Abstract

We have previously shown that acute increases in pulmonary blood flow (PBF) are limited by a compensatory increase in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) via an endothelin-1 (ET-1) dependent decrease in nitric oxide synthase (NOS) activity. The mechanisms underlying the reduction in NO signaling are unresolved. Thus, the purpose of this study was to elucidate mechanisms of this ET-1-NO interaction. Pulmonary arterial endothelial cells (PAEC) were acutely exposed to shear stress in the presence or absence of tezosentan, a combined ETA/ETB receptor antagonist. Shear increased NOx, eNOS phospho-Ser1177, and H2O2 and decreased catalase activity; tezosentan enhanced, while ET-1 attenuated all of these changes. In addition, ET-1 increased eNOS phospho-Thr495 levels. In lambs, 4h of increased PBF decreased H2O2, eNOS phospho-Ser1177, and NOX levels, and increased eNOS phospho-Thr495, phospho-catalase and catalase activity. These changes were reversed by tezosentan. PEG-catalase reversed the positive effects of tezosentan on NO signaling. In all groups, opening the shunt resulted in a rapid increase in PBF by 30min. In vehicle- and tezosentan/PEG-catalase lambs, PBF did not change further over the 4h study period. PVR fell by 30min in vehicle- and tezosentan-treated lambs, and by 60min in tezosentan/PEG-catalase-treated lambs. In vehicle- and tezosentan/PEG-catalase lambs, PVR did not change further over the 4h study period. In tezosentan-treated lambs, PBF continued to increase and LPVR to decrease over the 4h study period. We conclude that acute increases in PBF are limited by an ET-1 dependent decrease in NO production via alterations in catalase activity, H2O2 levels, and eNOS phosphorylation.

Keywords: pulmonary blood flow, nitric oxide, endothelin-1, hydrogen peroxide, catalase, eNOS, biomechanical forces

INTRODUCTION

Elevated shear stress within the pulmonary vasculature is a factor in the pathophysiology of several pulmonary hypertensive disorders (Moraes and Loscalzo, 1997). Acute increases in shear stress accompany surgically induced increases in pulmonary blood flow (PBF), such as those associated with the repair of several common congenital cardiac defects (Tworetzky et al., 2000). We have previously described a novel model of a surgically induced acute increase in PBF, created by the placement of a large (8 mm) vascular graft between the aorta and pulmonary artery in an intact juvenile lamb (Oishi et al., 2006). In this model, the acute increase in PBF was followed by compensatory pulmonary vascular constriction that was, in part, mediated by an endothelin-1 (ET-1) dependent decrease in endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity. However, the mechanisms linking increased PBF, ET receptor activation, and a decrease in NOS activity remain unclear.

A large body of evidence demonstrates that eNOS is dynamically regulated at the transcriptional- (Searles, 2006), post-transcriptional-(Searles, 2006), and post-translational levels (Fulton et al., 2001; Rafikov et al., 2011). In addition, factors such as intracellular location (Shaul, 2002), protein-protein interactions (Rafikov et al., 2011), and substrate and cofactor availability (Sharma et al., 2012) can all regulate eNOS activity. Furthermore, mechanical forces can impact eNOS. We have also shown that acute increases in fluid shear stress can increase eNOS activity in vitro, independent of changes in eNOS expression (Kumar et al., 2010). The shear-mediated increase in eNOS activity appears to be regulated, in part, by the phosphorylation status of eNOS (Kumar et al., 2010). A key phosphorylation site on eNOS is located at serine 1177 (Ser1177) (Fulton et al., 1999). Recently, we demonstrated that in pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAEC) acute increases in shear stress were accompanied by: decreased catalase activity, increased hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) production, increased eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177, and increased NO generation (Kumar et al., 2010). These findings, however, contrast the ET-1 mediated decrease in NOS activity in our lamb model of increased PBF (Oishi et al., 2006). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore the potential role of H2O2 signaling under conditions of acutely increased PBF in vivo, using our lamb model. We hypothesized that acute increases in PBF are associated with ET receptor mediated alterations in H2O2 signaling that result in decreased NOS activity and bioavailable NO. The juvenile lamb is ideally suited to mimic the cardiopulmonary physiologic changes noted in infants undergoing surgical-induced acute changes in pulmonary blood flow. Many of the fetal and neonatal pulmonary blood flow patterns have been investigated in the lamb, and have been found to mimic the physiology of humans. In addition, its size facilitates the ability to safely perform the surgical interventions needed, monitor vascular pressures and flow, and perform intermittent peripheral lung biopsies.

Our findings indicate that acute increases in PBF in lambs, results in an ET receptor mediated increase in catalase activity that decreases H2O2 levels, eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177, and bioavailable NO. These effects can be modulated by both ET receptor antagonism and augmentation of catalase activity.

MATERIAL & METHODS

Cell culture

Primary cultures of ovine PAEC were isolated as described previously (Wedgwood et al., 2001). Cells were maintained in DMEM containing phenol red supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT), antibiotics, and antimycotics (MediaTech, Herndon, VA) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2-95% air. Cells were utilized between passages 3 and 10.

Shear stress and ET-1 treatment

Laminar shear stress, in the presence and absence of tezosentan (5μM), was applied using a cone-plate viscometer that accepts six-well tissue culture plates, as described previously (Kumar et al., 2010). This method achieves laminar flow rates that represent physiological levels of laminar shear stress in the major human arteries, which is in the range of 5–20 dyn/cm2 (Laurindo et al., 1994). Confluent serum-starved PAEC (16h) were also treated with ET-1 (100nM, Sigma) and exposed or not to laminar shear stress. In certain experiments PAEC were also exposed to the ETA receptor antagonist, BQ-123 (10μM, Sigma) or the ETB receptor antagonist, Res 701-3 (10μM, American peptide, Sunnyvale, CA). The media and cells were collected and used for further experiments. PAEC were also treated with ETB receptor agonist 4-ala ET-1 (100nM, Phoenix Pharmaceutical, Burlingame, CA) for 4h.

Western blotting

Serum-starved PAEC (16h) were sheared with or without tezosentan (5μM) for 4 h and solubilized with a lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, 20 mM Tris. pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Pierce). Insoluble proteins were precipitated by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were then subjected to SDS-PAGE on 4–20% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to a Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (BioRad). The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk or 5% Bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween (TBST). The primary antibodies used for immunoblotting were anti-catalase, anti-phospho-serine (1:500; Calbiochem); anti-phospho-Ser1177 eNOS, anti-eNOS (1:1,000; BD Biosciences), ETA receptor (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and ETB receptor (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). For the studies to determine the ratios of pThr-485 eNOS or p-Ser1177 eNOS to total eNOS two separate gels were run. Membranes were then washed with TBST three times for 10 min, incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody coupled to horseradish peroxidase, washed again with TBST as described above, and the protein bands visualized with ECL reagent (Pierce) using a Kodak 440CF image station. Loading was normalized by re-probing the membranes with an anti-β-actin antibody (1:2,500; Sigma).

Determination of catalase activity

Catalase activity was measured as described (Kumar et al., 2010). This method is based on the rate of degradation of H2O2 to form water and oxygen over time. In both cell and ovine lung studies, total protein extracts (40μg) were diluted to 1ml in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). One milliliter of 10 mM H2O2 solution was added, and the decomposition of the substrate was recorded by the decrease in absorbance at 240 nm over a 60s period. Catalase activity was expressed as degradation of H2O2·mg protein−1·min−1.

Detection of NOx

NO generated by PAEC in response to shear was measured in the media using a NO-sensitive electrode with a 2-mm diameter tip (ISO-NOP sensor, WPI) connected to a NO meter (ISO-NO Mark II, WPI) as described previously (Kumar et al., 2010). NO levels in the lung lysate were determined by indirect method of measuring the levels of nitrite as we have previously described (McMullan et al., 2000). Briefly, samples were deproteinized by adding cold ethanol to the sample (1:4 v:v) and then concentrated using a speed-vac. Potassium iodide/acetic acid reagent was prepared fresh daily. This reagent was added to a septum sealed purge vessel and bubbled with nitrogen gas. The gas stream was connected via a trap containing 1N NaOH, to a Sievers 280i Nitric Oxide Analyzer (GE). Deproteinized samples were injected with a syringe through a silicone/Teflon septum. Results were analyzed by measuring the area under curve of the chemiluminescence signal using the Liquid software (GE).

