Abstract

Introduction

This study compared the number of, and expenditures on, first-line intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) injections between patients who were treated with aflibercept or ranibizumab for wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study based on U.S. administrative claims data. Selected patients had initiated first-line intravitreal anti-VEGF treatment with ranibizumab or aflibercept (index date) between November 18, 2011 and April 30, 2013, were aged ≥18 years on the index date, had 12 months of continuous insurance enrollment prior to the index date (baseline period), were diagnosed with wet AMD during the baseline period or on the index date, and had at least 6 or 12 months of follow-up enrollment after the index date without switching to a different anti-VEGF agent (follow-up periods). Outcomes measured within the 6 and 12 month follow-up periods included the number of, and healthcare expenditures on, intravitreal anti-VEGF injections. Multivariable regressions compared the outcomes between aflibercept and ranibizumab.

Results

The 6 months analyses included 319 aflibercept patients and 1,054 ranibizumab patients (12 month analyses: 57 and 374, respectively). Over the first 6 months after the index date, neither the number of injections (aflibercept mean = 3.8 ± 1.6; ranibizumab mean = 3.9 ± 1.9) nor the expenditures on injections (aflibercept mean = $7 468 ± $4 211; ranibizumab mean = $7 816 ± $4 834) differed significantly between aflibercept patients and ranibizumab patients (in multivariable regression treating ranibizumab as reference: incidence rate ratio = 0.97, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.91–1.03, P = 0.277; cost ratio = 0.96, 95% CI 0.89–1.04, P = 0.338). Differences were also insignificant in the 12 month analyses. The overall mean days between injections differed by only 1.8 (95% CI 1.3–2.3) days between the aflibercept patients and ranibizumab patients (42.4 and 40.6, respectively).

Conclusion

Aflibercept and ranibizumab were used at a similar frequency resulting in similar intravitreal anti-VEGF injection healthcare expenditures among wet AMD patients initiating first-line intravitreal anti-VEGF treatment.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-013-0078-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor, Healthcare expenditures, Healthcare utilization, Intravitreal, Ophthalmology, Retrospective wet age-related macular degeneration

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is an eye condition that causes destruction of the macula, leading to losses of vision that can be severe enough as to constitute legal blindness [1]. Prior to the advent of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) therapy, AMD was the most common cause of vision loss among individuals in the United States, with a prevalence of 6.5% among people aged 40 years and older [1, 2]. AMD can be either non-exudative (atrophic or dry) or exudative (neovascular or wet). Dry AMD accounts for 90% of U.S. AMD cases, is associated with sequelae that in most cases are comparatively less severe than those seen in wet AMD, and is generally managed through observation with no medical or surgical therapies and/or antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements [3, 4]. In contrast, wet AMD causes the great majority of severe vision loss and legal blindness, and is managed through a variety of treatment modalities including photodynamic therapy, laser surgery, and intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF agents [4, 5]. Anti-VEGF therapy has now become the standard of care for treating wet AMD disease.

Currently, there are three intravitreal anti-VEGF treatments approved by U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of wet AMD: pegaptanib (approved 2004), ranibizumab (approved 2006), and aflibercept (approved 2011) [6–8]. Bevacizumab is not approved by the FDA for the treatment of wet AMD, but is nevertheless used for this purpose off-label. Among the three FDA-approved intravitreal anti-VEGF treatments, ranibizumab and aflibercept are the most commonly used agents, while pegaptanib is rarely used.

Based on findings from the HARBOR study (The pHase III, double-masked, multicenter, randomized, Active treatment-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of 0.5 and 2.0 mg Ranibizumab administered monthly or on an as-needed Basis (PRN) in patients with subfoveal neovascular AMD study), the package insert for ranibizumab was recently expanded to include less-than-monthly dosage and administration options after 3 initial monthly doses in addition to the originally recommended once-monthly frequency [9]. Although the ranibizumab 0.5 mg PRN regimen did not meet the non-inferiority endpoint compared to the ranibizumab 0.5 mg monthly regimen at 12 months in the HARBOR study, it still led to rapid, sustained and clinically meaningful vision gains out to 24 months (9.1 letters for the monthly regimen and 7.9 letters for the PRN regimen). The package insert recommended dosage and administration for aflibercept is once monthly for the first three months followed by once every other month, although dosing as frequently as monthly is an alternative regimen.

The potential for less frequent injections of aflibercept and ranibizumab, which could translate to fewer physician visits and lower cost of anti-VEGF treatment, is appealing to patients and payers alike. However, the use of treatments in ‘real world’ clinical practice may be different from what is stipulated in the package inserts. Thus, the aim of this study is to examine first-line intravitreal anti-VEGF treatment patterns in wet AMD patients, specifically comparing the number of, and expenditures on, intravitreal anti-VEGF injections between patients who are treated with aflibercept or ranibizumab.

Materials and Methods

Data Source

This study’s data source was U.S. health insurance claims data extracted from the Truven Health MarketScan® Commercial Claims and Encounters (Commercial) and Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits (Medicare Supplemental) databases (Truven Health Analytics, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). These databases represent a non-probability sample and comprise inpatient and outpatient medical and outpatient prescription drug claims for over 40 million (annually) employees, dependents, and retirees with employer-sponsored primary or Medicare supplemental insurance.

The Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases are derived from large self-insured employers and health plans, including a variety of prescription drugs and medical insurance arrangements. Information on payments from both Medicare and Medicare supplemental health insurance plans is included within the Medicare Supplemental database.

The data contained in these databases are statistically de-identified and have been certified to satisfy the conditions set forth in Sections 164.514 (a)-(b)1ii of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. As such, Institutional Review Board approval and written informed consent were not sought for this study.

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Sample Selection Criteria

This study sought to select patients initiating first-line intravitreal anti-VEGF treatment with aflibercept or ranibizumab for wet AMD between November 18, 2011 (the U.S. FDA approval date for aflibercept) and April 30, 2013 (the last date for which data were available at the time that this study was conducted). Although this study focused specifically on aflibercept and ranibizumab, it was necessary to track instances of treatment with pegaptanib or bevacizumab to appropriately determine that patients were indeed initiating first-line anti-VEGF therapy and to identify whether a patient had switched to a different anti-VEGF therapy after initiation. Accordingly, patients selected for study were required to meet all of the following sample selection criteria: evidence of intravitreal treatment with aflibercept, ranibizumab, pegaptanib, or bevacizumab between January 1, 2006 and April 30, 2013, as identified through the administrative claims-based algorithm described in Appendix A (the date of the first observed intravitreal treatment was designated the index date and the anti-VEGF to which the index date corresponded was designated the index anti-VEGF); at least 12 months of continuous medical and prescription insurance enrollment prior to the index date (the 12-month period prior to the index date was designated the baseline period); at least one inpatient or non-diagnostic outpatient medical claim with a diagnosis of wet AMD (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] 362.52) [10], in any diagnosis position, incurred during the baseline period or on the index date; 18 years of age or older on the index date; no evidence of intravitreal treatment with ranibizumab, aflibercept, pegaptanib, or bevacizumab during the baseline period (serving as a ‘clean’ period to establish that patients were initiating first-line anti-VEGF treatment). This study focused primarily on patients initiating first-line anti-VEGF treatment between November 18, 2011 and April 30, 2013; however, a sensitivity analysis was also conducted in which patients who had initiated ranibizumab prior to the aflibercept approval date of November 18, 2011—as early as June 30, 2006—were included for analysis.

In an attempt to generate results that were reflective of the variety of ways in which intravitreal anti-VEGF therapies may be prescribed, all patients meeting the criteria above were included for study, irrespective of the potential treatment strategy that a physician may have been using for a given patient (e.g., monthly, PRN, or treat and extend).

Follow-up Period and Outcomes

For each patient, a follow-up period was established that extended from their index date until the first occurrence of one of the following events: switch to a different anti-VEGF agent, disenrollment from health insurance, inpatient death, or reaching April 30, 2013. This study focused on two patient samples, those with follow-up periods that lasted 6 months or longer and those with follow-up periods that lasted 12 months or longer.

The primary outcomes were measured within the first 6 months and first 12 months of the follow-up period and included the number of intravitreal anti-VEGF injections and healthcare expenditures on intravitreal anti-VEGF injections. The days elapsed between each intravitreal anti-VEGF injection were also calculated. Healthcare expenditures were measured using the financial fields on administrative claims in the MarketScan Databases and included the gross covered payments for the anti-VEGF agent alone (i.e., not including the payments associated with intravitreal administration procedure), which includes deductibles, copayments, coordination of benefits and the amount eligible for payment after applying pricing guidelines such as fee schedules and discounts.

A secondary outcome—days between intravitreal anti-VEGF injections—was examined in a supplementary analysis. For this analysis, all patients who met the study inclusion criteria, except those related to minimum durations of follow-up were included in an effort to increase sample sizes. That is, all patients with 2 or more injections were used to calculate the mean days between the first and second injections, all patients with 3 or more injections were used to calculate the mean days between the second and third injections, and so on, regardless of having 6 months or 12 months of follow-up.

Covariates

Several covariates, including demographics and clinical characteristics that are potentially relevant to AMD and the use of intravitreal anti-VEGF therapies, were measured throughout the baseline period to describe the study sample and to be used in the multivariable models described below. Demographics were measured on the index date and included patient age in years, sex, U.S. Census Bureau geographic region of residence, insurance plan type, urban residence (based on residence in a Metropolitan Statistical Area), and—as a proxy for socioeconomic status—the median household income in the zip code (using first 3 digits only) in which the patient’s residence was located. Clinical characteristics were measured throughout the baseline period and included indicators for comorbidities (non-melanoma cancer, dyslipidemia, retinal vein occlusion, diabetic macular edema, cataracts and glaucoma), indicators for treatments (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticoids, photodynamic therapy, laser photocoagulation therapy, cataract surgery, and intravitreal steroid injection), and indices of general health status (Deyo-Charlson comorbidity index, number of unique ICD-9-CM diagnoses, number of unique National Drug Codes, and total all-cause healthcare expenditures) [11]. The codes and specific criteria used to measure the covariates are described in Appendix B.

