Abstract

Social scientists generally seek to explain welfare-related behaviors in terms of economic choice, social structural, or culture of poverty theories. Because such explanations incompletely account for nativity differences in public assistance receipt among those of Mexican origin, this paper draws upon the sociology of migration and culture literatures to develop alternative materialist-based cultural repertoire hypotheses to explain the welfare behaviors of Mexican immigrants. We argue that immigrants from Mexico arrive and work in the United States under circumstances fostering employment-based cultural repertoires that, compared with natives and other immigrant groups, encourage less welfare participation (in part because such repertoires lead to faster welfare exits) and more post-welfare employment, especially in states with relatively more generous welfare-policies. Using individual-level data predating Welfare Reform from multiple panels of the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), merged with state-level information on welfare-benefit levels, we assess these ideas by examining immigrant-group differences in welfare receipt, retention, and transition to employment across locales with varying levels of welfare benefits. Overall, the results are consistent with the notion that cultural repertoires incline Mexican immigrants to utilize welfare not primarily to avoid work, cope with disadvantage, or perpetuate a culture of dependency, but rather mostly to minimize employment discontinuities. This result carries important theoretical and policy implications.

Welfare-related behaviors have generally been viewed by the public as well as by academic scholars and policy analysts as resulting from the choices individuals make in seeking to maximize income while minimizing work. For example, it is widely accepted that decisions regarding whether to work or participate in welfare can be manipulated by adjusting the incentives attached to welfare receipt (such as by altering welfare benefit levels) (Moffitt 1992). In 1996, the assumption that a considerable portion of welfare receipt derived from perverse incentives not to work played a prominent role in the passage of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) (hereafter the Welfare Reform Act) (DeParle 2004). The logic of economic choice thus provided a main justification for passing welfare legislation reform that sharply restricted access to public assistance. The restrictions passed included work requirements for eligibility and time limits for length of receipt (Blank and Haskins 2001). That the numbers of persons on public assistance rolls declined significantly for several years after passage of the Welfare Reform Act, not just because of the technology-driven economic boom of the late 1990s but also as a result of the shift in welfare policy (Grogger and Karoly 2005), lends credence to the idea that substantial numbers of recipients may in fact have been participating in welfare more for reasons of convenience than need.

Such broad characterizations, however, gloss over important sources of social structural and cultural heterogeneity across both individuals and groups. For example, structural heterogeneity may involve variation in dire necessity deriving from socioeconomic disadvantage. A great deal of research attention has been devoted to documenting the significant numbers of recipients in welfare populations who face virtually insurmountable structurally induced barriers to work and thus enjoy little recourse other than reliance on public assistance (e.g., (Bane and Ellwood 1994; Wilson 1987; Wilson 1996). For example, even after welfare reform was passed, many recipients on the verge of exhausting their time limits (from perhaps a quarter to a third) still confronted such multiple and serious obstacles to employment (poor physical and mental health, very low levels of education, debilitating drug or alcohol abuse, domestic violence, and children with severe disabilities) that working was virtually impossible (Danziger 2001; Zedlewski and Loprest 2001). In subsequent years, many states at least partially restored eligibility for welfare for such persons (Grogger and Karoly 2005), in part because welfare reform helped to bring into relief the severity of the social-structural disadvantages facing such persons.

Apart from variation in incentives and social structural disadvantages, cultural heterogeneity may also affect welfare recipiency. Culture of poverty perspectives argue that welfare participation is driven by learned cultural inclinations away from self-reliance and toward dependence on welfare as an acceptable way of life (Mead 1986; Murray 1984). Such tendencies are often thought to become reinforced and thus to exist in exaggerated form among persons residing in areas with high concentrations of poverty (Auletta 1982). Opposite kinds of cultural orientations – such as unusually strong tendencies to seek employment, deeply ingrained work ethics, or values that stigmatize welfare participation – have not been emphasized in prior theories and research on welfare participation, perhaps owing, as some have noted (Bean, Feliciano, Lee, and Van Hook 2009; Patterson 2006), to a fear of appearing to “blame the victim”. As a corrective, the present research invokes the idea of materialist-based cultural repertoires to help explain distinctively low net welfare receipt among Mexican immigrants compared to other immigrant groups and natives. Cultural repertoires consist of ideas, customs and orientations that, while often originating in materialist conditions, may also take on force of their own and serve to help people establish priorities, cope with life necessities, and resolve day-to-day work and family dilemmas (Lamont 1992; Lamont 2000).

Our utilization of such notions draws upon sociology of culture perspectives that emphasize the constitutive aspects of culture, or culture as integral to all things social in that “the diverse meanings and beliefs that individuals and groups adopt to interpret their life experiences … are in turn consequential in their social lives” (Binder, Blair-Loy, Evans et al. 2008); 10). Also, we take seriously Skrentny’s (2008) suggestion that the cultural study of American immigrant groups is likely to benefit from comparative approaches that consider such groups as “possibly shaped by the culture of their origins” (p. 60). Thus, we assume that relatively enduring cultural repertoires and scripts may emerge out of previous collective experiences and influence subsequent individual and group behaviors (Lamont 2000; Sewell 1992; Swidler 1986; Wuthnow 1987). These may even include the immigration experience itself, as Weber (1968) noted in defining ‘“ethnic groups” as those that “entertain a subjective belief in their common descent because of similarities of physical type or of customs, or both, or because of memories of … migration” (emphasis added, p. 389).

In particular, we suggest that strong pro-employment-related cultural orientations characterize Mexican immigrants and discourage welfare receipt, except when participation is relied upon for transitional financial support between jobs. We introduce findings from a voluminous research literature to document that Mexican immigrants are predominantly unauthorized working-class labor migrants (meaning that compared with other groups they disproportionately face circumstances that foster pro-employment cultural repertoires). i This suggests that Mexican immigrants are likely to show a greater likelihood to exit welfare faster in order to take employment than other immigrant groups. Moreover, unlike economic choice theory, it also implies that because cash benefits provide resources that can help in looking for work, this pattern will emerge most strongly when Mexican immigrants reside in states providing greater welfare benefits. By contrast, other immigrant groups, whose employment-oriented repertoires are weaker and perhaps not even strong enough to override the influence of welfare economic incentives, are likely in such states to exhibit just the opposite pattern (i.e., higher participation, slower exit, and lower post-receipt employment).

Theoretical Models of Welfare Receipt and the Results of Prior Research

Rational choice perspective

The dominant perspective adopted in most analyses of welfare is economic choice theory. This approach sees welfare-related behaviors as resulting from individual calculations of the relative costs and benefits of participation weighed against alternative options (Bane and Ellwood 1994; Moffitt 1992). The greater the benefits from welfare receipt relative to the returns from working, the greater the welfare participation. Consistent with this perspective, research shows in general that higher welfare guarantees lead to lower employment among single mothers (Burtless 1990; Moffitt 1992), more families on welfare (Ashenfelter 1983; Plotnick 1983), longer welfare spells (Bane and Ellwood 1994; Plotnick 1983; Robins, Tuma, and Yaeger 1980), and fewer job-related exits from welfare (Bane and Ellwood 1994). Thus, this framework predicts that individuals living in states where welfare benefits are high compared to states where benefits are low would be more likely to receive and stay on public assistance and less likely to transition to work after leaving such assistance. Nothing in the perspective itself would offer a basis for thinking that immigrants who have been in the country longer would be more likely to seek public assistance.

Structural disadvantage perspective

A social structural perspective envisions welfare receipt resulting to an appreciable degree from lower social and economic standing or well-being. Indeed, a certain degree of economic need (low income, or none at all) is a prerequisite for eligibility (Bane and Ellwood 1994; Handler and Hollingsworth 1971; Katz 1986). Economic disadvantage is also strongly positively associated with other disabilities that hamper employment (very low education, mental illness, physical disability, young children with disabilities, and cognitive impairments). In short, welfare receipt in this view derives from need rather than choice. The debilitating conditions stemming from structural disadvantages are seen as presenting insurmountable obstacles to finding and holding employment for individuals whose survival possibilities depend substantially on public assistance. Within this framework, if immigrants evince higher welfare receipt than natives, the reason would presumably relate substantially to the greater social and economic disadvantages faced by immigrants. In terms of state-level comparisons, the approach would predict little difference in welfare behaviors between disadvantaged individuals living in states providing higher benefits compared to those living in lower benefit states, all else equal. Similarly, immigrants residing longer in the country would not be expected to increase their participation unless they became more disadvantaged.