Measurement of H2O2 levels

A modified H2DCFDA oxidation method was used to detect H2O2 levels (Wedgwood and Black, 2005). For the cell culture studies H2O2 levels were detected in the media. For the lambs studies snap-frozen peripherial lung tissue samples stored at −80°C were powdered. Powdered tissue samples (20mg) were homogenized in PBS (100μl) and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10min at 4°C. The supernatant was then used for detection of H2O2 levels. Fifty microliters of culture media or lung lysate were incubated with H2DCFDA (25μM, Calbiochem) for 30 min in the dark with or without 100 U/ml catalase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Purified catalase was used to confirm that the oxidation of H2DCFDA was H2O2 dependent. The samples were measured with excitation at 485nm and emission at 530nm in Fluoroskan Ascent FL (Thermo Electron, Waltham, MA). Oxidation of H2DCFDA was converted into μmols of H2O2 by using a standard curve prepared from the oxidation of known concentration of H2O2 as we published previously 13.

Immunoprecipitation to detect phospho-catalase

For each immunoprecipitation, 1000μg of lung lysate was incubated with an anti-catalase antibody overnight at 4°C followed by incubation with a protein G Plus/Protein A agarose suspension (Calbiochem) for 1h at 4°C. The immune complexes were washed three times with lysis buffer and boiled in SDS-PAGE sample buffer for 5 min. Agarose beads were pelleted by centrifugation, and the protein supernatants were loaded and run on 4–20% polyacrylamide gels, followed by transfer of the proteins to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with 2% BSA in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST) for 2 h at room temperature, incubated with anti-phosphoserine antibody (Calbiochem) overnight at 4°C, washed three times with TBST (room temperature, 10 min), and then incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Pierce). The reactive bands were visualized with the SuperSignal West Femto maximum sensitivity substrate kit (Pierce) using a Kodak 440CF image station. The same blot was reprobed with anti-catalase antibody to normalize for the levels of catalase immunoprecipitated in each sample.

Lamb model of surgically induced acute increases in PBF

Fifteen juvenile lambs (4-6 weeks of age) were fasted for 24h, with free access to water. The lambs were then anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (15mg/kg IM). Under additional local anesthesia with 2% lidocaine hydrochloride, polyurethane catheters were placed in an artery and vein of each hind leg. These catheters were advanced to the descending aorta and the inferior vena cava, respectively. The lambs were then anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (~0.3mg/kg/min), diazepam (0.002mg/kg/min), and fentanyl citrate (1.0μg/kg/hr), intubated with a 7.0mm OD cuffed endotracheal tube, and mechanically ventilated with a V.I.P Bird® Sterling (Palm Springs, CA) time-cycled, pressure-limited ventilator. Pancuronium bromide (0.1mg/kg/dose) was given intermittently for muscle relaxation. Utilizing strict aseptic technique, a midsternotomy incision was then performed, and the pericardium was incised. With the use of side biting vascular clamps, an 8.0mm Gore-tex® vascular graft (~2mm length) (W.L. Gore and Associates, Milpitas, CA), which was occluded by vascular clips, was anastomosed between the ascending aorta and main pulmonary artery with 7.0 proline (Ethicon Inc., Somerville, NJ), using a continuous suture technique. Utilizing a purse-string suture technique, polyurethane catheters were placed directly into the right and left atrium, and main pulmonary artery. An ultrasonic flow probe (Transonics Systems, Ithaca, NY) was placed around the left pulmonary artery to measure pulmonary blood flow. The midsternotomy incision was then temporarily closed with towel clamps. An intravenous infusion of Lactated Ringers and 5% Dextrose (75ml/h) was begun and continued throughout the study period. Cefazolin (500mg, IV) and gentamicin (3mg/kg, IV) were administered before the first surgical incision. The lambs were maintained normothermic (39°C) with a heating blanket.

Experimental Protocol

After a 30min recovery, baseline measurements of the hemodynamic variables (pulmonary and systemic arterial pressure, heart rate, left pulmonary blood flow, left and right atrial pressures), and systemic arterial blood gases and pH were measured. A peripheral lung wedge biopsy was obtained for determinations of: H2O2 levels, catalase expression and activity, phospho-catalase levels, eNOS phosphorylation at Thr495 and Ser1177, and NOX levels. A side-biting vascular clamp was utilized to isolate peripheral lung tissue from a randomly selected lobe, and the incision was cauterized. Approximately 300mg of peripheral lung were obtained for each biopsy.

In control lambs (N=5) an infusion of normal saline (vehicle) was initiated and continued throughout the study period. In a second group (N=5), an infusion of tezosentan (a combined ETA and ETB receptor antagonist) was initiated at 0.5mg/kg/hour and continued throughout the study period. The dose of tezosentan was determined from previous work that demonstrates physiologically significant blockade of ET-1 induced vascular alterations (Fitzgerald et al., 2004). In a third group (N=5), an intravenous dose of PEG-catalase (15,000 units/kg) was administered before the initiation of the tezosentan infusion. Tezosentan (0.5mg/kg/hour) was then administered throughout the study period. The dose of PEG-catalase (15,000 units/kg) was based on studies that demonstrated significant (nine-fold) sustained increases in plasma catalase activity (Carpenter et al., 2001). In our initial study describing this model, we showed that a sham procedure (which was identical to the procedure above except that the surgical clips were not removed from the vascular graft) did not produce any appreciable hemodynamic or biochemical alterations (Oishi et al., 2006).

One hour following the initiation of the infusion (vehicle, tezosentan, or tezosentan plus PEG-catalase), the vascular clips were removed from the aortopulmonary graft, opening the shunt. Hemodynamic variables were monitored continuously for 4h. Four hours following shunt opening, a lung biopsy was obtained for determinations of: H2O2 levels, catalase expression and activity, phospho-catalase levels, eNOS phosphorylation at Thr495 and Ser1177, and NOX levels.

At the end of the protocol, all lambs were killed with a lethal injection of sodium pentobarbital followed by bilateral thoracotomy as described in the NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All protocols and procedures were approved by the Committee on Animal Research of the University of California, San Francisco and Georgia Health Sciences University.

Drug Preparation

Tezosentan (molecular weight 649.6, Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Allschwil, Switzerland) was diluted in sterile 0.9% saline to a final concentration of 1mg/ml and used immediately. Polyethylene glycol-conjugated catalase (2000-5000 units/mg protein, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was diluted in 5ml sterile 0.9% saline and used immediately.

Measurements

Pulmonary and systemic arterial, and right and left atrial pressures were measured using Sorenson Neonatal Transducers (Abbott Critical Care Systems, N. Chicago, IL). Mean pressures were obtained by electrical integration. Heart rate was measured by a cardiotachometer triggered from the phasic systemic arterial pressure pulse wave. Left pulmonary blood flow was measured on an ultrasonic flow meter (Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY). All hemodynamic variables were measured continuously utilizing the Gould Ponemah Physiology Platform (Version 4.2) and Acquisition Interface (Model ACG-16, Gould Inc., Cleveland, OH), and recorded with a Dell Inspiron 5160 computer (Dell Inc., Round Rock, TX). Blood gases and pH were measured on a Radiometer ABL5 pH/blood gas analyzer (Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark). Hemoglobin concentration and oxygen saturation were measured by a co-oximeter (model 682, Instrumentation Laboratory, Lexington, MA). Pulmonary vascular resistance was calculated using standard formulas. Body temperature was monitored continuously with a rectal temperature probe.