Statistical Analyses

Bivariate descriptive summary statistics were used to display the study outcomes, stratified by index anti-VEGF (aflibercept or ranibizumab). Multivariable Poisson quasi-likelihood regressions were used to compare the number of intravitreal anti-VEGF injections between aflibercept and ranibizumab patients, adjusting for an a priori specification of all measured patient demographics and clinical characteristics. To handle over-dispersion in the outcome distribution, a scale parameter, estimated by the square root of deviance divided by degrees of freedom, was used to adjust the regression. Multivariable generalized linear models (GLMs) using a log link and Gamma error distribution, which was chosen to account for the non-normality of the expenditure data distribution, were used to compare the total expenditures on intravitreal anti-VEGF injections between aflibercept and ranibizumab patients, adjusting for an a priori specification of all measured patient demographics and clinical characteristics. Statistical Analysis Software (SAS®) 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used to conduct the analyses. An alpha value of 0.05 was set as the a priori threshold for statistical significance on inference related to the study analyses.

Results

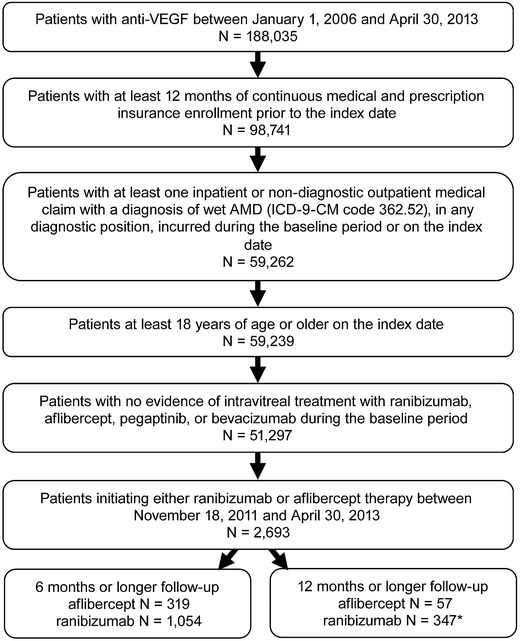

Figure 1 displays the sample attrition associated with the application of each sample selection criterion. Ultimately, the sample of patients initiating first-line anti-VEGF therapy included 319 aflibercept patients and 1,054 ranibizumab patients with at least 6 months of follow-up (57 and 374 in 12 month analyses, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Sample selection attrition. AMD age-related macular degeneration, ICD-9-CM International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor. *Patients who had initiated ranibizumab prior to the aflibercept approval date of November 18, 2011 (N = 8,519) for sensitivity analyses

Tables 1 and 2 display patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics, respectively. Across the aflibercept and ranibizumab patients and in both follow-up samples, mean age differed by less than 1 year (approximately 78–79 years) and the proportion of females was slightly over one-half. When examining the most prevalent comorbidities (e.g., dyslipidemia), aflibercept patients generally did not differ substantially from ranibizumab patients. Mean values for the indices of general health status (e.g., Deyo-Charlson comorbidity index) were also generally similar, with slightly higher values (being indicative of poorer health) in the ranibizumab patients.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| 6 Month analyses | 12 Month analyses | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ranibizumab patients | Aflibercept patients | Ranibizumab patients | Aflibercept patients | |||||

| N | 1,054 | N | 319 | N | 374 | N | 57 | |

| Age (mean, SD) | 79.3 | 10.3 | 79.6 | 9.1 | 79.1 | 10.1 | 78.4 | 11.1 |

| Age group (N, %) | ||||||||

| 18–24 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| 25–34 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| 35–44 | 4 | 0.4% | 1 | 0.3% | 2 | 0.5% | 1 | 1.8% |

| 45–54 | 30 | 2.8% | 1 | 0.3% | 8 | 2.1% | 1 | 1.8% |

| 55–64 | 73 | 6.9% | 24 | 7.5% | 24 | 6.4% | 5 | 8.8% |

| 65–74 | 164 | 15.6% | 54 | 16.9% | 64 | 17.1% | 8 | 14.0% |

| 75+ | 783 | 74.3% | 239 | 74.9% | 276 | 73.8% | 42 | 73.7% |

| Sex (N, %) | ||||||||

| Male | 430 | 40.8% | 143 | 44.8% | 166 | 44.4% | 24 | 42.1% |

| Female | 624 | 59.2% | 176 | 55.2% | 208 | 55.6% | 33 | 57.9% |

| Index year (N, %) | ||||||||

| 2011 | 141 | 13.4% | 9 | 2.8%a | 118 | 31.6% | 8 | 14.0%a |

| 2012 | 913 | 86.6% | 310 | 97.2% | 256 | 68.4% | 49 | 86.0% |

| Geographic region (N, %) | ||||||||

| Northeast | 219 | 20.8% | 78 | 24.5% | 79 | 21.1% | 18 | 31.6% |

| North Central | 352 | 33.4% | 100 | 31.3% | 119 | 31.8% | 20 | 35.1% |

| South | 326 | 30.9% | 95 | 29.8% | 123 | 32.9% | 14 | 24.6% |

| West | 148 | 14.0% | 46 | 14.4% | 52 | 13.9% | 5 | 8.8% |

| Unknown | 9 | 0.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Population density (N, %) | ||||||||

| Urban | 913 | 86.6% | 272 | 85.3% | 331 | 88.5% | 51 | 89.5% |

| Rural | 132 | 12.5% | 47 | 14.7% | 42 | 11.2% | 6 | 10.5% |

| Unknown | 9 | 0.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Health plan type2 (N, %) | ||||||||

