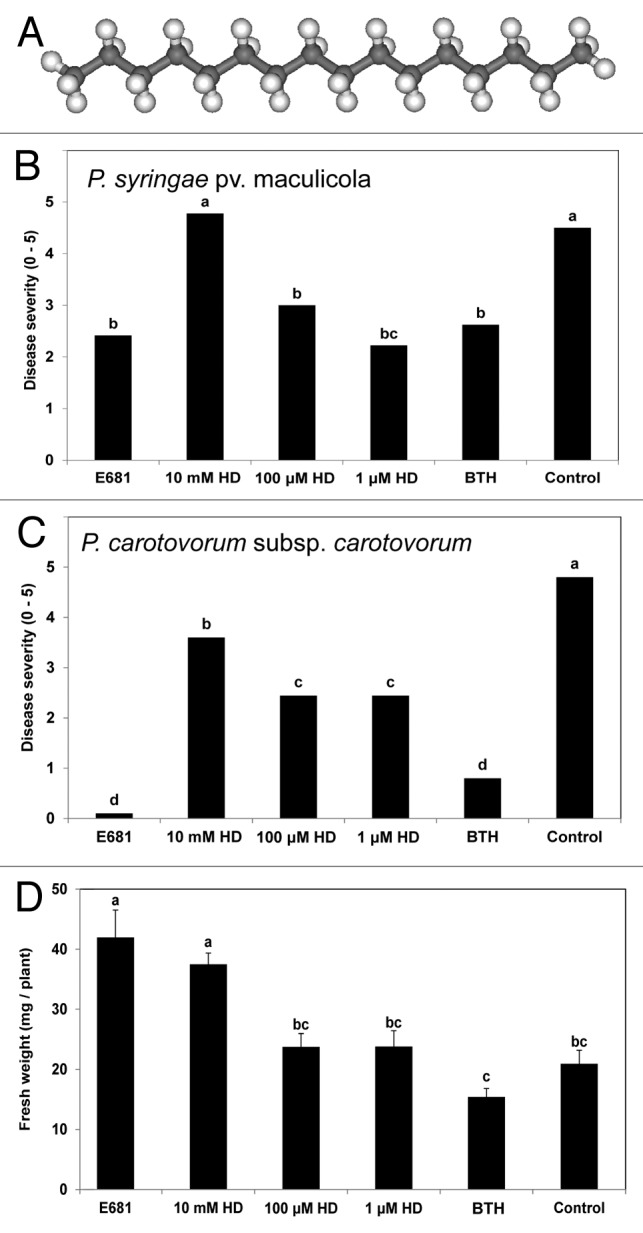

Here, our objective was to examine if volatiles from P. polymyxa E681 could elicit ISR against both necrotrophic and biotrophic pathogens. A C16 VOC, hexadecane, was produced only by strain E681 through the careful assessment of the volatiles emitted from two different Bacillus spp. and strain E681 (Fig. 1A). Our results identified a novel hydrocarbon-based signal molecule from strain E681 as the bacterial determinant(s) involved in ISR in plants.

Figure 1. Induced systemic resistance against Pseudomonas syringae pv maculicola ES4326 and Penctobacterium carotovorum subsp carotovorum and plant growth promotion by Paenibacillus polymyxa E681 and bacterial volatile hexadecane. (A) Chemical structure of hexadecane. (B) Induced systemic resistance against P. syringae pv maculicola ES4326 elicited by P. polymyxa E681, 10 mM, 100 μM and 1 μM hexadecane and 0.33 mM BTH using the I-plate system. Disease severity (0 = no symptom, 5 = severe chlorosis) was recorded seven days after pathogen challenge at 108 cfu/ml on the leaves at 7 d after application of strain E681 and chemicals in roots. (C) Induced systemic resistance against P. carotovorum subsp carotovorum SCC1 elicited by P. polymyxa E681, 10 mM, 100 μM and 1 μM hexadecane and 0.33 mM BTH using the I-plate system. Disease severity (0 = no symptom, 5 = complete soft-rot) was recorded 24 h after drop-inoculation of pathogen at 107 cfu/ml. (D) Plant growth responses by by P. polymyxa E681, 10 mM, 100 μM and 1 μM hexadecane and 0.33 mM BTH using the I-plate system. Sterile distilled water used as “control.” Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments, according to least significant difference at p = 0.05.