Statistical analysis

Statistical calculations were performed using the GraphPad Prism V. 4.01 software. The means ± SE was calculated for all samples, and significance was determined by either the unpaired or paired t-test or ANOVA. For ANOVA, Newman-Keuls post hoc testing was also utilized. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

ET receptor antagonism enhances shear-mediated increases in NO generation in pulmonary arterial endothelial cells

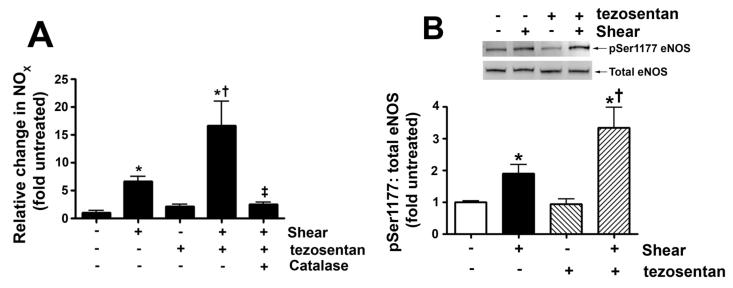

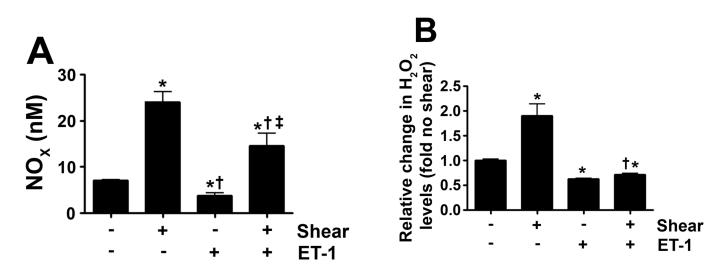

Our previous in vivo study indicated that increased PBF combined with tezosentan treatment resulted in an increase in NOS activity (REF). Therefore, our first step was to determine NOX concentrations in the media of PAEC exposed to acute shear stress (20 dyn/cm2, 4h) in the presence and absence of tezosentan. As expected, NOX levels were significantly increased in response to shear stress (Fig. 1 A). Tezosentan potentiated the shear mediated increase in NOX (Fig. 1 A).

Figure 1. ET receptor antagonism enhances shear-mediated increases in NO generation in pulmonary arterial endothelial cells.

PAEC were acutely exposed to shear stress (20 dyn/cm2, 4 h) in the presence or absence of the combined ET receptor antagonist, tezosentan (5μM). Shear mediated increase in NO generation were potentiated in the presence of tezosentan (A). The increase in NO correlated with an increase in the ratio of pSer1177 eNOS vs. total eNOS (B) in both shear and shear with tezosentan. The increases in NO generation are attenuated by PEG-catalase (100U/ml; A). Data are mean± SEM; n =4-6. *P<0.05 vs. no shear, †P <0.05 vs. shear alone, ‡P<0.05 vs. shear and tezosentan.

ET receptor antagonism increases shear-mediated phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser1177 in pulmonary arterial endothelial cells

In order to investigate potential mechanisms for the ET receptor mediated increase in NO generation with acute shear stress in PAEC we performed Western blot analysis to measure phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser1177, a site known to increase eNOS activity. Again PAEC were exposed to acute shear stress (20 dyn/cm2, 4h) in the presence and absence of tezosentan. Consistent with our previous studies (Kumar et al., 2010), we found that acute shear stress significantly increased pSer1177 eNOS levels (Fig. 1 B). While, in the presence of tezosentan, the increase in pSer1177 eNOS induced by shear stress was potentiated (Fig. 1 B).

ET receptor antagonism enhances shear-mediated increases in H2O2 generation in pulmonary arterial endothelial cells

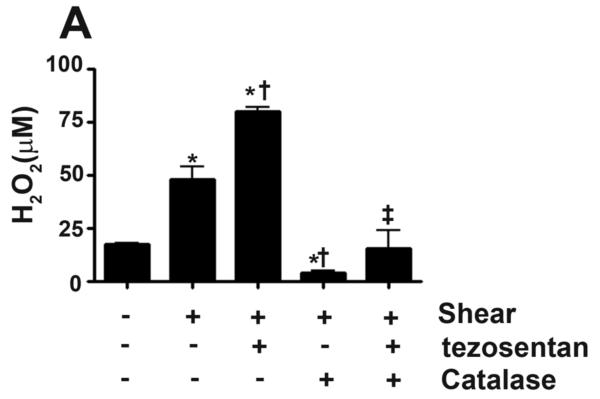

Our previous studies have shown that shear stress increases Ser1177 eNOS in PAEC via Akt activation secondary to increased H2O2 generation (Kumar et al., 2010). Therefore, we next measured cellular H2O2 levels, as estimated by H2DCFDA oxidation, in PAEC exposed to acute shear stress (20 dyn/cm2, 4h) in the presence and absence of tezosentan. Consistent with our previous studies, our results indicated that cellular H2O2 levels were significantly increased in response to shear (Fig. 2 A). While in the presence of tezosentan, the cellular H2O2 levels induced by shear stress was potentiated (Fig. 2 A). The addition of catalase decreased the signal under both conditions, indicating specificity of the assay for H2O2 (Fig. 2 A). Confirming the important role of H2O2, the addition of catalase attenuated the shear and tezosentan mediated increases in NOX (Fig. 1 A).

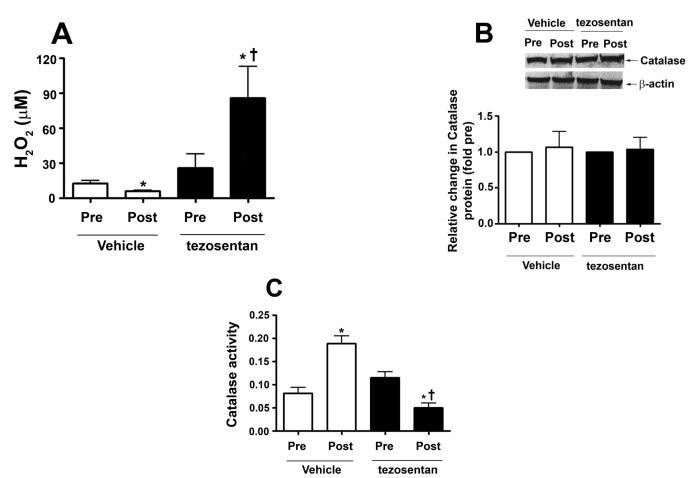

Figure 2. ET receptor antagonism potentiates shear-mediated increase in H2O2 via a decrease in catalase activity.

PAEC were acutely exposed to shear stress (20 dyn/cm2, 4 h) in the presence or absence of the combined ET receptor antagonist, tezosentan (5μM). The levels of H2O2 were determined in the media by H2DCFDA oxidation reaction and whole cell extracts (20μg) were subjected to Western blot analysis in order to determine changes in catalase protein levels. Catalase activity (H2O2 degraded/min/mg protein) was also determined. The shear mediated increase in H2O2 was enhanced by tezosentan (A) and attenuated by PEG-catalase (100U/ml, A). Neither shear nor tezosentan changed catalase protein levels (B). However, acute shear stress decreased catalase activity, which was further attenuated by tezosentan (C). Data are mean± SEM; n =3-6. *P <0.05 vs. no shear, †P <0.05 vs. shear alone, ‡P<0.05 vs. shear and tezosentan.

ET receptor antagonism potentiates a shear-mediated decrease in catalase activity in pulmonary arterial endothelial cells

We have previously shown that shear stress decreases catalase activity in PAEC (Kumar et al., 2010). Therefore, we determined catalase expression and activity in PAEC exposed to acute shear stress (20 dyn/cm2, 4h) in the presence and absence of tezosentan. Consistent with our previous studies, our results indicated that catalase protein levels did not change in response to shear (Fig. 2 B), but catalase activity was significantly decreased (Fig. 2 C). In the presence of tezosentan, there was a further significant reduction in catalase activity in PAEC exposed to shear stress (Fig. 2 C). Tezosentan had no affect on catalase protein levels (Fig. 2 B).