| FFS | 549 | 52.1% | 177 | 55.5% | 217 | 58.0% | 31 | 54.4% |

| HMO | 77 | 7.3% | 29 | 9.1% | 23 | 6.1% | 3 | 5.3% |

| POS | 43 | 4.1% | 13 | 4.1% | 13 | 3.5% | 6 | 10.5% |

| PPO | 350 | 33.2% | 90 | 28.2% | 115 | 30.7% | 16 | 28.1% |

| Other | 35 | 3.3% | 10 | 3.1% | 6 | 1.6% | 1 | 1.8% |

| Primary Payer Type (N, %) | ||||||||

| Commercial | 105 | 10.0% | 25 | 7.8% | 33 | 8.8% | 7 | 12.3% |

| Medicare | 949 | 90.0% | 294 | 92.2% | 341 | 91.2% | 50 | 87.7% |

| Median household income (Mean, SD)b | $50,835 | $17,535 | $49,710 | $16,804 | $50,536 | $16,455 | $50,614 | $18,619 |

FFS fee-for-service, HMO health maintenance organization, POS point-of-service, PPO preferred provider organization

aDenotes a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) between ranibizumab patients and aflibercept patients; for categorical variables, one “*” is reported in first row

bMedian household income was only recorded on patient’s index date, not at the index dates of each exposure

Table 2.

Patient clinical characteristics

| 6 Month analyses | 12 Month analyses | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ranibizumab patients | Aflibercept patients | Ranibizumab patients | Aflibercept patients | |||||

| N | 1,054 | N | 319 | N | 374 | N | 57 | |

| Comorbidities (N, %) | ||||||||

| Non-melanoma cancer | 123 | 11.7% | 36 | 11.3% | 38 | 10.2% | 8 | 14.0% |

| Dyslipidemia | 657 | 62.3% | 202 | 63.3% | 224 | 59.9% | 35 | 61.4% |

| Retinal vein occlusion | 25 | 2.4% | 2 | 0.6%a | 10 | 2.7% | 1 | 1.8% |

| Diabetic macular edema | 57 | 5.4% | 11 | 3.4% | 17 | 4.5% | 1 | 1.8% |

| Cataracts | 309 | 29.3% | 107 | 33.5% | 101 | 27.0% | 17 | 29.8% |

| Glaucoma | 216 | 20.5% | 63 | 19.7% | 81 | 21.7% | 13 | 22.8% |

| Treatments (N, %) | ||||||||

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 115 | 10.9% | 30 | 9.4% | 44 | 11.8% | 6 | 10.5% |

| Glucocorticoids | 126 | 12.0% | 35 | 11.0% | 38 | 10.2% | 4 | 7.0% |

| Photodynamic therapy | 7 | 0.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.5% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Laser photocoagulation therapy | 5 | 0.5% | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Cataract surgery | 119 | 11.3% | 40 | 12.5% | 44 | 11.8% | 8 | 14.0% |

| Intravitreal steroid injection | 171 | 16.2% | 62 | 19.4% | 46 | 12.3% | 2 | 3.5%a |

| Indices of general health status (Mean, SD) | ||||||||

| Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.5 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 1.6a | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.5 |

| Unique 3-digit ICD-9-CM diagnoses | 14.4 | 9.9 | 12.7 | 8.1a | 13.7 | 9.6 | 12.7 | 7.0 |

| Unique National Drug Codes | 12.0 | 8.6 | 10.7 | 7.6a | 11.2 | 8.8 | 11.5 | 7.4 |

| Baseline total healthcare expenditures | $17,307 | 36,674 | $13,293 | 25,345 | $14,241 | 25,789 | $19,484 | 48,976 |

| Median | $7,413 | $6,909 | $6,676 | $7,041 | ||||

ICD-9-CM International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical modification

aDenotes a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) between ranibizumab patients and aflibercept patients

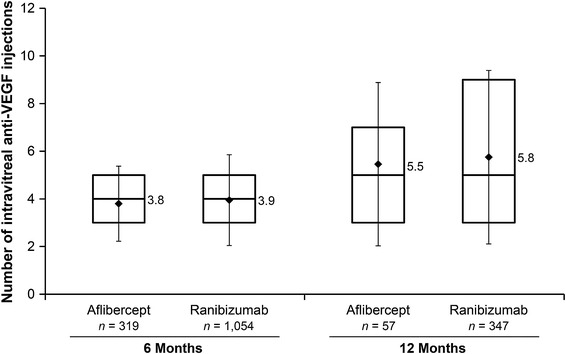

Figure 2 displays the unadjusted number of intravitreal anti-VEGF injections over the first 6 and 12 months after the index date. In the 6 month analyses, the mean number of injections was 3.8 in the aflibercept patients and 3.9 in the ranibizumab patients. Multivariable regression adjusting for patient demographics and clinical characteristics determined that the number of injections did not differ in a statistically significant manner between aflibercept patients and ranibizumab patients (Table 3: incidence rate ratio [IRR] treating ranibizumab as reference category = 0.97, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.91–1.03, P = 0.277). Factors that were significantly associated with receiving fewer intravitreal anti-VEGF injections included being a member of a Health Maintenance Organization (vs. fee-for-service) (IRR = 0.80, 95% CI 0.72–0.90, P < 0.001) and having baseline treatment with intravitreal steroid injection (IRR = 0.92, 95% CI 0.85–0.98, P = 0.015). Factors that were significantly associated with receiving more intravitreal anti-VEGF injections included being aged 75–84 (vs. 85+) years (IRR = 1.07, 95% CI 1.00–1.13, P = 0.035) and having baseline treatment with non-intravitreal glucocorticoids (IRR = 1.14, 95% CI 1.05–1.24, P = 0.002). In the 12 month analyses, the mean number of injections was 5.5 in the aflibercept patients and 5.8 in the ranibizumab patients. Again, the number of injections did not differ in a statistically significant manner between aflibercept patients and ranibizumab patients (Table 3: IRR treating ranibizumab as reference category = 0.95, 95% CI 0.79–1.14, P = 0.582).