Culture of poverty perspective

The culture of poverty approach argues that some people participate in public assistance programs due to learned differences in the acceptability of welfare. This point of view often claims a potential “moral hazard” inheres in welfare (i.e., simply the availability of welfare may encourage participation). It thus tends to see public assistance itself as promoting values and orientations that foster its usage. Whether such orientations are thought to emerge from severe long-term economic disadvantage (Auletta 1982) or the loss of central-city jobs and lack of geographic mobility associated with residence in inner-city neighborhoods (Wilson 1987; Wilson and Neckerman 1996), the perspective frames such cultural orientations as acquired and reinforced by welfare’s existence and by recipients’ isolation from other more advantaged members of society. Hence, culture of poverty theory envisions welfare as reflecting self-defeating tendencies to enter and remain on welfare, with such inclinations taking on influence of their own and fostering further welfare receipt, especially because such values and orientations are thought to be strengthened by living in areas where persons with similar orientations are concentrated (see Bane and Ellwood (1994) and Rainwater (1987) for explications of this view in regard to welfare behavior). In terms of state-level comparisons, the culture of poverty perspective, like the economic choice perspective, would expect immigrants in higher benefit states to exhibit higher participation, slower exit, and less frequent post-welfare employment, all else equal. However, unlike the economic choice view, this perspective would expect immigrants living in the country longer to have more time to acculturate into higher welfare receipt.

Studies assessing these theories

Studies of immigrant welfare recipiency during the 1970s and 1980s concentrated heavily on the important policy-relevant question of whether immigrants were more likely to receive welfare than natives, sometimes after accounting for demographic and socioeconomic differences (see (Bean, Stevens, and Van Hook 2003) for a review). Especially when poverty or economic status was controlled, such research typically found that immigrants were less likely than natives to receive welfare (Blau 1984; Jensen 1991; Tienda and Jensen 1986). Subsequently, however, overall composite measures of immigrant welfare receipt showed increases in usage during the 1980s, both absolutely and relative to natives (Bean, Van Hook, and Glick 1997; Borjas and Hilton 1996). But, further research revealed that among the different types of cash assistance, only immigrant receipt of Supplemental Security Income (SSI) increased over the period. Moreover, all else equal, only SSI receipt exceeded that of natives; receipt of Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) remained steady at levels lower than those of natives (Bean et al. 1997; Ono and Becerra 2000), all else equal.

Other research investigating the extent to which measures of overall welfare receipt increased the longer immigrants reside in the country seemed also initially to suggest that rates of public assistance usage rise the more exposure immigrants have to the United States (Borjas 1990; Borjas 1998). However, when shifts in the demographic composition of immigrants and immigrant families over time were taken into account, a different conclusion emerged (Hu 1998), namely that immigrants were aging out of categories that made them eligible for AFDC and into categories that made them eligible for SSI (attaining age 65 or older). Further, since a greater percentage of immigrants received SSI than AFDC, the net effect was a trend showing increasing overall welfare usage over time. Moreover, when only the elderly were examined, duration of residence in the country was negatively related to SSI recipiency (Hu 1998; Van Hook 2000). Thus, results that at first blush appeared to constitute support for the idea that immigrants were acculturating into welfare participation actually turned out to reflect aging effects (Bean et al. 2003; Van Hook and Bean 1999).

To be sure, some prior research seemed to support the idea that immigrants (and natives) may be subject to the kinds of forces emphasized in the culture of poverty model, although it has emphasized contextual effects. For example, Galster, Metzger et al. (1999) found in an analysis of aggregated group-level data that immigrant groups living in neighborhoods with high levels of public assistance usage in 1980 tended to experience declines in the percentage employed among those ages 16 to 64 between 1980 and 1990. However, it is worth noting that this research did not find that high neighborhood public assistance either significantly lowered educational attainment, income, or the percentage in professional occupations or raised poverty or self-employment. Hao and Kawano (2001) find a positive relationship between the average level of economic inactivity among co-ethnics in a neighborhood and single mothers’ use of AFDC for both immigrants and natives. Finally, Borjas and Hilton (1996) observed that the particular welfare program used by previous entry cohorts of a country-of-origin group is associated with the welfare program used by more recent entry cohorts of the same group. In the authors’ words (1996): 602), “This correlation suggests that there might be information networks operating within ethnic communities which transmit information about the availability of particular types of benefits to newly arrived immigrants.”

More important, analysts invoking culture of poverty explanations have also argued that the availability of welfare benefits in the United States draws “welfare-prone” newcomers to high-benefit states, where the residential concentrations of immigrants further strengthen tendencies to rely on welfare (Borjas 1990; Borjas and Hilton 1996). But studies of immigrant welfare recipiency (as opposed to native recipiency) have yet to examine the relationship between the generosity of welfare benefits and immigrant welfare participation. While the results of some research have suggested that immigrants, particularly refugees (Zavodny 1999), are more likely to locate in and move to states with higher benefits (Borjas 1999; Dodson 2001) -- findings that have been interpreted as consistent with the idea that welfare attracts immigrants to the country -- such studies have not actually assessed whether immigrant welfare receipt is higher in those areas. Even if immigrants were more likely to settle in or move to higher-benefit states, this does not necessarily mean they would be more likely to participate in welfare in those states, particularly if such states also offer greater possibilities for employment and better amenities.

Employment-Related Cultural Repertoires and their Implications for Welfare Participation

The fact that many immigrants, especially Mexican immigrants, tend to utilize public assistance less than comparable natives constitutes a pattern repeatedly replicated in research now for more than three decades (Bean et al. 2003; Tienda and Jensen 1986). However, neither economic choice, structural disadvantage, nor culture of poverty theories adequately account for this result. The present research thus draws upon conceptualizations of materialist-based cultural repertoires, together with the findings of previous research about the logic of Mexican migration and the nature of Mexican immigrant working-class employment to develop alternative hypotheses about Mexican immigrant welfare participation. Such a framework envisions materialist conditions as shaping the formation of cultural repertoires that may affect such behavior. Though portrayed as rooted in structural circumstances, such cultural resources may be conceptualized as exerting their own independent influence on behaviors and outcomes, even though the strength of such tendencies may fluctuate across various situational contexts (Swidler 2000).

An overwhelming emphasis on finding and sustaining employment among Mexican immigrants originates in and is reinforced by social-structural conditions that encourage migration decisions for purposes of seeking work (Massey and Denton 1987; Portes and Bach 1985). Mexican immigrants, far more than other types of immigrants (refugees or family reunification immigrants, for example) arrive in the United States as unauthorized entrants and as low-skilled labor migrants strongly expecting to work to provide for their families (Bean and Stevens 2003; Chávez 2007; Dohan 2003; Fix and Passel 1994; Sánchez 1993). Not only are they leaving labor market situations in their countries of origin that offer virtually no prospect of employment in the towns and villages from which the majority of such migrants come (Stark 1993), strong expectations exist in both their families and communities that as teenagers they will undertake migration to the United States expressly to work (Kandel and Massey 2002). Job opportunities are evaluated more for their family/household social insurance potential (i.e., for the likelihood they will reduce family/household financial risk) than for their ability to provide relative individual wage gains (Massey, Arango, Hugo et al. 1998; Stark 1991; Stark and Taylor 1989). The unauthorized status characterizing most entrants at the time of initial arrival only reinforces such inclinations, primarily because it makes them more vulnerable and heightens their need for steady work (Bean and Stevens 2003). Given the socially structured underpinnings of labor migration, and given the extensive reliance of migrants on social networks to obtain employment (a result in part of their unauthorized status), Mexican immigrants generally can more easily find work in the United States than the members of other immigrant groups (Waldinger 2001; Waldinger and Lichter 2003).

Because such circumstances inculcate strong pro-employment cultural repertoires, when Mexican immigrants are in need of public assistance, they are more likely to view welfare as temporary. This may thus help them avoid the “moral hazard” risks involved in welfare participation. Under such conditions, financial assistance, even if in the form of welfare, can foster economic integration rather than promote dependency (Bean et al. 2003). The United States has not traditionally provided settlement assistance to immigrants, except in the case of refugees. Tellingly, persons who enter the country as refugees subsequently experience greater earnings growth than other kinds of immigrants (Cortes 2004). Moreover, evidence generally suggests that higher welfare guarantees may in fact help the working poor escape poverty. Butler (1996), for example, finds that higher welfare benefits hasten poverty exits for those who become single mothers as adults. The availability of supplementary monetary assistance—which can be used for investments such as transportation, work clothing, job training, and rental deposits—can help the economically disadvantaged escape poverty, particularly among those whose goals are fundamentally to work (Menjivar 1997; Zhou and Bankston 1998). Thus, family/household and employment-related imperatives for migration among Mexican immigrants, together with strong working-class expectations about the importance and necessity of remaining attached to the labor market (Lamont 2000; Rodgers 1974), may operate not only to reduce public assistance recipiency among Mexican immigrants by shortening the duration of welfare spells, but also to increase the likelihood of spells ending in employment.