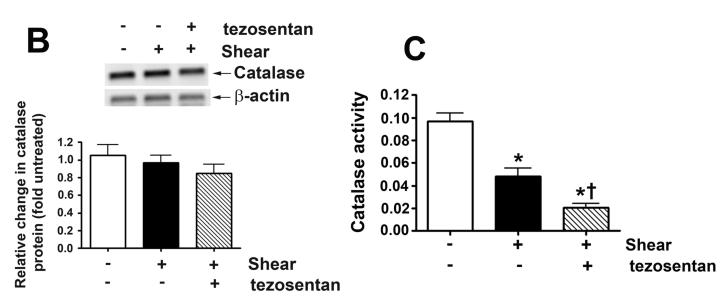

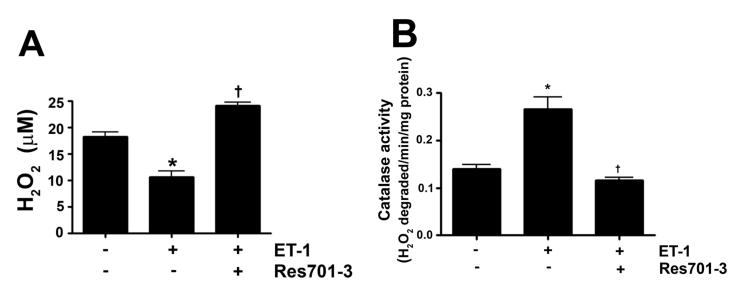

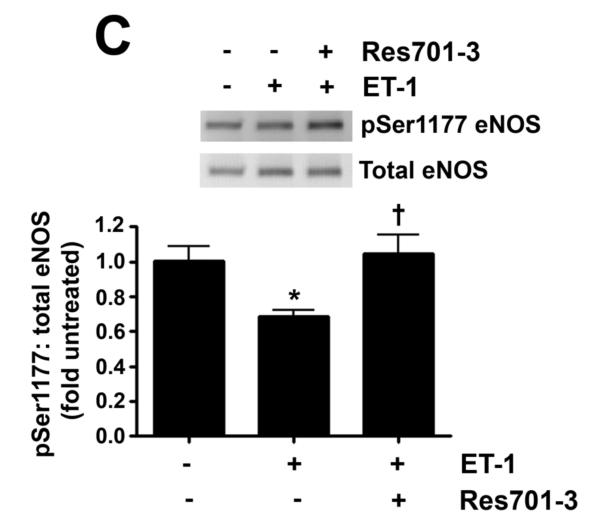

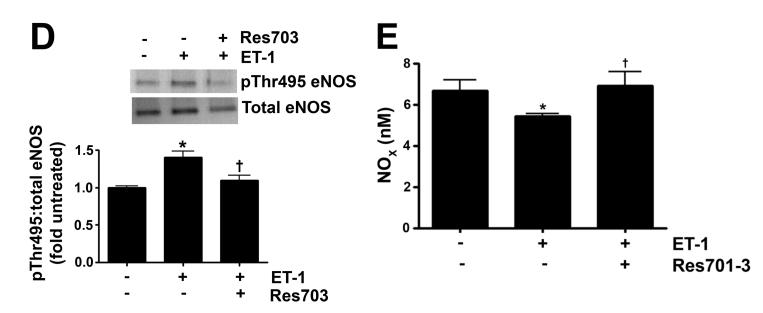

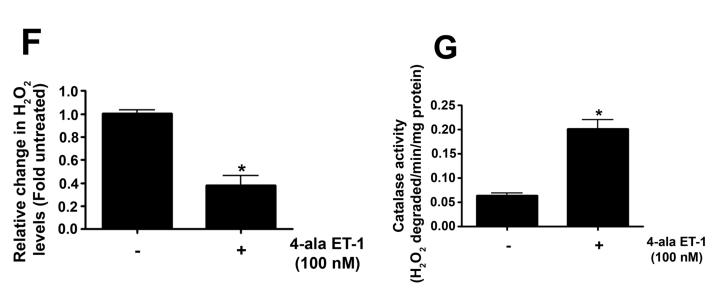

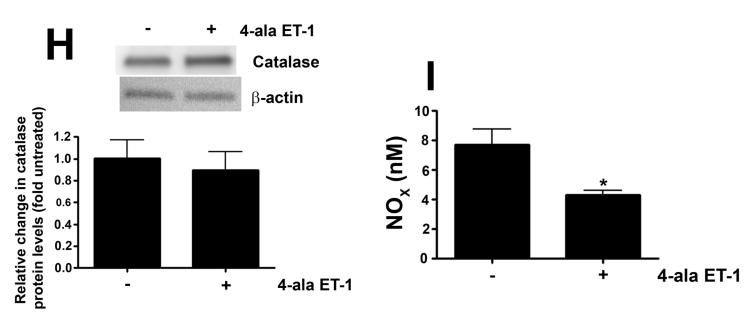

ET-1 decreases NO signaling in pulmonary arterial endothelial cells by increasing catalase activity

As we have previously shown that ET-1 decreases in NOS activity in our lamb model of acutely increased PBF (Oishi et al., 2006) we next determined if this was due to modulation of pSer1177 or pThr495 eNOS levels and the role of ETB receptor signaling. Our data indicate that ET-1 significantly decreased H2O2 levels in PAEC (Fig. 3 A). This decrease in H2O2 correlated with a significant increase in catalase activity (Fig. 3 B). The decrease in H2O2 correlated with a significant decrease in p-Ser1177 eNOS (Fig. 3 C) and a significant increase in pThr495 eNOS (Fig. 3 D). Overall these changes resulted in a significant decrease in NOx levels (Fig. 3 E). The addition of the ETB-receptor antagonist, Res701-3 blocked all these changes (Fig. 3 A-D). To further confirm the role of ETB receptor activation in the reduction in NO signaling we exposed PAEC to the ETB receptor specific agonist, 4-ala ET-1. We found that 4-ala ET-1 significantly decreased both H2O2 levels (Fig. 3 F) and catalase activity (untreated, Fig. 3 G) without altering catalase protein levels (Fig. 3 H). 4-ala ET-1 also significantly decreased NOx levels (Fig. 3 I).

Figure 3. ET-1 treatment decreases H2O2 levels and NO generation via ETB receptor signaling.

PAEC were exposed to ET-1 (100nM, 4h) in the presence or absence of the ETB receptor antagonist Res701-3 (10μM). The media was used for the measurement of H2O2 and NO levels. The cell lysate was then used for determination of the pSer1177- and pThr495-eNOS, total eNOS, catalase activity and catalase protein levels. ET-1 decreased H2O2 levels (A), and increased catalase activity (B, H2O2 degraded/min/mg protein). ET-1 also decreased pSer1177 eNOS levels (C) but increased the level of pThr495 eNOS (D) as determined by Western blot analysis. NO generation was also decreased with ET-1 treatment (E). The ETB receptor antagonist, Res701-3 blocked all of these effects (A-E). PAEC were also treated with the ETB receptor agonist, 4-ala ET-1 (100nM, 4h). H2O2 levels decreased with 4-ala ET-1 treatment (F) while catalase activity (H2O2 degraded/min/mg protein) increased (G). Catalase protein levels did not change (H). NO levels were also decreased by 4-ala ET-1 (I). Data are mean± SEM; n =4-6. *P <0.05 vs. untreated, †P <0.05 vs. ET-1 alone.

ET-1 attenuates the shear mediated increase in H2O2 and NO generation in pulmonary arterial endothelial cells by increasing catalase activity

In our lamb model of acute increases in PBF there is both increased shear stress and ET-1 levels (Oishi et al., 2006). Thus, we next determined the affect on H2O2 and NO signaling if we exposed PAEC to shear stress in the presence of ET-1. Our data indicate that ET-1 significantly reduced both the shear mediated increases in NOx (Fig. 4 A) and H2O2 (Fig. 4 B) indicating that ET-1 is dominant over shear stress with respect to NO and H2O2 generation.

Figure 4. ET-1 attenuates shear-mediated increase in NO generation and H2O2 levels in pulmonary arterial endothelial cells.

PAEC were acutely exposed to shear stress (20 dyn/cm2, 4 h) in the presence or absence of ET-1 (100nM, 4h) and the media used for the detection of H2O2 and NOx. The shear mediated increase in NOx (A) and H2O2 (B) were attenuated in the presence of ET-1. Data are mean± SEM; n =6-12. *P <0.05 vs. no shear, †P <0.05 vs. shear alone, ‡P<0.05 vs. ET-1 alone.

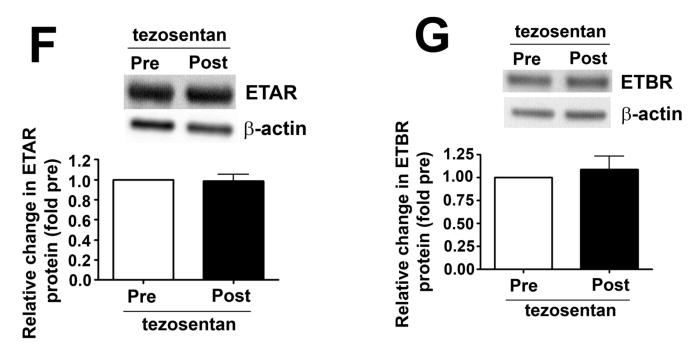

In lambs, exposure to acute increases in pulmonary blood flow decreases lung tissue H2O2 levels, which is reversed by ET receptor antagonism

H2O2 levels, estimated by H2DCFDA oxidation, were determined in peripheral lung biopsies taken before (pre) and 4h after (post) shunt opening in lambs in the absence (vehicle-treated) and presence of tezosentan. In vehicle-treated lambs, lung tissue H2O2 levels are significantly decreased after 4h of increased PBF (Fig. 5 A). However, in tezosentan-treated lambs, lung tissue H2O2 levels were significantly increased (Fig. 5 A).