Fig. 2.

Number of intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) injections over the first 6 months (left bars) and 12 months (right bars) after the index date. *The boxes represent the 25th percentile (bottom of box), median (line in center of box), and 75th percentile (top of box); the diamonds are means with error bars representing the standard deviation

Table 3.

Multivariable Poisson quasi-likelihood regression of number of intravitreal anti-VEGF injections over the first 6 and 12 months after the index date

| Parameter | 6 Month analyses | 12 Month analyses | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence rate ratio | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P | Incidence rate ratio | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P | |

| Aflibercept (reference = ranibizumab) | 0.97 | 0.91 | 1.03 | 0.277 | 0.95 | 0.79 | 1.14 | 0.582 |

| Age 18–64 years (reference = 85 + years) | 0.96 | 0.86 | 1.06 | 0.405 | 0.85 | 0.66 | 1.11 | 0.235 |

| Age 65–74 years (reference = 85 + years) | 1.07 | 0.99 | 1.16 | 0.088 | 1.04 | 0.86 | 1.26 | 0.665 |

| Age 75–84 years (reference = 85 + years) | 1.07 | 1.00 | 1.13 | 0.035 | 1.02 | 0.88 | 1.18 | 0.791 |

| Male (reference = female) | 0.98 | 0.93 | 1.04 | 0.497 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 1.11 | 0.749 |

| Region: North Central (reference = Northeast) | 1.01 | 0.94 | 1.09 | 0.761 | 0.94 | 0.79 | 1.13 | 0.543 |

| Region: South (reference = Northeast) | 1.06 | 0.99 | 1.15 | 0.115 | 0.92 | 0.77 | 1.11 | 0.388 |

| Region: Unknown Central (reference = Northeast) | 1.23 | 0.91 | 1.67 | 0.173 | 0.31 | 0.04 | 2.62 | 0.281 |

| Region: West Central (reference = Northeast) | 1.04 | 0.95 | 1.13 | 0.444 | 0.99 | 0.79 | 1.23 | 0.921 |

| Plan type: HMO (reference = FFS) | 0.80 | 0.72 | 0.90 | 0.000 | 0.83 | 0.62 | 1.12 | 0.219 |

| Plan type: Other (reference = FFS) | 1.08 | 0.94 | 1.25 | 0.274 | 0.99 | 0.60 | 1.63 | 0.968 |

| Plan type: POS (reference = FFS) | 1.01 | 0.89 | 1.16 | 0.833 | 1.07 | 0.78 | 1.46 | 0.683 |

| Plan type: PPO (reference = FFS) | 1.02 | 0.96 | 1.08 | 0.607 | 1.11 | 0.95 | 1.29 | 0.183 |

| Rural residence (reference = urban or unknown) | 1.03 | 0.95 | 1.12 | 0.474 | 1.10 | 0.90 | 1.36 | 0.346 |

| Median household income | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.162 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.990 |

| Non-melanoma cancer | 0.97 | 0.89 | 1.06 | 0.529 | 1.08 | 0.87 | 1.34 | 0.495 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.98 | 0.93 | 1.04 | 0.570 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 1.12 | 0.772 |

| Retinal vein occlusion | 0.95 | 0.78 | 1.14 | 0.552 | 1.01 | 0.68 | 1.50 | 0.963 |

| Diabetic macular edema | 0.91 | 0.80 | 1.04 | 0.152 | 1.06 | 0.77 | 1.45 | 0.728 |

| Cataracts | 1.03 | 0.96 | 1.10 | 0.447 | 1.08 | 0.91 | 1.30 | 0.381 |

| Glaucoma | 0.97 | 0.91 | 1.04 | 0.385 | 1.05 | 0.91 | 1.23 | 0.488 |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 1.00 | 0.92 | 1.09 | 0.953 | 0.82 | 0.66 | 1.00 | 0.055 |

| Glucocorticoids | 1.14 | 1.05 | 1.24 | 0.002 | 1.18 | 0.96 | 1.46 | 0.121 |

| Photodynamic therapy | 0.90 | 0.60 | 1.36 | 0.616 | 0.82 | 0.30 | 2.29 | 0.710 |

| Laser photocoagulation therapy | 0.87 | 0.57 | 1.32 | 0.500 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 3.69 | 0.267 |

| Cataract surgery | 1.02 | 0.93 | 1.13 | 0.630 | 1.18 | 0.93 | 1.50 | 0.172 |

| Intravitreal steroid injection | 0.92 | 0.85 | 0.98 | 0.015 | 1.06 | 0.87 | 1.29 | 0.587 |

| Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 0.680 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 1.04 | 0.795 |

| Unique 3-digit ICD-9-CM diagnoses | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.460 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.642 |

| Unique National Drug Codes | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.343 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.349 |

| Total healthcare expenditures | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.586 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.379 |