Research Approach, Data, and Methods

Research Approach

To evaluate the above theoretical ideas, we examine welfare receipt, the duration of welfare spells (i.e., the likelihood of leaving welfare), and employment following welfare spells among immigrant and native women across multiple panels of the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) from 1990 to 1996. We adopt a longitudinal and comparative approach because former recipients who depart welfare relatively quickly and find jobs show they are not dependent on welfare, particularly when the recipients live in states providing generous welfare benefits. We first assess whether culture-of-poverty factors dominate welfare decisions by examining the extent to which immigrants with greater exposure to the United States (those who first came to the country as children) are more likely to receive welfare, exhibit longer spells, and show lower employment following welfare receipt than immigrants who came to the United States as adults. We then assess the pro-employment cultural repertoire hypothesis by examining the extent to which Mexican immigrants are less likely to receive welfare, more likely to exit, and more likely to work after welfare than other immigrant or native minority groups, especially native blacks. We then assess the extent to which lower levels of welfare recipiency, shorter welfare spells, and relatively higher post-welfare employment are more characteristic of Mexican immigrants living in places that provide the most support (i.e., in states with higher welfare benefits).

We confine our analysis of immigrant and native welfare-related behaviors to the first half of the 1990s before the passage of welfare reform. Prior to this, there were no special restrictions related to migration status on legal immigrants’ eligibility for AFDC (Huber and Espenshade 1997; Zedlewski and Giannarelli 2001), although unauthorized immigrants were ineligible. However, welfare reform barred legal immigrants entering after August 22, 1996, from receiving TANF for the first five years after entry (although states were allowed to grant exceptions). The level of immigrants on welfare subsequently fell dramatically (Borjas 2001; Fix and Passel 2002) for reasons related to improving economic conditions and welfare policy changes (Chernick and Reimers 2004; Grogger and Karoly 2005; Haider, Schoeni, Bao, and Danielson 2004; Lofstrom and Bean 2002; Swingle 2000). If we were to include the post-reform period in our analyses, it could appear as if immigrants were substantially less likely to receive welfare than natives when in fact, at least a portion of the difference could be due to differences in factors determining eligibility.

Among the various welfare programs, we focus on Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC). Before it was replaced by Temporary Aid for Needy Families in 1996, AFDC provided cash welfare payments for needy children and their caretakers (usually parents) in the event one parent was deceased or absent from the home continuously. The AFDC-UP (Unemployed Parent) program also provided assistance to couples who were needy because of unemployment of one of the parents. Thus, although most AFDC families were headed by single mothers, about seven percent in 1995 were headed by married couples (U.S. House of Representatives 1996). We focus on AFDC because the work disincentives of this type of program are likely to be stronger than for programs that provide in-kind assistance (e.g., Food Stamps) or cash assistance to the elderly or disabled (e.g., SSI) (Moffitt 1992). As such, this type of welfare receipt lends itself to the explanations offered by economic choice, culture-of-poverty or cultural-repertoire theories, each of which takes into account orientations and/or choices about work.

Much of the prior research on immigrant welfare recipiency compares immigrants with natives of all racial and ethnic groups. But this approach makes it difficult to control statistically for race/ethnicity while simultaneously examining national-origin group differences. Because policy debates about immigrant incorporation frequently focus on the question of whether immigrants will eventually exhibit the socioeconomic patterns displayed by non-Hispanic whites or African Americans, we opt here to restrict the native comparison groups to these two. Non-Hispanic whites tend to have more favorable economic outcomes in general, and lower levels of welfare recipiency in particular, than African Americans, so we distinguish between these two groups in all comparisons with immigrants.

Data

We use longitudinal data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) to explore the dynamics of welfare-related behaviors among immigrant and native women. The SIPP is a longitudinal survey that interviews respondents every four months for roughly three years. We combine several panels of the SIPP (the 1990the 1991the 1992, and 1993 SIPP panels). Each of the four SIPP panels includes a separate, independent sample that is interviewed every four months for roughly 3 to 4 years. For example, the 1990 Panel includes individuals who were interviewed up to 8 times over a period of 32 months between 1990 and 1992, and the 1991 Panel includes an entirely new sample that was interviewed up to 8 times over a period of 32 months between 1991 and 1993. By pooling the four panels, we obtain a sufficiently large sample to examine in depth the dynamics of AFDC recipiency and post-welfare employment among immigrants. Because the pooled SIPP samples includes many more natives than immigrants (and far more than is necessary for the analyses), we randomly selected a sample of non-Hispanic white natives and non-Hispanic black natives from the pooled sample (10 percent white non-recipients, 20 percent white recipients, 20 percent black non-recipients, and 50 percent black recipients), added it to the 100 percent sample of foreign-born respondents, and adjusted the sampling weights appropriately. Hereafter, we refer to non-Hispanic white natives simply as “white natives” and non-Hispanic black natives as “black natives.” The analytical research sample is limited to women living with a minor child age 0–17 in their immediate family at wave 1 and who had a valid wave 2 interview (because the variables related to migration and nativity were asked only at wave 2), including only original respondents and excluding those who joined sample households after the wave 1 interview. Both married and unmarried women are included because married couples were eligible for AFDC under the Unemployed Parent program. Although married women were much less likely to receive AFDC than unmarried women (2.2 percent vs. 28 percent of mothers in our sample), a substantial proportion of AFDC recipients were married: 16 percent of native and 30 percent of immigrant recipients.

Further commentary is in order about the fact that the sample is restricted to women. The ideas introduced above about strong pro-employment cultural repertoires pertain to both Mexican-origin men and women. That Mexican men maintain strong pro-employment inclinations is revealed in the fact that their education-adjusted labor force participation rates are higher than those of other immigrant groups (Bean, Gonzalez Baker, and Capps 2001; Waldinger 2001). The research literature on employment indicates a similarly strong work orientation among Mexican women, although evidence of this does not fully show up in official labor force participation rates because Mexican-immigrant women are disproportionately likely to be employed as street vendors, child care workers, domestics, piece-rate workers, and other workers in the informal economy, jobs that often involve working at unconventional sites and activities that are more likely not to be reported in official surveys (Melville 1988; Ojeda de la Peña 2007; Ruiz 1998; Segura 2007).

We further eliminate from the sample those born in Puerto Rico or other U.S. outlying areas because they comprise a group that may not be justifiably classified as native (because they share many characteristics of legal immigrants), but also do not fit the immigrant category because they are U.S. citizens by birth. We also eliminate refugees because our data contain too few refugees to produce stable estimates for this group. Moreover, refugees are inappropriately lumped together with other immigrants in analyses of welfare behaviors. Even prior to welfare reform, U.S. immigration policy established different eligibility rules for receiving public assistance in the case of persons entering as refugees versus the case of persons entering as legal permanent residents (Gordon 1987; Vialet 1993). We identify refugees as those coming from the eleven nations almost all of whose immigrants to the United States during the 1980s were refugeesii. Finally, we drop the most recently arrived immigrants (in the U.S. fewer than three years) because many of these immigrants were ineligible for welfare because of “sponsor deeming” practices prior to PROWRA (whereby the income of an immigrant”s sponsor was counted along with the immigrant’s income when determining eligibility for welfare) (Huber and Espenshade 1997; Zedlewski and Giannarelli 2001).

Our final sample includes 4,071 immigrant women (of all racial and ethnic groups) and 9,265 native women (4,801 non-Hispanic white and 4,464 black natives). We constructed a longitudinal data file that includes an observation for each individual for each interview they were in the SIPP (every four months for 3 to 4 years). The number of person-interviews in the combined SIPP panels is 94,205. Attrition was low after the second wave and similar for immigrants and natives. Of the original respondents interviewed in the second wave, about 90 percent of immigrants and natives were interviewed (or were interviewed by proxy) in all subsequent waves.