The pharmaceutical application of hexadecane in the I-plate system confer ISR in Arabidopsis against P. syringae pv maculicola ES4326 as a biotrophic bacterium at seven day-post inoculation and P. carotovorum subsp carotovora SCC1 as a necrotrophic bacterium at 24 h after drop-inoculation.7 Previously, indirect application (physical separation between plant and treatment) of any bacterial volatiles did not induce systemic resistance against any biotrophic pathogenic bacteria. In this study, we obtained the new evidence that release of hexadecane can significantly ISR against P. syringae pv maculicola ES4326 (Fig. 1B). The different concentrations of hexadecane showed different effects against P. syringae in comparison with P. carotovorum. The highest concentration of hexadecane (10 mM) did not induce ISR against P. syringae, although it did against P. carotovorum (Fig. 1B). However, disease severity in Arabidopsis seedlings exposed to 100 μM and 1 μM hexadecane was significantly different from 10 mM hexadecane treatment. The indirect treatment of 0.33 mM benzothiadiazole (BTH) reduced symptom development when compared with control (Fig. 1B and C). In addition, it is noteworthy that no concentration of hexadecane negatively affected plant growth, indicating that hexadecane from VOCs produced by strain E681 plays a role only in ISR. The foliar fresh weights of Arabidopsis seedlings were significantly increased by treatment with strain E681 and 10 mM HD compared with water control (Fig. 1D). The treatments of 0.33 mM BTH and 100 μM and 1 μM HD did not result in significantly higher foliar fresh weights compared with the control (Fig. 1D).

To assess induction of defense gene expression of three marker genes, Pathogenesis-Related gene 1 (PR1) for salicylic acid signaling, PDF1.2 for jasmonic acid signaling and ChiB for ethylene signaling.18 Quantitative RT-PCR technique was applied 0 and 6 h post inoculation of hexadecane into roots and at 0 and 3 h post pathogen challenge on the leaves. Direct application of 0.35 mM hexadecane on the plant roots significantly increased PR1 gene expression but did not increase PDF1.2 and ChiB gene expressions (data not shown). A hexadecane dose of 0.35 mM, which had the most consistent results across different concentrations of hexadecane, did not show defense priming on the three defense genes (data not shown). The hexadecane treatment upregulated transcription of PR1 gene in the leaves at a level 4,000-fold higher at 6 h after direct treatment into roots and maintained transcription at lower levels up to 100-fold when pathogen challenged (data not shown).

Using by plant hormonal mutants, we determined that ethylene or cytokinin signaling was necessary for increased plant growth in response to the VOCs emitted by strain E6818 We established that GB03 volatiles triggered ethylene- signaling as revealed from overexpression of PDF1.2.7 In contrast, volatile emission from strain E681 caused to upregulate GUS fused in PR1 promoter. This result suggests that certain VOCs emitted by strain E681 can be deemed comparable to those released from strain GB03. Surprisingly, strain E681-mediated ISR capacity was greater than in plants exposed to those emitted from strain GB03.19

Previously, an analysis of the VOCs released from three bacteria, including Paenibacillus polymxa from potato tubers, showed that dimethylformamide, pentadecene and hexadecane are unique volatiles generated by P. polymxya.20 This result is in agreement with our previous data.21 A comparison with our previous data21 revealed that hexadecane was emitted exclusively from P. polymyxa, but not from B. subtilis and B. amyloliqefaciens. The exclusive bacteria species that reported to emit hexadecane is the cyanobacterium Oscillatoria perornata.22 Although volatiles from fungi and bacteria have wildly obtained attention for protecting plants from pathogens, the plant’s response to hexadecane has not been thoroughly assessed. Hexadecane is a novel candidate signal molecule that can induce PR1 expression. How hexadecane was recognized and reacted by plants has not been intensively considered through the use of large scale gene expression techniques.

Previous study revealed a plant growth regulator cytokinin secreted by P. polymyxa played an critical role on plant growth promotion in Arabidopsis.17 In addition to cytokinin, the current results present bacterial volatiles as additional bacterial determinants, corresponding to promotion of seedling growth by P. polymyxa E681 (Fig. 1D). Moreover, the strain E681 produces hexadecane out of a blend of volatiles that trigger ISR against biotrophic pathogenic bacterium, P. syringae. Hexadecane released by strain E681 induced expression of the PR1 gene as a greater extent than those released by strain GB03.19 Our results newly indicate that strain E681produces hexadecane, which triggers an ISR response that is stronger than previous bacterial volatiles such as acetoin and 2,3-butanediol. The further greenhouse and field experiments can broaden our knowledge to apply bacterial volatiles to protect crop plant against plant pathogens.