CI confidence interval, FFS fee-for-service, HMO health maintenance organization, ICD-9-CM International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical modification, POS point-of-service, PPO preferred provider organization

aScale = 2.568 for 6 month analyses; 1.530 for 12 month analyses

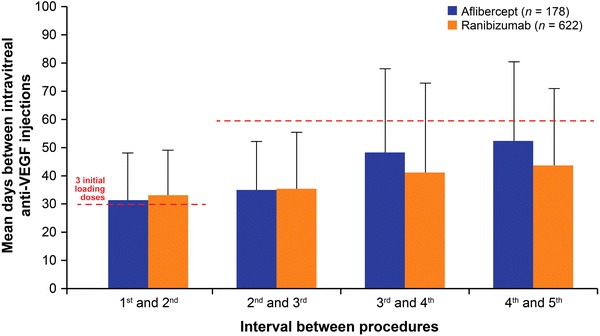

Figure 3 displays the distribution of days between each intravitreal anti-VEGF injection over time, calculated among all study-eligible patients regardless of having any minimum duration of available follow-up, as described in the methods above. The overall mean days between each injection, weighted per number of patients receiving each subsequent injection, were 42.4 for aflibercept patients and 40.6 for ranibizumab patients, a difference of 1.8 (95% CI 1.3–2.3) days. Appendix Figure 1 displays a sensitivity analysis in which the distribution of days between each of the first five intravitreal anti-VEGF injections was calculated among patients with at least five injections. In this sensitivity analysis, the overall mean days between each of the first five injections were 42.0 for aflibercept patients and 38.4 for ranibizumab patients, a difference of 3.6 days (95% CI 2.1–4.9).

Fig. 3.

Mean days between each intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) injection over time. *The overall mean days between each injection, weighted per number of patients receiving each subsequent injection, were 42.4 for aflibercept patients and 40.6 for ranibizumab patients, a difference of 1.8 days (95% CI 1.3–2.3). Red dashed lines drawn at 30 and 60 days represent the expected time between aflibercept injections based on package insert: once-monthly for the first 3 months followed by once every other month for aflibercept. Error bars represent one standard deviation. To increase sample size, this analysis was conducted among all study-eligible patients regardless of having any minimum duration of available follow-up. The number of contributing patients for calculations were—1 to 2: Aflibercept (A) = 570, Ranibizumab (R) = 1 502; 2–3: A = 418, R = 1 173; 3–4: A = 270, R = 859; 4–5: A = 178, R = 622; 5–6: A = 95, R = 455; 6–7: A = 57, R = 319; 7–8: A = 33, R = 234; 8–9: A = 20, R = 161; 9–10: A = 15, R = 116; 10 +: A = 7, R = 75

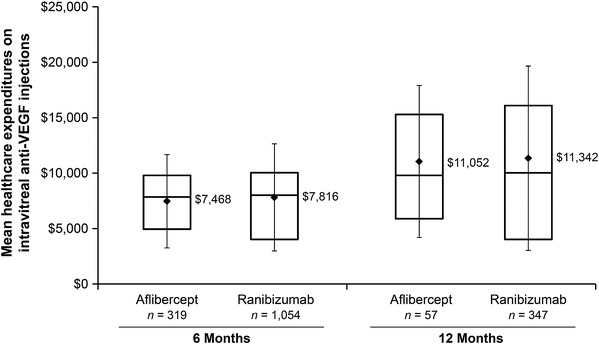

Figure 4 displays the unadjusted healthcare expenditures on intravitreal anti-VEGF injections over the first 6 months and 12 months after the index date. In the 6 month analyses, the mean expenditure on injections was $7,468 in the aflibercept patients and $7,816 in the ranibizumab patients. Multivariable regression determined that the expenditures on injections did not differ in a statistically significant manner between aflibercept patients and ranibizumab patients (Table 4: Cost Ratio [CR] treating ranibizumab as reference category = 0.96, 95% CI 0.89–1.04, P = 0.338). Consistent with the models examining the number of intravitreal anti-VEGF injections, factors that were significantly associated with lower healthcare expenditures on intravitreal anti-VEGF injections included being a member of a Health Maintenance Organization (vs. fee-for-service) (IRR = 0.79, 95% CI 0.69–0.90, P = 0.001) and having baseline treatment with intravitreal steroid injection (IRR = 0.91, 95% CI 0.83–1.00, P = 0.039). The only factor that was significantly associated with greater expenditures on intravitreal anti-VEGF injections was having baseline treatment with non-intravitreal glucocorticoids (IRR = 1.17, 95% CI 1.05–1.30, P = 0.005).

Fig. 4.

Healthcare expenditures on intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) injections over the first 6 months (left bars) and 12 months (right bars) after the index date. *The boxes represent the 25th percentile (bottom of box), median (line in center of box), and 75th percentile (top of box); the diamonds are means with error bars representing the standard deviation

Table 4.