Measures

Welfare Receipt

We measure AFDC receipt for the four-month reference period prior to each interview, coding women as receiving welfare if they either reported receiving benefits or were reported as being covered by the program. This ensures that AFDC beneficiaries who did not personally receive or report a welfare payment are still counted as recipients. Although the SIPP collected monthly information about AFDC receipt, we count women as recipients if they received welfare during any month during the four-month reference period. We disregard the more detailed monthly data because respondents tend to report welfare receipt all four months or none at all in the reference period, suggesting that month-to-month reporting of AFDC is not very accurate (Kalton and Lepkowski 1992). The results presented here on spell duration thus capture gradual changes rather than erratic month-to-month fluctuations in AFDC receipt.

We examine two dimensions of AFDC receipt: prevalence and exit from the AFDC program. Prevalence is measured as the percentage who report receiving AFDC at any given interview. Exit from the program is measured as the percentage of recipients who report leaving AFDC. Respondents reported the month and year they started receiving AFDC for current spells, and we use this information to estimate and statistically control for the duration of all welfare spells, even those already ongoing at the time of the first interview, thus avoiding left-truncation bias (Guo 1993)iii.

Employmen

In addition to welfare prevalence and exit, we examine employment status following welfare spells to assess the likelihood of leaving welfare for a job. Among welfare leavers, those employed at least 20 hours per week on average during the four months following a welfare spell are treated as having an “employment exit,” while the remaining welfare leavers are coded as having a “non-employment exit.” We use 20 hours of employment as a cut-off because it is unlikely that women with fewer hours would be able to support their families without other support. To provide descriptive statistics on the relative speed at which recipients leave welfare, we use life tables to estimate the probability that welfare recipients leave welfare for any reason and for employment within one year of the start of a welfare spell (Preston, Heuveline, and Guillot 2001)iv.

Generational Status, Duration of U.S. Residence

The SIPP collects information on migration history at the time of the second interview. We construct a categorical variable that distinguishes among white and black native women, foreign-born women who arrived as children age 0–14 (the 1.5 generation), and foreign-born who arrived as adults ages 15+ (the immigrant generation). Where sample size permits, we subdivide the foreign-born by ethnicity (Mexican, other Hispanic, and non-Hispanic), and the immigrant generation by duration of residence in the United States (3–9 years and 10+ years).

Generosity of State Welfare Benefits

We examine the influence of the generosity of welfare benefits on welfare behaviors among immigrant and native women. State-level information on minimum state welfare benefits is obtained from the Department of Health and Human Services (Services 2000). Welfare benefit levels vary by state and year, and are measured as the combined annual dollar amount a single, non-working parent with two children could expect to receive in the form of food stamps and AFDC/TANF payments. All dollar amounts are adjusted to 1996 dollars using the Consumer Price Index, and divided by 100 (meaning that the variable is expressed in $100s).

Other Factors

We control for the influence of various indicators of socioeconomic status, family composition and other demographic characteristics in the multivariate models. As is common in research on welfare recipiency (Moffitt 1992), we control for non-wage, non-welfare income in the previous four months (logged) in order to take into account differences in income from assets, gifts, or inheritance. We also adjust for educational attainment (less than high school, high school and some college or technical school versus college graduate) to account for differences in potential wages. Other socio-demographic controls include marital status, living arrangements (residing with extended kin versus other), disability status, and age at baseline. All time-varying independent variables (income, education, living arrangements, and disability) are lagged by four months (i.e., by one interview) from the time the dependent variable is measured.

We also include various contextual controls. To capture geographical variations and trends in opportunities for employment, we use estimates of the seasonally adjusted monthly unemployment rate by state (estimates produced by the Bureau of Labor Statistics based on the Current Population Survey). The unemployment rates were attached to individual women’s records matching on state and year, and month. To account for possible variation in employment opportunities by labor-force sector, we control for the percentage of the labor force in the state and year in agricultural, forestry, or fishing; and the percentage in service occupations (estimates obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics). To adjust in part for geographic variations in group-level influences (such as social support from ethnic group members), we control for the percentage of the respondent’s nativity/race/ethnic group in the state (based on 1990 census estimates). To adjust for policy variations in the compatibility of welfare and work, we control for the state-level benefit reduction rate (the amount of AFDC income reduced for each additional dollar of earnings), which deviated from federal guidelines in states that obtained waivers during the pre-reform period (Blank and Haskins 2001). We use the formula used by Stapleton, Livermore, and Tucker (1997) to estimate the marginal tax and benefit reduction rate. Finally, we include a set of dummy variables indicating calendar year to account for period effects.

Analytical and Modeling Issues

To model AFDC receipt, we estimate logistic regression models of the likelihood of receiving AFDC using all person-interview observations (N = 79,479). To model exit from welfare, we estimate discrete-time event-history models (Allison 1984) of leaving AFDC using all person-interviews during which the respondent was observed as receiving AFDC until and including the interview they no longer reported receiving AFDC or were censored (i.e., no longer followed by the study) (N = 17,373). Finally, to model employment exits from welfare, we estimate competing risk hazard models predicting the probability of the type of exit from AFDC spells, in which we use the same analytic sample as for the AFDC-exit models but allow for competing outcomes: employment exit and non-employment exit versus staying on AFDC. The competing risk models are estimated using multinomial logistic regression, which allows for different intercepts and coefficients for each comparison (DeMaris 1992). To assess group differences in the relationship of state welfare benefit level with welfare behaviors, we include interaction terms between nativity/race/ethnic groups and state welfare benefit.

As noted above, attrition in the SIPP is low after the second wave and similar in pattern for immigrants and natives. Nevertheless, if attrition were associated with welfare dynamics, this could bias the estimates (Fitzgerald, Gottschalk, and Moffitt 1998). Therefore, for the models of AFDC exit and employment, we treat censorship (if it occurred prior to the last possible SIPP interview) as a possible outcome in addition to remaining on and exiting AFDCv. In general, neither nativity/race/ethnicity nor state welfare benefit level was significantly associated with attrition, nor did treating censorship as an additional possible outcome affect the results.

For all models, we adjust the standard errors for clustering of observations within individuals and primary sampling units (Chakrabarty 1989; Huber 1967; White 1980; White 1982). In addition, the models of welfare behaviors are weighted using adjusted sampling weights that take into account the unequal distribution of immigrants and natives across states. The adjusted weights match the cross-state distribution of native-born women with the immigrant distribution. This ensures that nativity differences in results do not derive from different distributions across states.

Research Results

Length of Residence in the Country

We first examine relationships between nativity and length of time in the United States and aspects of welfare behavior without considering the influence of other variables or how state-welfare benefit level might affect this association. The culture-of-poverty perspective predicts that immigrants would show higher levels of welfare receipt, evidence of longer welfare spells, and lower levels of post-welfare employment than natives. When other factors affecting welfare receipt are not controlled, the results generally conform to a culture-of-poverty pattern, particularly among non-Mexican immigrants. In the SIPP data examined here, all three immigrant groups (Mexican, “other Hispanic,” and non-Hispanic) are significantly more likely to receive AFDC than white natives, but significantly less likely than black natives (Table 1). Among the three immigrant groups, “other Hispanic” immigrants are the most likely to receive AFDC (18.6 percent versus 13.4 percent and 8.0 percent among Mexican and non-Hispanic foreign-born, respectively). The relatively high percentage on welfare among the other Hispanic groups can be partially explained by their longer welfare spells, as indicated by their lower exit rates within one year after receipt. Among women who report receiving AFDC, Mexican immigrants are significantly more likely to have exited welfare within one year (57.7 percent) than white (37.9%) or black natives (36.4%). But the percentages leaving welfare within one year among other Hispanic groups (24.7) and non-Hispanic immigrants (32.2) are not significantly different from white or black natives. To examine employment following welfare, we combine the other Hispanic and non-Mexican groups due to limitations in sample size. The results show similar patterns in that non-Mexican immigrants are significantly less likely to leave welfare for employment than white and black natives, while Mexican immigrants are just as likely to do so.

Table 1.