Acknowledgments

Financial support was obtained from the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2010-0011655), the Industrial Source Technology Development Program of the Ministry of Knowledge Economy (10035386) of Korea, the Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program (SSAC grant #PJ009524), Rural Development Administration, South Korea and the KRIBB initiative program (South Korea).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- VOC

volatile organic compounds

- PGPR

plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria

- ISR

induction of systemic resistance

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/24619

References

- 1.Kloepper JW. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria as biological control agents in Metting, F.B., ed. Soil Microbial Ecology: Applications in Agricultural and Environmental Management, New York, NY: Marcel Dekker Inc, 1993: 255-274. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryu CM, Kim J, Choi O, Kim SH, Park CS. Improvement of biological control capacity of Paenibacillus polymyxa E681 by seed pelleting on sesame. Biol Control. 2006;39:282–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2006.04.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryu CM, Murphy JF, Mysore KS, Kloepper JW. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria systemically protect Arabidopsis thaliana against Cucumber mosaic virus by a salicylic acid and NPR1-independent and jasmonic acid-dependent signaling pathway. Plant J. 2004;39:381–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Loon LC, Bakker PA, Pieterse CM. Systemic resistance induced by rhizosphere bacteria. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1998;36:453–83. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.36.1.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kloepper JW, Ryu CM, Zhang S. Induced systemic resistance and promotion of plant growth by Bacillus spp. Phytopathology. 2004;94:1259–66. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2004.94.11.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Press CM, Loper JE, Kloepper JW. Role of iron in rhizobacteria-mediated induced systemic resistance of cucumber. Phytopathology. 2001;91:593–8. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2001.91.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryu CM, Farag MA, Hu CH, Reddy MS, Kloepper JW, Paré PW. Bacterial volatiles induce systemic resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:1017–26. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.026583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryu CM, Farag MA, Hu CH, Reddy MS, Wei HX, Paré PW, et al. Bacterial volatiles promote growth in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4927–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730845100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lucy M, Reed E, Glick BR. Applications of free living plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2004;86:1–25. doi: 10.1023/B:ANTO.0000024903.10757.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Kim MS, Sun Y, Dowd SE, Shi H, Paré PW. Soil bacteria confer plant salt tolerance by tissue-specific regulation of the sodium transporter HKT1. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2008;21:737–44. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-21-6-0737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho SM, Kang BR, Han SH, Anderson AJ, Park JY, Lee YH, et al. 2R,3R-butanediol, a bacterial volatile produced by Pseudomonas chlororaphis O6, is involved in induction of systemic tolerance to drought in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2008;21:1067–75. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-21-8-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han SH, Lee SJ, Moon JH, Park KH, Yang KY, Cho BH, et al. GacS-dependent production of 2R, 3R-butanediol by Pseudomonas chlororaphis O6 is a major determinant for eliciting systemic resistance against Erwinia carotovora but not against Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci in tobacco. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2006;19:924–30. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryu CH, Kim J, Choi O, Park SY, Park SH, Park CS. Nature of a root-associated Paenibacillus polymyxa from field-grown winter barley in Korea. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;15:984–91. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryu CM, Hu CH, Locy RD, Kloepper JW. Study of mechanisms for plant growth promotion elicited by rhizobacteria in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Soil. 2005;268:285–92. doi: 10.1007/s11104-004-0301-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lebuhn M, Heulin T, Hartmann A. Production of auxin and other indolic and phenolic compounds by Paenibacillus polymyxa strains isolated from different proximity to plant roots. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;22:325–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.1997.tb00384.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakashimada Y, Marwoto B, Kashiwamura T, Kakizono T, Nishio N. Enhanced 2,3-butanediol production by addition of acetic acid in Paenibacillus polymyxa. J Biosci Bioeng. 2000;90:661–4. doi: 10.1263/jbb.90.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Timmusk S, Nicander B, Granhall U, Tillberg E. Cytokinin production by Paenibacillus polymyxa. Soil Biol Biochem. 1999;31:1847–52. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(99)00113-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwon YS, Ryu CM, Lee S, Park HB, Han KS, Lee JH, et al. Proteome analysis of Arabidopsis seedlings exposed to bacterial volatiles. Planta. 2010;232:1355–70. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee B, Farag MA, Park HB, Kloepper JW, Lee SH, Ryu CM. Induced resistance by a long-chain bacterial volatile: elicitation of plant systemic defense by a C13 volatile produced by Paenibacillus polymyxa. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e48744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Lacy Costello, Evans, Ewen, Gunson, Ratcliffe, Spencer-Phillips Identification of volatiles generated by potato tubers (Solanum tuberosum CV: Maris Piper) infected by Erwinia carotovora, Bacillus polymyxa and Arthrobacter sp. Plant Pathol. 1999;48:345–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3059.1999.00357.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farag MA, Ryu CM, Sumner LW, Paré PWGC-MS. GC-MS SPME profiling of rhizobacterial volatiles reveals prospective inducers of growth promotion and induced systemic resistance in plants. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:2262–8. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tellez MR, Schrader KK, Kobaisy M. Volatile components of the cyanobacterium Oscillatoria perornata (Skuja) J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:5989–92. doi: 10.1021/jf010722p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]