Figure 5. ET receptor antagonism increases lung tissue H2O2 levels, in association with attenuated catalase activity, in lambs acutely exposed to increased pulmonary blood flow.

Lung biopsies were taken before (Pre) and 4h after (Post) the increase in PBF. In vehicle-treated lambs, H2O2 levels, as estimated by H2DCFDA oxidation, decreased after 4h of increased PBF; whereas, in tezosentan-treated lambs, H2O2 levels increased (A). Western blot analysis performed on lysates (20μg) prepared from Pre and Post lung biopsies, revealed no change in catalase protein after 4h of increased PBF, in either vehicle- or tezosentan-treated lambs (B). However, in vehicle-treated lambs, lung tissue catalase activity was enhanced after 4h of PBF; whereas, in tezosentan-treated lambs catalase activity decreased (C). Lung lysate (1 mg) were also subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP), using an antibody specific to catalase followed by Western blot (IB) analysis using a specific antiserum raised against phosphorylated-serine residues. In vehicle-treated lambs, the increase in catalase activity was associated with an increase in phospho-serine catalase (pSercatalase), whereas, in tezosentan treated lambs pSer-catalase levels were decreased (D). Data are mean ± SEM; n =5-7. *P <0.05 vs. pre shunt opening, †P <0.05 vs. vehicle-treated post.

In lambs, exposure to acute elevations in pulmonary blood flow increases lung tissue catalase activity, independent of protein expression, which is reversed by ET receptor antagonism

In order to further explore potential mechanisms for these in vivo differences in H2O2 levels, we measured catalase protein levels and activity in peripheral lung biopsies taken before and 4h hours after shunt opening in lambs treated or not with tezosentan. We did not find differences in catalase protein levels post shunt opening in either group (Fig. 5 B). However, in vehicle-treated lambs, lung catalase activity was significantly increased 4h after shunt opening (Fig. 5 C). In contrast, in tezosentan-treated lambs, lung tissue catalase activity was significantly decreased 4h after shunt opening (Fig. 5 C). These data are consistent with altered catalase activity contributing to the in vivo differences in H2O2 levels with and without tezosentan.

In lambs, exposure to acute elevations in pulmonary blood flow increases lung tissue p-Ser catalase serine levels

Our previous in vitro studies indicated that shear stress induced decreases in catalase activity were associated with a decrease in catalase serine phosphorylation (Kumar et al., 2010). Therefore, in order to determine whether a similar mechanism occurs in vivo, we measured pSer-catalase levels in peripheral lung biopsies taken before and 4h after shunt opening. We found that lung tissue pSer-catalase levels were significantly increased 4h after shunt opening (Fig. 5 D) while in the presence of tezosentan, pSercatalase levels were significantly decreased (Fig. 5 D).

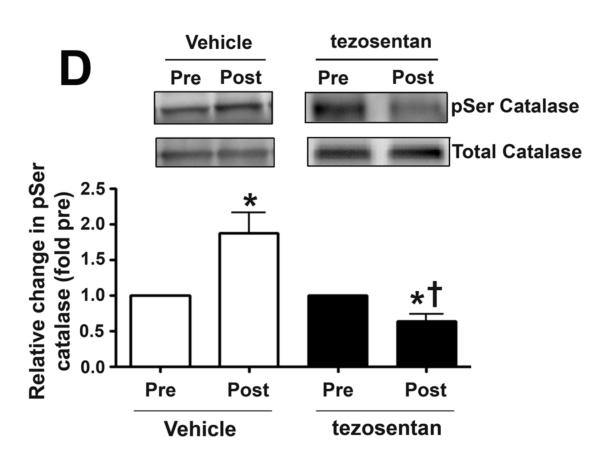

In lambs, exposure to acute elevations in pulmonary blood flow modulates eNOS phosphorylation and decreases bioavailable NO

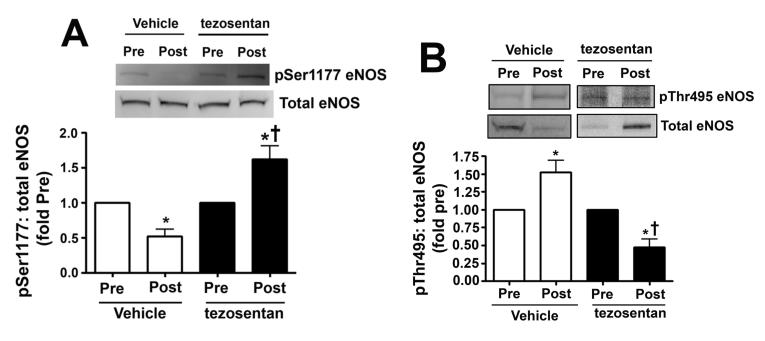

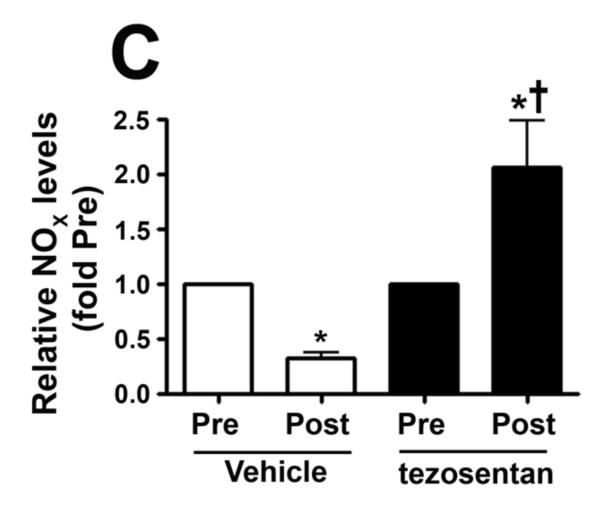

We measured eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177 and Thr495 in peripheral lung biopsies taken before and 4h after shunt opening in lambs treated or not with tezosentan. In vehicle-treated lambs, pSer1177 eNOS was significantly decreased (Fig. 6 A) while pThr495 eNOS levels significantly increased (Fig. 6 B) 4h after shunt opening. However, in tezosentan-treated lambs, pSer1177 eNOS was significantly increased (Fig. 6 A) while pThr495 eNOS significantly decreased (Fig. 6 B) 4h after shunt opening. Further, NOx levels significantly decreased 4h after shunt opening in vehicle-treated lambs but significantly increased in tezosentan-treated lambs (Fig. 6 C). The changes were not due to changes in ET receptor density, as ETA- or ETB-receptor protein levels were not altered (Fig. 6 D-G).

Figure 6. ET receptor antagonism increases p-Ser1177 eNOS levels and NO in lambs acutely exposed to increased pulmonary blood flow.

PBF was acutely increased in 4-week old lambs in the absence (vehicle-treated) or presence of the ET receptor antagonist tezosentan (0.5mg/kg/hr). Lung biopsies were taken before (Pre) and 4h after (Post), the increase in PBF. Lysates (40μg) prepared from these samples were subjected to Western blot analysis and probed with anti-pSer1177- or anti-pThr495-eNOS antibodies. For normalization, duplicate samples were run and blotted, then probed with an antibody for total eNOS. In vehicle-treated lambs, pSer1177 eNOS levels decreased after 4h of increased PBF; whereas, in tezosentan-treated lambs pSer1177 eNOS levels increased (A). In vehicle-treated lambs, pThr495 eNOS levels increased after 4h of increased PBF; whereas, in tezosentan-treated lambs pThr495 eNOS levels decreased (B). The changes in phosphorylation corresponded with a reduction in NOx levels after 4h of increased PBF in vehicle-treated lambs, but an increase in NOX levels in tezosentan-treated lambs (C). No changes in either ETA or ETB receptor protein levels were observed (D-G). Data are mean ± SEM; n =4-5. *P <0.05 vs. pre shunt opening, †P<0.05 vs. vehicle-treated post.