Percentage Receiving AFDC, Exiting AFDC, and Exiting AFDC with Employment, by Nativity, Generation, and Race/ethnicity

| % Receiving AFDC | % Exit AFDC within 1 year | %Emp. Exit within 1 year | |

|---|---|---|---|

| White Natives | 5.0b | 37.9 | 19.4 |

| Black Natives | 26.7a | 36.4 | 24.6 |

| Immigrants | 10.9ab | 43.9b | 18.8 |

| 1.0 Generation | 11.3ab | 40.9 | 14.5b |

| 1.5 Generation | 9.5abc | 56.2ab | 34.7ac |

| Mexican Immigrants | 13.4ab | 57.7ab | 26.6 |

| 1.0 Generation | 12.8ab | 56.2ab | 24.3 |

| 1.5 Generation | 15.3abc | 62.2ab | 31.3 |

| Non-Mexican Immigrants | 9.9ab | 30.8 | 12.4ab |

| 1.0 Generation | 10.7ab | 28.3a | 7.1ab |

| 1.5 Generation | 7.0abc | 45.7 | 42.2ac |

| Other Hisp. Immigrants | 18.6ab | 24.7 | --- |

| 1.0 Generation | 19.5ab | 19.1ab | --- |

| 1.5 Generation | 15.8abc | 44.1 | --- |

| Non-Hisp. Immigrants | 8.0ab | 32.2 | --- |

| 1.0 Generation | 8.8ab | 30.3 | --- |

| 1.5 Generation | 4.8bc | 46.6 | --- |

Source: 1990, 1991, 1992, and 1993 SIPP panels (longitudinal data). Sample: Women living with minor children (<18). The native sub-sample is restricted to non-Hispanic whites and African Americans, and the immigrant sample excludes those who are categorically ineligible for AFDC (i.e., less than 3 years in U.S.). See text for details.

significantly different from non-Hispanic white natives (p<.05)

significantly different from non-Hispanic black natives (p<.05)

1.5 generation is significantly different from the 1.0 Generation (p<.05)

The culture-of-poverty hypothesis also predicts that immigrant group rates will rise with increasing length of time spent in the country. As we can see from the generational breakdowns in Table 1, such a pattern is not borne out. In the cases of both the other Hispanic and non-Hispanic immigrant groups, welfare behaviors tend not to worsen going from the immigrant first to the 1.5 generation. AFDC receipt declines significantly, exit rates do not change, and employment exits increase significantly between the immigrant first and 1.5 generations. Such findings mostly run counter to culture-of-poverty predictions. Only Mexicans seem to reveal a pattern following the expectations of this hypothesis in that receipt may be higher in the 1.5 than the immigrant generation.

The Mexican results especially, however, may be substantially influenced by group differences in factors associated with eligibility for and receipt of welfare, such as socioeconomic status (i.e., education and non-wage income), marital status, and state economic structure and therefore may not reflect propensities to receive welfare or to work. We therefore also estimate multivariate models of the relationships between AFDC receipt and exit by generation and kind of immigrant group, net of controls. We present odds ratios from these models in Table 2. The basic pattern just noted above for the two non-Mexican groups does not change and, in fact, looks even more favorable in the sense that receipt appears to be lower and exit rates appear to be greater at longer durations of U.S. residence, although these effects reach statistical significance only in the case of non-Hispanics. Also, among non-Hispanic groups, significantly higher receipt relative to white natives occurs only among those in the country the shortest length of time within the immigrant generation and not in the 1.5 generation. However, in the case of Mexicans, after controlling for the effects of other factors, no significant differences appear between either the immigrant first or the 1.5 generation and natives. Thus, scarcely any evidence emerges supporting the culture-of-poverty idea that welfare receipt should be higher and spells longer among those here longer. As a consequence, we do not present any further results by length of time in the country.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios for Generational Status and Duration in the U.S. from Models of AFDC recipiency and AFDC exit†

| AFDC Recipiency

|

AFDC Exit

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| White Natives (ref.) | ||||

| Black Natives | 5.31*** | 5.32*** | 0.79 | 0.78 |

| Mexican, 1.0 Generation | 1.16 B | --- | 0.96 | --- |

| 5–9 years in U.S. | --- | 1.07 B | --- | 0.99 |

| 10+ years in U.S. | --- | 1.82 +BC | --- | 0.80 |

| Mexican, 1.5 Generation | 1.78 B | 1.80 B | 1.07 | 1.06 |

| Other Hispanics, 1.0 Generation | 3.89 *** | --- | 0.54 | --- |

| 5–9 years in U.S. | --- | 3.80 *** | --- | 0.67 |

| 10+ years in U.S. | --- | 4.22 *** | --- | 0.20 * b |

| Other Hispanics, 1.5 Generation | 2.38 * B | 2.39 * B | 1.02 | 1.03 |

| Non-Hispanics, 1.0 Generation | 2.84 *** B | --- | 0.30 *** B | --- |

| 5–9 years in U.S. | --- | 3.16 *** B | --- | 0.28 *** B |

| 10+ years in U.S. | --- | 1.25 B C | --- | 0.65 C |

| Non-Hispanics, 1.5 Generation | 0.74 B C | 0.75 B C | 1.21 C | 1.22 C |

| Pseudo R-square | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

Source and Sample: See Table 1.

The models control for individual characteristics and contextual factors (see text for details).

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

p<001 (significantly different from White natives)

p<.10

p<.05 (significantly different from Black natives)

p<.10

p<.05 (significantly different from 1.0 Generation; In models 2, the comparison group is the 1.0 generation with 0–4 years in U.S.)

In order to assess the second comparative hypothesis based on cultural repertoire ideas, we aggregate generational sub-groups for the three groups of immigrants and present odd-ratios from models regressing welfare behaviors on independent and controls variables in Table 3. The results indicate that other Hispanic and non-Hispanic immigrants (as well as native blacks) are more likely to receive AFDC than their native white counterparts, even after taking other factors into account. But Mexican immigrants do not differ significantly from native whites. In addition, non-Hispanic immigrants, but not Mexican and other Hispanic immigrants, are significantly less likely to exit AFDC than native whites, suggesting that non-Hispanic immigrants have longer welfare spells. Most critically for present purposes, however, Mexicans show a distinctive pattern compared to the other two immigrant groups and native blacks, one in which their welfare receipt and length of spells are not significantly different from those of native whites once other differences are controlled.

Table 3.

Odds Ratios for Nativity and Race/ethnicity from Models of AFDC recipiency, AFDC Exit, and Type of AFDC Exit†

| AFDC Recipiency | Exit From AFDC | Type of AFDC Exit

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emp. Exit vs. Staying on AFDC | Emp. Exit vs. Non-Emp. Exit | Non-Emp. Exit vs. Staying on AFDC | |||

| White Natives (ref) | |||||

| Black Natives | 5.29 *** C | 0.78 | 0.78 | 1.08 | 0.72 |

| Mexican Immigrants | 1.27 B | 0.99 | 1.93 | 2.88 | 0.67 |

| Non-Mexican Immigrants | --- | --- | 0.59 C | 1.52 | 0.39 ** B |

| Other Hispanic Immigrants | 3.24 *** B C | 0.65 | --- | --- | --- |

| Non-Hispanic Immigrants | 2.07 *** B c | 0.39 ** B C | --- | --- | --- |

| Pseudo R-square | 0.24 | 0.10 | 0.15 | ||

Source and Sample: See Table 1.

The models control for individual characteristics and contextual factors (see Table 2 for details).

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

p<001 (indicates significance of difference from White natives)

p<.10

p<.05 (significantly different from Black natives)

p<.10

p<.05 (significantly different from Mexican Immigrants)