Multivariable generalized linear model of healthcare expenditures on intravitreal anti-VEGF injections over the first 6 and 12 months after the index date

| Parameter | 6 Month analyses | 12 Month analyses | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost Ratio | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P | Cost Ratio | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P | |

| Aflibercept (reference = ranibizumab) | 0.96 | 0.89 | 1.04 | 0.338 | 0.92 | 0.74 | 1.13 | 0.429 |

| Age 18–64 years (reference = 85 + years) | 1.03 | 0.90 | 1.17 | 0.684 | 0.89 | 0.66 | 1.20 | 0.457 |

| Age 65–74 years (reference = 85 + years) | 1.02 | 0.92 | 1.13 | 0.696 | 0.96 | 0.76 | 1.20 | 0.697 |

| Age 75–84 years (reference = 85 + years) | 1.04 | 0.97 | 1.12 | 0.276 | 0.95 | 0.80 | 1.13 | 0.583 |

| Male (reference = female) | 0.98 | 0.91 | 1.04 | 0.461 | 0.94 | 0.81 | 1.09 | 0.405 |

| Region: North Central (reference = Northeast) | 0.98 | 0.89 | 1.07 | 0.607 | 0.94 | 0.76 | 1.15 | 0.539 |

| Region: South (reference = Northeast) | 1.04 | 0.95 | 1.14 | 0.384 | 0.92 | 0.74 | 1.13 | 0.412 |

| Region: Unknown Central (reference = Northeast) | 0.90 | 0.61 | 1.32 | 0.578 | 0.29 | 0.07 | 1.25 | 0.098 |

| Region: West Central (reference = Northeast) | 0.99 | 0.88 | 1.12 | 0.885 | 0.93 | 0.71 | 1.21 | 0.593 |

| Plan type: HMO (reference = FFS) | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.90 | 0.001 | 0.81 | 0.59 | 1.11 | 0.196 |

| Plan type: Other (reference = FFS) | 1.11 | 0.93 | 1.34 | 0.243 | 1.05 | 0.58 | 1.92 | 0.867 |

| Plan type: POS (reference = FFS) | 0.95 | 0.81 | 1.12 | 0.526 | 1.05 | 0.73 | 1.49 | 0.805 |

| Plan type: PPO (reference = FFS) | 0.96 | 0.89 | 1.04 | 0.320 | 1.02 | 0.85 | 1.22 | 0.821 |

| Rural residence (reference = urban or unknown) | 1.01 | 0.91 | 1.11 | 0.919 | 1.14 | 0.90 | 1.45 | 0.273 |

| Median household income | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.615 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.353 |

| Non-melanoma cancer | 1.00 | 0.89 | 1.12 | 0.971 | 1.24 | 0.95 | 1.62 | 0.107 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.99 | 0.92 | 1.06 | 0.734 | 0.95 | 0.82 | 1.12 | 0.558 |

| Retinal vein occlusion | 0.95 | 0.76 | 1.20 | 0.679 | 0.97 | 0.62 | 1.52 | 0.901 |

| Diabetic macular edema | 0.94 | 0.81 | 1.11 | 0.471 | 1.13 | 0.78 | 1.65 | 0.516 |

| Cataracts | 1.01 | 0.93 | 1.10 | 0.830 | 1.13 | 0.91 | 1.39 | 0.271 |

| Glaucoma | 0.98 | 0.90 | 1.06 | 0.631 | 1.09 | 0.91 | 1.30 | 0.340 |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 1.04 | 0.94 | 1.16 | 0.451 | 0.88 | 0.70 | 1.11 | 0.296 |

| Glucocorticoids | 1.17 | 1.05 | 1.30 | 0.005 | 1.15 | 0.88 | 1.50 | 0.321 |

| Photodynamic therapy | 0.76 | 0.45 | 1.28 | 0.301 | 0.67 | 0.24 | 1.90 | 0.455 |

| Laser photocoagulation therapy | 0.83 | 0.52 | 1.32 | 0.428 | 0.37 | 0.09 | 1.56 | 0.175 |

| Cataract surgery | 1.02 | 0.90 | 1.15 | 0.772 | 1.05 | 0.78 | 1.40 | 0.765 |

| Intravitreal steroid injection | 0.91 | 0.83 | 1.00 | 0.039 | 1.00 | 0.79 | 1.27 | 0.983 |

| Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.02 | 0.863 | 0.97 | 0.91 | 1.03 | 0.252 |

| Unique 3-digit ICD-9-CM diagnoses | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.334 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 0.331 |

| Unique National Drug Codes | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.082 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 0.442 |

| Total healthcare expenditures | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.260 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.716 |

CI confidence interval, FFS fee-for-service, HMO health maintenance organization, ICD-9-CM International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical modification, POS point-of-service, PPO preferred provider organization

In the 12 month analyses, the mean expenditure on injections was $11,052 in the aflibercept patients and $11,342 in the ranibizumab patients. Again, expenditures on injections did not differ in a statistically significant manner between aflibercept patients and ranibizumab patients (Table 4: CR treating ranibizumab as reference category = 0.92, 95% CI 0.74–1.13, P = 0.4291).

In sensitivity analyses including patients in the 12 month analyses who had initiated ranibizumab prior to the aflibercept approval date of November 18, 2011 (N = 8,519), study findings were generally similar to the primary analyses—with the mean number of injections and mean healthcare expenditures on injections being slightly lower (5.3 [versus 5.8 in the primary analyses] and $11,105 [versus $11,342 in the primary analyses], respectively; data not shown in tables).