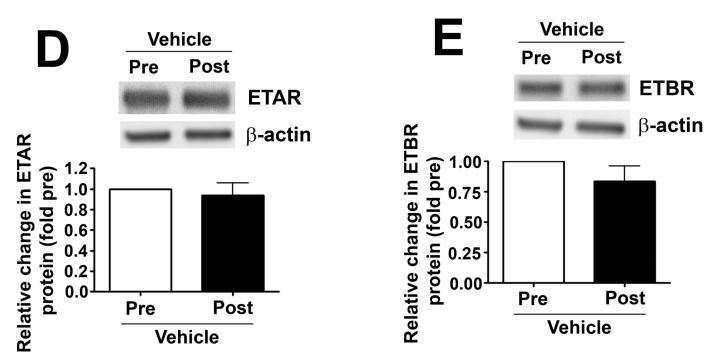

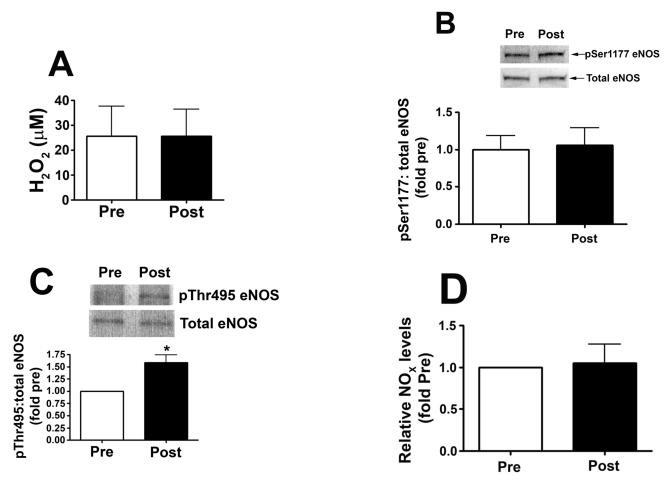

PEG-Catalase attenuates the effects of ET receptor antagonism in lambs exposed to increased pulmonary blood flow

Our results indicated that alterations in H2O2 were central to the augmentation of bioavailable NO in tezosentan-treated lambs exposed to increased PBF. In order to further examine this association, PEG-catalase was administered to an additional group of tezosentan-treated lambs exposed to increased PBF. In contrast to lambs treated with tezosentan-alone, we found no differences in lung tissue H2O2 levels, as estimated by H2DCFDA oxidation (Fig. 7 A), pSer1177 eNOS (Fig. 7 B), or NOX levels (Fig. 7 D) in lambs treated with PEG-catalase in combination with tezosentan during 4h of increased PBF. However, pThr495 eNOS levels were significantly increased (Fig. 7 C).

Figure 7. PEG-conjugated catalase attenuates the beneficial effect of ET receptor antagonism on NO signaling in lambs acutely exposed to increased pulmonary blood flow.

PBF was acutely increased in 4-week old lambs. Lambs were treated with the ET receptor antagonist tezosentan (0.5 mg/kg/hr) in combination with PEG-catalase (15,000 units/kg). Lung biopsies were taken before (Pre) and 4h after (Post), the increase in PBF. In contrast to the findings in tezosentan-treated lambs, lambs treated with tezosentan in combination with PEG-catalase, did not demonstrate increases in lung tissue H2O2 levels, as estimated by H2DCFDA oxidation, after 4h of increased PBF (A). Lysates (40μg) prepared from Pre and Post lung biopsies were subjected to Western blot analysis and probed with anti-pSer1177- or anti-pThr495-eNOS antibodies. For normalization, duplicate samples were run and blotted, then probed with an antibody for total eNOS. In contrast to the findings in tezosentan-treated lambs, lambs treated with tezosentan in combination with PEG-catalase, did not demonstrate increases in pSer1177 eNOS levels after 4h of increased PBF (B) while pThr495 levels were increased (C). Lung tissue NOX levels did not increase in lambs treated with tezosentan in combination with PEG-catalase (D). Data are mean ± SEM; n =4. *P <0.05 vs. pre shunt opening.

The co-administration of PEG-catalase and tezosentan restores compensatory pulmonary vascular constriction

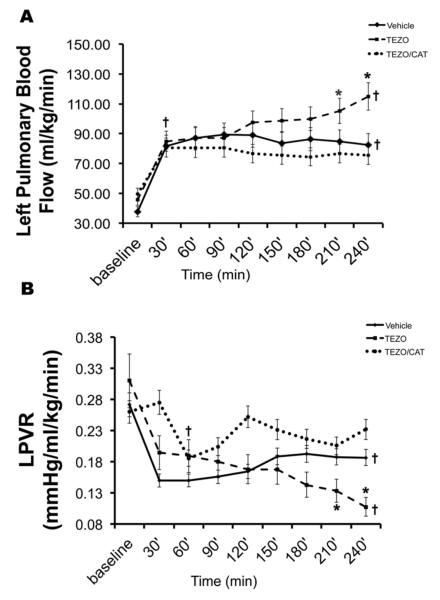

In order to investigate the physiologic relevance of these biochemical alterations in vivo, we studied the hemodynamic effects of the co-administration of PEG-catalase and tezosentan, compared to tezosentan alone or the vehicle control in our lamb model of surgically induced acutely increased PBF (Oishi et al., 2006). As expected, and consistent with our previous study (Oishi et al., 2006), in vehicle-treated lambs, opening of the aortopulmonary vascular graft resulted in a rapid and significant increase in PBF (from 38.6 ± 15.4 to 84.7 ± 20.0ml·min−1·kg−1 at 30min) and a significant decrease in left PVR (LPVR; from 0.29 ± 0.16 to 0.15 ± 0.05mmHg·ml−1·min·kg at 30min), which did not change further over the subsequent 4h study period (Fig. 8 A & B). Also consistent with our previous study, in tezosentan-treated lambs, opening of the vascular graft resulted in a rapid and significant increase in PBF (from 41.33 ± 14.24 to 82.72.4 ± 25.41ml·min−1·kg−1 at 30min) and a significant decrease in LPVR (from 0.31 ± 0.15 to 0.18 ± 0.08mmHg·ml−1·min·kg at 30min). However, unlike vehicle-treated lambs, PBF and LPVR did not reach a plateau but rather continued to change from 30 min to 4 h after shunt opening (Fig. 8 A & B). Furthermore, by 150min PBF was significantly higher than in vehicle-treated lambs; likewise, by 180min LPVR was significantly lower than in vehicle-treated lambs (Fig. 8 A & B). Thus, our results indicated that acute increases in PBF were followed by compensatory pulmonary vascular constriction that limited progressive increases in PBF and decreases in PVR in vehicle-treated lambs and that were attenuated by ET receptor antagonism.

Figure 8. The co-administration of PEG-catalase and tezosentan restores compensatory pulmonary vascular constriction that is impaired by tezosentan alone, in lambs with acutely increased PBF.

Left pulmonary blood flow (PBF) and left pulmonary vascular resistance (LPVR) following aortopulmonary shunt opening in vehicle-, tezosentan- 0.5mg/kg/hr, TEZO), and tezosentan (0.5 mg/kg/hr) combined with PEG-catalase- (15,000 units/kg) treated lambs (TEZO/CAT). (A) PBF increases sharply by 30 minutes following aortopulmonary shunt opening in all groups. PBF continues to increase in the TEZO group (dashed line), but not in the vehicle- (solid line) or TEZO/CAT (dotted line) groups over the 4h study period; PBF is higher in the TEZO group than the other groups at 210 and 240 minutes. PBF remains above baseline in all groups at 240 minutes. (B) LPVR decreases sharply by 30 minutes following aortopulmonary shunt opening in the vehicle- (solid line) and TEZO (dashed line) groups. In the vehicle group, LPVR does not change further over the 4-hour study period. In the TEZO/CAT (dotted line) group, LPVR decreases to levels similar to the other groups by 60 minutes. Furthermore, in the TEZ/CAT group LPVR returns to levels similar to baseline by 120 minutes without further changes over the 4-hour study period. In the TEZO group, LPVR continues to decrease following aortopulmonary shunt opening over the 4-hour study period, such that LPVR is lower than in the vehicle and TEZO/CAT groups at 210 and 240 minutes. Data are mean ± SD. Vehicle N=8, TEZO N=6, TEZO/CAT N=5, * P<0.05 vs. vehicle and TEZO/CAT, † P<0.05 vs. baseline.