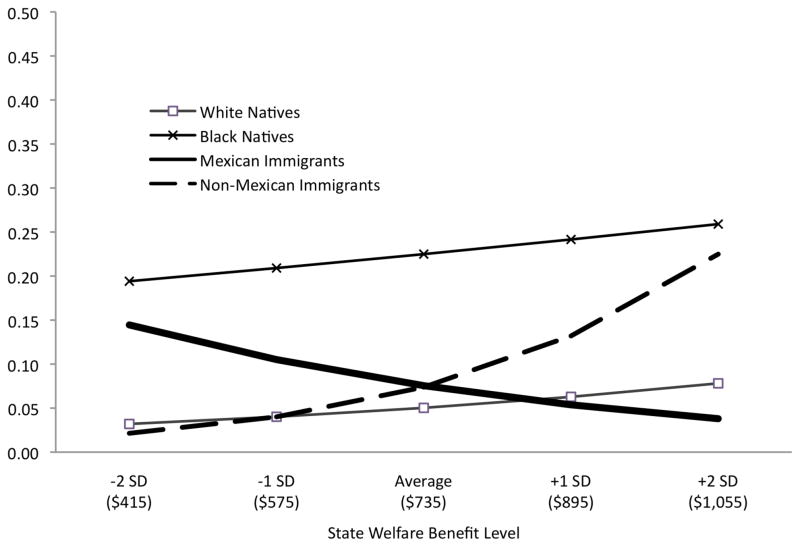

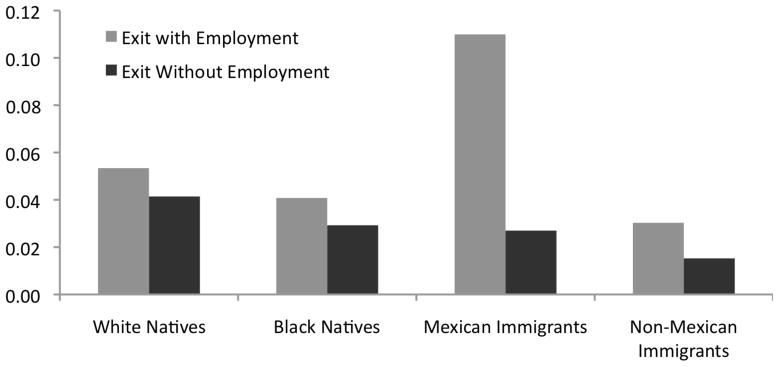

At this juncture, the findings provide tentative support for the second comparative cultural repertoire hypothesis in that they show lower receipt and shorter welfare spells for Mexicans than either of the other two immigrant groups, while at the same time indicating no statistically significant difference between Mexicans and native whites in these behaviors. For further assessment of the cultural repertoire idea, we now analyze welfare exits (Table 3). Here we see again that Mexicans do not differ from native whites, although other immigrants sometimes do (in these analyses we combine other Hispanic and non-Hispanic immigrants because we do not have enough cases to sub-divide into two groups given that the analyses subdivide those who exit welfare). Particularly in the critical employment exit columns (employment exit versus staying on AFDC and employment exit versus non-employment exit), the tendencies among Mexican immigrants are not significantly different from those of native whites, all else equal, although they exceed those of whites in both cases. The combined other immigrant group, however, shows some indication of being less likely than Mexican immigrants to leave welfare for work as opposed to staying on. To illustrate the size of these effects, we graphed the predicted percentages who leave welfare for employment versus other reasons (Figure 1). Mexican immigrant women clearly stand out as being more likely than the other groups to leave welfare for employment (a difference that turns out to be statistically significant). These results thus provide further support for the cultural repertoire hypothesis.

Figure 1.

Proportion Exiting Welfare with Employment and without Employment by nativity and race/ethnicity

Note: Estimates are predicted probabilities derived from the model of Type of AFDC exit in Table 3 (assuming native White means for all control variables)

Generosity of State Welfare Benefits

We next explore how welfare-related behaviors—receipt, welfare exit, and employment—are associated with state-level welfare policies in order to test the third main comparative hypothesis, one also generated from the cultural repertoire perspective. The hypothesis predicts that, in comparison to natives, immigrants would be less likely to receive welfare (because of shorter spells rather than fewer entries onto welfare) and more likely to transition from welfare to work when they reside in places providing greater economic support (i.e., in states with relatively generous welfare benefits). In the models whose results for immigrant and race groups were shown in Tables 2 and 3, results for state-welfare-benefit level were not shown in the tables. This variable was significantly positively associated with receiptvi and negatively associated with making a non-employment exit (compared with staying on welfare)vii. Thus our findings replicate prior research showing a positive association between welfare incentives (i.e., higher benefits) and welfare receipt.

In testing the third comparative hypothesis, however, we do not wish to constrain the effects of benefit level to be identical for all groups. We first assess whether the effects of benefit level vary among Mexicans, other immigrants, blacks, and whites by including interaction terms between the state-level indicator and racial/immigrant group status in the models. The results are shown in Table 4. The tests for interactions involving benefit level and group are significant for each of the three welfare behaviors (the coefficients for the interaction terms in these models are available to interested readers upon request). The tests indicate that the effects vary significantly across groups, although for some groups, such as native blacks, they do not differ significantly from native whites for any of the outcomes. We therefore focus here on the case of the immigrant groups, for which we graph predicted probabilities to help interpret results.

Table 4.

Effect (logged-odds) of State Benefit Level from Models of AFDC Recipiency and Type of AFDC Exit, by Nativity and Race/ethnicity

| Type of AFDC Exit

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFDC Recipiency | Emp. Exit vs. Staying on AFDC | Emp. Exit vs. Non-Emp. Exit | Non-Emp. Exit vs. Staying on AFDC | |

| White Natives | 0.15 * C | 0.14 | 0.42 B | −0.29 + |

| Black Natives | 0.06 C | −0.10 | −0.20 A C | 0.10 c |

| Mexican Immigrants | −0.23 * A B | 0.26 | 0.54 * B | −0.28 + b |

| Non-Mexican Immigrants | 0.40 *** A B C | −0.02 | 0.23 | −0.25 |

| Chi-square test for all interaction effects | p<.001 | p<.05 | ||

| Pseudo R-square | 0.26 | 0.20 | ||

Source and Sample: See Table 1.

Note: These models control for individual and contextual characteristics (see Table 2 for details). The models also include two-way interactions between nativity/race/ethnicity and state welfare benefit level. The estimates shown are the slopes of state benefit level by nativity/race/ethnicity (i.e., the main effect of state benefit level plus the interaction effect for each respective group).

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

p<001 (slope of state welfare guarantee is significantly different from zero)

p<.10

p<.05 (slope is significantly different from White natives)

p<.10

p<.05 (slope is significantly different from Black natives)

p<.10

p<.05 (slope is significantly different from Mexican Immigrants)

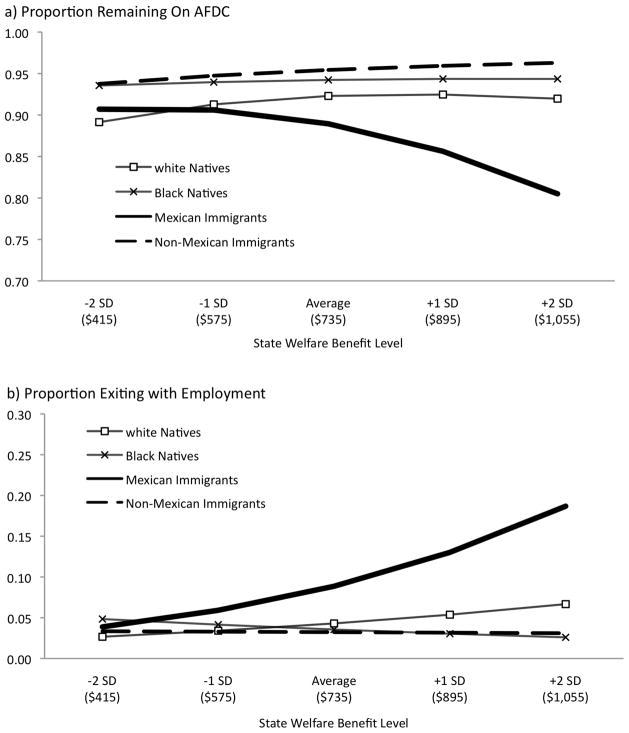

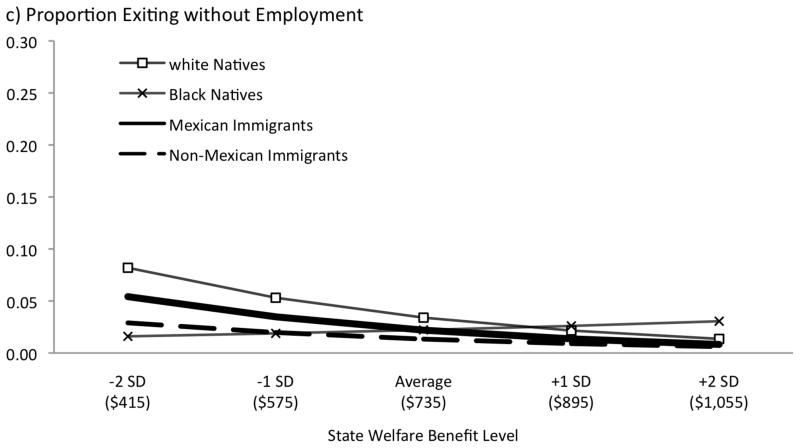

The findings concerning white natives are generally consistent with the expectations of economic choice theory. In this group, state welfare benefit level is significantly positively associated with welfare receipt (Figure 2) and negatively associated with making a non-employment exit from welfare (Figure 3c). Non-Mexican immigrants and black natives are similar in many respects in that the effect of welfare benefit level operates in the same direction on receipt as among white natives (although the effect is stronger for non-Mexican immigrants), and the effect on employment is not significantly different from white natives .