Discussion

This retrospective analysis examined first-line intravitreal anti-VEGF treatment patterns in wet AMD. Comparing between patients who were treated with aflibercept or ranibizumab, the two newest and most commonly used FDA-approved therapies for wet AMD, we found that the number of intravitreal anti-VEGF injections and healthcare expenditures on intravitreal anti-VEGF injections did not differ in a statistically significant manner. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine these outcomes in the ‘real world’ setting of routine clinical practice. Thus, our findings are a new and unique contribution to the literature.

Ranibizumab was consistently administered by intravitreal injection once every 40.6 days, on average. Aflibercept was administered in a similar manner (once every 42.4 days, on average) and more frequently than would be expected per recommendations in the prescribing information. The mean days between injections of aflibercept never reached a level of once every other month. As noted, ranibizumab’s prescribing information indicates that it may be administered with less frequent dosing with regular assessment after the first three monthly doses, while aflibercept’s prescribing information indicates that it may be administered as frequently as once per month, though clinical evidence does not support this dosing option being more efficacious than the recommended dosing option. Ultimately, the ‘real world’ frequency of intravitreal anti-VEGF injections is governed by physicians’ judgments regarding patients’ needs, preferences, and other factors. Future research to elucidate the factors driving these treatment patterns is warranted and could be conducted through physician surveys.

This study was subject to limitations. First, as described in Appendix A, aflibercept and ranibizumab came to market before receiving their own specific HCPCS codes to which physicians could bill. Consequently, for some of the times covered within our overall study period of January 1, 2006 to April 30, 2013, we had to rely on previously published algorithms that use payment information recorded on administrative claims coded with non-specific HCPCS codes that co-occur with administrative claims coded with intravitreal injection CPT codes. Such algorithms could result in misclassification of study patients. Second, although administrative claims data form the basis of a vast body of published epidemiologic and health economic literature, they are not collected specifically for research purposes, but instead for the purpose of healthcare reimbursement. Administrative claims data can be subject to coding error, which can result in measurement error for the variables that rely on such codes. Third, although the MarketScan Commercial and Medicare databases represent the largest proprietary non-probability sample in administrative claims databases, they are not necessarily representative of all individuals in the United States, including individuals who are uninsured or insured through other means such as self-pay or the Medicaid program. Finally, further follow-up of this subject is warranted given the relatively short period of time for which aflibercept had been on the market for this initial evaluation.

Conclusion

Despite differences in the prescribing information recommendations for the frequency of dosing between aflibercept and ranibizumab, these two anti-VEGF agents were used with nearly equal frequency and intervals between injections, resulting in similar intravitreal anti-VEGF injection healthcare expenditures among wet AMD patients initiating first-line intravitreal anti-VEGF treatment. Although further follow-up is warranted, this initial evaluation of aflibercept usage compared to ranibizumab indicates similar treatment patterns and durability in a real-world setting.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Stephen Johnston, Kathleen Wilson, Alice Huang, David Smith, Helen Varker, and Adam Turpcu all made the following contributions: (1) substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; and (3) final approval of the version to be published. The authors wish to acknowledge Diana Stetsovsky for assistance with statistical programming. Sponsorship and article processing charges for this study was funded by Genetech Inc. Stephen S. Johnston is the guarantor for this article and takes full responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Conflict of interest

Stephen Johnston is an employee of Truven Health Analytics. Kathleen Wilson is an employee of Truven Health Analytics. Alice Huang is an employee of Truven Health Analytics. David Smith is an employee of Truven Health Analytics. Helen Varker is an employee of Truven Health Analytics. Adam Turpcu is an employee of Genentech, Inc. Truven Health Analytics was paid by Genentech, Inc. to conduct this study.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. The data contained in the databases Truven Health MarketScan ® Commercial Claims and Encounters (Commercial) and Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits (Medicare Supplemental) are statistically de-identified and have been certified to satisfy the conditions set forth in Sections 164.514 (a)-(b)1ii of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. As such, Institutional Review Board approval and written informed consent were not sought for this study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- 1.Leibowitz HM, Krueger DE, Maunder LR, et al. The Framingham Eye Study Monograph. VI. Macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 1980;24(suppl):428–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein R, Chou CF, Klein BE, Zhang X, Meuer SM, Saaddine JB. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the US population. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(1):75–80. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein R, Klein BE, Linton KL. Prevalence of age-related maculopathy. The Beaver Dam Study. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:933–943. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(92)31871-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Academy of Ophthalmology. age-related macular degeneration preferred practice pattern - updated October 2011. http://one.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/agerelated-macular-degeneration-ppp-september-200. Accessed 14 Sept 2013.

- 5.Ferris FL, III, Fine SL, Hyman LA. Age-related macular degeneration and blindness due to neovascular maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:1640–1642. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040031330019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macugen [package insert]. San Dimas, CA: Gilead Sciences, Inc; 2011.

- 7.Lucentis [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech, Inc.; 2013.

- 8.Eylea [package insert]. Tarrytown, NY: Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2013.

- 9.Busbee BG, Ho AC, Brown DM, Heier JS, Suñer IJ, Li Z, Rubio RG, Lai P; HARBOR Study Group. Twelve-month efficacy and safety of 0.5 mg or 2.0 mg ranibizumab in patients with subfoveal neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(5):1046–56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.National Center for Health Statistics. The International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm.

- 11.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.