In lambs treated with PEG-catalase in combination with tezosentan (0.5 mg/kg/hr), opening of the aortopulmonary vascular graft also resulted in a rapid and significant increase in PBF (from 49.5 ± 17.7 to 80.6± 27.6ml·min−1·kg−1 at 30min). Interestingly, however, LPVR did not decrease immediately (LPVR; 0.26 ± 0.10 to 0.27 ± 0.17mmHg·ml−1·min·kg at 30 min), but did significantly decrease by 60min after shunt opening (LPVR; 0.19 ± 0.04mmHg·ml−1·min·kg). Like vehicle-treated, and in contrast to tezosentan alone, PBF and LPVR did not change further over the 4h study period in lambs treated with PEG-catalase in combination with tezosentan (Fig. 8 A & B).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study reveal novel interactions between ET receptor activation, H2O2 signaling, and NO production under conditions of increased PBF. In our original study establishing the model of acute surgically induced increased PBF, we found that PBF was limited by compensatory pulmonary vascular constriction mediated, in part, by increased ET-1 levels and ET receptor activation that decreased NOS activity (Oishi et al., 2006). This study elucidates the mechanisms for these interactions. Specifically, our data indicate that increased PBF, via increased ET receptor activation, increases catalase activity, due to increased catalase phosphorylation, which in turn decreases H2O2 levels. Decreased H2O2 signaling is associated with a decrease in eNOS activation and decreased NO production. A central role for ET receptor activation is demonstrated by the reversal of this sequence with ET receptor antagonism. Furthermore, a role for H2O2 signaling is demonstrated by the attenuation of the effects of ET receptor antagonism with catalase supplementation.

It is well established that laminar shear stress is an important stimulus for NO production by endothelial cells. However, the controlling mechanisms are complex and incompletely understood. A number of studies have shown that eNOS activity is regulated in a reciprocal fashion by phosphorylation at Thr495 and Ser1177, with phosphorylation of Thr495 inhibiting- (Fleming et al., 2001) and Ser1177- stimulating (Dimmeler et al., 1999) the enzyme. Thus, in a situation where ET-1 levels are high, pThr495 will predominate and NO generation in the lung will be attenuated, vasoconstriction will occur and this will result in an increase in PVR. Conversely, when pSer117 levels are high NO signaling will be enhanced, which will result in pulmonary vasodilation and a reduction in PVR. Acutely, the overall balance between pThr495 and pSer1177 will determine how much NO is generated in the lung and thus whether the pulmonary vessels are maintained in a relaxed or constricted state. Further, if this phosphorylation imbalance is maintained, and as NO is an inhibitor of SMC proliferation (Mooradian et al., 1995), this would lead to the development of endothelial dysfunction, vascular remodeling and ultimately, the development of pulmonary hypertension. Indeed in our previous studies in the lamb, in which there has been chronic attenuation of NO signaling over several days to weeks, we have observed both endothelial dysfunction and vascular remodeling (Fratz et al., 2011). The signaling pathways leading to the phosphorylation of eNOS at Th495 and S117 have been partially elucidated, indicating that phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K) (Thomas et al., 2002), protein kinase C (PKC) (Michell et al., 2001), protein kinase B (Akt) (Fulton et al., 1999), and H2O2 (Kumar et al., 2010) play important roles. Here we show here that the addition of tezosentan, a combined ETA/ETB receptor antagonist, enhanced NO signaling through increases in H2O2 and phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser1177. The increases in H2O2 were mediated by decreases in catalase activity. Conversely, in PAEC exposed to ET-1 alone or in combination with shear stress, catalase activity was increased, H2O2 levels were decreased and pSer1177 eNOS and NOx levels were attenuated while pThr495 eNOS levels were enhanced. Thus, it appears that in PAEC, ET-1 signaling is dominant and tempers shear-induced NO production. This is particularly interesting given our earlier findings in which lambs with increased PBF had increased levels of ET-1 and decreased eNOS activity, and our more recent findings in PAEC showing that over expression of preproET-1 cDNA decreased eNOS expression, at least in part, due to increased PKCδ signaling (Sud and Black, 2009). We have also shown that over-expression of PKCδ increases catalase activity and attenuates the shear-mediated increases in H2O2 and pSer1177 eNOS levels (Kumar et al., 2010). The present in vivo findings are in agreement with these in vitro data. We found that after 4h of increased PBF in lambs, catalase activity increased, in association with catalase phosphorylation, and H2O2 levels decreased. However, increased PBF in combination with ET receptor antagonism had the opposite effect on catalase activity and H2O2 levels.

At the same time, it is important to recognize differences between the in vitro and in vivo situations. In PAEC, we demonstrated shear-mediated increases in NOX production that were enhanced by ET receptor antagonism; whereas, in lambs increased PBF decreased NOX production, which was reversed by ET receptor antagonism. Although PAEC produce ET-1, a 21 amino acid polypeptide, the effects of ET-1 are mediated by at least two receptor populations, ETA and ETB. The ETA receptors are located on smooth muscle cells and mediate vasoconstriction, whereas the ETB receptors are located on endothelial cells and mediate vasodilation (Arai et al., 1990; Sakurai et al., 1990; Wong et al., 1995). In addition, a second subpopulation of ETB receptors is located on smooth muscle cells and mediates vasoconstriction (Shetty et al., 1993). Therefore, in PAEC the effects of tezosentan are likely attributable exclusively to ETB receptor antagonism, whereas in lambs the effects of both ETA and ETB receptor antagonism are likely manifest. This is an important point as there are differential effects of ET-1 on H2O2 production in PAEC and pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMC) (Wedgwood and Black, 2005). ET-1 increases H2O2 production, in an ETA receptor dependent manner, in PASMC monocultures, and fetal PAEC/PASMC co-cultures. However, in PAEC monoculture, ET-1 decreases H2O2 levels, in an ETB receptor dependent manner (Wedgwood and Black, 2005). In this study we extended these findings to show that ET-1 decreases stimulatory eNOS phosphorylation at pSer1177 and increases the phopshorylation of the inhibitory site at Thr495. Together these changes in phosphorylation lead to a decrease in NOx levels in PAEC. These changes correlate with an increase in catalase activity. Thus, the findings of this study add to a growing body of literature that indicates that reactive oxygen species in general, and H2O2 in particular, are important in the regulation of signaling within the pulmonary vasculature. The results of the present study indicate that ET-dependent alterations in catalase activity play an important role in modulating H2O2 levels in lambs exposed to increased PBF, presumably due to alterations in its clearance. However, it is worth noting that we did not determine if there were alterations in H2O2 production in our models. The dismutation of superoxide, by superoxide dismutase, is the primary source of H2O2 within the vasculature. Therefore, a decrease in superoxide production might also lead to decreased H2O2 levels under conditions of increased PBF. However, our previous studies are not consistent with this mechanism, as we have shown increased superoxide production secondary to acutely increased PBF in a fetal lamb model of constriction of the ductus arteriosus (Hsu et al., 2010) as well as increases in superoxide in lambs with chronically increased PBF (Oishi et al., 2008).

Opening of the aortopulmonary shunt resulted in a significant increase in PBF, more than doubling in each group. This increase in PBF must be associated with an increase in shear stress, but it is important to recognize that shear stress was not measured directly in the lambs and that levels of shear stress likely differ with location within the pulmonary vascular bed. Nevertheless, our model is powerful in that, unlike physiologic increases in PBF such as those that occur with exercise, we created a pathologic situation in which the pulmonary to systemic blood flow ratio is greater than one. The palliation of several congenital cardiac defects that is often complicated by dynamic elevations in PVR, is associated with a similar physiology. In addition, the pathophysiology of various disease processes that can lead to pulmonary vascular dysfunction likely involves pathologic increases in PBF. For example, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, a known etiology of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn, is often associated with ipsilateral pulmonary hypoplasia, which results in abnormally increased PBF to the contra-lateral lung (Moreno-Alvarez et al., 2008). Pneumonectomy and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension with asymmetric lesions would also increase PBF to portions of the pulmonary circulation (Mercier et al., 2009). Furthermore, in patients with all types of pulmonary arterial hypertension, disease progression often results in obstructive pulmonary arteriopathy, which can lead to regional increases in PBF and shear stress in other less affected portions of the lung (Galie et al., 2008). Therefore, the novel signaling interactions demonstrated in the present study may have implications for a number of disease processes.