Figure 2.

Proportion Receiving AFDC by State Welfare Guarantee by Nativity and Race/Ethnicity

Note: Estimates are predicted probabilities of receiving AFDC derived from the model of AFDC recipiency in Table 4 (assuming native White means for all control variables)

Figure 3.

Proportion Remaining on AFDC, Exiting AFDC with Employment and Exiting AFDC without Employment, by State Welfare Benefit Level by Nativity and Race/Ethnicity

Note: Estimates are predicted probabilities derived from the model of AFDC exit in Table 4 (assuming native White means for all control variables)

But again the patterns for Mexicans are different, and as predicted, they are consistent with the cultural-repertoire hypothesis. Welfare receipt among Mexican immigrants is negatively associated with welfare benefit level, and falls below that for comparable white natives in states with higher welfare benefits, but is higher than that of white natives in states with lower welfare benefits (Figure 2). This pattern appears to be associated with shorter welfare spells and faster transitions to employment for Mexican immigrants in high benefit states rather than with Mexican immigrants being less likely to go on welfare in the first place. First, Mexican immigrants, unlike other groups, are more likely to transition from welfare to work in high benefit states compared with low benefit states (this is illustrated for Mexican immigrants in Figure 3b). Second, Mexican immigrants are more likely, not less likely, to start a welfare spell in higher benefit states. In a model predicting entry into AFDC (results not shown), we tested the same interaction between benefit level and group as we did for the receipt and exit models. State benefit level was significantly associated with going on AFDC for all groups; this effect was not significantly different for Mexican immigrants (and was even a bit more positive for Mexican immigrants than white natives although the difference was not significant). So in other words, welfare receipt is lower among Mexican immigrants living in a high-benefit state because the recipients in these states have shorter welfare spells, which is consistent with the idea that welfare itself may function as settlement assistance for Mexican immigrants. Overall, the effects of state welfare benefit level among Mexican immigrants operate in opposite directions from those predicted by economic choice theory and in directions expected by cultural repertoire theory.

Tests of Robustness

To assess the robustness of the findings, we re-ran the models several ways excluding different groups from the analysis, each time obtaining substantively consistent results (although significance levels tended to vary). We estimated models in which we restricted the sample to immigrants and natives with a high school degree or less, immigrants and natives who were single mothers at baseline, immigrants who had lived in the U.S. at least five years (to exclude the majority of illegal immigrants [(Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2004)]), immigrants who had naturalized (again, to exclude illegal immigrants), and immigrants and natives living in states other than California (because immigrants’ welfare recipiency dropped more following Welfare Reform in California than in other states (Borjas 2001)).

We also explored the possibility of selective migration bias. If states with generous welfare programs also have stronger economies (in our data, the correlation between state unemployment rate and welfare benefit level is 0.39), then this might explain immigrants’ relatively favorable outcomes in higher benefit states. We attempted to reduce any effects of such selection by re-running the models on a restricted sample of inter-state movers. We identified all foreign born and native women who live in a different state from their state of birth as inter-state movers. Our logic was that the foreign born would be selected into certain states by the same types of factors (related to welfare benefits and economic factors) as would native-born inter-state movers. If selection bias were operating in the same way for immigrants as natives, then the bias should be canceled out in analyses that compare immigrants with native-born inter-state movers. The results were nearly identical to the models that included all natives, suggesting that our findings are not significantly affected by migration selection bias. Finally, we estimated the recipiency models with state-fixed effects (possible because the sample includes multiple observations per person and state welfare benefit level changed somewhat during the time period in several states). Although the standard errors for welfare benefit increased in the state-fixed-effects models (which we expected given that the variance of benefit level across states is greater than the variance within states over time), the coefficients for all the major variables (welfare benefit level, group, and the interaction of benefit and group) remained the same and highly significant.

Discussion and Conclusions

The present research generates findings that suggest the importance of moving beyond existing theoretical explanations of welfare receipt to consider the influence of cultural repertoires that may often help account for group-specific patterns of behavior. While considerable evidence suggests that the forces emphasized by rational choice and social structural disadvantage theories constitute major factors affecting patterns of welfare receipt, these approaches have never proven entirely satisfactory for accounting for why poor immigrants, especially poor Mexicans, are less likely to participate in welfare than poor natives. Culture of poverty explanations fare little better because they fail to predict the declines in immigrant public assistance receipt, all else equal, that typically occur among immigrants the longer they live in the country. If greater duration of residence led to greater welfare acculturation among immigrants and involved an increasing tendency to embrace the values and orientations of those mired in poverty (at least in the case of poor immigrants), one would expect just the opposite. Hence, conventional theoretical approaches, while fruitful in many instances, have not proven applicable to all groups of recipients, particularly Mexican immigrants.

Here we present alternative ideas about employment-based cultural repertoires among Mexican immigrants to help explain their welfare behaviors. This perspective suggests that the unauthorized labor migration undertaken by most Mexicans, as well as the working-class nature of their employment in the country, shape cultural repertoires about work in ways that influence welfare behaviors, leading to lower receipt and higher post-welfare employment among Mexican immigrants. Further, we not only find empirical evidence for this, we also observe that such tendencies, especially the inclination to exit welfare for employment, are most likely to occur under welfare policy contexts offering the greatest degree of public assistance. This provides particularly strong support for the employment-related cultural repertoire hypothesis. As a consequence, the research results presented here illustrate the importance of taking cultural considerations into account in explaining distinctive Mexican immigrant welfare behaviors. The strong involvement of work and family in the Mexican decision to migrate continues to establish and order priorities for maintaining employment well after the migration takes place, operating in effect to minimize welfare receipt and increase post-welfare employment.

This new understanding of the kinds of factors that drive immigrant welfare recipiency carries important policy implications. Immigrant welfare receipt has fueled debates about U.S. immigration and welfare policy for a century or more. A common perception has been that immigrants should not receive public assistance (Edwards 2001). As early as 1891, U.S. immigration law permitted immigrants who became “public charges” to be deported. The present paper critically evaluates such negative characterizations of immigrant public assistance recipiency, especially in the Mexican case. First, we find no evidence in support of the culture of poverty perspective. Immigrant welfare recipiency, retention, and lower post-welfare employment levels tend to be concentrated among newly-arrived immigrants and, for those immigrating as young children as opposed to older ages, they tend not to be significantly different from those of natives. Welfare receipt thus does not appear to constitute a permanent way of life for most immigrants during the pre-reform period when immigrants were still eligible to receive welfare. Also, prior research has shown that immigrants tend to settle in higher-benefit states, a finding that at first glance appears to support the view that welfare acts as magnet for immigrants. But we find that Mexican immigrants are less likely to receive welfare in higher benefit states compared with those in lower benefit states, thus calling into question the “magnet” hypothesis.

The results further suggest that public assistance may in fact exert a positive effect on integration, functioning perhaps at times as a surrogate for settlement assistance, or at least as a way to help immigrants work their way out of poverty and off welfare. Mexican immigrants leaving welfare are more likely to be employed in states with more generous welfare programs than in states with less generous welfare programs. Such a finding is consistent with the employment-related cultural repertoire perspective, and points to the possibility that the circumstances leading Mexican immigrants to welfare are different and more temporary than those that often lead natives to welfare. For example, accounts of working poor natives characterize welfare recipients and former welfare recipients as sometimes fearful of leaving their neighborhoods to search for work or seek out new experiences (Shipler 2004). Further, welfare recipients and former recipients often are so disadvantaged that they lack the “soft skills” necessary to obtain and keep a job. Mexican immigrants, on the other hand, especially female labor migrants, often seem to be characterized by unusually high levels of initiative and industriousness (Bean et al. 2001; Ruiz 1998). Their reasons for seeking welfare thus appear different. They may participate in public assistance simply because, as newcomers, they are unfamiliar with the labor market, do not have well-developed non-familial social networks, and have less control over or ability to alter their circumstances in the United States. Unlike many of the reasons of severe disadvantage that incline (even necessitate) natives to participate in welfare, such factors may fade with time for immigrants.

Overall, while native pre-reform welfare recipiency may often have derived either from convenience or from persistent social structural difficulties that leave an extremely disadvantaged group in dire need of help, immigrant welfare recipiency may be more likely to arise from temporary employment challenges associated with the fact that immigrants are societal newcomers. In higher benefit states, the additional material resources provided by welfare appear to help Mexican immigrants overcome such challenges. These findings raise serious concerns about U.S. policies (or the lack thereof) with respect to immigrant settlement and integration. Welfare reform appears to have been formulated under the assumption that the factors leading to welfare recipiency among immigrants are the same as they are for disadvantaged natives, especially blacks. If policy makers and analysts have been misguided in assuming that immigrants are drawn to the United States by welfare, or that immigrants “assimilate” into welfare, then welfare reform as it is implemented in the Mexican immigrant case is not likely to deter future immigration. Even worse, it may actually operate to delay economic incorporation (particularly if no other form of economic settlement assistance becomes available to immigrants under conditions of great economic need).

More generally, the welfare and work behaviors among Mexican immigrants appear consistent with a theoretical logic that suggests strong work orientations predominate over choice mechanisms and culture of poverty factors in affecting welfare participation. This suggests that settlement assistance to immigrants, especially Mexican immigrants and others with strong pro-work orientations and employment tendencies, would indeed provide stop-gap help between employment stints rather than hand-outs fostering disincentives to work or payments constituting invitations to dependency. Such a buttressing of immigrant employment would reinforce the potentially positive integration benefits (e.g., immigrant poverty reduction) that would accrue were the United States to adopt settlement policies that facilitated the economic incorporation of low-skilled labor immigrants.

Acknowledgments

The research reported here was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01-HD-39075), in part by the Center for Research on Immigration, Population, and Public Policy at the University of California, Irvine and in part by the Population Research Institute at the Pennsylvania State University through core funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Earlier versions of the paper were presented at the 2006 annual meetings of the Population Association of America and at the Russell Sage Foundation Symposium on Immigrant Children and Families on the 10th Anniversary of Welfare Reform, held at the Migration Policy Institute, Washington, DC, on December 15, 2007. We also express our thanks to James Bachmeier, Susan K. Brown, Calvin Morrill, David Neumark, Joy Pixley, Francisca Polletta, and Rosaura Tafoya-Estrada, all of whom provided helpful comments about the research and/or paper. Please direct all questions to Jennifer Van Hook (jvanhook@pop.psu.edu). We are happy to provide assistance to researchers who are interested in replicating the findings presented here.

Biographies

Jennifer Van Hook is Associate Professor of Sociology and Demography at the Pennsylvania State University. She examines the integration of U.S. immigrants and their children, focusing in particular on the relationship between the social, economic, and policy contexts of reception and the incorporation patterns of immigrants and their children. Although much of her work has focused on immigrant welfare behaviors, she has also published extensively on a wide range of other social and economic domains, such as poverty and household/family structure. Much of her recent work has focused on the health and well-being of the children of immigrants.

Frank D. Bean is Chancellor’s Professor School of Social Sciences and Director of the Center for Research on Immigration, Population and Public Policy at the University of California at Irvine. His current research focuses on the implications of U.S. immigration policies, Mexican immigrant incorporation, the implications of immigration for changing race/ethnicity in the United States, the determinants and health consequences of immigrant naturalization, and the development of new estimates of unauthorized immigration and emigration. Among his many publications is America’s Newcomers and the Dynamics of Diversity (2003) (co-authored with Gillian Stevens).

Footnotes

Our approach overlaps to some degree with social psychological expectancy theory (Atkinson, John W. 1964. An Introduction to Motivation. Princeton: D. Van Nostrand, Fishbein, Martin and I. Ajzen. 1975. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.), which suggests that expectations about success in the labor market influence welfare behaviors (Bane and Elwood 1994). But expectancy theory does not root such work expectations in the historical and socioeconomic circumstances of groups, whereas, following Lamont (1992; 2000), cultural repertoire approaches do. Thus, conceptualizing cultural orientations in materialist-based repertoire terms provides a more comprehensive theoretical perspective about the origins of cultural expectations than does one that envisions expectations in social psychological terms that take the origins of such expectations for granted.

These countries are the former Soviet Union, Cuba, Vietnam, Laos, Romania, Iran, Ethiopia, Cambodia, Poland, Afghanistan, and Nicaragua. In the case of persons coming during the 1990s, countries from the Balkans are added to this list. The eleven “refugee-sending” countries sent almost 90 percent of all refugee arrivals to the United States during the 1980s, and over 91 percent of the persons they supplied came as refugees (Bean, Stevens, and Van Hook 2003).

Duration of the welfare spell is a time-varying indicator measured at the time of each interview (for those currently on welfare, duration = date of interview – date of start of welfare spell). The estimate of duration includes portions of the welfare spell that occurred prior to the first SIPP panel (based on retrospective reports of the timing of the beginning of welfare spells). 14 percent of respondents reported having been on welfare before their first birth or before they had come to live in the U.S., so corrective adjustments were made in the baseline duration for these cases.

We used the Kaplan-Meier estimation method to evaluate the survival function of the duration of welfare spells for immigrant and native women. This method appropriately handles right and left censoring. This and all other analyses were conducted using STATA statistical software.

For example, if a person were on AFDC, but then dropped out after the 4th interview without having first exited welfare, we code this person as censored as of the time of the 5th interview.

Odds ratio = 1.21, p < .001, indicating a 21% increase in the likelihood of AFDC recipiency for a $100 increase in state welfare benefit.

Odds ratio = 0.78, p < .10, indicating a 22% decrease in the likelihood of making a non-employment exit (vs. staying on AFDC) for a $100 increase in state welfare benefit.

Contributor Information

Jennifer Van Hook, Pennsylvania State University.

Frank D. Bean, University of California, Irvinen

References

- Allison Paul D. Event History Analysis: Regression for Longitudinal Event Data. Newbury Park, CA: Russell Sage Foundation; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ashenfelter Orley. Determining Participation in Income-tested Social Programs. Journal of American Statistical Association. 1983;78:517–525. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson John W. An Introduction to Motivation. Princeton: D. Van Nostrand; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Auletta Ken. The Underclass. New York: Random House; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bane Mary Jo, Ellwood David T. Welfare Realities. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bean Frank D, Feliciano Cynthia, Lee Jennifer, VanHook Jennifer. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2009. The New U.S. Immigrants: What They Mean for Race in the 21st Century. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean Frank D, Baker Susan Gonzalez, Capps Randy. Immigration and Labor Markets in the United States. In: Berg I, Kalleberg A, editors. Sourcebook on Labor Markets: Evolving Structures and Processes. New York: Plenum Press; 2001. pp. 669–703. [Google Scholar]

- Bean Frank D, Stevens Gillian. America’s newcomers and the dynamics of diversity. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bean Frank D, Stevens Gillian, Van Hook Jennifer. Immigration and Immigrant Welfare Receipt. In: Bean FD, Stevens G, editors. Americas Newcomers and the Dynamics of Diversity. New York: Russell Sage and ASA Arnold Rose Monograph Series; 2003. pp. 66–93. [Google Scholar]

- Bean Frank D, Van Hook Jennifer VW, Glick Jennifer E. Country-of-Origin, Type of Public Assistance and Patterns of Welfare Recipiency among U.S. Immigrants and Natives. Social Science Quarterly. 1997;78:432–451. [Google Scholar]

- Binder Amy, Blair-Loy Mary, Evans John, Ng Kwai, Schudson Michael. Introduction: The Diversity of Culture. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2008;619:6–14. [Google Scholar]

- Blank Rebecca, Haskins Ron. The New World of Welfare. Washington: The Brookings Institution; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Blau Francine. The Use of Transfer Payments by Immigrants. Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 1984;37:222–239. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas George J. Friends or Strangers: The Impact of Immigrants on the US Economy. New York: Basic Books; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas George J. Immigration and Welfare: a Review of the Evidence. In: Duignan P, Gann H, editors. The Debate in the United States over Immigration. Stanford: Hoover Institute Press; 1998. pp. 121–144. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas George J. Immigration and Welfare Magnets. Journal of Labor Economics. 1999;17:607–37. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas George J. Welfare Reform and Immigration. In: Bland R, Haskins R, editors. The New World of Welfare. Washington, DC: Brookings Institute Press; 2001. pp. 369–385. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas George J, Hilton Lynette. Immigration and the Welfare State: Immigrant Participation in Means-Tested Entitlement Programs. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1996:575–604. [Google Scholar]

- Burtless Gary. The Economist’s Lament: Public Assistance in America. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1990;4:57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Butler Amy C. The Effect of Welfare Benefit Levels on Poverty Among Single-Parent Families. Social Problems. 1996;43:94–115. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarty Rameswar P. Multivariate Analysis by Users of SIPP Micro-Data Files. U. S. Bureau of the Census; Washington, DC: 1989. [Google Scholar]