In summary, we found that the compensatory pulmonary vascular constriction that limits PBF in lambs after the placement of an aortopulmonary shunt is mediated, at least in part, by ET receptor activation, increased catalase phosphorylation and activity, decreased H2O2 levels, modulation of eNOS phosphorylation, and reduced NO production. ET receptor antagonism during increased PBF reverses this signaling, preserves NO generation, and prevents the compensatory increase in PVR.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported in part by grants HD047349 (to PO), HL60190 (to SMB), HL67841 (to SMB), HL72123 (to SMB), HL70061 (to SMB), HL084739 (to SMB), HD057406 (to SMB), HL61284 (to JRF), all from the National Institutes of Health, a Transatlantic Network Development Grant from the LeDucq Foundation (to SMB and JRF), an SDG from the AHA (SS), and Seed Awards from the GHSU Cardiovascular Discovery Institute (SK and SS). RR was supported in part by NIH training Grant, 5T32HL06699 respectively. The authors would like to thank Michael Johengen, M.S., Satish Noonepalle, MS and Cynthia Harmon, B.S. for their expert technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- Arai H, Hori S, Aramori I, Ohkubo H, Nakanishi S. Cloning and expression of a cDNA encoding an endothelin receptor. Nature. 1990;348:730–732. doi: 10.1038/348730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter D, Larkin H, Chang A, Morris E, O’Neill J, Curtis J. Superoxide dismutase and catalase do not affect the pulmonary hypertensive response to group B streptococcus in the lamb. Pediatr Res. 2001;49:181–188. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200102000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimmeler S, Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Hermann C, Busse R, Zeiher AM. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature. 1999;399:601–605. doi: 10.1038/21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald RK, Oishi P, Ovadia B, Ross GA, Reinhartz O, Johengen MJ, Fineman JR. Tezosentan, a combined parenteral endothelin receptor antagonist, produces pulmonary vasodilation in lambs with acute and chronic pulmonary hypertension. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004;5:571–577. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000137357.52609.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Dimmeler S, Kemp BE, Busse R. Phosphorylation of Thr(495) regulates Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity. Circ Res. 2001;88:E68–E75. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.092677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratz S, Fineman JR, Gorlach A, Sharma S, Oishi P, Schreiber C, Kietzmann T, Adatia I, Hess J, Black SM. Early determinants of pulmonary vascular remodeling in animal models of complex congenital heart disease. Circulation. 2011;123:916–923. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.978528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton D, Gratton JP, McCabe TJ, Fontana J, Fujio Y, Walsh K, Franke TF, Papapetropoulos A, Sessa WC. Regulation of endothelium-derived nitric oxide production by the protein kinase Akt. Nature. 1999;399:597–601. doi: 10.1038/21218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton D, Gratton JP, Sessa WC. Post-translational control of endothelial nitric oxide synthase: why isn’t calcium/calmodulin enough? Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2001;299:818–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galie N, Manes A, Palazzini M, Negro L, Marinelli A, Gambetti S, Mariucci E, Donti A, Branzi A, Picchio FM. Management of pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital systemic-to-pulmonary shunts and Eisenmenger’s syndrome. Drugs. 2008;68:1049–1066. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200868080-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu JH, Oishi P, Wiseman DA, Hou Y, Chikovani O, Datar S, Sajti E, Johengen MJ, Harmon C, Black SM, Fineman JR. Nitric oxide alterations following acute ductal constriction in the fetal lamb: a role for superoxide. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;298:L880–887. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00384.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Sud N, Fonseca FV, Hou Y, Black SM. Shear stress stimulates nitric oxide signaling in pulmonary arterial endothelial cells via a reduction in catalase activity: role of protein kinase C delta. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;298:L105–116. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00290.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurindo FR, Pedro Mde A, Barbeiro HV, Pileggi F, Carvalho MH, Augusto O, da Luz PL. Vascular free radical release. Ex vivo and in vivo evidence for a flow-dependent endothelial mechanism. Circ Res. 1994;74:700–709. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.4.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullan DM, Bekker JM, Parry AJ, Johengen MJ, Kon A, Heidersbach RS, Black SM, Fineman JR. Alterations in endogenous nitric oxide production after cardiopulmonary bypass in lambs with normal and increased pulmonary blood flow. Circulation. 2000;102:III172–178. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.suppl_3.iii-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercier O, Sage E, de Perrot M, Tu L, Marcos E, Decante B, Baudet B, Herve P, Dartevelle P, Eddahibi S, Fadel E. Regression of flow-induced pulmonary arterial vasculopathy after flow correction in piglets. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2009;137:1538–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.07.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michell BJ, Chen Z, Tiganis T, Stapleton D, Katsis F, Power DA, Sim AT, Kemp BE. Coordinated control of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase phosphorylation by protein kinase C and the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17625–17628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100122200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooradian DL, Hutsell TC, Keefer LK. Nitric oxide (NO) donor molecules: effect of NO release rate on vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation in vitro. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 1995;25:674–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes D, Loscalzo J. Pulmonary hypertension: newer concepts in diagnosis and management. Clinical Cardiology. 1997;20:676–682. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960200804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Alvarez O, Hernandez-Andrade E, Oros D, Jani J, Deprest J, Gratacos E. Association between intrapulmonary arterial Doppler parameters and degree of lung growth as measured by lung-to-head ratio in fetuses with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;31:164–170. doi: 10.1002/uog.5201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi P, Azakie A, Harmon C, Fitzgerald RK, Grobe A, Xu J, Hendricks-Munoz K, Black SM, Fineman JR. Nitric oxide-endothelin-1 interactions after surgically induced acute increases in pulmonary blood flow in intact lambs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H1922–1932. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01091.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi PE, Wiseman DA, Sharma S, Kumar S, Hou Y, Datar SA, Azakie A, Johengen MJ, Harmon C, Fratz S, Fineman JR, Black SM. Progressive dysfunction of nitric oxide synthase in a lamb model of chronically increased pulmonary blood flow: a role for oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L756–766. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00146.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafikov R, Fonseca FV, Kumar S, Pardo D, Darragh C, Elms S, Fulton D, Black SM. eNOS activation and NO function: structural motifs responsible for the posttranslational control of endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity. Journal of Endocrinology. 2011;210:271–284. doi: 10.1530/JOE-11-0083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Takuwa Y, Miyazaki H, Kimura S, Goto K, Masaki T. Cloning of a cDNA encoding a non-isopeptide-selective subtype of the endothelin receptor. Nature. 1990;348:732–735. doi: 10.1038/348732a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searles CD. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C803–816. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00457.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Sun X, Kumar S, Rafikov R, Aramburo A, Kalkan G, Tian J, Rehmani I, Kallarackal S, Fineman JR, Black SM. Preserving mitochondrial function prevents the proteasomal degradation of GTP cyclohydrolase I. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2012;53:216–229. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaul PW. Regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase: location, location, location. Annual Review of Physiology. 2002;64:749–774. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.081501.155952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shetty SS, Okada T, Webb RL, DelGrande D, Lappe RW. Functionally distinct endothelin B receptors in vascular endothelium and smooth muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;191:459–464. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sud N, Black SM. Endothelin-1 impairs nitric oxide signaling in endothelial cells through a protein kinase Cdelta-dependent activation of STAT3 and decreased endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression. DNA and Cell Biology. 2009;28:543–553. doi: 10.1089/dna.2009.0865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SR, Chen K, Keaney JF., Jr Hydrogen peroxide activates endothelial nitric-oxide synthase through coordinated phosphorylation and dephosphorylation via a phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent signaling pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:6017–6024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tworetzky W, Moore P, Bekker JM, Bristow J, Black SM, Fineman JR. Pulmonary blood flow alters nitric oxide production in patients undergoing device closure of atrial septal defects. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2000;35:463–467. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00576-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedgwood S, Bekker JM, Black SM. Shear stress regulation of endothelial NOS in fetal pulmonary arterial endothelial cells involves PKC. Am. J. Physiol. - Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2001;281:L490–L498. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.2.L490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedgwood S, Black SM. Endothelin-1 decreases endothelial NOS expression and activity through ETA receptor-mediated generation of hydrogen peroxide. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L480–L487. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00283.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong J, Vanderford PA, Winters J, Soifer SJ, Fineman JR. Endothelinb receptor agonists produce pulmonary vasodilation in intact newborn lambs with pulmonary hypertension. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1995;25:207–215. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199502000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]